Abstract

Background

Influenza vaccination is recommended especially for persons at risk of complications. In 2003, the World Health Assembly urged Member States (MS) to increase vaccination coverage to 75% among older persons by 2010.

Objective

To assess progress towards the 2010 vaccination goal and describe seasonal influenza vaccination recommendations in the World Health Organization (WHO) European Region.

Methods

Data on seasonal influenza vaccine recommendations, dose distribution, and target group coverage were obtained from two sources: European Union and European Economic Area MS data were extracted from influenza vaccination surveys covering seven seasons (2008/2009–2014/2015) published by the Vaccine European New Integrated Collaboration Effort and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. For the remaining WHO European MS, a separate survey on policies and uptake for all seasons (2008/2009–2014/2015) was distributed to national immunization programmes in 2015.

Results

Data was available from 49 of 53 MS. All but two had a national influenza vaccination policy. High-income countries distributed considerably higher number of vaccines per capita (median; 139.2 per 1000 population) compared to lower-middle-income countries (median; 6.1 per 1000 population). Most countries recommended vaccination for older persons, individuals with chronic disease, healthcare workers, and pregnant women. Children were included in < 50% of national policies. Only one country reached 75% coverage in older persons (2014/2015), while a number of countries reported declining vaccination uptake. Coverage of target groups was overall low, but with large variations between countries. Vaccination coverage was not monitored for several groups.

Conclusions

Despite policy recommendations, influenza vaccination uptake remains suboptimal. Low levels of vaccination is not only a missed opportunity for preventing influenza in vulnerable groups, but could negatively affect pandemic preparedness. Improved understanding of barriers to influenza vaccination is needed to increase uptake and reverse negative trends. Furthermore, implementation of vaccination coverage monitoring is critical for assessing performance and impact of the programmes.

Keywords: Influenza vaccines, Immunization programmes, Vaccination coverage

1. Background

Seasonal influenza is an acute viral infection that occurs worldwide causing an estimated 3–5 million severe cases and up to 500 000 deaths every year [1]. Annual influenza epidemics in the northern hemisphere have been associated with increases in all-cause mortality [2], [3], significant economic costs due to lost workforce productivity and increased demand on outpatient and inpatient health care services [4], [5], [6], [7], [8].

Influenza infection usually has a mild course, but can lead to severe disease and complications including acute myocardial infarction and cardiovascular death, primary viral and secondary bacterial pneumonia, renal failure, and neurological complications [9], [10], [11]. Particularly older people, pregnant women, infants, and persons with certain underlying comorbidities, including chronic cardiovascular and lung diseases, immunosuppression, and diabetes have a higher risk of hospitalization and severe disease, and are consequently priority groups for influenza vaccination [12]. Health care workers are also recommended to receive annual influenza vaccination due to a higher risk of infection and potential role in transmission of influenza to vulnerable patient groups [13], [14], [15].

Influenza vaccination remains the most effective means to prevent infection, severe disease and mortality, why increasing seasonal influenza vaccine coverage has long been on the global health agenda. In 2003, the World Health Assembly (resolution WHA 56.19) urged member states to increase influenza vaccination coverage of all people at high risk and to attain a coverage of ≥75% among older people and persons with chronic illnesses by 2010 [16]. This motion was reaffirmed by a European Parliament declaration in 2005, calling on European Union (EU) and European Economic Area (EEA) member states to increase influenza vaccination in accordance with the WHO’s 2010 goal, and extended in a 2009 European Council recommendation to reach 75% vaccination coverage in older age groups by 2015 [17]. Furthermore, the Global Action Plan (GAP) for influenza vaccines was launched by WHO in 2006 with the overarching goal to increase global influenza vaccine production and develop capacity to effectively deliver and administer vaccines in the event of a pandemic through an increased use of seasonal influenza vaccines, in particular in low- and middle income countries [18]. Since the adoption of GAP, global production capacity for seasonal vaccines has increased substantially; from 500 million to 1.5 billion doses in 2015, while the potential for producing pandemic influenza vaccines has increased from 1.5 to 6.4 billion doses in the same time period [19]. Although the GAP project formally ended in 2016, WHO’s work to increase access to influenza vaccines in low resource countries is continuing under the Pandemic Influenza Preparedness (PIP) Framework that was endorsed in 2011 [20].

In the WHO European Region, which consists of 53 member states (Fig. 1), data on seasonal influenza vaccine use, recommendations and coverage is limited outside of the EU/EEA member states, where surveys have been conducted regularly beginning from the 2007/2008 influenza season [21]. In order to describe seasonal influenza immunization policies and to assess progress towards improved access to and use of seasonal influenza vaccines in the entire WHO European Region, we implemented a survey among countries outside of the EU/EEA and conducted an analysis of the combined data for the European Region covering the period 2008/2009 to 2014/2015.

Fig. 1.

Map showing member states of the WHO European Region. AL: Albania, AD: Andorra, AM: Armenia, AT: Austria, AZ: Azerbaijan, BY: Belarus, BE: Belgium, BA: Bosnia and Herzegovina, BG: Bulgaria, HR: Croatia, CY: Cyprus, CZ: Czech Republic, DK: Denmark, EE: Estonia, FI: Finland, FR: France, GE: Georgia, DE: Germany, GR: Greece, HU: Hungary, IS: Iceland, IE: Ireland, IL: Israel, IT: Italy, KZ: Kazakhstan, KG: Kyrgyzstan, LV: Latvia, LT: Lithuania, LU: Luxembourg, MT: Malta, MC: Monaco, ME: Montenegro, NL: Netherlands, NO: Norway, PL: Poland, PT: Portugal, MD: Republic of Moldova, RO: Romania, RU: Russian Federation, SM: San Marino, RS: Serbia, SK: Slovakia, SI: Slovenia, ES: Spain, SE: Sweden, CH: Switzerland, TJ: Tajikistan, MK: The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, TR: Turkey, TM: Turkmenistan, UA: Ukraine, GB: United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and UZ: Uzbekistan. Note: The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate borderlines for which there may not yet be full agreement.

2. Methods

Information on seasonal influenza vaccine recommendations, number of doses distributed and estimates of vaccination coverage by target group was obtained through two different mechanisms. First, data from 29 countries of the EU/EEA was extracted from survey reports published by the Vaccine European New Integrated Collaboration Effort (VENICE) consortium and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) [22], [23], [24]. The annual EU/EEA surveys were conducted using the same methodology. For each survey, a standard questionnaire was developed, piloted and placed on a secure website platform and national experts in each country were requested to complete the on-line questionnaire. The surveys included detailed questions on population groups recommended for influenza vaccination; mechanisms in place to monitor influenza vaccine uptake, including methodology; vaccination coverage by population groups; number of vaccine doses distributed; payment and administration costs for influenza vaccines; health care settings where vaccination is typically provided; communication strategies to promote influenza vaccines; and information on planned policy or operational changes with regard to the national influenza immunization programme. Vaccination coverage was reported by the member states as proportions (data on numerator and denominator were not collected). Throughout the period surveyed, most countries used administrative methods (e.g. patient records or immunization registries) while some countries implemented population surveys (e.g. household, mail, or telephone) to obtain coverage data for certain target groups. A detailed description of the VENICE methodology has been published in the individual survey reports [22], [23], [24].

Second, in September 2015, the WHO Regional Office for Europe implemented a survey in the remaining 21 WHO European Region member states outside of the EU/EEA, including Croatia, which joined the EU in 2013, covering seven influenza seasons (2008/2009 to 2014/2015). Data were not requested from Andorra, Monaco, and San Marino. The survey (available in English and Russian) was distributed by email to the focal points for the national immunization programme under the Ministries of Health and included questions on: Quantity of seasonal influenza vaccine doses distributed; existence of national recommendations for vaccination of older people, children, pregnant women (including specification of whether this recommendation applied to certain trimesters and/or of presence underlying chronic illness), persons with chronic illness, residents of long-term care facilities (LTCF), health care workers, and non-health care occupational groups; and estimates of vaccination coverage by target group (including data on number of persons vaccinated and number of persons in target group). Information on which specific chronic medical conditions were included in the national recommendations was not requested in this survey.

Data from the different surveys (EU/EEA and non-EU/EEA) were combined into one dataset using Excel 2007 (Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, WA, USA) as of May 2017 for all member states of the WHO European Region for seven influenza seasons (2008/2009 to 2014/2015). Data for EU/EEA countries were based on data published at that time. Since data on influenza vaccine recommendations were not collected for the EU/EEA countries in the 2008/2009 season,1 we used information from the 2007/2008 season [25] as a proxy for vaccination policies in 2008/2009 for these countries.

In addition, we obtained information on country total mid-year population and income category (low, lower-middle, upper-middle and high) based on GNI per capita in US$ for the same period from the United Nations, Population Division (2015) [26] and the World Bank [27], respectively. This information was added to the dataset in order to calculate dose per capita in relation to country economic status.

Descriptive data analysis was performed using Tableau 9.2 (WA, USA) and STATA version 10.0 (StataCorp; College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

Of the 50 countries surveyed, 49 provided data for at least one influenza season. Survey responses were provided for all seven years by 45 member states, although data on all variables were not always provided. Responses were not received for the following countries and years: Austria (2011/2012 and 2012/2013), Bosnia and Herzegovina (2008/2009–2014/2015), Finland (2010/2011), and Luxembourg (2013/2014 and 2014/2015). Information on influenza vaccination policies was not available for Bulgaria and Luxembourg in 2008/2009 and for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (United Kingdom) in 2009/2010.

3.1. National influenza vaccination policies and vaccine doses available

All but two member states (Azerbaijan and Tajikistan) had a national seasonal influenza vaccination programme in the time period surveyed, although Armenia, Georgia, and the Republic of Moldova did not distribute influenza vaccines in some of the seasons (ranging from one to three seasons).

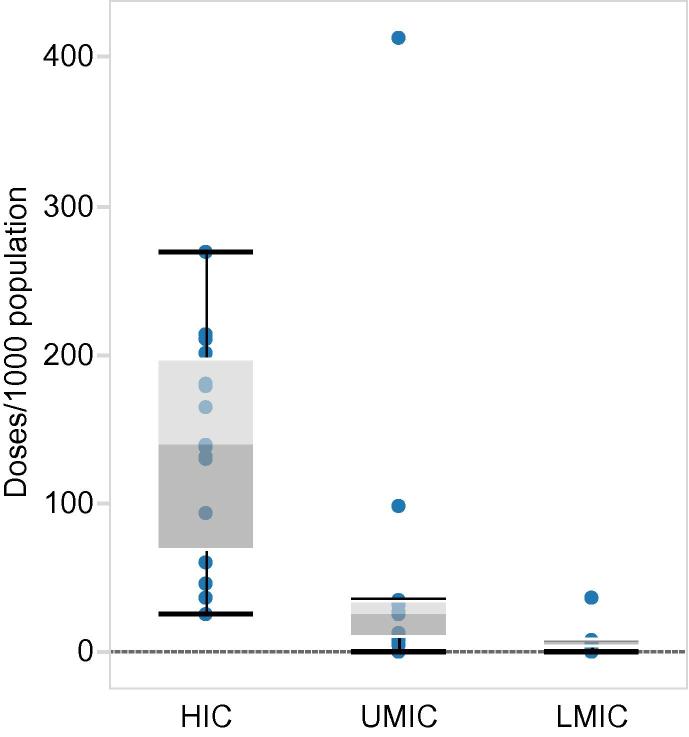

Forty-five member states provided information on the number of influenza vaccine doses distributed for at least one year. The number of vaccine doses available in member states of the WHO European Region in the last season surveyed (2014/2015) varied considerably; from 0 to 413.3 per 1000 population (n = 36). High income countries (n = 18) distributed a considerably higher number of influenza vaccines doses (median; 139.2 per 1000 population) compared to upper-middle (n = 11) and lower-middle (n = 7) income countries which distributed a median of 25.6 and 6.1 doses per 1000 population respectively in 2014/2015 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Seasonal influenza vaccine doses distributed in 2014/2015 according to country income status: HIC = high income countries, UMIC = upper middle income countries, LMIC = lower middle income countries (income categories according to The World Bank [27]).

The number of vaccine doses distributed in the Region in 2008/2009, compared to 2014/2015, increased from 60 to 68 million doses (data based on countries for which information was available for both seasons; n = 31). This net regional increase was mainly due to increases in five countries; the Russian Federation (10.8 million), Belarus (3.2 million), Kazakhstan (1.2 million), Israel (0.8 million), and Portugal (0.5 million). Half of the countries reported a decline in number of doses distributed (ranging from 5000 to 2.7 million) in the seven year period representing a total of 8.7 million doses.

3.2. Influenza vaccine recommendations and vaccination coverage

3.2.1. Older people

Among responding countries with a national vaccination policy in 2014/2015 (n = 46), all but one country, Armenia, recommended influenza vaccination for older people. Most of the countries (76%) recommended vaccination for persons ≥65 years of age, while a smaller proportion of countries also recommended vaccination for other age-groups: Persons ≥ 60 years (11%); ≥59 years (2%); ≥55 years (2%); and ≥50 years (9%) (2014/2015 data, n = 45).

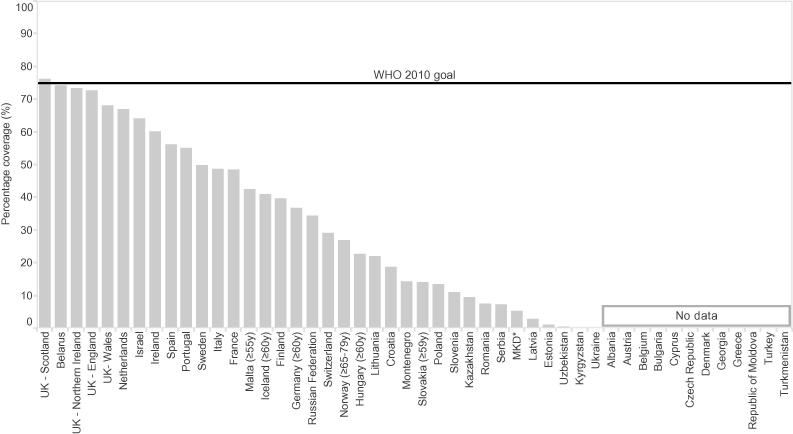

Information on coverage was provided by 33 (72%) of the countries recommending influenza vaccination for older people in 2014/2015. Vaccination uptake ranged from 0.03% to 76.3%, with a median of 34.4%. Only Scotland (United Kingdom) reached the WHO and European Council goal in the 2014/2015 season, although Belarus, and England and Northern Ireland (United Kingdom) were close (Fig. 3). The Netherlands was the only country in the Region that had met the goal by 2010, reporting coverage rates above 75% between the seasons 2008/2009 and 2011/2012, after which uptake dropped (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Influenza vaccination coverage among older people (≥65 years of age, unless otherwise indicated) in member states of the WHO European Region during the 2014/2015 season. *The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. Note: Data for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (UK) are shown separately for England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

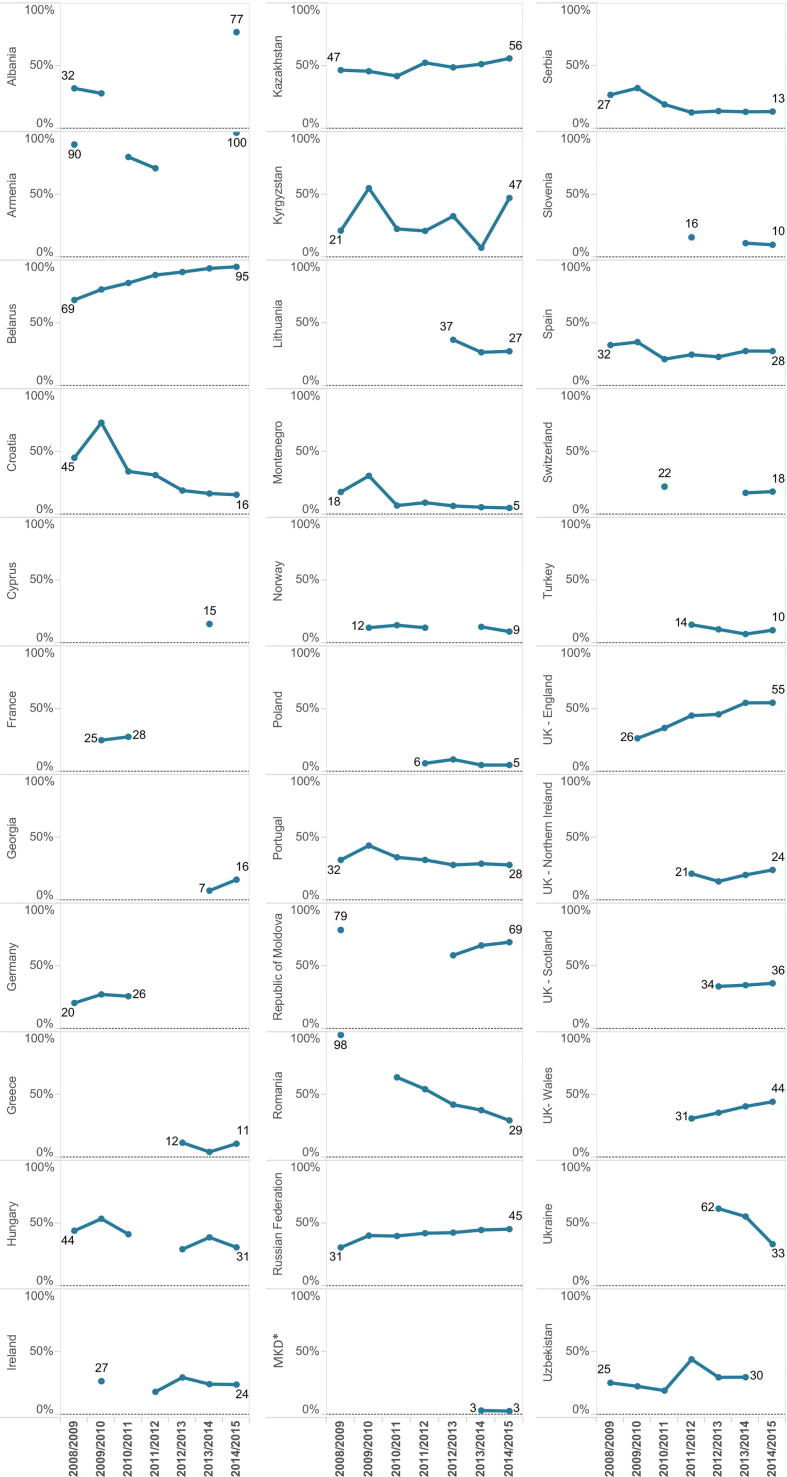

Fig. 4.

Trends in influenza vaccination coverage (%) among older people by country between 2008/2009 and 2014/2015. Only countries with ≥ 4 years of data included (n = 33). Note: Data for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (UK) are shown separately for England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales; France 2009/2010 data estimated through a survey (data for other years measured by administrative methods); Germany 2008/2009-2010/2011 data estimated through surveys and 2012/2013-2014/2015 data measured by administrative methods, 2008/2009-2009/2010 data show coverage for persons ≥65 years, while data for the following years show coverage for persons ≥60 years; Hungary data shows coverage for persons ≥60 years in 2008/2009-2011/2012 and 2014/2015, other years for persons ≥65 years; Malta data shown for persons ≥65 years in 2008/2009 and 2010/2011 and for persons ≥55 years in 2012/2013-2014/2015; Netherlands coverage data shown for person ≥60 years (2009/2010-2010/2011 and 2012/2013) and for persons ≥65 years (2011/2012 and 2013/2014-2014/2015); Norway 2008/2009-2009/2010 data measured by administrative methods, other years through surveys. Estimates for 2008/2009-2009/2010 include all persons at risk, coverage data for 2013/2014-2014/2015 are for persons ≥65–79 years. Portugal 2008/2009 coverage measured by administrative methods, 2010/2011-2011/2012 through surveys, and 2012/2013-2014/2015 through a combination of the two methods; Sweden coverage data (2008/2009-2011/2012) measured by administrative methods, 2012/2013 data estimated by a combination of administrative and survey methods and 2013/2014-2014/2015 data estimated by surveys, 2009/2010 data incomplete.

Decreasing trends in coverage could be observed in several other countries since 2008/2009 (Fig. 4). Among countries for which data on influenza vaccination coverage was available for both 2008/2009 and 2014/2015 (n = 26), over half (n = 15) reported a decline among older people. Romania reported the largest decrease in coverage from 49.4% in 2008/2009 to 7.4% in 2014/2015. The only country where uptake increased considerably was Belarus (from 5% in 2008/2009 to 74.2% in 2014/2015). Iceland, Israel, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal and the Russian Federation also reported increases in vaccination uptake among older persons, although marginal in some of the countries.

3.2.2. Children

Less than half of the member states (21 among 46) had influenza vaccination recommendations for children in 2014/2015. Countries recommending vaccination against influenza for children were mainly in the Eastern part of the region (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Member states in the WHO European Region with influenza vaccine recommendations for children in the 2014/2015 season. Note: The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate borderlines for which there may not yet be full agreement.

Of the 21 member states with a recommendation in 2014/2015, 20 provided information on the age groups targeted. Age groups recommended for influenza vaccination varied; however, most countries had recommendations for all children with some differences in the lower and upper age limit (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Influenza vaccine recommendations for children in the WHO European Region, 2014-2015 season. Note: Data for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (UK) are shown separately for England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

Coverage data was reported by 13 (62%) of the 21 member states with an influenza vaccination policy for children in 2014/2015, of which ten countries reported vaccination coverage for two separate age-groups. Coverage rates in children in the 2014/2015 season ranged from <1% in a number of countries to almost 80% in Northern Ireland (United Kingdom). The median coverage was 10.9%.

3.2.3. Chronic illnesses

Annual vaccination of persons with chronic diseases was generally recommended throughout the seven-year period by all member states with an influenza vaccination policy, except Turkmenistan, which had no specific recommendation. In two countries, Armenia and Uzbekistan, vaccine recommendations for persons with chronic diseases were not included in the seasonal influenza immunization programme in three (2009/2010, 2012/2013 and 2013/2014) and one (2013/2014) season(s) respectively.

In general, countries (data only available for EU/EEA member states) recommended annual influenza vaccination for persons with pulmonary, renal, hepatic, neurologic, and immunosuppressive diseases (including HIV/AIDS). For other chronic disease risk groups; including cardio-vascular disease, diabetes, morbid obesity, persons on long term aspirin use, vaccine recommendations differed by country.

Among the 44 countries with influenza vaccine recommendations for persons with specific chronic illnesses in 2014/2015, 14 (32%) provided information on coverage; most countries reported rates below 40%. Vaccination coverage in this target group ranged from 0.3% in Kyrgyzstan to 86.8% in Georgia. Only four member states (Belarus, Israel, Kazakhstan and the Netherlands) provided data for all seven years. In two of these countries; Belarus and Kazakhstan, vaccination coverage had increased considerably since 2008/2009; from 48.1% to 80.5% and from 18.4% to 72.0% respectively.

3.2.4. Pregnant women

Forty-two (91%) member states recommended influenza vaccination to pregnant women in 2014/2015 (n = 46) a considerable increase compared to 2008/2009, when 40% had recommendations for this risk group (n = 45) (Fig. 7). Furthermore, since 2008/2009, member states have increasingly recommended vaccination for all pregnant women regardless of trimester and presence of underlying illnesses. Four countries (Bulgaria, Malta, Montenegro and Slovakia) did not have national recommendations for maternal influenza vaccination.

Fig. 7.

Vaccine recommendations for pregnant women in the WHO European Region in 2008/2009 and 2014/2015. All: Recommended for all pregnant women irrespective of trimester and presence of underlying illness (details on specific groups recommended for vaccination not available for EU/EEA countries in 2007/2008); only chronic illness: Recommended for pregnant women with underlying chronic illness; certain trimesters: Recommended for pregnant women in 2nd and/or 3rd trimester only; none: No recommendation for pregnant women; no national policy: No national seasonal influenza vaccination programme. Information shown for Denmark, Germany and Norway for 2014/2015 is for healthy pregnant women; pregnant women with chronic medical conditions were recommended vaccination during all trimesters. Note: The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate borderlines for which there may not yet be full agreement.

Eleven (26%) of the 42 member states recommending influenza vaccination for pregnant women in 2014/2015 reported data on coverage. Vaccination coverage varied considerably, from <1% in four countries (Armenia, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Lithuania and Ukraine) to 86.5% in Kazakhstan (among pregnant women in second and third trimester) (median; 8.7%).

3.2.5. Long term care facilities

The majority of countries (89%) recommended seasonal influenza vaccination for persons living at long term care facilities (LTCFs) in 2014/2015 (n = 45). Albania, Denmark, Latvia, the Russian Federation, and Sweden did not have recommendations for this group in 2014/2015. Finland and Poland added residents of LTCFs to their national influenza immunization programme in 2011/2012 and 2010/2011 respectively. Of the 40 countries with recommendations, 11 (28%) reported data on vaccination coverage in 2014/2015. Coverage was overall high in most of the years with a median of 77% (range 16.1% to 96.6%) in 2014/2015.

3.2.6. Health care workers

All member states with an influenza immunization policy, except one (Denmark), had national recommendations for vaccination of health care workers against influenza in 2014/2015 (n = 46). During the seven year period, two countries had revised their national recommendations to include health care workers (Finland and Sweden). Twenty-six countries (56%) reported data on coverage in 2014/2015 (n = 46), an increase from 16 countries (33%) in 2008/2009 (n = 45). There was a large variation in vaccination uptake in this group, ranging from 2.6% to 99.5%; median 29.5% (2014/2015 data) with few countries reporting a high uptake (>75%) (Albania, Armenia and Belarus). The majority of countries reported coverage rates <40% and in some countries there was an indication of decline, most notably in Romania and Croatia (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Trends in influenza vaccination coverage (%) among health care workers by country for seven influenza seasons in the WHO European Region. *The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. Note: Data for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (UK) are shown separately for England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales; Ireland coverage data for 2009/2010 and 2012/2013 estimated by surveys, while 2011/2012, 2013/2014 and 2014/2015 estimated by administrative methods; Portugal 2008/2009 coverage data incomplete.

3.2.7. Occupational groups (non-health care settings)

In 2014/2015, most countries (86%) reported having influenza vaccine recommendations in place for one or more occupational groups, including essential and emergency services (e.g. police, fire and rescue staff), military personnel, border control staff, farm and abattoir workers (poultry and/or swine), veterinary services, social workers, teachers, civil service employees, public transportation employees, airline crew members, and staff working in assisted living facilities, children’s homes and boarding schools (n = 42). This presented an increase from 2008/2009 when 60% recommended vaccination for specific occupational groups. Coverage data for these groups was not provided in the surveys.

4. Discussion

This paper provides the first comprehensive overview of seasonal influenza vaccine availability, policies and coverage in the WHO European Region from the year before the 2009 A(H1N1) pandemic until 2014/2015. The findings highlight major differences across countries regarding availability of seasonal influenza vaccine and coverage in target groups, changes in number of vaccine doses distributed over time in a number of countries, as well as substantial gaps in monitoring of vaccination uptake.

All but two countries in the European Region had national policy recommendations for seasonal influenza vaccination in 2014/2015. Despite an increase in the number of doses distributed in lower-middle income countries since 2008/2009, the quantity of vaccine doses procured remains low in this income group. Yet, in higher income countries there was also significant variability in number of vaccine doses distributed per capita.

Based on data from two-thirds of the member states the overall number of influenza vaccines distributed in the Region increased by 8 million doses between 2008/2009 and 2014/2015. However, this figure concealed large differences, with half of the countries reporting a steady decline in doses distributed. This finding is in keeping with reports by international influenza vaccine manufacturers of a decreasing production for the European market, where the number of vaccine doses distributed fell by 31.5% between 2008 and 2013 [28]. The overall increase in doses reported in this study was mainly due to a substantial increase in quantities of vaccines distributed in a few countries mainly in the Eastern part of the Region, including the Russian Federation, which has its own national production of influenza vaccines [29].

Annual influenza vaccination for older people, health care workers and persons with chronic diseases was almost universally recommended in the Region, and most countries also had recommendations for residents of LTCFs, and for occupational groups holding key functions in society or persons working in the animal sector, consistent with global recommendations [12], [30]. The number of countries with recommendations for pregnant women had increased considerably between 2008/2009 and 2014/2015. In most countries, the change in policy followed the emergence of the A(H1N1)pdm09 virus in 2009, which was shown to cause severe disease particularly among pregnant women [31]. Less than half of the countries, however, recommended vaccination for children. While countries with this policy generally included infants and young children, only five specifically targeted children 6–59 months old, a priority group among children due to a high disease burden [32]. Influenza vaccine recommendations for children of all ages were particularly widespread in the Eastern part of the Region, where school-closures aimed at controlling seasonal influenza outbreaks are common [33]. Vaccination of school-aged children, who experience high rates of influenza illness and play an important role in transmission of influenza in the community [34], [35], was also more recently introduced the United Kingdom as a strategy to reduce influenza disease in older individuals and other clinical risk groups [36].

Despite substantial evidence of severity of influenza among older people, who account for over 90% of deaths due to influenza [37], [38] and a long-standing commitment to increase coverage [16], [17], vaccination uptake in this risk group remains suboptimal and has even decreased in a number of countries. Only one member state in the Region achieved the goal of vaccinating ≥75% of older people in 2014/2015. With the exception of residents of LTCFs, a target group that may be relatively easy to reach, the limited data on vaccination rates among other clinical risk groups indicated a low uptake, but with large variations between countries. Many countries also reported poor influenza vaccination uptake among health care workers, which is concerning due to their increased risk of infection compared to non-health care employees and potential role in nosocomial transmission. Furthermore, health care providers that are not vaccinated themselves may be less likely to recommend vaccination to their patients [39].

Factors influencing vaccination uptake are complex, multidimensional and highly context specific [40], and can as such not be adequately explored in the type of surveys on which this analysis is based. Nonetheless, in lower-resourced countries in the European Region, low coverage is a result of limited vaccine procurement, suggesting that influenza is not considered a high priority disease. Lack of data on influenza morbidity and mortality, and their associated societal costs, in lower- and middle-income countries may be a contributing factor to this [41], [42]. In other countries of the WHO European Region, low and declining influenza vaccination uptake has been attributed to different factors including lack of confidence in the vaccine (effectiveness and safety), low perceived need for vaccination, lack of recommendation from health care providers, general decline in trust in public health institutions following the 2009 A(H1N1) pandemic, and out-of-pocket costs to receive vaccination [43], [44]. A recent publication reported that influenza vaccination is not provided free of charge to a number of key target groups in several EU/EEA member states [45]. In addition, delivering a national vaccination programme for influenza is challenging due to the diversity of the target groups, which fall outside the well-established childhood immunization programmes.

To effectively address vaccination gaps, it is necessary to understand the key barriers to vaccination at different levels of the health care delivery systems including at the individual, health care provider, and policy level. Recently developed tools, such as the Guide to Tailoring Immunization Programmes (TIP) and the ECDC online tool on influenza vaccination in health care workers, can assist national immunization programmes in analysing the demand and supply-side barriers and enablers for vaccination in order to design evidence-informed interventions to help increase vaccination uptake [46], [47]. Finally, producing country-specific estimates of the clinical and economic burden of influenza could provide important leverage to national influenza vaccination programmes through documenting the magnitude of the disease and its economic and societal impact.

In addition to low vaccine uptake, this report also revealed a substantial gap in data on vaccination coverage in the European Region. Efforts to increase vaccination uptake should be accompanied by establishing systems for monitoring vaccination coverage, which is a key indicator of programme performance, and essential for understanding gaps and trends in coverage and assessing the impact of the programme. Nonetheless, influenza vaccination is unique among immunization programmes due to a very heterogeneous target group, who may receive vaccination at different locations (e.g. outpatient clinics, pharmacies, long-term care facilities) and by different health care providers (e.g. paediatricians, obstetricians-gynaecologists, general practitioners), complicating record keeping. Furthermore, denominators for specific target populations, such as persons with chronic underlying diseases, may be difficult and costly to obtain [48].

Interpretation of influenza vaccination coverage data and vaccine doses presented in this report was limited by a number of factors: First, information on number of doses distributed and vaccination uptake was incomplete and available data may not accurately represent the situation in the WHO European Region. Nonetheless, information on number of distributed doses, available for a larger number of countries, did not suggest that vaccination coverage would be high in countries that did not report data on coverage. Second, we used the total population of each country to estimate access to vaccines per capita. Although a more accurate estimate could have been obtained using target group populations, this information was not available. Third, national vaccination coverage estimates may become available or be updated retrospectively after regional surveys have been completed which would not have been captured in this report. Finally, comparing risk group specific vaccination coverage rates between countries and within countries should be done with some caution as quality of vaccination data may differ and because countries have used different approaches to estimate coverage over time. Both administrative methods and surveys have limitations; the first may lead to inaccurate estimates of coverage if vaccination receipt is not consistently documented throughout the health care system or data on the denominator population are incorrect, while surveys can suffer from non-response and recall bias. However, specific details relating to national methods for calculating vaccination coverage was not available and it could not be assessed whether vaccination coverage rates were over- or underestimated. Moreover, a direct comparison of vaccination uptake for groups such as persons with underlying chronic conditions and health care workers may not be merited as countries include different sub-groups in their recommendations.

5. Conclusion

Despite widespread national policy recommendations on influenza vaccination, reaching high coverage rates continues to be a challenge in the European Region, as does availability of influenza vaccines in middle-income countries. Low and declining use of seasonal influenza vaccination not only presents a missed opportunity for preventing influenza in vulnerable population groups, but could negatively impact on the global production capacity for pandemic vaccines and on building country capacities for vaccine deployment in the event of a pandemic [19], [49]. An improved understanding of the barriers to vaccination, and the elimination of these, will be critical for increasing uptake and reversing negative trends. Development of national strategies on life-course immunization could be particularly valuable for promoting influenza vaccination due to the diverse patient- and age-groups recommended for vaccination. Nevertheless, since out-of-pocket expenses (even when reimbursable in full or partly) is a well-known barrier to vaccination [44], [50] and places a disproportionate financial burden on patients in lower income groups, provision of free of charge seasonal influenza vaccination to older people and other patient risk groups is an urgent task. A greater focus on improving vaccination coverage among health care workers is also warranted to reduce the risk of influenza infection among staff and their patients and to bolster health care provider’s role as vaccination advocates. For lower-resourced member states, global actions to increase access to affordable influenza vaccines should continue.

Disclaimer

The authors alone are responsible for the views presented in this manuscript and they do not necessarily reflect the views, decisions or policies of the institutions with which the authors are affiliated.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the WHO European Region national immunization and VENICE focal points for providing data on seasonal influenza vaccination used in this report.

Contributors

All authors contributed to the survey design; JM, SC, KJ and ST to the annual surveys implemented in EU/EEA countries, and PJ and CB to the survey carried out in remaining WHO European Region member states. PJ undertook the initial analysis of the data and wrote the first draft of the paper. JM, SC, KJ ST, and CB reviewed and contributed to writing the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The 2008/2009 seasonal influenza vaccine survey was replaced by a survey on A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccine deployment. Information on vaccination coverage only for the 2008/2009 season was collected as part of the 2009/2010 seasonal influenza vaccine survey.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Influenza (Seasonal). Fact sheet no. 211. Geneva, 2014. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs211/en/ [accessed 4 September 2017].

- 2.Mølbak K., Espenhain L., Nielsen J., Tersago K., Bossuyt N., Denissov G. Excess mortality among the elderly in European countries, December 2014 to February 2015. Euro Surveill. 2015:20. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2015.20.11.21065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vestergaard L.S., Nielsen J., Krause T.G., Espenhain L., Tersago K., Bustos Sierra N. Excess all-cause and influenza-attributable mortality in Europe, December 2016 to February 2017. Euro Surveill. 2017:22. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.14.30506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molinari N.M., Ortega-Sanchez I.R., Messonnier M.L., Thompson W.W., Wortley P.M., Weintraub E. The annual impact of seasonal influenza in the US: measuring disease burden and costs. Vaccine. 2007;25:5086–5096. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schanzer D.L., Zheng H., Gilmore J. Statistical estimates of absenteeism attributable to seasonal and pandemic influenza from the Canadian Labour Force Survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayward A.C., Fragaszy E.B., Bermingham A., Wang L., Copas A., Edmunds W.J. Comparative community burden and severity of seasonal and pandemic influenza: results of the Flu Watch cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:445–454. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70034-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paget W.J., Balderston C., Casas I., Donker G., Edelman L., Fleming D. Assessing the burden of paediatric influenza in Europe: the European Paediatric Influenza Analysis (EPIA) project. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169:997–1008. doi: 10.1007/s00431-010-1164-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baguelin M.J.M., Miller E., Edmunds W.J. Health and economic impact of the seasonal influenza vaccination programme in England. Vaccine. 2012;30:3459–3462. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Estabragh Z.R., Mamas M.A. The cardiovascular manifestations of influenza: a systematic review. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:2397–2403. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.01.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joseph C., Togawa Y., Shindo N. Bacterial and viral infections associated with influenza. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7(Suppl. 2):105–113. doi: 10.1111/irv.12089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rothberg M.B., Haessler S.D., Brown R.B. Complications of viral influenza. Am J Med. 2008;121:258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization Vaccines against influenza. WHO position paper - November 2012. Weekly Epidemiol Rec. 2012;47:461–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vanhems P., Voirin N., Roche S. Risk of influenza-like illness in an acute health care setting during community influenza epidemics in 2004–2005, 2005–2006, and 2006–2007: a prospective study. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:151–157. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuster S.P., Shah P.S., Coleman B.L., Lam P.P., Tong A., Wormsbecker A. Incidence of influenza in healthy adults and healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eibach D., Casalegno J.S., Bouscambert M., Bénet T., Regis C., Comte B. Routes of transmission during a nosocomial influenza A(H3N2) outbreak among geriatric patients and healthcare workers. J Hosp Infect. 2014;86:188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Prevention and control of influenza pandemics and annual epidemics. Geneva; 2003. http://www.who.int/immunization/sage/1_WHA56_19_Prevention_and_control_of_influenza_pandemics.pdf [accessed 7 September 2017].

- 17.Council of the European Union. Council Recommendation of 22 December 2009 on seasonal influenza vaccination. Brussels; 2009. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2009:348:0071:0072:EN:PDF [accessed 20 August 2017].

- 18.World Health Organization. Global vaccine action plan to increase vaccine supply. Geneva; 2006. http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/influenza/CDS_EPR_GIP_2006_1.pdf?ua=1 [accessed 5 September 2017].

- 19.McLean K.A., Goldin S., Nannei C., Sparrow E., Torelli G. The 2015 global production capacity of seasonal and pandemic influenza vaccine. Vaccine. 2016;34:5410–5413. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. Pandemic influenza preparedness framework for the sharing of influenza viruses and access to vaccines and other benefits. Geneva; 2011. http://apps.who.int/gb/pip/pdf_files/pandemic-influenza-preparedness-en.pdf [accessed 6 September 2017].

- 21.Mereckiene J., Cotter S., D'Ancona F., Giambi C., Nicoll A., Lévy-Bruhl D. Differences in national influenza vaccination policies across the European Union, Norway and Iceland 2008-2009. Euro Surveill. 2010;15(44) doi: 10.2807/ese.15.44.19700-en. pii:19700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Technical report. Seasonal influenza vaccination in Europe Overview of vaccination recommendations and coverage rates in the EU Member States for the 2012–13 influenza season. http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/Seasonal-influenza-vaccination-Europe-2012-13.pdf [accessed 5 September 2017].

- 23.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Technical report. Seasonal influenza vaccination and antiviral use in Europe. Overview of vaccination recommendations and coverage rates in the EU Member States for the 2013–14 and 2014–15 influenza seasons. http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/Seasonal-influenza-vaccination-antiviral-use-europe.pdf [accessed 5 September 2017].

- 24.European Commission. Comission staff working document. State of play on implementation of the Council Recommendation of 22 December 2009 on seasonal influenza vaccination (2009/1019/EU) http://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/vaccination/docs/seasonflu_staffwd2014_en.pdf [accessed 8 September 2017].

- 25.Vaccine European New Integrated Collaboration Effort (VENICE II Consortium). National Seasonal Influenza Vaccination Survey in Europe, 2007/2008 Influenza season. http://venice.cineca.org/Final_2009_Seasonal_Influenza_Vaccination_Survey_in_Europe_1.0.pdf [accessed 5 September 2017].

- 26.United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs PD. World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, DVD Edition. Secondary World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, DVD Edition 2015. https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/ [accessed 8 September 2017].

- 27.The World Bank. GNI per capita ranking, Atlas method https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD [accessed, 29 August 2017]. Secondary GNI per capita ranking, Atlas method https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD [accessed 29 August 2017].

- 28.Palache A., Oriol-Mathieu V., Fino M., Xydia-Charmanta M. Seasonal influenza vaccine dose distribution in 195 countries (2004–2013): little progress in estimated global vaccination coverage. Vaccine. 2015;33:5598–5605. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.08.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ministry of Health Care of the Russian Federation. Research Institute of Influenza. Influenza Vaccines. http://www.influenza.spb.ru/en/science_and_society/influenza_vaccines/ [accessed 28 August 2017].

- 30.World Health Organization Influenza vaccines. WHO position paper. Weekly Epidemiol Rec. 2005;33:279–287. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jamieson D.J., Honein M.A., Rasmussen S.A., Williams J.L., Swerdlow D.L., Biggerstaff M.S. H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection during pregnancy in the USA. The Lancet. 2009;374:451–458. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nair H., Brooks W.A., Katz M., Roca A., Berkley J.A., Madhi S.A. Global burden of respiratory infections due to seasonal influenza in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2011;378:1917–1930. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Resolution of the Chief State Sanitary Doctor of the Russian Federation of November 18, 2013 “On approval of sanitary-epidemiological rules 3.1.2.3117-13. Prevention of influenza and other acute respiratory viral infections” [in Russian].

- 34.Monto A.S., Sullivan K.M. Acute respiratory illness in the community. Frequency of illness and the agents involved. Epidemiol Infect. 1993;110:145–160. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800050779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reichert T.A., Sugaya N., Fedson D.S., Glezen W.P., Simonsen L., Tashiro M. The Japanese experience with vaccinating schoolchildren against influenza. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:889–896. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103223441204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hodgson D., Baguelin M., van Leeuwen E., Panovska-Griffiths J., Ramsay M., Pebody R. Effect of mass paediatric influenza vaccination on existing influenza vaccination programmes in England and Wales: a modelling and cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2:e74–e81. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(16)30044-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mertz D., Kim T.H., Johnstone J., Lam P.-P., Science M., Kuster S.P. Populations at risk for severe or complicated influenza illness: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;347 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson W.W., Shay D.K., Weintraub E., Brammer L., Cox N., Anderson L.J. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA. 2003;289:179–186. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paterson P., Meurice F., Stanberry L.R., Glismann S., Rosenthal S.L., Larson H.J. Vaccine hesitancy and healthcare providers. Vaccine. 2016;34:6700–6706. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Butler R., MacDonald N.E. Diagnosing the determinants of vaccine hesitancy in specific subgroups: the guide to Tailoring Immunization Programmes (TIP) Vaccine. 2015;33:4176–4179. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Francisco N., Donadel M., Jit M., Hutubessy R. A systematic review of the social and economic burden of influenza in low- and middle-income countries. Vaccine. 2015;33:6537–6544. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.10.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ott J.J., Klein Breteler J., Tam J.S., Hutubessy R.C.W., Jit M., de Boer M.R. Influenza vaccines in low and middle income countries. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9:1500–1511. doi: 10.4161/hv.24704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Determann D., de Bekker-Grob E.W., French J., Voeten H.A., Richardus J.H., Das E. Future pandemics and vaccination: public opinion and attitudes across three European countries. Vaccine. 2016;34:803–808. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kardas P., Zasowska A., Dec J., Stachurska M. Reasons for low influenza vaccination coverage: cross-sectional survey in Poland. Croat Med J. 2011;52:126–133. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2011.52.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mereckiene J., Cotter S., Nicoll A., Lopalco P., Noori T., Weber J.T. Seasonal influenza immunisation in Europe. Overview of recommendations and vaccination coverage for three seasons: pre-pandemic (2008/09), pandemic (2009/10) and post-pandemic (2010/11) Euro Surveill. 2014;19 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.16.20780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe. Tailoring Immunization Programmes. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/measles-and-rubella/activities/tailoring-immunization-programmes-to-reach-underserved-groups-the-tip-approach/the-tip-guide-and-related-publications [accessed 28 August 2017].

- 47.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Influenza vaccination of health care workers - can uptake be improved? ECDC Virtual Academy. https://eva.ecdc.europa.eu/mod/forum/discuss.php?d=400 [accessed 7 September 2017].

- 48.World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe. Methods for assessing influenza vaccination coverage in target groups http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/317344/Methods-assessing-influenza-vaccination-coverage-target-groups.pdf?ua=1 [accessed 11 September 2017].

- 49.Zhang W., Hirve S., Kieny M.-P. Seasonal vaccines – Critical path to pandemic influenza response. Vaccine. 2017;35:851–852. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.12.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Böhmer M.M., Walter D., Krause G., Müters S., Gößwald A., Wichmann O. Determinants of tetanus and seasonal influenza vaccine uptake in adults living in Germany. Human Vaccines. 2011;7:1317–1325. doi: 10.4161/hv.7.12.18130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]