Abstract

We experimentally investigate the effects of two different sources of heterogeneity - capability and valuation - on the provision public goods when punishment is possible or not. We find that compared to homogeneous groups, asymmetric valuations for the public good have negative effects on cooperation and its enforcement through informal sanctions. Asymmetric capabilities in providing the public good, in contrast, have a positive and stabilizing effect on voluntary contributions. The main reason for these results are the different externalities contributions have on the other group members’ payoffs affecting individuals’ willingness to cooperate. We thus provide evidence that it is not the asymmetric nature of groups per se that facilitates or impedes collective action, but that it is rather the nature of asymmetry that determines the degree of cooperation and the level of public good provision.

Keywords: Public goods, heterogeneity, privileged groups, inequality, cooperation, punishment

JEL Classification: H41, D63, C92

1. Introduction

Most studies on collective action have focused on situations where agents with identical characteristics interact with each other. When considering social and economic life, however, people generally differ with respect to a variety of characteristics, such as preferences, resources, qualifications, and attitudes which, in turn, can affect their incentives to contribute to a collective good. As such, the existence and formation of homogeneous group environments can be regarded as an exception, rather than the rule. Yet, when, how, and to what degree collective action is affected by inequality among group members is a complex question that has attracted only minor attention so far. Consequently, studying these questions in a systematic manner and gaining a deeper understanding about the determinants and circumstances under which different types of heterogeneity affect collective action is of major importance. In this paper, we therefore experimentally investigate the effects of two different sources of heterogeneity - valuations and capabilities - on the willingness to cooperate in social dilemmas. We study both types of heterogeneity under two conditions, with and without decentralized peer-punishment, and compare them to a benchmark case in which homogeneous agents interact with each other.

Examples for situations in which members of a society or an organization differ along these two dimensions are ubiquitous. Heterogeneity in valuations (preferences) for the public good, for example, occur when parks, swimming pools, dams, or other public facilities provide different benefits to individuals, depending on how far away they live from the site or how often they enjoy the consumption of the public good. Similarly, countries commonly are differently affected by global warming, the exploitation of natural resources such as fish populations, or conventions about international defense alliances. At the same time, individuals may have different capabilities in providing the public good. For example, members of a team working on a joint project often have different task-specific capabilities determining the productivity of their chosen effort. Likewise, in the context of environmental protection, countries may have different qualifications in fighting global climate change, e.g., different opportunities to preserve the rainforest or different technological competencies to avoid carbon dioxide emissions.

While it is legitimate to abstract from heterogeneity to study the underlying logic of collective action problems, we illustrate that this abstraction can also be problematic as it neglects important characteristics of cooperation. Our results indicate that heterogeneity can affect the principle of reciprocity in non-trivial ways by fundamentally altering individuals’ willingness to cooperate within groups. While asymmetric valuations have detrimental effects on voluntary contributions and its enforcement through informal sanctions, we find that asymmetric capabilities have a positive and stabilizing effect on public goods provision. Thus, we provide evidence that it is not the asymmetric nature of groups per se that facilitates or impedes collective action, but that it is rather the specific type of heterogeneity that determines the degree of cooperation and the level of public good provision.

While on the one hand both types of heterogeneity are, to a certain extent, related, on the other hand they differ with respect to the externality contributions have on the other group members’ payoffs. When individuals have asymmetric preferences, benefits from the public good differ between group members, but are independent of who makes a contribution. In contrast, if individuals have asymmetric capabilities benefits are the same for everyone but depend on which group member contributes. While in the first case group members always benefit asymmetrically causing inequalities in payoffs, in the case of heterogeneous capabilities, equal contributions also lead to equal payoffs. This difference influences the distribution of wealth and, given that people also care about relative payoffs, creates different incentives to contribute which, in turn, can also affect allocation.

We investigate these two types of heterogeneity within “privileged groups” which are groups in which at least one group member “has an incentive to see that the collective good is provided, even if he has to bear the full burden of providing it himself” Olson (1965, p.50). While the main message of our paper is not exclusive to privileged groups but also applies to heterogeneous groups more generally, there are several reasons why these groups are of special interest. First, many groups facing the problem of providing public goods can be regarded as being privileged, e.g., in the case of commons-based peer productions such as Linux (Benkler, 2002), attempts to stop overexploitation of natural resources, or the fight against international terrorism.1 Second, especially in privileged groups people’s willingness to (conditionally) cooperate might be affected in important ways. The reason is that contributions by others are not necessarily reciprocated if they do not entail an individual sacrifice, making it hard to unequivocally identify them as nice acts (Glöckner et al., 2011). Finally, although the free-rider problem is mitigated in privileged groups because at least some amount of the public good is voluntarily provided, there will still be underprovision as long as some members find it optimal not to contribute.

Because in collective action problems private and social marginal benefits diverge, relying on voluntary provisions typically leads to an inefficient underprovision of the public good (Samuelson, 1954; Olson, 1965; Hardin, 1968). Different institutional solutions have been proposed to overcome this problem (see Chen, 2008, for a survey). In the experimental literature, a commonly used institution to improve collective action is decentralized peer punishment. However, while punishment has shown to be very effective in promoting public good contributions in homogeneous settings (Gächter and Herrmann, 2009; Chaudhuri, 2011), evidence from heterogeneous groups is rather sparse and inconclusive.2 In such environments, it is not clear whether punishment and related mechanisms work similarly effectively. As argued by Reuben and Riedl (2013), one reason for this is that in asymmetric settings, different fairness concepts can imply different contribution norms which, in turn, can have detrimental effects on voluntary contributions and enforcement of cooperation. In contrast, in homogeneous environments, different fairness norms such as efficiency, equality, and equity all lead to one “coinciding focal norm” facilitating cooperation and its enforcement. To study these effects in our context, we compare our experimental treatments under two complementary situations: one in which punishing other group members is possible and one in which informal sanctions are absent.

Most closely related to our work is a study by Reuben and Riedl (2009). In their experiment, they also compare privileged groups of heterogeneous valuations to homogeneous groups when punishment is possible or not. They find that without punishment privileged groups contribute more, but once punishment is possible they lose their privileged status contributing less than homogeneous groups. They conclude that the asymmetric nature of groups makes the enforcement of cooperation through informal sanctions harder to accomplish. While our results in the valuation treatment are largely in line with their findings, in our additional treatment of heterogeneous capabilities results are strikingly different. This enables us to demonstrate that it is not the asymmetric nature of groups per se that facilitates or impedes collective action, but that it is the specific type of heterogeneity that determines people’s willingness to cooperate within groups. In particular, our results imply that heterogeneity only has detrimental effects on voluntary contributions if it is accompanied by an asymmetric payoff structure, highlighting the importance of payoff equality on cooperation and coordination within groups.

So far, most previous studies that investigate the effects of heterogeneity on public good provision also have made the payoff structure asymmetric by analyzing inequality in endowments3 or preferences.4 The crucial point of studying capability differences is that it allows us to investigate the effects of heterogeneity on public goods provision without destroying the symmetry of the payoff structure. In the experimental literature, we are only aware of two studies (Noussair and Tan, 2011; Fellner et al., 2011) that implement capability heterogeneity in a similar manner as we do. However, none of them investigate privileged groups and none of them analyze the mere effect of capability heterogeneity as they do not compare behavior to groups of homogeneous capability. Furthermore, we are not aware of any study that compares differences in capabilities and preferences vis-a-vis. Shedding light on the differences between these two related types of heterogeneity is the major goal of this study.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, the experimental design and the behavioral predictions are described. Section 3 presents the results of the experiment. Section 4 concludes.

2. The Experiment

2.1. Experimental Design

The underlying decision situation behind our experiment is a standard linear public goods game. Subjects are randomly assigned to one of three experimental treatments, which differ with respect to the group members’ characteristics (see below). In each treatment, participants are matched into groups of three, playing the public goods game for twenty consecutive periods with a surprise restart after ten periods (compare Andreoni, 1988; Croson, 1996). Group composition is kept constant across all twenty periods using a partner-matching design. At the beginning of each period, all group members i ∈ {1, 2, 3} receive an endowment of 20 tokens.5 During the first ten periods of the experiment, the game only consists of a contribution stage in which participants simultaneously decide how many tokens of their endowment they want to contribute to the public good and how many tokens they want to keep for themselves. In the last ten periods, the contribution stage is followed by a decentralized punishment stage.6

Importantly, in addition to our benchmark treatment in which all group members have the same characteristics, in the other two treatments group members differ with regard to the benefit they receive from their own and their group members’ contributions. In one treatment, they differ with respect to their valuation of the public good δi. In the other treatment they differ with respect to their capability ai determining the marginal effect of their contributions. As such, a subject’s effective contribution to the public good depends on two factors: (1) the individual’s nominal contribution ci ∈ [0, 20], and (2) the individual’s capability ai. Hence, every token contributed to the public good by subject j increases the earnings of group member i by δi · aj tokens. Any token not contributed to the public good increases the individual’s own payoff by one token (leaving the other group member’s payoff unchanged). Without punishment, subjects’ monetary payoff at the end of each period is given by

| (1) |

where the amount of public good provision is given by the sum of effective contributions.

In the punishment stage, each participant i simultaneously decides how many punishment points pij ∈ [0, 10] she wants to assign to each other group member j. Each punishment point assigned reduces the earnings of the punished group member by three tokens and costs the punisher one token. At the end of each period, group members are informed about the total number of punishment points received by other group members and their earnings from this period. With punishment, in each period earnings are given by

| (2) |

In our baseline treatment (Base), all three group members receive the same endowment of 20 tokens, benefit to the same extent from the public good δi = 0.5, and have the same capability of providing the public good ai = 1. In the other two treatments there are two types of players: l- and h-types. In particular, at the beginning of the experiment in each group one randomly selected member is assigned the role of a h-player and the two non-selected group members are assigned the role of l-players. While in both treatments the latter have the same characteristics as subjects in the baseline treatment (δl = 0.5; al = 1), in the valuation treatment (Val) h-players are assigned a valuation of δh = 1.5, and in the capability treatment (Cap) they are assigned a capability of ah = 3. Importantly, the h-players’ monetary incentives are completely identical in both treatments. Their marginal benefit from contributing one token to the public good is given by and respectively. The assignment of types is kept constant throughout all 20 periods. All of this information is known by all participants in the experiment. Additionally, at the end of each period subjects receive feedback about individual contributions and payoffs of each other group member, i.e., in all treatments subjects learn how much each type contributed and earned. For a summary of the three treatments, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Experimental treatments

| Treatment | Type | Endowment | Valuation δi | Capability ai | # Groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | 3 x l-player | 20 | 0.5 | 1 | 15 |

| Val | 2 x l-player | 20 | 0.5 | 1 | 16 |

| 1 x h-player | 20 | 1.5 | 1 | ||

| Cap | 2 x l-player | 20 | 0.5 | 1 | 15 |

| 1 x h-player | 20 | 0.5 | 3 | ||

The difference between Val and Cap arises from the different externalities contributions have on the group members’ payoffs, i.e., l- and h-players in Val and Cap benefit differently from contributions made by h- and l-players, respectively. This is illustrated in Table 2. Columns 2 and 3 show marginal benefits ΔπPG l- and h-players receive from the public good when l-types increase their contributions by one unit, Δcl, respectively. Columns 4 and 5 display the same effect only for the case when h-types change contributions by Δch. As can be seen, in Val public good benefits differ between l- and h-players (0.5 vs. 1.5) but do not depend on which player type contributes. In contrast, in Cap public good benefits are always the same for l- and h-players but depend on which type contributes (0.5 if l-players contribute and 1.5 if h-players contribute). While in both treatments l-players may indirectly benefit from the h-players’ increased incentives of contributing, in Cap they additionally benefit from the fact that h-players’ contributions are more valuable.

Table 2.

Externalities and payoff consequences

| Treatment | Δcl | Δch | Payoffs πl, πl, πh [∑ πj] given contributions of cl, cl, ch | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0,0,0 | 20,20,20 | 0,0,20 | 20,0,0 | |||||

| Base | 0.5 | - | - | - | 20,20,20 [60] | 30,30,30 [90] | 30,30,10 [70] | 10,30,30 [70] |

| Val | 0.5 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 20,20,20 [60] | 30,30,90 [150] | 30,30,30 [90] | 10,30,50 [90] |

| Cap | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 20,20,20 [60] | 50,50,50 [150] | 50,50,30 [130] | 10,30,30 [70] |

To illustrate how these different effects translate into outcomes, the last four Columns of Table 2 display players’ payoffs for certain combinations of l- and h-players’ contributions (numbers in square brackets display social efficiency measured by the sum of all payoffs). When everybody free rides payoffs and social efficiency are the same for all players and treatments. If, however, at least one contribution exceeds zero, efficiency and the distribution of payoffs depend on the treatment and the contributor’s type. In Base, differences in contributions translate one-to-one into differences in payoffs, and efficiency does not depend on which group member contributes. In Val, the distribution of payoffs depends on which player type contributes, whereas for efficiency this does not matter. While contributions made by h-players increase their own payoff without changing income differences within a group, contributions made by l-players decrease their own income and increase income inequality to their disadvantage. As a result, irrespective of the h-player’s contribution, equality in payoffs can only be reached if both l-players free ride. In Cap, in contrast, the distribution of payoffs only depends on nominal contributions but not on the players’ type, i.e., irrespective of the subjects’ capability, (un)equal contributions lead to (un)equal payoffs. For efficiency, however, the contributor’s type is important as h-players’ contributions are worth more for the group.7

In summary, the only difference across treatments is the absence or presence of an h-player and, in the latter case, whether the h-player has a higher valuation or a higher capability than the other two group members. Thus, by comparing our three treatment conditions, we can investigate the effect of different sources of heterogeneity on contribution behavior depending on whether the possibility to punish is available or not. In the next section, we discuss how the differences between both types of privileged groups might affect behavior.

2.2. Behavioral Predictions

Generally, if subjects are fully rational and only interested in maximizing their monetary payoffs, if δi · ai < 1, then in the stage game the dominant strategy for subject i is to completely free ride and contribute nothing to the public good. If, however, δi · ai > 1, then full contribution becomes the dominant strategy. Thus, nobody is predicted to contribute in Base. The same prediction can be made for l-types in Val and Cap. In these treatments, however, it is strictly dominant for h-types to contribute their entire endowment as their individual return of contributing strictly outweighs the corresponding costs which, in turn, also increases their own material payoff. Groups in Val and Cap can hence be characterized as being privileged in the sense of Olson (1965), as one member in each group has an individual material incentive to provide the public good. Introducing punishment does not change the standard predictions made so far. Since punishment is costly, selfish individuals are predicted to not assign any punishment points in the second stage. By the logic of backward induction, this is anticipated by group members in the first stage and, thus, they do not change their contribution behavior as punishment is not credible.

There are now, however, many studies indicating that many people are not solely motivated by monetary incentives, but also care about the well-being of others. For example, even when nobody is predicted to contribute anything, evidence from previous public good experiments suggest that there is some positive amount of voluntary cooperation, even in anonymous oneshot interactions (Gächter and Herrmann, 2009; Chaudhuri, 2011). A variety of models of other-regarding preferences (cf. Fehr and Schmidt, 1999; Bolton and Ockenfels, 2000; Charness and Rabin, 2002; Dufwenberg and Kirchsteiger, 2004; Falk and Fischbacher, 2006) have been established that can explain behavior observed in the laboratory and in the field (cf. Sobel, 2005; Fehr and Schmidt, 2006, for an overview). In the following, we discuss implications such other-regarding preferences have on contribution behavior in our experimental setting.

In the baseline treatment (Base), given that people are motivated by inequality aversion or reciprocity, the public goods problem turns into a coordination problem with multiple Pareto ranked equilibria (cf. Rabin, 1993). Given the right beliefs about other people’s contributions, individuals act as conditional cooperators and any amount of cooperation can be sustained in equilibrium. Yet, as argued by Fehr and Schmidt (1999), coordination on high contribution levels is more likely when the possibility to punish free riders is available. The reason is that reducing income differences by punishing low contributing group members becomes a credible motivation when people also care about relative incomes.

In Cap the same logic of matching contributions applies. The only distinction is that the standard predictions for l- and h-players are different which lead to very unequal payoffs (compare Column 8 in Table 2). As a result, l-players have an incentive to increase contributions to reduce advantageous inequality, and h-players have an incentive to decrease contributions to reduce their disutility from earning less than their group members.8 Yet, even if l-players are completely selfish they may have a strategic incentive to contribute if that avoids envious h-players to reduce their contributions. To see this note that l-players have net costs of contributing of 0.5, but that h-players’ contributions yield benefits of 1.5. Furthermore, since h-players’ contributions are worth more, withholding contributions can work as an implicit punishment mechanism reducing own and the l-players’ payoffs by 0.5 and 1.5 points, respectively. Hence, while each level of contributions can be sustained in equilibrium when agents care for relative payoffs, given the additional characteristics of this treatment we expect contributions to be higher compared to Base.

In Val, in contrast, inequality aversion does not change the predictions made by the standard model of purely selfish agents. The reason is that l- and h-players are equally well off when following their payoff maximizing strategy of free riding and full contributions, respectively (compare Column 8 in Table 2). Deviating from these strategies would decrease the player’s own payoff and either increase (in the case of l-players) or leave unchanged inequality (in the case of h-players). In addition, also the strategic incentives for l-players to contribute are much weaker compared to Cap. There are two reasons for that. First, the threat of h-players to reduce their contributions is much weaker as they never earn less than their group members, i.e, they have no inequality motive to punish others by withholding contributions. Second, even when reducing contributions, the consequences for l-players are less severe as payoffs are only reduced by 0.5 points compared to 1.5 in Cap. Besides that, compared to the other two treatments, introducing punishment is predicted to have less of a bite. The reason is that even when getting punished, l-players might be reluctant to increase contributions as this would benefit h-players disproportionately leading to increased inequality. This, in turn, might cause h-players to refrain from punishment in the first place if they expect it to be less effective. The asymmetry in the payoff structure further suggests a higher degree of antisocial punishment (punishment of high contributors) towards h-players as this offers an opportunity for l-players to reduce inequality even if the former contribute more.

Table 3 summarizes the predictions for different prominent guiding principles from the literature. It shows that payoff maximization as well as efficiency concerns do not predict any differences in voluntary contributions between both types of privileged groups. When individuals also care about relative payoffs, differences between treatments may occur. In particular, as discussed above, we expect contributions to be higher in Cap than in Val. We further expect punishment to have a much weaker effect on increasing cooperation in Val compared to the other two treatments.9

Table 3.

Behavioral predictions for the stage game without punishment

| Treatment | Maximizing own Payoff | Maximizing Efficiency | Minimizing Inequality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base | |||

| Val | |||

| Cap |

2.3. Experimental Procedure

The experiment was conducted at the Cologne Laboratory for Economic Research (Germany). Subjects were students from the University of Cologne and were recruited using the online recruiting software ORSEE (Greiner, 2004). Experimental sessions were computerized using the software z-Tree (Fischbacher, 2007). In total, 138 subjects participated in the experiment, 45 in Base and Cap, and 48 in Val, leading to 15, 15, and 16 independent observations, respectively. About half of the subjects were female and about half studied economics. Upon arriving in the laboratory, each subject drew a card which randomly assigned them a seat in the lab. Subjects were also randomly assigned to a treatment, a role (l- or h-type), and a group. At the beginning of the experiment, subjects read the instructions explaining the public goods problem, the incentives, and the rules of the game. To ensure their understanding of the experiment, participants had to answer several control questions about the comparative statics of the game. Only after all participants answered all questions correctly, the experiment started. At the end of the experiment, subjects had to fill out a short questionnaire, after which they were confidentially paid out their earnings in cash. A typical experimental session took about 1.5 hours and subjects earned, on average, 17 Euros (approx. 23 USD).

3. Results

We start our analysis by investigating contribution behavior in the first ten periods without punishment. After that, we analyze how contributions change when subjects are given the possibility to punish each other. In both cases, we first analyze behavior on an aggregated group level and then focus on the individual behavior of l- and h-types. We then study punishment behavior and its consequences for social welfare.

3.1. Voluntary Contributions without Punishment

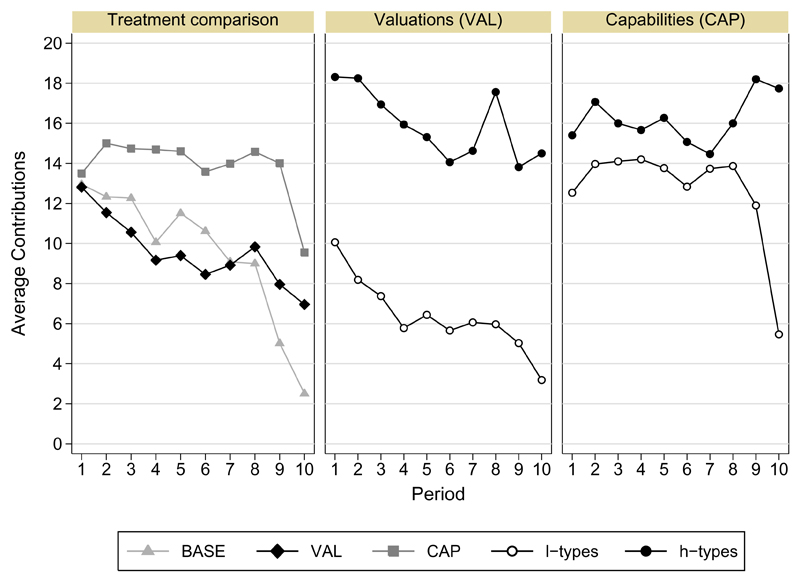

Our main results for the no-punishment condition are summarized in Figure 1. The left panel shows average contributions over time (periods 1-10) for all three treatments. The middle and right panel depicts contribution behavior separated by l- and h-types for the Val- and Cap-treatment, respectively.

Figure 1.

Average contributions over time when punishment is not possible

In line with results from similar public goods experiments (cf. Ledyard, 1995), in Base we find the commonly observed pattern of positive but decreasing contributions over time as indicated by the light gray triangles in the left panel of Figure 1. While in the first round participants contribute around 60% of the social optimum, contributions nearly drop to full free-riding in the last period. A Spearman’s rank-order correlation of contributions on periods corroborates this negative trend of contributions over time (ρ = −0.531, p = 0.007).10

Very similar contribution dynamics are observed in Val (black diamonds). Contributions start at high but decrease to low levels in the final period (ρ = −0.513, p < 0.001). As a result, average contributions are almost identical in both treatments (see Table 4). A non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test cannot reject the hypothesis that distributions are drawn from the same population (p = 0.813).

Table 4.

Average contributions by treatment and type

| Without Punishment |

With Punishment |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| l-player | h-player | total | l-player | h-player | total | |

| Base | 9.5 | - | 9.5 | 16.5 | - | 16.5 |

| (4.6) | - | (4.6) | (3.7) | - | (3.7) | |

| Val | 6.4 | 15.9 | 9.6 | 10.3 | 18.0 | 12.8 |

| (5.2) | (4.3) | (4.1) | (6.9) | (5.4) | (5.5) | |

| Cap | 12.6 | 16.2 | 13.8 | 18.4 | 19.8 | 18.9 |

| (6.0) | (4.2) | (5.0) | (3.0) | (0.4) | (2.0) | |

Note: Average contributions depending on treatment and subjects’ type using data from period 1-10 (without punishment) and 11-20 (with punishment). Numbers in parentheses display standard deviations using group averages as the unit of observation.

In contrast, privileged groups of heterogeneous capabilities (gray squares) do much better in fostering and sustaining cooperation. While contributions start around the same level as in the other two treatments, they stay at a high level until a typical endgame effect sets in (ρ = −0.066, p = 1.000). On average, subjects in Cap contribute 13.8 tokens which is significantly more compared to 9.5 in Base (MWU-test, p = 0.029) and 9.6 in Val (MWU-test, p = 0.034). This leads to our first result:

Observation 1: Without the opportunity to punish, average contributions in Val are not higher compared to Base. In contrast, heterogeneity in Cap has a positive and stabilizing effect on voluntary contributions over time leading to significantly higher contributions compared to both Base and Val.

Hence, even though standard theory predicts that public goods provision should be the same in both types of privileged groups, it is obvious that the two different sources of heterogeneity generate different contribution behavior. To understand the driving forces behind this result, in the following, we have a closer look at the type-specific behavior in these two treatments as illustrated by the middle (Val) and left panel (Cap) of Figure 1.

In Val contributions strongly differ between both types. On average, l-types only contribute 33% of the amount of h-types. In Cap, in contrast, contribution behavior is much more similar. Here, l-types’ contributions reach on average 78% of the level of h-types.

When comparing the type-specific contribution behavior between treatments, we find contribution differences between both types of privileged groups to be mainly driven by l- rather than by h-types. While the latter contribute about the same amount in both treatments (Val: 15.9, Cap: 16.2; MWU-test, p = 0.984), l-types in Cap contribute about twice as much as in Val (12.6 vs. 6.4; MWU-test, p = 0.007). Compared to our baseline treatment this reveals an asymmetric effect of heterogeneity. While in the case of heterogeneous valuations increased contributions by h-types are accompanied by decreased contributions of l-types, when players differ in their capabilities this has a positive effect on both player type’s contributions. We summarize these findings in our second observation:

Observation 2: Contribution differences between l- and h-types are much more pronounced in Val than in Cap. The difference between the two types of privileged groups mainly arises from different contribution behavior of l-types.

These results suggest that the two types of heterogeneity elicit different incentives to reciprocate the other types’ contributions. To test for this possibility, we conduct regression analysis with an individual i’s level of contribution in period t as dependent variable. As independent variables we use the lagged contributions of the other group members from the previous period to analyze subjects’ willingness to (conditionally) cooperate. In addition, we include period dummies and control for the dependency of observations by clustering standard errors on a group level. The results from OLS regressions conducted separately for each treatment and type are reported in Table 5.11

Table 5.

OLS regressions: Contributions on others’ lagged contributions

| Dependent variable: ci, t | Base |

Val |

Cap |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contributions by i | l-types | h-types | l-types | h-types | |

| (Avg.) lagged contrib. l-types |

0.702*** (0.107) |

0.645*** (0.118) |

0.333* (0.161) |

0.473*** (0.111) |

0.487*** (0.185) |

| Lagged contrib. h-types |

0.075 (0.058) |

0.317** (0.081) |

|||

| Constant | 3.236*** (1.527) |

0.327 (1.898) |

14.900*** (2.199) |

3.157* (1.779) |

10.958*** (2.470) |

| Period dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| # Observations | 405 | 288 | 144 | 270 | 135 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.465 | 0.447 | 0.083 | 0.426 | 0.283 |

Note: OLS regressions with data from period 2-10. Robust standard errors (clustered on groups) in parentheses. *** Significance at p < 0.01, ** significance at p < 0.05, * significance at p < 0.1.

In homogeneous groups (Column 2) we find a strong and significant positive relationship between own contributions and the other group members’ contributions from the preceding period as predicted by conditional cooperation. This means that the higher (lower) the other group members’ contributions in the previous period, the higher (lower) are subject i′ s contributions in the subsequent period.

When looking at heterogeneous groups, in Val we observe an asymmetry in the willingness to reciprocate between types. While h-players do take into account contribution behavior of l-players (as indicated by a positive and significant coefficient), the latter seem to condition their contributions on the other l-player’s but not on the h-players’ behavior (as indicated by a small and insignificant coefficient of h-players’ lagged contributions). This means that l-players are at least to some extent willing to match each other’s contributions (maybe because of some form of social concern regarding the other l-player), but that they are reluctant to increase their contributions up to the level of the h-player. At the same time, however, h-players are willing to reciprocate l-players’ contributions. This is remarkable as contributing their entire endowment would not only maximize their material payoff, but also increases social efficiency leaving relative incomes unchanged. By withholding contributions, h-types may however follow an implicit punishment strategy which lowers each group members’ payoffs by the same amount.12

In Cap, in contrast, we find contribution behavior to be much closer and more symmetrically interrelated. H-players reciprocate contributions by l-players, and l-players reciprocate contributions by h- and other l-players (Columns 5 and 6). All these effects are positive and statistically significant. This implies that despite the fact of heterogeneous capabilities, the players’ incentives to match each other’s contributions are maintained. In this regard, our results extend the findings of Glöckner et al. (2011) who show that people are less inclined to cooperate if other’s contribution does not constitute a personal sacrifice. While this is indeed true in our Val-treatment, in Cap where all group members benefit equally from such contributions the willingness to reciprocate preserves.

In summary, our results indicate that the nature of asymmetry within a group crucially affects people’s willingness to cooperate. In particular, we find that groups of asymmetric capabilities are much better in coordinating on high cooperation levels than groups of asymmetric preferences. In the following, we analyze to what degree the results found so far hold or change when subjects are given the possibility to punish each other. This is interesting as previous studies have shown that heterogeneity can lead to an increased ambiguity and disagreement about the contribution norm which, in turn, can substantially affect the enforcement of cooperation through informal sanctions (cf. Reuben and Riedl, 2013). We investigate whether, and if yes, how this finding interacts with the different sources of heterogeneity in our experiment.

3.2. Voluntary Contributions with Punishment

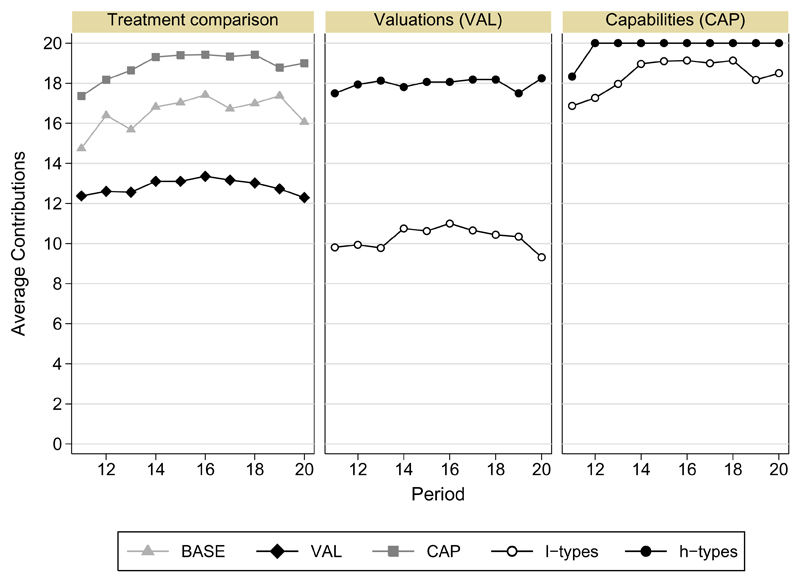

Figure 2 summarizes contribution behavior over time (periods 11-20) when punishment is possible. The left panel shows average contributions for all three treatments. The middle and right panel depicts contribution behavior separated by l- and h-types for the Val- and Cap-treatment, respectively.

Figure 2.

Average contributions over time when punishment is possible

Figure 2 shows several interesting observations. First, as indicated by the left panel, contributions in Cap are significantly higher than in the other two treatments (MWU-test, p < 0.025 for both comparisons). Second, contributions in Val now fall short even below the levels provided in Base (MWU-test, p = 0.053). Overall, average contributions in the three treatments amount to 18.9, 16.5, and 12.8 in Cap, Base, and Val, respectively. Third, while in Base and Cap contributions significantly increase over time (ρ = 0.348, p = 0.035 and ρ = 0.515, p < 0.001, respectively), in Val no such upward trend can be observed (ρ = 0.026, p = 0.210). One reason for the rather flat contribution dynamics in Val is that introducing punishment causes opposing reactions leading to an increased dispersion of contribution behavior between groups as indicated by an increased standard deviation of contributions compared to the no-punishment condition (see Table 4). In fact, in 5 out of 16 groups average contributions are lower than under the no-punishment condition. In the other two treatments, in contrast, punishment has a consistent positive effect in all groups leading to higher and less dispersed contributions.

In line with that, compared to the first ten periods, we find that the positive effect of punishment on contributions differs across treatments. As predicted, in the case of asymmetric valuations we find punishment to be less effective in enforcing cooperation within groups. Although contributions significantly increase in all three treatments compared to the no-punishment condition (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p < 0.030 for all comparisons), this effect is particularly strong when all subjects benefit equally from the public good. The average increase in contributions in Base and Cap is substantially larger than in Val (7.0, 5.1, and 3.3, respectively). A joint test of Base and Cap versus Val reveals the statistical significance of this difference (MWU-test, p = 0.054). We summarize this finding in our third observation:

Observation 3: The type of heterogeneity crucially affects the effectiveness of punishment in fostering cooperation. While privileged groups of asymmetric capabilities almost reach full contributions, in the case of asymmetric valuations punishment is much less effective in increasing contributions leading them to perform even worse than homogeneous groups.

To shed further light on this result, we now focus on the behavior of l- and h-types. As illustrated by the middle and right panel of Figure 2, we find pronounced differences between both types of privileged groups. While in Val contributions between both player types strongly diverge, in Cap they contribute very similar amounts (compare also Table 4). The difference between both types’ contributions amount to 7.7 and 1.4 tokens in Val and Cap, respectively (MWU-test, p = 0.009). When comparing the type-specific behavior across treatments, similar to the first ten periods, we find the main difference between both kinds of privileged groups originating from disparities in the l-types’ rather than the h-types’ behavior. While the latter contribute similar amounts in both treatments (MWU-test, p = 0.382), l-types in Cap contribute nearly twice as much as in Val (MWU-test, p = 0.002).

To summarize, when introducing the possibility to punish, privileged groups of asymmetric valuations lose their privileged status completely and perform even worse than homogeneous groups. Yet, as can be seen from the results in Cap, it is not the asymmetric nature of groups per se that but rather the specific type of heterogeneity that hampers cooperation. To understand the driving forces that cause the strong differences in contribution behavior between treatments, we now analyze to what extent they depend on the way group members punish each other.

3.3. Punishment Behavior

The average amount of punishment points spent is similar across treatments (Base: 1.3; Val: 0.6; Cap: 0.7). Although subjects in homogeneous groups punish slightly more than in privileged groups, these differences are not statistically significant (Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.330). Also pairwise comparisons of allocated and received punishment within and between treatments and types do not reveal any statistically significant differences. Yet, there might still be systematic differences in the way subjects punish each other conditional on their contributions.

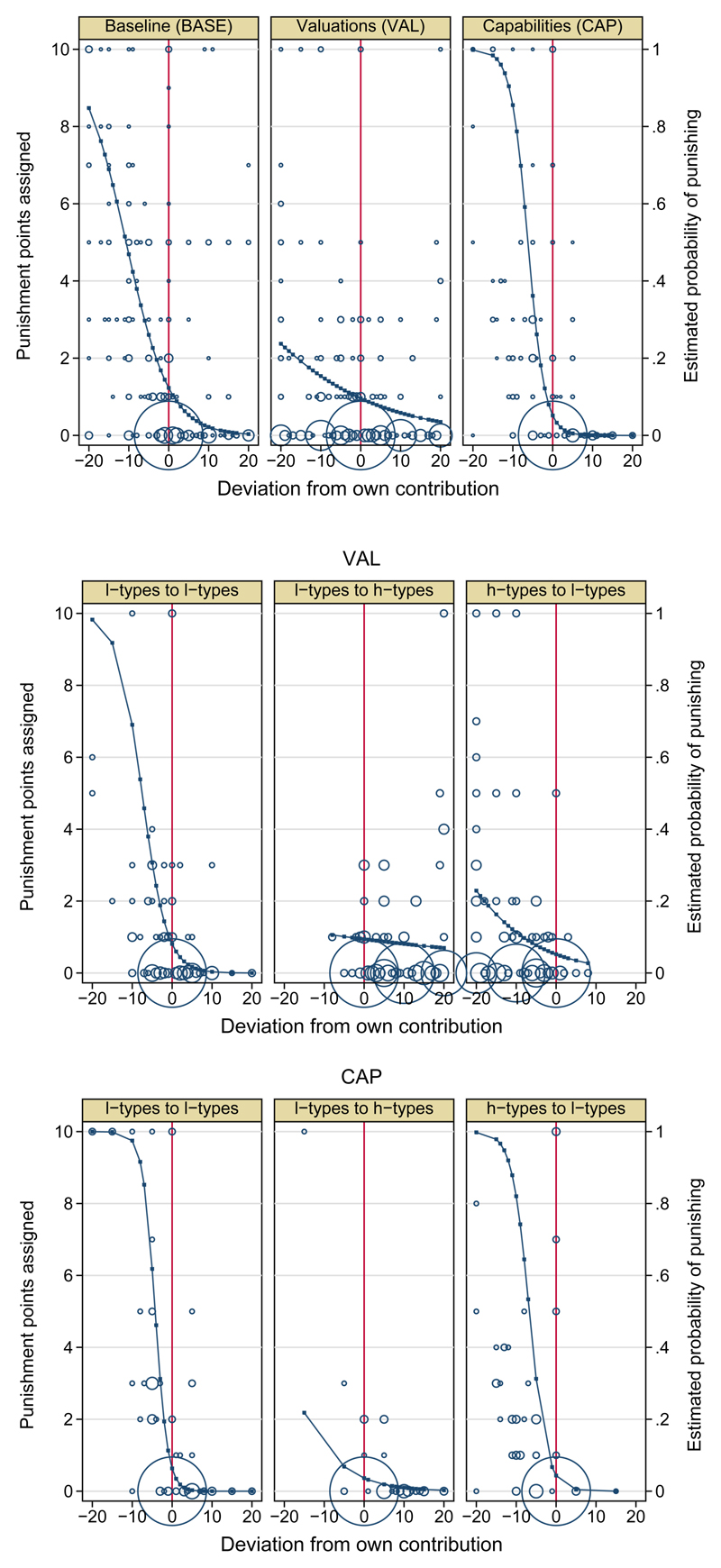

To check for this possibility, separated for each treatment, the upper panel of Figure 3 depicts the number of punishment points subjects assign as a function of the deviation from the own contribution. The size of each circle represents the relative frequencies of a given tuple. The solid line indicates the predicted values from a logistic regression with a dummy variable for assigning punishment as the dependent variable and the deviation from the punisher’s contribution as independent variable.

Figure 3.

Assigned punishment as a function of deviation from punisher’s contribution

The picture clearly shows that punishment patterns are considerably different across treatments. While in Base and Cap negative deviations are frequently and severely punished, in Val we observe a much less systematic punishment pattern. In particular, negative deviations often get away unpunished as indicated by the much flatter slope of the punishment function. In fact, negative deviations from a group member’s contribution are being punished in 57%, 22%, and 73% of the cases in Base, Val, and Cap, respectively, implying that especially in Val low contributions are considered more tolerable. Furthermore, in contrast to the other two treatments in Val we observe a much higher degree of punishment directed towards high contributing group members. This leads to our fourth observation:

Observation 4: Punishment behavior systematically differs between both types of privileged groups. While the absolute amount of punishment is very similar across treatments, in Cap negative deviations from own contributions are much more systematic and much severely punished compared to Val.

To further understand the differences in punishment behavior between Val and Cap, the middle and lower panel of Figure 3 differentiates these effects between each possible combinations of punisher’s and punishee’s type. The picture clearly shows that the differences between both types of privileged groups are mainly driven by the way how l-players punish h-players and vice versa. While punishment of l-players among each other is quite similar across the two treatments, h-players in Val punish negative deviations from their own contribution to a much lower extent than their counterparts in Cap. At the same time, l-players in Val frequently punish h-players even if they contribute more than themselves. In Cap such “antisocial punishment” is only very rarely observed.

These results are further supported by regression analysis. Table 6 reports results from OLS regressions using the amount of punishment points subject i dealt out to subject j, pij, as the dependent variable, and the deviation of j’s contribution from the other two group members’ contribution, i and k, as independent variables. For punishment directed towards h-players we additionally include a dummy taking the value 1 if h-players contribute fully and 0 otherwise. Our specification allows for different slopes for social and antisocial punishment and further controls for different time trends, level effects, and the dependency of observations within groups.13

Table 6.

OLS regressions: Punishment assigned to j by i

| Dependent variable: pij |

l-types to l-types |

l-types to h-types |

h-types |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Punishment given by i to j | Base | Val | Cap | Val | Cap | Val | Cap |

| Positive deviation from ci max (cj – ci, 0) | 0.042** (0.018) |

0.010 (0.011) |

0.021 (0.034) |

0.035* (0.018) |

-0.003 (0.010) |

0.042*** (0.014) |

0.025 (0.018) |

| Negative deviation from ci max (ci – cj, 0) | 0.208** (0.074) |

0.213*** (0.062) |

0.576*** (0.076) |

0.066** (0.030) |

0.543*** (0.104) |

0.012 (0.013) |

0.162*** (0.009) |

| Positive deviation from ck max (cj – ck, 0) | 0.003 (0.016) |

-0.036 (0.031) |

-0.029 (0.029) |

-0.036 (0.021) |

-0.022 (0.017) |

0.021 (0.012) |

-0.037* (0.017) |

| Negative deviation from ck max (cj – ck, 0) | 0.073 (0.095) |

-0.012 (0.012) |

-0.035 (0.021) |

-0.003 (0.030) |

-0.059 (0.046) |

0.259** (0.090) |

0.030 (0.060) |

| Full contribution 1 if cj = 20, 0 otherwise | -0.190* (0.097) |

-0.283 (0.290) |

|||||

| Constant | 0.842 (0.521) |

0.300 (0.332) |

0.099 (0.507) |

0.479 (0.313) |

-0.090 (0.133) |

-0.325 (0.420) |

0.202 (0.370) |

| Time trend | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| # Observations | 900 | 320 | 300 | 320 | 300 | 320 | 300 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.344 | 0.228 | 0.597 | 0.031 | 0.686 | 0.326 | 0.314 |

Note: OLS regressions with data from period 11-20. To account for different time trends we include period as a continuous variable as well as a dummy for the last period. Robust standard errors (clustered on groups) in parentheses.*** Significance at p < 0.01, ** Significance at p < 0.05, * Significance at p < 0.1.

Columns 2-4 present the results of how l-types punish other l-types. For all treatments we observe that negative deviations from their own contributions are strongly and significantly punished, and that relative deviations from the third group member k do not significantly affect punishment behavior. When comparing the strength of the punishment across treatments, we find that it is more pronounced in Cap than in Val and Base (Wald test, p < 0.01 for both comparisons) but that there is no significant difference between the latter two (Wald test, p = 0.961).

In line with the visual impression from Figure 3, we also find differences in the way l-types punish h-types between both types of privileged groups. In Val (Column 5) we find that deviations from the own and the third group member’s contribution matter only little (yet significantly) for punishment behavior, but that instead the biggest effect comes from whether h-types contribute fully or not. In Cap (Column 6), in contrast, punishment of l-types towards h-types strongly depends on deviations from own contributions and is very similar compared to punishment towards other l-types. Overall, as indicated by the very low R-squared in Val compared to Cap, the punishment pattern of l-types directed towards h-types seems to be generally less dependent on relative contributions.

Turning to the punishment behavior of h-types (Columns 7-8) in Val we observe that deviations from own contributions are not punished, but that negative deviations from the third group member’s contributions are strongly and significantly punished. In Cap, in contrast, we find that mainly negative deviations from own contributions matter for punishment behavior. In addition, there is a small “punishment discount” for not being the lowest contributor in the group. This result implies that while in Cap h-types try to enforce a norm of equal nominal contributions punishing everyone who free-rides on their contributions, in Val h-types seem to only punish the lowest contributor of the group tolerating that they contribute less than themselves.

One possible explanation for the different punishment behavior of h-players is that in Val there is no inequality motive for punishment as h-players never earn less than their group members, irrespective of their contributions. In addition, h-players might refrain from punishment when they expect l-players to be reluctant to increase their contributions even if getting punished as this would increase inequality to their disadvantage. Similarly, the differences in l-players’ punishment towards high contributors can be explained by the incentives in Val to punish h-players to reduce payoff inequality, even if the latter contribute more. In Cap, in contrast, such behavior is not necessary as h-types are only better off when they contribute less than their group members, which is almost never the case.

In summary, we conclude that it is not the total amount of punishment but rather the specific punishment patterns that can explain why the effectiveness of punishment in increasing contributions differs across both types of privileged groups. In particular, in the case of asymmetric preferences low contributions have a higher likelihood of being tolerated, suggesting that the norm of equal contributions is enforced less consequently.

3.4. Payoffs, Inequality, and Social Efficiency

As emphasized before, the main difference between both types of privileged groups are the different externalities contributions have on the other group members causing the payoff structure to be symmetric in Cap but asymmetric in Val. In the following, we investigate what consequences these treatment differences have on social efficiency as well as the distribution of wealth within groups. Table 7 summarizes average payoffs by treatment and players’ type as well as a measure for wealth inequality. Under the no-punishment condition, we find total payoffs in Cap to be significantly higher than in Val (43.1 vs. 34.3) reaching on average 86% and 69% of social efficiency (MWU-test, p = 0.002). Furthermore, lower efficiency in Val is accompanied by a higher degree of payoff inequality within groups. While in Cap both types of players earn very similar amounts, in Val h-players end up with much higher payoffs than their group members. To quantify this effect, we calculate the standard deviation of earnings within each group as a natural and simple measure of inequality.14 As expected, inequality is much more pronounced when there is heterogeneity in valuations rather than in capabilities (11.4 vs. 4.3, MWU-test, p = 0.016). We summarize this in the following result:

Observation 5: Under the no-punishment condition, groups of asymmetric capabilities achieve higher social efficiency and lower inequality compared to groups of asymmetric valuations.

Table 7.

Average payoffs by treatment and type, and inequality within groups

| Without Punishment |

With Punishment |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payoffs | Inequality | Payoffs | Inequality | |||||

| l-player | h-player | total | l-player | h-player | total | |||

| Base | 24.8 | - | 24.8 | 4.0 | 23.4 | - | 23.4 | 2.5 |

| (2.3) | - | (2.3) | (1.6) | (5.3) | - | (5.3) | (2.4) | |

| Val | 28.0 | 47.1 | 34.3 | 11.4 | 26.6 | 58.0 | 37.0 | 18.6 |

| (2.2) | (16.4) | (6.2) | (9.1) | (3.7) | (22.0) | (8.3) | (11.9) | |

| Cap | 44.3 | 40.7 | 43.1 | 4.3 | 46.1 | 46.9 | 46.4 | 1.7 |

| (6.2) | (7.5) | (6.4) | (2.3) | (3.5) | (4.4) | (3.6) | (1.7) | |

Note: Average payoffs depending on treatment and subjects’ type using data from period 1-10 (without punishment) and 11-20 (with punishment). Inequality is measured as the average standard deviation of payoffs within groups. Numbers in parentheses display standard deviations using group averages as the unit of observation.

While punishment has proven to be effective in increasing cooperation (cf. Fehr and Gächter, 2002), the question whether it is also beneficial in terms of payoffs depends on its cost effectiveness and the time horizon of interaction (see Chaudhuri, 2011, for a discussion). In our experiment, we find that the implementation of punishment leads to a small but insignificant decrease in average payoffs in Base (-1.4 points, WSR-test, p = 0.755), a moderate but insignificant increase in Val (2.7 points, WSR-test, p = 0.121), and a large and significant increase in Cap (3.3 points, WSR-test, p = 0.011). On average, efficiency in Base, Val, and Cap now reaches 78%, 74%, and 93%, respectively, of the social optimum. As under the no-punishment condition, the difference between both types of privileged groups is highly significant (MWU-test, p = 0.002). Besides that, punishment also affects the distribution of wealth within groups. Compared to the no-punishment condition, in Val inequality significantly increases when punishment is introduced (11.4 vs. 18.6, WSR-test, p = 0.034). In Base and Cap, in contrast, punishment significantly decreases inequality compared to the no-punishment condition (Base: 4.0 vs. 2.5, WSR-test, p = 0.020; Cap: 4.3 vs. 1.7, WSR-test, p < 0.001). This leads to our sixth result:

Observation 6: In Base and Val punishment has no significant effect on social efficiency. While in the former it leads to a significant decrease in inequality, in the latter it significantly increases payoff inequality within groups. When group members differ in their capabilities (Cap), however, punishment significantly increases social efficiency and significantly decreases inequality.

4. Conclusion

In this article, we investigate the effect of two sources of heterogeneity - valuations and capabilities - on the provision of public goods. We compare these two types of heterogeneity in two different conditions, one in which group members can punish each other and one in which peer punishment is not possible. Under both conditions, we find that the nature of group heterogeneity crucially influences cooperation and coordination within groups. Compared to homogeneous groups, we find that asymmetric valuations have no or, in the case of punishment, even detrimental effects on voluntary contributions. In contrast, asymmetric capabilities have positive and stabilizing effects on contribution behavior under both conditions. In addition, the type of heterogeneity also affects the usage and effectiveness of informal sanctions. In the case of capability heterogeneity negative deviations from own contributions are commonly and severely punished leading to less inequality and increased efficiency. When group members differ in their valuations, in contrast, negative deviations are punished less systematically and less severely. Furthermore, in this treatment punishment does not enhance social efficiency but increases payoff inequality within groups.

The main reason for our results are the different externalities contributions have on the other group members’ payoffs causing the payoff structure to be asymmetric in one case and symmetric in the other. If people are not only concerned by maximizing their own monetary payoff but also exhibit some form of other-regarding preferences, this can affect the principle of reciprocity and cooperation in non-trivial ways. In particular, if group members benefit equally from the public good (like in Cap) and have a preference for equal outcomes, they have an incentive to match each other’s contributions which, in turn, can facilitate the agreement and establishment of a contribution norm that fosters cooperation and coordination. When individuals benefit differently from the public good (like in Val), in contrast, preferences for equal outcomes can decrease an individual’s willingness to match the other group members’ contributions which, in turn, can have detrimental effects on the level cooperation. In our experiment we find evidence for both of these effects suggesting equality concerns as one potential explanation for our treatment differences between the two types of heterogeneity.

With regard to Olson’s (1965) theory on privileged groups, we find that, depending on the nature of their privilege, they do or do not fulfill their privileged status. Our results further imply an extension of the findings of Glöckner et al. (2011) showing that individuals are willing to reciprocate contributions even if they do not constitute a sacrifice, but only if all group members benefit equally from such contributions. All in all, we provide evidence that it is not the asymmetric nature of groups per se that facilitates or impedes collective action, but that it is the specific type of heterogeneity determining the degree of cooperative behavior and the level of public good provision.

Our results highlight the importance of investigating the effects of diversity within societies on collective action problems. We provide evidence that abstracting from heterogeneity in social dilemma situations can be a serious shortcoming, as inequality among group members can have opposing effects on cooperation. Because in everyday-life heterogeneous group environments are the rule rather than the exception, understanding the driving forces of cooperation in these groups is of great importance. In line with previous research (Heckathorn, 1993; Varughese and Ostrom, 2001; Poteete and Ostrom, 2004; Reuben and Riedl, 2009; 2013) our findings stress the importance of a proper understanding of the context dependent interplay of heterogeneity, institutions, social norms, and collective action. In related contexts, other studies already have emphasized the relevance of community heterogeneity on e.g. social capital (Alesina and La Ferrara, 2000), civic engagement (La Ferrara, 2002; Costa and Kahn, 2003), or the maintenance of irrigation systems (Bardhan and Dayton-Johnson, 2002).

Insights from this research can have important policy implications, for instance by assisting organizations and policy-makers in developing institutions that effectively alleviate cooperation and coordination failure in social dilemma situations. For example, in a firm context our results suggest that the formation of teams in which members have different interests in the success of a joint project, or paying different team-performance related bonuses to otherwise identical agents may have detrimental effects on the group output. Furthermore, while relying on informal sanctions to foster cooperation has shown to be ineffective in the case of asymmetric valuations, when individuals differ in their capabilities they seem to work quite well in encouraging collective action. One important challenge for future research is to test and develop institutions and incentive mechanisms that help to effectively alleviate the cooperation problem that is particularly strong when group members differ in their interest of group success.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Dirk Sliwka, Bernd Irlenbusch, Daniele Nosenzo, seminar participants at the University of Nottingham and the University of Cologne, participants at the Economic Science Association Meeting in Chicago, and particularly Simon Gächter for helpful comments and suggestions. I additionally thank the Centre for Decision Research and Experimental Economics (CeDEx) for the hospitality during a research stay in 2011/12. Financial support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through grant ’TP3 Design of Incentive Schemes within Firms: Bonus Systems and Performance Evaluations’ (sub-project of the DFG-Forschergruppe ’Design and Behavior’, FOR 1371), the European Research Council Advanced Investigator Grant Project COOPERATION (ERC-Adg 295707), and from the Network of Integrated Behavioural Science (NIBS) funded by the ESRC (ES/K002201/1) are gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

For example, the implementation of fishing quotas might be seen as individually optimal or not, depending on how much a country’s economy depend on fishing. Likewise, in the case of the fight against international terrorism, depending on the likelihood of being a target, countries may perceive the benefits of contributing as being larger or lower than the costs (compare Reuben and Riedl, 2009). Furthermore, more generally, also groups in non-linear public good environments with interior Nash equilibria can be regarded as being privileged even though their contributions would still typically fall short the social optimal level.

To our knowledge, the only experimental studies that analyze the interaction of heterogeneity and punishment are Burns and Visser (2006), Reuben and Riedl (2009; 2013), and Noussair and Tan (2011). While the first study finds positive effects of punishment on cooperation, the latter find that punishment is relatively ineffective in increasing contributions in heterogeneous environments. Relatedly, Nikiforakis et al. (2010) investigate heterogeneity in players’ effectiveness of punishment. They find that asymmetric punishment institutions are as effective as symmetric institutions in sustaining cooperation.

Experiments investigating the effects of wealth heterogeneity in social dilemmas report mixed results. While most studies find that endowment inequality leads to lower contributions (Ostrom et al., 1994; Cherry et al., 2005; Anderson et al., 2008), a few studies report neutral or even positive effects (Chan et al., 1996; 1999; Buckley and Croson, 2006).

Several studies investigate the effects of different material incentives to contribute. Without altering the Nash prediction of full free-riding, Isaac et al. (1984) and Isaac and Walker (1988) find that higher marginal benefits from the public good also lead to higher contributions (see Zelmer (2003) for an overview). While these studies implement heterogeneity only between groups, other studies analyze the effects of within-group inequality by manipulating the opportunity costs of contributing (Fisher et al., 1995; Palfrey and Prisbrey, 1996; 1997; Goeree et al., 2002).

In each period, subjects in each treatment receive an additional lump sum payment of five tokens. These tokens, however, do not alter contribution possibilities to the public good. This was done because of some additional treatments unrelated to the research question in this paper. As the lump-sum payment does not alter any of our predictions and results, we discard it from our analysis.

In this study, we abstain from controlling for order effects as we are mainly interested in treatment differences. Moreover, as has been shown previously (cf. Fehr and Gächter, 2000), the sequence of play, i.e., whether the punishment condition is played first or last, does not affect the effectiveness of punishment. In the results section we therefore interpret changes in behavior as a response to the introduction of punishment rather than other explanations such as experience or learning effects.

When comparing the efficiency of contributions between both types of privileged groups, it becomes apparent that while contributions made by h-types are more efficient in Cap, contributions made by l-types are more efficient in Val. In particular, in Cap and Val an h-players’ contribution increases social efficiency by 3 · 1.5 − 1 = 3.5 and 1.5 + 2 · 0.5 − 1 = 1.5 tokens, respectively. In contrast, an l-players’ contribution increases social efficiency by 3 · 0.5 − 1 = 0.5 and 1.5 + 2 · 0.5 − 1 = 1.5 tokens in Cap and Val, respectively.

See Kölle et al. (2011) for a theoretical analysis of capability heterogeneity on public goods provision when agents are inequity averse.

Intention-based theories of social preferences may also lead to different predictions across treatments. While in homogeneous groups, low and high contributions may have an unambiguous interpretation of being kind or unkind, in privileged groups this judgment is more difficult. For example, in these groups contributions of h-players cannot unequivocally be identified as being a nice act as they also maximize their individual payoffs. As a consequence, l-players might be unsure whether to reciprocate these contributions or not which, in turn, might hamper cooperation (Glöckner et al., 2011). While this is true in both types of privileged groups, contributions of h-players might also be evaluated more kindly in Cap than in Val. The reason is that due to the different externalities, by contributing h-types in Cap have to fear the risk of being worse off which is not the case for their counterparts in Val. Likewise, free riding of l-players might be judged being more unkind in Cap than in Val, as in contrast to the latter, in the former this also gives them a monetary advantage in relative terms.

Throughout this paper, when using Spearman’s rank-order correlation we calculate a correlation coefficient using groups as the unit of independent observation and report the average. For the p-value we apply a Binomial test with the null hypothesis that a positive and a negative trend are equally likely. Furthermore, if not otherwise indicated, we use a non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test (henceforth MWU-test) for comparisons between treatments and a non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test (henceforth WSR-test) for within-treatment comparisons. We always apply two-sided test statistics and use group averages based on data from all relevant periods (either 1-10 or 11-20) as the unit of observation.

We also conducted Tobit regression and random effects regressions. Since all the results are very similar, for the ease of presentation we decided to only report the ones from OLS.

Such behavior is in line with results from previous experiments studying explicit one-to-one punishment mechanisms finding that even when punishment does not affect relative incomes, subjects punish each other although this is not very effective in increasing contributions (Egas and Riedl, 2008; Nikiforakis and Normann, 2008; Sutter et al., 2010).

We also applied Tobit regressions to account for the fact that punishment exhibits censoring from above and below. Since the results are very similar, for the ease of presentation we decided to only report the ones from OLS.

Using alternative measures such as the coefficient of variation or the distance between the highest and lowest payoff leads to very similar results.

References

- Alesina A, La Ferrara E. Participation in heterogeneous communities. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2000;115(3):847–904. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson L, Mellor J, Milyo J. Inequality and public good provision: An experimental analysis. Journal of Socio-Economics. 2008;37(3):1010–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Andreoni J. Why free ride? strategies and learning in public goods experiments. Journal of Public Economics. 1988;37(3):291–304. [Google Scholar]

- Bardhan P, Dayton-Johnson J. Unequal irrigators: Heterogeneity and commons management in large-scale multivariate research. In: Ostrom E, Dietz T, Dolsak N, Stern P, Stonich S, Weber E, editors. The Drama of the Commons. National Academy Press; 2002. pp. 87–112. [Google Scholar]

- Benkler Y. Coase’s penguin, or, linux and ”the nature of the firm”. Yale Law Journal. 2002;112(3):369–446. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton GE, Ockenfels A. ERC - A theory of equity, reciprocity and competition. American Economic Review. 2000;100(1):166–93. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley E, Croson R. Income and wealth heterogeneity in the voluntary provision of linear public goods. Journal of Public Economics. 2006;90(4):935–955. [Google Scholar]

- Burns J, Visser M. Bridging the great divide in south africa: Inequality and punishment in the provision of public goods. Working Paper. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Chan K, Mestelman S, Moir R, Muller R. The voluntary provision of public goods under varying income distributions. Canadian Journal of Economics. 1996;29(1):54–69. [Google Scholar]

- Chan K, Mestelman S, Moir R, Muller R. Heterogeneity and the voluntary provision of public goods. Experimental Economics. 1999;2(1):5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Charness G, Rabin M. Understanding Social Preferences with Simple Tests. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2002;117(3):817–869. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri A. Sustaining cooperation in laboratory public goods experiments: a selective survey of the literature. Experimental Economics. 2011;14(1):47–83. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. Incentive-compatible mechanisms for pure public goods: A survey of experimental research. Handbook of Experimental Economics Results. 2008;1:625–643. [Google Scholar]

- Cherry T, Kroll S, Shogren J. The impact of endowment heterogeneity and origin on public good contributions: evidence from the lab. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 2005;57(3):357–365. [Google Scholar]

- Costa D, Kahn M. Civic engagement and community heterogeneity: An economist’s perspective. Perspective on Politics. 2003;1(1):103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Croson R. Partners and strangers revisited. Economics Letters. 1996;53(1):25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dufwenberg M, Kirchsteiger G. A theory of sequential reciprocity. Games and Economic Behavior. 2004;47(2):268–298. [Google Scholar]

- Egas M, Riedl A. The economics of altruistic punishment and the maintenance of cooperation. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2008;275(1637):871–989. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk A, Fischbacher U. A theory of reciprocity. Games and Economic Behavior. 2006;54(2):293–315. [Google Scholar]

- Fehr E, Gächter S. Cooperation and punishment in public goods experiments. American Economic Review. 2000;90(4):980–994. [Google Scholar]

- Fehr E, Gächter S. Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature. 2002;415(6868):137–140. doi: 10.1038/415137a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr E, Schmidt K. A Theory of Fairness, Competition, and Cooperation. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1999;114(3):817–868. [Google Scholar]

- Fehr E, Schmidt KM. The economics of fairness, reciprocity and altruism - experimental evidence and new theories. In: Kolm S, Ythier JM, editors. Handbook of the Economics of Giving, Altruism, and Reciprocity. Vol. 1. Elsevier; 2006. pp. 615–691. [Google Scholar]

- Fellner G, Iida Y, Kröger S, Seki E. Heterogeneous productivity in voluntary public good provision: An experimental analysis. IZA Discussion Paper. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Fischbacher U. Z-tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics. 2007;10(2):171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J, Isaac R, Schatzberg J, Walker J. Heterogenous demand for public goods: Behavior in the voluntary contributions mechanism. Public Choice. 1995;85(3):249–266. [Google Scholar]

- Gächter S, Herrmann B. Reciprocity, culture and human cooperation: previous insights and a new cross-cultural experiment. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2009;364(1518):791–806. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glöckner A, Irlenbusch B, Kube S, Nicklisch A, Normann H. Leading with (out) sacrifice? a public-goods experiment with a privileged player. Economic Inquiry. 2011;49(2):591–597. [Google Scholar]

- Goeree J, Holt C, Laury S. Private costs and public benefits: unraveling the effects of altruism and noisy behavior. Journal of Public Economics. 2002;83(2):255–276. [Google Scholar]

- Greiner B. An online recruitment system for economic experiments. Forschung und Wissenschaftliches Rechnen. 2004;63:79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin G. Tragedy of the commons. Science. 1968;162:1243–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn D. Collective action and group heterogeneity: voluntary provision versus selective incentives. American Sociological Review. 1993;58(3):329–350. [Google Scholar]

- Isaac R, Walker J. Group size effects in public goods provision: The voluntary contributions mechanism. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1988;103(1):179–199. [Google Scholar]

- Isaac R, Walker J, Thomas S. Divergent evidence on free riding: An experimental examination of possible explanations. Public Choice. 1984;43(2):113–149. [Google Scholar]

- Kölle F, Sliwka D, Zhou N. Inequality, inequity aversion, and the provision of public goods. IZA Discussion Paper. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- La Ferrara E. Inequality and group participation: theory and evidence from rural tanzania. Journal of Public Economics. 2002;85(2):235–273. [Google Scholar]

- Ledyard JO. Public goods: A survey of experimental research. In: Kagel JH, Roth AE, editors. The Handbook of Experimental Economics. Princeton University Press; 1995. pp. 111–194. [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforakis N, Normann H. A comparative statics analysis of punishment in public-good experiments. Experimental Economics. 2008;11(4):358–369. [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforakis N, Normann H-T, Wallace B. Asymmetric enforcement of cooperation in a social dilemma. Southern Economic Journal. 2010;76(3):638–659. [Google Scholar]

- Noussair C, Tan F. Voting on punishment systems within a heterogeneous group. Journal of Public Economic Theory. 2011;13(5):661–693. [Google Scholar]

- Olson M. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Harvard University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom E, Gardner R, Walker J. Rules, Games, and Common-Pool Resources. University of Michigan Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Palfrey T, Prisbrey J. Altruism, reputation and noise in linear public goods experiments. Journal of Public Economics. 1996;61(3):409–427. [Google Scholar]

- Palfrey T, Prisbrey J. Anomalous behavior in public goods experiments: How much and why? American Economic Review. 1997;87(5):829–46. [Google Scholar]

- Poteete A, Ostrom E. Heterogeneity, group size and collective action: The role of institutions in forest management. Development and Change. 2004;35(3):435–461. [Google Scholar]

- Rabin M. Incorporating fairness into game theory and economics. American Economic Review. 1993;83(5):1281–1302. [Google Scholar]

- Reuben E, Riedl A. Public goods provision and sanctioning in privileged groups. Journal of Conflict Resolution. 2009;53(1):72–93. [Google Scholar]

- Reuben E, Riedl A. Enforcement of contribution norms in public good games with heterogeneous populations. Games and Economic Behavior. 2013;77(1):122–137. [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson P. The pure theory of public expenditure. Review of Economics and Statistics. 1954;36(4):387–389. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel J. Interdependent preferences and reciprocity. Journal of Economic Literature. 2005;43(2):392–436. [Google Scholar]

- Sutter M, Haigner S, Kocher M. Choosing the carrot or the stick? endogenous institutional choice in social dilemma situations. Review of Economic Studies. 2010;77(4):1540–1566. [Google Scholar]

- Varughese G, Ostrom E. The contested role of heterogeneity in collective action: Some evidence from community forestry in nepal. World Development. 2001;29(5):747–765. [Google Scholar]

- Zelmer J. Linear public goods experiments: A meta-analysis. Experimental Economics. 2003;6(3):299–310. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.