Abstract

Introduction

The development and implementation of multisectoral policy to improve health and reduce health inequities has been slow and uneven. Evidence is largely focused on the facts of health inequities rather than understanding the political and policy processes. This 5-year funded programme of research investigates how these processes could function more effectively to improve equitable population health.

Methods and analysis

The programme of work is organised in four work packages using four themes (macroeconomics and infrastructure, land use and urban environments, health systems and racism) related to the structural drivers shaping the distribution of power, money and resources and daily living conditions. Policy case studies will use publicly available documents (policy documents, published evaluations, media coverage) and interviews with informants (policy-makers, former politicians, civil society, private sector) (~25 per case). NVIVO software will be used to analyse the documents to see how ‘social and health equity’ is included and conceptualised. The interview data will include qualitative descriptive and theory-driven critical discourse analysis. Our quantitative methodological work assessing the impact of public policy on health equity is experimental that is in its infancy but promises to provide the type of evidence demanded by policy-makers.

Ethics and dissemination

Our programme is recognising the inherently political nature of the uptake, formulation and implementation of policy. The early stages of our work indicate its feasibility. Our work is aided by a Critical Policy Reference Group. Multiple ethics approvals have been obtained with the foundation approval from the Social and Behavioural Ethics Committee, Flinders University (Project No: 6786).

The theoretical, methodological and policy engagement processes established will provide improved evidence for policy-makers who wish to reduce health inequities and inform a new generation of policy savvy knowledge on social determinants.

Keywords: health inequities, social determinants of health, public policy, qualitative research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Theories from political science are applied at each stage of policy cycle to understand how health equity is affected by policies in a range of government sectors, and policy coherence is studied through systems analysis.

Detailed qualitative data from policy actors improve understanding of dynamics of policy formulation, and implementation processes and innovative methods are used to quantify the impact of policies on health equity outcomes.

Policy-makers are engaged through a Critical Policy Reference Group to increase direct policy relevance of research.

A limited number of sectors are covered in the research programme.

Attribution of change in health and health equity to particular policies remains challenging.

Background

Much progress has been made over the past few decades in understanding the causes of health inequities. Here, we define health inequities to be differences in health risks and outcomes caused by avoidable economic, social and cultural inequalities.1

There is a wealth of empirical evidence showing that inequalities in people’s everyday living conditions in childhood, family life, education, employment, their built environment and healthcare contribute to inequities in physical and mental health outcomes.2–6 Sen’s work highlights that while the material nature of these conditions affect health outcomes, so too does psychosocial disempowerment—the sense of control over one’s life.7 Both the material and psychosocial aspects of people’s daily living conditions are affected by structural inequities,8 which are reproduced through social, cultural and economic processes9 including institutional racism.10–15 These structural factors generate and distribute power, income, goods and services and together with daily living conditions, constitute the social determinants of health inequity.

The use of such evidence to inform effective multisectoral policy development and implementation to improve health and reduce health inequities has been slow and uneven.16 It was very encouraging when ministers and heads of state internationally supported the WHO’s call to action when they endorsed the recommendations of the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health at the 62nd World Health Assembly 2009.17 It is good that national and international health policies increasingly acknowledge the social determinants and point towards the need for action in both health and other policy domains.18–20 The approach of Health in All Policies has been endorsed by the WHO and the European Union and there are now country examples and assessment of implementation.21–24 Within Australia, there is recognition of the importance of health equity in policies although responses tend to be limited.25 There is, however, broad bipartisan commitment to the Close the Gap Strategy designed to reduce the gap between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and other Australians.26 There is increasing recognition that social and health equity is the result of policy interactions in complex systems, where complimentary policy goals and actions across sectors—policy coherence—are vital but challenging to achieve.27 28 This is particularly relevant in the era of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, where many of the 17 sustainable development goals have implications for global health inequities, for example, poverty, promotion of healthy lives, education, gender equality, water and sanitation, economic growth and working conditions.29

Despite these encouraging signs, getting effective action on the daily living conditions that affect health, for example, urban planning, healthcare and quality schooling, remains challenging. Even more difficult is getting action in some of the more politically sensitive issues that challenge the distribution of power, money and resources, for example, trade, taxation, infrastructure and racism.30 Arguably, the lack of effective multisectoral policy and action is because a focus on the social determinants and health equity challenges established political and policy assumptions and current institutional norms and practices. Policy processes reflect the ways in which power is distributed in societies from the initial stages of getting an issue onto the policy agenda, through policy formation, policy implementation and evaluation. The involvement of a wide range of actors including politicians, policy-makers, community and business groups with differing and sometimes conflicting objectives goes to the heart of the raw politics of power.31 The past three decades have seen the ascendancy of neoliberal policies in many countries and the reliance of these policies on a strong ideology of individualism has made focus on broader social determinants more difficult.32 This unsupportive environment is compounded by the complexity and boundary crossing nature of the social determinants of health inequity policy issues, thus making it difficult to allocate responsibility, obtain coherence between policy goals and attribute their contribution to changes in the distribution of health outcomes.

Without being so naive as to think that having the ‘right’ sort of evidence would solve all of these issues, we believe that evidence does matter but that it has to be fit for purpose.33 Arguably, the majority of the evidence base associated with the social determinants is inadequate to help understand and address fast-changing social and economic circumstances.34 Much evidence is largely at the technical level, focused on the facts of health inequities rather than understanding the political and policy processes.35 36 Many of the conditions and processes that make for effective policy and action are poorly understood theoretically and practically, making it very important to produce evidence that is robust and savvy about policy and political processes and realities.

It is these evidence and policy challenges that led us to define the goal of a research programme, the Centre of Research Excellence (CRE) in Social Determinants of Health Equity, funded for 5 years through the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council as ‘to provide evidence on how political and policy processes could function more effectively in order to operationalise the social determinants to achieve better and more equitable health outcomes’. The protocol for the CRE is described in this paper.

The research questions are:

How do different policy actors and institutions shape the ways by which health equity enters or exits the policy agenda?

What is the coherence/incoherence in a complex policy system in terms of pursuit of health equity goals?

What mix of actors, values, institutional practices and systems makes for successful policy implementation that contributes to health equity?

What is the impact of select public policies on the social distribution of health outcomes?

The specific objectives of the research programme are to:

- Extend and develop a programme of research focused on the social determinants of health equity that is designed to:

- advance the understanding of what works to improve health equity;

- increase understanding of the dynamics between policy processes and use of evidence under conditions of multiple policy agendas and power inequities among stakeholders.

Train researchers in the art and science of public policy research for health equity, putting particular emphasis on the translation of the research;

Develop formal processes of knowledge exchange relating to effective action on the social determinants of health equity.

Analytical framework

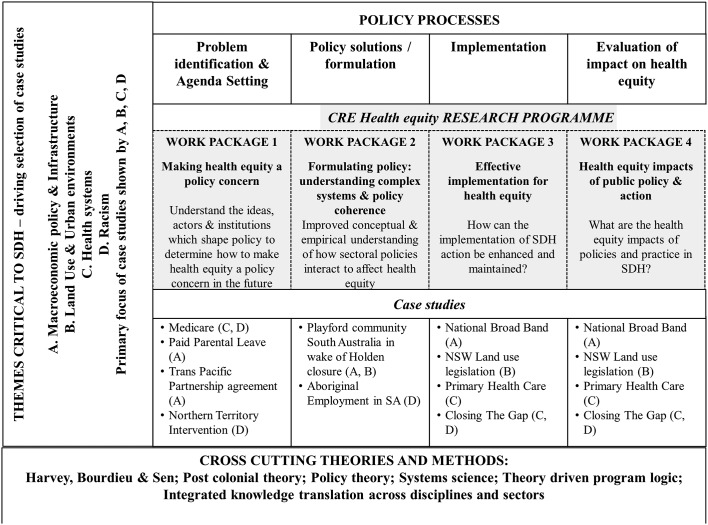

Our overarching analytical framework (figure 1) draws on a plurality of theories and methods from political and social sciences and public health, taking a highly innovative and necessarily conceptually and analytically complex approach. The adoption of this pluralistic theoretical approach is a response to our growing sense that the methodological toolkit traditionally used by public health is limited for these sorts of policy questions and also responds to recent calls for public health to pay more attention to the insights that can be gained from political science in terms of the ways in which policy is enacted and implemented.34 37

Figure 1.

CRE Health Equity research programme framework. CRE, Centre of Research Excellence; NSW, New South Wales; SA, South Australia; SDH, social determinants of health.

Policy theory is central to the work, guiding our exploration of the ways in which issues get on the policy agenda and are acted on,38–40 and the individual, institutional and system capacity required for successful implementation.41 We incorporate sociological analyses of changes in the pace and nature of policy-making, with the 24/7 cycle shifting decision-making away from consultative processes towards structures that favour executive elites.42 The CRE applies the theories of Bourdieu, Harvey and Sen7–9 to understand how inequities in the distribution of structural factors affect individual agency43 and so health, and how empowerment increases the ability of individuals to develop health-promoting capabilities.44 Given that the most glaring health inequity in Australia is that of the 10–11 year life expectancy gap between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians and other Australians,45 we will pay particular attention to ways in which racism affects the ways in which social determinants of health operate in Australian society. Each work programme will give consideration to this topic and the case studies on the Northern Territory Intervention, Primary Healthcare and the Closing the Gap strategy will especially focus on the impact of racism. We will also consider the development and impact of mainstream policies on Indigenous Australians and undertake research on the social determinants of Indigenous health and Indigenous specific policies.46 Indigenous health knowledge is based on collective/holistic principles rather than individual/reductionist principles, and this different theoretical basis will contribute to our understanding of evidence and policy development and implementation.47 One of our particular aims is to work at the ‘Knowledge Interface’47 and integrate indigenous ways of seeing and doing with western scientific ways to understand reasons for policy uptake, formulation and implementation.

Methods

The programme of work is organised around the policy process in four work packages (WP) using four thematic areas (macroeconomics and infrastructure, land use and urban environments, health systems and racism) (figure 1). In the CRE, we cannot study every possible health determinant and consequently have selected four themes, three of which relate to the structural drivers that shape the distribution of power, money and resources, and which affect people’s daily living conditions. The fourth is important because the health of Indigenous peoples highlights an extreme inequity and enables us to examine the intersection of historical and contemporary policies and the ways in which they are underpinned by racism. Our research team consists of 10 chief investigators, 2 of whom (FB and SF) are the codirectors of the centre. Six research staff are employed (equivalent to 5.4 full-time equivalent over the 5 years of the centre). The Centre also has six overseas and four Australian associate investigators. They will be primarily involved in our annual retreat with each committed to visiting at least once. The main policy actor input will be through our Critical Policy Reference Group (CPRG). Using these thematic areas, we will provide evidence on how the policy processes can be navigated more effectively to operationalise action on the social determinants of health equity. Figure 1 shows which case studies are focusing on which thematic area.

Four thematic areas

Macroeconomic and infrastructure policies, including trade and investment, employment and telecommunications, are primary drivers of the distribution of money and other material resources, which have an impact on a range of daily living conditions, such as working conditions and household incomes, access to and uptake of health and social services and availability and affordability of disease risk.14 15 48–51 Macroeconomic and infrastructure policies will be examined in each case study as a determining driver and will be particularly relevant to the Trans-Pacific Partnership Trade Agreement case (WP 1), the closure of the Holden factory (WP 2) and the construction of the National Broadband Telecommunication Network (WP 3). Our work in this theme will be informed by Harvey’s critique of neoliberalism and by Sen in terms of the importance he places on macroeconomic interventions encouraging economic empowerment and psychosocial empowerment. The nature of land use and urban environments in countries around the world has contributed to a growing gap between rich and poor in terms of affordable housing, employment opportunities, transportation, levels of pollution and sanitary conditions.4 52–55 Participation, partnerships and community empowerment are critical elements of good governance for addressing urban health inequities.56 Yet evidence suggests that in urban planning, power is vital in determining whose interests prosper most.55 57 This theme will be developed comprehensively in the urban planning case study in WP3 which will consider a major urban planning system intervention. The work of Harvey on urban planning under neoliberalism will inform this work as will institutional theory. Successive reviews of health systems have recommended a policy shift to primary health care (PHC),58 showing that the development of an effective and strengthened PHC sector promises cost reduction, effective health promotion and disease prevention and much improved management of complex chronic conditions.3 59 Yet this shift fails to happen despite bipartisan support for this policy direction.3 Considerations of health systems will be most evident in the Medicare case in WP 1, in the implementation of recent Australian PHC policy (WP 3) and the health sector aspects of the Closing the Gap strategy (WP 3). Indigenous health is the most glaring health inequity in Australia and other colonised nations. Improving indigenous health has long been recognised as requiring action on a legacy of institutional practices60 especially racism through action on social determinants including increasing self-determination.4 61 Our commitment in the CRE is to develop ways in which we can combine western knowledge systems with Indigenous knowledge systems drawing on the work of indigenous scholars such as Durie.47 We intend that decolonised perspectives will inform each of our cases, and we intend to examine exactly what decolonised methods applied to policy studies look like and the ways in which institutional racism is present in policy design and implementation processes.

Policy Case Studies

Central to our work is policy case studies methodology, which is the preferred strategy ‘when how or why questions are being posed, and when the focus is on a contemporary phenomenon within some real-life context’.62 Our approach draws on realist methodologies63 asking the questions of ‘what works, for whom and in what context?’ and explicitly combines empiricism and theory throughout the research process. This approach is suited to explaining complex policy development and implementation because it reflects the realities of complex non-linear dynamics rather than trying to impose a linear order.64

WP 1 is a retrospective analysis of four policy areas while WPs 2–4 are examining current policy. WPs 1 (agenda setting) and 3 (implementation) use similar methods. Each develops case studies using qualitative methods following Yin.65 A case study is an in-depth study of a single unit, or a group of units, where the researcher’s aim is to elucidate features of a larger class of similar phenomena. Case study designs are recognised in public health social science research as providing important insight where other designs (eg, controlled trials) are not possible.43 The use of multiple case studies offers the ability to understand each policy area in detail and then to compare across the four cases for common themes in the way health equity is dealt with or not.62 Data collection involves the use of publicly available documents (policy documents, published evaluations of policy, parliamentary readings and media coverage) and interviews with key informants (policy-makers, former politicians, civil society and private sector), approximately 25 per case. Data analysis will be mostly conducted with the aid of NVIVO software. Content analysis of documents will focus on how ‘social and health equity’ is included and conceptualised in documents. Analysis of the interview data will include qualitative descriptive analysis which focuses on the data themselves44 and critical discourse analysis which connects the data with theoretically based explanations.45 Our final analysis will combine the assessment of the policy documents and interviews and will be driven by a plurality of theoretical considerations.

In WP 2 (policy design and coherence), an important methodological development being tried is the use of qualitative system science techniques to examine policy coherence as it relates to health inequities, enabling the assessment of interactions between policies and positive and negative feedbacks within complex policy systems. This WP is placed based and the data collection will constitute elements of action research. Data collection will involve a series of workshops with policy actors to map the likely health impact of the Holden closure and policy responses. The findings from these workshops will be reported back to the policy actors (through policy symposia and short reports), and we anticipate they will use them to refine and adjust policy responses. Part of our research will be documenting the extent to which these changes occur.

Our quantitative work on assessing the impact of public policy on health equity outcomes (WP4) is experimental and will advance a methodological area that is in its infancy but aims to provide the type of evidence that is in demand by policy-makers.

Work packages

WP 1: Agenda setting: making health equity a policy concern (years 1–3)

Rationale and purpose

Our starting hypothesis is that health equity is not a central policy priority and often not represented in political values, and if health equity is considered there while social determinants may be recognised policy uses medical or behavioural solutions.66 Therefore, we need research that focuses on (1) understanding how to shift a health equity issue such that it becomes a political and policy priority, (2) identifying the political and institutional barriers to and opportunities for health equity policy development and (3) which social determinants are considered in policy and which are seen as too risky.

We will examine four policy case studies retrospectively. Using policy theories of agenda setting38 67 and political values,68 the aims of WP1 are to identify the power of actors involved with the issue, the power of ideas used to define and describe the issue, the power of political contexts to inhibit or facilitate political support and the power of certain characteristics of the issue which inspire action, culminating in the determination of how health equity was represented in the policy. Two case studies are examples where health equity has been prominent in policy goals (adoption of Medicare Australia’s universal public health insurance, the introduction of Australia’s first Paid Parental Leave policy) and two examples where health equity arguments appear to have had little influence (Northern Territory Intervention, a policy of a conservative Australian government, which responded to a report on child sexual abuse in the Northern Territory; negotiations concerning the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement).

In each case study, we will examine documentary evidence concerning the policy adoption (media analysis, Hansard discussions and issues/green/white papers) and conduct key informant interviews with policy-makers, academics and civil society advocates who were concerned with the policy in the lead up to and the time of its adoption. The aim of the interviews is to elicit contextual data in areas such as institutional memberships and accountability and decision-making systems and authorities to determine who was lobbying for or against the policy and determine their relative power as well as how key policy goals emerge. Interviews will also probe for evidence of the policy frames, arguments and data that may have succeeded in the past in moving towards greater policy coherence and the types of governance structures that might achieve such coherence.

WP 2: Formulating policy: understanding complex systems, policy coherence and health equity (years 1–4)

Rationale and purpose

Policies that emerge from a narrowly focused ‘silo’ approach may work initially to improve health. They are, however, often ineffective (even damaging) in the medium to long term because of their failure to take account of the non-linear effects of cross-sector feedback.69 In the CRE, we will apply system science methods that enable improved understanding of the interactions and positive and negative feedbacks within complex systems and test the approach using real-time policy. This will be done in the context of real-life policy with a focus on South Australia, which is transitioning from a manufacturing-dependent economy to one planned to be based on new industries. The first case study will be in Playford, a council area in the north of Adelaide where the Holden car factory will close in 2017. Holden’s closure is likely to result in job loss and the creation of a pool of workers who have no option but to accept work in low wage, insecure and poor quality jobs.70 The closure of Holden is likely to introduce a range of contradictory and complimentary policies in a community that is already experiencing high levels of social disadvantage (high unemployment, public housing and people receiving welfare benefits). We intend to use the work of Bourdieu71 to examine the ways in which policies are able to interrupt the reproduction of class inequities. We will identify the essential drivers of this system’s behaviour and change. We will use a systems science method72 called Collaborative Conceptual Modelling (CCM), which is designed to support a team’s efforts to improve their understanding of the basic dynamics of their system of interest, thereby improving their adaptive capacity. Via a number of workshops with policy actors and community groups in Playford, we will work to develop a set of simple causal structures capturing important aspects of the feedback dynamics of their system of interest, stressing systems rather than linear thinking. We will then work collaboratively with these local policy actors to determine how they respond to this process and emerging evidence and whether it does or does not lead to any policy or practice change. We anticipate that this ‘real-time’ policy engagement will enable our research findings to inform policy actors and as such represent action research. We will engage with policy-makers through policy fora and feedback sessions. We will monitor the change and adapt the systems analysis as policy develops and draw on Bacchi’s critical approach73 of ‘what’s the problem represented to be’ (WRP) to examine how policies respond to the Holden closure. This WP will also examine the dynamics surrounding Aboriginal employment in South Australia and the extent to which the new employment environment is able to increase the employment of Aboriginal people and will adapt the CCM to map and understand the policy environment and its impacts on health equity.

WP 3: Effective implementation for health equity (years 1–4)

Rationale and purpose

It is well-established in the policy literature that policy as designed is usually very different to policy as implemented, and actors, institutions and system factors account for this gap.74 Implementation research focuses on the question ‘What is happening?’ in the design, implementation, administration, operation, services and outcomes of policy and social programmes; it also asks, ‘Is it what is expected or desired?’ and ‘Why is it happening as it is?’

We hypothesise that policy implementation does not privilege health equity over other goals and is often lost during implementation processes.75 76 To test this, we will assess the implementation of policies in four thematic areas in terms of how actors, institutions, values, systems and other factors influence policy implementation and the extent to which health equity is considered. We will follow policy implementation longitudinally in the four policy case studies: (1) construction and implementation of a national broadband network (telecommunications), (2) land use planning and its impact on housing and spatial equity, (3) primary healthcare policy, (4) closing the gap—a bipartisan supported policy to reduce the gap in life expectancy between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. Each of these cases will be examined in terms of the broader Australian policy context which is dominated by neoliberalism77 and the extent to which the policies do or do not encourage collective and individual empowerment.7

WP 4: Health equity impacts of public policy (years 2–5)

Rationale and purpose

There is very little research that assesses the effectiveness of public policy as a tool for building equitable population health. Thus, there is a need for the development and application of innovative methods to evaluate the health equity impact of both sectoral specific and integrated action on health equity. When we are in discussion with policy actors, the demand for this type of evidence is high.

Assessing and measuring the health equity impact of policies is methodologically challenging because it is rarely possible to have a control community in which the policy is not implemented and so attribution of change to a particular policy is very hard. Consequently, this WP will focus on testing the feasibility of a framework and methodologies nested within this framework. By combining different approaches for example, natural policy experiments, equity-focused health impact assessment and systems modelling, we hypothesise that it will be possible to measure the health equity impacts of public policies.

Within the framework, we will develop policy logic models (PLMs) for each policy case in WP3. These PLMs will examine the mechanisms that are responsible for policy change by articulating and testing the links between policies and the changes they aim to bring about. To do this, we will identify (1) the policy drivers which will impact on equity; (2) the policy procedures which will impact on equity; (3) indicators for outcomes which best represent the equity effects (both positive and negative) of these policy drivers and procedures; (4) the methods to measure these effects quantitatively and qualitatively and (5) the mechanisms by which policy drivers and procedures have produced changes in outcomes. The methodological challenge here is to be able to estimate health equity impacts when the policy interventions occur within complex interacting systems.

Supplementary ethics approval has been given by other participating universities and Aboriginal health ethics committees in regions where the research is being conducted.

Engagement with policy actors

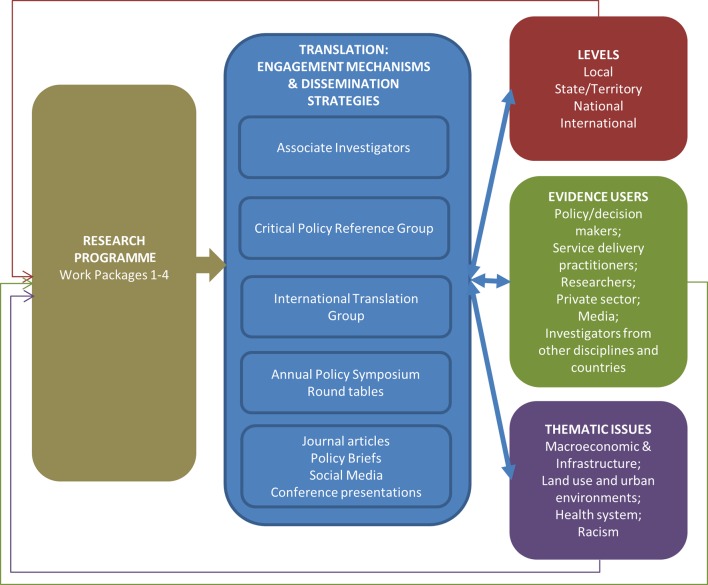

The aim of the CRE is to ensure that the policy learnings are developed in consultation with the policy community and then disseminated widely to maximise influence of research on policies relating to health equity. This will be done through integrated knowledge translation, which by definition engages potential end users in the policy community as partners in all aspects of the research process in a collaborative approach to research.78 We conceptualise the policy community as consisting of multiple actors including current and future politicians, federal, state and local government public servants, front-line bureaucrats and non-government organisations (NGOs), civil society groups, researchers, private sector, media and investigators from different disciplines and countries. Members of the policy community are fully integrated into the four work packages and through our engagement mechanisms and dissemination strategies, each of which is summarised in figure 2. Our engagement mechanisms are at difference scales (local, state/territory, national and international) and reflect our four thematic areas. The work of the CRE is guided by a CPRG, which provides a litmus test of the policy relevance of the research and helps enable real-time translation of the research into policy and practice. All members of this group have been selected because of their practical experience of policy processes in relation to the determinants of health equity. Most members are either senior public sector executives or senior executives of NGOs including the Lowitja Institute in recognition of the importance of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health to the research. The chair of this group will be invited to the research team retreats and the CPRG comments on the policy relevance of the research. Four meetings of the group will be held annually including one face-to-face meeting. Policy Days will be planned in conjunction with our CPRG and a range of policy actors invited. The Policy Days will facilitate dissemination of the CRE methods and evidence and bring the policy community together to accelerate learning across government and horizontally between peers. Our findings will inform a media strategy designed to increase understanding of the importance of social determinants in reducing health equity. We will work closely with a highly skilled health journalist who has agreed to consult to the CRE on effective social media use. The CRE’s key research findings will be reported in policy briefings as well as standard academic outputs. The briefs will be targeted by sector and level of government and made available online and also through targeted distribution to key policy-makers.

Figure 2.

Centre of Research Excellence Health Equity Translation: engagement mechanism and dissemination strategies.

Discussion

The work of the CRE is taking research on the social determinants of health equity to a new level by recognising the inherently political nature of the uptake, formulation and implementation of policy. Our work programme is in its early stages and is proving the feasibility of the approach. Issues that have presented themselves in our initial stages concerning gaining access to some high-level policy actors, a rapidly changing policy environment in which planned policies do not proceed as initially envisaged (for example, although signed by countries, the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement has an uncertain future) and the politically sensitive nature of any critique of current policy. Despite such challenges, our early work in the CRE is proceeding well. Detailed reviews of the literature have confirmed the near silence on understanding the complex political processes that underpin policies on social determinants. Our initial work on policy coherence using CCM has been met with enthusiasm from policy-makers who spontaneously comment on the value of seeing the policy environment mapped out and the ways in which changes to employment impact on health in so many diverse ways. Progress has also been made in integrating Indigenous and western knowledges and is informing our interviewing techniques, coding and interpretation. The CPRG is confirming that the knowledge we will be producing is of the kind they believe will influence policy because it shows acknowledgement of the political nature of the decisions and processes behind policy.

The research programme we have designed will give rise to challenges. Methodologically, we may have problems in recruiting elite groups as research informants. While we have done this successfully in previous research (for example with former health ministers in79), such recruitment can be difficult when the policy story we are researching is not a positive one as will be the case for some of our case studies. We also acknowledge that the aim of WP 4 to document health impacts of policy interventions in complex systems will stretch existing methodological knowledge and rely on us to develop novel approaches. Theoretically, we recognise that policy implementation literature is in its infancy and gives us little guidance so to a large extent we will be making new ground through our research programme. Finally, in terms of uptake of our findings, we recognise that this will only happen in political and policy environments that are receptive to the idea of equity. The existence of such environments is out of our control.

Despite these challenges, we anticipate that the theoretical, methodological and policy engagement processes we have established will bear fruits over the coming years and provide improved evidence for policy-makers who wish to reduce health inequities within their jurisdiction. Our work will also inform a new generation of policy savvy research and researchers on action on social determinants.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval has been secured from each institutional ethics committee. Ethics was approved by the Flinders University Social and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee 2015/6786 and the Australian National University Human Ethics Protocol 2015/243. Ethics approval has also been sought from relevant Aboriginal ethics authorities in relation to national and community-based research. Given our focus on understanding and engaging with Indigenous knowledges, we are particularly keen to ensure our research processes are not reflective of the colonised society in which the research is conducted and wherever possible apply a decolonised, reflexive practice. We are also conscious that as parts of our research plan is dealing with real-time policies, we have to be mindful that our analyses will not always sit well with policy actors. Our intention is to report our analysis as accurately as possible without filtering it for political acceptability.

Our dissemination plan includes the follow: (1) publications in Australian and international peer-reviewed journals; (2) presentation at public health and political science national and international conferences; (3) policy briefings for policy actors; (4) community reports and interactive feedback session and (5) policy symposia, which will be designed to encourage debate about the policy implications of our research. The research data will be stored securely on password-protected databases. On conclusion of the research deidentified data will be lodged in the Australian Data Archive social science database after gaining the permission of our research partners.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of our fellow chief investigators (Adrian Kay, Dennis McDermott, Ron Labonte, Anna Ziersch, Lyndall Strazdins, Patrick Harris, Tamara Mackean) and researcher Dr Matt Fisher to the development of the CRE approach.

Footnotes

Contributors: The article was drafted by the two authors based on a research proposal prepared by them. Both contributed to critical review of the article and approved the final version.

Funding: This study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (AP1078046).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Umbrella ethics approval have been obtained from the Social and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee, Flinders University (Project No: 6786).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Int J Health Serv 1992;22:429–45. 10.2190/986L-LHQ6-2VTE-YRRN [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strazdins L, Shipley M, Clements M, et al. . Job quality and inequality: parents’ jobs and children’s emotional and behavioural difficulties. Soc Sci Med 2010;70:2052–60. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baum FE, Legge DG, Freeman T, et al. . The potential for multi-disciplinary primary health care services to take action on the social determinants of health: actions and constraints. BMC Public Health 2013;13:460 10.1186/1471-2458-13-460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baum F, Putland C, MacDougall C, et al. . Differing levels of social capital and mental health in suburban communities in australia: did social planning contribute to the difference? Urban Policy and Research 2011;29:37–57. 10.1080/08111146.2010.542607 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friel S. Global Research Network on Urban Health Equity Members. Improving urban health equity through action on the social and environmental determinants of health: final report of the GRNUHE. London: University College London, Rockefeller Foundation, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dwyer J, Kelly J, Willis E, et al. . Managing two worlds together (Reports 1-4). Melbourne: The Lowitja Institute, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sen A. Development as freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harvey D. The enigma of capitalism. New York: Oxford Univeristy Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bourdieu P. The forms of capital : Richardson J, Handbook of theory and research for sociology of education. New York: Greenwood Press, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henry BR, Houston S, Mooney GH. Institutional racism in Australian healthcare: a plea for decency. Med J Aust 2004;180:517–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paradies Y. A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:888–901. 10.1093/ije/dyl056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Labonté R, Mohindra K, Schrecker T. The growing impact of globalization for health and public health practice. Annu Rev Public Health 2011;32:263–83. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ziersch A, Gallaher G, Baum F, et al. . Racism, social resources and mental health for Aboriginal people living in Adelaide. Aust N Z J Public Health 2011;35:231–7. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2011.00681.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friel S, Hattersley L, Snowdon W, et al. . Monitoring the impacts of trade agreements on food environments. Obes Rev 2013;14:120–34. 10.1111/obr.12081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Souza RM, Strazdins L, Lim LL, et al. . Work and health in a contemporary society: demands, control, and insecurity. J Epidemiol Community Health 2003;57:849–54. 10.1136/jech.57.11.849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Leeuw E. Engagement of sectors other than health in integrated health governance, policy, and action. Annu Rev Public Health 2017;38:329–49. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sixty-Second World Health Assembly. Reducing health inequities through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Assembly; 2009, Report No: WHA62.14. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Health Do. : Health DO, Victorian public health and wellbeing plan 2011-2015: Victorian Government, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Health S. : Australia GOS, Health in all policies: The South Australian approach: Adelaide, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Services DoHaH. : Government TS, Tasmania’s health planning framework: Hobart, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leppo K, Ollila E, Peña S, et al. : Health M, Health in All Policies: Seizing opportunities, implementing policies. Helsinki, Finland, 2013:25–42. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delany T, Lawless A, Baum F, et al. . Health in all policies in South Australia: what has supported early implementation? Health Promot Int 2016;31:dav084–98. 10.1093/heapro/dav084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molnar A, Renahy E, O’Campo P, et al. . Using win-win strategies to implement health in all policies: a cross-case analysis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0147003 10.1371/journal.pone.0147003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baum F, Lawless A, MacDougall C, et al. . New norms new policies: did the adelaide thinkers in residence scheme encourage new thinking about promoting well-being and health in all policies? Soc Sci Med 2015;147:1–9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher M, BAUM FE, MacDougall C, et al. . To what extent do Australian health policy documents address social determinants of health and health equity? J Soc Policy 2016;45:545–64. 10.1017/S0047279415000756 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Council of Australian Governments. COAG National Indigenous Reform Agreement (closing the gap). Canberra: Common wealth of Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.May PJ, Sapotichne J, Workman S. Policy coherence and policy domains. Policy Studies Journal 2006;34:381–403. 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2006.00178.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Signal LN, Walton MD, Ni Mhurchu C, et al. . Tackling ‘wicked’ health promotion problems: a New Zealand case study. Health Promot Int 2013;28:84–94. 10.1093/heapro/das006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sachs JD. From millennium development goals to sustainable development goals. The Lancet 2012;379:2206–11. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60685-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shankardass K, Solar O, Murphy K, et al. . A scoping review of intersectoral action for health equity involving governments. Int J Public Health 2012;57:25–33. 10.1007/s00038-011-0302-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raphael D. Beyond policy analysis: the raw politics behind opposition to healthy public policy. Health Promot Int 2015;30:380–96. 10.1093/heapro/dau044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baum F, Fisher M. Why behavioural health promotion endures despite its failure to reduce health inequities. Sociol Health Illn 2014;36:213–25. 10.1111/1467-9566.12112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelly MP, Morgan A, Bonnefoy J. 2007. The social determinants of health: developing anevidence base for political action. Geneva: World Health Organization Commission on the Social Determinants of Health from the Measurement and Evidence Knowledge Network. [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Leeuw E, Clavier C, Breton E. Health policy—why research it and how: health political science. Health Res Policy Syst 2014;12:55 10.1186/1478-4505-12-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Catford J. Advancing the ‘science of delivery’ of health promotion: not just the ‘science of discovery’. Health Promot Int 2009;24:1–5. 10.1093/heapro/dap003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friedman EA, Gostin LO. From local adaptation to activism and global solidarity: framing a research and innovation agenda towards true health equity. Int J Equity Health 2017;16:1–4. 10.1186/s12939-016-0492-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kickbusch I. Addressing the interface of the political and commercial determinants of health. Health Promot Int 2012;27:427–8. 10.1093/heapro/das057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kingdon J. Agendas, alternatives and public policies. 2nd edn New York: Addison-Wesley Educational Publishers, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dowding K, Faulkner N, Hindmoor A, et al. . Change and continuity in the ideology of Australian prime ministers. Aust J Polit Sci 2012;47:455–72. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baumgartner FR, Green-Pedersen C, Jones BD. Comparative studies of policy agendas. J Eur Public Policy 2006;13:959–74. 10.1080/13501760600923805 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bowen S, Zwi AB. Pathways to "evidence-informed" policy and practice: a framework for action. PLoS Med 2005;2:e166 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheuerman WE. Liberal democracy and the social acceleration of time. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Browne-Yung K, Ziersch A, Baum F. ‘Faking til you make it’: social capital accumulation of individuals on low incomes living in contrasting socio-economic neighbourhoods and its implications for health and wellbeing. Soc Sci Med 2013;85:9–17. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Labonte R, Woodard GB, Chad K, et al. . Community capacity building: a parallel track for health promotion programs. Can J Public Health 2002;93:181–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Welfare AIoHa. Australia’s health 2016. Canberra: AIHW, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Osborne K, Baum F, Brown L. What works? A review of actions addressing the social and economic determinants of Indigenous health. Canberra: Australian Government Closing the Gap Clearinghouse, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Durie M. Indigenous knowledge within a global knowledge system. Higher Education Policy 2005;18:301–12. 10.1057/palgrave.hep.8300092 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Friel S, Gleeson D, Thow AM, et al. . A new generation of trade policy: potential risks to diet-related health from the trans pacific partnership agreement. Global Health 2013;9:46 10.1186/1744-8603-9-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strazdins L, Shipley M, Clements M, et al. . Job quality and inequality: parents’ jobs and children’s emotional and behavioural difficulties. Soc Sci Med 2010;70:2052–60. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Newman LA, Biedrzycki K, Baum F. Digital technology access and use among socially and economically disadvantaged groups in South Australia. J Community Informat 2010;6 http://ci-journal.net/index.php/ciej/article/view/639/582 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Newman L, Biedrzycki K, Baum F. Digital technology use among disadvantaged Australians: implications for equitable consumer participation in digitally-mediated communication and information exchange with health services. Aust Health Rev 2012;36:125–9. 10.1071/AH11042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Friel S, Akerman M, Hancock T, et al. . Addressing the social and environmental determinants of urban health equity: evidence for action and a research agenda. J Urban Health 2011;88:860–74. 10.1007/s11524-011-9606-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harris P, Haigh F, Sainsbury P, et al. . Influencing land use planning: making the most of opportunities to work upstream. Aust N Z J Public Health 2012;36:5–7. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2012.00822.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.DoIa T. Our cities: the challenge of change. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harris P, Kent J, Sainsbury P, et al. . Framing health for land-use planning legislation: a qualitative descriptive content analysis. Soc Sci Med 2016;148:42–51. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barten F, Akerman M, Becker D, et al. . Rights, knowledge, and governance for improved health equity in urban settings. J Urban Health 2011;88:896–905. 10.1007/s11524-011-9608-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Castells M. The urban question. London: Edward Arnold, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Commission NHaHR. A healthier future for all Australians: final report. Canberra: Australian Government, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mackean T, Adams M, Goold S, et al. . Partnerships in action: addressing the health challenge for aboriginal and torres strait islander peoples. Med J Aust 2008;188:554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Commission HRaEO. Bringing them home: findings of the national inquiry into the separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families. Sydney: HREOC, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tynan M. Anthropology, community development, and public policy: the case of the kaiela planning council. Collab Anthropol 2013;6:307–33. 10.1353/cla.2013.0009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods. 4th edn London: Sage Publications, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pawson RT, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation. London: Sage Publications, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Patton MQ. Developmental evaluation: applying complexity concepts to enhance innovation and use. New york: Guilford Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods. 5th edn Thousand Oaks: SAGE, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baum F, Fisher M. Are the national preventive health initiatives likely to reduce health inequities? Aust J Prim Health 2011;17:320–6. 10.1071/PY11041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sabatier PA. Public policy: toward better theories of the policy process. : Crotty WJ, Political science: looking to the future. Evanston: Northwest University Press, 1991:265–92. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stewart J. Public policy values. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Proust K, Newell B, Brown H, et al. . Human health and climate change: leverage points for adaptation in urban environments. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2012;9:2134–58. 10.3390/ijerph9062134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Anaf J, Newman L, Baum F, et al. . Policy environments and job loss: lived experience of retrenched Australian automotive workers. Crit Soc Policy 2013;33:325–47. 10.1177/0261018312457858 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bourdieu P. The weight of the world: social suffering in contemporary society. Cambridge: UK: Cambridge Policy Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Newell B, Proust K. Introduction to collaborative conceptual modelling. Canberra: Australian National University Repository, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bacchi C. Analysing policy: what’s the problem represented to be?. Frenchs Forest: NSW: Pearson Education, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Howlett M, Ramesh M, Perl A. Studying public policy: policy cycles and policy subsystems. 3rd edn Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Labont R, Pooyak S, Baum F, et al. . Implementation, effectiveness and political context of comprehensive primary health care: preliminary findings of a global literature review. Aust J Prim Health 2013;14:58–67. 10.1071/PY08037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Peters DH, Tran N, Adam T. Implementation research in health: a practical guide. Geneva: Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, WHO, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Miller C, Orchard L, Australian Public Policy: progressive ideas in the Neo-Liberal Ascendency. Bristol: Policy Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Denis JL, Lomas J. Convergent evolution: the academic and policy roots of collaborative research. J Health Serv Res Policy 2003;8(Suppl 2):1–6. 10.1258/135581903322405108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Baum FE, Laris P, Fisher M, et al. . "Never mind the logic, give me the numbers": former Australian health ministers’ perspectives on the social determinants of health. Soc Sci Med 2013;87:138–46. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.