Abstract

Background

Child sexual abuse is associated with a plethora of devastating repercussions. A significant number of sexually abused children are likely to experience other forms of maltreatment that can seriously affect their emotion regulation abilities and impede on their development. The aim of the study was to test emotion regulation and dissociation as mediators in the association between cumulative childhood trauma and internalized and externalized behavior problems in child victims of sexual abuse.

Methods

Participants were 309 sexually abused children (203 girls and 106 boys; Mean age = 9.07) and their non-offending parent. Medical and clinical files were coded for cumulative childhood trauma. At initial evaluation (T1), parents completed measures assessing children’s emotion regulation abilities and dissociation. At Time 2 (T2), parents completed a measure assessing children’s behavior problems. Mediation analyses were conducted with emotion regulation and dissociation as sequential mediators using Mplus software.

Results

Findings revealed that cumulative childhood trauma affects both internalized and externalized behavior problems through three mediation paths: emotion regulation alone, dissociation alone, and through a path combining emotion regulation and dissociation.

Limitations

Both emotion regulation and dissociation were assessed at T1 and thus the temporal sequencing of mediators remains to be ascertained through a longitudinal design. All measures were completed by the parents.

Conclusions

Clinicians should routinely screen for other childhood trauma in vulnerable clienteles. In order to tackle behavior problems, clinical interventions for sexually abused youth need to address emotion regulation competencies and dissociation.

Keywords: Sexual abuse, Child, Emotion regulation, Dissociation, Behavior problems

1. Introduction

Child sexual abuse (CSA) affects one out of five women and one out of ten men worldwide (Stoltenborgh et al., 2011). This highly prevalent social problem is associated with an array of long-term psychological, physical, and behavioral problems such as depression, suicidal ideations and attempts, substance dependence, posttraumatic stress disorder, sexual risk behaviors, and increased use of healthcare for physical health problems (Fergusson et al., 2013). While the last decades have seen major developments in research investigating long-term consequences of CSA among adults, studies of short-term correlates among children have been sparser, resulting in significant gaps in the scientific literature. Available studies indicate that sexually abused children are at higher risk of presenting a plethora of difficulties compared to non-abused children and even to children having sustained other forms of maltreatment (i.e., physical or emotional abuse, neglect), including behavior problems (Lewis et al., 2016; Maniglio, 2015), posttraumatic stress and dissociation symptoms (Hébert et al., 2016), as well as emotional dysregulation (Langevin et al., 2016; Shipman et al., 2000). Given the detrimental impacts of CSA on multiple aspects of child development, it is essential to further our understanding of the associated consequences of CSA with samples of children and explore the possible mechanisms linking CSA to negative outcomes.

1.1. Cumulative childhood trauma

Although CSA alone is sufficient to produce major dysfunctions, synergistic effects of cumulative childhood adversity – meaning that the interaction between two or more adverse experiences produces a greater combined effect than the sum of the individual effects – have been uncovered with adult samples in empirical studies (Putnam et al., 2013). Indeed, Putnam and colleagues found that the presence of four or more childhood adversities was associated with increased risk of presenting complex adult psychopathology. Furthermore, synergistic effects were found with specific combinations of trauma, several of which involved CSA (Putnam et al., 2013). Recently, a longitudinal study investigating adult functioning of survivors of childhood abuse and neglect found that exposure to a greater number of early adversities was associated with fewer years of education, higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms, and increased criminal arrests in adulthood (Horan and Widom, 2015). Number of trauma types also appears to be positively associated with dissociative symptoms in adults (Briere, 2006).

A study using a nationally representative sample of youth in the U.S. identified the occurrence of multiple trauma as a frequent phenomenon (Turner et al., 2015). According to this study, 21.3% of youth aged 10–17 years old have been victimized at school and at home, while 17.8% of them experienced polyvictimization (i.e., victimization occurring in multiple settings and involving multiple perpetrators). Polyvictimized children presented the worst outcomes in terms of delinquency and trauma symptom scores (Turner et al., 2015). Number of trauma types experienced was also associated with self-reported and caregiver-reported symptom complexity (i.e., clinical elevations in a variety of symptom clusters) in a clinical sample of school-aged children (Hodges et al., 2013). Finally, a study of sexually abused children found that cumulative childhood trauma was positively associated with emotional dysregulation and internalized and externalized behavior problems (Choi and Oh, 2014). Overall, studies tend to indicate that cumulative childhood trauma leads to more severe behavioral and psychological consequences than single experiences of trauma, both in adults and youth samples.

1.2. Emotion regulation and dissociation

Emotion regulation difficulties and dissociative symptoms have been documented as potential consequences associated with CSA and cumulative childhood trauma in children and adults. While the two concepts of emotion regulation and dissociation are often studied separately, there are conceptual and empirical associations between them. Some authors view dissociation as a regulatory strategy falling in the category of over-modulation or over-regulation of emotions (Bennett et al., 2015; Lanius et al., 2010), while others perceive it as the consequence of failed emotion regulation attempts (Kalill, 2013; Chaplo et al., 2015). Ford (2013) advocates for a vision of dissociation as a biologically based self-regulatory response to extreme emotions. He suggests that fostering self-regulation abilities is essential to the treatment of dissociation. Dissociation was also conceptualized as an avoidance strategy used to face emotions that overwhelm internal affect regulation capacities following a trauma (Briere et al., 2010). Therefore, while some scholars view dissociation as an emotion regulation strategy, more experts in the field tend to see it as a result of deficits in the ability to effectively self-regulate intense emotions. Thus, deficits in the area of emotion regulation are hypothesized to precede the occurrence of dissociation symptoms.

Consistent with this idea, empirical studies found that emotional dysregulation predicted dissociative symptomatology in trauma-exposed adults and sexually abused youth offenders (Briere, 2006; Chaplo et al., 2015; Powers et al., 2015). In a sample of maltreated teenagers, emotional dysregulation was found to predict dissociation symptoms over and beyond the forms of maltreatment experienced, the number of perpetrators involved, as well as the age of onset (Sundermann and DePrince, 2015). Another study with an adult sample found that affect dysregulation mediated the effect of cumulative interpersonal trauma on dysfunctional avoidance (i.e., dissociation, tension reduction behaviors, substance abuse, and suicidality) (Briere et al., 2010). In trauma-exposed youth offenders, higher levels of emotional dysregulation – including both over and under-regulation of emotional arousal – were found in individuals presenting high levels of dissociation, when compared to those presenting low levels of dissociation. In sum, coherent with theoretical models, a number of empirical reports indicate that emotional dysregulation might predict dissociation levels in traumatized adults and adolescents. However, no available study, that we are aware of, has investigated these associations in a sample of children.

1.3. Mediational analysis with emotion regulation and dissociation

To understand how variables are associated with each other, mediation and moderation analyses are indicated (Hayes, 2013). A number of past mediation and moderation studies investigated the patterns of associations among maltreatment, emotion regulation, and mental health outcomes. Eisenberg and Morris (2002) offered a conceptualization of self-regulation, including emotional self-regulation, involving three styles of control: overcontrol, undercontrol and optimal control. Overcontrolled children are thought to exert excessive control over their emotions and behaviors, and are therefore at-risk for developing internalizing problems. On the other hand, undercontrolled children tend to be less able to regulate themselves effortfully and are therefore at-risk for developing externalizing problems (Eisenberg et al., 2013). This conceptualization highlights the theoretical associations between emotion regulation and behavior problems.

Empirical findings tend to confirm this association. A study involving a sample of young adults found that emotional dysregulation mediated the association between high-betrayal trauma (i.e., abuse perpetrated by a close individual, as opposed to abuse perpetrated by a stranger or trauma that are not caused by another human being) and various mental health symptoms including anxiety, depression, intrusions, and avoidance (Goldsmith et al., 2013). Emotion regulation was also found to mediate the association between maltreatment and internalized and externalized behavior problems in school-age samples (Alink et al., 2009; Kim-Spoon et al., 2013). In one of these studies, the mediation effect was only found in insecurely attached children (Alink et al., 2009). In another study of school-age children, emotion regulation mediated the association between cumulative childhood trauma and internalized and externalized behavior problems in sexually abused children (Choi and Oh, 2014). Finally, a study indicated that, even in the preschool period, emotion regulation mediated the association between CSA and parental reports of child behavior problems (Langevin et al., 2015).

The association between dissociation and behavior problems has been less studied in maltreated children samples. However, a recent study showed that internalized behavior problems were associated with dissociation over and beyond the effects of maternal dissociation and depression/anxiety, number of traumatic events, and child gender in a sample of preschool children (Hagan et al., 2015). Kisiel and Lyons (2001) found that dissociation mediated the association between CSA and behavior problems in children aged 10–18 years old. Furthermore, dissociation was found to mediate the relationships between CSA and a number of mental health symptoms (i.e., depression, somatization, compulsive behavior, phobic symptoms, and borderline personality disorder) in a clinical sample of women (Ross-Gower et al., 1998). Berthelot et al. (2012) also found that dissociation mediated the association between CSA and internalized and externalized behavior problems in their sample of children aged 2–12 years old. They suggested that dissociation predicts the onset of behavior problems because it prevents the integration, resolution, and mentalization of the traumatic event. As a result, sexually abused children might be kept in a state of powerlessness and confusion favoring the emergence of behavioral difficulties (Berthelot et al., 2012). Overall, past studies tend to indicate that emotion regulation and dissociation symptoms explain, at least partially, the associations between traumatic events and mental health and behavioral problems in various samples of children and adults.

Against this backdrop, this study aims to further our understanding of CSA associated consequences in childhood by testing two mediation models investigating the relationships among cumulative childhood trauma, emotion regulation, dissociation, and internalized and externalized behavior problems in a sample of sexually abused school-aged children. Fig. 1 illustrates the hypothesized mediation model. Even though the two mediators were measured concurrently, we suggest a sequence where emotion regulation deficits precede dissociation symptoms based on previous theoretical and empirical works described earlier.

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized Mediation Model. Note. T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The sample consisted of 309 sexually abused children (203 girls, 106 boys) aged 6–12 years old (M = 9.07, SD = 2.17) and their non-offending parent (85.8% maternal figure, 9.6% father figure, 4.6% other known adult). Exclusion criteria were to not speak French or English and/or the presence of a developmental delay preventing from understanding the questionnaires. Children were recruited in five intervention centers offering services to abused children and their parents in the province of Quebec, Canada. T1 assessment was conducted in the intervention settings and T2 assessment (5 months later) was conducted at the centers or at the home of the participants. A total of 21.9% of children lived in their family of origin, the remaining lived in single-parent families (32.1%), stepfamilies (25.5%), or foster families (20.5%). Maternal education level corresponded to elementary school (2.8%), high school diploma (38.8%) or the equivalent of 12–14 years (41.3%), while 17.1% completed an undergraduate or graduate level. Close to half of families (52.3%) reported an annual income level of less than 40,000$ (CAN).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Cumulative childhood trauma

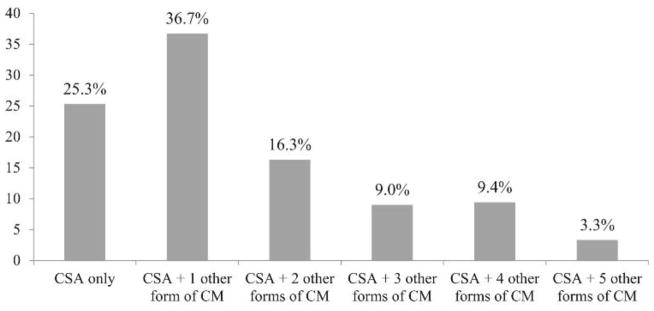

Data regarding children’s victimization history were gathered through various means in order to ensure a comprehensive assessment. Medical/clinical files were analyzed and data regarding past situations of CSA, physical abuse, psychological abuse, exposure to family violence, and neglect were coded using a modified version of the History of Victimization Form (HVF; Wolfe et al., 1987) and the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS; Kaufman et al., 1997). Data from the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus et al., 1996) completed by parents were also used to assess exposure to family violence. A continuous cumulative childhood trauma score ranging from 0 to 5 was derived from these data. Zero meant that, to our knowledge, the children only experienced the CSA event that brought him/her to the intervention center. Children with scores ranging from 1 to 5 had experienced 1–5 additional victimization experiences (i.e., another CSA situation, physical abuse, psychological abuse, neglect, and/or exposure to family violence). See Fig. 2 for detailed distribution.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of cumulative childhood trauma. Note. CM = Child maltreatment.

2.2.2. Emotion regulation

At T1, emotion regulation was assessed using parent reports on the 24-item Emotion Regulation Checklist (ERC; Shields and Cicchetti, 1997; French version: Langevin et al., 2010) a widely-used questionnaire known to discriminate between well-regulated and dysregulated children (Shields et al., 2001). The ERC measures emotional lability, intensity, flexibility, and situational appropriateness. Sample items include “is easily frustrated”, “is impulsive”, “is a cheerful child”, and “is able to delay gratification”. Parents were invited to rate their children’s behaviors in general with a Likert-scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (almost always). A total score of emotion regulation, ranging from 0 to 72, was calculated by reversing negatively weighted items and summing the scores on each item. A higher score reflects better emotion regulation competencies. In the present study, internal consistency for the total score was high (α = 0.84).

2.2.3. Dissociation

At T1, parents reported on the dissociation level of their children using the Child Dissociative Checklist (CDC; Putnam et al., 1993; French version: Hébert and Parent, 2000), a 20-item measure. The CDC is a well-renown measure of dissociation in children, and the reliability and validity of the scale was demonstrated by Putnam and his colleagues (1993). Sample items include “Child shows rapid changes in personality”, and “Child has difficult time learning from experience, e.g. explanations, normal discipline or punishment do not change his or her behavior”. Parents were invited to rate their children’s behavior on a three-point Likert-scale (0 = not true to 2 = very true). A total score ranging from 0 to 40 was obtained by summing scores on every item. In this study, internal consistency for the total score was adequate (α = 0.80).

2.2.4. Behavior problems

At T2, children’s behavior problems were assessed using parent reports on the Child Behavior Checklist – School-Age Version (CBCL; Achenbach and Rescorla, 2001). The CBCL is a widely-used 113-item measure of behavior problems from which two global subscales can be derived: internalized behavior problems (32 items) and externalized behavior problems (35 items). The internalized behavior subscale includes items related to anxiety/depression (13 items), social withdrawal/depression (8 items), and somatic complaints (11 items), while the externalized behavior subscale includes items related to antisocial behaviors (17 items) and aggression (18 items). Parents were invited to rate their children’s behaviors in the past two months on a three-point Likert-scale (0 = never true to 2 = often or always true). T-scores were derived from parents’ answers. Psychometric qualities of this questionnaire were demonstrated by Achenbach and Rescorla (2001). In this study, internal consistencies of the internalized behavior problems and externalized behavior problems subscales were high (α = 0.87 and 0.92 respectively).

2.3. Procedure

Children and their parents were recruited in five intervention centers in [BLIND FOR REVIEW]. Both parent and child informed written consent were obtained, and the questionnaires were completed at the intervention centers. A small financial compensation was offered to parents and a gift certificate to children. This research project was approved by the Ethics committees of the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire (CHU) Sainte-Justine and the Université du Québec à Montréal.

3. Results

3.1. Data analysis

In order to determine how cumulative childhood trauma affects internalized and externalized behavior problems, mediation analyses were conducted with emotion regulation and dissociation as sequential mediators using Mplus software, v.7.31. A multiple mediator model based on the product of coefficients approach was selected as an appropriate method to test the hypotheses (Preacher and Hayes, 2008). Bootstrapping method (Shrout and Bolger, 2002) was used for testing the significance of the total and the specific indirect effects. This technique has been advocated as preferable to causal steps approach (Baron and Kenny, 1986) for testing the indirect effects (MacKinnon et al., 2002, 2004; Preacher and Hayes, 2004). The principle of bootstrapping method consists of drawing a large number (10,000 in this study) of resamples with replacement, from the observed dataset, and then estimate the total and the specific indirect effects within each bootstrap sample. These estimates are in turn used to construct bias-corrected confidence intervals for the indirect effects. An indirect effect is said to be statistically significant when its corresponding bias-corrected confidence interval does not include zero. Missing data were treated with full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) implemented in Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, 2015).

3.2. Correlation between variables

Pearson’s correlations were performed using SPSS 22 in order to examine the strength of the association among study variables. Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations and correlations between the variables. Results revealed a significant, medium, negative correlation between emotion regulation and the two variables measuring behavior problems. Correlation between emotion regulation and dissociation was significant, negative, and high. Dissociation showed a high positive correlation with internalized behavior problems and a medium positive correlation with externalized behavior problems. The correlation between internalized and externalized behavior problems was significant, positive and high. Cumulative childhood trauma showed a significant, low, positive correlation with both dissociation and externalized behavior problems. Correlation between cumulative childhood trauma and emotion regulation was also significant and low, but negative. Results indicated a non-significant correlation between cumulative childhood trauma and internalized behavior problems and between age and all other study variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations among study variables.

| M | (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotion regulation | 46.88 | (10.08) | – | |||||

| Girls | 48.14 | (10.04) | ||||||

| Boys | 44.35 | (9.74) | ||||||

| 2. Dissociation | 7.55 | (5.67) | −0.57*** | |||||

| Girls | 7.69 | (5.94) | – | |||||

| Boys | 7.27 | (5.10) | ||||||

| 3. Internalized behavior problems | 56.28 | (11.07) | −0.36*** | 0.50*** | – | |||

| Girls | 56.49 | (11.23) | ||||||

| Boys | 55.89 | (10.84) | ||||||

| 4. Externalized behavior problems | 58.70 | (10.78) | −0.43*** | 0.46*** | 0.69*** | – | ||

| Girls | 58.32 | (10.72) | ||||||

| Boys | 59.41 | (10.94) | ||||||

| 5. Cumulative childhood trauma | 1.51 | (1.38) | −0.14* | 0.21** | 0.05 | 0.18** | – | |

| Girls | 1.52 | (1.41) | ||||||

| Boys | 1.47 | (1.32) | ||||||

| 6. Age (in months) | 114.10 | (25.89) | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.13 | 0.09 | – |

| Girls | 113.12 | (25.88) | ||||||

| Boys | 115.98 | (25.95) |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

3.3. Mediation analyses

The first mediation analysis explored the relationship between cumulative childhood trauma and internalized behavior problems in the presence of the two sequential mediators. As presented in Table 2, cumulative childhood trauma was significantly associated with both emotion regulation (β = −1.10, p < 0.05) and dissociation (β = 0.51, p < 0.05), but not with internalized behavior problems when controlled for the mediators (β = −0.55, p = 0.26). Emotion regulation and dissociation were both related with internalized behavior problems (β = −0.14, p < 0.05 and β = 0.86, p < 0.001, respectively). The results also showed that emotion regulation was significantly associated with dissociation (β = −0.31, p < 0.001). These results suggest that cumulative childhood trauma has an indirect effect on internalized behavior problems through its association with emotion regulation and dissociation.

Table 2.

Estimation of the multiple mediator models.

| Predictor variables | Predicted variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | 95% CI | β | SE | 95% CI | |

| Emotion regulation (T1) | Dissociation (T1) | |||||

| CCT | −1.10* | 0.43 | [−1.83, −0.40] | 0.51* | 0.20 | [0.17, 0.84] |

| Emotion regulation | – | – | – | −0.31*** | 0.03 | [−0.36, −0.27] |

| Internalized behavior problems (T2) | Externalized behavior problems (T2) | |||||

| CCT | −0.55 | 0.48 | [−1.34, 0.25] | 0.55 | 0.48 | [−0.23, 1.34] |

| Emotion regulation | −0.14* | 0.08 | [−0.26, −0.01] | −0.26** | 0.09 | [−0.40, −0.19] |

| Dissociation | 0.86*** | 0.13 | [0.64, 1.11] | 0.56*** | 0.15 | [0.31, 0.81] |

Note. CCT = Cumulative childhood trauma. CI = confidence interval.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

The second mediation analysis showed similar results for the relationship between cumulative childhood trauma and externalized behavior problems. As presented in Table 2, both emotion regulation and dissociation had a significant effect on externalized behavior problems (β = −0.26, p < 0.01 and β = 0.56, p < 0.001, respectively). The direct effect of cumulative childhood trauma on externalized behavior problems was not significant once controlled for emotion regulation and dissociation (β = 0.55, p = 0.25), suggesting a full mediation effect for externalized behavior problems.

The models explained 26% of the variance of internalized behavior problems and 25% of the variance of externalized behavior problems.

Fig. 3 illustrates the different paths of influence of cumulative childhood trauma on behavior problems and Table 3 displays the estimation results of indirect effects of cumulative childhood trauma on internalized and externalized behavior problems through the two mediators. Results revealed that cumulative childhood trauma affects internalized behavior problems through three mediation paths: through emotion regulation alone (0.15, CI [0.02, 0.39]), through dissociation alone (0.44, CI [0.17, 0.77]), and through the path containing the two mediators (0.29, CI [0.12, 0.54]). The numbers in brackets refer to the estimated indirect effects and their corresponding 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals. The total indirect effect of cumulative childhood trauma on internalized behavior problems through emotion regulation and dissociation was significant (0.89, CI [0.50, 1.33]). Results also showed a total indirect effect of cumulative childhood trauma on externalized behavior problems via the two mediator variables (0.77, CI [0.42, 1.20]). Here again, the three specific indirect effects were significant: (0.29, CI [0.09, 0.63]) for the specific indirect effect passing via emotion regulation, (0.28, [0.11, 0.56]) for the specific indirect effect passing via dissociation and (0.19, [0.08, 0.39]) for the specific indirect effect passing via both emotion regulation and dissociation.

Fig. 3.

The estimated multiple mediator models for the effect of cumulative childhood trauma on behavior problems. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, Note. T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2.

Table 3.

Indirect effects of cumulative childhood trauma on internalized and externalized behavior problems.

| Internalized behavior problems (T2) | Estimate SE | 95% BC Bootstrap CI |

|---|---|---|

| Specific indirect effect via ER | 0.15 | 0.11 [0.02, 0.39] |

| Specific indirect effect via dissociation | 0.44 | 0.18 [0.17, 0.77] |

| Specific indirect effect via ER and dissociation | 0.29 | 0.12 [0.12, 0.54] |

| Total indirect effect | 0.89 | 0.25 [0.50, 1.33] |

| Externalized behavior problems (T2) | ||

| Specific indirect effect via ER | 0.29 | 0.16 [0.09, 0.63] |

| Specific indirect effect via dissociation | 0.28 | 0.13 [0.11, 0.56] |

| Specific indirect effect via ER and dissociation | 0.19 | 0.09 [0.08, 0.39] |

| Total indirect effect | 0.77 | 0.24 [0.42, 1.20] |

Note. CI = Confidence interval, BC = Bias-corrected, ER = Emotion regulation.

A multi-group analysis was conducted to test for possible difference between girls and boys in the two mediation models. A chi-square difference test was used to compare the model where parameters were constrained to equality across sex with the model where parameters were allowed to differ across sex. When the chi-square statistic is non-significant, the constrained model is preferable and the two sex groups do not differ. The chi-square difference test results showed no difference between girls and boys in the first and the second mediation model (ΔX2 = 7.62, p = 0.38; ΔX2 = 11.29, p = 0.13, respectively).

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the possible mediation effect of emotion regulation and dissociation in the relationships between cumulative childhood trauma and internalized and externalized behavior problems in a sample of school-aged CSA victims. In line with our hypotheses and with results of past studies, cumulative childhood trauma was associated with higher levels of emotional dysregulation, dissociation, and behavior problems (Briere, 2006; Choi and Oh, 2014; Hodges et al., 2015; Horan and Widom, 2015). Furthermore, descriptive analyses revealed CSA rarely occurs alone. Coherent with past studies (Turner et al., 2015), our data suggest that 75% of sexually abused children experienced at least one other form of child maltreatment and close to one out of five children experienced three other forms of maltreatment apart from the CSA. These findings underline the relevance of studying the negative outcomes associated with cumulative childhood trauma in sexually abused children.

Furthermore, multiple mediation paths were found. Cumulative childhood trauma was found to be indirectly associated with internalized behavior problems via its effect on emotion regulation, the association between emotion regulation and dissociation, and the effect of dissociation on internalized behavior problems. The same was true for externalized behavior problems. Although emotion regulation and dissociation were measured concurrently, the significant direct effect of emotion regulation on dissociation and the indirect paths including both mediators provide support to previous conceptual and empirical reports suggesting that dissociation could be the result of failed emotion regulation attempts (Chaplo et al., 2015; Kalill, 2013; Sundermann and DePrince, 2015). In addition, the direct and indirect paths identified confirmed the hypothesized associations between emotion regulation, dissociation, and behavior problems. Nonetheless, the sequence identified needs to be interpreted with caution.

Our results are in line with those of Choi and Oh (2014), but they also further our understanding of the associations between cumulative childhood trauma and behavior problems by including dissociation symptoms into the models tested. While the association between dissociation and behavior problems was less documented than the link with emotion regulation, our results converge with those of Hagan et al. (2015), Kisiel and Lyons (2001), and Ross-Gower et al. (1998), showing that this is a relevant variable to explore when aiming to understand the mechanisms linking cumulative childhood trauma and behavior problems in childhood.

Finally, when emotion regulation and dissociation were accounted for, the effect of cumulative childhood trauma on externalized behavior problems became non-significant, pointing to a complete mediation effect of these variables. Regarding internalized behavior problems, three indirect paths starting with cumulative childhood trauma and including these variables were significant. These results highlight that emotion regulation and dissociation appears to play a major role in the relations between cumulative childhood trauma and behavior problems in our school-age sample. These findings, if replicated, have significant implications for practice.

5. Implications and contributions

While our findings still need replication, especially with non-concurrent measures of emotion regulation and dissociation, important clinical implications can be derived. Cumulative childhood trauma, emotion regulation, dissociation, and behavior problems should be routinely assessed when sexually abused children consult for treatment. Parent-report validated questionnaires, like those used in this study, are easily available and could provide useful information. Psychiatrists and mental health practitioners should be aware of the patterns of association between study’s variables in order to elaborate efficient treatment plans. To reduce behavior problems, professionals might need to specifically address emotion regulation competencies and dissociation using targeted therapeutic strategies (e.g., emotion awareness skills, emotion understanding skills, empathy skills, grounding strategies, dissociation-focused interventions) (Silberg, 2014; Southam-Gerow, 2013). Emotion regulation appears to be of particular relevance.

6. Limitations

Research implications can also be derived from this study and are directly related with its limitations. The two mediators of interest (emotion regulation and dissociation) were both assessed at T1. While previous findings and theoretical models advocate for a direction of the effect where emotion regulation deficits precede dissociation symptoms, the cross-sectional nature of the relation between these two variables in the present study does not allow to draw such a conclusion. Therefore, it could be argued that dissociation symptoms might predict emotion regulation deficits. In line with this hypothesis, Hulette (2011) found that dissociation predicted alexithymia and difficulty describing feelings in adults, two constructs related to emotion regulation. On the other hand, Kalill’s results (2013) tend to indicate that the relation between emotion regulation and dissociation could be bidirectional. Indeed, emotion regulation was found to mediate the association between peritraumatic dissociation and later dissociation in young adults. Clearly, more studies are needed to be able to confirm the sequence of associations between emotion regulation and dissociation, and only longitudinal designs could achieve such an objective.

Another limitation is that all measures were derived from parent-reports, while it is now recognized that a multi-informant, multi-method approach is ideal in developmental studies. It would be essential to replicate our findings using self-report measures, as well as measures derived from parents, mental health practitioners, and/or teachers. Observational measures could also be used to strengthen the design. While no gender effect were found in the current models, it is still possible that some CSA correlates unfold or evolve differently in boys and girls over the course of longer periods of assessment. For example, the evolution of emotion regulation deficits and dissociation symptoms were found to be gender related in preschool victims of CSA over one year (Bernier et al., 2013; Langevin et al., 2015; Séguin-Lemire et al., 2017).

In conclusion, this study provides meaningful information regarding the short-term correlates of CSA and cumulative childhood trauma in school-age children. Emotion regulation in particular, but also dissociation, appear to be key factors in the well-established association between trauma and later behavior problems. Future studies should pursue this line of investigation to procure valuable knowledge for practitioners working with traumatized children. This enhanced understanding of traumatic dynamics could be useful to foster resilience in children that were, unfortunately, exposed to horrifying events before even reaching adolescence.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the children and the parents who participated in the study and members of the different intervention centers involved namely the Child Protection Clinic of Sainte-Justine Hospital, the Centre d’expertise Marie-Vincent, the Centre d’intervention en abus sexuels pour la famille (CIASF), the Centre jeunesse de la Mauricie et du Centre-du-Québec, and Parents-Unis. The authors also wish to thank Manon Robichaud for data management.

Role of funding source

This research was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR # 235509) awarded to Martine Hébert.

Biographies

Martine Hébert, (Ph.D. in psychology) is the Tier I Canada Research Chair in Interpersonal Traumas and Resilience and co-holder of the Marie-Vincent Interuniversity Chair in Child Sexual Abuse. She is also director of the Sexual Violence and Health Research Team, and full professor at the Department of sexology, Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM), Canada. Her research projects focus on the diversity of profiles in survivors of interpersonal traumas and the evaluation of intervention and prevention programs.

Rachel Langevin, (Ph.D. in psychology) completed her doctoral dissertation exploring emotion regulation in sexually abused children. She is currently completing a post- doctoral scholarship at the Department of Psychology of Concordia University and is involved in research projects examining factors related to the inter-generational trans- mission of violence in at-risk families.

Essaïd Oussaïd, (M.Sc. in Mathematics) is statistical consultant for the Research Chair in Interpersonal Traumas and Resilience.

References

- Achenbach T, Rescorla L. Manual for the ASEBA School-Ages forms & Profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Alink L, Cicchetti D, Kim J, Rogosch F. Mediating and moderating processes in the relation between maltreatment and psychopathology: Mother-child relationship quality and emotion regulation. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2009;37:831–843. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9314-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10802-009-9314-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DC, Modrowski CA, Kerig PK, Chaplo SD. Investigating the dissociative subtype of posttraumatic stress disorder in a sample of traumatized detained youth. Psychol Trauma. 2015;7:465–472. doi: 10.1037/tra0000057. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/tra0000057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier MJ, Hébert M, Collin-Vézina D. Dissociative symptoms over a year in a sample of sexually abused children. J Trauma Dissociation. 2013;14:455–472. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2013.769478. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2013.769478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthelot N, Maheux J, Lemieux R, Normandin L, Ensink K. La dissociation comme médiateur entre l’agression sexuelle et la symptomatologie clinique chez l’enfant. Revue québécoise de psychologie. 2012;33(3):37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Briere J. Dissociative symptoms and trauma exposure: Specificity, affect dysregulation, and posttraumatic stress. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194:78–82. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000198139.47371.54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.nmd.0000198139.47371.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Hodges M, Godbout N. Traumatic stress, affect dysregulation, and dysfunctional avoidance: A structural equation model. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23:767–774. doi: 10.1002/jts.20578. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jts.20578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplo SD, Kerig PK, Bennett DC, Modrowski CA. The roles of emotion dysregulation and dissociation in the association between sexual abuse and self-injury among juvenile justice–involved youth. J Trauma Dissociation. 2015;16:272–285. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2015.989647. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2015.989647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JY, Oh KJ. Cumulative childhood trauma and psychological maladjustment of sexually abused children in Korea: Mediating effects of emotion regulation. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38:296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.09.009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Morris AS. Children’s emotion-related regulation. In: Kail RV, editor. Advances in child development and behavior. Vol. 30. San Diego: Academic Press; 2002. pp. 190–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Hofer C, Sulik MJ, Spinrad TL. Self-regulation, effortful control, and their socioemotional correlates. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of Emotion Regulation. 2. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013. pp. 157–172. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Childhood self-control and adult outcomes: Results from a 30-year longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52:709–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.04.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD. How can self-regulation enhance our understanding of trauma and dissociation? J Trauma Dissociation. 2013;14:237–250. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2013.769398. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2013.769398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith RE, Chesney SA, Heath NM, Barlow MR. Emotion regulation difficulties mediate associations between betrayal trauma and symptoms of posttraumatic stress, depression, and anxiety. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26:376–384. doi: 10.1002/jts.21819. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jts.21819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan MJ, Hulette AC, Lieberman AF. Symptoms of dissociation in a high-risk sample of young children exposed to interpersonal trauma: Prevalence, correlates, and contributors. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:258–261. doi: 10.1002/jts.22003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jts.22003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. The Gilford Press; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hébert M, Langevin R, Daigneault I. The association between peer victimization, PTSD, and dissociation in child victims of sexual abuse. J Affect Disord. 2016;193:227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.080. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hébert M, Parent N. Unpublished document. Montréal, Département de sexologie, Université du Québec à Montréal; Montréal (QC): 2000. Traduction française du Child Dissociative Checklist (CDC) de F. Putnam, K. Helmers, et P. K. Trickett. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges M, Godbout N, Briere J, Lanktree C, Gilbert A, Kletzka NT. Cumulative trauma and symptom complexity in children: A path analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37:891–898. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.04.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan JM, Widom CS. Cumulative childhood risk and adult functioning in abused and neglected children grown up. Dev Psychopathol. 2015;27:927–941. doi: 10.1017/S095457941400090X. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S095457941400090X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulette AC. Doctor of Philosophy. Graduate School of the University of Oregon; 2011. Intergenerational relationships between trauma, dissociation and emotion. [Google Scholar]

- Kalill KS. Doctor of Philosophy. University of Massachusetts Boston; 2013. The role of difficulties in emotion regulation in the relationship between experiences of trauma and later dissociation. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, … Ryan N. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children - present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Spoon J, Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. A longitudinal study of emotion regulation, emotion lability-negativity, and internalizing symptomatology in maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Child Dev. 2013;84:512–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01857.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01857.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisiel CL, Lyons JS. Dissociation as a mediator of psychopathology among sexually abused children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1034–1039. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.7.1034. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.7.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langevin R, Cossette L, Hébert M. Emotion regulation in sexually abused preschoolers. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2016;47:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10578-015-0538-y. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10578-015-0538-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langevin R, Hébert M, Cossette L. Emotion regulation as a mediator of the relation between sexual abuse and behavior problems in preschoolers. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;46:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.02.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langevin R, Hébert M, Cossette L. Unpublished work. Université du Québec à Montréal; Montréal, Québec: 2010. Adaptation française du Emotion Regulation Checklist. [Google Scholar]

- Lanius RA, Vermetten E, Loewenstein RJ, Brand B, Schmahl C, Bremner JD, Spiegel D. Emotion modulation in PTSD: Clinical and neurobiological evidence for a dissociative subtype. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:640–647. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081168. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis T, McElroy E, Harlaar N, Runyan D. Does the impact of child sexual abuse differ from maltreated but non-sexually abused children? A prospective examination of the impact of child sexual abuse on internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;51:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.11.016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behav Res. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniglio R. Significance, nature, and direction of the association between child sexual abuse and conduct disorder: A systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2015;16:241–257. doi: 10.1177/1524838014526068. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1524838014526068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Muthén and Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Powers A, Cross D, Fani N, Bradley B. PTSD, emotion dysregulation, and dissociative symptoms in a highly traumatized sample. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;61:174–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.12.011. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/BF03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam FW, Helmers K, Trickett PK. Development, reliability, and validity of a child dissociation scale. Child Abuse Negl. 1993;17:731–741. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(08)80004-x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(08)80004-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam KT, Harris WW, Putnam FW. Synergistic childhood adversities and complex adult psychopathology. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26:435–442. doi: 10.1002/jts.21833. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jts.21833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross-Gower J, Waller G, Tyson M, Elliott P. Reported sexual abuse and subsequent psychopathology among women attending psychology clinics: The mediating role of dissociation. Br J Clin Psychol. 1998;37:313–326. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1998.tb01388.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1998.tb01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Séguin-Lemire A, Hébert M, Cossette L, Langevin R. A longitudinal study of emotion regulation among sexually abused preschoolers. Child Abuse Negl. 2017;63:307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.027. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields A, Cicchetti D. Emotion regulation among school-age children: The development and validation of a new criterion Q-sort scale. Dev Psychol. 1997;33:906–916. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.6.906. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.33.6.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields A, Dickstein S, Seifer R, Giusti L, Magee KD, Spritz B. Emotional competence and early school adjustment: A study of preschoolers at risk. Early Educ Dev. 2001;12:73–96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15566935eed1201_5. [Google Scholar]

- Shipman K, Zeman J, Penza S, Champion K. Emotion management skills in sexually maltreated and nonmaltreated girls: A developmental psychopathology perspective. Dev Psychopathol. 2000;12:47–62. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400001036. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s0954579400001036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:422–445. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037//1082-989X.7.4.422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberg JL. Dissociative disorders in children and adolescents. In: Rudolph MLKD, editor. Handbook of developmental psychopathology. 3. Springer Science + Business Media; New York, NY: 2014. pp. 761–775. [Google Scholar]

- Southam-Gerow MA. Emotion Regulation in Children and Adolescent: A Practitioner’s Guide. The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenborgh M, van Ijzendoorn MH, Euser EM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. A global perspective on child sexual abuse: Meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreat. 2011;16:79–101. doi: 10.1177/1077559511403920. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077559511403920le. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2). Development and preliminary psychometric data. J Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. doi: 10.1177/019251396017003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sundermann JM, DePrince AP. Maltreatment characteristics and emotion regulation difficulties as predictors of mental health symptoms: Results from a community-recruited sample of female adolescents. J Fam Violence. 2015;30:329–338. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10896-014-9656-8. [Google Scholar]

- Turner HA, Shattuck A, Finkelhor D, Hamby S. Polyvictimization and youth violence exposure across contexts. J Adolesc Health. 2015;58:208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.09.021. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe VV, Wolfe DA, Gentile C, Bourdeau P. History of Victimization Form. London Health Science Centre; London, Ontario: 1987. [Google Scholar]