Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the relationship between the presence and number of restricting symptoms and number of disabilities and subsequent admission to hospice at the end of life.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

Greater New Haven, Connecticut, from March 1998 to December 2014.

Participants

562 decedents from a cohort of 754 persons ≥70 years.

Measurements

Hospice admissions were identified primarily from Medicare claims, while 15 restricting symptoms and disability in 13 activities were assessed during monthly interviews.

Results

During their last year of life, 244 (43.4%) participants were admitted to hospice. The median (IQR) duration of hospice was 12.5 (4–43) days. Although the largest increases were observed in the last two months of life, the prevalence of restricting symptoms and mean number of restricting symptoms and disabilities in the preceding months were high and trending upwards. During a specific month, the likelihood of hospice admission increased by 66% (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.30–2.12) in the setting of any restricting symptoms and by 9% (1.09 [1.05–1.12]) and 10% (1.10 [1.05–1.14]) for each additional restricting symptom and disability, respectively. Each additional month with any restricting symptoms increased the likelihood of hospice admission by 7% (1.07 [1.01–1.13]).

Conclusion

Hospice services appear to be suitably targeted to older persons with the greatest needs at the end of life. The short duration of hospice, however, suggests that additional strategies are needed to better address the high burden of distressing symptoms and disability at the end of life.

Keywords: longitudinal study, hospice, end of life, older persons, disability, restricted activity

INTRODUCTION

The Medicare hospice benefit was established in 1982 to ensure that patients in the last six months of life have access to high-quality palliative care. Despite the tremendous growth in hospice over the past 30 years, concerns have been raised that hospice is often underutilized.1–5 Indeed, the median length of stay in hospice is only about three weeks, and about a third of patients are referred to hospice in the last seven days of life.6 As a possible explanation, access to hospice is constrained by the eligibility requirement that patients have a prognosis of six months or less for a defined set of specific conditions,6 which no longer includes debility.7 As a second explanation, physicians may not weigh the burden of disability in their decision-making about hospice referral, despite evidence that functional status is one of the strongest predictors of mortality among older persons.8–10

Because hospice is designed to ameliorate pain and other distressing symptoms, referral to hospice should be based, at least in part, on the burden of these symptoms; but the short duration of hospice, coupled with preliminary data from our group, suggest otherwise. Specifically, we found that a large proportion of older decedents have a high prevalence of restricting symptoms during the last year of life.11 Moreover, the need for services at the end of life to assist with essential activities of daily living is at least as great for older persons dying from organ failure and frailty as for those dying from a more traditional terminal condition such as cancer, and the need is much greater for those dying from advanced dementia.12 Yet, the evidence indicates that hospice is underutilized for conditions other than cancer.6 As highlighted in a recent Institute of Medicine report,13 failing or delaying to refer older persons to hospice at the end of life can place a high burden on caregivers14 and result in patient suffering.15

The objective of the current study was to evaluate the relationship between three clinically relevant exposures, namely the presence and burden of restricting symptoms and the burden of disability, and subsequent admission to hospice in the last year of life. We postulated that these associations would be weak or nonexistent. To test this hypothesis, we used high quality data from a unique longitudinal study of older persons that includes monthly assessments of restricting symptoms and disability over more than 15 years and information on hospice admissions obtained from Medicare claims.

METHODS

Study Population

Participants were drawn from an ongoing longitudinal study of 754 community-living persons, aged ≥70, who were initially nondisabled in basic activities of daily living.16, 17 Potential participants were members of a large health plan (managed care and fee for service) and were excluded for significant cognitive impairment with no available proxy,18 life expectancy <12 months, plans to move out of the area, or inability to speak English. Only 4.6% of persons refused screening, and 75.2% of those eligible agreed to participate and were enrolled from March 1998 to October 1999. The study was approved by the Yale Human Investigation Committee, and all participants provided informed consent.

Analytic Sample

The current analysis focused on the last year of life for two reasons: first, Medicare coverage of hospice requires a physician to certify that life expectancy is ≤6 months if the terminal condition runs its normal course; and second, median survival in hospice was only two weeks in our earlier study.19 Of the 623 decedents through December 2014, 29 (4.7%) had dropped out of the study after a median follow-up of 27 months, 15 (2.4%) had been admitted to hospice more than a year prior to their death, 14 (2.2%) died suddenly and would not have been considered for hospice,12 and 3 (0.5%) did not have sufficient information on restricting symptoms and disability, leaving 562 participants in the analytic sample.

Data Collection

Comprehensive home-based assessments were completed at baseline and subsequently at 18-month intervals for up to 198 months (except for 126 months), while telephone interviews were completed monthly through December 2014, with a completion rate of 99%. When participants were unable to complete the monthly interviews, proxy data were obtained using a standard protocol.18 Of the 6,629 monthly interviews in the current analysis, 45.0% were completed by a proxy. The accuracy of these proxy reports was moderate to substantial,20 with Kappa=0.66 for restricted activity11 and intraclass correlation coefficient=0.56 for burden of disability. Deaths were ascertained from the local obituaries and/or an informant. The cause of death was coded, using information from the death certificate, by a certified nosologist. During the comprehensive assessments, data were collected on demographic characteristics, nine self-reported, physician-diagnosed chronic conditions, body mass index, cognitive status,21 depressive symptoms,22 and social support.23

Ascertainment of Restricting Symptoms

During the monthly interviews, the occurrence of restricting symptoms was ascertained using a standard protocol.16 First, participants were asked two questions related to restricted activity: “Since we last talked, have you stayed in bed for at least half a day due to an illness, injury, or other problem?” and “Since we last talked, have you cut down on your usual activities due to an illness, injury, or other problem?” Second, if participants answered “yes” to either question, they were asked whether they had any of 24 pre-specified symptoms/problems since the last interview.24–27 Third, immediately after each “yes” response to a specific symptom/problem, participants were asked, “Did this cause you to stay in bed for at least ½ day or cut down on your usual activities?” As in prior studies,11, 28 the current analysis focused on 15 restricting symptoms: fatigue; musculoskeletal pain; dyspnea; chest pain/tightness; nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea; depression; anxiety; arm/leg weakness; difficulty sleeping; dizziness/unsteadiness; difficulty with memory/thinking; swelling in feet/ankles; cold/flu symptoms; poor/decreased vision; and urinary frequency, pain or incontinence. The test-retest reliability of the protocol was high, with kappa=0.90 for restricted activity and ≥0.75 for all restricting symptoms.11 Data on restricted activity were missing for only 0.6% of the observations.

Assessment of Disability

Complete details regarding the assessment of disability are provided elsewhere.17, 18, 29 During the monthly interviews, participants were asked, “At the present time, do you need help from another person to (complete the task)?” for each of four basic activities (bathing, dressing, walking, and transferring), five instrumental activities (shopping, housework, meal preparation, taking medications, and managing finances), and three mobility activities (walk 1/4 mile, climb flight of stairs, and lift/carry ten pounds). For these 12 activities, disability was operationalized as the need for personal assistance or unable to do the task. Participants were also asked about a fourth mobility activity, “Have you driven a car during the past month?” Participants who responded “No” were considered to be “disabled” in driving.29 To address the small amount of missing data on disability (0.9% of observations), multiple imputation was used with 100 random draws per missing observation.30

Admission to hospice

Hospice admissions through 2014 were identified primarily using Medicare claims.31 For 3 participants, the admission was ascertained from a proxy informant and confirmed by review of medical records and death certificate.

Condition Leading to Death

Information from death certificates and the comprehensive assessments was used to classify the condition leading to death, according to the protocol provided in Supplementary Table S1.12

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome was admission to hospice. Characteristics of the analytic sample were summarized according to hospice status using information from the comprehensive assessment that immediately preceded the study period (i.e. last year of life), except for age, living situation, and number of disabilities, which were ascertained from the telephone interview 12 months prior to death. The likelihood of hospice admission was evaluated for each of the conditions leading to death.

The prevalence of restricting symptoms was calculated by dividing the number of participants with any restricting symptoms in a specific month by the total number of participants who completed an interview that month. The mean number (i.e. burden) of restricting symptoms (possible range: 0–15) and disabilities (possible range: 0–13), respectively, were also calculated each month.

We used Cox proportional hazards models to evaluate the associations between each of the three exposures and time to hospice admission during the last year of life.32 Because all exposure variables were time-varying, their value could change monthly. Participants were censored at the time of death or last completed interview if they dropped out of the study before their death (n=5: 2–hospice, 3–no hospice). The association between each exposure and hospice admission was expressed as a hazard ratio (HR). For the presence of any restricting symptoms, the HR denotes the likelihood of hospice admission at month t (current month) based on the presence (vs. absence) of any restricting symptoms at month t-1 (prior month). For the two other exposures, the HR denotes the relative risk for hospice admission at month t per one-unit increment in the number of restricting symptoms and disabilities at month t-1, respectively. These models were subsequently rerun with the following covariates: age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, living situation, number of chronic conditions, cognitive impairment, depression symptoms, low social support, and number of months since last comprehensive assessment. The overall fit of the final models was assessed with residual plots.

To enhance the clinical interpretation of our results, we calculated the adjusted absolute risk difference (ARD) for the presence of any restricting symptoms in month t-1, based on the cumulative probability of hospice admission over 12 months using the same time-varying Cox regression model,31 and we estimated 95% confidence intervals using 100 bootstrapped samples.33 The ARD denotes the difference in average probability of hospice admission between participants who had any restricting symptoms in month t-1 and those who did not. These calculations were based on marginal probabilities of the outcome, assuming that all participants were exposed and all participants were unexposed, respectively, while holding the covariates fixed.

To determine the association between the cumulative burden of restricting symptoms (during the exposure period) and subsequent hospice admission, we refit the Cox model, substituting the cumulative number of months with any restricting symptoms (for the presence of any restricting symptoms at month t-1) as a time-varying exposure, whose value increased by one for each month a participant reported any restricting symptoms.

In a final set of analyses, the associations between the time-varying exposures and admission to hospice were evaluated according to the condition leading to death. All analyses were performed using SAS V9.4, and P<.05 (2-tailed) was used to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Of the 562 decedents, 244 (43.4%) were admitted to hospice during their last year of life. As shown in Table 1, persons admitted to hospice were slightly older and more likely to have cognitive impairment than those who were not admitted to hospice. The most common condition leading to death was frailty, followed by organ failure, advanced dementia and cancer (Supplementary Table S2). The likelihood of hospice admission was highest for cancer and advanced dementia, lowest for frailty and other conditions, and intermediate for organ failure. The mean (SD) and median (IQR) duration of hospice were 40.2 (69.3) and 12.5 (4–43) days, respectively, with no significant differences according to the condition leading to death (P=.768).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Decedents Prior to Last Year of Lifea

| Characteristic | All N = 562 |

Admitted to Hospice N = 244 |

Not Admitted to Hospice N = 318 |

P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 86.6 (6) | 87.3 (5.8) | 86.1 (6.1) | .019 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 351 (62.5) | 159 (65.2) | 192 (60.4) | .245 |

| Non-Hispanic white, n (%) | 507 (90.2) | 218 (89.3) | 289 (90.9) | .543 |

| Education in years, mean (SD) | 11.9 (2.9) | 11.9 (2.9) | 11.8 (2.9) | .703 |

| Living situation | .532 | |||

| Community, alone, n (%) | 186 (33.1) | 75 (30.7) | 111 (34.9) | |

| Community, with others, n (%) | 249 (44.3) | 110 (45.1) | 139 (43.7) | |

| Nursing home, n (%) | 127 (22.6) | 59 (24.2) | 68 (21.4) | |

| Number of chronic conditions, mean (SD) | 2.6 (1.3) | 2.6 (1.3) | 2.5 (1.3) | .605 |

| Cognitive impairmentc, n (%) | 209 (37.2) | 102 (41.8) | 107 (33.7) | .047 |

| Depressive symptomsd, n (%) | 148 (26.3) | 68 (27.9) | 80 (25.2) | .469 |

| Low social supporte, n (%) | 140 (24.9) | 62 (25.4) | 78 (24.5) | .811 |

| Number of disabilitiesf, mean (SD) | 7.0 (± 4.6) | 7.3 (± 4.7) | 6.7 (± 4.5) | .102 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Characteristics were ascertained during the comprehensive assessment that preceded the last year of life except for age, living situation, and number of disabilities, which were ascertained in month 1 of the last year of life.

For statistical comparisons between decedents who were and were not admitted to hospice in their last year of life, the chi-square test was used for dichotomous variables and living situation, and t-test was used for continuous variables.

Defined as score less than 24 on Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination.

Defined as score of 20 or greater on Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale.

Score < 19 on Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Scale.

Out of 13 basic, instrumental, and mobility activities. Only 1 (0.4%) and 8 (2.5%) decedents who were admitted to hospice and not admitted to hospice, respectively, had no disabilities.

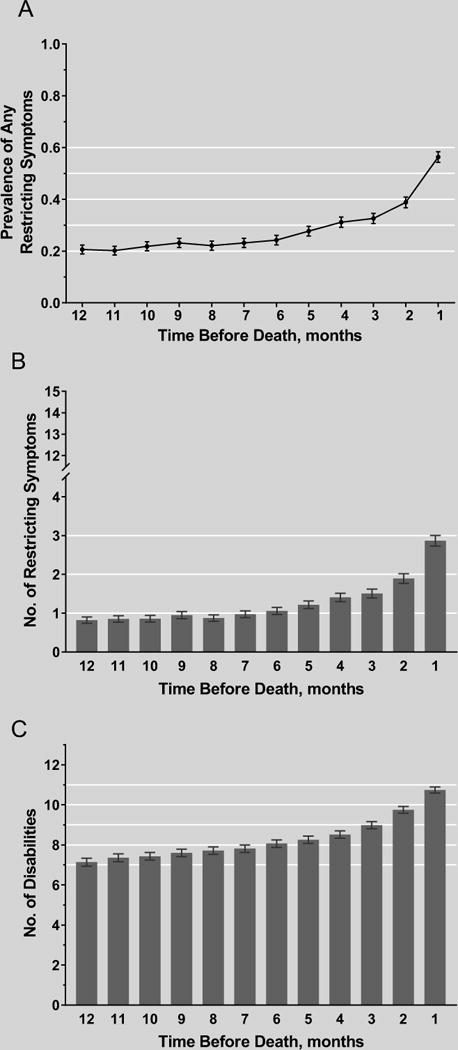

Figure 1 provides information about exposure to restricting symptoms and disability. The prevalence of restricting symptoms (Panel A) was relatively flat (0.20–0.24) until about six months prior to death when the value started increasing, reaching a peak of 0.56 one month prior to death. Similarly, the mean number of restricting symptoms (Panel B) was relatively flat (0.8–1.0) until about six months prior to death when the value started increasing, with the most pronounced increase observed in the last two months of life. In contrast, the mean number of disabilities (Panel C) increased progressively throughout the last year of life, from 7.1 twelve months prior to death to 10.7 one month prior to death, with the greatest increases observed in the last two months of life. These patterns were generally similar for participants who were and were not admitted to hospice (Supplementary Figure S1), although the values for each exposure were greater for the former than the latter, particularly in the month before death.

Figure 1.

Exposure to restricting symptoms and disability in the last year of life among all participants. For each panel, the error bars represent 1 SE. The maximum number of restricting symptoms and disabilities were 15 and 13, respectively.

Table 2 shows the associations between the three time-varying exposures and admission to hospice. In the setting of any restricting symptoms during a specific month, the likelihood of hospice admission within the following month increased by 66%, after adjustment for covariates. The corresponding increase per number of restricting symptoms was 9%. For each additional disability during a specific month, the likelihood of hospice admission within the following month increased by 10%. When evaluated as a time-varying cumulative exposure, each additional month with any restricting symptoms (up to month t-1) increased the likelihood of hospice admission at month t by 7% in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses. The adjusted absolute risk difference for the presence of any restricting symptoms in a specific month, based on the cumulative probability of hospice admission over 12 months, was 15.3% (95% CI, 7.5%–24.1%).

Table 2.

Associations Between Time-Varying Exposures and Admission to Hospice in Last Year of Life

| Time-Varying Exposure | Unadjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted a Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Specific month b | ||

| Any restricting symptoms | 1.62 (1.27–2.07) | 1.66 (1.30–2.12) |

| Per no. restricting symptoms c | 1.08 (1.04–1.12) | 1.09 (1.05–1.12) |

| Per no. disabilities d | 1.10 (1.05–1.14) | 1.10 (1.05–1.14) |

| Cumulative number of months e | ||

| Any restricting symptoms | 1.07 (1.01–1.12) | 1.07 (1.01–1.13) |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity, years of education, living situation, number of chronic conditions, cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, low social support and months since prior comprehensive assessment.

Results reflect the marginal (i.e. average) effect of each exposure at month t-1 on hospice admission at month t.

Possible range: 0 to 15

Possible range: 0 to 13

Results reflect the effect of each additional month with any restricting symptoms as a time-varying exposure (up to month t-1) on hospice admission at month t.

As shown in Table 3, the associations between the time-varying exposures and admission to hospice, as denoted by adjusted hazard ratios, were weakest for advanced dementia but were generally consistent across the four other conditions leading to death, although several confidence intervals spanned one. The point estimates for the presence and number of restricting symptoms in a specific month were highest for cancer, while the point estimates for the number of disabilities in a specific month were highest for frailty and other conditions. For the cumulative number of months with any restricting symptoms, the association was statistically significant only for organ failure.

Table 3.

Associations Between Time-Varying Exposures and Admission to Hospice in Last Year of Life According to Condition Leading to Death

| Time-Varying Exposure | Cancer N = 100 |

Advanced Dementia N = 108 |

Organ Failure N = 114 |

Frailty N = 167 |

Other Condition N = 73 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI) a | |||||

| Specific month b | |||||

| Any restricting symptoms | 2.72 (1.56–4.75) | 1.31 (0.81–2.14) | 2.03 (1.13–3.67) | 1.53 (0.83–2.83) | 1.50 (0.59–3.82) |

| Per no. restricting symptoms c | 1.16 (1.05–1.27) | 1.05 (0.97–1.13) | 1.07 (0.99–1.15) | 1.11 (1.01–1.23) | 1.14 (0.98–1.33) |

| Per no. disabilities d | 1.12 (1.04–1.21) | 1.05 (0.89–1.24) | 1.13 (1.00–1.29) | 1.21 (1.06–1.38) | 1.21 (1.01–1.44) |

| Cumulative number of months e | |||||

| Any restricting symptoms | 1.06 (0.94–1.20) | 0.94 (0.84–1.05) | 1.17 (1.01–1.37) | 1.14 (0.98–1.33) | 1.08 (0.92–1.27) |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity, years of education, living situation, number of chronic conditions, cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, low social support and months since prior comprehensive assessment.

Results reflect the marginal (i.e. average) effect of each exposure at month t-1 on hospice admission at month t.

Possible range: 0 to 15

Possible range: 0 to 13

Results reflect the effect of each additional month with any restricting symptoms as a time-varying exposure (up to month t-1) on hospice admission at month t.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective longitudinal study of older persons, we found strong and consistent associations between three clinically relevant exposures and subsequent admission to hospice in the last year of life. During a specific month, the likelihood of hospice admission increased by 66% in the setting of any restricting symptoms and by 9% and 10% for each additional restricting symptom and disability, respectively. About four out of every nine participants were admitted to hospice, although the duration of hospice was relatively short, with a mean of 40 days and median of only 12.5 days. The timing of hospice admission may reflect the course of restricting symptoms and disability, which did not increase greatly in severity until the last two months of life.

Our results suggest that decisions about hospice admission at the end of life are based, at least in part, on the presence and burden of restricting symptoms and disability. We found that the likelihood of hospice admission increased by 7% for each additional month with any restricting symptoms. In absolute terms, the average probability of hospice admission was 15% higher in the last year of life among participants who had any restricting symptoms in a specific month than those who did not.

Based on prior literature suggesting that hospice is often underutilized,1–5 especially for conditions other than cancer,6 we had expected to find weak to no associations between our three exposures and subsequent admission to hospice. Contrary to our expectations, we found that the associations were weak to nonexistent only for advanced dementia. Although these results should be interpreted cautiously given the limited power to detect statistically significant subgroup differences, estimating life expectancy for advanced dementia is difficult,34 making referral to hospice particularly challenging.

Although the largest increases were observed in the last two months of life, the prevalence of restricting symptoms and mean number of restricting symptoms and disabilities in the preceding months were high and trending upwards. Whether earlier referral to hospice would have alleviated the burden of distressing symptoms and disability is uncertain. In an earlier study,28 we found that the number of restricting symptoms at the end of life decreased significantly after the start of hospice.

Prior reports have raised concerns that the Medicare Hospice Benefit may not adequately address the care needs of persons whose illnesses result in a prolonged period of severe disability.1, 3, 4 In the setting of distressing symptoms and progressive disability, an alternative to hospice at the end of life is palliative care. Prior studies that have shown beneficial effects of palliative care on symptom burden, although the benefit on functional outcomes is less certain.35, 36 The absence of information on receipt of palliative care before the start of hospice is a limitation of the current study.

Several other limitations warrant comment. First, because participants were members of a single health plan in a small urban area in Connecticut, our results may not be generalizable to older persons in other settings or states. However, the demographic characteristics of our cohort reflect those of older persons in New Haven County, Connecticut, which are similar to the characteristics of the US population as a whole, with the exception of race/ethnicity.37 Also, utilization of hospice in the current study (43.4% of deaths) was comparable to national estimates (44.6% of deaths).38 Second, the use of information from death certificates is an imperfect strategy for classifying conditions leading to death. Previous research has shown that the concordance between coding of death certificates by a nosologist and an adjudicated cause of death is high for cancer and moderate for congestive heart failure and chronic lung disease but only fair for dementia,39 largely because of underreporting of dementia on death certificates. We used data from cognitive testing in addition to coding by a nosologist to classify advanced dementia as a condition leading to death. Third, disease-specific information was not available on severity of illness. Restricting symptoms and disability are common manifestations of severity of illness in older persons. Fourth, a substantial minority of the monthly interviews were completed by proxies. This limitation, which is inherent in end-of-life studies, is diminished by the relatively high concordance between proxy and participant reports for restricting symptoms and disability.

Our study included monthly assessments of restricting symptoms and disability over an extended period of time, with little missing data and few losses to follow-up for reasons other than death. To our knowledge, comparable data are available in no other study. Additional strengths of the study include the high participation rate and use of Medicare claims to ascertain hospice admissions. Our focus on symptoms leading to restricted activity and disability in basic, instrumental and mobility activities enhances the clinical relevance of our findings because proper management of these symptoms and disabilities may substantially improve quality of life while reducing caregiver burden.

In summary, hospice services appear to be suitably targeted to older persons with the greatest needs at the end of life. The short duration of hospice, however, suggests that additional strategies are needed to better address the high burden of distressing symptoms and disability at the end of life.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure S1. Exposure to restricting symptoms and disability in the last year of life according to admission to hospice. For each panel, the error bars represent 1 SE. The maximum number of restricting symptoms and disabilities were 15 and 13, respectively.

Supplementary Table S1. Protocol for Classifying the Condition Leading to Death.

Supplementary Table S2. Likelihood of Hospice Admission for Conditions Leading to Death.

Acknowledgments

We thank Denise Shepard, BSN, MBA, Andrea Benjamin, BSN, Barbara Foster, and Amy Shelton, MPH for assistance with data collection; Wanda Carr and Geraldine Hawthorne, BS, for assistance with data entry and management; Peter Charpentier, MPH for design and development of the study database and participant tracking system; and Joanne McGloin, MDiv, MBA for leadership and advice as the Project Director.

Role of the Sponsors:

The organizations funding this study had no role in the design or conduct of the study; in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

The work for this report was funded by grants from the National Institute on Aging (R01AG17560). The study was conducted at the Yale Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30AG21342). Dr. Gill is the recipient of an Academic Leadership Award (K07AG043587) from the National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

DR. THOMAS M. GILL (Orcid ID : 0000-0002-6450-0368)

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions:

Dr. Gill had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors meet the criteria for authorship stated in the Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals.

Study concept and design: Gill, Allore

Acquisition of data: Gill, Leo-Summers, Gahbauer

Analysis and interpretation of data: Gill, Han, Leo-Summers, Gahbauer, Allore

Preparation of manuscript: Gill, Han, Allore

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Gill, Han, Leo-Summers, Gahbauer, Allore

Statistical analysis: Han, Allore

References

- 1.Casarett DJ. Rethinking Hospice Eligibility Criteria. JAMA. 2011;305:1031–1032. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kutner JS. An 86-year-old woman with cardiac cachexia contemplating the end of her life: review of hospice care. JAMA. 2010;303:349–356. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meier DE. When pain and suffering do not require a prognosis: working toward meaningful hospital-hospice partnership. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:109–115. doi: 10.1089/10966210360510226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Unroe KT, Meier DE. Quality of hospice care for individuals with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1212–1214. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubin R. Improving the quality of life at the end of life. JAMA. 2015;313:2110–2112. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.4234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Facts and Figures. Hospice Care in America. 2013 (Accessed April 13, 2017, at http://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/Statistics_Research/2013_Facts_Figures.pdf)

- 7.Hedlund CT, Sollins HL. Adult failure to thrive and debility can no longer be principal diagnoses on hospice claim forms. 2013 Nov 26; https://www.bakerdonelson.com/adult-failure-to-thrive-and-debility-can-no-longer-be-principal-diagnoses-on-hospice-claim-forms. Accessed May 8, 2017.

- 8.Harrold J, Rickerson E, Carroll JT, et al. Is the palliative performance scale a useful predictor of mortality in a heterogeneous hospice population? J Palliat Med. 2005;8:503–509. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inouye SK, Peduzzi PN, Robison JT, et al. Importance of functional measures in predicting mortality among older hospitalized patients. JAMA. 1998;279:1187–1193. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.15.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carey EC, Walter LC, Lindquist K, et al. Development and validation of a functional morbidity index to predict mortality in community-dwelling elders. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:1027–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40016.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaudhry SI, Murphy TE, Gahbauer E, et al. Restricting symptoms in the last year of life: a prospective cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1534–1540. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.8732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Han L, et al. Trajectories of disability in the last year of life. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1173–1180. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.IOM (Institute of Medicine) Dying in America: Improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Covinsky KE, Goldman L, Cook EF, et al. The impact of serious illness on patients’ families. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. JAMA. 1994;272:1839–1844. doi: 10.1001/jama.272.23.1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desbiens NA, Wu AW. Pain and suffering in seriously ill hospitalized patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:S183–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gill TM, Desai MM, Gahbauer EA, et al. Restricted activity among community-living older persons: incidence, precipitants, and health care utilization. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:313–321. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-5-200109040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardy SE, Gill TM. Recovery from disability among community-dwelling older persons. JAMA. 2004;291:1596–1602. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.13.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gill TM, Hardy SE, Williams CS. Underestimation of disability among community-living older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1492–1497. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stabenau HF, Morrison LJ, Gahbauer EA, et al. Functional trajectories in the year before hospice. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13:33–40. doi: 10.1370/afm.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kramer MS, Feinstein AR. Clinical biostatistics. LIV. The biostatistics of concordance. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;29:111–123. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, et al. Two shorter forms of the CES-D Depression Symptoms Index. J Aging Health. 1993;5:179–193. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rakowski W, Julius M, Hickey T, et al. Daily symptoms and behavioral responses. Results of a health diary with older adults. Med Care. 1988;26:278–297. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198803000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verbrugge LM, Ascione FJ. Exploring the iceberg. Common symptoms and how people care for them. Med Care. 1987;25:539–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brody EM, Kleban MH. Day-to-day mental and physical health symptoms of older people: a report on health logs. Gerontologist. 1983;23:75–85. doi: 10.1093/geront/23.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tinetti ME, Mendes de Leon CF, Doucette JT, et al. Fear of falling and fall-related efficacy in relationship to functioning among community-living elders. J Gerontol Med Sci. 1994;49:M140–M147. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.3.m140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheraghlou S, Gahbauer EA, Leo-Summers L, et al. Restricting Symptoms Before and After Admission to Hospice. Am J Med. 2016;129:754.e757–754.e715. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Murphy TE, et al. Risk factors and precipitants of long-term disability in community mobility: a cohort study of older persons. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:131–140. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-156-2-201201170-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gill TM, Guo Z, Allore HG. Subtypes of disability in older persons over the course of nearly 8 years. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:436–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01603.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gill TM, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA, et al. The course of disability before and after a serious fall injury. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1780–1786. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cox DR. Partial likelihood. Biometrika. 1975;62:269–276. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Effron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. London: Chapman & Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mitchell SL. CLINICAL PRACTICE. Advanced Dementia. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2533–2540. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1412652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gomes B, Calanzani N, Higginson IJ. Benefits and costs of home palliative care compared with usual care for patients with advanced illness and their family caregivers. JAMA. 2014;311:1060–1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelley AS, Morrison RS. Palliative Care for the Seriously Ill. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:747–755. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1404684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.US Census Bureau. American FactFinder. http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml. Accessed April 13, 2017.

- 38.Hospice Facts & Figures. 2012 (Accessed April 13, 2017, at http://www.nhpco.org/press-room/press-releases/hospice-facts-figures)

- 39.Ives DG, Samuel P, Psaty BM, et al. Agreement between nosologist and cardiovascular health study review of deaths: implications of coding differences. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:133–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02056.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1. Exposure to restricting symptoms and disability in the last year of life according to admission to hospice. For each panel, the error bars represent 1 SE. The maximum number of restricting symptoms and disabilities were 15 and 13, respectively.

Supplementary Table S1. Protocol for Classifying the Condition Leading to Death.

Supplementary Table S2. Likelihood of Hospice Admission for Conditions Leading to Death.