Abstract

Background/Objectives

Social support can prevent or delay long-term nursing home placement (NHP). The purpose of our study was to understand how the availability of a caregiver can impact NHP following ischemic stroke, and how this differentially affects subgroups.

Design

Nested cohort study

Setting

Nationally-based REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study

Participants

Stroke survivors aged 65 to 100 (n = 256 men, n = 304 women)

Measurements

Data were from Medicare claims January 2003–December 2013 and REGARDS baseline interviews conducted January 2003–October 2007. Caregiver support was measured by asking, “If you had a serious illness or became disabled, do you have someone who would be able to provide care for you on an on-going basis?” Diagnosis of ischemic stroke was derived from inpatient claims. NHP was determined using a validated claims algorithm for stays ≥100 days. Risk was estimated using Cox regression.

Results

Within 5 years of stroke, 119 (21.3%) were observed to have NHP. Risk of NHP was greater among those lacking available caregivers (log-rank p <0.01). After adjustment for covariates, lacking an available caregiver increased the risk of NHP following stroke within 1 year by 70% (HR1-year 1.70, 95% CI1-year 0.97–2.99) and within 5 years by 68% (HR5-year 1.68, 95% CI1-year 1.10–2.58). The effect of caregiver availability on NHP was limited to men (HR5-year 3.15, 95% CI5-year 1.49–6.67).

Conclusion

Among men over 65 years old surviving ischemic stroke, the lack of an available caregiver is associated with triple the risk of NHP within 5 years.

Keywords: Stroke, Caregiving, Social Support

Introduction

As a leading cause of long-term disability, stroke can be devastating—permanently altering the ability to care for one’s self and thereby limiting the ability to live independently.1–3 In recent years, stroke mortality has declined due in part to improved treatments and other medical advancements.4 Despite these advances to lower incidence and improve survival, stroke remains a significant cause of impairments requiring some form of long-term care. Nearly 70% of those with severe stroke will require nursing home care, especially women and those who are older at stroke onset.5–7

When it comes to long-term care, Americans prefer to remain at home with family support rather than institutionalization.8 In fact, only 29% of adults say they are willing to move into a nursing home if they become disabled, compared with 75% who would rather rely on an informal caregiver.9 Although nursing home placement (NHP) is inevitable for some, social support can substitute or delay this outcome.5,10 While most individuals believe they have someone who can take care of them if they become ill or disabled, it is not known whether this affects NHP.11 The purpose of our study was to better understand how social support affects NHP following stroke. With the demand for long-term care services expected to rise as the U.S. population ages and workforce and nursing home bed shortfalls predicted, understanding factors associated with NHP and encouraging community-living is a critical public health challenge.12–14 We hypothesized that lacking social support, specifically lacking a caregiver, would be an important risk factor of NHP. Furthermore, we investigated whether population subgroups may be especially vulnerable, including men and those with low income.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations and Participant Consents

Consent was obtained initially by telephone and later in writing during the in-person evaluation. The institutional review boards of participating institutions approved the study methods.

Methods

Participants

We conducted a nested cohort study within the REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study. REGARDS was designed to investigate causes of regional and black-white disparities in stroke mortality with oversampling of blacks and residents of the Stroke Belt.15 A detailed description of the sampling, recruitment, and telephone interviewing procedures for REGARDS have been described elsewhere.16 Briefly, using a commercially available list, REGARDS recruited participants aged 45 years or older, English-speaking, community-dwelling, and free of medical conditions preventing follow-up. Baseline interviews and in-home visits were conducted from January 2003 through October 2007, resulting in 30,239 participants. Using a computer-assisted telephone interview, interviewers obtained demographics, medical history and risk factors.

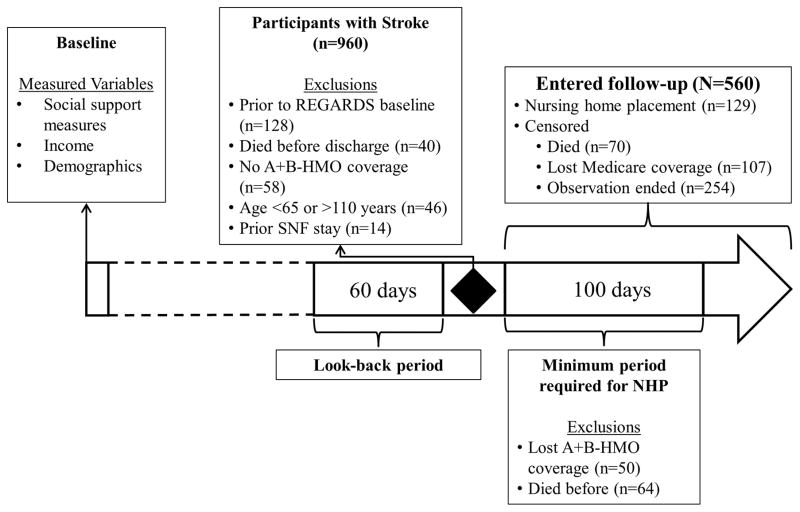

We analyzed data from the participants’ baseline interviews linked with Medicare claims data. The methods for the linkage are described in detail elsewhere.17 Briefly, linkages were conducted using participants’ social security numbers with matches confirmed by sex and birthdate. Data were extracted from multiple Medicare files, including the beneficiary summary file, inpatient file, outpatient file, skilled nursing facility (SNF) file, and carrier file. Our analysis included participants hospitalized for ischemic stroke between September 1, 2003 and September 30, 2013. Ischemic stroke was identified from the inpatient file by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision diagnosis codes: 433.x1, 434.x1, and 436. These codes have been validated in the primary diagnosis position to have a positive predictive value of 92.6% and specificity of 99.8%.18 Using the codes in any position, the positive predictive value has been shown to be 79.5% and the specificity 99.7%.19 Due to concerns with low sensitivity using only primary diagnosis (59.5%), we included diagnosis codes in the top three positions. 18,19 In order to ensure participants’ claims data were complete and they were community-dwelling, a “look-back” period of 60 days prior to stroke admission date was constructed (this corresponds to the Medicare SNF benefit, which renews after 60 days without a SNF claim). During the look-back period, participants for this study were required to have maintained traditional Medicare coverage, defined as parts A and B, without managed care (i.e. Medicare Advantage plans), and were excluded if they had a SNF claim during this period. A “look-forward” period was constructed beginning with the date of discharge following stroke through 100 days. This corresponds to the minimum period required to identify NHP (described below). Participants were excluded if they lost coverage, enrolled in managed care, or died during this period. Among 20,403 REGARDS participants linked to Medicare claims, 960 with ischemic stroke were identified (1,291 events). Figure 1 details exclusion criteria, which included 128 whose strokes occurred prior to baseline interview, 40 participants that died during hospitalization, 58 participants who did not meet coverage criteria, 46 participants that were <65 or >110 years of age, and 14 participants with SNF stays. During the look-forward period, 50 participants were excluded due to their Medicare coverage and 64 participants died. The final analysis considered 560 participants.

Figure 1. Study design flow diagram.

Note. HMO = health maintenance organization (e.g. Medicare Advantage); SNF = skilled nursing facility; NHP = nursing home placement

Measures

The primary outcome of interest was time-to-NHP following hospital discharge for ischemic stroke. We defined NHP as a stay exceeding 100 days, which corresponds to depletion of the Medicare SNF benefit. A validated, claims-based algorithm was used to identify NHP. 20 The algorithm relies on SNF claims paired with physician point of service claims for custodial care observed consecutively for at least 100 days and has 87.0% sensitivity and 96.0% specificity.20 The date of NHP was considered date of admission for SNF stays that exceeded 100 days. Time-to-NHP began the day after hospital discharge until whichever came first: NHP, eligible Medicare coverage lost, death, or the end of available follow-up data (December 31, 2013). Analyses were restricted to time-to-NHP of 1 and 5 years.

The primary exposure variable was lack of an available caregiver, determined from the baseline interview question, “if you had a serious illness or became disabled, do you have someone who would be able to provide care for you on an on-going basis?” Among those with an available caregiver, the relationship (i.e. spouse/partner, child, sibling, other family, other) was collected. Other measures of social support assessed included living alone, marital status, and the number of relatives participants “feel close to,” categorized as ≤3, 4–5, or ≥6.

Other baseline characteristics were selected a priori including race, sex, and income because of known associations with NHP.1,21 Annual household income was collected in increments and based on the distribution, categorized as <$20,000, $20,000 to $50,000, and ≥$50,000. Participants who refused to state income had different distributions of characteristics, including NHP, from those with known incomes. The main analysis was conducted with this group separately. In stratified analyses, low income was defined as annual household income <$20,000 compared to all other incomes, wherein this category was statistically significant in the main analysis. Additionally, due to similar effect sizes and direction, declining to state income was combined with the income group ≥$20,000 per year for stratified analyses to simplify the interpretation. Sensitivity analyses combining and excluding those declining to state income had similar results. We also conducted sensitivity analyses including dual Medicare and Medicaid eligibility that produced similar results. Because using the income variable provides more information and low income was highly correlated with dual-eligibility (Pearson’s ρ=0.406, p<0.001), our final analyses adjust only for income.

Due to the increased risk of NHP associated with dementia and/or other forms of cognitive impairment, claims data were used to identify diagnoses of dementia and dementia-like diseases including Alzheimer’s Disease (hereafter “cognitive impairment”).1,21 We used International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes detailed by Taylor et al.22 shown to have 85.0% sensitivity and 89.0% specificity in identifying dementia. Because the severity of the stroke is unavailable from claims, two proxy measures were considered.23 First, inpatient length of stay categorized as ≤3 days, 4–10 days, and ≥11 days according to the variable’s distribution. Second, patient discharge status after the stroke hospitalization was grouped into four categories: “discharged to an inpatient rehabilitation facility;” “discharged home,” including home, home health, home with hospice, and left against medical advice; “discharged to SNF;” and “all other statuses” which includes long-term care hospitals, or other facilities that are not SNFs.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses of the nested cohort included frequencies and mean values, reported among those with NHP compared to those without. A Kaplan-Meier curve of the estimated survival function was calculated to compare measures of social support. We used Cox regression to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) of NHP following stroke within 1 year and 5 years from discharge, adjusting for covariates. Evidence of association was determined by an a priori α level of 0.05. Log-log plots were examined for deviations from the proportional hazards assumption. To assess the interaction effects of caregiver availability at levels of sex and income, Cox regression models were estimated with individual interactions among these variables. Evidence of interaction was determined by an a priori α level of 0.10 and further investigated through stratification. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and Stata 14 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX).

Results

Among 560 eligible participants with ischemic stroke, the average age was 77.0 (±7.1) years, 304 (54.3%) were women, 312 (55.7%) were white, 68 (12.1%) were observed to have NHP within 1 year and 119 (21.3%) within 5 years of discharge (Table 1). Those with NHP within 5 years more frequently had no available caregiver, lower income, cognitive impairment, longer hospital stays, and discharge to SNF (p<0.05). Having no available caregiver was the only statistically significant social support measure tested, with 27.6% among those with NHP lacking a caregiver compared to 16.1% who were community-dwelling (p=0.0040).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the nested cohort of participants with claims-identified ischemic stroke hospitalization.

| Cohort (n=560) | End of 5 year Follow-up

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community Dwelling (n=441) | Nursing Home (n=119) | p-value | ||

| Age at stroke, mean (SD) | 77.0 (±7.1) | 76.8 (±7.1) | 77.8 (±7.3) | 0.1635 |

| Sex | 0.3616 | |||

| Women | 304 (54.3) | 235 (53.3) | 69 (58.0) | |

| Men | 256 (45.7) | 206 (46.7) | 50 (42.0) | |

| Race | 0.1901 | |||

| White | 312 (55.7) | 252 (57.1) | 60 (50.4) | |

| Black | 248 (44.3) | 189 (42.9) | 59 (49.6) | |

| Married | 287 (51.3) | 231 (52.4) | 56 (47.1) | 0.3027 |

| Reported income at baseline | 0.0252 | |||

| ≥$50,000 year | 90 (16.1) | 78 (17.7) | 12 (10.1) | |

| $20,000 to $50,000 year | 252 (45.0) | 204 (46.3) | 48 (40.3) | |

| <$20,000 year | 138 (24.6) | 98 (22.1) | 40 (33.6) | |

| Refused to state income | 80 (14.3) | 61 (13.8) | 19 (16.0) | |

| Cognitive impairment diagnosis | 242 (43.2) | 151 (34.2) | 91 (76.5) | < .0001 |

| Stroke hospital length of stay | < .0001 | |||

| ≤3 days | 244 (43.6) | 219 (49.7) | 25 (21.0) | |

| 4–10 days | 261 (46.6) | 191 (43.3) | 70 (58.8) | |

| ≥11 days | 55 ( 9.8) | 31 ( 7.0) | 24 (20.2) | |

| Stroke hospital discharge status | < .0001 | |||

| To home | 344 (61.4) | 309 (70.1) | 35 (29.4) | |

| To inpatient rehabilitation | 88 (15.7) | 64 (14.5) | 24 (20.2) | |

| To skilled nursing facility | 107 (19.1) | 54 (12.2) | 53 (44.5) | |

| To other setting | 21 ( 3.8) | 14 ( 3.2) | 7 ( 5.9) | |

| Lives alone | 191 (34.1) | 144 (32.7) | 47 (39.5) | 0.1623 |

| Relatives “feel close to” | 0.5395 | |||

| ≤ 3 | 203 (36.3) | 165 (37.4) | 38 (31.9) | |

| 4–5 | 117 (20.9) | 90 (20.4) | 27 (22.7) | |

| ≥ 6 | 240 (42.9) | 186 (42.2) | 54 (45.4) | |

| No available caregiver | 107 (19.1) | 73 (16.6) | 34 (28.6) | 0.0031 |

Note. SD = standard deviation

p-value for t-test or χ2 test comparing those placed in a nursing home within 5 years of stroke and those community dwelling

The unadjusted risk of NHP was greater among those lacking an available caregiver, log-rank p=0.0059 (Supplemental Figure S1). After adjustment for covariates, lacking an available caregiver increased the risk of NHP following stroke within 1 year by 70% (HR1-year 1.70, 95% CI1-year 0.97–2.99) and within 5 years by 68% (HR5-year 1.68, 95% CI1-year 1.10–2.58) (Table 2). Predictors of NHP were similar across follow-up times, with some exceptions. The largest risk of NHP was discharge statuses other than home, including discharge to SNF (HR1-year 8.00, 95% CI1-year 3.89–16.46; HR5-year 4.53, 95% CI5-year 2.78–7.36) and inpatient rehabilitation (HR1-year 6.07, 95% CI1-year 2.82–13.06; HR5-year 3.36, 95% CI5-year 1.96–5.76), followed by cognitive impairment (HR1-year 2.84, 95% CI1-year 1.57–5.13; HR5-year 3.45, 95% CI5-year 2.21–5.38). Although consistent in direction and magnitude, length of hospital stay was statistically significant only within 5 years. Compared to hospital stays of ≤3 days, the risk of NHP increased for stays of 4–10 days (HR5-year 1.76, 95% CI5-year 1.09–2.85) and ≥11 days (HR5-year 2.20, 95% CI5-year 1.19–4.06).

Table 2.

Adjusted hazard ratios of factors associated with time to nursing home placement within 1 and 5 years from multivariable Cox regression (N=560).

| Hazard Ratio (1 year) | 95% Conf. Interval | Hazard Ratio (5 year) | 95% Conf. Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No caregiver available | 1.70 | 0.97–2.99 | 1.68 | 1.10–2.58 |

| Age at stroke | 0.99 | 0.96–1.03 | 0.99 | 0.96–1.02 |

| Sex | ||||

| Women | Reference | |||

| Men | 1.12 | 0.63–2.00 | 1.22 | 0.78–1.93 |

| Race | ||||

| White | Reference | |||

| Black | 1.03 | 0.62–1.70 | 1.11 | 0.76–1.63 |

| Not married (vs. currently married) | 0.97 | 0.54–1.75 | 0.90 | 0.58–1.41 |

| Reported income at baseline | ||||

| ≥$50,000 year | Reference | |||

| $20,000 to $50,000 year | 1.24 | 0.53–2.91 | 1.42 | 0.74–2.72 |

| <$20,000 year | 1.52 | 0.60–3.89 | 2.04 | 1.00–4.14 |

| Refused to state income | 0.97 | 0.34–2.79 | 1.36 | 0.63–2.96 |

| Cognitive impairment diagnosis | 2.84 | 1.57–5.13 | 3.45 | 2.21–5.38 |

| Stroke hospital stay | ||||

| ≤3 days | Reference | |||

| 4–10 days | 1.75 | 0.89–3.43 | 1.76 | 1.09–2.85 |

| ≥11 days | 1.52 | 0.63–3.70 | 2.20 | 1.19–4.06 |

| Stroke hospital discharge status | ||||

| To home | Reference | |||

| To inpatient rehabilitation | 6.07 | 2.82–13.06 | 3.36 | 1.96–5.76 |

| To skilled nursing facility | 8.00 | 3.89–16.46 | 4.53 | 2.78–7.36 |

| To other setting | 2.11 | 0.46–9.63 | 2.58 | 1.12–5.93 |

Note. Model controls for all variables listed.

Only the interaction between caregiver availability and sex (p =0.0540) was observed below our a priori threshold for further investigation of effect modification, thus excluding low income (p =0.2370). Lacking an available caregiver increased the risk of NHP among men (HR 3.15, 95% CI 1.49–6.67), but not women (HR 1.37, 95% CI 0.80–2.35; Table 3). Among men, low income (<$20,000) increased the risk of NHP compared to incomes of ≥$50,000 (HR 3.12, 95% CI 1.15–8.43). Men and women differed by the relationship to available caregiver, such that women identified a child (i.e. son or daughter) most frequently (71.6%) whereas men identified their spouse (70.5%). Comparable Cox models determined that type of caregiver was not a statistically significant predictor of NHP following stroke (available upon request).

Table 3.

Adjusted hazard ratios of factors associated with 5 year risk of nursing home placement from multivariable Cox regression stratified by sex.

| Men n=256 |

Women n=304 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Hazard Ratio | 95% Conf. Interval | Hazard Ratio | 95% Conf. Interval | |

| No caregiver available | 3.15 | 1.49–6.67 | 1.37 | 0.80–2.35 |

| Age at stroke | 0.99 | 0.95–1.03 | 1.00 | 0.97–1.04 |

| Race | ||||

| White | Reference | |||

| Black | 0.94 | 0.49–1.82 | 1.25 | 0.76–2.06 |

| Not married (vs. currently married) | 0.70 | 0.32–1.54 | 0.96 | 0.54–1.73 |

| Reported income at baseline | ||||

| ≥$50,000 year | Reference | |||

| $20,000 to $50,000 year | 1.46 | 0.63–3.39 | 0.97 | 0.32–2.91 |

| <$20,000 year | 3.12 | 1.15–8.43 | 1.01 | 0.33–3.11 |

| Refused to state income | 2.40 | 0.84–6.85 | 0.68 | 0.21–2.26 |

| Cognitive impairment diagnosis | 6.56 | 2.95–14.60 | 2.73 | 1.55–4.80 |

| Stroke hospital stay | ||||

| ≤3 days | Reference | |||

| 4–10 days | 2.14 | 0.96–4.80 | 1.58 | 0.86–2.92 |

| ≥11 days | 2.68 | 0.95–7.58 | 1.89 | 0.87–4.07 |

| Stroke hospital discharge status | ||||

| To home | Reference | |||

| To inpatient rehabilitation | 2.36 | 0.87–6.43 | 4.25 | 2.15–8.39 |

| To skilled nursing facility | 5.51 | 2.66–11.41 | 4.31 | 2.18–8.52 |

| To other setting | 3.05 | 0.62–15.03 | 2.43 | 0.88–6.72 |

Note. Model controls for all variables listed.

Discussion

Our study finds men aged 65 years and older, who could not identify a potentially available caregiver prior to having a stroke, had greater risk of NHP following stroke than men with a caregiver. This was the only social support measure tested with a statistically significant effect, and thus a stronger predictor of NHP than marital status, living alone, and having relatives or close friends. Although the lack of a caregiver was statistically significant in the full sample, the risk of NHP was non-uniform; we observed the effect statistically significant only in men.

Our findings are consistent with previous research. Older adults with higher levels of social support, including the availability of a caregiver, have been shown to have better outcomes following stroke and have lower risk of institutionalization.5,21,24–30 Lacking a caregiver is known to be more common among men.31 However, men are also less likely to use formal services.32,33 For many men, it is often assumed their spouse can serve as a caregiver (approximately 71% within the REGARDS cohort).11,34 Perceptions of caregiver availability are different between men and women, such that older women may ignore some factors in judging the availability of potential caregivers.11,35 Although women more often act as caregivers, the effect of having a caregiver appears less important compared to men. Women are generally less reliant on spouses for caregiving than men and better connected to non-spousal caregivers, which may explain the difference in NHP risk compared to men.11

Counter to previous research, we observed no association between marital status, living along, or feeling close to relatives and the risk of NHP following stroke. While these variables are proxy measures of having social support or a potential caregiver, our analysis measured caregiver availability directly and thus was less ambiguous. Our findings, which are specific to men, could be influenced by differences in how men and women estimate the ability of a family member or spouse to take on the role of caregiver—perceiving they do not have a caregiver when they do, or vice versa. Although we observed no effects specific to the available caregiver’s relation and NHP, there are likely additional familial dynamics predisposing men lacking caregivers to have increased risk of NHP, such divorce or the sexes of their children, that warrant further investigation.

We also observed low income men had an increased risk of NHP. Low income status likely coincides with the inability to pay for formal services and is highly correlated with Medicaid eligibility. Our measure of income was taken prior to stroke, and therefore is not a reflection of spend down or destitution resulting from the institutionalization.36 For low income men without caregivers, NHP may be the only option. It is unclear how home and community-based services (HCBS), specifically Medicaid waiver programs, impact this population. Data were not available to assess use of HCBS within REGARDS. Future research may be able to elucidate whether HCBS can delay NHP for older men with low income who lack caregivers. As the aging U.S. population becomes less reliant on unpaid caregiving and increasingly uses paid caregiving, expanding the capacity of HCBS and understanding long-term outcomes will be critical.37–39

Some important strengths of our study are the use of a population-based prospective cohort study linked to Medicare claims. Despite these strengths, our study should be interpreted in light of some limitations. Social support measures, including caregiver availability, were assessed in REGARDS during baseline interviews but any changes over time were not captured and thus could not be analyzed as time-dependent variables. We believe it more common to lose potential caregivers rather than gain, resulting in bias towards the null. We investigated single item measures of social support, and thus our findings may not represent index measures incorporating multiple items. No measure of stroke severity is available in Medicare claims, nor do we know specifically what precipitated NHP. Likewise, we did not have information regarding functional limitations which are associated with nursing home placement. Our cohort consisted of only community-dwelling participants and we included hospital length of stay and discharge status as proxy measures of stroke severity, however we acknowledge this is inferior to formal measurement.23 Our claims-based algorithm to identify stroke may be subject to misclassification. In an effort to determine how this may have impacted our findings, a sensitivity analysis was conducted using strokes identified by the REGARDS study team and adjudicated by an expert panel of clinicians. We found that 95% of our sample was in agreement as an ischemic stroke; however, 50% of claims-based strokes were not reviewed by the REGARDS team. Reasons include medical records were unavailable, coding errors, diagnoses not indicative of an incident stroke. Nonetheless, replicating our main analysis among 282 strokes identified with both methods estimated qualitatively similar results—HR5-year for available caregiver was 2.69 (95% CI5-year 1.33–5.44)—bolstering the robustness of our findings in the claims-only sample. While our income measure represents income at baseline when the participant was community-dwelling and prior to their stroke, we could not assess the relationship to wealth, such as owning a home or net worth, which are important factors in determining future Medicaid eligibility for long-term care. Our stratified analysis reduced the sample size considerably. This limited our ability to further explore important subgroups. Finally, our sample was limited to REGARDS participants who were Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older with fee for service coverage and may not generalize to younger populations or those with managed plans.

Conclusion

Following a stroke, men who lack a caregiver have a greater risk of NHP than men with a caregiver. Our findings suggest clinicians remain cognizant of the important role caregivers play for older adults to remain independent, in particular those most vulnerable including men lacking caregivers. Opportunities exist for clinicians to educate and counsel families on the expectations of care needs and caregiving following stroke, as well as recognize the need for formal services and assist in aligning patients with resources. Future research efforts should focus on how long-term care policies, in particular those pertaining to HCBS, can mitigate the risk of NHP following stroke. Moreover, identifying the specific needs of individuals that require NHP, namely men, and the deficiencies of caregivers will enable better alignment of services to permit continued community residence where appropriate and desired. Although beyond the scope of our current analysis, a better understanding is needed comparing additional outcomes, including quality of life, among individuals who have caregivers compared with those who enter nursing homes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: The REGARDS research project is supported by a cooperative agreement from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; the National Institutes of Health; and the Department of Health and Human Services (U01 NS041588). Additional support was provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K12 HS023009) to [J.B.]; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K24 HL111154) to [M.M.S.], and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01 NS075047) to [W.E.H, D.L.R., and M.L.K.].

The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the REGARDS study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating REGARDS investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.regardsstudy.org.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this work.

Author Contributions: Design and conceptualization of the study: Albright, Blackburn, Howard, Kilgore, Safford. Statistical analysis: Blackburn. Interpretation of data: Haley, Howard, Roth, Kilgore. Drafting and revision of the manuscript: Blackburn, Albright, Howard, Kilgore. Critical review of the manuscript: Haley, Roth, Safford. All authors, and the REGARDS Executive Committee, approved the final version of the manuscript.

Sponsor’s Role: The funding agencies had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Gaugler JE, Duval S, Anderson KA, et al. Predicting nursing home admission in the U.S.: a meta-analysis. BMC Geriatrics. 2007;7:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buntin MB, Colla CH, Deb P, et al. Medicare spending and outcomes after post-acute care for stroke and hip fracture. Med Care. 2010;48:776–784. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e359df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly-Hayes M, Beiser A, Kase CS, et al. The influence of gender and age on disability following ischemic stroke: the Framingham study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;12:119–126. doi: 10.1016/S1052-3057(03)00042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lackland DT, Roccella EJ, Deutsch AF, et al. Factors influencing the decline in stroke mortality a statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:315–353. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000437068.30550.cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell CL, LaCroix AZ, Desai M, et al. Factors associated with nursing home admission after stroke in older women. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24:2329–2337. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reeves MJ, Bushnell CD, Howard G, et al. Sex differences in stroke: epidemiology, clinical presentation, medical care, and outcomes. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:915–926. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70193-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petrea RE, Beiser AS, Seshadri S, et al. Gender differences in stroke incidence and poststroke disability in the Framingham heart study. Stroke. 2009;40:1032–1037. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.542894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller N, Harrington C, Goldstein E. Access to community-based long-term care: Medicaid’s role. J Aging Health. 2002;14:139–159. doi: 10.1177/089826430201400108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiener JM, Khatutsky G, Thach N, et al. Findings from the survey of long-term care awareness and planning. [Accessed November 16, 2016];ASPE Issue Brief. 2015 Jul; URL: https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/110366/SLTCAPrb.pdf.

- 10.Charles KK, Sevak P. Can family caregiving substitute for nursing home care? J Health Econ. 2005;24:1174–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roth DL, Haley WE, Wadley VG, et al. Race and Gender Differences in Perceived Caregiver Availability for Community-Dwelling Middle-Aged and Older Adults. Gerontologist. 2007;47:721–729. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.6.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hagen S. Rising demand for long-term services and supports for elderly people. Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office; 2013. Jun, [Accessed November 16, 2016]. URL: https://www.cbo.gov/publication/44363. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levine C, Halper D, Peist A, et al. Bridging troubled waters: family caregivers, transitions, and long-term care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:116–124. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stone R, Harahan MF. Improving the long-term care workforce serving older adults. Health Aff(Millwood) 2010;29(1):109–115. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howard G, Anderson R, Johnson NJ, et al. Evaluation of social status as a contributing factor to the stroke belt region of the United States. Stroke. 1997;28:936–940. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.5.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howard VJ, Cushman M, Pulley L, et al. The Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke Study: Objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25:135–143S. doi: 10.1159/000086678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie F, Colantonio LD, Curtis JR, et al. Linkage of a population-based cohort with primary data collection to Medicare claims: the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;184:532–544. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumamaru H, Judd SE, Curtis JR, et al. Validity of claims-based stroke algorithms in contemporary Medicare data: REGARDS study linked with Medicare claims. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7:611–619. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lakshminarayan K, Larson JC, Virnig B, et al. Comparison of Medicare claims versus physician adjudication for identifying stroke outcomes in the Women’s Health Initiative. Stroke. 2014;45:815–821. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yun H, Kilgore ML, Curtis JR, et al. Identifying types of nursing facility stays using Medicare claims data: an algorithm and validation. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol. 2010;10:100–110. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luppa M, Luck T, Weyerer S, et al. Prediction of institutionalization in the elderly. A systematic review. Age Ageing. 2010;39:31–38. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor DH, Jr, Ostbye T, Langa KM, et al. The accuracy of Medicare claims as an epidemiological tool: the case for dementia revisited. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17:807–815. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qureshi AI, Chaudhry SA, Sapkota BL, et al. Discharge destination as a surrogate for Modified Rankin Scale defined outcomes at 3- and 12-months poststroke among stroke survivors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:1408–1413. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andel R, Hyer K, Slack A. Risk factors for nursing home placement in older adults with and without dementia. J Aging Health. 2007;19:213–228. doi: 10.1177/0898264307299359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bharucha AJ, Pandav R, Shen C, et al. Predictors of nursing facility admission: a 12-year epidemiological study in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:434–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kasper JD, Pezzin LE, Rice JB. Stability and changes in living arrangements: relationship to nursing home admission and timing of placement. J Geron Soc Sci. 2010;65B:783–791. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller EA, Weissert WG. Predicting elderly people’s risk for nursing home placement, hospitalization, functional impairment, and mortality: a synthesis. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57:259–297. doi: 10.1177/107755870005700301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roth DL, Sheehan OC, Huang J, et al. Medicare claims indicators of healthcare utilization differences after hospitalization for ischemic stroke: race, gender, and caregiving effects. Int J Stroke. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1747493016660095. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wattmo C, Wallin AK, Londos E, et al. Risk factors for nursing home placement in Alzheimer’s disease: a longitudinal study of cognition, ADL, service utilization, and cholinesterase inhibitor treatment. Gerontologist. 2011;51:17–27. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freedman VA, Berkman LF, Rapp SR, et al. Family networks: predictors of nursing home entry. AJPH. 1994;84:843–845. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.5.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Talamantes MA, Cornell J, Espino DV, et al. SES and ethnic differences in perceived caregiver availability among young-old Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic Whites. Gerontologist. 1996;36:88–99. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones AL, Harris-Kojetin L, Valverde R. National health statistics reports. 52. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. Characteristics and use of home health care by men and women aged 65 and over. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kadushin G. Home health care utilization: a review of the research for social work. Health Soc Work. 2004;29:219–244. doi: 10.1093/hsw/29.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Ethnic differences in stressors, resources, and psychological outcomes of family caregiving: A meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2005;45:90–106. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pillemer K, Suitor JJ. Making choices: A within-family study of caregiver selection. Gerontologist. 2006;46:439–448. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tajeu GS, Delzell E, Smith W, et al. Death, debility, and destitution following hip fracture. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69:346–353. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ankuda CK, Levine DA. Trends in caregiving assistance for home-dwelling, functionally impaired older adults in the United States, 1998–2012. JAMA. 2016;316:218–220. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spillman BC, Pezzin LE. Potential and active family caregivers: changing networks and the “sandwich generation”. Millbank Q. 2000;78:347–374. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolff JL, Kasper JD. Caregivers of frail elders: updating a national profile. Gerontologist. 2006;46:344–356. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.