Abstract

Studies addressing the relationship between women's empowerment and intimate partner violence (IPV) have yielded conflicting findings. Some suggest that women’s economic and social empowerment is associated with an increased risk of intimate partner violence (IPV), arguably because men use often IPV to enforce their dominance and reassert inegalitarian gender norms when patriarchal norms are challenged; other studies suggest the converse. It is important to understand why these findings are contradictory to create a more sound basis for designing both women's empowerment interventions and anti-violence interventions. The aim of this study is to clarify the relationship between women's empowerment and IPV in a setting where gender roles are rapidly changing and IPV rates are high. We examine some of the ways in which the nature of women’s empowerment evolved in six villages in rural Bangladesh during a 12-year period in which surveys have documented a decline of 11 points in the percentage of married women experiencing IPV in the prior year. The paper is based on data from 74 life history narratives elicited from 2011 to 2013 with recently married Bangladeshi women from the six villages, whom other community residents identified as empowered. Our findings suggest that women’s empowerment has evolved in several ways that may be contributing to reductions in IPV: in its magnitude (for example, many women are earning more income than they previously did), in women's perceived exit options from abusive marriages, in the propensity of community members to intervene when IPV occurs, and in the normative status of empowerment (it is less likely to be seen as transgressive of gender norms). The finding that community-level perceptions of empowered women can evolve over time may go a long way in explaining the discrepant results in the literature.

INTRODUCTION

Although the role of gender inequality in fostering intimate partner violence (IPV) is well documented, studies examining the relationship between women’s empowerment and IPV provide mixed evidence as to whether IPV decreases as gender norms become more equitable; many recent studies have documented a positive relationship rather than the negative relationship that one might expect. Most definitions of empowerment involve women’s acquisition of resources, agency and the ability to make strategic life choices in a context of gender inequality (Kabeer, 1998, 1999, 2001; Malhotra and Schuler 2005; Schuler and Islam, 2008). There is also broad agreement in the literature that empowerment is a process, involves awareness and sense of self as well as power (the direct exercise of power and the social norms and conventions that support its inequitable distribution), and operates at multiple levels, including the individual level, in interpersonal relations, and through collective action (Rowlands, 1997, 2005; Kesby, 2005).

Quantitative measures of women's empowerment have included women’s schooling, mobility, access to and control over economic resources (e.g., micro-credit, earnings, assets), and indices of autonomy or roles in decision-making. In a recent systematic review of studies from 41 sites (Vyas and Watts, 2009) household assets and women’s education were generally found to be protective against IPV, but evidence about women’s involvement in income generation was mixed. In other studies, a woman’s control over resources was found to be protective (Dalal, 2011), but earning an income and contributing more than a nominal amount of income to household expenses appeared to put a woman at greater risk of IPV (Anderson, 1997; Hadi, 2000). In contrast, an analysis of two waves of data from the Indian National Family Health Survey found that both financial autonomy and freedom of movement reduces women’s risk of IPV, but not in more gender-stratified settings of north India (Saberwal et al. 2014).

Likewise, studies from Bangladesh have yielded mixed findings regarding the relationship between women's empowerment and IPV, with some evidence that it can vary depending on contextual factors. Female education generally correlates with a lower risk of IPV (Bates et al., 2004; Koenig et al., 2003; Amin et al., 2013), but several studies suggest that forms of women’s empowerment such as earning an income or contributing more than a nominal amount of income to household expenses put a woman at greater risk of IPV (Bates et al., 2004; Amin et al., 2013; Naved and Persson, 2005). Another study found that being engaged in productive activities for fewer than five years was not associated with IPV, while women who were engaged in such activities for more than five years had a significantly lower risk of experiencing IPV (Hadi 2005). A recent study in 60 villages near Dhaka, Bangladesh also found a correlation between women’s work for pay and IPV risk, but only among women who marry earlier or have less education (Heath 2014). Women involved in microcredit programs experienced higher levels of IPV in several studies (Rahman et al., 2011; Bates et al., 2004; Naved and Persson, 2005; Bhuiya et al., 2003) although one analysis suggests this may be attributable to selection bias (Bajracharya and Amin, 2013). The ambivalent findings on the relationship between women’s economic empowerment and IPV may reflect variations in the extent to which women’s economic participation is accompanied by opportunities for them to transcend the internalized oppression that restricts their perceived options (Rowlands 1995).

Indices of a woman’s autonomy/mobility, decision-making power, and control of resources were found to be positively associated with past-year physical violence in a region of Bangladesh that is known to be socially conservative in terms of adherence to longstanding gender norms (Koenig et al., 2003), whereas, in another study in rural Bangladesh, women's autonomy was found to be associated with a lower risk of past-year physical violence (Hadi, 2005). A study using data from the 2007 Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS) found that violence against women increased with their greater involvement in household decision-making (Rahman et al., 2011), as did a recent analysis controlling for endogeneity which used the same data set (Fakir et al., 2016), but another analysis also using the same data set found that an autonomy index comprised of 11 items related to decision-making, attitudes about IPV, and freedom of movement (Rahman et al., 2013) was associated with a reduced risk of IPV.

Similar to what Jewkes, et al. found in the context of female education in South Africa (Jewkes et al., 2002; Jewkes, 2002), research in Bangladesh suggests that men sometimes use IPV to enforce their dominance and reassert inegalitarian gender roles in marriage when women begin to become empowered through micro-finance or income earning (Schuler et al., 1998; Goetz and Gupta, 1996). Jewkes speculates that as women begin to become empowered they may start to question rigid gender roles but that their empowerment may not be sufficient to protect them from the repercussions of this questioning. This theory may explain the positive associations found between various aspects of women’s empowerment and IPV in Bangladesh. However, much of the literature suggesting that women’s empowerment increases Bangladeshi women’s risk of IPV was conducted more than a decade ago, and most of it is based on cross-sectional studies in which women’s empowerment is treated as a static variable. Rapid economic and social changes have been taking place in Bangladesh; for example, progress measured by the United Nations human development indicators (http://hdr.undp.org) and the Millennium Development Goals (www.socialwatch.org; World Bank, 2010) since the early 1990s has been notable particularly with regard to primary schooling, gender parity in education, poverty reduction and a variety of health indicators. Recent analyses from a nationally representative survey of 3909 recently married women suggest that women’s empowerment is now a protective factor against IPV in rural Bangladesh (Bates and Schuler, Unpublished data).

This paper presents recent qualitative findings from six villages where the primary author has been doing research since 1991 (Schuler, Nazneen and Bates, 2013). The findings document a local perception that IPV in these villages has dropped dramatically in recent years, and a comparison of survey data from the six villages in 2002 (N=1212) and 2014 (N=1031) has confirmed this. Between 2002 and 2014, the rate of past-year IPV among all currently married women under age 50 dropped by 11 percentage points, from 36% to 25%; similarly, the percentage of women ever experiencing IPV from the time of their marriage to the time of the survey dropped from 68% to 55%. Additionally, although this could not be demonstrated with time invariant measures of women’s empowerment, the six village findings, like the national findings cited above, suggest that women’s empowerment has evolved from a risk factor to a factor protecting women from IPV (Field and Schuler, Unpublished data).

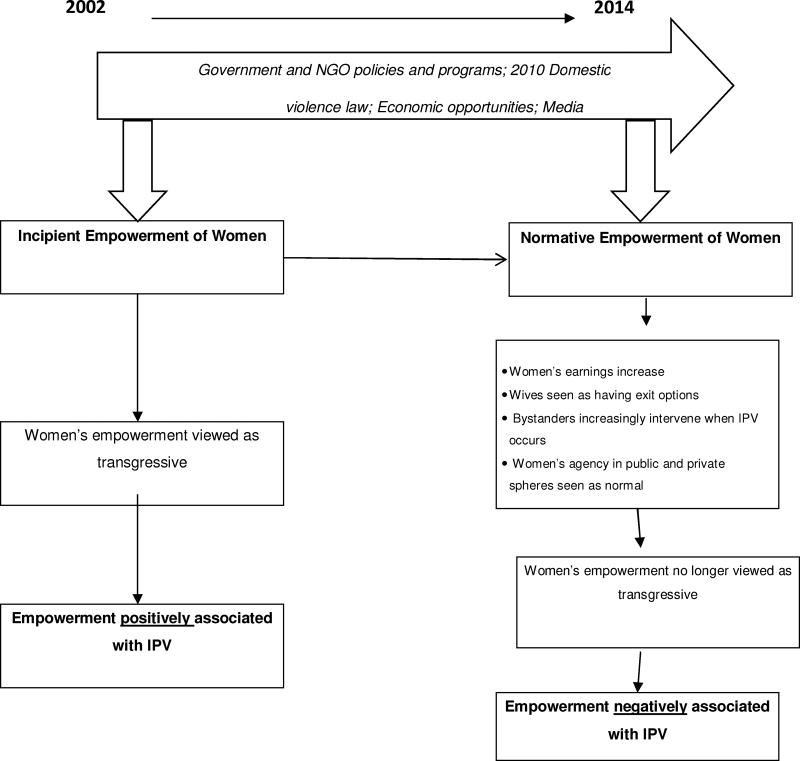

Through life history narratives, the women in the present study discuss the processes through which they became empowered, their experiences of IPV from the time of marriage, and the strategies they have used to avoid or respond to IPV. The aims of the study were: 1) to explore the social processes underlying a decline in rates of IPV between 2002 and 2014; 2) to better understand the ambivalent findings in the literature regarding the relationship between women’s empowerment and IPV; and 3) to explore changes in the nature of women’s empowerment that may explain a recent quantitative finding suggesting that women’s empowerment has evolved from a risk factor for IPV to a protective factor. Our theoretical framework is shown in Figure 1, below. We distinguish between “incipient empowerment”, where women’s enhanced economic and social roles are viewed as transgressive of gender norms and men justify IPV on these grounds, to “normative” empowerment. The conflicting findings in the literature regarding the relationship between women’s empowerment and IPV may reflect contextual differences in the degree to which women’s empowerment is seen as transgressive versus normal across settings and time.

Figure 1.

Evolution of the Relationship Between Women's Empowerment and Intimate Partner Violence in Rural Bangladesh: A Conceptual Framework

METHODS

Sites

The research sites are six villages in Magura, Faridpur and Rangpur Districts in the Western and Northern parts of the country. Although not randomly selected, the villages and the districts in which they are located do not stand out within the context of rural Bangladesh (Bates et. al, 2004). The villages were poor, but not unusually so for rural Bangladesh. Most families had access to television, either owning one or watching at neighbouring homes, and many people, particularly the young, and men, had mobile phones. The villages also were somewhat (but not unusually) socially conservative with regard to gender norms. Several non-governmental organizations (NGOs) were active in each village, working in areas such as micro-finance, primary health care, education, legal awareness and services, and the promotion of gender equity (Schuler, Nazneen and Bates, 2013). Sources of employment for women included garment factories near two villages, a jute mill in one, various construction projects, tailoring (training had been provided), poultry raising (training provided), jobs as school teachers and private tutors, and employment by the NGOs themselves for various village-level initiatives. A substantial number of women from some of the villages had migrated to Dhaka, in most cases to work in garment factories. Some men were working in Dhaka or the Middle East.

Data

The data come from 74 life history narratives (LHN) with women, conducted from 2011 through 2013 as part of a larger, mixed-method study on relationships between women’s empowerment and IPV. The qualitative component was designed to elucidate the social processes underlying these relationships, and local perceptions of these processes. To be eligible for the qualitative component of the study, a woman had to be married between three and 12 years, come from lower-middle or lower class households, based on a rough visual assessment, and be at least somewhat empowered—defined heuristically as above average for the village compared with women from other lower and lower-middle class households in their levels of education, income earning and/or roles in managing family resources, and or having a higher level of education or earning more than her husband. Selection was made by the field researchers based on their own prior knowledge of the women, casual conversations with other women in the community, and brief screening interviews with the women themselves. We excluded women married fewer than two years, as we assumed that new brides would not have had much chance to become empowered. The upper limit on years married was intended to exclude older women, whose risk of IPV is known to be lower. Restricting the LHN sample to women who were relatively empowered might be considered a limitation of the study, but this was a deliberate decision. There is already ample documentation of patriarchal gender relations and IPV among couples where women are not empowered, including in previous phases of our own research. In contrast, there has been little research on the social processes through which women’s empowerment affects IPV risk in Bangladesh.

In the LHNs, women were asked, in a single session lasting about two hours, to tell their own stories, beginning with the details of the marriage itself and continuing to the present. Prompts were used when needed to help focus the story on the topics of empowerment and IPV. An interview guide was created to help the interviewers probe on certain points (e.g., how her husband and in-laws reacted when she first suggested taking up an income-generating activity, how others in the community viewed her and how her husband reacted when others made remarks about her, whether her husband ever seemed to feel threatened by her accomplishments). Questions were often added spontaneously to probe the woman’s specific statements. Field notes were used to record additional detail.

The interviewers were two Bangladeshi women with long experience conducting qualitative interviews, who had worked in the villages on previous studies and had established trust and rapport. The interviews were conducted in Bangla, audio-recorded, transcribed, and translated into English. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of FHI 360 and icddr,b. Verbal informed consent was obtained.

Analysis

The authors analysed the transcripts thematically, reading and re-reading entire transcripts along with field notes to identify and juxtapose salient themes in their narrative contexts. They paid particular attention to characterizing processes of change in the two main variables of interest: women's empowerment and IPV, and to understanding these processes from the perspectives of the actors themselves. The transcripts were also coded in NVivo 9 by two analysts to assemble and evaluate supporting evidence and counterevidence to test and revise interpretations. Coding categories focused on incidences of IPV and the circumstances surrounding them, recourse seeking, interventions and experiences with various intervention mechanisms, processes of empowerment, gender attitudes of the women interviewed, and the women’s perceptions of attitudes about gender and IPV among husbands and extended families, and in communities. Inter-coder reliability analyses were conducted at intervals to ensure the codes were applied consistently. Interpretations and conclusions were vetted with the Bangladeshi interviewers. Results were triangulated with findings from 20 focus groups with men, 13 focus groups with women, and 39 in-depth interviews with men, from which findings are reported elsewhere. These focused on perceived changes in gender roles in the community and the country as a whole, attitudes regarding these changes, village-level trends in IPV, and factors locally perceived to be influencing these trends (Schuler, Nazneen and Bates, 2013).

PRIOR DATA ON WOMEN’S EMPOWERMENT AND IPV IN THE STUDY SITES

The main author, with an evolving local research team that, at the time of this study included three long-time members, has been conducting research on and off in the six villages since 1991. The topics have included gender and women’s empowerment, microcredit programs, perceptions of reproductive health services, child marriage, and attitudes and practices related to IPV. Research methods have included structured surveys with married women, participant observation, focus group discussions, in-depth interviews with adults of all ages, including key informants such as NGO staff and health and family planning workers and life history narratives with women.

During the 1990s and early 2000's, a small number of women in the six villages stood out as being much more empowered than others, both economically and in terms of their mobility and their decision-making roles in their families. Typically these were women from poor households who had taken control of their circumstances in response to their husbands’ failings: the husbands were ill or mentally challenged, abandoned their wives because of polygamy or adulterous relationships, failed at their enterprises, or simply would not work (Schuler, Islam and Rottach, 2010). Because of these women’s dire circumstances, their communities did not censure them for violating purdah norms (norms requiring seclusion of women) by working outside their homes and being more visible in public spaces. (In general, public spaces such as roads and pathways, markets, common areas of the village and public transportation were considered to be the domain of men. Women and adolescent girls were thought to be appropriately confined to homes and courtyards occupied only by relatives unless they were covered up and escorted by a husband or another male guardian.) The impoverished women who went against purdah norms to work were credited for overcoming adversity, but were generally pitied for their lack of provider-husbands. They were not seen as role models for other women. As most were illiterate, the work available to them (in rice processing centres, on road construction crews, as itinerant vendors carrying heavy loads) was often back-breaking, as well as low-status, and they often abandoned it as they grew older, weaker, less desperate for the income, or more concerned that the low social status of the work would undermine their daughters’ marriage prospects. They typically married off their daughters at young ages, wanting them to have the economic security and respectability that they themselves lacked (Schuler, Islam and Rottach, 2010; Schuler and Rottach, 2011).

There was also a larger group of women, who had become somewhat empowered through microcredit programs and/or home-based income-earning activities and whose families, according to the women, acknowledged that they were making economic contributions (albeit very small ones) and included them to varying degrees in decision-making. The majority of these women too were illiterate or, at best, semi-literate. Those in credit programs depended on their husbands' incomes for most daily needs and to pay the small weekly loan instalments, since most of the activities for which they used the loan money did not provide income on a weekly basis (Hashemi, Schuler and Riley, 1996). Often they handed over part or all of the loans to their husbands. If they did manage to save some of the money it was typically used to purchase small treats for their children or to respond to emergencies such as illnesses or food shortages during lean periods of the year (Hashemi, Schuler and Riley, 1996). Beyond the meagre but, to them and their families, important impact of the micro-loans, many of these women ‘learned to talk’ to men and outsiders through their involvement with credit program staff (Hashemi, Schuler and Riley, 1996) and men began to characterize some of them as ‘smart’ or ‘clever’, women they admired but also regarded with ambivalence (Schuler et al., 2006; Schuler, 2007).

This ambivalence sometimes erupted into IPV (Schuler, Hashemi and Badal, 1998). Data from a survey conducted in 2002 in these villages showed high rates of IPV (67% of women ever beaten by husband; 35% beaten in past year) and a statistically significant inverse relationship between IPV and women’s income earning (Bates et al., 2004), as well as an index of empowerment that combined eight indicators (mobility, economic security, ability to make small purchases, ability to make larger purchases, participation in major household decisions, relative freedom from domination by the family, political and legal awareness, and participation in public protests and political campaigning) (Bates and Schuler, Unpublished data)—in other words, in 2002, women who were more empowered were more likely to experience IPV.

CURRENT FINDINGS

By 2011–2013, as the findings below illustrate, the nature of women's empowerment in these villages had evolved to a point where it was much less often seen as transgressive of gender norms and, as suggested by analyses of survey data from 2014 (Field and Schuler, Unpublished data), was less likely to contribute to IPV. Analysis of the LHN data suggests that women’s empowerment, by this time, had four important characteristics that, we argue, discourage IPV: 1) The typical economic contribution of empowered women (both direct and indirect through management of household resources) increased to a point at which men depended on it to maintain a certain standard of living, and acknowledged their wives’ contributions; 2) Women's income earning ability gave them ‘exit options’--in other words they, and their husbands, believed they would be able to support themselves if they left because of IPV; 3) Women's empowerment had become common enough that many people saw it as the norm and praised women for their accomplishments in increasing the prosperity of their households--in other words, women’s empowerment was more often seen as normal than transgressive; and 4) Women were intervening to censure men who engaged in IPV, backed up by NGOs and other community members. The following data from women's life history narratives illustrate how they articulate these characteristics of empowerment and their relationship to IPV.

Starting points and trajectories

Almost all the women in the sample married in their teens, some as young as ages 12–14 (median age at marriage 16.5, similar to that in the 2011 BDHS) (NIPORT et al, 2013). Their current ages were 17–32, with the husband, on average seven years older than the wife. The women’s levels of education ranged from none at all to more than secondary (median 8.5 years). Forty-two of the women reported having more education than their husbands and only 23 said their husbands had more education. This is attributable in part to our study design in that we sought out such women to investigate whether such discrepancies were a source of conflict. In some cases the husbands were illiterate and had to depend on their wives to read documents. In contrast to many of the cases we documented 10–20 years earlier, the dowry was often given to the bride or the couple rather than her in-laws, often some part of it at the time of marriage, in the form of ornaments and/or household necessities and the rest later, in the form of land, livestock or cash. Somewhat surprisingly, 78% of the 74 in the empowered women sample revealed in their narratives that they had experienced IPV at some time in the course of their marriages—more than in the overall village population, where 68% of all married women under age 50 in our 2014 survey reported that they had experienced IPV at some point during their marriages. In the LHNs the women were not asked specifically whether they had experienced IPV in the prior year, but 13% mentioned that they had, 24% said they had not, and 21% did not clearly say. (A much larger proportion--25 %-- of the women in the survey reported prior year IPV.)

For reasons not explored in the study, a disproportionate number of the women had married into households poorer than those of their parents. Twenty-five of the women said their families were wealthier at the time of their marriage and only seven said their husbands’ families were wealthier. Possibly, marrying down was a strategy to minimize dowry demands from the groom’s family, although most of the women said their families gave dowry ‘willingly’. Women’s education was another factor reducing dowry demands, and lower dowries may have enabled parents to provide more support to their daughters subsequent to their marriages.

Many of the women said they were shocked by the poor condition of the husband’s house. In almost all cases, initially these were extended households (containing two or more generations) or extended-joint households (containing two or more generations and two or more brothers with their wives). When they were new brides, some of the 74 women, especially those who were mere children when they married, were treated gently for the initial 1–2 years of marriage, but this was not always the case—some were expected to do hard labor from the first few days and some were subjected to IPV and abuse by in-laws almost immediately. Although many of them were very unhappy and regretted their marriages, typically, the young brides did not try to remove themselves, except to visit their parents, explaining to the interviewers that a woman’s first marriage is her only marriage, and her fate. How much they were actually influenced by this ideology as opposed to worried that a subsequent marriage could turn out to be even worse was often unclear. In any case, in the early years of their marriages, they believed they needed to be married, that remaining in their parental home or striking out on their own was not an option.

Over the years, many of the women’s parents made gifts and loans beyond what they had given as dowry, which the young women often managed to invest and use for income generation. Natal family resources not only helped the young couples economically, but also in many cases gave the women added status with their husbands and in-laws. Couples usually separated from the man’s parents after about two years of co-residence, often at the instigation of the parents, who felt one or more of their married sons was free-loading (depending on the family for support without working and contributing). The wife typically saw economic/residential independence as a pivotal, positive event in the couple’s life, regardless of whether the in-laws had been kind or unkind to her. From then on, what she earned and what her parents gave her would be hers, or the couple’s (often but not always a fine distinction).

Family planning is now well accepted in Bangladesh, and many of the young brides/couples both postponed the first child and practiced spacing after the first birth. This gave young wives more freedom to engage in income generating activities than was the case in previous generations. Several women remarked on this, along with increased opportunities, when asked to explain why women today worked and earned more than their predecessors. Typically, women began their economic empowerment trajectories by saving money and buying (or receiving from natal relatives) a few chickens or a single goat or cow. Some of those with enough education tutored the children of neighbours for a small fee. Some did sewing or embroidery. At some point they began taking micro-loans from one or more of the various NGOs that now work in most villages throughout Bangladesh. Some eventually leased or bought land, bought a rickshaw for their husbands, invested in a shop, or engaged in trade or money-lending. The young women's ideas for income earning strategies typically came from observing other women in their villages, or they received advice from natal relatives or other women. Gradually their husbands grew to appreciate their efforts, trust their judgment, and rely on them. Many of the women also refined their skills in dealing with their husbands to avoid irritating them and gain their cooperation, construing their accomplishments and power as an extension of women's traditional subordination to the well being of the husband and children. Often there was IPV in the relationship, which usually stopped or decreased as time went on.

The following description, spliced from one of the LHNs is quite typical:

You will only get married once… If I have got good things in my fate, if I am destined to have good days, I will be able to improve the financial condition with efforts and hard work, I told myself….In the beginning he was unwilling to give me money. I approached him time and again, I tried to sway his thinking….At one stage he started to leave some money with me…. (After saving for a while,) I bought two hens with 300 taka. From those two hens I got many chickens. I sold the eggs for a good amount of money. I saved that money and the money my husband gave me. Thus I was able to save 3000 taka. With that money I bought a small goat. Later I sold that goat for 7000 taka. I did not keep the money here, I deposited it in my parents' house. Here it was a joint household. For whatever purpose I had invested the money, everyone would get a share of it….He kept on asking me for the money….At one stage he even beat me because of this. Still, I did not lose my patience. I told myself, 'Even if he continues to beat me I am not going to give [him] this money.'…I brought that money back after the separation of the household. I used the money to buy a [rickshaw] ‘van’ for my husband…Van driving involves a lot of hard work…. He was rather angry…. He even stopped taking food…. He even beat me once as I insisted on buying the van…. I have taken loans from BRAC, Ad-din and Grameen…. On one occasion I used the money to buy a mobile phone for my husband…. He works as a van driver, he also works as a day laborer…. If he goes out with the van it is not possible for him to know whether an opportunity for day labor is there or not. Other people cannot inform him. If you have a mobile you can find out about things easily and join a job immediately. Nowadays he does not take any decision without consulting me…. It is now clear to him that I am more intelligent than he…. As he now has come to realize this he neither beats me nor reprimands me…. I don't tell him things directly, nor do I engage in direct argument with him. I persuade him gradually and with patience…. These are the reasons my husband neither beats me nor abuses me verbally…. What I say and what I do, I do for the sake of my family. I always think about what is good for all of us. This is why my husband does not need to beat me. (Age 24)

The resources this woman took advantage of included natal family resources, micro-credit programs, and opportunities offered by local economy, now more vital than it was 10–20 years ago. Now there is adequate demand for chickens, eggs and goats to make raising these animals profitable, as well as demand for transport and unskilled labor.

Below we discuss the four characteristics of empowerment that, we argue, contribute to lower levels of IPV compared with what existed in the 1990s and early 2000s in these villages.

Husbands’ increasing dependence on and recognition of their wives

The economic contributions of women in the six villages have increased, and many husbands now depend on them to achieve a certain standard of living. Empowered women's contributions include not only their own direct earnings, but also joint earnings through their cooperation with their husbands in agricultural production, advice and facilitation of husbands' income earning activities --e.g., by investing their savings and getting loans from NGOs, and management of family resources. Women gave many examples of how their earnings were used for investment, to improve their homes and purchase consumer items, and to support their children’s schooling and buy them clothing and treats.

I talk with the laborers and pay them their wages…. I go there [to the fields] to make sure no one steals anything. I inspect whether the workers irrigate properly, whether they work properly…. Sometimes when there is a sign that the price of rice will increase I advise him not to sell yet. (Age 26)

I was beaten so much after coming to this family that I imagine no woman in this entire world could have been beaten like me by her husband…. I have suffered a lot but I am now getting pleasure from the way it turned out. Now my husband doesn’t do a single thing without consulting me. I tenaciously pursue him until he agrees with what I say…. My husband has become very good now, because he sees that the person he misbehaved with so much and beat so much was unmoved and tenaciously glued herself to the development of the household. (Age 23)

A husband wants this and that from his wife. Suppose the husband tells his wife, ‘Buy me a mobile phone.’ The wife buys it for him. On top of that, the husband tells his wife that he needs some money to buy fertilizer. The wife gives him money then and there. This is how on different occasions a husband wants different things from his wife. The wife meets her husband’s demands. This is why, nowadays, a husband does not beat his wife. (Age 18)

It was also apparent that women were less likely than they had been in the early 1990s to drop out of the labor market as the economic status of their households improved. Along with increases in women's education levels, women's ability to do higher status jobs was improving. The perceived status of women who work for income increasingly depends on the nature of the job and the level of earnings.

Perceived exit options for women

Women—and also men (Schuler, Nazneen and Bates, 2013)—have come to believe that women's income earning ability gives them ‘exit options’--in other words they would be able to support themselves if they left their marriages because of IPV. Although we heard of a few cases, women in fact rarely did leave their husbands, but the existence of this perceived option seems to have given them a level of confidence that they previously lacked. Whether or not they fully believe it, women can at least imagine a life on their own, and they said that social norms had changed such that a woman who left her abusive husband and worked to support herself would be socially accepted. This appears to have increased empowered women’s bargaining power, as they can more realistically threaten to leave an abusive marriage.

Well, I have a good income. That gives me some kind of confidence and sense of self-reliance. Now I do not need to be too concerned about what my husband may do in the future…. I will make use of my assets and will work out ways to live life along with my children. I will have options for bringing up my children, for providing education to them and supporting my own living. (Age 21)

Earlier, women swallowed their husbands’ beatings silently because they didn’t have anywhere to go but their father’s house, but the situation has changed a lot now, and women have many places to go. They can go to Dhaka or to Magura. Nowadays, nobody says anything even if a woman lives alone. Everybody knows they have to survive by working. (Age 23)

Changed norms for women

Women's empowerment has become common enough that many people see it as a norm for women to aspire to (an injunctive norm) and praise them for their accomplishments in increasing the prosperity of their households; women’s empowerment is less often seen as transgressive of gender norms. Women often said that neighbours and relatives often suggested that a woman take up this or that income generating activity, and some of the women in our sample had advised others in this regard. While there were still many women who did not earn cash incomes, most people no longer saw these women as exemplary. There was, however, a tendency to exaggerate the numbers of women earning incomes, and to point to women who had formal jobs such as school teacher, NGO worker or employee of a garment factory, even though home-based economic activities such as livestock raising were much more common.

Nowadays it is not possible to remain dependent only on husband’s income. Both husband and wife now need to earn income. In the family both have equal rights and obligations. (Age 26)

Many other women of this locality go to work in the garment factory where I go. Some women raise cows, some women raise ducks and hens, and some women raise goats. Moreover, some women grow beans and bottle gourds near their houses. They can eat these vegetables, and they also sell them. Few women stay at home without doing anything. Even the women who already have some money earn either by selling paddy or ducks and hens. Only those women who are very lazy stay at home without doing anything. But now such women are almost rare in this locality. (Age 25)

Nowadays, people praise women who are involved in income generating activities…. Everyone is doing something. Everyone is learning by seeing others…. When their husbands ask them for money, they can provide at least a partial amount. This is why wife beating has lessened. (Age 21)

My neighbour, M's wife earns more money than he. Everyone praises her…. M. used to beat his wife but he does not beat her any more. (Age 26)

Speaking out against IPV and intervening to support victims

Whereas, in the past, people were typically reluctant to intervene in cases of IPV, now it is more common, especially among women. In all six villages, we found examples of women intervening to help other women who were abused by their husbands. Of the sixty-three women who spoke about this, fifteen said they had personally intervened in cases of IPV, fifteen said they had not; 33 said people in their community intervene, and 14 said they did not (though some spoke of in-laws intervening). BRAC has provided legal awareness training and some degree of assistance in three villages.

When a man beats his wife, I challenge him, saying, ‘How can you beat her like that--Isn't she another human with flesh and blood? Not only will she be hurt by your beatings but you will have to pay for it eventually.’ I do not say it angrily, I just say it in a soft tone so he understands. …He needs to distinguish between right and wrong….We say these things for a fair society, so that little children will not learn these foul things. (Age 27)

I said, ‘Why do you hit your wife like this every day? There is a law for violence against women. If she files a case against you, you will have to spend six years in jail!’…Most women of our neighbourhood go to protest. Everyone steps forward to try to make the man understand so he does not hit his wife again. Some women warn him about the law on violence against women. They threaten him, saying, ‘If you hit her again we will report it to the police!’ (Age 21)

I intervene to stop beating. I also speak to the boy to make him understand. I talk to his parents to make them understand that it was their mistake to get the boy married at so early an age….’ [I say] Do not beat your wife. It is not your right to beat your wife. If she is at fault, talk to her and make her understand. People in the society will not appreciate you if you beat your wife….If you mix with good people and learn good things, you will no more beat your wife.’ (Age 22)

Then the neighbours came and stopped him. They said, ‘Why are you hitting her? She is an educated girl. She knows and understands everything!’ (Age 22)

When I was in my nutrition job, I would face such situations regularly. I talked to so many men to make them understand that it is not right to engage in quarrels and beating. (Age 25)

Here in our village there is a BRAC group (group of women organized by BRAC). They ask women to complain to them if there is an incident of wife beating. They promise they will look into it and resolve it. Many women go there. A woman from our neighbourhood went there and got her problem resolved. (Age 27)

DISCUSSION

The role of gender inequality in fostering intimate partner violence is well documented, but as we elaborate in the introduction, studies examining the relationship between women’s empowerment and IPV provide mixed evidence as to whether IPV decreases as gender norms become more equitable. This qualitative study helps to reconcile the discrepant findings in the literature by documenting women's own perceptions of the relationship between empowerment and IPV in a setting where levels of IPV have dropped. We also propose a conceptual framework for understanding changes in the relationship between women's empowerment and IPV in settings where gender norms are in flux.

Although much of the literature suggests that women’s empowerment is a risk factor for IPV in the context of rural Bangladesh, based on data from this six-village study, we argue that that the nature of women’s empowerment in these villages is changing in ways that now protect them from IPV. We identified four characteristics of contemporary empowerment that the women in the study perceive as deterrents to IPV: 1) women are earning more income than they used to, and men have therefore become more dependent on them, and recognize this; 2) their skills and earnings give them an ‘exit option’ (albeit rarely taken) from abusive marriages; 3) their numbers have reached a critical mass, and discourses about women have changed, such that empowered women are less likely to be perceived as transgressing gender norms; and 4) women have begun to intervene to protect other women from IPV.

In focus group discussions from the same research project, (separate) groups of men and women discussed what they perceived as the factors behind a dramatic decrease in IPV that they believe is taking place in their villages (AUTHORS, 2013). We suggest that the forms of women’s empowerment described here constitute some of the mechanisms through which the more distal factors discussed in our focus groups and identified in other studies translate into reduced IPV. Among these factors are: 1) economic opportunities from planned interventions such as microcredit and employment created by NGOs, as well as ‘secular’ trends such as rural industry, agricultural intensification and diversification, and increased vitality of local markets which have enabled women to increase their economic participation and earnings and create exit options from abusive marriages; 2) education (influenced by the Universal Primary Education Act of 1990 and secondary school stipends provided by the government) which has enabled women to take on new forms of employment and informal income generation; 3) family planning, which has freed up time for women to generate income (and the scale of women’s economic activity has contributed to its perception as the new norm); 4) decreased son preference (influenced by behaviour change communication campaigns as well as by daughters’ increased support to their parents), which has encouraged parental investments in daughters, both educational investments and provision of capital and assistance; and 5) community-based and national (via television) campaigns to discourage IPV and portray it as a violation of both human rights and law, legislation (e.g., the Domestic Violence Protection and Prevention Act, 2010) and assistance from NGOs, all of which have given some women the ideological grounding and courage to resist IPV.

The changes in the nature of women’s empowerment described here are not necessarily the primary factors driving the decrease in IPV in these villages. More likely, women’s empowerment interacts with other factors to lessen IPV. For example, improvements in the rural economy have reduced the amount of poverty, which often, but not always, has been found to be a risk factor for IPV Vyas and Watts, 2009; Jewkes, 2002) including in Bangladesh (Bates et al., 2004), and which is perceived to be a risk factor in our research sites (Schuler, Nazneen and Bates, 2013).

Notwithstanding the reductions we measured, IPV persists in the research sites. Even in 2014, 25% of women in the six villages experienced violence during the prior year. Variations in other factors associated with IPV, such as education and household economic status, in the level of empowerment and the extent to which each of the four characteristics of contemporary empowerment pertained in individual cases, in the women's relative skill in underplaying their empowerment to protect the husband's ego, and in the psychological make-up of husbands may explain why some women continue to be subjected to IPV even as gender norms evolve.

Analysing qualitative interview data from 2006 and 2008 with rural Bangladeshi women associated with four social mobilization organizations, Kabeer (2011) presents evidence of several forms of empowerment: improvements in the women’s material positions, recognition as breadwinners, increased self-confidence and sense of rights, and an expansion of their social relationships and power to act collectively. She quotes several women who maintained that IPV had decreased in their communities, and cites instances of group protests against IPV and other forms of violence against women. Kabeer contrasts NGOs engaged in social mobilization with those focused more narrowly on economic assistance, such as microcredit. When women gain a sense that IPV is unjust, she argues, they may be more likely to resist it, either verbally, or by seeking informal assistance, informal mediation or legal redress. Abused women who seek recourse are more likely to receive support in a community that has been mobilized and sensitized to women’s rights issues--in other words, where attitudinal change has begun to occur such that IPV is no longer perceived as acceptable.

In our study sites, attitudes condoning men's violence against their wives were changing both because of NGO efforts to mobilize women and because of exposure to media and increased awareness of laws against domestic violence (Schuler, Nazneen and Bates, 2013). Intensive social mobilization by NGOs such as those Kabeer describes is not widespread and our findings suggest that, however desirable, intensive social mobilization efforts are not always be necessary for erosion of the norms supporting IPV to occur. Anti-violence messages are also promoted through media, including through TV dramas on the theme of IPV, and these have become very popular. Our findings illustrate that economic empowerment can also strengthen women’s sense of their rights, at least when women are also exposed to ideas that challenge patriarchal norms. We agree that social mobilization against IPV in communities is valuable and should be expanded, but we disagree with the implication that positive change will not occur until it is undertaken on a very large scale. Other types of interventions may also create opportunities to address IPV. Kabeer (2011) does note that alternative forms of association among women have also come to exist in other contexts such as that of market-driven employment (e.g., in the garment industry), and in local government and social service delivery systems (e.g., health and family planning programs) and, we would add, in micro-credit programs.

A nationwide survey of violence against women in 2011 by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) found very high levels of physical violence (BBS, 2013); 26.4% reported by currently married rural women over the prior 12 months. A similar survey conducted in 2015 (BBS 2015) measured a drop of 5.4 percentage points, to 20.8%. Our own surveys with all married women under age 50 in the six villages (a much smaller sample, with a much longer period of time between surveys) measured a decrease in the percentage of women reporting IPV during the prior year from 36% in 2002 to 25% in 2014 (Field and Schuler, Unpublished data), confirming local perceptions that IPV had decreased in these sites (Schuler, Nazneen and Bates, 2013). Thus, there is reason to be cautiously optimistic that IPV in Bangladesh has begun to drop.

Analyses of the six village survey data also suggest that some dimensions of empowerment are associated with a lower risk of IPV—e.g., involvement in family decisions, keeping family accounts, being listened to by husband and others in the family, and making certain types of purchases without permission--while others are associated with a higher risk—e.g., certain forms of mobility and small purchases. This appeared to be the case both in 2002 and 2014 (Field and Schuler, Unpublished data). Additionally, qualitative findings from interviews with men between 2011 and 2014 pointed to several emergent aspects of women’s empowerment that men perceived as provocative and transgressive: their presence in the public sphere (particularly in markets, previously off-limits), and controlling, disrespecting, defying or arguing with husbands (Schuler et al., 2017).

CONCLUSION

As Sabarwal and colleagues (2014) have demonstrated, relationships between IPV and specific dimensions of women's autonomy, or empowerment, vary depending on the social context. Results from the present study suggest that relationships between IPV and empowerment vary across time as well as across social contexts. The social meanings of specific empowerment dimensions evolve as forms of empowerment that were "incipient" (Figure 1), and relatively uncommon, become normative. The discrepant findings in the literature regarding the relationship between women's empowerment and IPV, therefore, likely reflect more than just methodological limitations and variations in studies. It may reflect shifting social dynamics and meanings in settings where gender norms are in flux. They may also reflect underlying inconsistencies among researchers in defining empowerment and contextual variations in the extent to which opportunities exist for women to transcend internalized oppression, alter their perceptions of their capacities and rights (Rowlands 1995), and form social affiliations to challenge social inequality (Kabeer 2011). In a relatively traditional social context such as rural Bangladesh, the concept of personal autonomy may be less salient than that of affiliation in characterizing women’s empowerment (Kabeer, 2011).

It remains to be seen if the evolution of women’s empowerment from a risk factor to a protective factor against IPV is occurring throughout Bangladesh. Further research can help to ascertain this. To better understand the roles of various combinations of policy interventions in altering this relationship, researchers will need to employ nuanced definitions of empowerment that include subjective and collective aspects as well as more commonly used measures of women’s economic and decision-making roles. Study designs should also address differences in the effects of women’s empowerment (and various dimensions of it) on IPV across various social contexts.

We can only hope that the BBS survey findings cited above represent the beginning of a decline in IPV prevalence in Bangladesh, that if government and NGOs continue the policies and interventions that have already been initiated, women’s empowerment will eventually become normative throughout the country, that other risk factors, such as poverty and low education, will also continue to diminish, and that the six villages in this study will eventually prove to represent a stage in the decline of IPV in Bangladesh, not an aberration.

Evidence regarding the relationship between women's empowerment and intimate partner violence is generally inconclusive.

In a conceptual framework resolving this contradictory evidence, empowerment evolves from "incipient" to "normative".

Qualitative evidence suggests the nature of women's empowerment evolves over time.

IPV appears to decrease when women's empowerment becomes normative.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Sultan Hafeez Rahman, executive director, and Dr. Minhaj Mahmud, director of research of the BRAC Institute for Governance & Development (BIGD), BRAC University, research team members Shamsul Huda Badal, Khurshida Begum, Shefali Akter and Mossabber Hossain, and Rachel Lenzi and Ansley Lemons of FHI 360 for their assistance in data analysis.

FUNDING

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01HD061630.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS

The author(s) declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Adnan MSF, Anjum A, Bushra F, Nawar N. The endogeneity of domestic violence: Understanding women empowerment through autonomy. World Development Perspectives. 2016;2:34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K. Gender, status, and domestic violence: an integration of feminist and family violence approaches. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1997;59:655–669. [Google Scholar]

- Bajracharya A, Amin S. Microcredit and domestic violence in Bangladesh: An exploration of selection bias influences. Demography. 2013;50(5):1819–1843. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0226-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Report on violence against women survey 2011. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics; Dhaka: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bates LM, Schuler SR, Islam F, Islam K. Socioeconomic factors and processes associated with domestic violence in rural Bangladesh. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2004;30(4):190–199. doi: 10.1363/3019004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates LM, Schuler SR. Unpublished data A. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya M, Bedi AS, Chhachhi A. The endogeneity of domestic violence: Understanding women empowerment through autonomy. World Development Perspectives. 2011;39(9):1676–1689. [Google Scholar]

- Bhuiya A, Sharmin T, Hanifi S. Nature of domestic violence against women in a rural area of Bangladesh: Implications for preventive interventions. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. 2003;21(1):48–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal K. Does economic empowerment protect women from intimate partner violence? Journal of Injury and Violence Research. 2011;3(1):35–44. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v3i1.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakir AMS, Anjum A, Bushra F, Nawar N. The endogeneity of domestic violence: Understanding women empowerment through autonomy. World Development Perspectives. 2016;2:34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Field S, Schuler Unpublished data B. [Google Scholar]

- Goetz A, Gupta R. Who takes the credit? Gender, power, and control over loan use in rural credit programs in Bangladesh. World Development. 1996;24(1):45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hadi A. Prevalence and correlates of the risk of marital sexual violence in Bangladesh. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2000;15(8):787–805. [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi SM, Schuler SR, Riley AP. Rural Credit Programs and Women's Empowerment in Bangladesh. World Development. 1996;24(4):635–653. [Google Scholar]

- Heath R. Women's access to labor market opportunities, control of household resources, and domestic violence: evidence from Bangladesh. World Development. 2014;57:32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Levin J, Penn-Kekana L. Risk factors for domestic violence: findings from a South African cross-sectional study. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55(9):1603–1617. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes Rachel. Intimate partner violence: causes and prevention. The Lancet. 2002;359:1423–29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08357-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer N. Between affiliation and autonomy: Navigating pathways of women's empowerment and gender justice in rural Bangladesh. Development and Change. 2011;42(2):499–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7660.2011.01703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer N. Money can't buy me love? Re-evaluating gender, credit and empowerment in rural Bangladesh. Institute of Development Studies; Sussex, UK: 1998. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer N. Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Development and Change. 1999;30:435–464. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer N. conflicts over credit: Re-evaluating the empowerment potential of loans to women in rural Bangladesh. World Development. 2001;29(1):63–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kesby M. Retheorizing empowerment-through-participation as a performance in space: Beyond tyranny to transformation. Signs. 2005;30(4):2037–2064. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig MA, Ahmed S, Hossain MB, Mozumder AB. Women's status and domestic violence in rural Bangladesh: individual- and community-level effects. Demography. 2003;40(2):269–88. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra A, Schuler SR. Women's Empowerment as a Variable in International Development. In: Narayan, Deepa, editors. Measuring Empowerment: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), Mitra and Associates, and ICF International. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2011. NIPORT, Mitra and Associates, ICF International: Dhaka; Calverton, Maryland: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), Mitra and Associates, and Macro International. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2007. National Institute of Population Research and Training, Mitra and Associates, and Macro International; Dhaka, Bangladesh and Calverton, Maryland, USA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Naved R, Persson LA. Factors associated with spousal physical violence against women in Bangladesh. Studies in Family Planning. 2005;36:289–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2005.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M, Hoque MA, Makinoda S. Intimate Partner Violence Against Women: Is Women Empowerment a Reducing Factor? A Study from a National Bangladeshi Sample. Journal of Family Violence. 2011;26:411–420. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M, Nakamura K, Seino K, Kizuki M. Does Gender Inequity Increase the Risk of Intimate Partner Violence among Women? Evidence from a National Bangladeshi Sample. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e82423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowlands J. Empowerment examined. Development in Practice. 1995;5(2):101–107. doi: 10.1080/0961452951000157074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowlands J. Questioning Empowerment: Working with Women in Honduras. London: Oxfam; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sabarwal S, Santhya K, Jejeebhoy S. Women's autonomy and experience of physical violence within marriage in rural India: evidence from a prospective study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2014;29(2):332–347. doi: 10.1177/0886260513505144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler SR, Islam F, Boender C, Islam K, Bates LM. Health and Development Policies and the Emerging "Smart Woman" in Rural Bangladesh: Local Perceptions Working Papers on Women in International Development. East Lansing, MI: Women and International Development Program, Michigan State University; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schuler SR, Islam F. Women's acceptance of intimate partner violence within marriage in rural Bangladesh. Studies in Family Planning. 2008;39(1):49–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler SR, Hashemi SM, Badal SH. Men's violence against women in rural Bangladesh: undermined or exacerbated by microcredit programmes? Development in Practice. 1998;8(2):148–157. doi: 10.1080/09614529853774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler SR. Rural Bangladesh: Sound Policies, Evolving Gender Norms and Family Strategies. In: Lewis MA, Lockheed ME, editors. Exclusion, Gender and Education: Case studies from the developing world. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development; 2007. pp. 179–203. [Google Scholar]

- Schuler SR, Islam F, Rottach E. Women's empowerment revisited: A case study from Bangladesh. Development in Practice. 2010;20(7):840–854. doi: 10.1080/09614524.2010.508108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler SR, Rottach E. Why does women's empowerment in one generation not lead to later marriage and childbearing in the next? Qualitative findings from Bangladesh. [accessed 1/16/2014];Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 2011 42(2) Social Watch. www.socialwatch.org. [Google Scholar]

- Schuler SR, Lenzi R, Nazneen S, Bates LM. A Perceived Decline in Intimate Partner Violence Against Women in Bangladesh: Qualitative Evidence. Studies in Family Planning. 2013;44(3):243–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2013.00356.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler SR, Lenzi R, Nazneen S, Badal SH. Men’s perspectives on women’s empowerment and its links with intimate partner violence in rural Bangladesh. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 2017 doi: 10.1080/13691058.2017.1332391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Program (UNDP) [accessed 2/25/2013]; http://hdr.undp.org.

- Vyas S, Watts C. How does economic empowerment affect women's risk of intimate partner violence in low and middle income countries? A systematic review of published evidence. Journal of International Development. 2009;21(5):577–602. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Bangladesh Country Assistance Strategy FY 2011 – 2014. The World Bank Bangladesh Country Management Unit, South Asia Region; 2010. [Google Scholar]