Abstract

Two disorders of attachment have been consistently identified in some young children following severe deprivation in early life: reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder. However, less is known about whether signs of these disorders persist into adolescence. We examined signs of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder at age 12 years in 111 children who were abandoned at or shortly after birth and subsequently randomized to care as usual or to high-quality foster care, as well as in 50 comparison children who were never institutionalized. Consistent with expectations, those who experienced institutional care in early life had more signs of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder at age 12 years than children never institutionalized. Additionally, using a conservative intent-to-treat approach, those children randomized to foster care had significantly fewer signs of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder than those randomized to care as usual. Analyses within the ever institutionalized group revealed no effects of the age of placement into foster care, but number of caregiving disruptions experienced and the percentage of the child’s life spent in institutional care were significant predictors of signs of attachment disorders assessed in early adolescence. These findings indicate that adverse caregiving environments in early life have enduring effects on signs of attachment disorders, and provide further evidence that high-quality caregiving interventions are associated with reductions in both reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder.

It has been known that serious social deprivation is associated with attachment disorders for decades. Dating back to the mid-20th century, descriptive, cross-sectional studies demonstrated that children raised in institutions exhibited unusual social behaviors, including social inhibition and unresponsiveness and social disinhibition and boundary violations (Goldfarb, 1945; Levy, 1947; Provence & Lipton, 1962; Tizard & Rees, 1975; Wolkind, 1974). These unusual behaviors are what we now define as reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder (Zeanah & Gleason, 2015; Zeanah & Smyke, 2015). More recently, several groups have reported that young children living in institutions have similar signs of disturbances in their attachment and social behaviors (Dobrova-Krol, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Van Ijzendoorn, & Juffer, 2010; Smyke, Dumitrescu, & Zeanah, 2002; Zeanah, Smyke, Koga, & Carlson, 2005).

Attachment disorders first were defined in formal nosologies in the 3rd edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [(DSM-III) (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1980)]. The criteria were later revised in DSM-III-R (APA, 1987) and again in DSM-IV (APA, 1994). Still, for almost 20 years, the disorder attracted little attention from investigators, so these revisions to the criteria occurred without any systematic research. Volkmar (1997) indicated that despite the absence of relevant studies, the disorder was maintained in DSM-IV, primarily because it appeared to encompass a unique set of signs and symptoms that were not explained by other disorders.

More recent research has led to a broad consensus about how attachment disorders are defined in young children (Rutter, Kreppner, & Sonuga-Barke, 2009; Zeanah & Gleason, 2015). Two clinical patterns, an emotionally withdrawn/inhibited pattern (i.e., reactive attachment disorder) and an indiscriminately social pattern (i.e., disinhibited social engagement disorder) have been described. Studies using both continuous (O’Connor, Marvin, Rutter, Olrick, & Britner, 2003; Pears, Bruce, Fisher, & Kim, 2010; Smyke et al., 2002; Zeanah et al., 2005) and categorical measures of these disorders (Boris et al., 2004; Zeanah et al., 2004) have affirmed that reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder can be reliably identified in a minority of maltreated, institutionalized, and formerly institutionalized children. Research on post-institutionalized, inter-country adoptees has focused primarily on children’s disinhibited social behavior, sometimes termed “indiscriminate friendliness” (Bruce, Tarullo, & Gunnar, 2009; Chisholm, 1998; O’Connor & Rutter, 2000; Olsavsky et al., 2013; Van Den Dries, Juffer, Van Ijzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Alink, 2012), but assessments of children reared in institutions and maltreated children in foster care have included identification of both reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder (Boris et al., 2004; Jonkman et al., 2014; Lehmann, Breivik, Heiervang, Havik, & Havik, 2015; Oosterman & Schuengel, 2007; Pears et al., 2010; Smyke et al., 2002; Soares et al., 2014; Zeanah et al., 2004, 2005).

There is also a consensus that these disorders arise when the child’s first attachment relationships are still forming and are compromised by early social neglect (reviewed in Zeanah & Gleason, 2015), suggesting there may be a sensitive period for the onset of such disorders. A number of studies have demonstrated that lack of appropriate caregiving is associated with attachment disorders (Boris et al., 2004; Bruce et al., 2009; Chisholm, 1998; Gleason et al., 2011; O’Connor & Rutter, 2000; Oosterman & Schuengel, 2007; Pears et al., 2010; Smyke et al., 2002; Van Den Dries et al., 2012; Zeanah et al., 2005, 2004), leading to the requirement in DSM-5 (APA, 2013) that “insufficient caregiving” be included as a criterion for both reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder.

Indiscriminate social behavior is one of the most persistent social abnormalities in children adopted from institutions, often remaining evident even after children have formed attachments to their adoptive parents, where inhibited social behavior disappears with the development of attachment relationships (Rutter et al., 2010, 2009; Zeanah & Gleason, 2015; Zeanah, 2000). Further, unlike with reactive attachment disorder, individual differences in adoptees’ new family environments do not seem to be associated with degree of recovery from signs of disinhibited social engagement disorder (Rutter et al., 2010).

Because institutional rearing has been repeatedly associated with signs of attachment disorders in young children, one question is whether risks persist beyond early childhood even for children who have experienced subsequent care in families. Two previous longitudinal studies have demonstrated persistence of signs of disinhibited social engagement disorder into adolescence (Hodges & Tizard, 1989; Rutter et al., 2010), but no studies have previously examined persistence of reactive attachment disorder, as defined by DSM-5, beyond early childhood. Thus, one aim of the current investigation is to determine if children with histories of deprivation in the form of early institutional rearing have persistent elevations in signs of both inhibited and disinhibited social behavior at age 12 years.

The most systematic intervention study to date designed to remediate attachment disorders is the Bucharest Early Intervention Project, a randomized controlled trial of foster care as an alternative to institutional care among children with histories of severe, early deprivation (Zeanah et al., 2003). In this study, 136 children abandoned at or near birth and cared for in institutions for young children in Bucharest, were assessed at baseline for signs of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder through structured interviews with their caregivers. There were significantly more signs of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder among children residing in institutions compared to children living with their families who had no history of institutional rearing (Zeanah et al., 2005). Among children in institutional care, following the baseline assessment all were randomly assigned to either care as usual or to removal from institutions and placement in foster care created for the project (see Nelson, Fox, & Zeanah, 2014; Smyke, Zeanah, Fox, & Nelson, 2009). At each assessment during the RCT – age 30, 42 and 54 months – the children in foster care had fewer signs of reactive attachment disorder than children in care as usual (Smyke et al., 2012). We found that at 42 and 54 months, children in foster care had fewer signs of disinhibited social engagement disorder than children in care as usual. The RCT ended when the children were 54 months of age, and the BEIP foster care network was turned over to the local governmental authorities. A follow-up four years later, when children were 8 years old, demonstrated that children originally assigned to BEIP foster care continued to show fewer signs of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder than children originally assigned to care as usual (Smyke et al., 2012). The second aim of the current follow-up investigation was to determine if the original intervention groups, using a conservative “intent-to-treat” approach, showed differences in signs of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder more than 10 years after the children were randomized, when children were 12 years old.

In addition to examining participants based on presence or absence of any institutional care history (ever institutionalized group; never institutionalized group) and the intent-to-treat groups among the ever institutionalized group (care as usual group; foster care group), we also sought to explore whether age of placement within the foster care group was associated with signs of attachment disorders at age 12 years. Among all ever institutionalized children, we examined whether number of placements and percent time spent in institutional care were associated with signs of attachment disorders at age 12 years. In previous assessments, earlier foster placement was associated with reduced signs of disinhibited social engagement disorder (Smyke et al., 2012). There was, however, no relation between age of placement in BEIP foster care and signs of reactive attachment disorder, presumably because there were no elevations in signs of reactive attachment disorder at any assessment age after placement for children in the foster care group.

One of the principles of BEIP was that children’s participation in the study would not affect placement decisions, which were made exclusively by the local child protection authorities. Over time, some children were adopted, others were returned to their biological parents, and others were placed in government foster care that had not existed when the study began. As time passed, some of the children’s caregivers died or were no longer able to adequately care for them. A few children developed serious behavioral challenges that led to their placement in group care. Thus, an important question was whether the number of caregiving disruptions affected attachment disorder outcomes years later. In fact, an assessment of psychopathology at 12 years of age in this sample demonstrated that those children who had remained with their original BEIP foster parents had significantly fewer signs of internalizing and externalizing disorders than those who had experienced one or more placement disruptions (Humphreys et al., 2015). Thus, we examined the total number of placement disruptions for all ever institutionalized children, as well as the percentage of time that children spent in any institutional care, in order to assess how variation in these markers of child’s caregiving history may related to signs of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder. We predicted that any history of institutional care, placement into the study-sponsored foster care, fewer caregiving disruptions, and less time in institutional care would be associated with reduced signs of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder at age 12 years.

Method

Participants

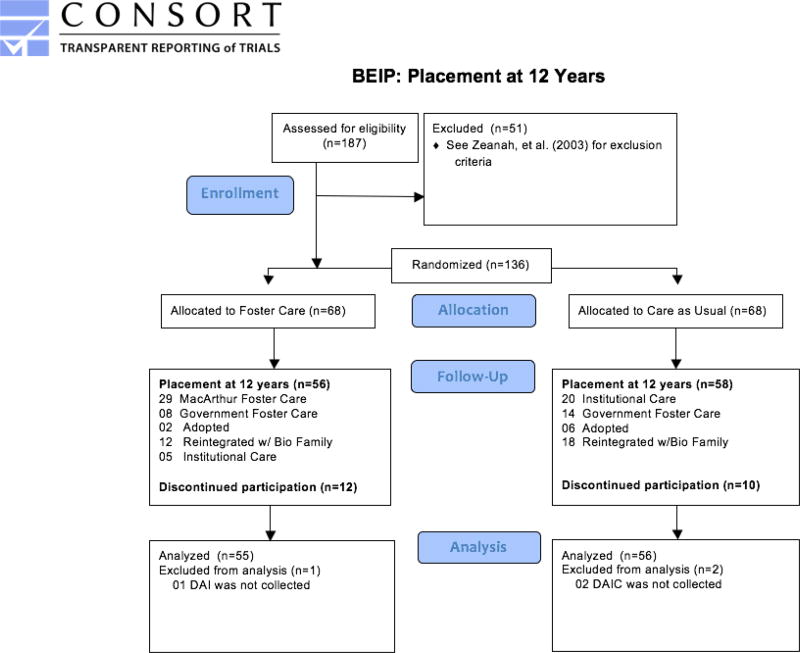

The participants in this investigation were 161 children who were assessed at a mean age of 12.79 years (SD=0.63) as part of the longitudinal BEIP investigation (Zeanah et al., 2003). Of the original 136 children, 111 were included in this follow-up (82%) (Figure 1). Details about the original sample are available elsewhere (Nelson et al., 2014). The remaining 50 children (21 boys and 29 girls) were a never institutionalized Romanian children recruited from pediatric clinics or schools in Bucharest who were included as a typically developing comparison group of Romanian children.

Figure 1.

Group Status in Early Adolescence for Children Living in Romanian Institutions Who Were Assigned to Usual Care or Foster Care (CONSORT)

Following approvals by the institutional review boards of the three principal investigators (CHZ, NAF, CAN), and by the local Commissions on Child Protection in Bucharest, the study commenced in collaboration with the Institute of Maternal and Child Health of the Romanian Ministry of Health. A data safety monitoring board in Bucharest reviewed the assessments for the current follow-up. Consent was obtained and signed for by each child’s legal guardian as per Romanian law. Assent for each procedure was obtained from the children. We and others have previously written about the ethical dimensions of the study (Miller, 2009; Millum & Emanuel, 2007; Zeanah et al., 2006; Zeanah, Fox, & Nelson, 2012).

Procedure

Following baseline assessment, children were randomly assigned to the care as usual group or foster care group by drawing names from a hat. The children in the two groups were comparable on age, gender, ethnicity, birth weight, developmental quotient, observed caregiving environment, caregiver ratings of behavior problems, and competence at baseline (Smyke et al., 2007). Because all decisions about placement were made by Romanian child protection authorities, and because over time policies about the care of institutionalized children changed, in the years following randomization, some children were adopted within Romania, some were returned to the parents who had abandoned them, some were placed in government foster care, and some were later readmitted to institutions because of serious behavior problems (see Figure 1).

The intent-to-treat groups comprised 56 children in the care as usual group and 55 children in the foster care group; there were also 50 non-randomized comparison children in the never institutionalized group (Table 1). As the randomization occurred at mean age 22 months, we expected that intervening events might contribute to outcomes at age 12 years. This was particularly relevant given placement changes in the foster care group have been linked to differences in IQ (Fox, Almas, Degnan, Nelson, & Zeanah, 2011) and psychopathology (Humphreys et al., 2015).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics by group

| Gender | Age | Romanian Ethnicity |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Girls (N=83) |

Boys (N=78) |

Mean | SD | N | % |

| Care as usual group (N=56) | 27 | 29 | 12.86 | 0.78 | 25 | 45 |

| Foster care group (N=55) | 27 | 28 | 12.74 | 0.62 | 32 | 58 |

| Never institutionalized group (N=50) | 29 | 21 | 12.79 | 0.63 | 45 | 92 |

Measures

Disturbances of Attachment Interview, Early Adolescent

This measure is a structured interview of caregivers about signs of disordered attachment that has been extensively used and validated at younger ages (Gleason et al., 2011; Smyke et al., 2012; Zeanah et al., 2005). The Disturbances of Attachment Interview was translated into Romanian, back-translated into English, and assessed for meaning at each step by bilingual research staff. For children living with biological parents or foster parents, the mother reported on the child’s behavior. For children living in institutions, an institutional caregiver who worked with the child regularly and knew the child well reported on the child’s behavior. Caregivers were asked a series of questions about their child’s attachment behavior, and response options for each item were 0, 1, or 2. The inhibited social behavior scale comprised 7 items (see appendix for Disturbances of Attachment Interview items). The answers provided from the two items related to seeking comfort from caregivers [3A and 3B] were averaged, and given the analytic technique for handling the non-normal distribution of the data required that all values be integers, the scale was multiplied by 2. Thus, the range for possible scores on the inhibited social behavior scale was 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating higher levels of inhibited social behavior. The disinhibited social behavior scale comprised 5 items. The range for possible scores on the disinhibited social behavior scale was 0 to 10. The coefficient alpha for both scales were very good (Cronbach’s α = .88 and .82, for reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder signs, respectively), indicating high internal consistency. Furthermore, evidence supporting the use of the Disturbances of Attachment Interview at age 12 years comes from positive correlations between the reactive attachment disorder signs and previously published signs measured at age 54 months (r(128) = .52, p < .001) and 8 years (r(156) = .61, p < .001). Similar correlations were found with the association between disinhibited social engagement disorder signs at this follow-up and signs measured at age 54 months (r(127) = .46, p < .001) and 8 years (r(156) = .55, p < .001).

Intervention

Because foster care was extremely limited in Bucharest at the outset of the study, the investigators, with Romanian collaborators, created a foster care network (Smyke et al., 2009; Zeanah et al., 2003). The foster parents were supported by social workers in Bucharest who received regular consultation from U.S. clinicians. After recruiting and subsequent screening, 56 foster families were selected to care for 68 children. Described more fully elsewhere (Nelson et al., 2014; Smyke et al., 2012, 2009), the foster care intervention was designed to be affordable, replicable, and grounded in findings from developmental research on enhancing caregiving quality. Parents were explicitly encouraged to form attachments to the children in their care and to make long term commitments to them.

Statistical Analysis

Scores estimates were obtained for each group, along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of group differences, using generalized linear models. Generalized linear models provide an alternative to the general linear model that allows for the outcome measures to have non-normal distributions. We specified a negative binomial distribution to examine predictors of scores from the Disturbances of Attachment Interview in order to model data with non-normal distributions (e.g., count data). For each analysis, a Wald χ2 was obtained to examine the effect of group (e.g., ever institutionalized group vs. never institutionalized group) or dimensional caregiving measure (e.g., percent time spent in institutional care). Means are presented using 95% CI for each attachment disorder domain by group. Participant ethnicity and sex were included as covariates in all analyses.

Results

Disturbances of Attachment Interview Scores by History of Institutional Care

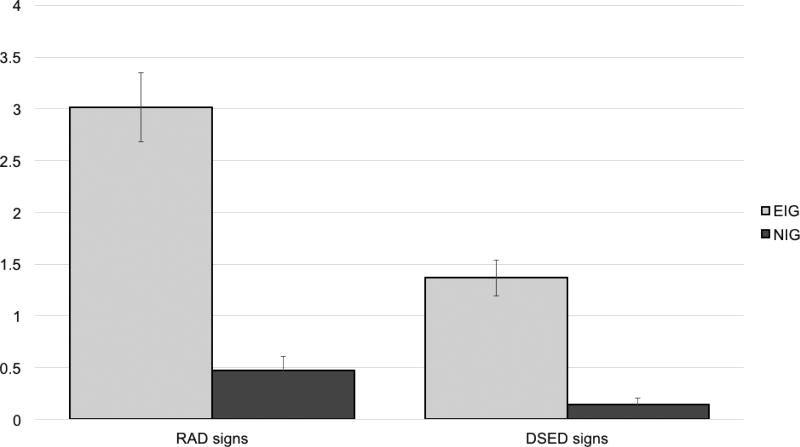

We examined scores from the inhibited and disinhibited social behavior scales from the Disturbances of Attachment Interview measured at age 12 years, comparing the ever institutionalized group and never institutionalized group (see Figure 2). There was a significant effect of group on inhibited social behavior (Wald χ2=34.24, df=1, p<.001). The ever institutionalized group (M=3.01, SE=0.33; 95% CI [2.43, 3.74]) had significantly higher scores than the never institutionalized group (M=0.47, SE=0.14; 95% CI [0.27, 0.84]). However, this main effect was qualified by a group by sex interaction (Wald χ2=4.16, df=1, p=.04). Among both girls and boys, there was a significant effect of group on inhibited social behavior (Wald χ2=17.97, df=1, p<.001 and Wald χ2=13.58, df=1, p<.001, respectively). However, the ever institutionalized males (M=3.32, SE=0.51; 95% CI [2.46, 4.50]) had higher levels of inhibited social behavior than all other groups (ps < .038); ever institutionalized females (M=2.74, SE=0.44; 95% CI [2.00, 3.76]), never institutionalized males (M=0.90, SE=0.33; 95% CI [0.44, 1.84]), and never institutionalized females (M=0.18, SE=0.10; 95% CI [0.06, 0.53]).

Figure 2.

Disturbances of Attachment Interview scores by group for signs for reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder. Note. RAD=reactive attachment disorder. DSED=disinhibited social engagement disorder. EIG=ever institutionalized group. NIG=never institutionalized group. Error bars represent the standard error.

There was an effect of group on disinhibited social behavior (Wald χ2=23.62, df=1, p<.001). The ever institutionalized group (M=1.37, SE=0.17; 95% CI [1.07, 1.75]) had significantly higher scores than the never institutionalized group (M=0.14, SE=0.06; 95% CI [0.06, 0.34]). The possibility for a group × sex interaction was examined; however the model was unable to compute an estimate because all never institutionalized females had scores of 0. The analysis was re-conducted within boys only, and there was a significant effect of group on inhibited social behavior (Wald χ2=8.53, df=1, p=.003). Estimated averages were calculated for group differences within girls (95% CI [0.82, 1.74]) and boys (95% CI [0.55, 1.71]) separately, which both indicated significant group differences.

Disturbances of Attachment Interview Scores by Intent-to-Treat Groupings

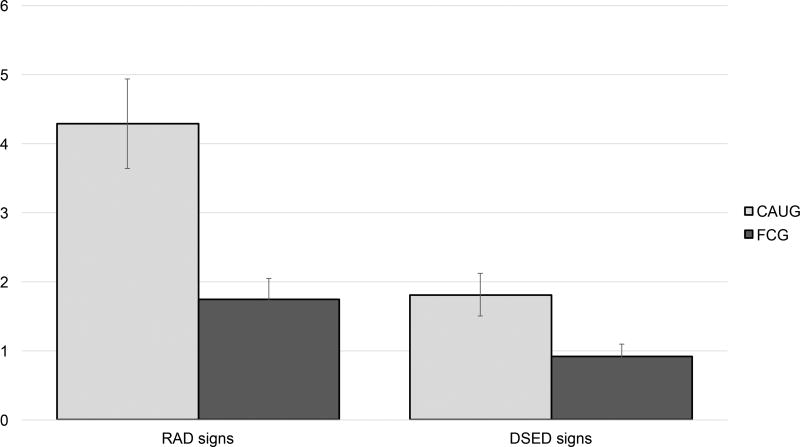

We examined Disturbances of Attachment Interview scores for the inhibited and disinhibited social behavior scales by the intent-to-treat groupings (care as usual group vs. foster care group; see Figure 3). There was a significant effect of group on inhibited social behavior (Wald χ2=14.62, df=1, p<.001). The care as usual group (M=4.28, SE=0.65; 95% CI [3.18, 5.77]) had significantly higher scores than the foster care group (M=1.75, SE=0.30; 95% CI [1.11, 3.96]). The group × sex interaction was not significant (Wald χ2=1.06, df=1, p=.30).

Figure 3.

Disturbances of Attachment Interview scores by group for signs for reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder. Note. RAD=reactive attachment disorder. DSED=disinhibited social engagement disorder. CAUG=care as usual. FCG=foster care group. Error bars represent the standard error.

There was also an effect of group on disinhibited social behavior (Wald χ2=6.73, df=1, p=.091). The care as usual group (M=1.81, SE=0.30; 95% CI [1.30, 2.52]) had significantly higher scores than the foster care group (M=0.92, SE=0.18; 95% CI [0.63, 1.36]). Again, the group × sex interaction was not significant (Wald χ2=0.43, df=1, p=.51).

Age of Placement

Among those children randomized to the foster care group, we examined whether age of placement into the MacArthur foster care was associated with signs of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder. For age of placement, we grouped individuals based on whether the placement occurred before or after age 24 months, given that this age may be represent a sensitive period for some developmental outcomes and prior work linking age of placement to attachment outcomes. The effect of placement by age 24 months on inhibited social behavior was not statistically significant (Wald χ2=3.40, df=1, p=.065). Those placed after age 24 months (M=2.33, SE=0.58; 95% CI [1.13, 3.78]) had marginally higher scores than those placed prior to age 24 months (M=1.07, SE=0.33; 95% CI [0.58, 1.95]). There was no association between age of placement and disinhibited social behavior (Wald χ2=1.68, df=1, p=.20).

Number of Placement Disruptions and Percent Time in Institutional Care

Two other variables related to institutional care exposure and placement disruptions were examined within the ever institutionalized group: (1) the number of placement disruptions experienced by children up to the age 12 assessment; and (2) percent time spent in institutional care at the age 12 assessment. The total number of placement disruptions experienced from birth to age 12 was significantly positively correlated with inhibited social behavior (Wald χ2=7.61, df=1, B=0.19, SE=0.07, p=.006), but was not related to disinhibited social behavior (Wald χ2=0.59, df=1, B=0.06, SE=0.08, p=.44). For the percent time spent in institutional care, there was a significant positive association between time spent institutionalized and inhibited social behavior (Wald χ2=26.29, df=1, B=0.02, SE=0.004, p<.001). A similar association was found between percent time spent in institutional care and disinhibited social behavior (Wald χ2=13.98, df=1, B=0.02, SE=0.004, p<.001).

As a follow-up analysis, in order to attempt to determine the role of early vs. later institutional care exposure on signs of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder, we re-computed the above analyses on percent time in institutional care at age 12, but added the covariate of percent time in institutional care at age 54 months, when the intervention trial was complete. This approach allows us to determine whether, after accounting for the degree of institutional care exposure in early life, institutional care in the subsequent years incrementally predicted signs of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder. These analyses revealed that, even after controlling for percent time in institutional care at age 54 months, percent time in institutional care at 12 years significantly positively predicted signs of both reactive attachment disorder (Wald χ2=6.76, B=0.02, SE=0.01, p=.009) and disinhibited social engagement disorder (Wald χ2=4.46, B=0.02, SE=0.01, p=.035).

Discussion

We assessed signs of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder in 12-year-old children with and without histories of severe deprivation in the form of early rearing in large, impersonal institutions in Romania. The children with histories of deprivation had participated in the first ever RCT designed to assess foster care as an alternative to institutional care. The most important finding is that 8 years after the trial ended, children placed in high-quality foster care continued to show fewer signs of both reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder. The BEIP is the first study to examine experimentally the effects of different caregiving environments on signs of attachment disorders in young children and the present study is the longest longitudinal follow-up reported to date. These findings are in keeping with intervention effects noted when the RCT concluded when the children reached 54 months of age, and again at the follow-up conducted when they were 8 years old (Smyke et al., 2012). The fact that the positive effects of the intervention remain evident 8 years after the end of the formal intervention (and 10 years after randomization) underscores the importance of early relationships in both preventing the onset of and promoting the resolution of attachment disorders.

Our work also highlights the enduring nature of early deprivation on attachment difficulties. Those children who were ever exposed to institutional rearing had significantly higher levels of both inhibited and disinhibited social behavior than comparison children reared in families since birth. Descriptive studies of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder in adolescence are relatively rare, as the majority of work documenting signs of attachment disorders focus on early childhood. Our study focused on adolescence, and indicates that caregiving disruptions in early life remain detectable on these outcomes at this developmental period, yet it is important to note that these do not necessarily reflect the diagnoses of either reactive attachment disorder or disinhibited social engagement disorder. At a diagnostic level, it is unclear whether these symptoms are most appropriate for capturing the presentation of such disorders, should they exist at this age.

For those placed into foster care, we examined whether the age of original placement, which ranged from 6 to 33 months in this sample, was associated with signs of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder at 12 years of age within the foster care group. We found no evidence of a significant association based on placement before or after 24 months (an age found to be a deflection point in other outcomes from the BEIP [Nelson et al., 2007, 2014]). These results are in keeping, however, with our previous finding that timing of foster placement had no effect on signs of reactive attachment disorder, but differ from our finding that earlier foster placement was modestly related to signs of disinhibited social engagement disorder. Given that by age 12 years, most children in care as usual group had experienced family care via adoption, government foster care, or return to biological families (only 6 children were continuously institutionalized through 12 years), and given that this follow-up was conducted more than 10 years following randomization, the care as usual group versus foster care group contrasts are in and of themselves demonstrations of timing effects, that is, caregiving alterations before the age of three years led to changes in developmental trajectories.

However, in addition to the importance of early experience in predicting signs of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder in adolescence, this study also indicated that there may be a role of subsequent life events in explaining observed variation in signs of these two attachment disorders. The evidence that greater time in institutional care predicted signs of both reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder, even after accounting for earlier variations in exposure to institutional care, indicates that experiences beyond the early life period may be meaningful in the course and progression of attachment disorders. It may be that although insufficient caregiving in early life is a required criterion for attachment disorders, subsequent caregiving disruptions in middle childhood further predispose to both reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder observed in adolescence—at least for children with severe early life deprivation. Of note, the percent time in institutional care analyses were not simply a proxy for the intervention groups, as most children from both the foster care group and care as usual group were reunited with biological family, placed into government sponsored foster care, or were returned to institutional care over the course of the follow-up period. In addition, the number of placement disruptions, were related to signs of reactive attachment disorder, but not to signs of disinhibited social engagement disorder. We elsewhere have reported that number of disruptions was associated with more behavior problems, lower IQ scores, and poorer coping strategies in this sample at age 12 years (Almas et al., 2016). Thus, the present findings indicate that signs of reactive attachment disorder may also be susceptible to later caregiving disruptions.

Attachment disorders are a relatively new area of systematic research. The vast majority of studies have been conducted in the past two decades, but they have mostly focused on young children. One of the contributions of this investigation is assessing the signs of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder using the same measure in early adolescence that was used in previous assessments when the children were young children. Of course this raises questions of validity, given that these disorders have not been studied nearly as much in this age range, and we do not know the presentation of adolescents diagnosed with reactive attachment disorder or disinhibited social engagement disorder and whether and how this may differ from young children with these disorders. The Disturbances of Attachment Interview, which was used in this study to identify signs of attachment disorders, had not been used previously in children age 12 years or older, though it has been validated extensively when used with younger children. Thus, although the results of the present investigation are compatible with valid findings at younger ages, there is no “gold standard” for assessing disordered attachment at this age to which these findings can be compared. Still, the high internal consistencies of the scales used to assess the constructs of interest and the moderate to strong correlations of scores from this scale in early adolescence with scores obtained at ages 54 months and 8 years provide reassurance that we have remained focused on the construct of interest.

The phenotype of disinhibited social engagement disorder has been studied longitudinally by some investigators (e.g., Hodges & Tizard, 1989; Rutter et al., 2010), but this is the first longitudinal assessment of the emotionally withdrawn/inhibited phenotype of reactive attachment disorder. Despite the moderate to strong correlations with earlier ages, questions remain about how this disorder manifests at the level of clinical presentation, patterns of comorbidity, and core features in early adolescence.

There are limitations to the current study that deserve highlighting. First, beyond issues of validity of the Disturbances of Attachment Interview in early adolescence, we relied on caregiver reports of the children’s behaviors to assess attachment disorders, and we did not include children’s reports. This is, of course, an acceptable method of assessing psychopathology in children, and given the large numbers of children in this sample with intellectual disabilities (see Almas, Degnan, Nelson, Zeanah, & Fox, in press) who appeared not to understand a number of probes, we believe caregiver reports to be preferable in this sample. Third, children are living in different settings, so that reporters include biological parents, adoptive parents, foster parents, and unrelated caregivers in group settings (e.g., caregivers in group homes or institutions). Arguably, the study children have different kinds of relationships with these different individuals, but in every case, we sought to have each child’s primary caregiver report on the child’s behavior. Though each caregiver may bring different biases to bear, in each case, caregivers live with their child and know them well. Previously, we have noted that in comparing the results of outcomes relying on caregiver report and results that involve no opportunity for caregiver bias (e.g., electrophysiology and growth), the patterns of results are similar, increasing our confidence in caregiver reports (Nelson et al., 2014).

Our longitudinal RCT findings replicate and extend earlier cross-sectional reports and the only two previous longitudinal studies (Rutter et al., 2009; Tizard & Rees, 1975), emphasizing the importance of family care in early childhood as a vital preventive measure for both inhibited and disinhibited social behavior. Though this study provides some insight into how, when, and what form of environmental changes may affect the presentation of these disorders in adolescence, future work is needed to understand the differential impact of adverse caregiving environments in early life, when these disorders first emerge, and how later experiences may modify the course.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network on “Early Experience and Brain Development” (Charles A. Nelson, Ph.D., Chair), NIMH (1R01MH091363; Nelson) (F32MH107129; Humphreys), Brain & Behavior Research Foundation (formerly NARSAD) Young Investigator Award 23819 (Humphreys).

Appendix

Reactive attachment disorder interview items

-

1

Has preferred attachment figure

-

2

Interest in engaging with others

-

3Seeks comfort

- Seeks comfort when in need

- Seeks comfort from attachment figure

-

4

Accepts comfort when offered

-

5

Engages in social reciprocity

-

6

Has emotion regulation difficulties and reduced positive affect (reverse coded)

Disinhibited social engagement disorder interview items

-

7

Checks back in unfamiliar places

-

8

Reticence with unfamiliar adults

-

9

Approaches strangers aggressively or intrusively (reverse coded)

-

10

Has physical or verbal overfamiliarity (reverse coded)

-

11

Willingness to depart with stranger (reverse coded)

References

- Almas AN, Degnan KA, Nelson CA, Zeanah CH, Fox NA. IQ at age 12 following a history of institutional care: Findings from the Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Developmental Psychology. doi: 10.1037/dev0000167. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almas AN, Woodbury MR, Papp L, Nelson CA, Zeanah CH, Fox NA. The Impact of Caregiving Disruptions Experienced by Previously Institutionalized Children on Cognitive, Behavioral, and Social Outcomes in Late Childhood. 2016 doi: 10.1111/cdev.13169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Boris NW, Hinshaw-Fuselier SS, Smyke AT, Scheeringa MS, Heller SS, Zeanah CH. Comparing criteria for attachment disorders: establishing reliability and validity in high-risk samples. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:568–577. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200405000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce J, Tarullo AR, Gunnar MR. Disinhibited social behavior among internationally adopted children. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:157–71. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm K. A three year follow-up of attachment and indiscriminate friendliness in children adopted from Romanian orphanages. Child Development. 1998;69:1092–1106. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrova-Krol Na, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van Ijzendoorn MH, Juffer F. The importance of quality of care: Effects of perinatal HIV infection and early institutional rearing on preschoolers’ attachment and indiscriminate friendliness. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2010;51:1368–1376. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Almas AN, Degnan KA, Nelson CA, Zeanah CH. The effects of severe psychosocial deprivation and foster care intervention on cognitive development at 8 years of age: findings from the Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52:919–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason MM, Fox NA, Drury S, Smyke AT, Egger HL, Nelson CA, Zeanah CH. Validity of evidence-derived criteria for reactive attachment disorder: Indiscriminately social/disinhibited and emotionally withdrawn/inhibited types. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50:216–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb W. Psychological privation in infancy and subsequent adjustment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1945;15:247–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1945.tb04938.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges J, Tizard B. Social and family relationships of ex-institutional adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 1989;30:77–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1989.tb00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys KL, Gleason MM, Drury SS, Miron D, Nelson CA, Fox NA, Zeanah CH. Effects of institutional rearing and foster care on psychopathology at age 12 years in Romania: follow-up of an open, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:625–634. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00095-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkman CS, Oosterman M, Schuengel C, Bolle Ea, Boer F, Lindauer RJ. Disturbances in attachment: Inhibited and disinhibited symptoms in foster children. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2014;8:21. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-8-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann S, Breivik K, Heiervang ER, Havik T, Havik OE. Reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder in school-aged foster children - A confirmatory approach to dimensional measures. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-0045-4. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy RJ. Effects of institutional vs. boarding home care on a group of infants. Journal of Personality. 1947;15:233–241. [Google Scholar]

- Miller FG. The randomized controlled trial as a demonstration project: An ethical perspective. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:743–745. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09040538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millum J, Emanuel EJ. Ethics. The ethics of international research with abandoned children. Science. 2007;318:1874–1875. doi: 10.1126/science.1153822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CA, Fox NA, Zeanah CH. Romania’s Abandoned Children: Deprivation, Brain Development, and the Struggle for Recovery. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CA, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Marshall PJ, Smyke AT, Guthrie D. Cognitive recovery in socially deprived young children: The Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Science. 2007;318:1937–1940. doi: 10.1126/science.1143921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG, Marvin RS, Rutter M, Olrick JT, Britner PA. Child-parent attachment following early institutional deprivation. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:19–38. doi: 10.1017/S0954579403000026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG, Rutter M. Attachment disorder behavior following early severe deprivation: Extension and longitudinal follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:703–712. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200006000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsavsky AK, Telzer EH, Shapiro M, Humphreys KL, Flannery J, Goff B, Tottenham N. Indiscriminate amygdala response to mothers and strangers after early maternal deprivation. Biological Psychiatry. 2013;74:853–860. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosterman M, Schuengel C. Autonomic reactivity of children to separation and reunion with foster parents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:1196–1203. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3180ca839f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pears KC, Bruce J, Fisher PA, Kim HK. Indiscriminate friendliness in maltreated foster children. Child Maltreatment. 2010;15:64–75. doi: 10.1177/1077559509337891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provence S, Lipton RC. Infants in institutions. New York: International Univ. Press; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Kreppner J, Sonuga-Barke E. Emanuel Miller Lecture: Attachment insecurity, disinhibited attachment, and attachment disorders: where do research findings leave the concepts? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2009;50:529–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Sonuga-Barke EJ, Beckett C, Bell CA, Kreppner J, Kumsta R, Stevens S. Deprivation-specific psychological patterns: Effects of institutional deprivation by the English and Romanian Adoptee Study Team. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2010;75:1–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2010.00550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyke AT, Dumitrescu A, Zeanah CH. Attachment disturbances in young children. I: The continuum of caretaking casualty. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:972–82. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200208000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyke AT, Koga SF, Johnson DE, Fox NA, Marshall PJ, Nelson CA, Zeanah CH. The caregiving context in institution-reared and family-reared infants and toddlers in Romania. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2007;48:210–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyke AT, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Nelson CA. A new model of foster care for young children: the Bucharest early intervention project. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2009;18:721–34. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyke AT, Zeanah CH, Gleason MM, Drury SS, Fox NA, Nelson CA, Guthrie D. A randomized controlled trial comparing foster care and institutional care for children with signs of reactive attachment disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169:508–514. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11050748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares I, Belsky J, Oliveira P, Silva J, Marques S, Baptista J, Martins C. Does early family risk and current quality of care predict indiscriminate social behavior in institutionalized Portuguese children? Attachment and Human Development. 2014;16:137–48. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2013.869237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tizard B, Rees J. The effect of early institutional rearing on the behaviour problems and affectional relationships of four-year-old children. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 1975;16:16–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1975.tb01872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Dries L, Juffer F, Van Ijzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Alink LRa. Infants’ responsiveness, attachment, and indiscriminate friendliness after international adoption from institutions or foster care in China: Application of Emotional Availability Scales to adoptive families. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24:49–64. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkmar FR. Reactive attachment disorder. DSM-IV Sourcebook. 1997;3:255–263. [Google Scholar]

- Wolkind SN. The components of"affectionless psychopathy” in institutionalized children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1974;15:215–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1974.tb01246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH. Disturbances of attachment in young children adopted from institutions. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2000;21:230–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Nelson CA. The Bucharest Early Intervention Project: Case study in the ethics of mental health research. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2012;200:243–247. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318247d275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Gleason MM. Annual Research Review: Attachment disorders in early childhood–clinical presentation, causes, correlates, and treatment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2015;56:207–222. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Koga SF, Simion B, Stanescu A, Tabacaru CL, Fox NA, Woodward HR. Response to commentary: Ethical dimensions of the BEIP. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2006;27:581–583. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Nelson CA, Fox NA, Smyke AT, Marshall P, Parker SW, Koga S. Designing research to study the effects of institutionalization on brain and behavioral development: The Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:885–907. doi: 10.1017/S0954579403000452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Scheeringa M, Boris NW, Heller SS, Smyke AT, Trapani J. Reactive attachment disorder in maltreated toddlers. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2004;28:877–888. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Smyke AT. Disorders of attachment and social engagement related to deprivation. In: Thapar A, Pine DS, Leckman JF, Scott S, Snowling MJ, Taylor E, editors. Rutter’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 6. London: Wiley-Blackwell; 2015. pp. 793–805. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Smyke AT, Koga SF, Carlson E. Attachment in institutionalized and community children in Romania. Child Development. 2005;76:1015–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]