Abstract

Nanotechnology offers innovation in products from cosmetics to drug delivery, leading to increased engineered nanomaterial (ENM) exposure. Unfortunately, health impacts of ENM are not fully realized. Titanium Dioxide (TiO2) is among the most widely produced ENM due to its use in numerous applications. Extrapulmonary effects following pulmonary exposure have been identified and may involve reactive oxygen species (ROS). The goal of this study was to determine the extent of ROS involvement on cardiac function and the mitochondrion following nano-TiO2 exposure. To address this question, we utilized a transgenic mouse model with overexpression of a novel mitochondrially-targeted antioxidant enzyme (phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase; mPHGPx) which provides protection against oxidative stress to lipid membranes. MPHGPx mice and littermate controls were exposed to nano-TiO2 aerosols (Evonik, P25) to provide a calculated pulmonary deposition of 11μg/mouse. Twenty-four hours following exposure, we observed diastolic dysfunction as evidenced by E/A ratios greater than 2 and increased radial strain during diastole in wild-type mice (P<0.05 for both), indicative of restrictive filling. Overexpression of mPHGPx mitigated the contractile deficits resulting from nano-TiO2 exposure. To investigate the cellular mechanisms associated with the observed cardiac dysfunction, we focused our attention on the mitochondrion. We observed a significant increase in ROS production (P<0.05) and decreased mitochondrial respiratory function (P<0.05) following nano-TiO2 exposure which were attenuated in mPHGPx transgenic mice. In summary, nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure is associated with cardiac diastolic dysfunction and mitochondrial functional alterations, which can be mitigated by the overexpression of mPHGPx, suggesting ROS contribution in the development of contractile and bioenergetics dysfunction.

Keywords: Mitochondria, Cardiac Function, Titanium Dioxide, Reactive Oxygen Species, Antioxidant

INTRODUCTION

A strong link between cardiovascular disease and particulate matter exposure have been previously highlighted, but the impact of nano-sized particles on the heart is not well understood. Cardiovascular endpoints such as decreased vascular reactivity in rats (Nurkiewicz et al., 2009) and diminished cardiac function in zebrafish (Duan et al., 2016) have been suggested following nanomaterial exposure, but murine studies have not fully realized cardiac functional impacts of engineered nanomaterial (ENM) exposure. With the increasing translational prevalence of ENM and the pervasiveness of inhalation studies, understanding the effects of these materials on the heart is crucial to the overall understanding of the health impacts of nanomaterial exposure.

TiO2 is one of the most broadly applied ENM, commonly used as a pigment and photocatalyst additive of paint, food, and sunscreen to enhance the appearance of the product. The ratio of nano-TiO2 to TiO2 continues to increase and predictions estimate the market to be entirely within the nanoscale by 2025 (Robichaud et al., 2009). Exposure to TiO2 has been shown to induce negative cardiac effects centered on the dysregulation of the oxidative milieu (Sha et al., 2013, Sheng et al., 2013). Functionally, acute pulmonary nano-TiO2 exposure induces diastolic dysfunction in rats (Kan et al., 2012), yet the direct role of oxidative stress on the dysfunction is unknown. Long-term gastric exposure to nano-TiO2 has been shown to increase reactive oxygen species (ROS) concomitant with a decreased antioxidant capacity within the heart (Chen et al., 2015). In vitro analyses have implicated mitochondrial ROS production as central to the pathways of toxicity following nano-TiO2 exposure (Huerta-Garcia et al., 2014). However, the role of the mitochondrion in the cardiovascular response to acute nano-TiO2 exposure in vivo is not fully understood.

The mitochondrion has been implicated in the etiology of many cardiovascular diseases due to the crucial roles it plays within the cardiomyocyte. Among the central roles for cardiac mitochondria is the production of ATP requisite for contraction and relaxation as well as its contribution to cellular oxidative milieu. To aid in the protection, ROS within the mitochondria are regulated by mitochondrial antioxidant enzymes including mitochondrial phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase (mPHGPx) also known as GPx4 (Ji et al., 1998, Arai et al., 1999). GPx4 primarily exists in two regionally specific forms: the long form with a mitochondrial targeting sequence that exists in the mitochondrion (mPHGPx) and the short form which does not contain a mitochondrial targeting sequence, and is found outside of the mitochondrion (Imai and Nakagawa, 2003). This mitochondrial antioxidant is particularly interesting because it is a lipophilic enzyme capable of reducing peroxidized acyl groups in phospholipids (Ursini et al., 1985), fatty acids hydroperoxides (Schnurr et al., 1996) and cholesterol peroxides (Thomas et al., 1990) in biological membranes and is the primary antioxidant defense against oxidation of mitochondrial biomembranes.

In the current study, we determined the impact of acute ENM inhalation exposure (nano-TiO2) on cardiac function and mitochondrial metabolism. We hypothesized that nano-TiO2 exposure induces cardiac dysfunction arising from disturbed mitochondrial function. To test the hypothesis, we utilized a transgenic mouse model in which the mitochondrial form of GPx4 (mPHGPx) was overexpressed, in an effort to determine the specific contribution of mitochondrially-derived ROS. Our results indicate that mitochondria-specific overexpression of GPx4 provides protection to both cardiac contractile and mitochondrial function following acute nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental Animals

The animal experiments in this study were approved by the West Virginia University Animal Care and Use Committee and conformed to the most current National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals manual. Male FVB mice were housed in the West Virginia University Health Sciences Center Animal Facility and given access to a rodent diet and water ad libitum. To verify genetic overexpression, DNA from 3-week-old mice was isolated from tail clips and screened using a real-time PCR (RT-PCR) approach as previously described (Dabkowski et al., 2008, Baseler et al., 2013). Briefly, we probed for GPx4 using a custom-designed fluorometric probe (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and RT-PCR on an Applied Biosystems 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). These animals have been previously shown to have increased PHGPx protein concentrations in the mitochondria (Dabkowski et al., 2008). In addition to the increased mitochondrial protein content, mPHGPx overexpressing mice display increased phosphatidylcholine hydroperoxide scavenging ability, which is a specific substrate of GPx4 (Dabkowski et al., 2008).

Engineered Nanomaterial Inhalation Exposure

Nano-TiO2 P25 powder was obtained from Evonik (Aeroxide TiO2, Parsippany, NJ). Previously, this powder was identified to be a mixture composed of anatase (80%) and rutile (20%) TiO2, with a primary particle size of 21 nm and a surface area of 48.08 m2/g. Using a Zetasizer Nano Z (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK) we determined the Z-potential of these particles as −56.6 mV. The nano-TiO2 was prepared with care prior to aerosolization by drying, sieving and storing the powder.

The nanoparticle aerosol generator was developed, designed and tested specifically for rodent nanoparticle inhalation exposures (US patent #8,881,997) as previously described (Yi et al., 2013). The test atmospheres were monitored in real time with an electrical low pressure impactor (ELPI, Dekati, Tampere, Finland) and data from the ELPI indicated that the count median aerodynamic diameter of the particles was 142.1 ± 10.5 nm (Figure 1A; n=4). The test atmospheres were adjusted manually throughout the exposure duration to assure a consistent and known exposure for each animal group (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Nanomaterial Inhalation Characterization.

(A) Electrical Low Pressure Impactor (ELPI) count median aerodynamic diameter Dp = 131.6 nm. (B) Titanium Dioxide aerosol mass concentration throughout the inhalation exposure measured with ELPI. Dashed black line is the average exposure concentration.

Once a steady-state aerosol concentration was achieved, exposure duration was adjusted to achieve a calculated deposition of 11.58 ± 0.27 μg. Calculated total deposition was based on mouse methodology previously described and normalized to minute ventilation using the following equation: D = F x V x C x T, where F is the deposition fraction (10%), V is the minute ventilation based on body weight, C equals the mass concentration (mg/m3) and T equals the exposure duration (minutes) (Porter et al., 2013).

Echocardiography

Echocardiographic assessments were carried out as previously described (Baseler et al., 2013, Jagannathan et al., 2015, Shepherd et al., 2015, Thapa et al., 2015). Briefly, each mouse was anesthetized with inhalant isoflurane then maintained at 1% isoflurane or lower in order to sustain a physiologically relevant heart rate range for the duration of the experiment, effectively minimizing the consequences of anesthesia. Brightness and motion mode imaging was accomplished via a 32-55 MHz linear array transducer using the highest possible frame rate (233-401 frames/second) on a Vevo2100 Imaging System (Visual Sonics, Toronto, Canada). All images were acquired by one individual blinded to animal group.

Conventional echocardiographic assessment was completed on grayscale M-mode parasternal short-axis images at the mid-papillary level of the LV. All M-mode image measurements were calculated over 3 consecutive cardiac cycles and then averaged. To assess diastolic function, LV filling was evaluated using mitral valve Doppler echocardiography and measured over 3 cardiac cycles.

Speckle-tracking based strain assessments were performed by tracing the walls of the endocardium and epicardium on B-mode video loops and analyzed throughout the 3 cardiac cycles using Visual Sonics VevoStrain software (Toronto, Canada) employing a speckle-tracking algorithm. The software then generated time-to-peak analysis for curvilinear data as output for strain and strain rate. The same trained, blinded investigator using the Vevo2100 Imaging analysis software (Visual Sonics, Toronto, Canada) completed all analyses.

Tissue Preparation and Compartment Isolation

After cardiac contractile measurements were performed, mice were euthanized, hearts excised and cardiac mitochondria isolated via differential centrifugation. Subsarcolemmal mitochondria (SSM) and interfibrillar mitochondria (IFM) subpopulations were isolated as previously described following the methods of Palmer et al. (Palmer et al., 1977) with minor modifications by our laboratory (Dabkowski et al., 2010, Baseler et al., 2011, Baseler et al., 2013, Croston et al., 2013, Thapa et al., 2015). Mitochondrial pellets were resuspended in KME buffer (100 mM KCl, 50 mM MOPS and 0.5 mM EGTA pH 7.4) and utilized for all analyses. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford method using bovine serum albumin as a standard (Bradford, 1976).

Mitochondrial Respiration

State 3 and state 4 respiration rates were analyzed in freshly isolated mitochondrial subpopulations as previously described (Chance and Williams, 1955, Chance and Williams, 1956) with modifications by our laboratory (Dabkowski et al., 2008, Dabkowski et al., 2010, Croston et al., 2014, Thapa et al., 2015). Briefly, isolated mitochondrial subpopulations were resuspended in KME buffer and protein content was determined by the Bradford method. Mitochondria protein was added to respiration buffer (80 mM KCl, 50 mM MOPS, 1 mmol/l EGTA, 5 mmol/l KH2PO4, and 1 mg/ml BSA) and placed into a respiration chamber connected to an oxygen probe (OX1LP-1mL Dissolved Oxygen Package, Qubit System, Kingston, ON, Canada). Maximal complex I-mediated respiration was initiated by the addition of glutamate (5 mM) and malate (5 mM). Data for state 3 (250 mM ADP) and state 4 (ADP-limited) respiration were expressed as nmol of oxygen consumed/min/mg protein.

Mitochondrial Hydrogen Peroxide Production

Cardiac mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide production was analyzed following nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure utilizing the fluorescent dye Amplex Red. The Amplex Red reagent reacts with hydrogen peroxide in a 1:1 stoichiometry to produce the red-fluorescent oxidation product, resorufin. Experiments were carried out following manufacturer’s instructions with minor modifications. Briefly, isolated mitochondria were incubated with reaction buffer and Amplex Red dye was added before fueling mitochondria with glutamate, malate and ADP. Changes in fluorescence over time were read on a Molecular Devices Flex Station 3 fluorescent plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and normalized per milligram of protein.

Lipid Peroxidation Products

Lipid peroxidation was assessed in isolated mitochondrial subpopulation and cytosolic fractions through the measurement of stable, oxidized end products of polyunsaturated fatty acids and esters: malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxyalkenal (4-HAE) as previously described (Dabkowski et al., 2008, Baseler et al., 2013). Briefly, one molecule of either MDA or 4-HAE reacts with two molecules of N-methyl-2-phenylindole (Oxford Biomedical Research Company, Oxford, MI) to yield a stable chromophore whose absorbance was measured on a Molecular Devices Flex Station 3 spectrophotometric plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). As a supplementary evaluation of cytosolic lipid peroxidation, MDA was assessed using a classic thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) approach (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). Protein content was assessed by the Bradford method, as above, and values were normalized per milligram of protein.

iTRAQ Labeling and Mass Spectrometry Analyses

Pooled isolated mitochondrial subpopulations from control and exposed mice both wild-type and mPHGPx transgenic were prepared as previously described (Dabkowski et al., 2010, Baseler et al., 2011, Baseler et al., 2013). Pooled samples were labeled with iTRAQ reagents per manufacturer’s protocol (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Fractionated samples were combined creating a protein digest sample which was submitted for LS-MALDI TOF/TOF mass spectral analysis for protein identification, characterization and differential expression analysis as previously described (Dabkowski et al., 2010, Baseler et al., 2011) with slight modifications. Briefly, a Q Exactive MS (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA) was utilized with Xcalibur 3.0 software. The resulting spectra were analyzed using ABI ProteinPilot software 4.0 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Canonical Pathways and Molecular Network Analysis

Proteomic outputs were input into Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software and run through the core analysis (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany, www.qiagen.com/ingenuity). Dysregulated proteins were organized into their most representative biological function. Changes in protein expression are presented as nano-TiO2 exposed compared to control and mPHGPx nano-TiO2 exposed compared to control nano-TiO2 exposed for both SSM and IFM. All changes are depicted as increasing, decreasing, or sustained proteomic expression compared to controls. Red color indicates significantly increased expression while significantly decreased expression is in green compared to control groups.

Staining and Tracking TiO2 nanoparticles

TiO2 nanoparticles were isolated from mitochondrial samples, and stained using Alizarin Red S (Acros Organics, Thermo Scientific). Nanomaterial staining was conducted as previously described (Thurn et al., 2009) with slight modifications. Standards were produced using pure TiO2, and prepared concomitant with all samples. Samples were dissolved in hot sulfuric acid then diluted with molecular grade water. The solution was dialyzed against a filtered 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer solution (dibasic anhydrous Na2HPO4, pH of 7.4) for 48 hours using Float-A-Lyzer G2 dialysis cassettes (Thermo Fisher). A fresh, filtered 0.9 mM Alizarin Red S solution was mixed with the dialyzed nanoparticle solution at a 7:3 sample to stain ratio. Samples were centrifuged and sonicated then analyzed immediately to prevent nanoparticle conjugate formation.

Nanoparticle tracking analyses were performed using a NanoSight NS300 (Malvern, Worcestershire, United Kingdom). All samples were analyzed using the green 532 nm laser and 565 nm filter for fluorescence. Camera level and gain were adjusted for each sample to obtain accurate tracking. Fluorescently labeled particles were tracked using the highest camera level, a gain of 1, and a threshold that allowed particle tracking excluding background measurements.

Statistics

Mean and standard error (SE) were calculated for all data sets. A One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was employed with a Bonferroni post-Hoc test to analyze differences between treatment groups using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Cardiac Function Following Nano-TiO2 Inhalation Exposure

While it has been shown that nano-TiO2 inhalation induces cardiac arteriole dysfunction (LeBlanc et al., 2009, LeBlanc et al., 2010), cardiac functional measures have been limited. In this study we utilized conventional, pulsed wave Doppler flow and speckle-tracking based strain measures of echocardiography to thoroughly and sensitively measure cardiac function in vivo following nano-TiO2 inhalation. Within our study, diametric and spatial parameters identified by M-Mode echocardiography were not significantly changed with mPHGPx overexpression or following nano-TiO2 inhalation when compared to control (Table 1). These data suggest that no overt systolic dysfunction is observed with acute nano-TiO2 exposure.

Table 1.

M-Mode Echocardiographic Measurements. Values are means ± SE; n = 8 for each group.

| Control Average ±SEM | Exposed Average ±SEM | mPHGPx Average ±SEM | mPHGPx Exposed Average ±SEM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Rate | BPM | 505.43 ±6.35 | 502.36 ±24.21 | 480.57 ±16.07 | 506.97 ±14.63 |

| Cardiac Output | mL/min | 12.63 ±1.10 | 12.79 ±1.39 | 14.53 ±1.66 | 15.73 ±0.77 |

| LVIDd | mm | 2.86 ±0.11 | 3.02 ±0.21 | 3.16 ±0.16 | 3.35 ±0.11 |

| LVIDs | mm | 1.54 ±0.09 | 1.64 ±0.15 | 1.83 ±0.11 | 1.97 ±0.08 |

| Ejection Fraction | % | 79.13 ±1.66 | 78.22 ±2.69 | 74.65 ±1.32 | 73.16 ±1.03 |

| Fractional Shortening | % | 46.39 ±1.61 | 46.17 ±2.64 | 42.35 ±1.07 | 41.19 ±0.83 |

| Stroke Volume | uL | 24.89 ±2.06 | 28.93 ±4.58 | 30.49 ±3.60 | 33.77 ±2.55 |

| EDV | uL | 31.68 ±3.07 | 37.47 ±5.98 | 41.11 ±5.06 | 46.29 ±3.65 |

| ESV | uL | 6.78 ±1.11 | 8.54 ±1.76 | 10.63 ±1.55 | 12.52 ±1.21 |

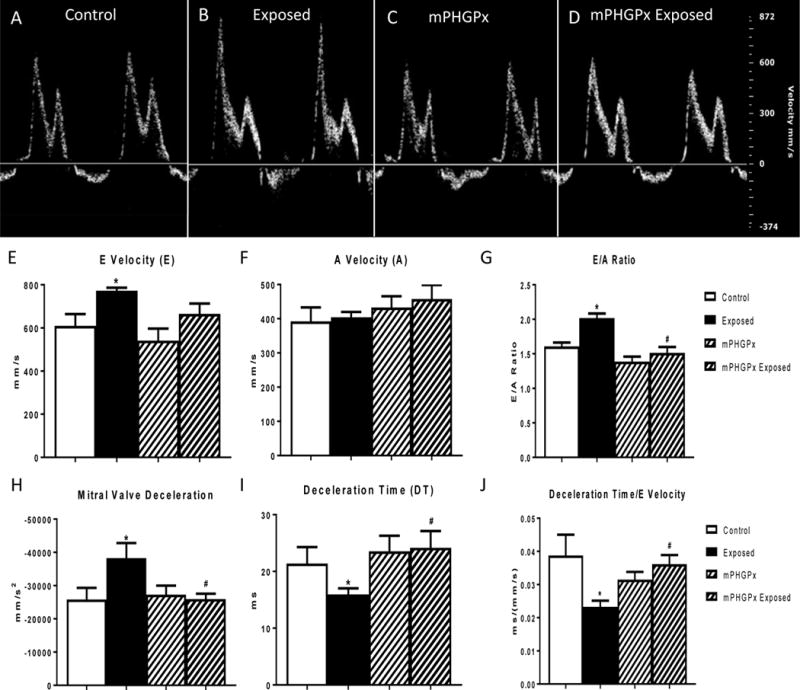

One common diastolic measure utilizes pulsed wave Doppler flow through the mitral valve. In this measure, the individual contribution of the passive left ventricle suction during early diastole (E wave) and the active contraction of the left atria during late diastole (A Wave) in the refilling of the ventricle can be identified to examine diastolic function through the ratio of E to A. Following exposure to nano-TiO2, there was a significant increase in the velocity of the E wave (Figure 2E), yet no change in the A wave velocity was observed (Figure 2F). This change in E without an accompanying change in A led to an increase in the E/A Ratio (Figure 2G) over 2.0 following exposure to nano-TiO2 and is indicative of restrictive filling of the left ventricle during diastole. Deceleration of the mitral valve following exposure was increased (Figure 2H) prompting investigation into the effects of nano-TiO2 on the deceleration time of the mitral valve filling velocity. Deceleration time of early mitral flow, a marker of stiffness routinely measured during the quantitation of diastolic function, was shortened following exposure to nano-TiO2 further supporting that the heart is stiffer following exposure to nano-TiO2 (Figure 2I). To complete our analyses of diastolic function following nano-TiO2 exposure, we normalized deceleration time to the early filling velocity (E). In humans, this measure has been shown to augment the prognostic power of mitral valve tissue Doppler flow indices and predicts heart failure hospitalization (Mishra et al., 2011). Following nano-TiO2 exposure, the normalization of deceleration time to early filling velocity decreased supporting the conclusion that ENM exposure induces diastolic dysfunction (Figure 2J). The diastolic dysfunction observed with nano-TiO2 exposure was attenuated with overexpression of mPHGPx. The increased E wave velocity observed with exposure was attenuated with mPHGPx and not significant from either the wild-type control or exposed groups (Figure 2E). This coupled with no change in the A wave (Figure 2F) led to a decrease in the E/A ratio as compared to the wild-type exposed animals but no change compared to filtered air exposed animals of either genotype (Figure 2G). Further, the rectification of diastolic dysfunction with mPHGPx overexpression was supported by the decrease of mitral valve deceleration (Figure 2H), an increase in mitral valve deceleration time (Figure 2I) and increased ratio of the deceleration time with E wave velocity (Figure 2J) as compared to wild-type nano-TiO2 exposed. These values were not significantly different than the wild-type control exposed animals. Thus, the overexpression of mPHGPx attenuated the diastolic dysfunction observed with acute nano-TiO2 exposure.

Figure 2. Mitral Valve Pulsed-Wave Doppler Flow.

Representative images from pulsed-wave Doppler flow through the mitral valve analyses in control (A), nano-TiO2 exposed (B), mPHGPx (C) and mPHGPx nano-TiO2 exposed (D). Summary data for early mitral valve filling velocity (E wave) (E) and late mitral valve filling velocity (A wave) (F) in control, nano-TiO2 exposed, mPHGPx control and mPHGPx nano-TiO2 exposed. Ratiometric analysis of E wave velocity to A Wave velocity in control, nano-TiO2 exposed, mPHGPx control and mPHGPx nano-TiO2 exposed (G). Deceleration of early mitral valve filling velocity (E wave) in control, nano-TiO2 exposed, mPHGPx control and mPHGPx nano-TiO2 exposed (H). Deceleration time of early mitral valve filling velocity (E wave) in control, nano-TiO2 exposed, mPHGPx control and mPHGPx nano-TiO2 exposed (I). Normalization of deceleration time of early mitral valve filling velocity to the early filling velocity in control, nano-TiO2 exposed, mPHGPx control and mPHGPx nano-TiO2 exposed (J). Values are means ± SE; n = 8 for each group. *P<0.05 vs. Control. #P<0.05 vs Nano-TiO2 Exposed.

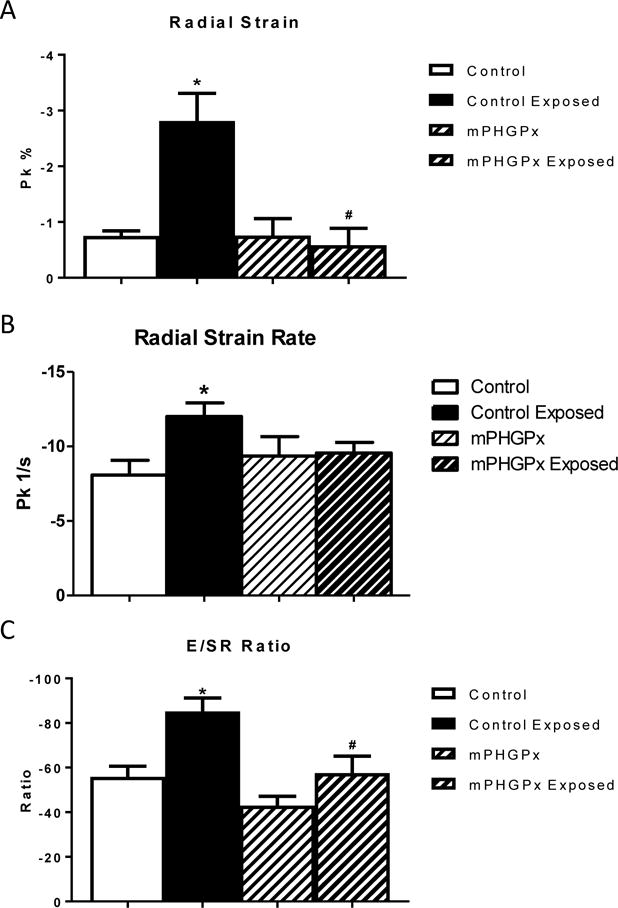

To complement the pulse wave Doppler flow data, we investigated the strain on the heart during diastole utilizing speckle-tracking echocardiography. Following an acute inhalation exposure to nano-TiO2, there was a significant increase in the radial strain and strain rate throughout the wall of the left ventricle (Figure 3A and B). The increased strain and strain rate further suggest restrictive filling of the left ventricle throughout diastole. Following work that identified that the ratio of the E wave velocity (E) to radial strain rate (SR) most closely correlates non-invasive cardiac phenotyping to human cardiac catheterization pressures during diastolic dysfunction (Chen et al., 2014), we investigated the index of E/SR following nano-TiO2 exposure. The ratio of E/SR was significantly increased following nano-TiO2 exposure (Figure 3C), complementing our previous data. Overexpression of mPHGPx attenuated the increased speckle-tracking based strain measures following nano-TiO2 exposure (Figure 3 A-C). These data suggest that following nano-TiO2 exposure, the heart has to work harder during diastole to refill and maintain cardiac systolic function; however, overexpression of mPHGPx, we may be able to attenuate the diastolic dysfunction.

Figure 3. Diastolic Speckle-Tracking Based Strain Analyses.

Diastolic radial strain was analyzed in control, nano-TiO2 exposed, mPHGPx, and mPHGPx nano-TiO2 exposed mice (A). Diastolic radial strain rate analyzed in control, nano-TiO2 exposed, mPHGPx, and mPHGPx nano-TiO2 exposed mice (B). Analysis of the ratio of early mitral valve filling velocity (E) to radial strain rate analyzed in control, nano-TiO2 exposed, mPHGPx, and mPHGPx nano-TiO2 exposed mice (C). Values are means ± SE; n = 8 for each group. *P<0.05 vs. Control. #P<0.05 vs Nano-TiO2 Exposed.

Spatially-Distinct Mitochondrial Function

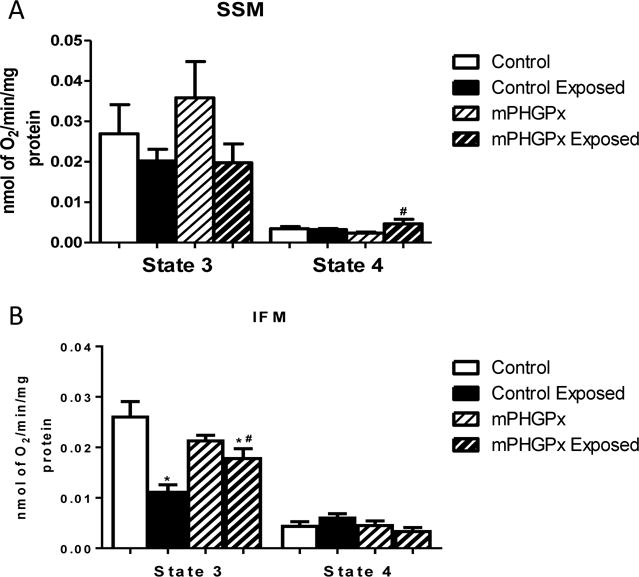

Diastole is an energy intensive process, and mitochondria provide energy necessary for both contraction and relaxation. Mitochondrial respiratory capacity can be assessed by measuring the state 3 and state 4 respiratory rates. Within the cardiomyocyte, there are two spatially and biochemically distinct subpopulations of mitochondria: the SSM which are located below the sarcolemma and the IFM which reside between the myofibrils. Following nano-TiO2 exposure, there was no significant change in either state 3 or state 4 respiratory rate in the SSM (Figure 4A). In contrast, nano-TiO2 exposure decreased state 3 respiratory rates in IFM suggesting decreased mitochondrial function (Figure 4B). MPHGPx overexpression attenuated the decreased state 3 mitochondrial respiratory rate of the IFM following nano-TiO2 exposure (Figure 4B). These data suggest that decreased mitochondrial function accompanies cardiac diastolic dysfunction following nano-TiO2 exposure. Also, these data demonstrate that the decreased mitochondrial function observed following nano-TiO2 exposure is localized to the IFM and treatment with an antioxidant attenuates the damage.

Figure 4. Mitochondrial Respiratory Capacity.

Summary analyses of state 3 and state 4 respiration rates from trace measurements of SSM (A) and IFM (B) in control, nano-TiO2 exposed, mPHGPx and mPHGPx nano-TiO2 exposed. Values are means ± SE; n = 6 for each group. *P<0.05 vs. Control. #P<0.05 vs Nano-TiO2 Exposed. SSM: subsarcolemmal mitochondria, IFM: interfibrillar mitochondria.

Mitochondrial Lipid Peroxidation

ROS damage, including lipid peroxidation, can influence the macromolecular structure impacting organelle function. We investigated the ROS damage by-products malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxyalkenal (4-HAE) to address the impact of mitochondrial ROS. There was a significant increase in lipid damage following nano-TiO2 inhalation in the IFM, which was mitigated with overexpression of mPHGPx (Figure 5B). However, there was no change in lipid peroxidation within any of the groups compared to the control in the SSM (Figure 5A). Further, lipid peroxidation was increased in the cytosol following exposure, yet overexpression of mPHGPx did not attenuate cytosolic lipid peroxidation (Figure 5C and D). Taken together, these findings suggest that ROS damage within the IFM contributes to the observed mitochondrial dysfunction following nano-TiO2 exposure and overexpression of a mitochondrially-targeted antioxidant diminished the damage.

Figure 5. Mitochondrial Lipid peroxidation by-products.

Oxidative damage to lipids was assessed in control, nano-TiO2 exposed, mPHGPx control and mPHGPx nano-TiO2 exposed SSM (A) and IFM (B) subpopulations and cytosol (C) by measuring lipid peroxidation by-products malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxyalkenal (4-HAE). Results were compared against a standard curve of known 4-HAE and MDA concentrations. Cytosolic lipid peroxidation was also assessed using TBARS (D). Values are expressed as means ± SE. n = 8 per each group. *P<0.05 vs. Control. #P<0.05 vs Nano-TiO2 Exposed. $P<0.05 vs. mPHGPx. SSM: subsarcolemmal mitochondria, IFM: interfibrillar mitochondria, Cyto: cytosolic fraction.

Mitochondrial Hydrogen Peroxide Production

SSM isolated from animals exposed to nano-TiO2 showed no increase in hydrogen peroxide production (Figure 6A and C). In contrast, there was a significant increase in hydrogen peroxide production in IFM following exposure to nano-TiO2 (Figure 6B and D). Overexpression of mPHGPx diminished hydrogen peroxide production in the IFM following nano-TiO2 exposure (Figure 6B and D). These data suggest that increased levels of hydrogen peroxide contribute to the oxidative damage in the IFM following nano-TiO2 exposure. The ability of the mPHGPx overexpression to attenuate hydrogen peroxide production emphasizes the critical role of ROS in the mitochondrial dysfunction following nano-TiO2 exposure.

Figure 6. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species Production.

Representative plot of hydrogen peroxide production over time in SSM (A) and IFM (B). Solid lines represent control exposure and dashed lines represent nano-TiO2 exposure. Black lines represent control mice, while grey lines represent mPHGPx mice. Summary data of hydrogen peroxide production expressed as change in fluorescence min−1·mg protein−1 for SSM (C) and IFM (D). Values are expressed as means ± SE. n = 8 per each group. *P<0.05 vs. Control. #P<0.05 vs Nano-TiO2 Exposed. SSM: subsarcolemmal mitochondria, IFM: interfibrillar mitochondria.

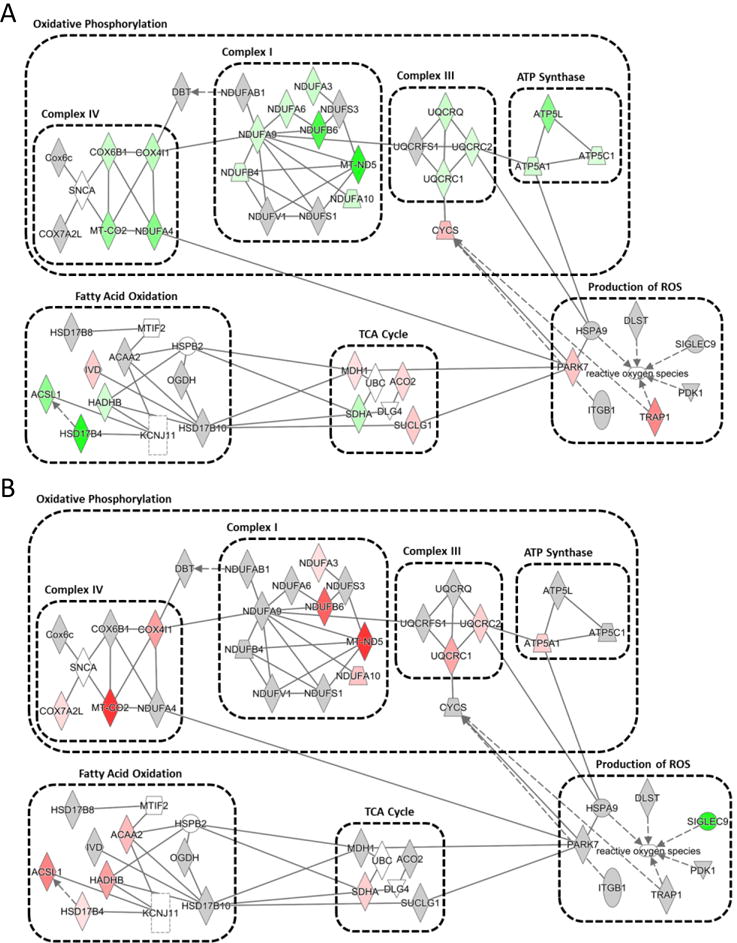

Mitochondrial Proteomic Dysregulation

By utilizing iTRAQ analyses coupled with IPA to gather additional biological insight, we conducted a functional network analysis and identified ROS production, oxidative phosphorylation, and fatty acid oxidation as the top dysregulated proteomic pathways. In the IFM, many proteins throughout the electron transport chain displayed decreased expression following exposure, as compared to control, which supports the suggestion of decreased mitochondrial function (Figure 7A, Supplemental Table). Of the proteins that were increased within the IFM, most were located within the TCA cycle and ROS generation pathways (Figure 7B, Supplemental Table). With overexpression of mPHGPx many of the proteins that were decreased in the IFM following exposure to nano-TiO2 were upregulated compared to exposed control. Changes in the SSM proteome are represented in Supplemental Table. Taken together these data support our previous findings that overexpression of mPHGPx can attenuate mitochondrial proteome disruption and mitochondrial dysfunction following exposure to nano-TiO2.

Figure 7. Mitochondrial Protein Networks.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis of mitochondrial proteomic networks influenced in the IFM by nano-TiO2 exposure (A) and preserved in the IFM of mPHGPx nano-TiO2 exposed (B). Four networks, including reactive oxygen species production, oxidative phosphorylation, citric acid cycle, and fatty acid oxidation were identified. Green indicates proteins increased with nano-TiO2 exposure and red indicates proteins downregulated following nano-TiO2 exposure. Grey indicates proteins unchanged by nano-TiO2 exposure but are part of their respective networks.

Mitochondrial Nanomaterial Tracking

To gain insight into the mechanisms eliciting the observed mitochondrial effects, we determined whether nano-TiO2 was present within the mitochondria following exposure. We isolated nanomaterials from isolated mitochondria and utilized a Malvern NanoSight NS300 to track fluorescently labeled nano-TiO2. We observed a significant increase in fluorescently labeled particles as a ratio to non-labeled particles following inhalation exposure to TiO2 nanomaterials (Figure 8E). This data suggests that following an inhalation exposure nanomaterials may translocate from the lungs and associate with the mitochondria in the heart.

Figure 8. Nanomaterial Tracking within Mitochondria.

Analysis of fluorescently stained nanomaterials isolated from mitochondria isolated from control and nano-TiO2 exposed animals. Representative images using both non-fluorescent and fluorescent settings. Unexposed controls showing particle count and intensity (A). Unexposed controls showing total number of fluorescent particles present over the course of three tracks (B). Nano-TiO2 exposed showing particle count and size (C). Nano-TiO2 exposed showing total number of fluorescent particles. Summary graph (E). Values are expressed as means ± SE. n = 5 per each group. *P<0.05 for Control vs. Nano-TiO2 (Exposed).

DISCUSSION

The proliferation of nanomaterial applications continues to rise, but the impact of these materials on human health is not fully understood. Inhalation of nano-TiO2 has been shown to impact cardiovascular function and ROS production within the heart, yet the influence of the mitochondria on both cardiovascular function and ROS production following acute inhalation exposure is unexplored. Utilizing our nanomaterial inhalation exposure chamber and a novel transgenic mouse line overexpressing the mitochondrial antioxidant enzyme mPHGPx, we examined the role of ROS damage in cardiac mitochondrial disruption and diastolic dysfunction with acute nano-TiO2 exposure. Our data revealed that acute nano-TiO2 inhalation induces diastolic dysfunction associated with increased mitochondrial ROS production and metabolic dysfunction that can be attenuated with overexpression of mPHGPx.

In this study, we observed diastolic dysfunction following inhalation exposure to nano-TiO2. While we are not the first to highlight that diastolic function is altered with exposure to nanomaterials, we are the first to incorporate speckle tracking based strain echocardiography to identify this adverse outcome in an acute setting. Disruption of cardiac diastolic function has been identified following inhalation exposure to nano-TiO2 (Kan et al., 2014, Hathaway et al., 2016). Thus, our data support a growing pool of studies suggesting distinct cardiac dysfunction occurs following exposure. However, our novel analysis utilizes a non-invasive technique for cardiac phenotyping - speckle-tracking based strain echocardiography. Our lab and others have described the benefit of this technique in the early identification of cardiac functional defects that precede overt systolic dysfunction in disease models using both rodents and humans (Liang et al., 2006, Bauer et al., 2011, Shepherd et al., 2015). Because this tool is commonly used to identify early dysfunction, the functional changes identified in our acute model may precede overt dysfunction that would occur in a chronic exposure setting.

Diastolic dysfunction is clinically characterized by a decreased rate of LV relaxation and commonly precedes systolic dysfunction in many cardiac disorders, such as heart failure. By comparing non-invasive speckle-tracking based echocardiographic and invasive cardiac catheterization indices in humans, Chen et al. was able to isolate the combination of non-invasive parameters that best correlate with diastolic function (Chen et al., 2014). While they suggested SR by itself was indicative of LV relaxation, the authors continued that the use of the ratio of E velocity to SR correlated well with left ventricular end-diastolic pressure. Our data indicates that following nano-TiO2 exposure there was an increase in both SR and the ratio of E/SR in the exposed animals. These data further support the use of non-invasive speckle-tracking based strain echocardiography to identify diastolic dysfunction and the validity of our data highlighting dysfunction following nano-TiO2 exposure.

Within the cardiomyocyte, resetting of the cell during diastole to prepare for contraction is an energy intensive process. Mitochondrial dysfunction has been shown to result in diastolic dysfunction in a diabetic model (Flarsheim et al., 1996), but cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction following acute nano-TiO2 exposure has not been investigated. Cardiac mitochondrial function following in vivo nanomaterial exposure has not been intensely investigated, but studies describe decreased mitochondrial function following exposure without elucidating further mechanisms contributing to the dysfunction (Stapleton et al., 2015, Hathaway et al., 2016). In vitro analyses in a variety of cell types suggest that decreased mitochondrial function results from exposure to engineered nanomaterials (Xia et al., 2004, Moschini et al., 2013). Thus, this manuscript highlights that the mitochondria may be central in the extrapulmonary impacts following nanomaterial inhalation exposure.

Systemic effects following a pulmonary exposure have been identified and linked to extrapulmonary impacts. Yet these systemic effects can vary between exposures and may include inflammation (Elder et al., 2004) and particle translocation (Elder and Oberdorster, 2006). In this study, we did not experimentally investigate the systemic stimuli leading to extrapulmonary effects, but it is important to discuss the mechanisms leading to extrapulmonary effects. The most investigated and supported mechanism to lead to these impacts is systemic inflammation (Langrish et al., 2012, Miller et al., 2012). In an acute setting, the quick response of inflammation to xenobiotic particulates suggests inflammation can play a role in the exposures observed. Further, inflammatory responses may directly impact mitochondrial function and biogenesis (Zell et al., 1997, Cherry and Piantadosi, 2015). Other studies have highlighted the role of particle translocation in which inhaled and intratracheally-instilled TiO2 nanoparticles can cross the pulmonary barrier and directly affect the heart in rats (Savi et al., 2014, Husain et al., 2015). Importantly, in this study they also showed that administration of nanoparticles produced cardiac lipid peroxidation (Savi et al., 2014). Further, the presence of these particles in extrapulmonary tissues can regulate gene expression independent of inflammation (Husain et al., 2013).

We have begun to investigate the mechanisms contributing to the observed mitochondrial dysfunction by investigating the presence of nanomaterials within the mitochondrion following exposure. We applied a novel approach by using isolated mitochondria and the Malvern Nanosight NS300, which identifies nanosized particles by fluorescent tagging that can specifically identify nano-TiO2, to investigate if nanomaterials may directly interact with the mitochondrion. In our study, we observed an increase in fluorescently tagged particles within the cardiac mitochondria following pulmonary exposure to nano-TiO2. It is important to note the background within this assay, as the Nanosight will identify all nano-sized particles; thus, the use of the fluorescent tag and presenting the ratio between tagged and untagged nanoparticles is essential in identifying differences due to exposure. By utilizing this approach, we observed an increase in fluorescently-tagged particles suggesting nano-TiO2 within the mitochondria following exposure. This data may support the contention that nano-TiO2 not only translocates from the lung to the heart but may interact with subcellular organelles, and disrupt their function.

Previously, our lab identified cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction following exposure to a regionally specific mountaintop mining particulate matter (Nichols et al., 2015). Further, we identified decreased mitochondrial respiratory rates of both spatially-distinct cardiac mitochondrial subpopulations. These subpopulations are unique both spatially and biochemically. SSM reside below the sarcolemma and are larger and more variable in size relative to IFM. In contrast, IFM reside between the contractile apparatus, are smaller, more compact, and have a higher respiratory rate compared to the SSM. The mountaintop mining particulate previously investigated was non-uniform in size and chemical composition. By comparing these two differing particles, we theorize that particle size may differentially affect mitochondrial subpopulation function. Thus, taken together these studies may suggest that based on size alone, without consideration of chemical composition, the nanomaterial or ultrafine fraction of particulate matter may induce pulmonary and extrapulmonary mechanisms that lead to decreased IFM function, while larger particle sizes induce SSM dysfunction. While this hypothesis has not been thoroughly tested, and would be an interesting subcellular extension of current studies highlighting extrapulmonary impacts of pulmonary exposures, the theory arises from a body of literature suggesting particles of different sizes induce differential effects following exposure (Ferin et al., 1992, Oberdorster et al., 1994, Donaldson et al., 2002). This hypothesis would be supported by differentially impacted intermediate mediators following exposure to the particles of different sizes.

In the mitochondria, mPHGPx exists within the inner membrane space primarily at contact points between the inner and outer mitochondrial membranes. This is important to point out because it suggests that this antioxidant is especially critical in protecting the lipids and proteins within these mitochondrial membranes, such as the electron transport chain complexes. Due to their short half-life and low diffusion dynamics, ROS primarily impact the compartment in which they were produced. In the electron-rich environment near the inner mitochondrial membrane the probability of ROS formation is increased. Thus, overexpression of a mitochondrial antioxidant targeted to the inner mitochondrial membrane is likely to prevent mitochondrial dysfunction at the respiratory complexes, as supported by our current data. Overexpression of mPHGPx was able to attenuate cardiac and mitochondrial dysfunction following nano-TiO2 exposure which is supported by the use of iTRAQ proteomics that identified loss of electron transport chain complexes following exposure to nano-TiO2 and restored with the overexpression of mPHGPx. This manuscript is the first to investigate mitochondrial proteomic dysregulation following nano-TiO2 exposure and helps to identify potential complexes and pathways dysregulated by this type of exposure. These data also further suggest ROS as a central component to the cardiac toxicity of nano-TiO2 inhalation.

With respect to the exposure, this dose is equivalent to a worker in a production facility exposed to the NIOSH recommended exposure limit of 300 μg/m3 for 40 hours a week for 26 days. This dose has been used with other animal models and shown to elicit microvascular dysfunction and systemic oxidative stress (Nurkiewicz et al., 2009). The utilization of our novel inhalation facility creates a translationally relevant exposure model, yet the confirmation of the observed effects in a chronic model would be of future value. Investigation into the effects of acute exposure on cardiac tissue is not without merit due to the tissues critical function. Acute inhalation exposure has been shown to expeditiously induce cardiac dysfunction and disrupt subcellular processes such as oxidative milieu and mitochondrial function (Fu et al., 2014, Sarkar et al., 2014). While most of these effects have been identified in particulate matter exposures, the vast majority of literature suggests that nanomaterials are more toxic than their larger counterparts (Roduner, 2006). Thus, the effects observed in this manuscript add to our limited, current understanding of cardiac mechanisms following nanomaterial exposure. Finally, the exposure concentration used in this study is most relevant to an occupational setting, but due to the rise of nanomaterial incorporation into consumer products and limited pulmonary elimination of nano-TiO2 (Oberdorster et al., 2000), this exposure may become relevant to a larger population.

The data presented in this manuscript show for the first time that acute exposure to nano-TiO2 results in ROS production and damage which drives mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to cardiac dysfunction. Overexpression of a mitochondrially-targeted antioxidant, mPHGPx, which attenuates mitochondrial ROS damage, restores mitochondrial and cardiac function, supporting a central role for ROS as a mechanism of toxicity. Further, our study suggests that there is a spatial component to the mitochondrial dysfunction as shown by differential effects to spatially-distinct mitochondrial subpopulations. We suggest that this may indicate a spatial component to the toxicological trigger. Though this study is specific to nano-TiO2, the nature of this metal oxide particle may enable extrapolation to nanomaterial exposures, in general.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclustion we have demonstrate the impact of acute nano-TiO2 exposure on cardiac diastolic function and the mitochondrial impacts that may contribute to this dysfunction. Utilizing a novel transgenic mouse model, overexpressing the mitochondrial-specific antioxidant enzyme, mPHGPx, we reveal that the cardiac and mitochondrial dysfunction observed following nano-TiO2 exposure is due to an increase in mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide production and the subsequent oxidative damage that occurs. Our data suggest that by enhancing antioxidant capacity of the heart, we can reduce the cardiac and mitochondrial dysfunction resulting from nano-TiO2 exposure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute [R01 HL128485] awarded to JMH. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health from the National Institute of Environmental Safety and Health [R01 ES015022] awarded to TRN. This work was supported by an American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship (AHA 13PRE16850066) awarded to CEN. This work was supported by a National Science Foundation IGERT: Research and Education in Nanotoxicology at West Virginia University Fellowship [1144676] awarded to QAH. This work was supported by an American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship (AHA 17PRE33660333) awarded to QAH. Ingenuity Pathway Analyses were supported by a WV-INBRE Grant [P20GM10343412]. Small animal imaging and image analysis were performed in the West Virginia University Animal Models & Imaging Facility (AMIF), which has been supported by the WVU Cancer Institute and NIH grants P20 RR016440, P30 GM103488 and S10 RR026378. Proteomic experiments were performed in conjunction with Protea Biosciences. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIEHS (Grants 1ZIAES025045-17 and 1ZIAES049019-21).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

References

- Arai M, Imai H, Koumura T, Yoshida M, Emoto K, Umeda M, Chiba N, Nakagawa Y. Mitochondrial phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase plays a major role in preventing oxidative injury to cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4924–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baseler WA, Dabkowski ER, Jagannathan R, Thapa D, Nichols CE, Shepherd DL, Croston TL, Powell M, Razunguzwa TT, Lewis SE, Schnell DM, Hollander JM. Reversal of mitochondrial proteomic loss in Type 1 diabetic heart with overexpression of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;304:R553–65. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00249.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baseler WA, Dabkowski ER, Williamson CL, Croston TL, Thapa D, Powell MJ, Razunguzwa TT, Hollander JM. Proteomic alterations of distinct mitochondrial subpopulations in the type 1 diabetic heart: contribution of protein import dysfunction. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;300:R186–200. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00423.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer M, Cheng S, Jain M, Ngoy S, Theodoropoulos C, Trujillo A, Lin FC, Liao R. Echocardiographic speckle-tracking based strain imaging for rapid cardiovascular phenotyping in mice. Circ Res. 2011;108:908–16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.239574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–54. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance B, Williams GR. Respiratory enzymes in oxidative phosphorylation. I. Kinetics of oxygen utilization. J Biol Chem. 1955;217:383–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance B, Williams GR. Respiratory enzymes in oxidative phosphorylation. VI. The effects of adenosine diphosphate on azide-treated mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1956;221:477–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Yuan J, Qiao S, Duan F, Zhang J, Wang H. Evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by global strain rate imaging in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a simultaneous speckle tracking echocardiography and cardiac catheterization study. Echocardiography. 2014;31:615–22. doi: 10.1111/echo.12424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Wang Y, Zhuo L, Chen S, Zhao L, Luan X, Wang H, Jia G. Effect of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on the cardiovascular system after oral administration. Toxicol Lett. 2015;239:123–30. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry AD, Piantadosi CA. Regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis and its intersection with inflammatory responses. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2015;22:965–76. doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.6200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croston TL, Shepherd DL, Thapa D, Nichols CE, Lewis SE, Dabkowski ER, Jagannathan R, Baseler WA, Hollander JM. Evaluation of the cardiolipin biosynthetic pathway and its interactions in the diabetic heart. Life Sci. 2013;93:313–22. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croston TL, Thapa D, Holden AA, Tveter KJ, Lewis SE, Shepherd DL, Nichols CE, Long DM, Olfert IM, Jagannathan R, Hollander JM. Functional deficiencies of subsarcolemmal mitochondria in the type 2 diabetic human heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;307:H54–65. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00845.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabkowski ER, Baseler WA, Williamson CL, Powell M, Razunguzwa TT, Frisbee JC, Hollander JM. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the type 2 diabetic heart is associated with alterations in spatially distinct mitochondrial proteomes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H529–40. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00267.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabkowski ER, Williamson CL, Hollander JM. Mitochondria-specific transgenic overexpression of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase (GPx4) attenuates ischemia/reperfusion-associated cardiac dysfunction. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:855–65. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson K, Brown D, Clouter A, Duffin R, Macnee W, Renwick L, Tran L, Stone V. The pulmonary toxicology of ultrafine particles. J Aerosol Med. 2002;15:213–20. doi: 10.1089/089426802320282338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan J, Yu Y, Li Y, Li Y, Liu H, Jing L, Yang M, Wang J, Li C, Sun Z. Low-dose exposure of silica nanoparticles induces cardiac dysfunction via neutrophil-mediated inflammation and cardiac contraction in zebrafish embryos. Nanotoxicology. 2016;10:575–85. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2015.1102981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder A, Oberdorster G. Translocation and effects of ultrafine particles outside of the lung. Clin Occup Environ Med. 2006;5:785–96. doi: 10.1016/j.coem.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder AC, Gelein R, Azadniv M, Frampton M, Finkelstein J, Oberdorster G. Systemic effects of inhaled ultrafine particles in two compromised, aged rat strains. Inhal Toxicol. 2004;16:461–71. doi: 10.1080/08958370490439669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferin J, Oberdorster G, Penney DP. Pulmonary retention of ultrafine and fine particles in rats. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1992;6:535–42. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/6.5.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flarsheim CE, Grupp IL, Matlib MA. Mitochondrial dysfunction accompanies diastolic dysfunction in diabetic rat heart. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H192–202. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.1.H192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu PP, Xia Q, Hwang HM, Ray PC, Yu H. Mechanisms of nanotoxicity: generation of reactive oxygen species. J Food Drug Anal. 2014;22:64–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway QA, Nichols CE, Shepherd DL, Stapleton PA, Mclaughlin SL, Stricker JC, Rellick SL, Pinti MV, Abukabda AB, Mcbride CR, Yi J, Stine SM, Nurkiewicz TR, Hollander JM. Maternal Engineered Nanomaterial Exposure Disrupts Progeny Cardiac Function and Bioenergetics. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, ajpheart. 2016 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00634.2016. 00634 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta-Garcia E, Perez-Arizti JA, Marquez-Ramirez SG, Delgado-Buenrostro NL, Chirino YI, Iglesias GG, Lopez-Marure R. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles induce strong oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage in glial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;73:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain M, Saber AT, Guo C, Jacobsen NR, Jensen KA, Yauk CL, Williams A, Vogel U, Wallin H, Halappanavar S. Pulmonary instillation of low doses of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mice leads to particle retention and gene expression changes in the absence of inflammation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013;269:250–62. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain M, Wu D, Saber AT, Decan N, Jacobsen NR, Williams A, Yauk CL, Wallin H, Vogel U, Halappanavar S. Intratracheally instilled titanium dioxide nanoparticles translocate to heart and liver and activate complement cascade in the heart of C57BL/6 mice. Nanotoxicology. 2015;9:1013–22. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2014.996192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai H, Nakagawa Y. Biological significance of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase (PHGPx, GPx4) in mammalian cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34:145–69. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01197-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagannathan R, Thapa D, Nichols CE, Shepherd DL, Stricker JC, Croston TL, Baseler WA, Lewis SE, Martinez I, Hollander JM. Translational Regulation of the Mitochondrial Genome Following Redistribution of Mitochondrial MicroRNA in the Diabetic Heart. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2015;8:785–802. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.115.001067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji LL, Leeuwenburgh C, Leichtweis S, Gore M, Fiebig R, Hollander J, Bejma J. Oxidative stress and aging. Role of exercise and its influences on antioxidant systems. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;854:102–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan H, Wu Z, Lin YC, Chen TH, Cumpston JL, Kashon ML, Leonard S, Munson AE, Castranova V. The role of nodose ganglia in the regulation of cardiovascular function following pulmonary exposure to ultrafine titanium dioxide. Nanotoxicology. 2014;8:447–54. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2013.796536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan H, Wu Z, Young SH, Chen TH, Cumpston JL, Chen F, Kashon ML, Castranova V. Pulmonary exposure of rats to ultrafine titanium dioxide enhances cardiac protein phosphorylation and substance P synthesis in nodose ganglia. Nanotoxicology. 2012;6:736–45. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2011.611915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langrish JP, Bosson J, Unosson J, Muala A, Newby DE, Mills NL, Blomberg A, Sandstrom T. Cardiovascular effects of particulate air pollution exposure: time course and underlying mechanisms. J Intern Med. 2012;272:224–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc AJ, Cumpston JL, Chen BT, Frazer D, Castranova V, Nurkiewicz TR. Nanoparticle inhalation impairs endothelium-dependent vasodilation in subepicardial arterioles. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2009;72:1576–84. doi: 10.1080/15287390903232467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc AJ, Moseley AM, Chen BT, Frazer D, Castranova V, Nurkiewicz TR. Nanoparticle inhalation impairs coronary microvascular reactivity via a local reactive oxygen species-dependent mechanism. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2010;10:27–36. doi: 10.1007/s12012-009-9060-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang HY, Cauduro S, Pellikka P, Wang J, Urheim S, Yang EH, Rihal C, Belohlavek M, Khandheria B, Miller FA, Abraham TP. Usefulness of two-dimensional speckle strain for evaluation of left ventricular diastolic deformation in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:1581–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MR, Shaw CA, Langrish JP. From particles to patients: oxidative stress and the cardiovascular effects of air pollution. Future Cardiol. 2012;8:577–602. doi: 10.2217/fca.12.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra RK, Devereux RB, Cohen BE, Whooley MA, Schiller NB. Prediction of heart failure and adverse cardiovascular events in outpatients with coronary artery disease using mitral E/A ratio in conjunction with e-wave deceleration time: the heart and soul study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2011;24:1134–40. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moschini E, Gualtieri M, Colombo M, Fascio U, Camatini M, Mantecca P. The modality of cell-particle interactions drives the toxicity of nanosized CuO and TiO(2) in human alveolar epithelial cells. Toxicol Lett. 2013;222:102–16. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols CE, Shepherd DL, Knuckles TL, Thapa D, Stricker JC, Stapleton PA, Minarchick VC, Erdely A, Zeidler-Erdely PC, Alway SE, Nurkiewicz TR, Hollander JM. Cardiac and mitochondrial dysfunction following acute pulmonary exposure to mountaintop removal mining particulate matter. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309:H2017–30. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00353.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurkiewicz TR, Porter DW, Hubbs AF, Stone S, Chen BT, Frazer DG, Boegehold MA, Castranova V. Pulmonary nanoparticle exposure disrupts systemic microvascular nitric oxide signaling. Toxicol Sci. 2009;110:191–203. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberdorster G, Ferin J, Lehnert BE. Correlation between particle size, in vivo particle persistence, and lung injury. Environ Health Perspect. 1994;102(Suppl 5):173–9. doi: 10.1289/ehp.102-1567252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberdorster G, Finkelstein JN, Johnston C, Gelein R, Cox C, Baggs R, Elder AC. Acute pulmonary effects of ultrafine particles in rats and mice. Res Rep Health Eff Inst. 2000:5–74. disc 75-86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer JW, Tandler B, Hoppel CL. Biochemical properties of subsarcolemmal and interfibrillar mitochondria isolated from rat cardiac muscle. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:8731–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter DW, Hubbs AF, Chen BT, Mckinney W, Mercer RR, Wolfarth MG, Battelli L, Wu N, Sriram K, Leonard S, Andrew M, Willard P, Tsuruoka S, Endo M, Tsukada T, Munekane F, Frazer DG, Castranova V. Acute pulmonary dose-responses to inhaled multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Nanotoxicology. 2013;7:1179–94. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2012.719649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robichaud CO, Uyar AE, Darby MR, Zucker LG, Wiesner MR. Estimates of upper bounds and trends in nano-TiO2 production as a basis for exposure assessment. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43:4227–33. doi: 10.1021/es8032549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roduner E. Size matters: why nanomaterials are different. Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35:583–92. doi: 10.1039/b502142c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar A, Ghosh M, Sil PC. Nanotoxicity: oxidative stress mediated toxicity of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2014;14:730–43. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2014.8752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savi M, Rossi S, Bocchi L, Gennaccaro L, Cacciani F, Perotti A, Amidani D, Alinovi R, Goldoni M, Aliatis I, Lottici PP, Bersani D, Campanini M, Pinelli S, Petyx M, Frati C, Gervasi A, Urbanek K, Quaini F, Buschini A, Stilli D, Rivetti C, Macchi E, Mutti A, Miragoli M, Zaniboni M. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles promote arrhythmias via a direct interaction with rat cardiac tissue. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2014;11:63. doi: 10.1186/s12989-014-0063-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr K, Belkner J, Ursini F, Schewe T, Kuhn H. The selenoenzyme phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase controls the activity of the 15-lipoxygenase with complex substrates and preserves the specificity of the oxygenation products. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4653–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.4653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha B, Gao W, Wang S, Li W, Liang X, Xu F, Lu TJ. Nano-titanium dioxide induced cardiac injury in rat under oxidative stress. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;58:280–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng L, Wang X, Sang X, Ze Y, Zhao X, Liu D, Gui S, Sun Q, Cheng J, Cheng Z, Hu R, Wang L, Hong F. Cardiac oxidative damage in mice following exposure to nanoparticulate titanium dioxide. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2013;101:3238–46. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd DL, Nichols CE, Croston TL, Mclaughlin SL, Petrone AB, Lewis SE, Thapa D, Long DM, Dick GM, Hollander JM. Early detection of cardiac dysfunction in the type 1 diabetic heart using speckle-tracking based strain imaging. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;90:74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton PA, Nichols CE, Yi J, Mcbride CR, Minarchick VC, Shepherd DL, Hollander JM, Nurkiewicz TR. Microvascular and mitochondrial dysfunction in the female F1 generation after gestational TiO2 nanoparticle exposure. Nanotoxicology. 2015;9:941–51. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2014.984251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thapa D, Nichols CE, Lewis SE, Shepherd DL, Jagannathan R, Croston TL, Tveter KJ, Holden AA, Baseler WA, Hollander JM. Transgenic overexpression of mitofilin attenuates diabetes mellitus-associated cardiac and mitochondria dysfunction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;79:212–23. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JP, Maiorino M, Ursini F, Girotti AW. Protective action of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase against membrane-damaging lipid peroxidation. In situ reduction of phospholipid and cholesterol hydroperoxides. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:454–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurn KT, Paunesku T, Wu A, Brown EM, Lai B, Vogt S, Maser J, Aslam M, Dravid V, Bergan R, Woloschak GE. Labeling TiO2 nanoparticles with dyes for optical fluorescence microscopy and determination of TiO2-DNA nanoconjugate stability. Small. 2009;5:1318–25. doi: 10.1002/smll.200801458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursini F, Maiorino M, Gregolin C. The selenoenzyme phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;839:62–70. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(85)90182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia T, Korge P, Weiss JN, Li N, Venkatesen MI, Sioutas C, Nel A. Quinones and aromatic chemical compounds in particulate matter induce mitochondrial dysfunction: implications for ultrafine particle toxicity. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:1347–58. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi J, Chen BT, Schwegler-Berry D, Frazer D, Castranova V, Mcbride C, Knuckles TL, Stapleton PA, Minarchick VC, Nurkiewicz TR. Whole-body nanoparticle aerosol inhalation exposures. J Vis Exp. 2013:e50263. doi: 10.3791/50263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zell R, Geck P, Werdan K, Boekstegers P. TNF-alpha and IL-1 alpha inhibit both pyruvate dehydrogenase activity and mitochondrial function in cardiomyocytes: evidence for primary impairment of mitochondrial function. Mol Cell Biochem. 1997;177:61–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1006896832582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.