Abstract

Background/Objectives

It is unknown whether cerebral blood flow (CBF) may be altered in individuals with type 2 diabetes by a long-term behavioral intervention targeting weight loss through increased physical activity and reduced caloric intake.

Design

Post-randomization assessment of cerebral blood flow

Setting

Multicenter randomized controlled clinical trial

Participants

At enrollment in the Action for Health in Diabetes clinical trial, participants (N=310) had Type 2 diabetes and were overweight or obese and aged 45–76 years.

Interventions

A multidomain intensive Lifestyle Intervention (ILI) for 8–11 years to induce weight loss and increase physical activity or Diabetes Support and Education (DSE), a control condition

Measurements

Participants underwent cognitive assessment and standardized brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (3.0 Tesla) to assess CBF an average of 10.4 years after randomization.

Results

Weight changes from baseline to time of MRI averaged −6.2% for ILI versus −2.8% for DSE (p<0.001), and increases in self-reported moderate or intense physical activity averaged 444.3 kilocalories/week versus 114.8 kilocalories/week (p=0.03). Overall mean CBF was 6% greater among ILI compared with DSE (p=0.037), with the largest mean [95% confidence interval] differences between ILI and DSE in the limbic region and occipital lobes of 3.39 [0.07,6.70] and 3.52 [0.20,6.84] ml/100g/min, respectively. In ILI, greater CBF was associated with greater decreases in weight and greater increases in physical activity. The relationship between CBF and individuals’ scores on a composite measure of cognitive function varied between intervention groups (p=0.016).

Conclusions

Long-term weight loss intervention in overweight and obese adults with Type 2 diabetes is associated with greater CBF.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Intensive lifestyle intervention, Obesity, Cerebral blood flow

INTRODUCTION

Type 2 diabetes may impair cerebral blood flow (CBF) through mechanisms related to increased vessel stiffness, reduced vascular function, and lumen narrowing.1 Obesity is also associated with decreased CBF.2–3 Impaired CBF is linked to poorer cognitive function and cognitive decline among individuals with insulin resistance and diabetes.1,4 It is also a marker for microvascular disease in the brain and other vascular beds.5,6

Because of its relationship with obesity and evidence that it may be increased with greater levels of physical activity,7 it is reasonable to hypothesize that CBF may be enhanced by behavioral intervention targeting weight loss through increased physical activity and reduced caloric intake. The Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) was a multi-center randomized controlled clinical trial that featured 10 years of such a multidomain intervention, which successfully induced long-term behavioral changes.8,9 The Look AHEAD Brain MRI Study leveraged this resource and included the goal of assessing whether random assignment to long-term behavioral intervention had a legacy of improved CBF among older adults with type 2 diabetes.

Look AHEAD has previously reported that its intensive lifestyle intervention improved markers of cerebrovascular disease and brain atrophy.10 Signals have been mixed for cognitive function, with evidence that the intervention benefited cognitive function for participants whose BMI was initially 25–29 kg/m2, but lowered cognitive function among heavier participants11,12 We examined CBF data to gain a deeper understanding of the effects of the lifestyle intervention on brain health.

METHODS

The Look AHEAD design, methods, and CONSORT diagram have been published previously.8,13 It was a single-blinded RCT that recruited 5,145 individuals (during 2001 to 2004) who were overweight or obese and had type 2 diabetes. At enrollment, participants were 45–76 years of age with body mass index (BMI) >25 kg/m2 (>27 kg/m2 if on insulin), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) <11%, systolic/diastolic blood pressure <160/<100 mmHg, and triglycerides <600 mg/dl.

Interventions

Participants were randomly assigned with equal probability to a multidomain Intensive Lifestyle Intervention (ILI) or a Diabetes Support and Education (DSE) control condition. Interventions were terminated in September, 2012.13

The ILI included diet modification and physical activity, designed to induce and maintain an average weight loss ≥ 7%.14 ILI participants were assigned a daily calorie goal (1200–1800 based on initial weight), with <30% of total calories from fat (<10% from saturated fat) and a minimum of 15% of total calories from protein. The physical activity goal was >175 minutes of physical activity per week through activities similar in intensity to brisk walking. They were seen weekly for the first 6 months and 3 times per month for the next 6 months, with a combination of group and individual contacts. During years 2–4, they were seen individually at least once a month, contacted another time each month by phone or e-mail, and offered a variety of centrally-approved group classes. After this, ILI participants were encouraged to continue individual monthly sessions and annual campaigns were used to promote maintenance of weight loss.

Participants in DSE were invited to attend three group sessions each year, which featured standardized protocols with focus on diet, physical activity, and social support. They did not receive specific diet, activity, or weight goals.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

The Look AHEAD Brain MRI study enrolled Look AHEAD participants at three clinics to assess brain structure and function at either their 10-, 11-, or 12-year anniversary from Look AHEAD enrollment. Only those for whom MRI was safe and who provided separate informed consent were eligible. The protocol and consent forms were approved by local Institutional Review Boards.

The three clinics had originally enrolled 1,008 participants into Look AHEAD. When the MRI study began, five had withdrawn from Look AHEAD, 89 had died, 20 had refused further follow-up, and 19 were lost to follow-up, leaving a potential of 875 recruits. Of these, 321 (37%) agreed to participate, were eligible for the study, and completed the MRI; 310 (97%) images met CBF quality control standards.

Prior to MRI, participants were screened for contra-indications and instructed to remove all metal objects. Measures of brain structure (overall and region-specific total and white matter hyperintensity volumes) were obtained according to standard protocols following training and quality control measures administered by the MRI Reading Center at the University of Pennsylvania.10 CBF was assessed with multi-phase pseudo Continuous Arterial Spin Labeling (pCASL) with background suppression for labeling the endogenous blood water.15,16 Multi-phase pCASL has a 50% improvement over pulsed ASL methods, does not require special RF coils and RF amplifiers, and is less susceptible to magnetic field inhomogeneity at the labeling plane. Parameters for the multi-phase pCASL were: tag duration=1600ms, post labeling delay=1000ms, tag TR=1.2ms, and phases=−90, 0, 90, and 180. Background suppression was achieved with selective saturation pulses immediately before the pCASL preparation sequence followed by adiabatic inversion pulses.17 Images were acquired with single-shot 3D GRASE, which has been shown to improve the signal-to-noise ratio by 300% compared to images acquired with 2D echo-planar imaging (EPI). We analyzed CBF totals17 (both white and gray matter) from five non-overlapping regions of interest: the frontal, occipital, parietal, and temporal lobes and the limbic region.

Cognitive function

Standardized cognitive function assessments were performed by centrally trained and certified staff, masked to intervention assignment.11 Verbal learning and memory were assessed with the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, speed of processing and working memory were assessed with the Digit Symbol Coding test, executive functions were assessed with the Modified Stroop Color and Word Test (MSCWT) and the Trail Making Test-Part B and global cognitive functioning was assessed by the Modified Mini-Mental Status exam. Tests were administered an average of 19 days from the date of the MRI.

Other measures

At Look AHEAD enrollment, self-reported characteristics and conditions were assessed using standardized questionnaires. Prescription medications were brought to clinics for verification. Blood pressure was measured in duplicate using a Dinamap Monitor Pro 100 automated device. Hypertension was based on measured blood pressure >140/90 mmHg or current pharmacological treatment. Blood specimens were collected after at least a 12-hour fast and analyzed centrally. History of cardiovascular disease was defined by self-report of prior myocardial infarction, stroke, coronary or lower extremity angioplasty, carotid endarterectomy, or coronary bypass surgery.

Annual measures of weight were obtained throughout follow-up and physical activity was reported at baseline and years 1, 4 and 8 using the Paffenbarger questionnaire to estimate kilocalories per week of moderate or intense physical activity.8

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of baseline characteristics between participants included in our analyses with those of others, and between intervention groups, were based on chi-squared and t-tests. The primary outcome was the mean CBF across the five brain regions. Mixed effects models were used to compare this mean between intervention groups while controlling for inter-regional correlations. Covariate adjustment was made for current age, sex, education, race/ethnicity, clinic, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Because blood pressure was not measured at the time of MRI, we used values from both the most recent prior exam and the exam following the MRI. These did not vary significantly between intervention groups. Cognitive function test scores were standardized by subtracting the overall mean and dividing this difference by their standard deviation to allow for comparisons among different tests, and ordered so that positive scores reflected better performance.11 A composite score was formed by averaging the individual standardized scores, and renormalizing this to have standard deviation of 1.

RESULTS

Table 1 describes participants at Look AHEAD enrollment. The balance afforded by the original randomization was largely preserved in this subset of participants, with slightly greater prevalence of higher BMI levels among the DSE compared with ILI participants (p=0.03).

Table 1.

Characteristics at the time of enrollment into the Look AHEAD trial: mean (standard deviation) or N (percent).

| DSE N=153 |

ILI N=157 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age | 57.5 (6.3) | 58.5 (6.6) | 0.18 |

|

| |||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 112 (73.2) | 104 (66.2) | 0.18 |

| Male | 41 (26.8) | 53 (33.8) | |

|

| |||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| African-American | 36 (23.5) | 31 (19.8) | 0.71 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 109 (71.2) | 118 (75.2) | |

| Other, Multiple | 8 (5.2) | 8 (5.1) | |

|

| |||

| Education | |||

| High School | 23 (15.0) | 29 (18.5) | |

| College Graduate | 58 (37.9) | 53 (33.1) | 0.65 |

| Post College | 66 (43.1) | 72 (45.9) | |

| Other | 6 (2.9) | 4 (2.6) | |

|

| |||

| BMI, kg/m2 | |||

| 25–29 | 18 (11.8) | 32 (20.4) | 0.03 |

| 30–39 | 99 (64.7) | 102 (65.0) | |

| ≥40 | 36 (23.5) | 23 (14.6) | |

|

| |||

| Smoking | |||

| Never | 75 (49.0) | 81 (51.6) | |

| Former | 72 (47.1) | 70 (44.6) | 0.90 |

| Current | 6 (3.9) | 6 (3.8) | |

|

| |||

| Hypertension | 128 (83.7%) | 129 (82.2%) | 0.73 |

|

| |||

| Blood pressure, mmHg | |||

| Systolic | 130.4 (17.1) | 127.7 (16.4) | 0.16 |

| Diastolic | 69.9 (9.6) | 70.0 (10.2) | 0.89 |

|

| |||

| Insulin use | 20 (13.1) | 16 (10.2) | 0.43 |

|

| |||

| Diabetes Duration, Miss=6 | |||

| <5 years | 72 (47.7) | 74 (48.4) | 0.73 |

| ≥5 years | 79 (52.3) | 79 (51.6) | |

|

| |||

| HbA1c, % | 7.39 (1.36) | 7.27 (1.09) | 0.38 |

|

| |||

| History of CVD | 13 (8.5) | 13 (8.3) | 0.95 |

The average (± standard deviation) time between randomization and MRI was 10.4 (±0.5) years for both ILI and DSE participants (p=0.87). The average time between the end of the intervention and the time of MRI was 0.6±0.7 years for ILI and 0.5±0.8 years for DSE (p=0.19) participants. MRIs were collected on 27% of ILI and 34% of DSE participants prior to the termination of the intervention (p=0.20), with the remainder collected after its termination.

Supplemental Table 1 summarizes BMI and physical activity levels over time. Listed are mean levels at Look AHEAD baseline, mean changes from baseline averaged across all follow-up assessments prior to the MRI, and mean changes from baseline to the most proximal assessment preceding the MRI. At baseline, mean (standard error) BMI was slightly higher among DSE compared with ILI participants: 36.25 (0.47) versus 34.76 (0.42), p=0.01. Baseline physical activity levels were similar between groups (p=0.35). Mean changes in BMI from baseline over time were −2.84 (0.57) kg/m2 for DSE participants and −6.22 (0.52) kg/m2 for ILI participants (p<0.001). Mean changes in self-reported kilocalories per week of moderate or intensive physical activity over time were 114.8 (102.2) kilocalories/week for DSE participants and 444.3 (108.0) kilocalories/week for ILI participants (p=0.03). However, at the assessment most proximal prior to the MRI, group differences in BMI and physical activity changes were no longer statistically significant.

Table 2 portrays covariate-adjusted mean CBF, overall (primary outcome) and for five individual brain regions. Total brain CBF levels were higher among ILI compared with DSE participants (p=0.037). Across all regions, mean CBF levels were 6–7% greater among ILI compared with DSE participants; inter-regional differences between groups were minor (interaction p=0.950).

Table 2.

Mean cerebral blood flow by intervention assignment, with covariate adjustment for clinic, regional volume, age at MRI, gender, race/ethnicity, baseline BMI, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Comparison between intervention groups from mixed effects model: p=0.037. Heterogeneity among regions: p=0.95.

| Region | Mean (SE) Cerebral Blood Flow (ml/100g/min) | Mean Difference: ILI Minus DSE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSE | ILI | Mean(SE) | 95% CI | |

| Overall Mean | 48.61 (1.54) | 51.60 (1.50) | 2.99 (1.43) | [0.38,5.81]a |

| Frontal lobe | 42.59 (3.21) | 45.20 (3.22) | 2.61 (1.69) | [−0.71,5.92] |

| Limbic region | 54.65 (2.66) | 58.04 (2.67) | 3.39 (1.69) | [0.07,6.70]a |

| Occipital lobe | 53.54 (1.54) | 57.06 (1.53) | 3.52 (1.69) | [0.20,6.84]a |

| Parietal lobe | 47.91 (1.19) | 50.71 (1.17) | 2.80 (1.69) | [−0.51,6.12] |

| Temporal lobe | 44.33 (1.26) | 46.99 (1.25) | 2.65 (1.69) | [−0.66,5.97] |

Confidence interval excludes 0

Table 3 summarizes associations that changes in weight and physical activity levels over time had with total brain CBF within intervention groups, using 95% confidence intervals to assess within group relationships and tests of interaction to assess whether relationships vary between intervention groups. To facilitate comparisons among measures, slopes were standardized to be reported as CBF per baseline standard deviation of the predictor measure. Average percent weight change had little association with total brain CBF among DSE participants: the 95% confidence interval for the slope squarely overlapped 0. Among ILI participants, greater weight loss was related to greater CBF (95% confidence interval excludes 0), however, a test of interaction comparing slopes did not reach statistical significance (p=0.131). A similar pattern was seen for physical activity, which was last assessed 1–3 years prior to the MRI. In the DSE group, there was no association between changes in physical activity and CBF. In the ILI group, greater increases in physical activity were associated with greater CBF among ILI participants, however again differences in slopes did not reach statistical significance (p=0.102).

Table 3.

Relationships that total brain cerebral blood flow has with changes in weight and physical activity and cognitive function (positive scores reflect better performance), with covariate adjustment for current age, sex, education, race/ethnicity, clinic, blood pressure, baseline value, and total brain volume.

| Relationship with Total Brain Cerebral Blood Flow: Slope (SE): (ml/100g/min) / (Standard deviation) | 95% Confidence Interval | Interaction p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Average Change from Baseline | |||

| Weight (Percent Change) | |||

| DSE | −0.259 (0.781) | [−2.315,1.398] | 0.131 |

| ILI | −2.525 (1.097) | [−4.686, −0.364]a | |

| Physical Activity (kcal/week) | |||

| DSE | 0.502 (1.218) | [−1.903,2.904] | 0.102 |

| ILI | 3.288 (1.171) | [0.978,5.597]a | |

|

| |||

| Cognitive Function | |||

| Modified MiniMental State | |||

| DSE | −1.805 (1.207) | [−4.180,0.157] | 0.160 |

| ILI | 0.472 (1.166) | [−1.824,2.767] | |

| Digit Symbol Coding Test | |||

| DSE | −1.669 (1.075) | [−3.785,0.446] | 0.038 |

| ILI | 1.362 (1.153) | [−0.098,3.623] | |

| Stroop MSCWT | |||

| DSE | −2.091 (1.110) | [−4.275,0.094] | 0.013 |

| ILI | 1.474 (0.993) | [−0.480,3.429] | |

| Trail Making – B** | |||

| DSE | −2.757 (1.039) | [−4.801, −0.713]a | 0.040 |

| ILI | 0.120 (1.100) | [−2.044,2.285] | |

| Rey Auditory Verbal Learning | |||

| DSE | −0.476 (1.057) | [−2.557,1.604] | 0.323 |

| ILI | 0.949(1.052) | [−1.121,3.019] | |

| Composite | |||

| DSE | −2.256 (1.076) | [−4.375, −0.137]a | 0.016 |

| ILI | 1.188 (1.142) | [−1.059,3.435] | |

Confidnce interval excludes 0

Associations between cognitive function scores and CBF are also summarized in Table 3. Among DSE participants, poorer scores were associated with greater CBF, consistently across tests. Among ILI participants, there was not a significant association between test scores and CBF. Differences in the associations between scores and CBF between intervention groups were statistically significant (p<0.05) for three tests (digit symbol coding, Stroop MSCWT, and Trail Making-B) and for the composite from all five scores.

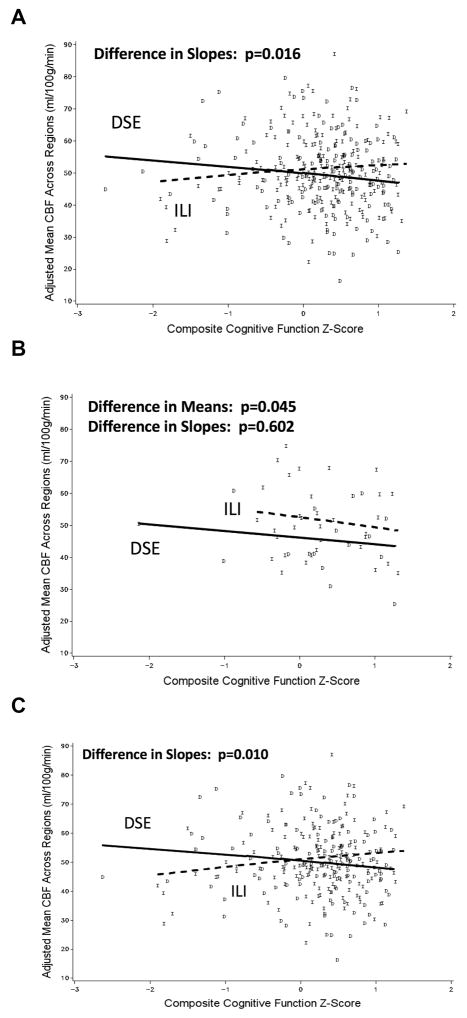

Among DSE participants, greater CBF was associated with poorer cognitive function scores overall, but not among ILI participants (Figure 1a; p=0.016). Similar patterns were seen in each of the five individual brain regions. We examined how CBF was associated with cognitive function in subgroups of participants based on their BMI at Look AHEAD baseline: 25–29 kg/m2 (overweight participants, Figure 1b) and ≥ 30 kg/m2 (obese participants, Figure 1c). For participants initially overweight, CBF tended to be greater among those assigned to ILI compared with DSE (p=0.045). In this subgroup, the slopes between cognitive function and CBF were similar in both the ILI and DSE groups (p=0.602). For participants initially obese, the slopes linking CBF to cognitive function varied between the ILI and DSE groups (p=0.010): there was a trend for a negative association within the DSE group and a positive association among ILI participants.

Figure 1.

Relationships that composite cognitive function has with average cerebral blood flow across five brain regions (adjusted for current age, sex, education, race/ethnicity, clinic, blood pressure, and average regional volume): (a) overall; (b) baseline BMI<30 kg/m2; (c) baseline BMI>30 kg/m2.

DISCUSSION

Maintaining appropriate CBF is necessary for normal brain functioning. This involves a complex interplay of systems for vascular responses (i.e. vasodilation and vasoconstriction) that are necessary to avoid both hypo- and hyper-perfusion.18 It also involves angiogenesis, in which the vascular network is extended in response to injury and increased metabolic requirements.19,20 While relatively lower CBF may reflect poorer circulation due to cerebrovascular disease, higher CBF may be a response to greater metabolic demands,6 perhaps resulting from less efficient cognitive function. This complex relationship may explain why some have found no relationship between CBF and cognitive function among individuals with diabetes.21

Our analyses of CBF data spanning the termination of the Look AHEAD interventions yield three principal findings. First, there was evidence that the 10-year intensive lifestyle intervention, compared with the control condition, had a legacy of about a 6% greater CBF across brain regions. Within the intervention group, CBF was correlated with changes in weight and physical activity over time; these relationships were not evident within the control group. Second, within the control group, there was an inverse association between cognitive function test scores and CBF: higher CBF was found among those with poorer levels of performance. Third, within the intervention group, there appeared to be little or no association between cognitive performance and CBF, however there was some evidence that this finding varied depending on participant’s initial obesity status.

Lifestyle intervention and CBF

Observational and limited clinical trial data link greater levels of physical activity to greater CBF, however this association may wane with age.22,23 While obesity is associated with lower CBF in diabetes,24 there is little literature linking weight loss through behavioral intervention to changes in CBF. Ours is the first report that, overall, long-term lifestyle intervention is associated with greater CBF. We see this as a benefit, which is consistent with earlier reports from Look AHEAD that its intervention was associated with less cerebrovascular disease (white matter hyperintensity volumes) and better profiles of nephropathy and neuropathy (both associated with fewer microvascular complications).10,25,26 It is also consistent with beneficial effects that Look AHEAD has reported on risk factors for vascular disease, including blood pressure, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, and markers of inflammation.9,27

CBF and cognitive function within the control group

Overall, DSE participants had relatively lower CBF compared with ILI participants. However, within this control group, greater CBF was associated with lower cognitive performance. This may appear counterintuitive. One possible explanation is that this reflects an adaptive response to increased metabolic requirements related to decreased cognitive efficiency, either through vascular dilation or angiogenesis,18,28 however we have no data to support this speculation.

CBF and cognitive function within the intervention group

In contrast to DSE participants, there appeared to be no overall association between CBF and cognitive function among ILI participants. It is possible that this is linked to a blunted neurovascular response to decreases in cognitive efficiency and neurodegeneration. Possible explanations include weight loss-induced alterations in apelin and leptin levels,29,30 hormones that may promote angiogenesis and vasodilation,31–34 or decreases in cardiac output, which may lead to lower CBF independently of blood pressure.35

Differences in relationships depending on baseline BMI

As noted in the introduction, there were significant interactions between the ILI effects on cognitive function and cognitive impairment depending on initial obesity status. When delivered to individuals with BMI<30 kg/m2, ILI was associated with better cognitive function and less cognitive impairment; when delivered to heavier individuals, ILI was associated with poorer cognitive function.

CBF data may contribute to our understanding of the interaction. For individuals with initial BMI <30 kg/m2, associations between CBF and cognitive function were quite different than those for heavier participants. For non-obese ILI participants, and for both non-obese and obese DSE participants, associations were consistent with the hypothesis for neurovascular response related to cognitive deficits. For obese ILI participants, however, who achieved greater overall weight losses than non-obese participants,36 CBF data provide no evidence for such a neurovascular response.

Limitations

Our study is strengthened by the original randomization, standardization, long-term adherence, and rich characterization. However, no assessments of brain MRI or cognitive function were obtained at baseline and, as comprised of volunteers for a clinical trial, the cohort may not resemble general clinic populations. While there is no available evidence that the enrollment in the MRI study was differential by intervention,10 unmeasured confounders may have influenced findings. It follows that our findings should be viewed as exploratory and hypothesis-generating.

Summary

Long-term behavioral intervention for weight loss in type 2 diabetes may result in greater overall greater CBF. However, among obese individuals, weight loss may impair neurovascular responses to increase CBF among individuals with lower cognitive function. This finding is consistent with data from Look AHEAD, that while cognitive function may be improved by behavioral intervention among individuals who are overweight, it results in relative decrements in cognitive function and increased prevalence of cognitive impairment among obese individuals with type 2 diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Table 1: Body mass index and self-reported physical activity at baseline and changes from baseline.

Impact Statement.

We certify that this work is novel.

-

The potential impact of this research on clinical care or health policy includes the following:

It adds support for multidomain intensive lifestyle intervention to be recommended for the treatment of adults with Type 2 diabetes to promote better brain health later in life.

It generates hypotheses for further study of neurovascular responses to cognitive deficits in type 2 diabetes and how intensive lifestyle intervention may alter these in obese individuals.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: The Look AHEAD Brain MRI ancillary study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services: DK092237-01 and DK092237-02S2. The Action for Health in Diabetes is supported through the following cooperative agreements from the National Institutes of Health: DK57136, DK57149, DK56990, DK57177, DK57171, DK57151, DK57182, DK57131, DK57002, DK57078, DK57154, DK57178, DK57219, DK57008, DK57135, and DK56992. The following federal agencies have contributed support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Nursing Research; National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities; Office of Research on Women’s Health; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and the Department of Veterans Affairs. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The Indian Health Service (I.H.S.) provided personnel, medical oversight, and use of facilities. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the I.H.S. or other funding sources.

Additional support was received from the University of Pittsburgh General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) (M01RR000056), the Clinical Translational Research Center (CTRC) funded by the Clinical & Translational Science Award (UL1 RR 024153) and NIH grant (DK 046204); Frederic C. Bartter General Clinical Research Center (M01RR01346); and the Wake Forest Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center (P30AG049638-01A1).

The following organizations have committed to make major contributions to Look AHEAD: FedEx Corporation; Health Management Resources; LifeScan, Inc., a Johnson & Johnson Company; OPTIFAST® of Nestle HealthCare Nutrition, Inc.; Hoffmann-La Roche Inc.; Abbott Nutrition; and Slim-Fast Brand of Unilever North America.

Clinical Sites

-

University of Pennsylvania

Thomas A. Wadden1; Barbara J. Maschak-Carey2; Robert I. Berkowitz3; Bernadette Bailey; Yuliis Bell; Norman Butler; Raymond Carvajal; Christos Davatzikos; Renee Davenport; Lisa Diewald; Mark Elliott; Lucy Faulconbridge; Barry Fields; Krista Huff; Mary Jones-Parker; Brendan Keenan; Sharon Leonard; Qing-Yun Li; Katelyn Reilly; Kelly Sexton; Bethany Staley; Matthew Voluck

-

University of Pittsburgh

John M. Jakicic1, Jacqueline Wesche-Thobaben2; Kirk Erickson3; Andrea Hergenroeder3; Scott Kurdilla; Regina L. Leckie; Juliet Mancino; Meghan McGuire; Tracey Murray; Anna Peluso; Deborah Viszlay; Jen C. Watt

-

The Miriam Hospital/Alpert Medical School of Brown University

Rena R. Wing1; Caitlin Egan2; Kathryn Demos3; Kirsten Annis; Ryan Busha; Casie Damore; Causey Dunlap; Lynn Fanella; Lucas First; Michelle Fisher; Stephen Godbout; Anne Goldring; Ariana LaBossiere

-

MRI Reading Center

Nick Bryan1; Lisa Desiderio2; Christos Davatzikos; Guray Erus; Meng-Kang Hsieh; Ilya Nasrallah

Coordinating Center

-

Wake Forest School of Medicine

Mark A. Espeland1; Judy Bahnson2; Delilah Cook2; Amelia Hodges2, Ramon Casanova3; Satoru Hayasaka3; Paul Laurienti3; Robert Lyday3; Jerry M. Barnes; Tara D. Beckner; Lea Harvin; Debra Hege; Rebecca H. Neiberg; Ginger Pate

All other staff is listed alphabetically by site.

Footnotes

Principal Investigator

Program Coordinator

Co-Investigator

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00017953

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Authors Contributions: All authors meet the criteria for authorship stated in the Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals.

Sponsors Role: Representatives from the sponsor (NIDDK) reviewed this manuscript prior to submission, serving on the Look AHEAD Publications and Presentations Committee, but had no direct role in its development and final submission.

References

- 1.Nealon RS, Howe PR, Jansen L, et al. Impaired cerebrovascular responsiveness and cognitive performance in adults with type 2 diabetes. J Diab Complic. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2016.06.025. S1056–8272(16)30254–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Willeumier KC, Taylor DV, Amen DG. Elevated BMI is associated with decreased blood flow in the prefrontal cortex using SPECT imaging in healthy adults. Obesity. 2011;19:1095–1097. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tucsek Z, Toth P, Tarantini S, et al. Aging exacerbates obesity-induced cerebrovascular rarefaction, neurovascular uncoupling, and cognitive decline in mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69:1339–1352. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birdsill AC, Carlsson CM, Willette AA, et al. Lower cerebral blood flow is associated with lower memory function in metabolic syndrome. Obesity. 2013;21:1313–1320. doi: 10.1002/oby.20170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fazekas F, Niederkorn K, Schmidt R, et al. White matter signal abnormalities in normal individuals: correlation with carotid ultrasonography, cerebral blood flow measurements, and cerebrovascular risk factors. Stroke. 1988;19:1285–1288. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.10.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamura MK, Pajewski NM, Bryan RN, et al. Chronic kidney disease, cerebral blood flow, and white matter volume in hypertensive adults. Neurology. 2016;86:1208–1216. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes JN. Exercise, cognitive function, and aging. Adv Physiol Educ. 2015;39:55–62. doi: 10.1152/advan.00101.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Look AHEAD Research Group. Design and methods for a clinical trial of weight loss for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Control Clin Trials. 2003;24:610–628. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(03)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Look AHEAD Research Group. Long-term effects of a lifestyle intervention on weight and cardiovascular risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus: four year results of the Look AHEAD trial. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1566–1575. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Espeland MA, Erickson K, Neiberg RH, et al. Brain and white matter hyperintensity volumes after ten years of random assignment to lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:764–771. doi: 10.2337/dc15-2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Espeland MA, Rapp SR, Bray GA, et al. Long-term impact of behavioral weight loss intervention on cognitive function. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69:1101–1108. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Espeland MA, Luchsinger JA, Baker LD, et al. Effect of a long-term intensive lifestyle intervention on prevalence of cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2017;88:2026–2035. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Look AHEAD Research Group. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. New Eng J Med. 2013;369:145–154. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Look AHEAD Research Group. The Look AHEAD Study: a description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting it. Obesity. 2006;14:737–752. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jung Y, Wong EC, Liu TT. Multiphase pseudocontinuous arterial spin labeling (MP-PCASL) for robust quantification of cerebral blood flow. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64:799–810. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ye FQ, Frank JA, Weinberger DR, et al. Noise reduction in 3D perfusion imaging by attenuating the static signal in arterial spin tagging. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44:92–100. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200007)44:1<92::aid-mrm14>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu G, Rowley HA, Wu G, et al. Reliability and precision of pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling perfusion MRII on 3. 0 T and comparison with 150-water PET in elderly subjects at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. NMR Biomed. 2010;23:286–293. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daulatzai MA. Cerebral hypoperfusion and glucose hypometabolism: key pathophysiological modulators promote neurodegeneration, cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci Res. 2017;95:943–972. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin TN, Sun SW, Cheung WM, et al. Dynamic changes in cerebral blood flow and angiogenesis after transient cerebral ischemia in rats. Stroke. 2002;33:2985–2991. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000037675.97888.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perrey S. Promoting motor function by exercising the brain. Brain Sci. 2013;3:101–122. doi: 10.3390/brainsci3010101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brundel M, van den Berg E, Reijmer YD, et al. Cerebral haemodynamics, cognition and brain volumes in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diab Complic. 2012;26:205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2012.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boraxbekk CJ, Salami A, Wahlin A, et al. Physical activity over a decade modifies age-related decline in perfusion, gray matter volume, and functional connectivity of the posterior default-mode network – a multimodal approach. Neuroimage. 2016;131:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maass A, Duzel S, Goerke M, et al. Vascular hippocampal plasticity after aerobic exercise in older adults. Molecul Psych. 2015;20:585–593. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selim M, Jones R, Novak P, et al. The effects of body mass index on cerebral blood flow. Clin Auton Res. 2008;18:331–338. doi: 10.1007/s10286-008-0490-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The Look AHEAD Research Group. Effect of a long-term behavioural weight loss intervention on nephropathy in overweight or obese adults with type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:801–809. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70156-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pownall HJ, Schwartz AV, Bray GA, et al. Changes in regional body composition over 8 years in a randomized lifestyle trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015;24:1899–1905. doi: 10.1002/oby.21577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belalcazar LM, Reboussin DM, Haffner SM, et al. A 1-year lifestyle intervention for weight loss in persons with type 2 diabetes reduces high C-reactive protein levels and identifies metabolic predictors of change. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2297–2303. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loane DJ, Kumar A. Microglia in the TBI brain: the good, the bad, and the dysregulated. Exp Neurol. 2016;275:316–327. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abbenhardt C, McTiernan A, Alfano CM, et al. Effects of individual and combined dietary weight loss and exercise interventions in postmenopausal women on adiponectin and leptin levels. J Intern Med. 2013;274:163–175. doi: 10.1111/joim.12062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castan-Laurell I, Vitkova M, Daviaud D, et al. Effect of hypocaloric diet-induced weight loss in obese women on plasma apelin and adipose tissue expression of apelin and APJ. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;158:905–910. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castan-Laurell I, Dray C, Attane C, et al. Apelin, diabetes, and obesity. Endocrine. 2011;40:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s12020-011-9507-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Busch HJ, Schirmer SH, Jost M, et al. Leptin augments cerebral hemodynamic reserve after three-vessel occlusion: distinct effects on cerebrovascular tone and proliferation in a nonlethal model of hypoperfused rat brain. J Cerebral Blood Flow Metal. 2011;31:1085–1092. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tahergorabi Z, Khazaej M. Leptin and its cardiovascular effects: focus on angiogenesis. Adv Biomed Res. 2015;4:79. doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.156526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sawicka M, Janowska J, Chudek J, et al. Potential beneficial effect of some adipokines positively correlated with the adipose tissue content on the cardiovascular system. Int J Cardiol. 2016:22581–22589. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meng L, Hou W, Chui J, et al. Cardiac output and cerebral blood flow: the integrated regulation of brain perfusion in adult humans. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:1198–1208. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Unick JL, Beavers D, Bond DS, et al. The long-term effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention in severely obese individuals. Am J Med. 2013;126:236–242. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table 1: Body mass index and self-reported physical activity at baseline and changes from baseline.