Abstract

The magnetization reversal induced by spin orbit torques in the presence of Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction (DMI) in perpendicularly magnetized Ta/CoFeB/MgO structures were investigated by using a combination of Anomalous Hall effect measurement and Kerr effect microscopy techniques. By analyzing the in-plane field dependent spin torque efficiency measurements, an effective field value for the DMI of ~300 Oe was obtained, which plays a key role to stabilize Néel walls in the film stack. Kerr imaging reveals that the current-induced reversal under small and medium in-plane field was mediated by domain nucleation at the edge of the Hall bar, followed by asymmetric domain wall (DW) propagation. However, as the in-plane field strength increases, an isotropic DW expansion was observed before reaching complete reversal. Micromagnetic simulations of the DW structure in the CoFeB layer suggest that the DW configuration under the combined effect of the DMI and the external field is responsible for the various DW propagation behaviors.

Introduction

Recently, current-induced highly-efficient magnetization reversal1–3 and fast domain wall (DW) motion4–6 by utilizing spin orbit torques (SOT)7 have drawn much attention for their potential application in magnetic memory8–10 and logic devices11. In heavy metal (HM)/ferromagnetic (FM)/Insulators (I) heterostructures with broken inversion symmetry, an in-plane current may induce SOT with both damping-like and field-like terms, resulting from spin Hall (SHE)3 and Rashba1 effects. Although the field-like term was non-negligible in most of the HM/FM/I structures, both theoretical and experimental works have suggested that the SHE mechanism by itself was sufficient to explain the current-induced magnetization switching and DW motion in these structures3–6,12,13. In the SHE regime, the spin current originating from the spin dependent scattering in the HM layer penetrates through the HM/FM interface and exerts a torque on the FM layer, which may induce deterministic magnetization switching of the FM layer3. The application of SOT-induced magnetization switching in magnetic random access memory (MRAM) prevents damage to the insulating layer from the large writing current, which remains a significant challenge for spin-transfer torque MRAM8,9. However, in the HM/FM/I structures with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy (PMA), theoretical and experimental work have verified that an external in-plane magnetic field is required for deterministic switching to break the symmetry along the current direction3,14. Although this in-plane field may in principle be supplied by an integrated bias permanent magnet, it is undesirable from a practical point of view15. Therefore, researchers have opted to reduce or eliminate the required external in-plane magnetic field by engineering the film stacks15–18.

From another perspective, understanding the role of the in-plane magnetic field in SOT-induced magnetization switching is equally as important for the application of SOT effect. Initially, a macrospin model was used to explain the role of the in-plane magnetic field along the current direction, which is required to break the symmetry of current-induced damping-like field with respect to the “up” or “down” magnetization states3. However, for devices of micron dimensions, a macrospin description is clearly inadequate to provide an accurate quantitative understanding of the reversal process because of the presence of the spatially nonuniform reversal process3. The current-induced DW depinning model proposed by Lee et al.14 gave a better understanding of the magnetization reversal process and the role of the in-plane field in SOT-induced magnetization switching. They suggested that the function of the field was to orient the magnetic moments within the DW to align a significant component parallel to the current flow, thereby allowing the torque from the SHE to produce a perpendicular equivalent field that can expand a reversed domain in all lateral directions. However, that does not explain why experimentally the required in-plane field for current-induced deterministic switching is only approximately 10%-25% of the effective field caused by the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction (DMI). In addition, the subsequent magneto-optical Kerr effect (MOKE) study of current-induced switching in HM/FM/I structures confirmed the DW depinning process driven by SOT. Nevertheless, how the DMI affects the current-induced DW propagation is still unclear. Moreover, the results from experimental observations of DW propagation process in similar film stacks are inconsistent19–23. An understanding of nucleation and SOT-induced DW propagation in HM/FM/I structures with DMI therefore remains incomplete.

In our study, a systematic analysis of SOT-induced magnetization switching in Ta/CoFeB/MgO structures under various in-plane magnetic fields was performed. The current-induced DW propagation process under various in-plane magnetic fields was observed using MOKE microscopy. Finally, by micromagnetic simulations of the DW structure with the inclusion of DMI effects, we identified the origin of the current-induced asymmetric DW propagation and the role of the in-plane field in SOT-induced magnetization reversal.

Results

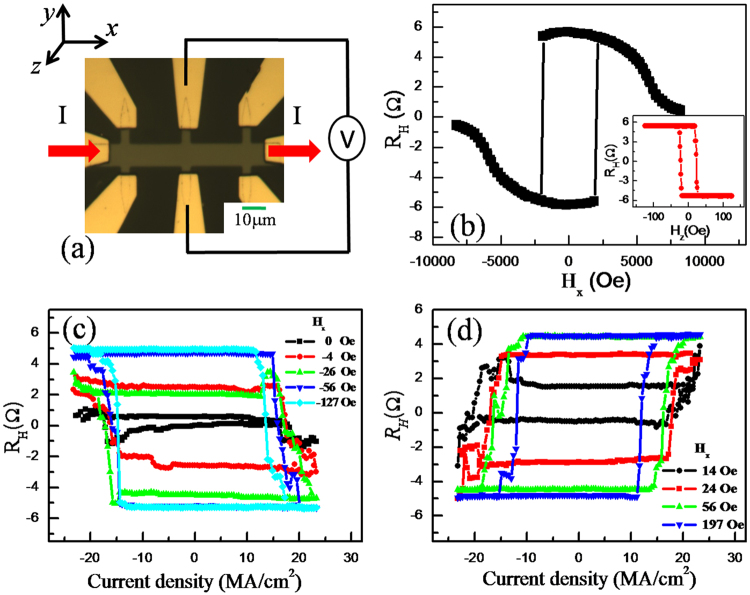

A film stack with the structure of Ta (3 nm)/Co20Fe60B20 (1.3 nm)—hereafter denoted as CoFeB/MgO (1 nm)/Ta (1 nm) layers was deposited at room temperature on thermally oxidized Si substrates by using a magnetron sputtering system with a base pressure below 1.0 × 10−7 Torr. The film stack was subsequently patterned into eight-terminal Hall bar devices of differing dimensions by standard photolithography and ion milling techniques. A top view photomicrograph of a typical device is shown in Fig. 1(a). The current-induced magnetization switching was characterized from anomalous Hall effect (AHE) measurements and MOKE microscope images taken at room temperature. In the AHE measurement, the Hall resistance (RH), which is proportional to the perpendicular magnetization of CoFeB in the structures, was measured using a constant 100-μA bias current. A constant RH value was subtracted from the original data to remove the offset of RH resulting from the welding-spot misalignments of the voltage terminals. The square AHE loops shown in the inset of Fig. 1(b) indicate that the device has a strong PMA. The effective magnetic anisotropy field (Hk eff) can be evaluated by fitting to the hard-axis magnetic field dependence of RH, which is around 7 kOe (Fig. 1(b)).

Figure 1.

Anomalous Hall effect (AHE) and current-induced switching in the Ta/CoFeB/MgO structure. (a) Top-view photomicrograph of a device showing the configuration for AHE measurements, and coordinate system. (b) In-plane and out-of-plane (inset) magnetic field dependence of the Hall resistance RH. (c) and (d) show the measurement results for current-induced magnetization switching from RH values for various constant in-plane magnetic fields Hx. In measurements, a small current of 0.1 mA between two consecutive current pulses was used to detect the magnetization orientation in the devices.

Next, we investigated the current-induced magnetization switching under different in-plane magnetic fields (Hx) in a 10-μm-wide device. In this experiment, a series of current pulses with pulse width of 1 ms was applied to the devices to switch the magnetization. Between two consecutive pulses, a small current of 0.1 mA was used to determine the magnetization orientation. Figure 1(c,d) shows the current-induced magnetization switching under a constant Hx with different amplitude and direction. When an Hx of above 50 Oe is applied, the pulse current induces a deterministic magnetization switching, with positive current favoring RH > 0. If Hx is reversed, the current-driven transitions are reversed, with positive current now favoring RH < 0. Whereas only incomplete magnetization switching was observed with |Hx| < 50 Oe and almost no switching occurs with |Hx| < 10 Oe.

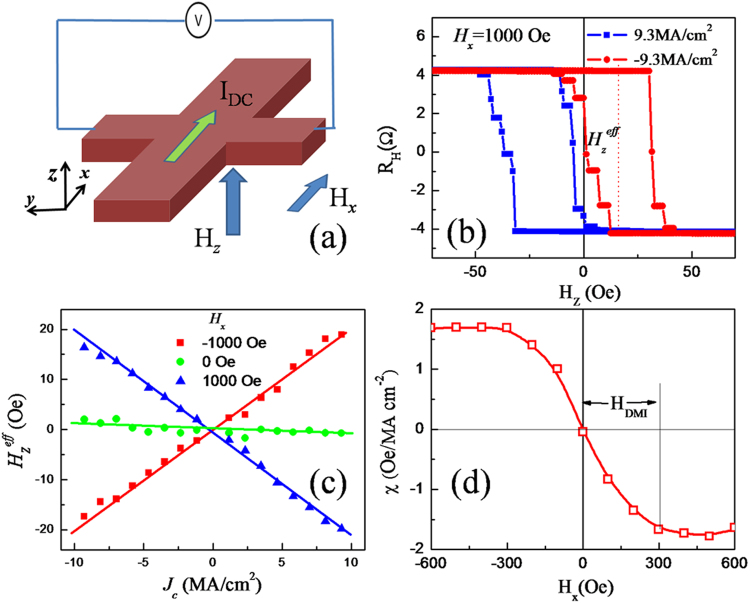

To understand the microscopic mechanism of SOT-induced magnetization switching under various Hx, the function of the DMI at the HM/FM interface needs to be considered. Previous works have suggested that the chiral Néel domain walls (DWs) can be stabilized by the DMI in ultrathin films lacking inversion symmetry5,6,24,25. The current-induced magnetization switching and DW motion in HM/FM bilayers then can be explained by a SHE + DMI scenario5,14. Because the spin Hall angle of Ta is negative2, the SHE effective field produced by a negative current (−x direction) can be expressed as 14. As a result, the vertical component of the equivalent field of the SHE is Hzeff = HSHmx. For chiral Néel DWs, the perpendicular component of the current-induced effective field (Hzeff) at the DW can lead to DW motion but not domain expansion in the absence of Hx because of the opposite signs of Hzeff for up-down and down-up DWs. However, by applying a large enough Hx to overcome the effective DMI field (HDMI), the DW moments in the Néel-type walls are realigned parallel to Hx. In this case Hzeff points along the same direction for both up-down and down-up walls and therefore facilitates both domain expansion and contraction, ultimately fulfilling the criteria for deterministic current-induced switching14. Conversely, in measuring the AHE with large current, current-induced Hzeff at the DW may compete with the applied perpendicular field (Hz) and induce a considerable shift along the Hz axis in the RH vs Hz loops21. Then the effective DMI field can be acquired by measuring the spin torque efficiency (i.e. Hzeff per current density) as a function of Hx. As schematically shown in Fig. 2(a), we measured the RH vs Hz loops in the Hall-bar devices as a function of applied dc current density (Jc) and Hx. Jc was obtained by the total current Representative RH vs Hz loops with Hx = 1000 Oe and Jdc = ±9.3 MA/cm2 are shown in Fig. 2(b). The opposite loop shifts along the Hz axis of the hysteresis loops corresponding to opposite polarities of Jc indicate the presence of a current-induced Hzeff generated from the damping-like torque. From the current-induced Hzeff plotted against Jc with different amplitudes and polarities, as shown in Fig. 2(c), the linear variation provides a good estimate of Hzeff /Jc. To verify that this measured Hzeff indeed stems from the SHE, we also measured the Hzeff–Jc curves with Hx = −1000 and 0 Oe. By reversing the polarity of Hx, the slope of Hzeff /Jc is also reversed. This is consistent with the prediction from the SHE + DMI scenario5,14. In addition, a near-zero Hzeff /Jc value at Hx = 0 Oe coincides also with the fact that no current-induced switching happening at zero Hx [Fig. 1(c)]. In Fig. 2(d), we summarized the measured effective field per current density (χ = Hzeff/Jc) as a function of Hx. We find that χ increases quasi-linearly with Hx and saturates at Hx ≈ ±300 Oe, at which the DW moment in the Néel-type walls realign parallel to Hx, and therefore the |Hzeff| attains a maximum. Based on this model, we estimate χSHE ≈ 1.7 Oe/(MA/cm2) and |HDMI| ≈ 300 Oe for Ta (3)/CoFeB (1.3)/MgO(1) from the saturation value of χ and the saturation field, respectively. The low χSHE indicates a corresponding low spin Hall angle (0.06) of the Ta layer, but it is consistent with our results measured using harmonic voltage method26. The DMI constant (D) was estimated from HDMI = D/(μ 0MSΔ)27, where Ms is the saturation magnetization of the CoFeB layer (1200 emu/cc) and Δ the DW width obtained from , A = 16 pJ/m, Keff = 4.2 × 105 J/m3. The calculated DMI constant is around 0.22 mJ/m2, which is within the range of previously reported values in similar magnetic heterostructure systems25,28,29. According to the q-Φ model proposed by André Thiaville et al.27, the critical value of DMI to stabilize the chiral Néel DWs is given by , where Δ is the DW width and K is the magnetostatic “shape” anisotropy that favors the Bloch wall, related to the “demagnetizing coefficient” Nx of the wall by . The calculated Dc is around 0.16 mJ/m2 for our Ta/CoFeB/MgO films, which confirm that the DMI in our films is high enough to stabilize the chiral Néel DWs.

Figure 2.

Measurements of spin orbit torque efficiency and DMI effective field. (a) Schematic of AHE measurements with an in-plane field Hx applied. (b) AHE loops with dc currents density Jc = ±9.3 MA/cm2 and an in-plane bias field Hx = 1000 Oe applied. (c) Hzeff as a function of Jc under different bias fields. (d) Measured effective χ as a function of applied in-plane field.

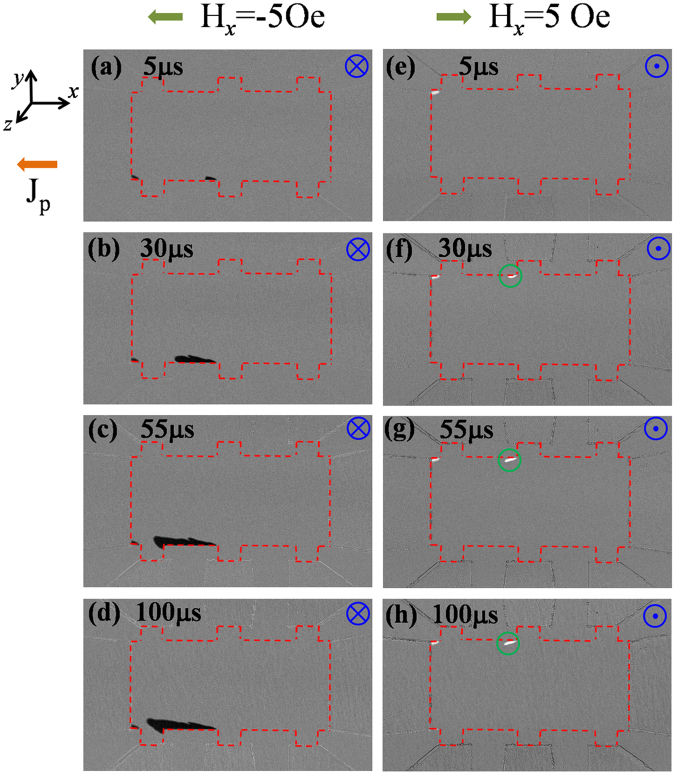

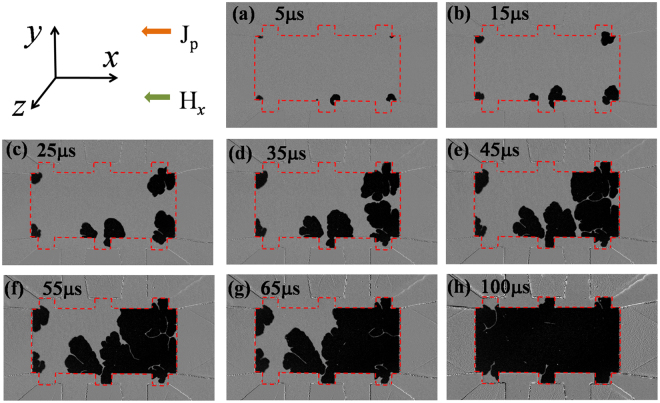

To gain insights in the processes resulting in the current-induced magnetization reversal, we performed microscope imaging of the magneto-optical Kerr effect on a device with the same film stack structure but different dimensions (80 μm in width). In this experiment, the device was initially saturated by applying a perpendicular magnetic field (Hz), either up or down; Hz was then removed and a constant Hx applied. A series of short current pulses (5 μs in duration for each pulse) was applied to the device to produce SOTs, thereby inducing nucleation with reversed magnetization and subsequent DW propagation in the magnetic layer. Immediately following each pulse, MOKE images were taken to monitor the magnetization status of the CoFeB layer. First, this procedure was performed with a pulse current density (Jp) of 10 MA/cm2 at Hx = ±5 Oe. The corresponding MOKE images after applying the current pulses were shown in Fig. 3. In the images, the magnetic area of the device exposed under the microscope is outlined (red dotted lines) as a guide. Note that the reversed domains always nucleate along the bottom edge of the stripe after the first current pulse for the down-magnetized case (the left column in Fig. 3). If the initial out-of-the-plane magnetization state is reversed, nucleation is seen to occur on the top edge instead (Fig. 3(e,f)). In all observations, the Oersted field is always anti-parallel to the initial magnetization. This strongly suggests that, for small Hx, the nucleation location is determined by the Oersted field generated by the in-plane charge current flowing along the device. From a numerical calculation of the Oersted field produced by the current20, the vertical component of the Oersted field is found to peak but with opposite polarity at the two long edges of the device. Its peak value at the edges is about 7.2 Oe with Jp = 10 MA/cm2 for 80-μm-wide devices. As the Oersted field is still lower than the measured nucleation field (i.e., coercivity) of the sample of about 15 Oe, we believe that the effective field produced by the SOT also contributes in nucleating the reversed domain. After applying several pulses, the left-hand side of the DW propagates slowly along the charge current direction for both down-magnetized (left column) and up-magnetized (right column) configurations. However, we did not observe transverse and rightward DW propagation after applying 20 pulses (100 μs duration in total) for both cases. The mechanism underlying the asymmetric DW propagation induced by the current is discussed in detail below after analyzing the DW structure and current-induced SHE effective field in the structure.

Figure 3.

MOKE images of a Hall bar device after applying a series of current pulses (5 μs in duration and 10 MA/cm2 in current density for each pulse) in the presence of a small Hx of ±5 Oe. Before applying the current pulses, the device was pre-saturated with (left column) a downward magnetization (right column) upward magnetization. The direction of Hz for pre-saturating the sample and the applied total pulse duration before taking the images are given at the top right and top left of each panel, respectively. The green circles in the right column marked the area with tiny DW propagation.

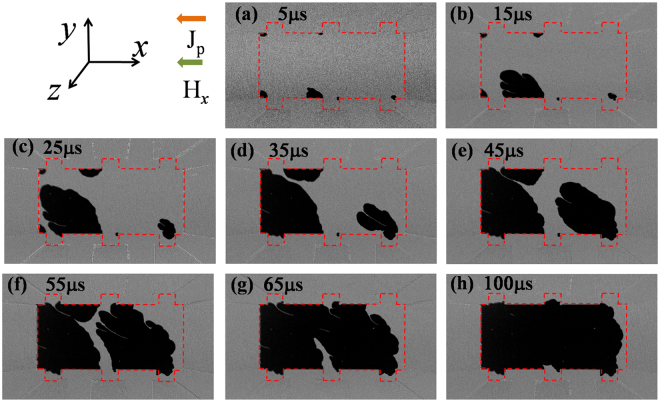

When |Hx| was increased to 145 Oe, a different current-induced domain nucleation and DW propagation process was observed. The domains are nucleated at both top and bottom edges of the stripe after the first current pulse, as shown in Fig. 4(a). This indicates that the SOT effective field alone is sufficient to nucleate domains in contrast to the case with Hx = ±5 Oe where the Oersted field played a significant role. In accordance with the theory of SHE, the vertical component of the equivalent spin Hall field is HSH,z = HSHmx, where mx is the magnetization component collinear with the current14. Because of inhomogeneity in film thickness and anisotropy in ultrathin CoFeB films30, with a medium Hx (145 Oe) applied, the moment may be tilted and induces a considerable mx in the area with weak PMA, and thus the corresponding HSH,z induces nucleation of the reversed domain, assisted by thermally activated processes14. In addition, we noticed that the domains always nucleate near the junction of Hall probe and the micro-stripe which is likely due to the higher demagnetization energy and reduced Hkeff31. We believe the effect of width modulation on current density distribution also contribute to the nucleation at the crosspoints of the Hall probes and the micro-stripe. Differing from the case with small Hx, we observed a distinct transverse DW expansion induced by the current pulses. However, the DW motion from the bottom to top edge is much faster than that in the opposite direction, indicating that the Oersted field cannot be ignored completely. Finally, with a medium Hx applied, much of the area in the Hall bar was reversed after 20 current pulses [Fig. 4(h)], which corresponds to a deterministic switching in the Fig. 1. These results also demonstrate that the required Hx does not need to be larger than HDMI for deterministic current-induced switching, which may depend on the nucleation location of the reversed domain in the devices.

Figure 4.

Same as Fig. 3 but in the presence of a medium Hx = −145 Oe. The device was pre-saturated with a downward magnetization and negative current flowing leftward.

With Hx = −1kOe and Jp = 10 MA/cm2, the current-induced magnetization reversal was completed in a single pulse because of the large HSH,z and DW motion velocity. For further insight into this reversal process with large Hx, we reduced Jp to 5.5 MA/cm2 and observed the reversal process using MOKE imaging (Fig. 5). Similar to a medium Hx, domains had nucleated on both edges of the stripe near the voltage electrodes. Although the expansion of the reversed domain exhibited irregularity due to inhomogeneity in the films, we did not see obvious directionality in the DW motion in the transverse direction; this differs from that with small and medium Hx (Figs 3 and 4). We observed an almost isotropic DW propagation induced by the current pulses and ultimately a complete reversal of the entire magnetic area within 20 current pulses, as shown in Fig. 5(h).

Figure 5.

Same as Fig. 3 but in the presence of a large Hx of −1000 Oe. The device was pre-saturated with a downward magnetization and negative current flowing leftward. The magnitude of current density was reduced to 5.5 MA/cm2 to observe the current-induced reversal process.

Discussion

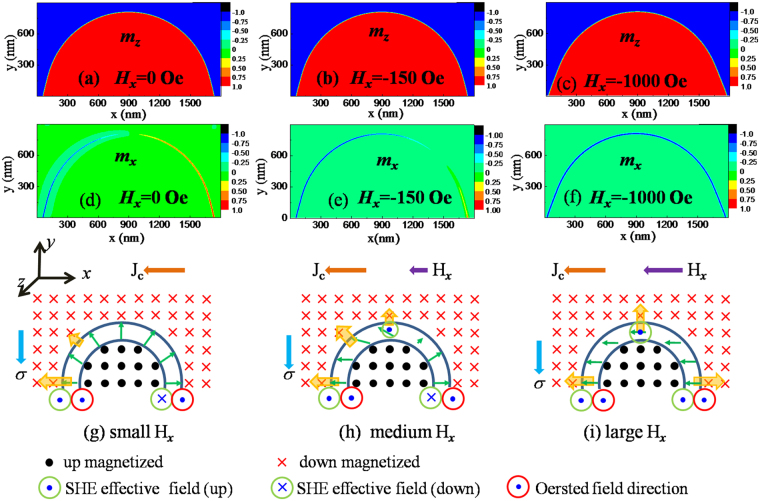

To understand the difference in the current-induced DW propagation process under the various Hx, we performed a micromagnetic simulation on the DW structure of the device. We chose a 900 × 1800 nm rectangular area, in which a semi-circular reversed domain formed at the bottom edge with magnetization pointing up (+z direction) and other area with magnetization pointing down (−z direction). Figure 6(a–f) shows the z-component (mz) and x-component (mx) of the magnetic moment obtained from simulations for various Hx. Because Hx is much smaller than the PMA of the films, it did not significantly affect mx and mz in the domains, but rather the orientation of the moment in the DW. Without Hx applied, the distribution of mx [Fig. 6(d)] and my (not shown) in the DW confirmed the Néel wall profile resulting from the DMI. It should be noted that the effect of field-like torque on the spin configuration in DWs was neglected in the simulation because its amplitude (about 22 Oe for the given current density Jp = 10 MA/cm2) is much lower than the HDMI and the in-plane field (Hx).

Figure 6.

Micromagnetic simulation of the DW structure in Ta/CoFeB/MgO structures with DMI effect. (a–f) mz and mx distributions obtained from the simulations for different Hx. (g–i) schematics of the magnetic moment orientation near the DW and corresponding SHE effective field and Oersted field induced by the current.

Following an analysis of the vertical component of the effective SOT field at the DW, the current-induced DW propagation can be explained. According to the previous discussions, the vertical component of the SHE equivalent field produced by a negative current (−x direction) can be expressed as HSH,z = HSHmx. Therefore, HSH,z experienced by the DW depends not only on the amplitude and direction of the current density J, but also on the orientation of the magnetization within the DW. Without Hx, the direction of HSH,z on both sides of the half-circular DW are opposite because of the Néel wall profile, whereas the Oersted field has the same amplitude and direction. As a result, the total effective field is enhanced on the left-hand side of the DW and is canceled on the right-hand side, as illustrated in Fig. 6(g). The enhanced effective field can overcome the pinning field and induce a leftward DW motion, whereas on the right-hand side the DW is still pinned because of the small effective field. In addition, in the top portion of the circular DW, HSH,z is nearly zero because mx is nearly zero and therefore no transverse DW propagation is observed. This is consistent with the experimental observation (Fig. 3)

Figure 6(b,e) and (h) shows the mz and mx values, respectively, obtained from the simulation and a schematic of the corresponding DW magnetization for the medium external field Hx = −150 Oe, which is about half of the measured HDMI corresponding to the experimental conditions in Fig. 4. In this case, the external field is thus not sufficient to overcome the DMI field but does change the orientation of the moment in the DW. We note that the magnetic moments on both sides of the DW retain their original orientation and therefore a leftward DW expansion similar to that without Hx is observed. In the top part of the DW, the non-zero mx may induce a considerable HSH,z and a corresponding transverse DW motion along the y-direction, confirmed by the experimental observations in Fig. 4. Because both longitudinal and transverse DW motion occurs, the reversed domain can expand in both −x and y direction. However, because of the small net effective field at the right-hand side of the DW, no DW motion rightwards is observed and a small magnetic area at the right-hand side of the stripe was not reversed even after 20 current pulses (100 μs), as illustrated in the Fig. 4(h).

With the mz and mx values obtained from simulations and from the corresponding schematic for a large external field Hx = −1000 Oe [Fig. 6(c,f and i)], the applied field fully overcomes HDMI and completely aligns the moment in the DW along the −x direction. Therefore, HSH,z is always pointing up along the DW, which induces an isotropic DW expansion in all lateral directions and ultimately results in complete magnetization reversal. The theoretical expectation is consistent with experimental results (Fig. 5).

In summary, we have studied magnetization reversal driven by SOT and the DMI in the Ta/CoFeB/MgO structure. The results suggest that for as-deposited Ta/CoFeB/MgO structure, the DMI effective field was found to be around 300 Oe, which stabilized the chiral Néel walls. In such a structure, SOT-induced magnetization reversals exhibit different behavior under various Hx. With a small Hx applied, the Oersted field governed the nucleation at an edge of the stripe, and the current-induced DW motion is unidirectional because of the chiral Néel DW. For medium Hx (<HDMI), due to the increase of the spin Hall effective field and the change of DW configuration, the magnetization reversal is fulfilled by the nucleation at both edges of the stripe and current-induced asymmetric DW motion. In applying larger Hx (>HDMI), that overcame the chiral Néel wall and aligned substantially the moment in the DW along the field direction, the spin Hall field expanded the reversed domain in all lateral directions and induced a complete magnetization switching. The results also suggest that the required Hx for SOT-induced complete switching is not necessarily larger than HDMI because of the transverse DW motion with a medium Hx applied.

Methods

Sample preparation

The film stack with the structure of Ta (3 nm)/Co20Fe60B20 (1.3 nm)/MgO (1 nm)/Ta (1 nm) layers was deposited at room temperature on thermally oxidized Si substrates by using a magnetron sputtering system with a base pressure below 1.0 × 10−7 Torr. Ar (5 mTorr) gas was used during the sputtering process. The Ta and CoFeB layers were grown by direct-current sputtering and the MgO layer was grown by radio-frequency sputtering using a ceramic MgO target. The film stack was subsequently patterned into eight-terminal Hall bar devices of differing dimensions by standard photolithography and ion milling techniques. Finally, Al(300 nm)/TiWN(10 nm) electrodes were formed at the ends of the channel and Hall probes.

Micromagnetic simulation

The magnetic moment orientation in the domain and DW was calculated by solving the Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert equation, given as

| 1 |

where is the unit vector along the magnetization, α (=0.3) the damping constant, the unit vector along the thickness direction, Heff the effective field including the exchange, magnetostatic, anisotropy and DMI. The contribution of DMI to the total Heff can be expressed as32:

| 2 |

In the calculation, the cell size is 3 nm × 3 nm × 0.8 nm with a total of 600 × 300 × 1 cells, and an exchange constant of 16 pJ/m was used. The values of other parameters for the simulation were obtained from experimental results: specifically, Ms = 1200 emu/cc, Hk = 22 kOe, DMI = 0.22 mJ/m2, and tCoFeB = 0.8 nm after subtracting the dead layer thickness at Ta/CoFeB interface33.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos 11674142, 51371101 and 51771099) and by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (lzujbky-2017–179). The work done at Nanyang Technological University was supported by an Industry-IHL Partnership Program (NRF2015-IIP001–001) and an A*STAR SERC AME Programmatic Fund (A1687b0033). Partial support from a MOE-AcRF Tier 2 Grant (MOE 2013-T2–2–017) is also acknowledged.

Author Contributions

J.C. conceived the experiments and wrote the manuscript; H.L. and S.C. fabricated the devices, Y.C., T.J., W.G. and Y.Z. performed the measurements, Y.W. and D.W. conducted the micromagnetic simulation; J.C. W.G. and W.L. analyzed the results. All authors read and approved the final version.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jiangwei Cao, Email: caojw@lzu.edu.cn.

Wen Siang Lew, Email: wensiang@ntu.edu.sg.

References

- 1.Miron IM, et al. Perpendicular switching of a single ferromagnetic layer induced by in-plane current injection. Nature. 2011;476:189–193. doi: 10.1038/nature10309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu L, et al. Spin-torque switching with the giant spin Hall effect of tantalum. Science. 2012;336:555–558. doi: 10.1126/science.1218197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu L, Lee OJ, Gudmundsen TJ, Ralph DC, Buhrman RA. Current-induced switching of perpendicularly magnetized magnetic layers using spin torque from the spin Hall effect. Phys Rev Lett. 2012;109:096602. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.096602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miron IM, et al. Fast current-induced domain-wall motion controlled by the Rashba effect. Nat Mater. 2011;10:419–423. doi: 10.1038/nmat3020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emori S, Bauer U, Ahn S-M, Martinez E, Beach GSD. Current-driven dynamics of chiral ferromagnetic domain walls. Nat Mater. 2013;12:611–616. doi: 10.1038/nmat3675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haazen PPJ, et al. Domain wall depinning governed by the spin Hall effect. Nat Mater. 2013;12:299–303. doi: 10.1038/nmat3553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miron IM, et al. Current-driven spin torque induced by the Rashba effect in a ferromagnetic metal layer. Nat Mater. 2010;9:230–234. doi: 10.1038/nmat2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cubukcu M, et al. Spin-orbit torque magnetization switching of a three-terminal perpendicular magnetic tunnel junction. Appl Phys Lett. 2014;104:042406. doi: 10.1063/1.4863407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao WS, et al. Failure and reliability analysis of STT-MRAM. Microelectron Reliab. 2012;52:1848–1852. doi: 10.1016/j.microrel.2012.06.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brink A, et al. Spin-Hall-assisted magnetic random access memory. Appl Phys Lett. 2014;104:012403. doi: 10.1063/1.4858465. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhowmik D, You L, Salahuddin S. Spin Hall effect clocking of nanomagnetic logic without a magnetic field. Nat Nanotechol. 2014;9:59–63. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang M, et al. Spin-orbit torque in Pt/CoNiCo/Pt symmetric devices. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20778. doi: 10.1038/srep20778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez E, Emori S, Beach GSD. Current-driven domain wall motion along high perpendicular anisotropy multilayers: The role of the Rashba field, the spin Hall effect, and the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Appl Phys Lett. 2013;103:072406. doi: 10.1063/1.4818723. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee OJ, et al. Central role of domain wall depinning for perpendicular magnetization switching driven by spin torque from the spin Hall effect. Phys Rev B. 2014;89:024418. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.89.024418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu G, et al. Switching of perpendicular magnetization by spin–orbit torques in the absence of external magnetic fields. Nat Nanotechnol. 2014;9:548–554. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu G, et al. Current-driven perpendicular magnetization switching in Ta/CoFeB/[TaOx or MgO/TaOx] films with lateral structural asymmetry. Appl Phys Lett. 2014;105:102411. doi: 10.1063/1.4895735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.You L, et al. Switching of perpendicularly polarized nanomagnets with spin orbit torque without an external magnetic field by engineering a tilted anisotropy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:10310–10315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1507474112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukami S, Zhang C, DuttaGupta S, Kurenkov A, Ohno H. Magnetization switching by spin-orbit torque in an antiferromagnet–ferromagnet bilayer system. Nat Mater. 2016;15:535–541. doi: 10.1038/nmat4566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhowmik D, et al. Deterministic Domain wall motion orthogonal to current flow due to spin orbit torque. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11823. doi: 10.1038/srep11823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durrant CJ, Hicken RJ, Hao Q, Xiao G. Scanning Kerr microscopy study of current-induced switching in Ta/CoFeB/MgO films with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy. Phys Rev B. 2016;93:014414. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.93.014414. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pai CF, Mann M, Tan AJ, Beach GSD. Determination of spin torque efficiencies in heterostructures with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy. Phys Rev B. 2016;93:144409. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.93.144409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu D, et al. Appl Phys Lett. 2016;109:222401. doi: 10.1063/1.4968785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rojas-Sanchez J-C, et al. Perpendicular magnetization reversal in Pt/[Co/Ni]3/Al multilayers via the spin Hall effect of Pt. Appl Phys Lett. 2016;108:082406. doi: 10.1063/1.4942672. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryu KS, Thomas L, Yang SH, Parkin S. Chiral spin torque at magnetic domain walls. Nat Nanotechnol. 2013;8:527–533. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torrejon J, et al. Interface control of the magnetic chirality in CoFeB/MgO heterostructures with heavy-metal underlayers. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4655. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng Y, et al. Enhancement of spin-orbit torques in Ta/Co20Fe60B20/MgO structures induced by annealing. AIP Advances. 2017;7:075305. doi: 10.1063/1.4993765. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thiaville A, Rohart S, Jue E, Cros V, Fert A. Dynamics of Dzyaloshinskii domain walls in ultrathin magnetic films. Europhys Lett. 2012;100:57002. doi: 10.1209/0295-5075/100/57002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emori S, et al. Spin Hall torque magnetometry of Dzyaloshinskii domain walls. Phys Rev B. 2014;90:184427. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.90.184427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hrabec AN, et al. Measuring and tailoring the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction in perpendicularly magnetized thin films. Phys Rev B. 2014;90:020402. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.90.020402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Wei D, Gao K-Z, Cao J, Wei F. The role of inhomogeneity of perpendicular anisotropy in magnetic properties of ultra thin CoFeB film. J Appl Phys. 2014;115:053901. doi: 10.1063/1.4863139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sethi P, Murapaka C, Lim GJ, Lew WS. In-plane current induced domain wall nucleation and its stochasticity in perpendicular magnetic anisotropy Hall cross structures. Appl Phys Lett. 2015;107:192401. doi: 10.1063/1.4935347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rohart S, Thiaville A. Skyrmion confinement in ultrathin film nanostructures in the presence of Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Phys Rev B. 2013;88:184422. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.88.184422. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jang SY, You CY, Lim SH, Lee SR. Annealing effects on the magnetic dead layer and saturation magnetization in unit structures relevant to a synthetic ferrimagnetic free structure. J Appl Phys. 2011;109:013901. doi: 10.1063/1.3527968. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.