Abstract

Purpose

To report the frequency of binocular vision (BV) anomalies in children with specific learning disorders (SLD) and to assess the efficacy of vision therapy (VT) in children with a non-strabismic binocular vision anomaly (NSBVA).

Methods

The study was carried out at a centre for learning disability (LD). Comprehensive eye examination and binocular vision assessment was carried out for 94 children (mean (SD) age: 15 (2.2) years) diagnosed with specific learning disorder. BV assessment was done for children with best corrected visual acuity of ≥6/9 – N6, cooperative for examination and free from any ocular pathology. For children with a diagnosis of NSBVA (n = 46), 24 children were randomized to VT and no intervention was provided to the other 22 children who served as experimental controls. At the end of 10 sessions of vision therapy, BV assessment was performed for both the intervention and non-intervention groups.

Results

Binocular vision anomalies were found in 59 children (62.8%) among which 22% (n = 13) had strabismic binocular vision anomalies (SBVA) and 78% (n = 46) had a NSBVA. Accommodative infacility (AIF) was the commonest of the NSBVA and found in 67%, followed by convergence insufficiency (CI) in 25%. Post-vision therapy, the intervention group showed significant improvement in all the BV parameters (Wilcoxon signed rank test, p < 0.05) except negative fusional vergence.

Conclusion

Children with specific learning disorders have a high frequency of binocular vision disorders and vision therapy plays a significant role in improving the BV parameters. Children with SLD should be screened for BV anomalies as it could potentially be an added hindrance to the reading difficulty in this special population.

Keywords: Binocular vision anomalies, Learning disability, Non-strabismic binocular vision anomalies, Convergence insufficiency, Accommodative infacility

Resumen

Objetivo

Reportar la frecuencia de las anomalías en la visión binocular (VB) en niños con trastornos específicos de aprendizaje (SLD), y evaluar la eficacia de la terapia visual (TV) en niños con alteraciones en la visión binocular no estrábicas (NSBVA).

Métodos

El estudio se llevó a cabo en un centro para discapacidades de aprendizaje (LD). Se realizó un amplio examen ocular y una valoración de la visión binocular en 94 niños (Media (DE) edad: 15 (2,2) años) con diagnóstico de trastorno específico de aprendizaje. Se llevó a cabo una valoración de la VB en los niños, con agudeza visual mejor corregida de ≥6/9 – N6, que cooperaron durante el examen, y que carecían de patología ocular. En los niños con diagnóstico de NSBVA (n = 46), se aleatorizaron 24 de ellos para terapia visual, sin realizar intervención alguna en los 22 niños restantes, que sirvieron de controles. Al finalizar las 10 sesiones de terapia visual, se realizó una valoración de VB tanto en el grupo de intervención como en el de no intervención.

Resultados

Se encontraron anomalías en la visión binocular en 59 niños (62,8%), de entre los cuales el 22% (n = 13) tenían alteraciones en la visión binocular estrábica (SBVA), y el 78% (n = 46) reflejaron NSBVA. La inflexibilidad acomodativa (AIF) fue la NSBVA más común, estando presente en el 67% de los casos, seguida de la insuficiencia de convergencia (CI) en 25% de ellos. Tras la terapia visual, el grupo de intervención reflejó una mejora significativa en todos los parámetros de VB (prueba de los rangos con signo de Wilcoxon: p < 0,05) exceptuando la vergencia fusional negativa.

Conclusión

Los niños con trastorno específico de aprendizaje tienen una elevada frecuencia de anomalías en la visión binocular, y en ellos la terapia visual juega un papel significativo para la mejora de los parámetros de VB. Deberá supervisarse a los niños con SLD, en relación a las anomalías de VB, que podrían suponer un obstáculo añadido a la dificultad lectora en esta población especial.

Palabras clave: Anomalías en la visión binocular, Trastorno de aprendizaje, Alteraciones en la visión binocular no estrábica, Insuficiencia de convergencia, Inflexibilidad acomodativa

Introduction

Learning disability (LD) has been defined as “A generic term that refers to a heterogeneous group of disorders manifested by significant difficulties in the acquisition and use of listening, speaking, reading, writing, reasoning, or mathematical skills”.1 Specific LDs have been reported to be affecting specific domains of reading, written expression and mathematics, with reading as the majorly affected domain.2 In India, the reported prevalence of specific learning disabilities is 15.17% among 8–11 year old children.3 As reading is a primary concern under the SLD, it also raises concern about the efficiency of the visual system that could contribute to the reading impairment.4 About 80% of children with learning disability are shown to be affected with accommodation and vergence anomalies that include convergence insufficiency (CI), reduced amplitude of accommodation (AOA), reduced accommodative and vergence facility, low accommodative convergence/accommodation (AC/A) ratio and reduced fusional ranges.5, 6

Also children with reading and writing difficulties are shown to have deficits in accommodation and vergence parameters compared to age matched controls without reading and writing difficulties.7, 8, 9, 10, 11 It has been shown that these dysfunctions can interfere with the reading speed, accuracy, and reading efficiency.11 Thus assessing the efficiency of the binocular vision in children with learning disorders is highly recommended. The efficacy of vision therapy in the treatment of binocular vision anomalies is well established among children attending regular stream education.12 Yet there is paucity of randomized controlled trials testing the efficacy of vision therapy in this special population. Among children with reading difficulties and convergence insufficiency, 8 prism dioptres base in prism glasses have been shown to improve reading speed and accuracy. Similarly, computer based home vision therapy has also shown to be effective in improving the vergence and accommodation parameters.7 Certain treatment options such as the use of coloured filters13 and behavioural vision therapy remains controversial.14

This current work aimed to find the frequency of BV problems among children with SLD and to assess the efficacy of VT in improving BV parameters in children with SLD and associated non-strabismic BV anomalies.

Methods

Study approval and setup

The ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Institutional review board and ethics committee of Vision Research Foundation, Chennai and the study adhered to the Tenets of the declaration of Helsinki.

The study was carried out at a school for children with learning disability. All the parents or guardian of each student was given a detailed oral description about the study in a meeting organized for the study purpose and a written consent from the parents were obtained to ensure the child's participation in the study.

Medical history of children

Medical history details of the children were obtained from the school medical records, which included: (a) General medical and birth history, (b) developmental milestones and (c) hearing and speech assessment.

There were 96 children in the school (73 male and 23 female), aged 10–21 years. All the children underwent a comprehensive eye examination and binocular vision testing.

Out of the 96 children, 1 child had Down's syndrome, 1 had pervasive disorder and 94 children had a documented diagnosis of specific learning disability and were enrolled for the study. Eleven of these children had a comorbid diagnosis attention deficit disorder (4 without hyperactivity and 7 with hyperactivity). 89 children had normal general health (92.7%), 14 children were born premature (14.6%), 17 (17.7%) children had delayed milestones, 8 (8.3%) children had delayed speech and none of the children had hearing difficulties. All children had normal IQ levels for age without other associated neurological issues. Among the specific learning disorders, all children had issues with reading, writing and spelling as the primary concern, and no specific diagnosis was available from the school records.

Study design and protocol

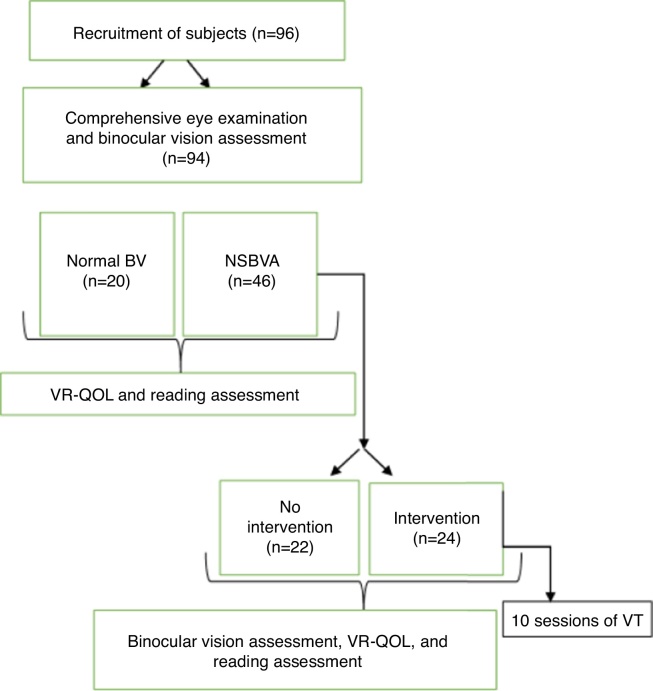

This is a pre–post-experimental study with a no-intervention control group. The study protocol and flow of recruitment is presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Study protocol and flow of recruitment of subjects.

The comprehensive eye examination included:

-

1.

Assessment of presenting visual acuity for distance (using 3 m English log MAR chart) and near (using reduced Snellen at 40 cm).

-

2.

Refractive error with retinoscopy followed by subjective acceptance. Anterior segment examination using torch light and posterior segment using direct ophthalmoscope with high magnification.

Appropriate referrals were made for the children who needed further ophthalmic evaluation. A copy of referral letter was sent to the parents and school administration if the child needed to be referred for ophthalmic evaluation.

The binocular vision testing was carried out with the best corrected refraction in place. If the subject was found to have refractive error for the first time or if a change in refractive error of more than 0.50 D was detected during the refraction, glasses were prescribed and the subject was enrolled after 2 weeks of refractive adaptation.

Binocular vision testing included:

-

1.

Sensory evaluation for near: Using Randot stereo plate.

-

2.Motor evaluation: Motor evaluation comprised of (a) phoria and ocular motility testing, (b) accommodation testing, (c) vergence testing and (d) oculomotor testing.

-

(a)Phoria and ocular motility testing: Assessment of phoria or tropia was done using cover/uncover test and angle of deviation was neutralized using prism base cover test. Extraocular eye movements were assessed using broad H test and versions were assessed in nine cardinal gaze positions.

-

(b)Accommodative testing: The amplitude of accommodation was measured monocularly and binocularly using the push-up test. Monocular values less than 2 dioptres from Hofstetter's minimum expected criteria (15–0.25 (age)) were considered to be abnormal.15Accommodative facility (AF) was assessed in cycles per minute (cpm) both monocularly and binocularly using +2.00/−2.00 D accommodative flipper lenses at 40 cm. Simple three letter words of N8 font size were used as test targets. Monocular AF of 7 cpm for 10–13 years and 11 cpm for greater than 13 years were considered normal.16Monocular estimate method (MEM) retinoscopy was used to assess the accommodative response and a normal lag was considered to be between +0.25 to +0.75 D.16Vergence testing: Near point of convergence (NPC) was assessed using an accommodative target and diplopic response as the target is brought closer was taken as the subjective response. Objective measurement of eye deviation was also noticed and the test was repeated twice to assess the consistency of responses. NPC break ≥6 cm was considered to be abnormal.16Fusional vergence amplitude was measured with prism bar (step vergence) for both distance and near. The negative fusional vergence (NFV) was assessed first followed by positive fusional vergence (PFV). Normative values for diagnosis and diagnostic criteria for NSBVA were adopted and modified from Scheiman and Wick (2014) (Table 1).16

-

(c)Oculomotor testing: The developmental eye movement (DEM) test17 was used to evaluate visual–verbal oculomotor dysfunction. The DEM test consists of three subtests: a pre-test, vertical subtest and horizontal test. The vertical subtest depends on the individual's visual verbal automatic skills. The horizontal subtest consists of numbers arranged in non-symmetrical horizontal array that assessed the horizontal saccadic function.

-

(a)

Table 1.

Diagnostic criteria used for NSBVA diagnosis.

| 1. Convergence insufficiency |

| 1. Exophoria > 4 BI greater for near than distance |

| 2. NPC > 6 cm break with accommodative target |

| 3. PFV < 15 BO (break or blur value) |

| 2. Divergence insufficiency |

| 1. Esophoria > 2 BO for distance |

| 2. NFV < 7 BI (break – step vergence for distance) |

| 3. Convergence excess |

| 1. Significant esophoria at near, >2 prisms |

| 2. Reduced negative fusional vergence < 13/10 for break and recovery |

| 3. High MEM, >+0.75 DS |

| 4. Divergence excess |

| 1. Intermittent to constant exodeviation for distance 5 PD greater than near |

| 2. Low PFV break value of <11 BO for distance |

| 5. Accommodative insufficiency |

| 1. Reduced monocular amplitude of accommodation at least 2 D below Hofstetter's calculation for minimum amplitude: 15–0.25 (age) |

| 2. Difficulty with monocular accommodative facility with −2.00 DS |

| 3. High MEM finding, >+0.75 DS |

| 6. Accommodative infacility |

| 1. Difficulty with both plus and minus lenses in monocular accommodative facility testing with <7 cpm for 8–12 year old and <13 cpm for 13 years and above with ±2.00 DS |

| 2. Difficulty with both plus and minus lenses in binocular accommodative facility testing with <5 cpm using ±2.00 DS |

| 8. Fusional vergence dysfunction |

| 1. Near NFV break <12 BI |

| 2. Near PFV break <23 BO |

| 3. Distance NFV break <7 BI |

| 4. Distance PFV break <11 BO |

| For diagnosis: a minimum of 2 signs are mandatory |

Adopted and modified from Scheiman and Wick (2014).16

The corrected time taken to complete the horizontal and vertical subtests was matched with the provided age norms values and DEM typologies were classified between Type 1 and Type 4. Type 1 specifies normal oculomotor function, Type 2 specifies horizontal scanning or tracking problem, Type 3 indicates automaticity problems, and Type 4 indicates a combination of Type 2 and Type 3 typologies.

Vision related-quality of life assessment

The VR-QOL was assessed using the modified COVD – VR QOL questionnaire consisting of 14 items with 3 response options (0 – Never; 1 – Occasional and 2 – Always). This has been validated as a suitable screening tool among children with learning disability.18 The questionnaire was given to the respective class teachers and scores were obtained for each child. Symptomatology was assessed by asking each child if they have eyestrain, headache, eye pain or any other visual discomfort associated with near visual activities.

Reading assessment

Assessment of reading rate was performed for children diagnosed with non-strabismic binocular vision anomalies (NSBVA). Child was asked to read a given paragraph for 3 min. Subtracting the number of errors made, the reading rate was calculated for 1 min.19 The paragraph was chosen from the child's own grade books that were not familiar to the children. The formula for reading rate is given below:

Randomization

After the diagnosis of NSBVA was made, one half of the children chosen according to the random number tables were allocated to the treatment group and the other half served as control (non-intervention group). Teachers were masked for the name of the children who were allocated for intervention. For ethical reasons, the non-intervention group was also provided with vision therapy after the study was complete.

Intervention

Vision therapy (VT) set-up was planned at the school premises itself. The children who were randomized for intervention were given VT during their class hours for 45 min on alternative day. The VT protocol for the NSBVA was referred from Scheiman and Wick (2014).16 The performance of each child and improvement on each day was noted in a separate proforma. The VT was supplemented under the supervision of a trained optometrist and VT technique was modified wherever necessary according to the responses and difficulty faced by individual child.

Objectives of vision therapy

Computer orthoptics, tranaglyphs and vectograms were the equipment utilized for accommodation and vergence training. For convergence insufficiency, the objectives of the training included improving the convergence fusional ranges, monocular and binocular accommodative facility and to integrate oculomotor training towards the end. For accommodative infacility, the goals of the training included improving the monocular accommodative facility integrated with fusional vergence training.16

Post-vision therapy assessment

At the end of 10 sessions, BV parameters, and reading rate was reassessed in the intervention group. The same assessment was performed in the non-intervention group to assess the true effect of vision therapy negating the placebo, learning and test–retest effects.

Outcome measures

The outcome measures of the study included: (1) frequency of strabismic and non-strabismic binocular vision anomalies (NSBVA) in children with SLD, (2) comparison of visual efficiency and oculomotor parameters between children with normal binocular vision and non-strabismic binocular vision anomalies, (3) Correlation between reading rate and oculomotor dysfunction in NSBVA and (4) changes in BV parameters and reading rate, between non-intervention and intervention group post-vision therapy.

Statistical analysis

The data was analyzed using Microsoft Excel, 2007 and SPSS software version 17.0. The normality of the data was checked by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Since the data was found to be non-normally distributed, appropriate non-parametric statistics were used to represent the data. Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the parameters between normal BV and NSBVA. Effect size (Cohen's D, 1988)20 was calculated to represent the magnitude of difference between the groups. The guidelines proposed by Cohen (1988) for independent samples were used to interpret the results (0.1–0.29 small, 0.3–0.49 medium and ≥0.5 large). Spearman's correlation was used for comparison of DEM ratio and the reading rate. Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare the changes in parameters pre- and post-intervention in the non-intervention and intervention group. p < 0.05 was set as the cut-off for statistical significance.

Results

The mean (SD) age of the subjects was 15 (±2.1) years.

Distribution of refractive error

Out of the 96 subjects, 23 (24%) children had refractive error; astigmatism was found in 10 (43.5%) (range −0.50 DS to −3.50 DS), myopia in 8 (34.7%) (range −0.75 DS to −15.75 DS) and hyperopia in 5 (21.7%) children (range +0.50 DS to +5.00 DS).

Frequency of binocular vision anomalies

Among the 94 children, binocular vision (BV) anomalies were found in 59 children (62.8%) out of which, 46 had non-strabismic BV anomalies (NSBVA) (78%) and 13 had strabismus (22%). Six children had other ocular pathologies (6.4%) and 9 (9.6%) children were found to be uncooperative for the BV assessment and were not included for the study. Twenty children (21.3%) had normal binocular vision (NBV). Among strabismic BV anomalies, exotropia was found in 10 children, esotropia in 2 children and there was a single case of Duane's syndrome.

Among all NSBVA (n = 46), accommodative infacility (AIF) was found in 31 children (68%), followed by convergence insufficiency (CI) in 11 children (25%), divergence excess (DE) and fusional vergence dysfunction (FVD) in 1 child each (2%) and combination of convergence insufficiency and accommodative infacility were found in 2 children (5%).

BV parameters among normal BV and NSBVA group are presented in Table 2. The parameters of comparison include near point of convergence (NPC) break and recovery, negative fusional vergence (NFV) break and recovery values for distance and near, positive fusional vergence (PFV) break and recovery values for distance and near, near point of accommodation (NPA) and accommodative facility (AF) – monocular and binocular values. Mann–Whitney U test revealed significant difference in NPC break and recovery values, and near PFV break and recovery and monocular and binocular AF between children with normal BV and NSBVA (p < 0.001). The median (IQR) VR-QOL scores of the NSBVA group was 8 (1–11.75) and that of the children with normal BV was 3 (4–11) (Mann–Whitney U test, p > 0.05).

Table 2.

Binocular vision parameters among normal and NSBVA group.

| Parameter | Normal BV (n = 20) Median values with inter-quartile range in brackets |

NSBVA (n = 46) Median values with inter-quartile range in brackets |

p-Value (Mann–Whitney U test) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distance NFV break (in PD) | 8 (6–10) | 8 (6–10) | >0.05 |

| Distance NFV recovery (in PD) | 6 (4–8) | 6 (4–8) | |

| Near NFV break (in PD) | 17 (16–20) | 16 (14–20) | |

| Near NFV recovery (in PD) | 14 (14–16) | 14 (11.50–16.0) | |

| Distance PFV break (in PD) | 16 (12–19.50) | 14 (10.0–18.50) | |

| Distance PFV recovery (in PD) | 10 (8–17) | 10 (8.0–15.25) | |

| Near point of accommodation – OD (in D) | 14.30 (12.5–16.7) | 12.5 (11.1–14.3) | |

| Near point of accommodation – OS (in D) | 14.30 (12.5–16.7) | 14.30 (11.1–15.72) | |

| NPC break (cm) | 7 (5–8) | 9 (7.0–10.25) | 0.005 |

| NPC recovery (cm) | 8 (6–9) | 10 (8.0–11.25) | 0.006 |

| Near PFV break (in PD) | 30 (25–35) | 25 (14–30) | 0.024 |

| Near PFV recovery (in PD) | 20 (16–35) | 19 (11.5–21.25) | 0.048 |

| AF OD (cpm) | 11 (10–12) | 4 (2–6) | <0.0001 |

| AF OS (cpm) | 11 (10–12) | 4 (1–6) | |

| AF OU (cpm) | 11 (10.63–12) | 6 (3.50–9.25) |

Unit: cm, centimetre; PD, prism dioptre; D, dioptre; cpm, cycle per minute.

NPC, near point of convergence; NFV, negative fusional vergence; PFV, positive fusional vergence; NPA, near point of accommodation; OD/OS/OU, oculus dexter/oculus sinister/oculus uterque; AF, accommodative facility.

DEM scores in normal and NSBVA

In the normal BV group, 5 children (25%) had normal oculomotor function (Type 1), 3 children each (15%) had horizontal scanning problem (Type 2) and automaticity difficulty (Type 4) and 9 children (45%) had normal horizontal and vertical time but high ratio when compared to the normative test data provided for the age. None of the normal children had a Type 3 DEM typology.

In the NSBVA group, 8 children (18%) had normal oculomotor function (Type 1), 5 children (11%) had horizontal scanning (Type 2), 8 children (18%) had automaticity problem (Type 3), 9 children (20%) had both scanning and automaticity difficulty (Type 4) and 15 children (33%) had normal horizontal and vertical time with high ratio.

The horizontal (H) and vertical (V) time in seconds for DEM test were compared between Normal and NSBVA group. There was no significant difference in horizontal scores between normal BV and NSBVA whereas vertical time revealed significant difference between the two groups as shown in Table 3 (Mann–Whitney U test; p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Developmental eye movement (DEM) test time (in seconds) among Normal BV and NSBVA group.

| DEM test | Median (IQR) | p-Value (Mann–Whitney U test) |

|---|---|---|

| Horizontal DEM time normal BV | 43.5 (34.50–47.91) | >0.05 |

| Horizontal DEM time NSBVA | 48.6 (37–64.86) | |

| Vertical DEM time normal BV | 34 (30.75–37) | 0.039 |

| Vertical DEM time NSBVA | 40 (32–53) |

Reading parameters among normal and NSBVA

The median (IQR) of reading rate among normal and NSBVA group are presented in Table 4. The median reading rate of NSBVA group was lesser compared to children with normal binocular vision, and these results were not statistically significant (Mann–Whitney U test, p > 0.05).

Table 4.

Reading rate comparison among normal and NSBVA group.

| Group | Median (IQR) In words/min |

p-Value Mann–Whitney U test |

|---|---|---|

| Normal (n = 20) | 62 (47–84) | >0.05 |

| NSBVA (n = 46) | 49.5 (26.25–90.5) |

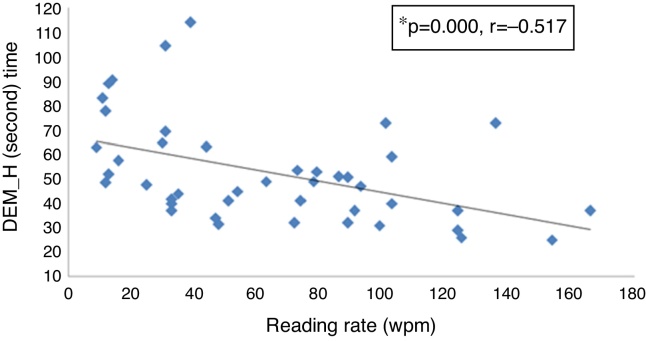

The correlation between reading rate and DEM horizontal scores were analyzed using Spearman correlation. Reading rate in words/min (wpm) was found to be higher in children (n = 43) who took less time in Developmental Eye Movement (DEM) test for horizontal task (r = −0.517, p ≤ 0.0001) as shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Correlation between reading rate and DEM (horizontal scores). *Spearman correlation; r: coefficient of correlation; wpm: words per minute; DEM_H: Developmental Eye Movement Horizontal scores.

Changes in BV parameters before and after VT

There was no statistically significance difference in the mean age of the non-intervention and intervention group (Mann–Whitney U test, p > 0.05). In the intervention group (n = 24), 15 subjects had AIF, 7 subjects had CI, and 1 each had FVD and DE. The changes in BV parameters in the overall NSBVA are depicted in Table 5. Except NFV, all the BV parameters showed statistical and clinically significant difference post-VT compared to baseline, whereas in the non-intervention group, the changes were not statistically significant. Large effect size for the treatment was observed for parameters of AF and PFV, and medium effect size was observed for NPC and NPA. In the intervention and non-intervention group, the DEM horizontal and vertical time did not differ pre- and post-assessment (p > 0.05). Similar trend was observed for reading rate and VR-QOL scores.

Table 5.

Pre- and post-BV parameters in the control and intervention group.

| Parameter | Non-intervention group (n = 22) |

Intervention group (n = 24) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-VT Median (IQR) |

Post-VT Median (IQR) |

*p-Value | Pre-VT Median (IQR) |

Post-VT Median (IQR) |

p-Value Wilcoxon signed rank test |

|

| NPC break (cm) | 9.50 (7–12) | 10 (5–12) | >0.05 | 8 (7–9) | 7 (6–8) | 0.008 |

| NPC recovery (cm) | 10.50 (8.00–12.50) | 11 (6–14) | 9 (8–11) | 8 (7–9) | 0.002 | |

| Distance NFV break (in PD) | 8 (6–10) | 8 (6–10) | 8 (6–12) | 8 (6–12) | >0.05 | |

| Distance NFV recovery (in PD) | 6 (4–8) | 6 (4–6) | 6 (4–10) | 6 (4–10) | ||

| Near NFV break (in PD) | 14 (12–18) | 16 (12–18) | 18 (16–20) | 20 (14–25) | ||

| Near NFV recovery (in PD) | 12 (10–14) | 12 (8–14) | 14 (12–18) | 16 (10–20) | ||

| Distance PFV break (in PD) | 14 (10–20) | 18 (12–20) | 14 (10–18) | 30 (25–30) | <0.0001 | |

| Distance PFV recovery (in PD) | 10 (8–16) | 12 (8–16) | 10 (8–14) | 20 (14–20) | 0.001 | |

| Distance NFV break (in PD) | 25 (14–30) | 20 (12–40) | 25 (14–30) | 40 (30–45) | <0.0001 | |

| Distance NFV recovery (in PD) | 18 (12–25) | 16 (10–25) | 20 (10–20) | 30 (20–45) | <0.0001 | |

| AF OD (cpm) | 4 (2–5) | 2.50 (1–5) | 2 (2–4) | 12 (11–15) | <0.0001 | |

| AF OS (cpm) | 3.50 (1–5) | 4 (1.50–5.00) | 2.50 (1–4) | 12.5 (11.50–15.00) | <0.0001 | |

| AF OU (cpm) | 4 (2–5) | 4 (2–5) | 3.50 (1–5) | 11.50 (10–14) | <0.0001 | |

| NPA OD (D) | 14.3 (11.10–15.40) | 12.50 (10.00–14.30) | 0.018 | 11.8 (11.10–14.30) | 14.3 (11.10–16.70) | 0.008 |

| NPA OS (D) | 14.3 (11.80–15.40) | 11.1 (10.00–16.70) | 0.009 | 12.5 (11.10–14.30) | 14.3 (11.10–16.70) | 0.014 |

Unit: cm, centimetre; PD, prism dioptre; D, dioptre; cpm, cycle per minute.

NPC, near point of convergence; NFV, negative fusional vergence; PFV, positive fusional vergence; NPA, near point of accommodation; AF, accommodative facility; IQR, inter quartile range.

Following VT, statistically significant changes in NPC break and recovery and near PFV break and recovery values were observed in CI (n = 7) and the monocular and binocular AF showed statistically significant difference pre- vs. post-VT in AIF (n = 15) (Wilcoxon signed rank test p < 0.05).

Discussion

This study reports a high frequency of NSBVA (63%) in children with LD. Accommodative infacility (AIF) was highly prevalent (67%), followed by convergence insufficiency (CI) (25%). Similar trend has been reported in other populations5, 6 wherein, the prevalence of AIF ranged between 26 and 31.7% and CI between 14 and 38%. In contrary to the previous literature, we did not see subjects with accommodative insufficiceny in our sample.5, 6, 9, 10, 11, 15

We also observed a higher frequency of refractive errors (24%) in this special population, with a high frequency of astigmatism in 44% of the study subjects. Similar results have been reported by Vora et al.21 who showed a high frequency of astigmatism (27%) followed by myopia (24.3%) and hyperopia (18.6%). Statistical and clinically significant differences were seen in near PFV break and recovery, NPC break and recovery and monocular and binocular accommodative facility pre- and post-VT in the intervention group. As this difference was not seen in the non-intervention group, the achieved improvement could be attributed to the true effect of VT beyond learning and test–retest effects. As convergence insufficiency and accommodative infacility contribute to 88% of the NSBVA in the intervention group, these results are limited to these specific types of NSBVA.

In children with LD, the DEM horizontal time was prolonged compared to vertical time in both normal BV and NSBVA group, indicating that children with SLD have deficits in saccadic eye movements, a finding in agreement with previous studies.9 The reading rate and DEM horizontal time was negatively correlated suggesting the association between increased horizontal times with reduced reading rate observed in this sample. We also found high vertical time in NSBVA group when compared to subjects with normal BV that signifies that the automaticity difficulty was also common among children with NSBVA. In our study, though the reading rate of children with NSBVA was higher than children with NBV, these results did not reach statistical significance. This could potentially be attributed to the unequal sample size and low power to detect an adequate difference. Similarly we did not observe statistically significant improvements in VR-QOL scores. One of the limitations with the interpretation of VR-QOL score is that, it was filled by the class teacher based on inputs from the child. Though teacher or parent administration is the recommended mode in special population and younger children,18 it also poses risk due to the rater administered variables such as translation, and interpretation. This needs further exploration and thus may not reflect the true symptomology of the children.

Our study confirms that children with specific LD have higher frequency of NSBVA. It has been reported that five out of the nine criteria for ADHD in DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) overlap with the symptoms of CI such as loss of concentration when reading or reading slowly, failure to complete assignments and trouble of concentration in class.22 This study in children with specific learning disorders emphasize the need for screening for binocular vision anomalies.

Vision therapy plays a significant role in improving the binocular vision parameters in this special population. Therefore we recommend a comprehensive BV assessment to be part of the vision care protocol for children with SLD, and vision therapy should be recommended for children with NSBVA.

The strength of our study includes a structured VT protocol with a non-intervention control group. Though this is not the best research approach, and a placebo treatment group is recommended as control in randomized controlled trials, this experimental study proves that vision therapy improves binocular vision parameters which are beyond test–retest and learning effect. We also provided vision therapy at the school premises to ensure compliance with therapy and loss to referral follow-up. The limitation of our study include an absence of masked examiner as the same optometrist was involved in the administration of VT and assessment of BV parameters pre and post-VT. But it was made sure that baseline BV parameters were not looked into until post-VT assessment was carried out. Also the pre-post-vision therapy comparison in each subgroup of NSBVA is ideal to comment about the efficacy of vision therapy for each specific anomaly but as the sample size of the subjects were lesser in the sub groups, we have represented this as overall NSBVA. To conclude, NSBVA are the commonest among the spectrum of ocular disorders in children with specific learning disorders. These anomalies could potentially be an added hindrance to the reading difficulty in this special population. Vision therapy plays an important role in improving the binocular vision parameters.

Financial disclosures

None.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Hammill D.D., Leigh J.E., McNutt G., Larsen S.C. A new definition of learning disabilities. Learn Disabil Q. 1988;11:217–223. doi: 10.1177/002221948702000207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association [APA] 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; Washington, DC: 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mogasale V.V., Patil V.D., Patil N.M., Mogasale V. Prevalence of specific learning disabilities among primary school children in a south Indian city. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79:342–347. doi: 10.1007/s12098-011-0553-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willows D.M. A framework for understanding learning difficulties and disabilities. In: Garzia R.P., editor. Vision and Reading. C.V. Mosby; St. Louis: 1996. pp. 229–247. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grisham D., Powers M., Riles P. Visual skills of poor readers in high school. Optometry. 2007;78:542–549. doi: 10.1016/j.optm.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muzaliha M.N., Buang N., Adil H. Visual acuity and visual skills in Malaysian children with learning disabilities. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;6:1527–1533. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S33270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dusek W.A., Pierscionek B.K., McClelland J.F. An evaluation of clinical treatment of convergence insufficiency for children with reading difficulties. BMC Ophthalmol. 2011;11:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-11-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kedzia B., Tondel G., Pieczyrak D., Maples W.C. Accommodative facility test results and academic success in Polish second graders. J Am Optom Assoc. 1999;70:110–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palomo-Álvarez C., Puell M.C. Accommodative function in school children with reading difficulties. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246:1769–1774. doi: 10.1007/s00417-008-0921-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palomo-Álvarez C., Puell M.C. Binocular function in school children with reading difficulties. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010;248:885–892. doi: 10.1007/s00417-009-1251-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dusek W., Pierscionek B.K., McClelland J.F. A survey of visual function in an Austrian population of school-age children with reading and writing difficulties. BMC Ophthalmol. 2010;10:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-10-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial Study Group Randomized clinical trial of treatments for symptomatic convergence insufficiency in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1336–1349. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.10.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palomo-Álvarez C., Puell M.C. Effects of wearing yellow spectacles on visual skills, reading speed, and visual symptoms in children with reading difficulties. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251:945–951. doi: 10.1007/s00417-012-2162-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans B.J. The underachieving child. Ophthal Physiol Opt. 1998;18:153–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marran L.F., Land P.N., Nguyen A.L. Accommodative insufficiency is the primary source of symptoms in children diagnosed with convergence insufficiency. Optom Vis Sci. 2006;83:281–289. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000216097.78951.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scheiman M., Wick B. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; USA: 2014. Clinical Management of Binocular Vision: Heterophoric, Accommodative and Eye Movement Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garzia R.P., Richman J.E., Nicholson S.B. A new visual–verbal saccade test; the Developmental Eye Movement test (DEM) J Am Optom Assoc. 1990;61:124–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bakar N.F.A., Hong C.A., Pin G. COVD-QOL questionnaire: an adaptation for school vision screening using Rasch analysis. J Optom. 2012;5:182–187. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramani K.K., Police S.R., Jacob N. Impact of low vision care on reading performance in children with multiple disabilities and visual impairment. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62:111–115. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.111207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pallant J. 3rd ed. Allen & Unwin; Australia: 2001. SPSS Survival Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vora U., Khandekar R., Natrajan S., Al-Hadrami K. Refractive error and visual functions in children with special needs compared with the first grade school students in Oman. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2010;17:297–302. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.71590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Granet D.B., Gomi C.F., Ventura R., Miller-Scholte A. The relationship between convergence insufficiency and ADHD. Strabismus. 2005;13:163–168. doi: 10.1080/09273970500455436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]