Abstract

Purpose

Despite improvement in vaccines against human papilloma virus (HPV), the causative agent of cervical cancer, screening women for cervical precancer will remain indispensable in the coming 30–40 years. A simple test that could be performed at home or at a doctor’s practice and that informs the woman whether she is at risk would significantly help make a broader group of patients who aware that they need medical treatment. Cervical vaginal fluid (CVF) is a body fluid that is very well suited for such a test.

Methods

Narrative review of cervical (pre)cancer candidate biomarkers from cervicovaginal fluid, is based on a detailed review of the literature. We will also discuss the possibilities that these biomarkers create for the development of a self-test or point-of-care test for cervical (pre)cancer.

Results

Several DNA, DNA methylation, miRNA, and protein biomarkers were identified in the cervical vaginal fluid; however, not all of these biomarkers are suited for development of a simple diagnostic assay.

Conclusions

Proteins, especially alpha-actinin-4, are most suited for development of a simple assay for cervical (pre)cancer. Accuracy of the test could further be improved by combination of several proteins or by combination with a new type of biomarker, e.g., originating from the cervicovaginal microbiome or metabolome.

Keywords: Biomarker, Cervical vaginal fluid, Cervical cancer

Cervical cancer and the need for a bedside assay

Current diagnosis of cervical cancer: the need for triage

Considering cervical cancer is the fourth most common female cancer worldwide, it remains a significant global problem [1], indicating that better screening and adequate interventions are necessary to reduce mortality. On the other hand, HPV vaccines offer the potential to significantly reduce the incidence of infection with an oncogenic high-risk (hr) HPV type, the causative agent for cervical cancer. Currently, two HPV vaccines are commercially available, Cervarix (GlaxoSmithKline) and Gardasil (Merck & Co). Cervarix is (cross)reactive against HPV types-16, -18, -31, -33, -45, -51 and -56, which are the seven most common cancer-causing types [2]. Gardasil is effective against HPV-16, 18 and 31, and this vaccine is also effective against HPV-6 and -11, which cause genital warts and respiratory papillomatosis [2]. A nonavalent vaccine (Gardasil 9) was recently approved that protects against nine different types of HPV (types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58) [3–5].

However, despite the advancements in HPV vaccination, these vaccines do not cover all hr-HPV types [6] and are less efficient in women who were previously infected with HPV [7]. Together with the lack of HPV vaccination programs in many low-resource countries, these observations indicate the lasting need for population-wide cervical cancer screening programs, which further requires accurate diagnosis of the disease. Moreover, cautiously monitoring [8] vaccination programs also demands accurate detection methods.

The gradual development of cervical cancer (years) with the occurrence of several precancerous stages and the relative ease with which the tumor can be accessed offer the opportunity to screen population-wide for cervical cancer during prevention campaigns. Cervical cancer screening programs are generally based on the detection of hr-HPV via DNA or RNA assays or on the detection of cytological and/or molecular changes in cervical cells via (immuno)staining methods, such as the Papanicolaou (Pap) smear [8].

High-risk HPV DNA-based PCR tests are currently of high interest because they are 40% more sensitive at detecting a cervical abnormality than cytology [9, 10]. However, despite their higher sensitivity, these assays cannot distinguish between clinically relevant HPV infections. Indeed, approximately 80% of hr-HPV infected women spontaneously clear the virus within 1 year after acquisition [11], resulting in significant overtreatment of hr-HPV-infected women.

Cytology-based screening has several other limitations, such as the high intra- and interobserver variability, limited sensitivity, high costs and limited screening coverage [12–14]. Currently, cytology/HR-HPV DNA co-testing remains the best strategy for detecting high-grade cervical vaginal lesions [15]. In the case of positive test results, the patient is usually referred to the clinic for a colposcopy examination that detects changes in the glycogen metabolism in cervical (pre)cancerous cells [16].

The conclusion is that because of the limitations of each of these methods, screening programs are never 100% safe (false negatives). Moreover, they are subject to oversampling (high number of false positives), leading to the treatment of women with clinically irrelevant hr-HPV infections, which increases the costs and possible harm caused by the treatment. Additional triage tests, on a molecular basis, are thus necessary to provide an objective and reproducible basis for the selection of patients with clinically significant disease. Today, the best alternative is dual staining for p16INK4a/Ki-67 [17–19], but this method may have an increased cost and previous work has demonstrated that p16 may not have sufficient discriminatory power because normal cells also express p16 (albeit at lower levels) [20]. Therefore, alternative methods, such as the combination stainings of TOP2A and Ki-67 [21] or p16INK4a/Ki-67 and L1 capsid protein [22], are being sought. Unfortunately, biomarkers with good predictive values (e.g., predicting progress towards cervical carcinoma while appearing at the CIN2 stage, which still allows for treatment) do not exist yet (reviewed by [23–25]). Moreover, it is expected that a panel of biomarkers will be necessary for an accurate test that distinguishes between the several CIN states with good clinical sensitivity and specificity. Preferentially, such combined biomarkers are unrelated, e.g., molecules from different cervical cancer pathways, cancer- vs. immune-related molecules, proteins vs. (methylated) nucleic acids, such that the assay is based on a broad series of independent recognition points.

CVF as a candidate body fluid for cervical cancer screening by self-testing

Self-sampling

In 2014, Arbyn et al. [26] showed that hr-HPV DNA testing on a self-sample is a way to include women who normally do not participate in regular cytology screening programs. Indeed, self-sampling has proven effective in increasing participation and screening coverage of the target population [27–32]. Many studies performed in different ethnic populations have demonstrated that self-sampling of cervical tissue via brushes, tampons, swabs or lavages is a good sample collection method for subsequent DNA genotyping, cytology or immunohistochemistry [26, 33–38]. The sampled tissue is usually resuspended in liquid buffer [39–42], although dry storage is also considered, e.g., by capping the brush [43] or by swiping the sample on paper that was chemically treated with reagents to lyse cells upon application so that they are non-infectious for safe and easy transport [44–47]. The samples are then sent to the laboratory for further analysis.

Using the emerging proteomics technologies that have become increasingly sensitive, our group and others groups have conducted several studies on the identification of the cervical vaginal proteome [48–65]. Functional classification of the CVF proteome demonstrates a significant diversity of biological roles, of which “protein metabolism and modification” and “immunity and defense” are the largest GO categories (17 and 10%, respectively). Moreover, classification based on cellular localization shows that most proteins are present in the cytoplasm or in the extracellular region (21 and 20%, respectively) [57].

Because of the immediate contact of the precancerous or cancerous tissue with the CVF, we expect that the concentrations of important cervical cancer biomarkers will be high in CVF. Unlike plasma, CVF does not contact many other tissues, and its volume is limited (milliliters versus liters). Moreover, the liquid can easily be collected by self-sampling in a non-invasive way using devices for lavages [36, 66], or using tampons [38, 67] (self-sampling devices developed before 2014 were reviewed in Othman et al. [68]). Therefore, self-sampling of CVF could overcome the practical (e.g., busy schedule, transport, and distance), emotional (e.g., fear of pain and embarrassment), and cognitive (e.g., low perceived risk and absence of symptoms) barriers that some women experience in attending cervical cancer screening programs [69–71]. Ideally, the same, self-collected sample should be used for the detection of several biomarkers, demanding minimal effort from women.

Self-testing

Especially in low-resource countries and remote rural areas where mail and transport are much less frequent, the continuous running of an efficient screening program for cervical cancer may demand organizational, financial and logistical efforts [72, 73] that may not always be available. A simple test, such as a lateral flow assay (LFA) that could be performed by the woman herself could be a solution to this problem because it does not require specialized instruments or personnel, and it could be performed at home or e.g., at a doctor's practice (point-of-care). LFA assays are frequently used to detect a variety of clinical analytes in plasma, serum, urine, cells, tissues and other biological samples and are also used for veterinary and industrial purposes [74–76]. Although efforts have been made to develop LFA tests for detecting HPV DNA from precancerous tissue [77], detection of proteins would be most suitable. Indeed, because of the frequent spontaneous elimination of the lesion, the presence of HPV virus does not always correspond with the presence of (pre)cancerous tissue. On the other hand, detection of proteins from precancerous cervical tissue in the cervical vaginal fluid would directly indicate the presence of such tissue. If such biomarkers could distinguish between the three CIN stages, a manual could inform the patient about whether to see a doctor. To avoid inclusion of a cell lysis step, which would compromise ease of handling, detection of secreted and/or released proteins from the precancerous lesions into the CVF is recommended for LFA.

A typical example of an LFA test that is already on the marked, is the self-test for HIV (HIVST). According to the WHO such a test used and interpreted by a self-tester can perform as well as an HIV RDT used and interpreted by a trained health worker [78] although concerns remain about test sensitivity (particularly in early infection), and linkages to care for confirmatory testing after a reactive HIVST [79]. Nevertheless, HIVST is likely to become more widely available, including in low- and medium-income countries, as it is generally accepted among key populations [80] and, therefore, has the potential to drastically increase HIV testing coverage. It is, therefore, quite possible that the HIVST LFA assay is a trendsetter in human self-diagnostic medicine.

In summary, we believe that CVF is a rich source of information regarding the physiological status of the female genital organs, including the healthy or cancerous state of the cervical region. Components from the CVF could, therefore, be used as the basis for a simple self-test/point-of-care test that, when sufficiently accurate, may overcome current problems with coverage and specificity.

CVF biomarkers for cervical cancer

HPV DNA assay

Many studies report on the efficiency of HPV DNA testing from self-collected cervical tissue samples, compared to samples collected by a practitioner. In most studies, HPV testing on self- and clinician-sampled specimens is similarly accurate with respect to CIN2+ detection as reported in a large cohort study [42, 81] or a meta-analysis [33], although this may depend on the test used [26].

As for detection of HPV DNA from cervical vaginal fluid there was a high agreement between the (self-sampled) CVF and the reference smears (between 89 and 93%, depending on the test used) [82] and no difference in viral load was observed when samples were collected in the estrogen-dominated proliferative phase or the progesterone-dominated secretory phase [83].

Unfortunately, HPV DNA detection requires very specialized equipment (in the previous study, a Roche cobas 4800 system); therefore, it is not suited for a self-test. Furthermore, as mentioned above, the test cannot distinguish between productive and progressive infections, resulting in a low specificity.

Host and viral DNA methylation

With the discovery that global DNA hypomethylation progressively increases in cervical dysplasia and carcinoma [84], Widschwendter et al. [85] investigated DNA methylation in cervical vaginal specimens collected on a tampon of 11 host genes known to be methylated in cervical cancer (SOCS1, CDH1, TIMP3, GSTP1, DAPK, hTERT, CDH13, HSPA2, MLH1, RASSF1A, and SOCS2) and reported a correlation of the methylation status with the severity of the cervical lesion, such that invasive cervical cancers could be predicted. Along the same line, Sun and coworkers [86] analyzed in cervical vaginal lavages methylation at 14 CpG sites within the HPV16 L1 region and noticed a significant increase in methylation in samples from women with CIN3+ compared to the HPV16 genomes from women without CIN3+, indicating that hyper/hypomethylation of viral CpG sites may constitute a potential biomarker for precancerous and cancerous cervix disease [86]. In a high-throughput experiment using the Illumina 450 k DNA methylation array, Doufekis et al. [87] investigated the DNA methylation in vaginal fluid samples at more than 480,000 CpG sites and found a DNA methylation signature for cervical and endometrial cancer which resulted in a ROC area under the curve between 0.75 and 0.83.

DNA methylation of miRNA

MicroRNAs have not only been detected in the serum or plasma of patients who are precancerous for cervical cancer (cervical adenocarcinoma and squamous cell cancer) [88], they have also been detected in CVF. In a large, randomized study of self-sampled cervical vaginal fluid, Verhoef et al. [89, 90] investigated direct DNA methylation of miR-124-2 and MAL genes on samples that tested positive for HPV and showed that DNA methylation analysis is non-inferior to cytology triage in the detection of CIN2 or higher. 2 years later, the combination of miR-124-2 methylation and methylation of another gene, FAM19A4, was investigated in a large cohort of HPV positive women by the same group [91]. The accuracy of the assay was similar for CVF self-collected samples and for clinician-collected cervical smears.

Exosomes

Interestingly, after silencing HPV E6/E7 oncogene expression in HPV-positive cervical cells, such as HeLa cells, a distinct seven-miRNA-signature was identified in the exosomes secreted by the HeLa cells, which was accompanied by significant downregulation of let-7d-5p, miR-20a-5p, miR-378a-3p, miR-423-3p, miR-7-5p, miR-92a-3p and upregulation of miR-21-5p [92]. Later, similar results were obtained in keratinocytes transduced with E6 and E7 from mucosal HPV-16 or cutaneous HPV-38 [93]. This raised the idea of using CVF-derived exosomes for diagnostic purposes. Indeed, Liu et al. [94] described microRNA-21 and microRNA-146a to be upregulated in cervical cancer patients in association with the high levels of cervical cancer-derived exosomes in CVF, and Zhang et al. [95] recently showed that expression of the HOTAIR, MALAT1 and MEG3 long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) was predominantly observed in cervical cancer-derived exosomes in cervical vaginal lavage samples.

Hence, it is clear that DNA methylation or RNAs could serve as a CVF biomarker for intraepithelial cancerous lesions; however, analogous to DNA PCR, a methylation-specific or RNA-specific PCR reaction requires skilled people and specialized instruments, making it unsuitable for self-testing.

First discovered protein markers

The discovery that carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), CA19-9 and CA125 were present in the CVF of patients with cervical cancer or with a cervical precancerous lesion led to optimism in the 80 s that these biomarkers could help in detecting cervical cancer or its precancerous stages [96–99]. Later, it was found that these antigens were normal constituents of vaginal fluid and that their distribution was not only affected by cancer of the genital tract but also by pregnancy [100, 101] and inflammation [102], limiting their applicability for use as biomarkers. Nevertheless, the presence of CA125 in the CVF has also been correlated with endometrial cancer [103].

Immunological proteins

In a later study [104, 105], in 60% of the patients with HPV 16 positive cervical cancer, anti-HPV 16 E7 specific IgG antibodies were found in cervicovaginal washings and sera, while no IgG reactivity was found in healthy individuals. Moreover, IgG antibody reactivity in cervicovaginal washings was higher than in the paired serum samples. Nevertheless, because the presence of these antibodies was less clear in premalignant tissue and since they could only be detected in 60% of the patients, the sensitivity and specificity are not sufficient for biomarker purposes. The same group analyzed the presence of various cytokines in cervicovaginal washings of healthy volunteers, CIN patients and cervical cancer patients and demonstrated alterations in the local cervical immune environment in cervical cancer patients. Indeed, the IL-12p40, IL-10, TGF-beta1, TNF-alpha and IL-1beta levels were significantly higher in patients with cervical cancer than in controls and CIN patients [106, 107]. Although these results are of interest for the development of immune modulating therapies and vaccination strategies, they cannot be used for diagnostic applications because no differences were seen between CIN patients, and the cytokine levels may vary according to other infections.

Since then, many studies were undertaken to identify cervical (pre)cancer protein biomarkers from swab samples or biopsies [23–25, 108, 109], yet no other cervical cancer biomarker proteins were found in the CVF.

Alpha-actinin-4

Discovery

In a differential proteomics study on CVF samples from six healthy and six precancerous (CIN I, II and III) women, we identified 16 candidate biomarkers ([63], Table 1). From these, alpha-actinin-4 (ACTN4) was absent and present in all samples from healthy and precancerous women (p = 0.001), respectively. ELISA on 28 additional samples showed a discriminatory potential of ACTN4 at 18 pg/ml protein extract between samples from healthy and both low-risk and high-risk HPV-infected women (p = 0.009). Analyzing the ACTN4 concentration in 26 CVF samples originating from longitudinal studies on 9 women who experienced an HPV infection, who had a persistent infection or who cleared the virus showed that the ACTN4 levels correlated with increasing, persisting or decreasing presence of HPV E6 DNA [63].

Table 1.

Samples used for calculating the ACTN4 discriminatory power as a biomarker for cervical (pre)cancer

| Cohort | Sample | Group | Condition | Genotype | Viral load (copies/cell) | Colposcopy | Cytology | Collection medium | ACTN4 (/mg prot) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van Raemdonck et al. [63, 64] | H07 | Healthy | HPV neg | Normal | Normal | 5% AA | 42.8 | ||

| H12 | Healthy | HPV neg | Normal | Normal | 5% AA | 0.6 | |||

| H52 | Healthy | HPV neg | Normal | Normal | 5% AA | 6.1 | |||

| H54 | Healthy | HPV neg | Normal | Normal | 5% AA | 1.9 | |||

| H62 | Healthy | HPV neg | Normal | Normal | 5% AA | 7.2 | |||

| H20 | Healthy | HPV neg | Normal | Normal | 5% AA | 0.5 | |||

| H05 | Healthy | HPV neg | Normal | Normal | 5% AA | 3.1 | |||

| H64 | Healthy | HPV neg | Normal | Normal | 5% AA | 3.6 | |||

| H28 | Healthy | HPV neg | Normal | Normal | 5% AA | 0.0 | |||

| H69 | Healthy | HPV neg | Normal | Normal | 5% AA | 5.3 | |||

| H70 | Healthy | HPV neg | Normal | Normal | 5% AA | 0.1 | |||

| H08 | Healthy | HPV neg | Normal | Normal | 5% AA | 8.7 | |||

| H14 | Healthy | HPV neg | Normal | Normal | 5% AA | 7.5 | |||

| H73 | Healthy | HPV neg | Normal | Normal | 5% AA | 3.5 | |||

| H87 | Healthy | HPV neg | Normal | Normal | 5% AA | 0.0 | |||

| H90 | Healthy | HPV neg | Normal | Normal | 5% AA | 8.2 | |||

| H09 | Low risk | 6 | 96,249 | ASCUS | Normal | 5% AA | 12.7 | ||

| H35 | Low risk | 11 | 51,740 | ASCUS | CIN1 | 5% AA | 10.7 | ||

| H182 | Low risk | 6 | 1.00 | Normal | Normal | 5% AA | 20.7 | ||

| H213 | Low risk | 6 | 0.05 | Normal | Normal | 5% AA | 29.9 | ||

| P24 | High risk | 16/39 | 7729/1661 | ASCUS | CIN3 | 5% AA | 17.1 | ||

| P27 | High risk | 52 | 129 | LSIL | CIN1 | 5% AA | 113.9 | ||

| P60 | High risk | 16/31/52/66 | 0.02/11/12/31 | LSIL | CIN1 | 5% AA | 32.6 | ||

| P61 | High risk | 16/31/39/52/66 | 288/0.20/4/7416/179 | LSIL | CIN1 | 5% AA | 22.2 | ||

| P41 | High risk | 16/58 | 11571/253 | HSIL | CIN2 | 5% AA | 45.0 | ||

| P36 | High risk | 16/53/58/59 | 9126/79/2733/1510 | LSIL | CIN1 | 5% AA | 70.4 | ||

| P70 | High risk | 35 | 5159 | LSIL | CIN2 | 5% AA | 15.3 | ||

| P40 | High risk | 31 | 1696 | HSIL | CIN1 | 5% AA | 15.5 | ||

| Additional samples (cohort Van Raemdonck et al. [63]) | 205 | Healthy | HPV neg | Normal | 5% AA | 0.0 | |||

| 207 | Healthy | HPV neg | Normal | 5% AA | 0.0 | ||||

| 211 | Healthy | HPV neg | Normal | 5% AA | 0.0 | ||||

| 212 | Healthy | HPV neg | Normal | 5% AA | 0.0 | ||||

| 229 | Healthy | HPV neg | Normal | 5% AA | 36.1 | ||||

| 206 | High risk | HPV neg | ASCUS | 5% AA | 154.5 | ||||

| 204 | High risk | 45 | LSIL/HSIL | 5% AA | 0.0 | ||||

| 210 | High risk | 16 | LSIL | 5% AA | 52.1 | ||||

| 224 | High risk | 18/39/56 | LSIL | 5% AA | 0.0 | ||||

| 225 | High risk | 56 | LSIL | 5% AA | 0.0 | ||||

| Van Raemdonck et al. [63, 64] (longitudinal samples) | 42 | Patient L1 | High risk new infection | 52/53/59/66 | 178/0.07/50/6 | LSIL | 5% AA | 0.5 | |

| 119 | 52 | 26.00 | Normal | 5% AA | 5.0 | ||||

| 308 | 16/52 | 171/283 | ASCUS | 5% AA | 22.7 | ||||

| 85 | Patient L2 | High risk clearing | 33/52/58/66 | 0.01/9147/268/526 | LSIL | 5% AA | 32.1 | ||

| 146 | HPV neg | 0.00 | LSIL | 5% AA | 11.2 | ||||

| 281 | HPV neg | 0.00 | Normal | 5% AA | 0.5 | ||||

| 36 | Patient L4 | High risk persisting | 16/53/58/59 | 9126/79/2733/1510 | LSIL | 5% AA | 17.7 | ||

| 105 | 16/53/58 | 99,999/11/4123 | LSIL | 5% AA | 37.1 | ||||

| 172 | 16/58 | 3/99,999 | LSIL | 5% AA | 39.7 | ||||

| 290 | 58 | 4997.00 | LSIL | 5% AA | 46.0 | ||||

| 154 | Patient L5 | Healthy | HPV neg | 0.00 | Normal | 5% AA | 4.2 | ||

| 242 | 31 | 0.62 | Normal | 5% AA | 0.5 | ||||

| 302 | HPV neg | 0.00 | Normal | 5% AA | 2.0 | ||||

| 15 | Patient L6 | High risk clearing | 16/39/53 | 2627/12,052/0.51 | LSIL | 5% AA | 10.1 | ||

| 135 | 16 | 4.00 | Normal | 5% AA | 0.5 | ||||

| 271 | 16 | 33.00 | Normal | 5% AA | 1.8 | ||||

| S266 | Patient L7 | High risk clearing | 16/31/51/56 | 111/0.2452/33/271 | LSIL | 5% AA | 15.0 | ||

| 23 | HPV neg | 0.00 | Normal | 5% AA | 0.5 | ||||

| 127 | HPV neg | 0.00 | Normal | 5% AA | 3.1 | ||||

| 359 | HPV neg | 0.00 | Normal | 5% AA | 1.3 | ||||

| 43 | Patient L8 | High risk new infection | HPV neg | 0.00 | Normal | 5% AA | 0.5 | ||

| 147 | 51/59 | 99,999/46 | LSIL | 5% AA | 17.4 | ||||

| 348 | 51/59 | 0.13/165 | ASCUS | 5% AA | 7.2 | ||||

| 70 | Patient L9 | High risk clearing | 35 | 5159.00 | HSIL | 5% AA | 6.3 | ||

| 177 | HPV neg | 0.00 | Normal | 5% AA | 0.6 | ||||

| 342 | HPV neg | 0.00 | Normal | 5% AA | 0.5 | ||||

| 103 | Patient L10 | High risk persisting | 31 | 351.00 | Normal | 5% AA | 18.1 | ||

| 218 | 31 | 1556.00 | Normal | 5% AA | 25.0 | ||||

| 343 | 31 | 3479.00 | ASCUS | 5% AA | 60.8 | ||||

| Berlin cohort | DS77 | High risk | 16/31/52 | CIN3 | PBS | 0.0 | |||

| DS78 | High risk | 16 | CIN3 | PBS | 896.2 | ||||

| DS72 | Cancerous | 16 | CxCa | PBS | 782.9 | ||||

| DS73 | Cancerous | HPV neg | CxCa after conisation | PBS | 719.0 | ||||

| DS80 | Cancerous | 18/56 | Cx AdenoCa | PBS | 355.2 | ||||

| DS86 | Cancerous | 16 | CxCa | PBS | 463.8 | ||||

| DS90 | Cancerous | HPV neg | CxCa FIGO IIIb N1 (1/10) | PBS | 559.0 | ||||

| DS74 | Cancerous | 16 | CxCa 1a1 VAIN III | PBS | 2316.7 | ||||

| DS79 | Cancerous | 16 | ZxCa susp. Peritoneal | PBS | 3075.2 | ||||

| DS84 | Cancerous | HPV neg | CxCa | PBS | 500.0 | ||||

| DS87 | Cancerous | HPV neg | CxCa pT1a2 G2 L1 V0 R1 | PBS | 178.1 | ||||

| DS88 | Cancerous | 16 | CxCa FIGO IIa | PBS | 949.2 | ||||

| DS89 | Cancerous | 16 | CxCa FIGO IIb | PBS | 1354.8 | ||||

| DS91 | Cancerous | 18/43 | CxCa FIGO lib | PBS | 636.4 | ||||

| Van Raemdonck et al. [64] | 5714 | No HIV | ESN population | HPV neg | – | – | PBS | 2.5 | |

| 3896 | No HIV | ESN population | HPV neg | – | – | PBS | 4.2 | ||

| 6624 | HIV | ESN population | HPV neg | – | – | PBS | 0.0 | ||

| 6589 | HIV | ESN population | HPV neg | – | – | PBS | 0.0 | ||

| 6488 | HIV | ESN population | HPV neg | – | – | PBS | 0.0 |

Three different cohorts were included with a varying CVF sample size and collection medium. A series of samples from the first cohort consisted of 28 singular samples and samples taken at different time points from 9 patients (longitudinal samples) [63]. These were further supplemented with ten additional singular samples from the same cohort. Fourteen samples were from another cohort (Charité, Berlin; Charite IRB Ethics Approval EA02/129/08), consisting of samples from two women with CIN III and twelve women with different stages of cervical cancer. We also included five CVF samples from a previously described cohort [64]. From this cohort, all samples were HPV-negative, as demonstrated by RT-PCR genotyping [161], and three of them came from HIV-positive women. Classification was made based on colposcopy examination and/or cytology results. In case both examinations gave conflicting results, colposcopy results had priority. Samples from healthy individuals were given a gray background. Since the study by Van Raemdonck et al. [64] lacked colposcopy and cytology, the absence of (pre)cancerous tissue was decided on the basis of HPV absence

Alpha-actinin-4 and cancer

Alpha-actinin-4 is predominantly expressed in cellular filopodia and lamellipodia, and as such, it is important for the formation of cell protrusions and migration [110]. Experiments in colon and pancreatic cancer cells have shown that ACTN4 overexpressing cells are highly mobile and have a significantly increased metastatic ability [111–114]. Apart from in colorectal and pancreatic cancer, the protein is also overexpressed in ovarian cancer, osteosarcoma, lung cancer, oral squamous cell carcinoma, salivary gland carcinoma, bladder cancer, breast cancer and esophageal cancer (for an overview, see [115]). ACTN4 gene amplifications were shown to correlate with pancreatic cancer [113] and could be a potential biomarker for metastatic potency and for predicting the effectiveness of chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced pancreatic cancer [116]. Elevated levels of ACTN4 contribute to the increased migratory potential of neuroblastomas [117]. Worsened survival rates were seen in ACTN4 overexpressing ovarian tumors [118]. Moreover, studies have demonstrated that in addition to its role in cytoskeleton remodeling, ACTN4 interacts with signaling mediators, chromatin remodeling and transcription factors. Nuclear localization of the protein was seen in different tumors [110, 119, 120], and recruitment of ACTN4 to the pS2 promotor, an estrogen receptor (ER) target in the ER-positive breast cancer cell line MCF7, suggested that ACTN4 may play a role in E2-mediated regulation of breast cancer proliferation [121, 122]. Interestingly, ACTN4 has been reported to be present in exosomes from tumor (mesothelioma) cells [123]. ACTN4 thus functions as a promoter for many tumor types and could be an important target protein in drug development. Therefore, it is not surprising to see the protein appearing in the cervical vaginal fluid of women who have cervical precancerous lesions. ACTN4 may, therefore, play an important role in the development of a simple bedside assay for cervical cancer based on CVF components.

Efficiency of alpha-actinin-4 as a CVF biomarker for cervical cancer

For a preliminary determination of the sensitivity and specificity of ACTN4 as a cervical (pre)cancer biomarker, we extended our sample pool with 10 CVF samples from the previous cohort [63], 14 CIN III or cervical cancer samples from a Berlin cohort (see Table 1) and five samples from an African cohort, three of which were from women infected with HIV-1 [64] (Table 1). Based on colposcopic determination of the precancerous state, we divided the samples into two classes. The first class (N = 43) contained samples originating from healthy women, while the second class (N = 43) contained samples originating from women with small (ASCUS, LSIL) or larger (HSIL) signs of precancerous tissue or with cancerous tissue. Because the samples came from different hospitals in different volumes, we took the total mass of protein as a reference instead of the sample volume. For this normalization, the ACTN4 concentration was recalculated as pg/mg total protein instead of pg/ml. The resulting ROC curve showed an AUC of 86% (Fig. 1) with a sensitivity (true positives/true positives + false negatives) and specificity (true negatives/true negatives + false positives) of 84 and 86%, respectively, when a cutoff value of 10 pg ACTN4/mg total protein was used. It must be mentioned that this value was obtained despite differences in the volumes and collection media resulting from the inclusion of different cohorts. Because only a limited number of samples from women with precancerous tissue above CIN II or CIN III were included in this study (N = 6), it was not possible to correlate the ACTN4 concentration with different CIN stages. However, clear overexpression of ACTN4 was visible in all cancerous samples. Interestingly, none of the three samples from HIV-1 infected (HPV negative) individuals scored above the cutoff value, suggesting that HIV-1 infection does not interfere with the ACTN4 levels in CVF. Studies in our lab are currently ongoing to examine the correlation of the ACTN4 concentration with the CIN stages and to evaluate the CVF concentration in women infected with additional sexually transmitted viruses, bacteria and protozoa.

Fig. 1.

ACTN4 ROC curve for discrimination between the healthy and anomalous (ASCUS, CIN I and higher) state. Data from Table 1 were used. Numbers of samples for healthy and anomalous state were 48 and 43, respectively. The ROC curve was created by SPSS with inclusion of cutoff values for positive classification. Sensitivity and specificity values were, respectively, 84 and 86% when a cutoff value of 10 pg ACTN4/mg total protein was used, resulting in an area under the curve (AUC) of 86%

Network biomarkers

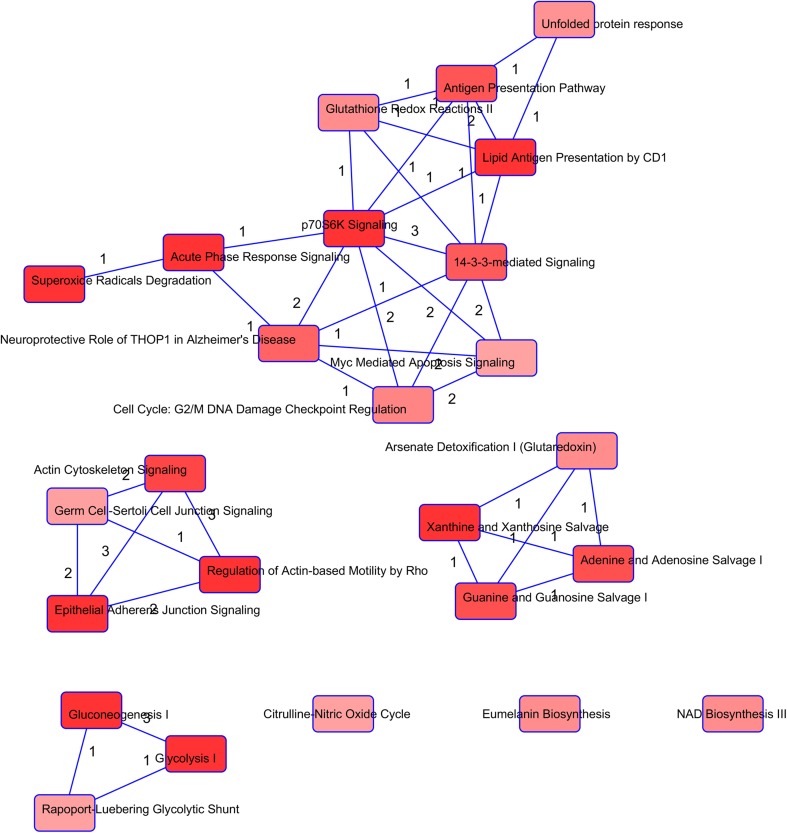

Assuming that precancerous tissue is (partially) attacked by the immune system, we hypothesized that ACTN4 is released in the CVF from lysed epithelial cells with many other intracellular factors, including those involved in the development of precancerous lesions and/or cervical cancer. Aberrant concentrations of (some of) these factors in the CVF may indicate there is growing precancerous tissue and, therefore, an increased chance of developing a malignant tumor. Therefore, starting from the protein lists we obtained from the differential proteomics study on CVF from healthy and precancerous patients [63], protein IDs (Table 2) were introduced into the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) program, and common pathways were searched [124]. Interestingly, proteins in CVF from precancerous women interconnected much more inside pathways that make up the ‘hallmarks of cancer’ described by Hanahan and Weinberg [125–127] compared to CVF proteins from healthy people. In addition, a literature search showed that CVF proteins classified by IPA in the ‘cancer’ category were more correlated with cervical cancer when they originated from the CVF of precancerous women. Moreover, many of these proteins clustered in a network with angiotensin II as a central mediator [124], and further IPA studies showed their overrepresentation in the following four clusters of pathways that belong to a cancer hallmark: (1) gluconeogenesis/glycolysis, (2) adenine/guanine metabolism, (3) adherens/tight junction formation and 4) a larger set of interconnected pathways clustered around the p70S6K pathway (Fig. 2). The first two clusters are a result of increased metabolism, a typical feature of tumor cells. Interestingly, the p70S6K pathway has been described to be involved in cell motility [128]; hence, the two last pathway clusters influence the migration of cells and concomitant metastatic activity. Indeed, an altered expression of tight and adherens junction proteins was frequently reported in cervical neoplasia [129–131], and Claudin-1, a component of tight junction strands, was recently described as having similar diagnostic potential as p16INK4a in histological and cytological biomarker assays for cervical cancer detection [132]. Additionally, the association of ACTN4 with adherens junction formation has been described [110, 133]. Such ‘network biomarkers’, rather than single biomarkers, could increase the accuracy and prognostic value of cervical cancer diagnosis and allow us to better identify the early presence of the tumor, tumor type, and development state.

Table 2.

Proteins that differ in CVF abundance between healthy individuals and individuals with cervical precancerous tissue (CIN I or higher)

| Name | Acc. No | ID |

|---|---|---|

| Increased levels in CVF from women with adenocarcinoma: | ||

| Fujii et al. [98], Harlozinska et al. [97] and McDicken et al. [96] | ||

| Carcino embryonic antigen (CEA) | Q13984 | Q13984_HUMAN |

| carbohydrate antigen disialyl Lewis a, CA19-9 | Q969X2 | SIA7F_HUMAN |

| Increased levels in CVF from women with precancerous lesions with stringent selection (p < 0.05) | ||

| Van Raemdonck et al. [63] | ||

| 14-3-3 protein epsilon | P62258 | 1433E_HUMAN |

| Actin-related protein 3 | P61158 | ARP3_HUMAN |

| Alpha-actinin-4 | O43707 | ACTN4_HUMAN |

| Annexin A2 | P07355 | ANXA2_HUMAN |

| ATP synthase subunit beta, mitochondrial | P06576 | ATPB_HUMAN |

| Cellular retinoic acid-binding protein 2 | P29373 | RABP2_HUMAN |

| Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase | P43490 | NAMPT_HUMAN |

| Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | P00558 | PGK1_HUMAN |

| Putative elongation factor 1-alpha-like 3 | Q5VTE0 | EF1A3_HUMAN |

| Pyruvate kinase isozymes M1/M2 | P14618 | KPYM_HUMAN |

| Serpin B13 | Q9UIV8 | SPB13_HUMAN |

| Squamous cell carcinoma antigen 1 (SCCA-1); Serpin B3 | P29508 | SPB3_HUMAN |

| Exclusive occurrence in CVF from women with precancerous lesions and described to be involved in cervical cancer | ||

| Van Raemdonck et al. [63] and Van Ostade et al. [125] | ||

| 14-3-3 protein theta | P27348 | 1433T_HUMAN |

| Angiotensinogen | P01019 | ANGT_HUMAN |

| Annexin A4 | P09525 | ANXA4_HUMAN |

| Cathepsin B | P07858 | CATB_HUMAN |

| CD59 glycoprotein | P13987 | CD59_HUMAN |

| Ceruloplasmin | P00450 | CERU_HUMAN |

| Gelsolin | P06396 | GELS_HUMAN |

| High mobility group protein B2 | P26583 | HMGB2_HUMAN |

| Interleukin-18 | Q14116 | IL18_HUMAN |

| Macrophage migration inhibitory factor | P14174 | MIF_HUMAN |

| Macrophage-capping protein | P40121 | CAPG_HUMAN |

| Mucin-5B | Q9HC84 | MUC5B_HUMAN |

| Myosin light polypeptide 6 | P60660 | MYL6_HUMAN |

| Phosphoglycerate mutase 1 | P18669 | PGAM1_HUMAN |

| Protein disulfide isomerase A3 | P30101 | PDIA3_HUMAN |

| Protein S100-P | P25815 | S100P_HUMAN |

| Serpin B13 | Q9UIV8 | SPB13_HUMAN |

| Superoxide dismutase [Mn] | P04179 | SODM_HUMAN |

From the list of proteins identified in Van Raemdonck et al. [63], the following two subsets were distinguished: (1) proteins that were, to a high extent (p < 0.05), qualitatively or quantitatively different in the samples from precancerous women compared to the samples from healthy women and (2) proteins that, to a lower extent, qualitatively differed from the samples in precancerous women (presence in at least one of the six ‘precancerous’ samples, while not present in the ‘healthy’ samples), which were described to be interconnected and to play a role in cervical cancer [124]

Fig. 2.

Overlap of canonical pathways containing proteins from Table 2 after IPA Core Analysis. The degree of grayness defines the p value, where deeper red stands for the lowest p values. All p values are < 0.05. The numbers accompanying edges represent common proteins within the 2 connected canonical pathways

Perspectives

Microbiome

Over recent decades, a substantial amount of work has been done on the characterization of the vaginal microbiome in relation to several diseases. Two groups [134, 135] described the beneficial role of Lactobacillus species in vaginal and reproductive health, while overgrowth of G. vaginalis, A. vaginae, Eggerthella, Prevotella, BVAB2 and Megasphaera type 1 as well as a marked depletion of Lactobacillus were essential for the diagnosis of BV [136]. In a review by Datcu et al. [137], it was shown that subgroups of bacterial vaginosis (BV) could be identified wherein single or paired bacteria were dominant.

Several studies have also pointed to a correlation of microbiota with HPV and cervical (pre)cancer. Compared to HPV-negative women, the vaginal bacterial diversity of HPV-positive women is more complex [138], and because of an association between the cervical microbiota and CIN stages, the combined effect of the microbiota and HPV on the risk of CIN could be determined [139]. Moreover, Mitra et al. [140] showed an association of increasing CIN stage with increasing vaginal microbiota diversity, suggesting a role for microbiota in regulating viral persistence and disease progression. Such changes may be reflected in the expression levels of microbial enzymes, considering Dasari and coworkers [141] demonstrated that the microbial enzymes mucinase, sialidase, and protease were significantly (p < 0.01) elevated in patients with cervical dysplasia and, therefore, may serve as risk-factors for the development of cervical cancer.

Interestingly, shotgun microbiota sequencing also showed that the HPV community in healthy woman is much more complex than previously defined, suggesting that co-existing non-oncogenic HPV viruses may stimulate or inhibit the oncogenic virus via viral interference or immune cross-reaction [142].

Metabolome

Although not yet applied for diagnosing HPV or cervical (pre)cancerous lesions, metabolomics data were recently correlated with microbiome data in BV. Alterations in amino acid, carbohydrate, and lipid metabolism were associated with the presence and concentration of specific BV bacteria [143]. Additionally, a dramatic loss of lactic acid and higher concentrations of mixed short chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including acetate, propionate, butyrate, and succinate, characterized BV [144], and Nelson and coworkers [145] reported on the importance of biogenic amines for dysbiosis and the outgrowth of BV-associated vaginal bacteria. If assays can be developed for the simple and rapid quantification of such microbiome and metabolome alterations, their combination with classical ELISA-like protein/peptide tests may lead to a simple yet very powerful diagnostic tool for detecting cervical cancer and its several precancerous stages.

Urine

Since CVF is washed away with the first flow of urine, it is expected that especially first-void urine contains most of the CVF components, including the mucus and debris from vaginal and cervical exfoliated cells. This may explain why the first collected part of a urine void collected with a special device (Colli-Pee™, Novosanis, Belgium) contains more human and HPV DNA than the subsequent parts [146, 147]. Moreover, self-sampling of urine for subsequent HPV DNA tests was very well accepted by patients [148, 149] and provided sensitivity for CIN2+ detection comparable to a physician-taken smear or brush-based self-sample [150]. Several groups have attempted to identify urine components, other than HPV DNA, that could distinguish between healthy and precancerous states. The nature of these components varies from the hormone ratio [151] and collagen abundance [152] to host and/or viral gene methylation [153, 154]. However, although some of these studies show encouraging results, further validation is recommended with standardized protocols and higher patient numbers. Nevertheless, this does not exclude that biomarkers identified from experiments with CVF could be evaluated in urine and vice versa.

Alternative techniques

Although their complexity still prevents the development of self-tests or medical practice applications, several biophysical applications are currently being evaluated for high-throughput testing of CVF samples. Fourier transformed infrared spectroscopy (IR) was performed on 25 cervical vaginal lavage specimens from women referred for colposcopy [155]. For the CIN III stage, the authors showed a strong correlation between IR spectra and histopathology; however, less precise matching was seen for lower CIN grades. Therefore, it is possible that the differences seen in IR spectroscopy reflect the molecular abnormalities in cervical cells during progression to cancer. If so, the technique may help in clinical decision making, but more studies are required to make this a routine technique in cervical cancer screening.

Additionally, mass spectrometry could contribute to cervical cancer diagnosis. The technology could very well be used in specialized laboratories where samples are collected, and it could complement or replace current methods, such as cytology and immunohistochemistry. However, at present, the main limitation of MS techniques lies in the sensitivity. For instance, to detect alpha-actinin-4, we used a targeted LC–MS technique called multiple reaction monitoring (MRM), but so far we have been unsuccessful because the limit of detection of the LC-Triple Quadrupole system for ACTN4 in CVF was at least ten-fold higher than the cutoff value of 18 pg/ml. Whether CVF contains cervical cancer biomarker proteins that are sufficiently high in abundance for detection by mass spectrometry remains to be elucidated, but at least for CVF labor biomarkers, Brown and co-workers [156] showed that differences in proteome profiles were visible after protein separation on weak cation exchange chips and analysis using Surface-Enhanced Laser Desorption Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (SELDI-TOF–MS). Differences were attributed to fragments of alpha- or beta-hemoglobin. A fragment of alpha-hemoglobin was found to potentiate smooth muscle cell contraction in response to bradykinin, oxytocin and prostaglandin-F2alpha. Recently, Cricca et al. [157] compared a commercial kit for HPV genotyping with a Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Time Of Flight (MALDI-TOF) method, developed to genotype 16 high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) types in cervical cytology specimens, and concluded that the MALDI-based method is well-suited for broad spectrum HPV genotyping in large-scale epidemiological studies. A very elegant integration of cytology/histology methods and molecular tests could come from MALDI-imaging whereby the mass spectrum is recorded from a thin tissue section, allowing for localization of different analytes to become visible. In this way, the distribution of many proteins and their expression profiles in cytological samples were correlated with the histological features and Pap groups, allowing for unbiased and automated classification of cervical Pap smears [158].

Conclusion

In conclusion, several components residing in the cervical vaginal fluid are valuable candidate biomarkers for diagnostic tests for cervical cancer or its precancerous states. Since CVF and CVF-containing first-void urine are appropriate body fluids for use in self-tests or point-of-care tests, we could focus in the future on those biomarkers that lend itself to the development of such tests. Proteins are excellent candidates for this, and may originate from the virus, the tumor, the host immune system or the disturbed microbiome. For this, alpha-actinin-4 may offer a very good starting point, but we still have a way to go. Continued investigation is necessary to define a CVF/urine panel of biomarkers with which we can move forward to a standardized evaluation protocol such as in the PRoBE study design [159]. Moreover, when the biomarker(s) should be used for clinical decisions, impact on patient outcome must also be evaluated with great care [160].

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Luc Kestens (Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp) and Dr. Amrei Kings (Charité, Berlin) for providing us with CVF samples from the African and Berlin cohorts, respectively. We also thank Edmond Coen, Margot De Graeve, Lissa Van de Velde, Nick Valkenborg and Koen Snijders for performing some of the additional ELISA tests.

Author contributions

XVO: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing. MD: Data curation, Software, Writing. WT: Investigation, Resources, Writing, Providing samples. GVR: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

X. Van Ostade declares that he has no conflict of interest. M. Dom declares that he has no conflict of interest. W. Tjalma declares that he has no conflict of interest. G. Van Raemdonck declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Funding

GVR and MD were supported by a doctoral fellowship from the Institute for Science and Technology Flanders (IWT), Ref. no. 093132, and a research project from the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO), Ref. no. G.0597.13, respectively.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Cancer Research UK: Cervical cancer incidence statistics. http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/cervical-cancer/incidence#heading-Ten

- 2.Tjalma WA. There are two prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccines against cancer, and they are different. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(8):964–965. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NCI (2015). http://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/drugs/recombinant-HPV-nonavalent-vaccine

- 4.Chatterjee A. The next generation of HPV vaccines: nonavalent vaccine V503 on the horizon. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014;13(11):1279–1290. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2014.963561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Handler NS, Handler MZ, Majewski S, Schwartz RA. Human papillomavirus vaccine trials and tribulations: vaccine efficacy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5):759–767. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joura EA, Ault KA, Bosch FX, Brown D, Cuzick J, Ferris D, et al. Attribution of 12 high-risk human papillomavirus genotypes to infection and cervical disease. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(10):1997–2008. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castle PE, Maza M. Prophylactic HPV vaccination: past, present, and future. Epidemiol Infect. 2016;144(3):449–468. doi: 10.1017/S0950268815002198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cummings MC, Marquart L, Pelecanos AM, Perkins G, Papadimos D, O’Rourke P, et al. Which are more correctly diagnosed: conventional Papanicolaou smears or Thinprep samples? A comparative study of 9 years of external quality-assurance testing. Cancer Cytopathol. 2015;123(2):108–116. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tjalma WA. The ideal cervical cancer screening recommendation for Belgium, an industrialized country in Europe. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2014;35(3):211–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfstrom KM, Tunesi S, Snijders PJ, Arbyn M, et al. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9916):524–532. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ho GY, Burk RD, Klein S, Kadish AS, Chang CJ, Palan P, et al. Persistent genital human papillomavirus infection as a risk factor for persistent cervical dysplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87(18):1365–1371. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.18.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Renshaw AA. Quality assessment in the age of machine-aided cervical cytology screening. Cancer. 2004;102(6):345–347. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuzick J, Clavel C, Petry KU, Meijer CJ, Hoyer H, Ratnam S, et al. Overview of the European and North American studies on HPV testing in primary cervical cancer screening. Int J Cancer. 2006;119(5):1095–1101. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, Killackey M, Kulasingam SL, Cain J, et al. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;137(4):516–542. doi: 10.1309/AJCPTGD94EVRSJCG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou H, Mody RR, Luna E, Armylagos D, Xu J, Schwartz MR, Mody DR, Ge Y. Clinical performance of the Food and Drug Administration-Approved high-risk HPV test for the detection of high-grade cervicovaginal lesions. Cancer Cytopathol. 2016;124(5):317–323. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Odell LD, Savage EW. Colposcopy. Obstet Gynecol Annu. 1974;3:473–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benevolo M, Allia E, Gustinucci D, Rollo F, Bulletti S, Cesarini E et al (2016) Interobserver reproducibility of cytologic p16INK4a/Ki-67 dual immunostaining in human papillomavirus-positive women. Cancer [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Uijterwaal MH, Polman NJ, Witte BI, van Kemenade FJ, Rijkaart D, Berkhof J, et al. Triaging HPV-positive women with normal cytology by p16/Ki-67 dual-stained cytology testing: baseline and longitudinal data. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(10):2361–2368. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright TC, Behrensb CM, Ranger-Moorec J, Rehmc S, Sharmab A, Stolere MH, Ridderc R. Triaging HPV-positive women with p16/Ki-67 dual-stained cytology: results from a sub-study nested into the ATHENA trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;144(1):51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boulet GA, Horvath CA, Depuydt CE, Bogers JJ. Biomarkers in cervical screening: quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR analysis of P16INK4a expression. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2010;19(1):35–41. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32833233d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peres AL, Paz ESKM, de Araujo RF, de Lima Filho JL, de Melo Junior MR, Martins DB, et al. Immunocytochemical study of TOP2A and Ki-67 in cervical smears from women under routine gynecological care. J Biomed Sci. 2016;23(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s12929-016-0258-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Byun SW, Lee A, Kim S, Choi YJ, Lee YS, Park JS. Immunostaining of p16(INK4a)/Ki-67 and L1 capsid protein on liquid-based cytology specimens obtained from ASC-H and LSIL-H cases. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10(12):1602–1607. doi: 10.7150/ijms.6526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koeneman MM, Kruitwagen RF, Nijman HW, Slangen BF, Van Gorp T, Kruse AJ. Natural history of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a review of prognostic biomarkers. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2015;15(4):527–546. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2015.1012068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ebisch RM, Siebers AG, Bosgraaf RP, Massuger LF, Bekkers RL, Melchers WJ. Triage of high-risk HPV positive women in cervical cancer screening. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2016;16:1–13. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2016.1232166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luttmer R, De Strooper LM, Steenbergen RD, Berkhof J, Snijders PJ, Heideman DA, et al. Management of high-risk HPV-positive women for detection of cervical (pre)cancer. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2016;16(9):961–974. doi: 10.1080/14737159.2016.1217157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arbyn M, Verdoodt F, Snijders PJ, Verhoef VM, Suonio E, Dillner L, et al. Accuracy of human papillomavirus testing on self-collected versus clinician-collected samples: a meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(2):172–183. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70570-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamalet C, Le Retraite L, Leandri FX, Heid P, Sancho Garnier H, Piana L. Vaginal self-sampling is an adequate means of screening HR-HPV types in women not participating in regular cervical cancer screening. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19(1):E44–E50. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Racey CS, Withrow DR, Gesink D. Self-collected HPV testing improves participation in cervical cancer screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Public Health. 2013;104(2):e159–e166. doi: 10.1007/BF03405681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verdoodt F, Jentschke M, Hillemanns P, Racey CS, Snijders PJ, Arbyn M. Reaching women who do not participate in the regular cervical cancer screening programme by offering self-sampling kits: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(16):2375–2385. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ducancelle A, Reiser J, Pivert A, Le Guillou-Guillemette H, Le Duc-Banaszuk AS, Lunel-Fabiani F. Home-based urinary HPV DNA testing in women who do not attend cervical cancer screening clinics. J Infect. 2015;71(3):377–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bosgraaf RP, Verhoef VM, Massuger LF, Siebers AG, Bulten J, de Kuyper-de Ridder GM, et al. Comparative performance of novel self-sampling methods in detecting high-risk human papillomavirus in 30,130 women not attending cervical screening. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(3):646–655. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma’som M, Bhoo-Pathy N, Nasir NH, Bellinson J, Subramaniam S, Ma Y, et al. Attitudes and factors affecting acceptability of self-administered cervicovaginal sampling for human papillomavirus (HPV) genotyping as an alternative to Pap testing among multiethnic Malaysian women. BMJ Open. 2016;6(8):e011022. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-011022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snijders PJ, Verhoef VM, Arbyn M, Ogilvie G, Minozzi S, Banzi R, et al. High-risk HPV testing on self-sampled versus clinician-collected specimens: a review on the clinical accuracy and impact on population attendance in cervical cancer screening. Int J Cancer. 2013;132(10):2223–2236. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmeink CE, Bekkers RL, Massuger LF, Melchers WJ. The potential role of self-sampling for high-risk human papillomavirus detection in cervical cancer screening. Rev Med Virol. 2011;21(3):139–153. doi: 10.1002/rmv.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petignat P, Faltin DL, Bruchim I, Tramer MR, Franco EL, Coutlee F. Are self-collected samples comparable to physician-collected cervical specimens for human papillomavirus DNA testing? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105(2):530–535. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karjalainen L, Anttila A, Nieminen P, Luostarinen T, Virtanen A. Self-sampling in cervical cancer screening: comparison of a brush-based and a lavage-based cervicovaginal self-sampling device. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:221. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2246-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson DC, Bhatta MP, Smith JS, Kempf MC, Broker TR, Vermund SH, et al. Assessment of high-risk human papillomavirus infections using clinician- and self-collected cervical sampling methods in rural women from far western Nepal. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e101255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng JY, Feng MJ, Wu CC, Wang J, Chang TC, Cheng CM. Development of a sampling collection device with diagnostic procedures. Anal Chem. 2016;88(15):7591–7596. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b01269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dijkstra MG, Heideman DA, van Kemenade FJ, Hogewoning KJ, Hesselink AT, Verkuijten MC, et al. Brush-based self-sampling in combination with GP5+/6+-PCR-based hrHPV testing: high concordance with physician-taken cervical scrapes for HPV genotyping and detection of high-grade CIN. J Clin Virol. 2012;54(2):147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gok M, Heideman DA, van Kemenade FJ, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, Spruyt JW, et al. HPV testing on self collected cervicovaginal lavage specimens as screening method for women who do not attend cervical screening: cohort study. BMJ. 2010;340:c1040. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen K, Ouyang Y, Hillemanns P, Jentschke M. Excellent analytical and clinical performance of a dry self-sampling device for human papillomavirus detection in an urban Chinese referral population. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2016;42(12):1839–1845. doi: 10.1111/jog.13132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gok M, Heideman DA, van Kemenade FJ, de Vries AL, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Offering self-sampling for human papillomavirus testing to non-attendees of the cervical screening programme: characteristics of the responders. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(12):1799–1808. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Baars R, Bosgraaf RP, ter Harmsel BW, Melchers WJ, Quint WG, Bekkers RL. Dry storage and transport of a cervicovaginal self-sample by use of the Evalyn Brush, providing reliable human papillomavirus detection combined with comfort for women. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(12):3937–3943. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01506-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lenselink CH, de Bie RP, van Hamont D, Bakkers JM, Quint WG, Massuger LF, et al. Detection and genotyping of human papillomavirus in self-obtained cervicovaginal samples by using the FTA cartridge: new possibilities for cervical cancer screening. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(8):2564–2570. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00285-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gustavsson I, Sanner K, Lindell M, Strand A, Olovsson M, Wikstrom I, et al. Type-specific detection of high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) in self-sampled cervicovaginal cells applied to FTA elute cartridge. J Clin Virol. 2011;51(4):255–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guan Y, Castle PE, Wang S, Li B, Feng C, Ci P, et al. A cross-sectional study on the acceptability of self-collection for HPV testing among women in rural China. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88(7):490–494. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qin Y, Zhang H, Marlowe N, Fei M, Yu J, Lei X, et al. Evaluation of human papillomavirus detection by Abbott m2000 system on samples collected by FTA Elute Card in a Chinese HIV-1 positive population. J Clin Virol. 2016;85:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Venkataraman N, Cole AL, Svoboda P, Pohl J, Cole AM. Cationic polypeptides are required for anti-HIV-1 activity of human vaginal fluid. J Immunol. 2005;175(11):7560–7567. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Di Quinzio MK, Oliva K, Holdsworth SJ, Ayhan M, Walker SP, Rice GE, et al. Proteomic analysis and characterisation of human cervico-vaginal fluid proteins. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;47(1):9–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2006.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dasari S, Pereira L, Reddy AP, Michaels JE, Lu X, Jacob T, et al. Comprehensive proteomic analysis of human cervical-vaginal fluid. J Proteome Res. 2007;6(4):1258–1268. doi: 10.1021/pr0605419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gravett MG, Thomas A, Schneider KA, Reddy AP, Dasari S, Jacob T, et al. Proteomic analysis of cervical-vaginal fluid: identification of novel biomarkers for detection of intra-amniotic infection. J Proteome Res. 2007;6(1):89–96. doi: 10.1021/pr060149v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pereira L, Reddy AP, Jacob T, Thomas A, Schneider KA, Dasari S, et al. Identification of novel protein biomarkers of preterm birth in human cervical-vaginal fluid. J Proteome Res. 2007;6(4):1269–1276. doi: 10.1021/pr0605421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shaw JL, Smith CR, Diamandis EP. Proteomic analysis of human cervico-vaginal fluid. J Proteome Res. 2007;6(7):2859–2865. doi: 10.1021/pr0701658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Andersch-Bjorkman Y, Thomsson KA, Holmen Larsson JM, Ekerhovd E, Hansson GC. Large scale identification of proteins, mucins, and their O-glycosylation in the endocervical mucus during the menstrual cycle. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6(4):708–716. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600439-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Klein LL, Jonscher KR, Heerwagen MJ, Gibbs RS, McManaman JL. Shotgun proteomic analysis of vaginal fluid from women in late pregnancy. Reprod Sci. 2008;15(3):263–273. doi: 10.1177/1933719107311189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zegels G, Van Raemdonck GA, Coen EP, Tjalma WA, Van Ostade XW. Comprehensive proteomic analysis of human cervical-vaginal fluid using colposcopy samples. Proteome Sci. 2009;7:17. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-7-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zegels G, Van Raemdonck GA, Tjalma WA, Van Ostade XW. Use of cervicovaginal fluid for the identification of biomarkers for pathologies of the female genital tract. Proteome Sci. 2010;8:63. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-8-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Panicker G, Lee DR, Unger ER. Optimization of SELDI-TOF protein profiling for analysis of cervical mucous. J Proteomics. 2009;71(6):637–646. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Panicker G, Ye Y, Wang D, Unger ER. Characterization of the human cervical mucous proteome. Clin Proteomics. 2010;6(1–2):18–28. doi: 10.1007/s12014-010-9042-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Burgener A, Rahman S, Ahmad R, Lajoie J, Ramdahin S, Mesa C, et al. Comprehensive proteomic study identifies serpin and cystatin antiproteases as novel correlates of HIV-1 resistance in the cervicovaginal mucosa of female sex workers. J Proteome Res. 2011;10(11):5139–5149. doi: 10.1021/pr200596r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liong S, Di Quinzio MK, Heng YJ, Fleming G, Permezel M, Rice GE, et al. Proteomic analysis of human cervicovaginal fluid collected before preterm premature rupture of the fetal membranes. Reproduction. 2013;145(2):137–147. doi: 10.1530/REP-12-0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lo JO, Reddy AP, Wilmarth PA, Roberts VH, Kinhnarath A, Snyder J, et al. Proteomic analysis of cervical vaginal fluid proteins among women in recurrent preterm labor. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27(12):1183–1188. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.852172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Van Raemdonck GA, Tjalma WA, Coen EP, Depuydt CE, Van Ostade XW. Identification of protein biomarkers for cervical cancer using human cervicovaginal fluid. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e106488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Van Raemdonck G, Zegels G, Coen E, Vuylsteke B, Jennes W, Van Ostade X. Increased Serpin A5 levels in the cervicovaginal fluid of HIV-1 exposed seronegatives suggest that a subtle balance between serine proteases and their inhibitors may determine susceptibility to HIV-1 infection. Virology. 2014;458–459:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boylan KL, Afiuni-Zadeh S, Geller MA, Hickey K, Griffin TJ, Pambuccian SE, et al. A feasibility study to identify proteins in the residual Pap test fluid of women with normal cytology by mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Clin Proteomics. 2014;11(1):30. doi: 10.1186/1559-0275-11-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Verhoef VM, Dijkstra MG, Bosgraaf RP, Hesselink AT, Melchers WJ, Bekkers RL, et al. A second generation cervico-vaginal lavage device shows similar performance as its preceding version with respect to DNA yield and HPV DNA results. BMC Womens Health. 2013;13:21. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-13-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Khan AM, Sasieni P, Singer A. A prospective double-blind cross-sectional study of the accuracy of the use of dry vaginal tampons for self-sampling of human papillomaviruses. BJOG. 2015;122(3):388–394. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Othman NH, Mohamad Zaki FH. Self-collection tools for routine cervical cancer screening: a review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(20):8563–8569. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.20.8563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marlow LA, Waller J, Wardle J. Barriers to cervical cancer screening among ethnic minority women: a qualitative study. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2015;41(4):248–254. doi: 10.1136/jfprhc-2014-101082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Waller J, Bartoszek M, Marlow L, Wardle J. Barriers to cervical cancer screening attendance in England: a population-based survey. J Med Screen. 2009;16(4):199–204. doi: 10.1258/jms.2009.009073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arrossi S, Ramos S, Straw C, Thouyaret L, Orellana L. HPV testing: a mixed-method approach to understand why women prefer self-collection in a middle-income country. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:832. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3474-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Levinson KL, Abuelo C, Salmeron J, Chyung E, Zou J, Belinson SE, et al. The Peru Cervical Cancer Prevention Study (PERCAPS): the technology to make screening accessible. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;129(2):318–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rao J, Escobar-Hoyos L, Shroyer KR. Unmet clinical needs in cervical cancer screening. MLO Med Lab Obs. 2016;48(1):8, 10, 4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Quesada-Gonzalez D, Merkoci A. Nanoparticle-based lateral flow biosensors. Biosens Bioelectron. 2015;73:47–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2015.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Huang X, Aguilar ZP, Xu H, Lai W, Xiong Y. Membrane-based lateral flow immunochromatographic strip with nanoparticles as reporters for detection: a review. Biosens Bioelectron. 2016;75:166–180. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2015.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Koczula KM, Gallotta A. Lateral flow assays. Essays Biochem. 2016;60(1):111–120. doi: 10.1042/EBC20150012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xu Y, Liu Y, Wu Y, Xia X, Liao Y, Li Q. Fluorescent probe-based lateral flow assay for multiplex nucleic acid detection. Anal Chem. 2014;86(12):5611–5614. doi: 10.1021/ac5010458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Figueroa CJC, Verster A, Dalal S, Baggaley R (eds) (2016) Systematic review on HIV self-testing (HIVST) performance and accuracy of results. In: 21st International AIDS Conference. Durban (18–22 July 2016)

- 79.Witzel TC, Rodger AJ. New initiatives to develop self-testing for HIV. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2017;30(1):50–57. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Figueroa C, Johnson C, Verster A, Baggaley R. Attitudes and acceptability on HIV self-testing among key populations: a literature review. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(11):1949–1965. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1097-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stanczuk G, Baxter G, Currie H, Lawrence J, Cuschieri K, Wilson A, et al. Clinical validation of hrHPV testing on vaginal and urine self-samples in primary cervical screening (cross-sectional results from the Papillomavirus Dumfries and Galloway-PaVDaG study) BMJ Open. 2016;6(4):e010660. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jentschke M, Soergel P, Hillemanns P. Evaluation of a multiplex real time PCR assay for the detection of human papillomavirus infections on self-collected cervicovaginal lavage samples. J Virol Methods. 2013;193(1):131–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sanner K, Wikstrom I, Gustavsson I, Wilander E, Lindberg JH, Gyllensten U, et al. Daily self-sampling for high-risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV) testing. J Clin Virol. 2015;73:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kim YI, Giuliano A, Hatch KD, Schneider A, Nour MA, Dallal GE, et al. Global DNA hypomethylation increases progressively in cervical dysplasia and carcinoma. Cancer. 1994;74(3):893–899. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940801)74:3<893::AID-CNCR2820740316>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Widschwendter A, Gattringer C, Ivarsson L, Fiegl H, Schneitter A, Ramoni A, et al. Analysis of aberrant DNA methylation and human papillomavirus DNA in cervicovaginal specimens to detect invasive cervical cancer and its precursors. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(10):3396–3400. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sun C, Reimers LL, Burk RD. Methylation of HPV16 genome CpG sites is associated with cervix precancer and cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121(1):59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Doufekas K, Zheng SC, Ghazali S, Wong M, Mohamed Y, Jones A et al (2016) DNA methylation signatures in vaginal fluid samples for detection of cervical and endometrial cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer [DOI] [PubMed]

- 88.Zavesky L, Jandakova E, Turyna R, Langmeierova L, Weinberger V, Minar L, et al. New perspectives in diagnosis of gynaecological cancers: emerging role of circulating microRNAs as novel biomarkers. Neoplasma. 2015;62(4):509–520. doi: 10.4149/neo_2015_062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Verhoef VM, Bosgraaf RP, van Kemenade FJ, Rozendaal L, Heideman DA, Hesselink AT, et al. Triage by methylation-marker testing versus cytology in women who test HPV-positive on self-collected cervicovaginal specimens (PROHTECT-3): a randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(3):315–322. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Verhoef VM, Heideman DA, van Kemenade FJ, Rozendaal L, Bosgraaf RP, Hesselink AT, et al. Methylation marker analysis and HPV16/18 genotyping in high-risk HPV positive self-sampled specimens to identify women with high grade CIN or cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;135(1):58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.De Strooper LM, Verhoef VM, Berkhof J, Hesselink AT, de Bruin HM, van Kemenade FJ, et al. Validation of the FAM19A4/mir124-2 DNA methylation test for both lavage- and brush-based self-samples to detect cervical (pre)cancer in HPV-positive women. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;141(2):341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Honegger A, Leitz J, Bulkescher J, Hoppe-Seyler K, Hoppe-Seyler F. Silencing of human papillomavirus (HPV) E6/E7 oncogene expression affects both the contents and the amounts of extracellular microvesicles released from HPV-positive cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2013;133(7):1631–1642. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chiantore MV, Mangino G, Iuliano M, Zangrillo MS, De Lillis I, Vaccari G, et al. Human papillomavirus E6 and E7 oncoproteins affect the expression of cancer-related microRNAs: additional evidence in HPV-induced tumorigenesis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142(8):1751–1763. doi: 10.1007/s00432-016-2189-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Liu J, Sun H, Wang X, Yu Q, Li S, Yu X, et al. Increased exosomal microRNA-21 and microRNA-146a levels in the cervicovaginal lavage specimens of patients with cervical cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15(1):758–773. doi: 10.3390/ijms15010758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang J, Liu SC, Luo XH, Tao GX, Guan M, Yuan H, et al. Exosomal long noncoding RNAs are differentially expressed in the cervicovaginal lavage samples of cervical cancer patients. J Clin Lab Anal. 2016;30(6):1116–1121. doi: 10.1002/jcla.21990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.McDicken IW, McMillan DL, Rainey M. Carcinoembryonic antigen levels in cervico-vaginal fluid from patients with intra-epithelial and invasive carcinoma of the cervix. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1982;18(10):917–919. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(82)90237-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Harlozinska A, Kula J, Stepinska B, Jelen M, Richter R, Slesak B. Cervical carcinoma antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and nonspecific cross-reacting antigen (NCA) in appraisal of uterine cervix smears. Am J Clin Pathol. 1985;83(3):301–307. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/83.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fujii S, Konishi I, Nanbu Y, Nonogaki H, Kobayashi F, Sagawa N, et al. Analysis of the levels of CA125, carcinoembryonic antigen, and CA19-9 in the cervical mucus for a detection of cervical adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 1988;62(3):541–547. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880801)62:3<541::AID-CNCR2820620317>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nanbu Y, Fujii S, Konishi I, Nonogaki H, Sagawa N, Kobayashi F, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of CA130 in fetal tissues, and in normal and neoplastic tissues of the female genital tract. Asia Oceania J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;16(4):379–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.1990.tb00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sarandakou A, Kontoravdis A, Kontogeorgi Z, Rizos D, Phocas I. Expression of CEA, CA-125 and SCC antigen by biological fluids associated with pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1992;44(3):215–220. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(92)90102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sarandakou A, Phocas I, Botsis D, Sikiotis K, Rizos D, Kalambokis D, et al. Tumour-associated antigens CEA, CA125, SCC and TPS in gynaecological cancer. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1998;19(1):73–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sarandakou A, Phocas I, Botsis D, Rizos D, Trakakis E, Chryssikopoulos A. Vaginal fluid and serum CEA, CA125 and SCC in normal conditions and in benign and malignant diseases of the genital tract. Acta Oncol. 1997;36(7):755–759. doi: 10.3109/02841869709001350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Calis P, Yuce K, Basaran D, Salman C. Assessment of cervicovaginal cancer antigen 125 levels: a preliminary study for endometrial cancer screening. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2016;81(6):518–522. doi: 10.1159/000444321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tjiong MY, Schegget JT, Tjiong AHSP, Out TA, Van Der Vange N, Burger MP, et al. IgG antibodies against human papillomavirus type 16 E7 proteins in cervicovaginal washing fluid from patients with cervical neoplasia. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2000;10(4):296–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2000.010004296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tjiong MY, Zumbach K, Schegget JT, van der Vange N, Out TA, Pawlita M, et al. Antibodies against human papillomavirus type 16 and 18 E6 and E7 proteins in cervicovaginal washings and serum of patients with cervical neoplasia. Viral Immunol. 2001;14(4):415–424. doi: 10.1089/08828240152716655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tjiong MY, van der Vange N, ten Kate FJ, Tjong AHSP, ter Schegget J, Burger MP, et al. Increased IL-6 and IL-8 levels in cervicovaginal secretions of patients with cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;73(2):285–291. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1999.5358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tjiong MY, van der Vange N, ter Schegget JS, Burger MP, ten Kate FW, Out TA. Cytokines in cervicovaginal washing fluid from patients with cervical neoplasia. Cytokine. 2001;14(6):357–360. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2001.0909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tota JE, Ramana-Kumar AV, El-Khatib Z, Franco EL. The road ahead for cervical cancer prevention and control. Curr Oncol. 2014;21(2):E255–E264. doi: 10.3747/co.21.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wentzensen N, Silver MI. Biomarkers for cervical cancer prevention programs: the long and winding road from discovery to clinical use. J Low Genit Tract Di. 2016;20(3):191–194. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Honda K, Yamada T, Endo R, Ino Y, Gotoh M, Tsuda H, et al. Actinin-4, a novel actin-bundling protein associated with cell motility and cancer invasion. J Cell Biol. 1998;140(6):1383–1393. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.6.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Honda K, Yamada T, Hayashida Y, Idogawa M, Sato S, Hasegawa F, et al. Actinin-4 increases cell motility and promotes lymph node metastasis of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(1):51–62. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hayashida Y, Honda K, Idogawa M, Ino Y, Ono M, Tsuchida A, et al. E-cadherin regulates the association between beta-catenin and actinin-4. Cancer Res. 2005;65(19):8836–8845. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]