Abstract

Background and objective

Umbilical cord blood (UCB) is a valuable stem cell source used for transplantation. Immediate umbilical cord (UC) clamping is widely practised, but delayed UC clamping is increasingly advocated to reduce possible infant anaemia. The aim of this study was to investigate an intermediate UC clamping time point and to evaluate iron status at the age of 4 months in infants who had the UC clamped after 60 s and compare the results with immediate and late UC clamping.

Design

Prospective observational study with two historical controls.

Setting

A university hospital in Stockholm, Sweden, and a county hospital in Halland, Sweden.

Methods

Iron status was assessed at 4 months in 200 prospectively recruited term infants whose UC was clamped 60 s after birth. The newborn baby was held below the uterine level for the first 30 s before placing the infant on the mother’s abdomen for additional 30 s. The results were compared with data from a previously conducted randomised controlled trial including infants subjected to UC clamping at ≤10 s (n=200) or ≥180 s (n=200) after delivery.

Results

After adjustment for age differences at the time of follow-up, serum ferritin concentrations were 77, 103 and 114 µg/L in the 10, 60 and 180 s groups, respectively. The adjusted ferritin concentration was significantly higher in the 60 s group compared with the 10 s group (P=0.002), while the difference between the 60 and 180 s groups was not significant (P=0.29).

Conclusion

In this study of healthy term infants, 60 s UC clamping with 30 s lowering of the baby below the uterine level resulted in higher serum ferritin concentrations at 4 months compared with 10 s UC clamping. The results suggest that delaying the UC clamping for 60 s reduces the risk for iron deficiency.

Trial registration number

Keywords: paediatrics, umbilical cord clamping, iron deficiency, fetal medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study compares iron status and blood status at the age of 4 months in children whose umbilical cords (UCs) were clamped after 60 s with children whose UCs were clamped ≤10 or ≥180 s.

In this study, we focus on potential consequences for the child caused by different UC clamping times, and not the quality of the collected UC blood.

This prospective observational study uses historical controls and results should be interpreted with caution because of potential confounding bias.

We did not use a non-inferiority approach for this study since we aimed to compare results after 60 s UC clamping with both 10 and 180 s UC clamping.

Introduction

During the last decades, immediate umbilical cord (UC) clamping has been a part of active management of labour with the aim to reduce maternal haemorrhage at birth.1 2 Hence, the placenta and umbilical cord blood (UCB) have been regarded as waste products following birth. However, immediate UC clamping may deprive infants of up to one-third of the total fetoplacental blood volume,3 4 and increase the risk of iron deficiency (ID) in the first 3–6 months of life.5–9 ID is associated with impaired neurodevelopment affecting cognitive, motor and behavioural skills in young children.10–12 For this reason, WHO recommends delayed UC clamping for 1–3 min after birth.13

On the other side, UCB is a valuable stem cell source for the 30%–50% of patients who need a haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, but who lack a suitable family or public registry donor.14 15 Therefore, UCB is collected and stored in altruistic and private UCB banks. The earlier the UC is clamped, the more blood is left to collect from the placenta, and for this reason immediate UC clamping is normally practised in UCB collection. More than 35 000 transplantations with UCB have been performed worldwide.14

We hypothesised that if the UC is clamped at 60 s after birth, a sufficient amount of blood will have passed from the placenta to the infant to reduce the risk of ID and anaemia while still allowing collection of UCB for banking.16 The objective of the current study was to evaluate iron status and complete blood counts at the age of 4 months in infants who had the UC clamped after 60 s and compare the results with immediate (≤10 s) and late (≥180 s) UC clamping. In this study, we focused on potential consequences for the donors only.

Materials and methods

We performed an observational cohort study using one prospective clinical cohort and data from a previously performed randomised controlled trial (RCT).6 The prospectively recruited infants were born at Karolinska University Hospital, Huddinge, Sweden, between April 2012 and May 2015, to parents who agreed to donate UCB to the Swedish National Umbilical Cord Blood Bank, a public bank without profit interest. The UC was clamped after 60±10 s. The newborn baby was held below the uterine level for the first 30 s before placing the infant on the mother’s abdomen for additional 30 s. The historical cohorts consisted of data from infants who were randomised to immediate (within 10 s after birth) or late (after 180 s) UC clamping, respectively, in a trial conducted by three of the coauthors at the Hospital of Halland in Halmstad, Sweden, between April 2008 and September 2009.6

Outcome measures

The primary outcome variable was ferritin as a measure of iron stores, at the age of 4 months, and secondary outcomes included haemoglobin, transferrin saturation, soluble transferrin receptors, mean cell volume (MCV) as well as ID (defined as ≥2 iron indicators outside reference range with the following cut-off values: ferritin <20 µg/L,17 MCV <73 fL,17 transferrin saturation <10%18 and transferrin receptor >7 mg/L6). Since ferritin is an acute phase reactant, C reactive protein (CRP) was analysed in order to exclude falsely elevated ferritin measurements. The infant’s dietary habits at 4 months were also considered as well as the relevance of infant sex for iron and blood status at that age.

Sample size

A formal power calculation was not performed for the current study, but the sample size was based on the group size in the original RCT by Andersson et al (the historical cohorts).6 The power calculation by Andersson et al showed that a group size of 200 would enable detection of a 29% difference in geometric mean serum ferritin between 10 and 180 s UC clamping with a power of 80% and a significance level of 0.05, assuming a mean serum ferritin concentration of 110 µg/L in the 180 s group while allowing an attrition of 25%.6 Based on the results from Andersson et al, demonstrating a 45% difference in ferritin concentration between 10 and 180 s UC clamping, we decided to include 200 children also in the prospective group.

Study population and inclusion criteria

The same inclusion criteria applied for the prospective and historical cohorts: healthy mother, normal, singleton pregnancy, gestational age 37+0 to 41+6 weeks and planned vaginal delivery with cephalic presentation.6 The mother also had to understand Swedish well enough to consent participation in the study. In the prospectively recruited cohort, parents also had to agree to altruistic donation of UCB, and to the modified UC clamping strategy. Exclusion criteria were also the same in the three groups: smoking mother, serious congenital malformations, syndromes or other congenial diseases that could affect the outcome measures. For this study, we only included data from the RCT that were handled according to per protocol, as compared with the analysis by intention to treat in the original RCT.6 Moreover, like the RCT, we only included children with CRP <10 in the analysis. All parents donating UCB at Karolinska University Hospital, Huddinge, that met the inclusion criteria were offered to participate in the study on arrival at the delivery unit. Midwives were instructed to clamp the UC 60 s after birth in deliveries where parents had consented to participate in the study. Staff in charge of collection of UCB measured the exact timing of UC clamping using a digital timer. Only children whose UCs were clamped at 60±10 s were included in the study. Oral and written informed consent was obtained from one or both of the parents.

Data collection and blood samples

Midwives were instructed to hold the newborn baby below the uterine level for the first 30 s before placing the infant on the mother’s abdomen, in accordance with the study by Andersson et al.6 The UC clamping technique used in the prospectively recruited cohort was similar to the historical groups except for the timing. Venous blood samples were analysed at birth from the UC, at 2–3 days of age in connection with metabolic screening and at 4 months (±21 days) at a scheduled follow-up visit. At birth and at 4 months, serum ferritin, haemoglobin, haematocrit, MCV, reticulocyte count, transferrin saturation, transferrin receptor and CRP were analysed, and at 2–3 days of age we analysed haemoglobin, haematocrit and bilirubin. EDTA tubes were used for blood count and serum separator tubes for iron status, bilirubin and CRP (Microvette, Sarstedt AG & Co, Nümbrecht, Germany). Blood status was analysed using equal methods and equipment in both the laboratory at Karolinska University Hospital (Sysmex XE5000, Sysmex, Kobe, Japan) and at the Hospital of Halland (Sysmex XE2100, Sysmex, Kobe, Japan). Analysis of iron status and CRP could be performed at the same laboratory as in the RCT,6 and therefore the blood samples collected at Karolinska University Hospital were centrifuged and the serum kept at −70°C before sent for analysis at the Clinical Chemistry Laboratory at the Hospital of Halland. The samples were then thawed and analysed using a Cobas 6000 (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland), the same method as in the RCT.6

Statistical analysis

Analyses on the two historical cohorts, 10 and 180 s, were calculated only on infants receiving intervention per protocol in order to obtain clearly defined groups according to time of UC clamping. Baseline characteristics were compared across groups using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Means of outcome measures in the three cohorts were compared using the Bonferroni method. We also performed pairwise comparisons (60 s vs 10 s and 60 s vs 180 s) using Student’s t-test for variables with normal distribution that were statistically significant in the Bonferroni analyses. Ferritin concentration was log10 transformed for analysis because of skewed distribution, and the results were presented as geometric means. Categorical variables were compared between groups using Fisher’s exact test for pairwise comparisons. Adjusted group means were compared using ANOVA, and a binary logistic regression model was used to adjust for sex and age in the evaluation of ID at 4 months. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant. No imputation of missing data was performed. Loss to follow-up was registered, but not examined further. IBM SPSS for Windows, V.22, was used for the analyses.

Results

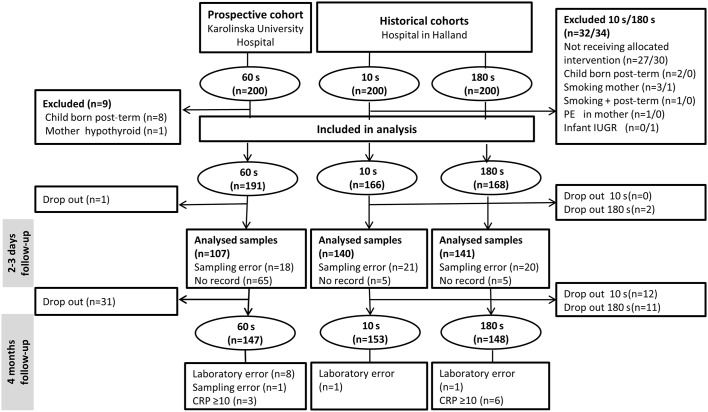

Of the 200 prospectively recruited infants, 191 were included in the analysis as compared with 166 in the 10 s and 168 in the 180 s groups. Infants lost to follow-up or excluded due to not fulfilling inclusion criteria are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study populations. CRP, C reactive protein; IUGR, intrauterine growth retardation; PE, pre-eclampsia.

Baseline data

There were no significant differences in the 60 s group as compared with the 10 and 180 s groups with regard to maternal or neonatal characteristics. The 10 s group had higher UC haemoglobin (16.3 vs 15.3 g/dL, P<0.001) and higher UC haematocrit (48.7% vs 47.0%, P=0.005) than the 60 s group. There were no significant differences between the 60 s and the 180 s groups (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of mothers and infants according to time for umbilical cord clamping

| Umbilical cord clamping time | P value | |||

| 10 s (n=166 (HC)) |

60 s (n=191) | 180 s (n=168 (HC)) | ||

| Maternal characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | 31.7 (4.2) | 30.7 (4.7) | 30.8 (4.9) | NS |

| Parity (including study child) | 1.81 (0.87) | 1.86 (0.76) | 1.76 (0.74) | NS |

| Weight at first antenatal visit (kg) | 66.4 (12.0) | 67.3 (11.5) | 67.3 (12.1) | NS |

| Body mass index | 23.6 (3.8) | 24.5 (3.9) | 23.9 (3.6) | NS |

| Haemoglobin at first antenatal visit (g/dL) | 12.8 (9) | 12.8 (10) | 12.8 (11) | NS |

| Number (%) of vaginal deliveries | ||||

| Non-instrumental | 157 (95) | 184 (96) | 157 (94) | NS |

| Vacuum extraction | 8 (5) | 7 (4) | 11 (7) | NS |

| Forceps | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NS |

| Infant characteristics | ||||

| Gestational age (weeks) | 40.0 (1.1) | 40.0 (1.0) | 40.0 (1.1) | NS |

| Number (%) of males | 83 (50) | 98 (51) | 73 (43) | NS |

| Birth weight (g) | 3523 (483) | 3603 (454) | 3633 (464) | NS |

| Birth length (cm) | 50.7 (1.9) | 50.6 (1.8) | 50.9 (1.9) | NS |

| Head circumference (cm) | 34.7 (1.3) | 35.1 (1.3) | 35.0 (1.4) | NS |

| Umbilical cord haemoglobin (g/L) | 163 (15) | 153 (20) | 158 (18) | <0.001* |

| Umbilical cord haematocrit (%) | 48.7 (4.3) | 47.0 (5.5) | 47.1 (5.0) | 0.005** |

Values are means (SD) unless stated otherwise. P<0.05 was considered significant.

*Comparison of 10 and 60 s. For 180 and 60 s, P=0.063.

**Comparison of 10 and 60 s. For 180 and 60 s, P>0.99.

HC, historical cohort; NS, non-significant.

Two-day to 3-day follow-up

At 2–3 days, blood samples were obtained from 140 infants in the 10 s group, 107 in the 60 s group and 141 in the 180 s group (figure 1). The prevalence of anaemia was higher in the 10 s compared with the 60 and 180 s groups (9 (6.4%), 2 (1.9%) and 2 (1.4%)), respectively (P=0.04). Haemoglobin was lower in the 10 and 60 s groups compared with the 180 s group; 17.5, 18.0 and 18.9 g/dL, respectively (P=0.001 for 60 s vs 180 s). Bilirubin did not differ between the groups. Anaemic children were referred for further diagnostics but none needed treatment.

Primary outcome

In total, 468 (78%) infants had follow-up at 4 months (children excluded or lost to follow-up are shown in figure 1). In the 60 s group, the infants (n=147) were 4 days older than the historical groups from the RCT (126±7 days vs 122±6 days, P<0.001). The geometric mean ferritin levels were 80, 96 and 117 µg/L, respectively, in the 10, 60 and 180 s groups (P=0.052 for 10 s vs 60 s; P=0.02 for 60 s vs 180 s) (table 2). After adjustment for the age difference, the geometric means were 77, 103 and 114 µg/L, respectively (P=0.002 for 10 s vs 60 s; P=0.29 for 60 s vs 180 s) (table 3).

Table 2.

Outcome measures at the age of 4 months in infants whose umbilical cords were clamped after 10, 60 or 180 s

| Umbilical cord clamping time | 60 s vs 10 s | 60 s vs 180 s | |||||

| 10 s (n=153 (HC)) |

60 s (n=147) |

180 s (n=148 (HC)) |

Mean difference (95% CI) | P value | Mean difference (95% CI) | P value | |

| Infant age (days) | 122 (6) | 126 (7) | 122 (6) | 5 (3 to 6) | <0.001 | 4 (3 to 6) | <0.001 |

| Main outcome measures | |||||||

| Geometric mean (range) ferritin (μg/L) | 80 (33 to 191) | 96 (44 to 208) | 117 (58 to 232) | 0.83 (0.69 to 1.45)* | 0.052 | 1.21 (1.03 to 1.44)* | 0.02 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.3 (7) | 11.5 (8) | 11.3 (8) | 2 (0 to 4) | 0.047 | 2 (0 to 4) | 0.03 |

| Blood count | |||||||

| Haematocrit (%) | 33.0 (2.0) | 33.3 (2.2) | 32.7 (2.1) | 0.3 (−0.2 to 0.8) | 0.19 | 1 (0 to 1) | 0.02 |

| Mean cell volume (fL) | 77.9 (3.1) | 77.7 (3.7) | 79.2 (3.0) | −0.2 (−1 to 0.6) | 0.67 | −1.5 (−2.3 to −0.7) | <0.001 |

| Reticulocyte count (×1012/L) | 0.037 (11) | 0.036 (11) | 0.040 (11) | −1 (−4 to 1) | 0.39 | −4 (−6 to −1) | 0.01 |

| Iron status | |||||||

| Transferrin receptor (mg/L) | 4.00 (0.80) | 4.07 (0.92) | 3.71 (0.69) | 0.07 (−0.13 to 0.26) | 0.51 | 0.35 (0.17 to 0.54) | <0.001 |

| Transferrin saturation (%) | 16 (6) | 16 (8) | 18 (6) | 1 (−1 to 2) | 0.40 | −2 (−3 to 0) | 0.03 |

Values are means (SD) unless stated otherwise.

Successful analyses in the 60 and 180 s groups: haemoglobin (n=140, 144), haematocrit, mean cell volume, reticulocyte count (n=135, 144), ferritin (n=147, 148), transferrin receptor (n=147, 148), transferrin saturation (n=145, 148).

*Geometric mean ratio (95% CI for geometric mean).

HC, Historical cohort.

Table 3.

Outcome measures at the age of 4 months adjusted for infant age

| Umbilical cord clamping time (adjusted means (95% CI)) | P value | ||||

| 10 s (n=152 (HC)) |

60 s (n=147) |

180 s (n=148 (HC)) |

60 s vs 10 s | 60 s vs 180 s | |

| Main outcome measures | |||||

| Geometricmean (range) ferritin (μg/L) | 77 (68 to 87) | 103 (90 to 117) | 114 (100 to 129) | 0.002 | 0.29 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.3 (11.2 to 11.5) | 11.4 (11.3 to 11.6) | 11.3 (11.2 to 11.4) | 0.30 | 0.17 |

| Blood count | |||||

| Haematocrit (%) | 33.1 (32.7 to 33.4) | 33.1 (32.8 to 33.5) | 32.7 (32.4 to 33.1) | 0.30 | 0.12 |

| Mean cell volume (fL) | 77.8 (77.3 to 78.3) | 77.9 (77.3 to 78.4) | 79.1 (78.6 to 79.6) | 0.30 | 0.003 |

| Reticulocyte count (×1012/L) | 0.037 (0.035 to 0.039) | 0.037 (0.035 to 0.039) | 0.039 (0.038 to 0.041) | 0.99 | 0.07 |

| Iron status | |||||

| Transferrin receptor (mg/L) | 4.01 (3.87 to 4.14) | 4.05 (3.92 to 4.19) | 3.72 (3.59 to 3.85) | 0.62 | 0.001 |

| Transferrin saturation (%) | 15.7 (14.7 to 16.7) | 16.6 (15.5 to 17.7) | 18.1 (17 to 19.2) | 0.25 | 0.06 |

Values are means (95% CI) adjusted for infant age (days from birth) unless stated otherwise.

Successful analyses for the 60 s group: ferritin (n=147), haemoglobin (n=140), haematocrit, mean cell volume, reticulocyte count (n=135), transferrin receptor and transferrin saturation (n=145). For the 180 s group, blood status (n=144).

HC, historical cohort.

Secondary outcomes

All secondary outcome variables are shown in table 2. Haemoglobin levels at 4 months were higher in the 60 s group compared with 10 and 180 s, but the difference did not remain in the age-adjusted model (table 3). There were no statistically significant differences in the prevalence of anaemia in the 60 s group as compared with the other two groups (table 4). After adjustment for age at the time of follow-up, there were no differences between the 10 and 60 s groups in haematocrit, MCV, reticulocyte count, transferrin receptor or transferrin saturation. The 60 s group had significantly lower adjusted MCV and higher adjusted transferrin receptor compared with the 180 s group, but there were no differences in haematocrit, reticulocyte count or transferrin saturation (table 3). The prevalence of ID was 8 (5.2%), 7 (4.8%) and 1 (0.7%), respectively, in the 10, 60 and 180 s groups (P>0.99 for 10 s vs 60 s and P=0.04 for 60 s vs 180 s) (table 4). After statistical adjustments for sex and age at the time of follow-up, the prevalence of ID did not differ between the 60 s group and the two other groups. The proportion of infants that were exclusively breast fed at 4 months did not differ between the groups (79 (52%), 92 (58%) and 89 (56%), respectively, in the 10, 60 and 180 s groups). The impact of exclusive breast feeding on ferritin concentration and ID was further assessed in an adjusted model, but no correlation was found (data not shown).

Table 4.

Infants with iron status indicators outside reference limits at the age of 4 months according to umbilical cord clamping time

| Umbilical cord clamping time | P value | ||||

| 10 s (n=153 (HC)) |

60 s (n=147) |

180 s (n=148 (HC)) |

60 s vs 10 s | 60 s vs 180 s | |

| Ferritin <20 µg/L | 11 (7.2) | 4 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 0.11 | 0.06 |

| Anaemia (haemoglobin <10.5 g/dL) | 20 (13.1) | 16 (11.4) | 20 (13.9) | 0.72 | 0.60 |

| Mean cell volume <73 fL | 8 (5.2) | 14 (10.4) | 3 (2.1) | 0.12 | 0.01 |

| Transferrin saturation <10% | 22 (14.4) | 15 (10.3) | 8 (5.4) | 0.38 | 0.13 |

| Transferrin receptor >7 mg/L | 0 (0) | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 0.24 | 0.25 |

| Iron deficiency* | 8 (5.2) | 7 (4.8) | 1 (0.7) | 1.00 | 0.04 |

Values are unadjusted numbers (%). *Defined as ≥ 2 iron indicators (low ferritin, low mean cell volume, low transferrin saturation, high transferrin receptor) outside reference range.

Numbers of successful analyses: mean cell volume (n=153, 135, 144), transferrin saturation (n=153, 145, 148), anaemia (n=153, 140, 144).

HC, historical cohort.

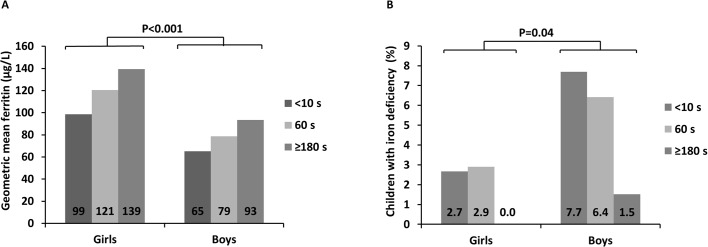

Sex differences

Iron status and blood status at 4 months were further assessed by analysing differences according to infant sex. When data from the three cohorts were analysed together, geometric mean ferritin was lower in boys than in girls, and ID was more prevalent among boys (figure 2A,B). Haemoglobin concentrations did not differ significantly between boys and girls and neither did the prevalence of anaemia (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Differences in infants’ iron status at the age of 4 months according to sex in three groups divided according to umbilical cord clamping time. (A) Geometric mean ferritin according to sex and time for umbilical cord clamping. (B) Proportion of children with iron deficiency according to time for umbilical cord clamping and sex.

Discussion

We compared infants’ iron and blood status at the age of 4 months after three different UC clamping time intervals (60 s vs ≤10 s, and ≥180 s, respectively). Previous studies have compared immediate and late UC clamping, but the definition of ‘late’ in these studies varies from 60 to 180 s or after birth of the placenta.5 7 8 The current study evaluates an intermediate UC clamping strategy that can be used in connection with altruistic donation of UCB for clinical banking. When asking parents to donate their child’s UCB for the potential good of others, it is essential to inform of possible consequences for the child. We demonstrated that after adjustment for age difference at the time of follow-up, there were no statistically significant differences in ferritin concentration between the 60 and 180 s groups, but the 60 s group had significantly higher ferritin concentrations compared with 10 s. The main reason for the effect of age on ferritin during infancy is rapid growth that leads to a rapidly expanding blood volume and depletion of iron stores.9

Results from the present study are in accordance with a Brazilian RCT that demonstrated higher ferritin concentration at the age of 3 months in children whose UCs were clamped after 60 s compared with immediate UC clamping.19 However, our findings are in contrast to a study by Ceriani Cernadas et al, who reported no differences in ferritin 6 months after birth comparing 15 and 60 s UC clamping. The difference in ferritin between the 60 and 180 s groups was not presented.20 This study indicates that a 60 s delay before UC clamping results in a mean serum ferritin at 4 months of age corresponding to 90% of the mean ferritin after 180 s UC clamping.

In the current study, children in the 60 s group had the lowest haemoglobin of all three groups at birth (10 s 16.3 g/dL, 60 s 15.3 g/dL, 180 s 15.8 g/dL) but at 4 months, there were no longer any differences between the groups in our adjusted model. The original RCT as well as a Cochrane report found higher concentrations of haemoglobin after immediate than late UC clamping at birth.6 8 As speculated in a previous publication, this difference may not reflect true difference in haemoglobin but could be a result of transendothelial plasma leakage in the UC after UC clamping.6

The prevalence of ID was higher in the 10 and 60 s groups compared with the 180 s group. However, when adjusting for sex and age at the time of follow-up, there were no longer any statistically significant differences between the three groups. In accordance with previous studies on ID in infancy, we found that at 4 months, boys had significantly lower geometric mean ferritin and more often ID than girls.21 22 Nevertheless, the aim of the study was not to compare differences according to sex, and the groups were therefore too small to draw any reliable conclusions of sex and ID. It has been suggested that the differences in iron status between the two sexes may be hormone related, but it is also influenced by genetic factors, which may differ in populations with different ethnicity.22 Also, when considering the generalisability of this study, readers should bear in mind that all children were placed below the uterine level for 30 s directly after birth. This may be in contrast to the practice in other delivery settings, where the children are often placed directly on the woman’s abdomen, which may affect the speed of the placental transfusion.

Limitations of the study

A limitation of this study is that we have no record of the parents’ ethnic or socioeconomic background, or no measure of adequacy of samples for donation, and we were therefore unable to draw any conclusions on possible impact of these factors. When comparing different interventions, RCTs are regarded as the golden standard. However, randomisation into 10 s UC clamping for this study was considered unethical since there is evidence that children benefit from prolonged placental transfusion for at least 60 s, and the clinical routine in Sweden is to wait 180 s before UC clamping in normal deliveries. We used the historical cohorts from the RCT in Halmstad, Sweden, as controls in this study. The prospectively recruited cohort (60 s) is from a large birth clinic in Stockholm, Sweden, while the controls are from a smaller town where the participants were recruited 2–5 years earlier. Although the inclusion criteria were the same and pregnant mothers in Sweden follow the same well-controlled antenatal programme and the baseline data showed no significant differences in maternal or infant characteristics, it is difficult to know if the study populations are homogenous. We did not use a non-inferiority approach for this study since we aimed to compare results after 60 s UC clamping with 10 and 180 s. Nor did we perform a power calculation when designing the study, but included an equally large group as the two historical groups. This is a weakness which should be taken into consideration. We have taken measures to avoid systematic biases caused by differences in laboratory routines between the two hospitals by using the same laboratory for analysing the iron status variables as well as CRP.

Collection of UCB for transplantation is a growing and life-saving practice. Tens of thousands UCB units are altruistically donated and stored for public use each year, and as a result newborns are exposed to limited UC clamping time. The idea that UCB left in the placenta after birth is a mere waste that is thrown away if not collected is obsolete. Optimising UC clamping time and investigating the clinical significance to minimise risks for the infant while still enabling collection of UCB for transplantation is a great, but necessary, challenge. A study evaluating volume and in UCB units collected at the Swedish National Umbilical Cord Blood Bank showed that 37% of units collected after 60 s UC clamping met the banking criteria compared with 47% after immediate UC clamping.16 Hence, all the prospective parents considering donating UCB should receive this information.

Conclusion

In this observational study, significantly more children in the 10 s UC clamping group had low iron stores at 4 months compared with children in the 60 and 180 s UC clamping groups. After adjustment for age and sex, there were no statistically significant differences in ferritin concentration between 60 and 180 s UC clamping. Sixty-second UC clamping is therefore preferable to immediate UC clamping. Delaying UC clamping may be more important in boys than in girls to avoid ID in early childhood. Larger studies with long-term follow-up are needed to establish the clinical relevance of different UC clamping strategies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Harjeet Kaur Malhi, Astrid Börjesson, Malin Hjertqvist and Camilla Halzius, the staff at the delivery ward at Karolinska University Hospital Huddinge and all mothers and infants who participated in the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: CG conceptualised and designed the study, analysed data, critically revised and approved the final manuscript as submitted. UA conceptualised and designed the study, carried out all data collection in the prospective cohort, carried out all analyses, drafted the initial manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. OA designed the data collection instruments, contributed to the study design and provided data for the historical cohorts. He also carried out the initial analyses, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. MD, AF, LH-W, MW, KP, IEW and BH participated in the study design, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Funding: The prospective part of the study was supported by The Swedish Childhood Cancer Foundation (grant numbers: PROJ11/043, PROJ12/013); the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research (ALF) at Karolinska Institutet (grant number 20140119) and at Sahlgrenska University Hospital and The Dr Åke Olsson Foundation for Hematological Research, Stockholm. The RCT that provided data for the historical cohorts was supported by Regional Scientific Council of Halland; the HASNA Foundation, Halmstad; HRH Crown Princess Lovisa’s Foundation for Child Care, Stockholm; and the Framework of Positive Scientific Culture, Hospital of Halland, Halmstad.

Disclaimer: The funders were not involved in the study design, data analysis or manuscript preparation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Parental/guardian consent obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the regional ethical review board in Stockholm (2011/2142-31/3) and the RCT was approved by the regional ethical review board at Lund University (41/2008).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no other unpublished data available from this study.

References

- 1.Spencer PM. Controlled cord traction in management of the third stage of labour. Br Med J 1962;1:1728–32. 10.1136/bmj.1.5294.1728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winter C, Macfarlane A, Deneux-Tharaux C, et al. Variations in policies for management of the third stage of labour and the immediate management of postpartum haemorrhage in Europe. BJOG 2007;114:845–54. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01377.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yao AC, Moinian M, Lind J. Distribution of blood between infant and placenta after birth. Lancet 1969;2:871–3. 10.1016/S0140-6736(69)92328-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mercer JS, Erickson-Owens DA. Rethinking placental transfusion and cord clamping issues. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs 2012;26:202–17. 10.1097/JPN.0b013e31825d2d9a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutton EK, Hassan ES. Late vs early clamping of the umbilical cord in full-term neonates: systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. JAMA 2007;297:1241–52. 10.1001/jama.297.11.1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersson O, Hellström-Westas L, Andersson D, et al. Effect of delayed versus early umbilical cord clamping on neonatal outcomes and iron status at 4 months: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2011;343:d7157 10.1136/bmj.d7157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaparro CM, Neufeld LM, Tena Alavez G, et al. Effect of timing of umbilical cord clamping on iron status in Mexican infants: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2006;367:1997–2004. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68889-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonald SJ, Middleton P, Dowswell T, et al. Effect of timing of umbilical cord clamping of term infants on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Evid Based Child Health 2014;9:303–97. 10.1002/ebch.1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oski FA. Iron deficiency in infancy and childhood. N Engl J Med 1993;329:190-3 10.1056/NEJM199307153290308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lozoff B, Beard J, Connor J, et al. Long-lasting neural and behavioral effects of iron deficiency in infancy. Nutr Rev 2006;64(5 Pt 2):34–43. discussion S72-91 10.1301/nr.2006.may.S34-S43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersson O, Lindquist B, Lindgren M, et al. Effect of delayed cord clamping on neurodevelopment at 4 years of age: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169:631–8. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berglund SK, Westrup B, Hägglöf B, et al. Effects of iron supplementation of LBW infants on cognition and behavior at 3 years. Pediatrics 2013;131:47–55. 10.1542/peds.2012-0989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. World Health Organization. Delayed clamping of the umbilical cord to reduce infant anaemia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bone Marrow Donors Worldwide. Secondary bone marrow donors worldwide. 2015. http://www.bmdw.org/

- 15.Brunstein CG, Setubal DC, Wagner JE. Expanding the role of umbilical cord blood transplantation. Br J Haematol 2007;137:20–35. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06521.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frändberg S, Waldner B, Konar J, et al. High quality cord blood banking is feasible with delayed clamping practices. The eight-year experience and current status of the national Swedish Cord Blood Bank. Cell Tissue Bank 2016;17:439–48. 10.1007/s10561-016-9565-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Domellöf M, Dewey KG, Lönnerdal B, et al. The diagnostic criteria for iron deficiency in infants should be reevaluated. J Nutr 2002;132:3680-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saarinen UM, Siimes MA. Developmental changes in serum iron, total iron-binding capacity, and transferrin saturation in infancy. J Pediatr 1977;91:875–7. 10.1016/S0022-3476(77)80880-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Venâncio SI, Levy RB, Saldiva SR, et al. [Effects of delayed cord clamping on hemoglobin and ferritin levels in infants at three months of age]. Cad Saude Publica 2008(Suppl 2):323–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ceriani Cernadas JM, Carroli G, Pellegrini L, et al. [The effect of early and delayed umbilical cord clamping on ferritin levels in term infants at six months of life: a randomized, controlled trial]. Arch Argent Pediatr 2010;108:201–8. 10.1590/S0325-00752010000300005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Georgieff MK. Long-term brain and behavioral consequences of early iron deficiency. Nutr Rev 2011;69(Suppl 1):S43–S48. 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00432.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Domellöf M, Lönnerdal B, Dewey KG, et al. Sex differences in iron status during infancy. Pediatrics 2002;110:545–52. 10.1542/peds.110.3.545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.