Abstract

Objectives

Fatal drowning estimates using a single underlying cause of death (UCoD) may under-represent the number of drowning deaths. This study explores how data vary by International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 coding combinations and the use of multiple underlying causes of death using a national register of drowning deaths.

Design

An analysis of ICD-10 external cause codes of unintentional drowning deaths for the period 2007–2011 as extracted from an Australian total population unintentional drowning database developed by Royal Life Saving Society—Australia (the Database). The study analysed results against three reporting methodologies: primary drowning codes (W65-74), drowning-related codes, plus cases where drowning was identified but not the UCoD.

Setting

Australia, 2007–2011.

Participants

Unintentional fatal drowning cases.

Results

The Database recorded 1428 drowning deaths. 866 (60.6%) had an UCoD of W65-74 (accidental drowning), 249 (17.2%) cases had an UCoD of either T75.1 (0.2%), V90 (5.5%), V92 (3.5%), X38 (2.4%) or Y21 (5.9%) and 53 (3.7%) lacked ICD coding. Children (aged 0–17 years) were closely aligned (73.9%); however, watercraft (29.2%) and non-aquatic transport (13.0%) were not. When the UCoD and all subsequent causes are used, 67.2% of cases include W65-74 codes. 91.6% of all cases had a drowning code (T75.1, V90, V92, W65-74, X38 and Y21) at any level.

Conclusion

Defining drowning with the codes W65-74 and using only the UCoD captures 61% of all drowning deaths in Australia. This is unevenly distributed with adults, watercraft and non-aquatic transport-related drowning deaths under-represented. Using a wider inclusion of ICD codes, which are drowning-related and multiple causes of death minimises this under-representation. A narrow approach to counting drowning deaths will negatively impact the design of policy, advocacy and programme planning for prevention.

Keywords: epidemiology, public health, drowning, global burden of disease, international classification of diseases (ICD), methodology, injury

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first total population study in Australia to examine fatal drowning counts via International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 classifications using single and multiple underlying causes of death.

Three different reporting methodologies were used to describe unintentional fatal drowning compared with the total number of cases.

The study provides a greater depth of understanding on how the grouping of ICD-10 codes and the number of included underlying causes of death can impact the fatal drowning count.

Variation due to time taken to close coronial cases at a state and territory level and reporting of official cause of death statistics may impact data quality.

These findings represent Australia and further work in other countries is required.

Introduction

Drowning is a leading cause of unintentional injury-related death,1 2 with children3–6 and low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) disproportionately affected.2 The epidemiology of fatal drowning7 and risk factors leading to drowning are becoming increasingly understood,8–10 subject to the availability of appropriate data.2 11 12

The coding framework most frequently used internationally to describe deaths is the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). Global estimates and many studies rely on one level of cause of death, the underlying cause of death (UCoD), to classify a fatality. The medical certificate cause of death, recommended by WHO for international use, was designed to facilitate the selection of the UCoD. When more than one condition is entered on the death certificate, the underlying cause is selected using the coding rules of the relevant version of the ICD.13 Limitations around ICD codes14 15 include fidelity, accuracy of coding (including injury cause), location11 15 and activity information.15–17 Reporting of statistics using ICD coding has been found to underestimate disease and injury causes including sports and leisure activity-related hospitalisations,18 obesity in hospitalised children19 and drowning deaths,20 distorting resource allocation for prevention.

There are various approaches to identifying and counting drowning deaths.21–23 The use of specific ICD codes is a common strategy, which avoids double counting deaths but misses those with multiple causes. The 2014 Global Report on Drowning2 used only one ICD code per fatality, impacting on the reporting of the worldwide burden, currently estimated at 372 441 unintentional drowning deaths (ICD codes W65-74) annually.

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) uses a similar approach, estimating burden based on one cause of death.24 The most recently published GBD-injury study reports that drowning decreased worldwide by 27% from 1990 to 2013.1 Deciding which ICD codes are included in these calculations and which is used as the primary code can impact the estimated number of deaths. In Australia, multiple cause of death codes are available,25 providing opportunities to fully capture the incidence of fatal drowning.

In Australia, official statistics on cause of death are provided by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS).25 Data are derived from death certificates, which are then assigned ICD codes. To provide evidence for drowning prevention interventions, Royal Life Saving Society—Australia maintains a National Fatal Drowning Database (the Database). The Database is used to describe fatal unintentional drowning in Australia.22 26–30

This study aims to use the Database to describe the coverage of ICD-10 classification of drowning (W65-74). This will include exploring the UCoD, subsequent levels and additional drowning-related ICD-10 codes (T75.1, V90, V92, X38 and Y21).

Methods

In Australia, all sudden and unexpected deaths are investigated by a coroner to determine the circumstances and cause of death.31 All cases are recorded on the National Coronial Information System (NCIS), which is the primary source of information for the Database. In addition to the NCIS, the Database uses triangulation of data via year-round monitoring of: media, police reports, Child Death Review Team reports, social media and reports from life-saving clubs.32 All deaths where unintentional drowning was the primary or contributory cause of death are included in the Database.

The period 1 January 2007 to 31 December 2011 was extracted from the Database. This period was chosen to maximise the proportion of closed cases and those with ICD coding. Cases with a coronial finding of undetermined as to the victim’s intent were included. Intentional cases (suicide, homicide, assault and infanticide) were excluded. Both open (still under investigation) and closed coronial cases were included. At the time of analysis, 94.2% of cases were closed. ICD coding was not provided in 3.7% of cases. Data are correct as at 31 December 2016.

Information contained within the database is a mix of coding extracted from the NCIS and coding developed to describe drowning cases. For the activity, a range of codes are used, including bathing, falls, non-aquatic transport, swimming/recreating and watercraft. The activity code of ‘non-aquatic transport’ covers drowning deaths as a result of vehicles not intended to be used in the water, such as motor vehicles.33

ICD-1034 codes for drowning cases in the NCIS are drawn from the ABS.25 Cases are matched to the NCIS by the ABS and ICD codes provided.32 There are instances where an NCIS case does not have ICD-10 coding, generally due to the inability to match the cases between the NCIS and ABS.35 The proportion of NCIS cases with ICD coding varies by state and territory, from a low of 85% to a high of 99%.36

A maximum of 10 causes of death are able to be categorised within the NCIS. This information includes: the UCoD, which is defined as the initiating cause or event which lead to death.37 Subsequent (multiple) causes are all other conditions, diseases, injuries or events detailed in the death certificate and are coded in sequence.38

Information on sex, age, cause of death, location of drowning, activity immediately prior to drowning, state or territory of drowning location, the resident status of the person who drowned and ICD-10 coding were extracted from the NCIS and entered into the Database in IBM SPSS Statistics V.20.39 SPSS was used to perform χ2 analysis. A modified Bonferonni correction as suggested by Keppel40 was used. Case counts of three or fewer are not presented as per the ethical requirements.

Hereafter, W65-74 are referred to as primary drowning codes and T75.1, V90, V92, X38 and Y21 are referred to as drowning-related codes.

This study analyses incidents where the relevant codes appear as the UCoD or any of the multiple causes. Three new variables were created to categorise cases with:

UCoD W65-74;

UCoD T75.1, V90, V92, X38 or Y21;

T75.1, W65-74, V90, 92, X38 or Y21 as a multiple cause of death (table 1).

Table 1.

ICD-10 drowning codes and other relevant codes (n=1375)

| As referred to within this study | ICD-10 code | Definition | Number of cases as the UCoD (n) |

| Primary drowning codes (W65-74 Accidental drowning and submersion) |

W65 | Drowning and submersion while in bathtub | 40 |

| W66 | Drowning and submersion following fall into bathtub | 9 | |

| W67 | Drowning and submersion while in swimming pool | 94 | |

| W68 | Drowning and submersion following fall into swimming pool | 62 | |

| W69 | Drowning and submersion while in natural water | 384 | |

| W70 | Drowning and submersion following fall into natural water | 156 | |

| W73 | Other specified drowning and submersion | 45 | |

| W74 | Unspecified drowning and submersion | 76 | |

| Drowning-related codes | T75.1 | Drowning and non-fatal submersion | 3 |

| V90 | Drowning and submersion due to accident to watercraft | 78 | |

| V92 | Drowning and submersion due to accident on board watercraft, without accident to watercraft | 50 | |

| X38 | Victim of flood | 34 | |

| Y21 | Drowning and submersion, undetermined intent | 84 | |

| Intentional drowning code | X71 | Intentional self-harm by drowning and submersion | 19 |

| X92 | Assault by drowning and submersion | 0 | |

| Examples of non-drowning codes | G40 | Epilepsy | 40 |

| I25 | Chronic ischaemic heart disease | 23 | |

| R99 | Ill-defined and unknown cause of mortality | 15 | |

| Total | 1212 | ||

ICD, International Classification of Diseases; UCoD, underlying cause of death.

The presence of other ICD-10 codes as UCoD are also examined. T75.1 (a diagnostic code, rather than an external cause code) was included to assess potential under-representation of drowning, consistent with the study by Passmore et al.41

Results

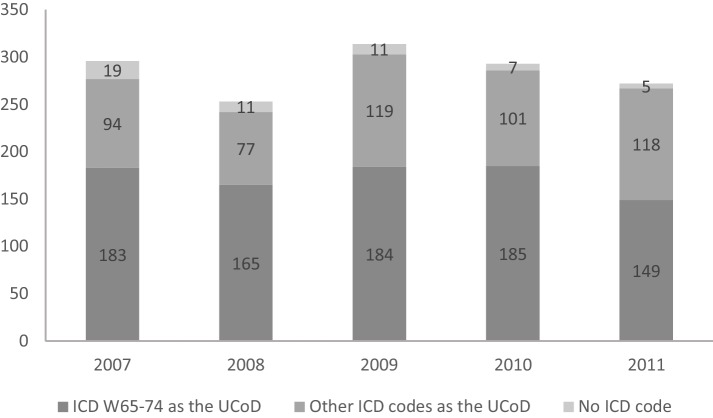

There were 1428 unintentional drowning deaths in Australia (2007–2011). Of these, 83 cases (5.8%) were open and, of these, 53 (3.7%) had no ICD coding (figure 1). The proportion of cases with W65-74 coding (60.6%) ranged from a low of 54.8% in 2011 to a high of 65.2% in 2008. The proportion of cases missing ICD coding decreased over time, from 6.4% in 2007, to 1.8% in 2011 (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of unintentional fatal drowning cases, Australia, 2007–2011 (n=1428). *A given case may have multiple codes and as such this column of the flow chart will not sum to 100.0%.

Figure 2.

Trends over time in unintentional fatal drowning by International Classification of Diseases (ICD) W65-74 code as the underlying cause of death (UCoD), other ICD codes as the UCoD and cases with no ICD codes by calendar year, 2007–2011, Australia (n=1428).

From the Database, 866 cases (60.6%) had an ICD code of W65-74 as the UCoD (figure 2). Drowning of children aged 0–17 years (χ2=34.47; P<0.001), drowning incidents which occurred at the beach (χ2=40.01; P<0.001); on rocks (χ2=25.48; P<0.001); in swimming pools (χ2=19.491; P<0.001); while diving (χ2=16.26; P<0.001); due to falls into water (χ2=56.43; P<0.001); while rock fishing (χ2=18.58; P<0.001) and while swimming and recreating (χ2=75.61; P<0.001) were significantly more likely to have a primary drowning code as the UCoD (table 2).

Table 2.

RLSSA Database drowning cases compared with drowning cases with ICD-10 codes W65-74 as UCoD only by sex, age group, state or territory of drowning incident, category of aquatic location of drowning incident, activity immediately prior to drowning (n=1428)

| RLSSA Database drowning cases | ICD-10 codes W65-74 as UCoD only | % difference | χ2 comparing all drowning deaths to the subsample of W65-74 as UCoD only (P value)* | |

| Total | 1428 | 866 | 39.4 | – |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1098 | 669 | 39.1 | 0.12 (P=0.73) |

| Female | 330 | 197 | 40.3 | |

| Age group (years) | ||||

| 0–17 | 268 | 198 | 26.1 | 34.47 (P<0.001) |

| 18–54 | 709 | 401 | 43.4 | 12.03 (P=0.001) |

| 55+ | 451 | 267 | 40.8 | 1.29 (P=0.26) |

| Resident status of drowning victim | ||||

| Australian | 1343 | 809 | 39.8 | 3.60 (P=0.06) |

| Overseas | 63 | 44 | 30.2 | |

| Unknown | 22 | 13 | 40.9 | – |

| State or territory of drowning incident | ||||

| ACT | 8 | 5 | 37.5 | 0.00 (P=0.98) |

| NSW | 532 | 312 | 41.4 | 2.03 (P=0.15) |

| NT | 43 | 28 | 34.9 | 0.25 (P=0.62) |

| QLD | 360 | 207 | 42.5 | 0.36 (P=0.55) |

| SA | 72 | 49 | 31.9 | 2.01 (P=0.16) |

| TAS | 62 | 38 | 38.7 | 0.01 (P=0.91) |

| VIC | 184 | 103 | 44.0 | 2.00 (P=0.16) |

| WA | 167 | 124 | 25.7 | 10.36 (P=0.001) |

| Category of aquatic location of drowning incident | ||||

| Bathtub/spa bath | 97 | 56 | 42.3 | 0.33 (P=0.57) |

| Beach | 214 | 173 | 19.2 | 40.01 (P<0.001) |

| Lake/dam/lagoon | 122 | 71 | 41.8 | 0.29 (P=0.59) |

| Ocean/harbour | 228 | 91 | 60.1 | 46.64 (P<0.001) |

| River/creek/stream | 406 | 206 | 49.3 | 28.66 (P<0.001) |

| Rocks | 77 | 67 | 13.0 | 25.48 (P<0.001) |

| Swimming pool | 222 | 161 | 27.5 | 19.91 (P<0.001) |

| Other/unknown | 62 | 41 | 33.9 | 0.77 (P=0.38) |

| Activity prior to drowning | ||||

| Bathing | 98 | 56 | 42.9 | 0.50 (P=0.48) |

| Diving | 69 | 57 | 17.4 | 16.26 (P<0.001) |

| Falls | 292 | 227 | 22.3 | 56.43 (P<0.001) |

| Non-aquatic transport | 115 | 15 | 87.0 | 128.61 (P<0.001) |

| Rock fishing | 56 | 49 | 12.5 | 18.58 (P<0.001) |

| Swimming and recreating | 304 | 249 | 18.1 | 75.61 (P<0.001) |

| Watercraft | 216 | 63 | 70.8 | 109.09 (P<0.001) |

| Other | 133 | 88 | 33.8 | 1.09 (P=0.30) |

| Unknown | 145 | 62 | 57.2 | 26.37 (P<0.001) |

Those cases with unknown ICD coding are included in the RLSSA column only.

*Calculated based on the ICD-10 codes W65-74 as UCoD only yes/no variable.

ICD, International Classification of Diseases; RLSSA, Royal Life Saving Society - Australia; UCoD, underlying cause of death.

Adults aged 18–54 years (χ2=12.03; P=0.001), drowning incidents in ocean/harbour locations (χ2=46.64; P<0.001); river/creek/stream locations (χ2=28.66; P<0.001) and drowning incidents as a result of non-aquatic transport incidents (χ2=128.61; P<0.001) and watercraft incidents (χ2=109.09; P<0.001) were significantly less likely to record primary drowning codes (W65-74) as the UCoD (table 2).

The use of W65-74 as the UCoD only, under-reports drowning incidents at ocean/harbour and river/creek/stream locations by 60.1% and 49.3%, respectively compared with the Database. Similarly, drowning deaths as a result of watercraft and non-aquatic transport incidents are under-represented by 70.8% and 87.0%, respectively (table 2).

Where ICD coding was present

Of the 1375 cases with ICD coding, 246 (18.1%) recorded additional drowning codes (T75.1, V90, V92, X38, Y21) as the UCoD. Of these, Y21 and V90 accounted for 5.9% and 5.5%, respectively (figure 2). Drowning deaths at ocean/harbour locations and due to watercraft incidents recorded the highest proportion of additional drowning codes as the UCoD at 43.3% and 61.2%, respectively.

Almost one-fifth of all 1428 drowning cases identified (263; 18.4%) recorded non-drowning codes as the UCoD. Cases with a higher proportion of non-drowning codes as the UCoD were drowning deaths as a result of non-aquatic transport (70.5% other non-drowning codes as the UCoD), drowning deaths as a result of bathing (35.1%) and drowning deaths which occurred in bathtub/spa baths (34.4%).

Of those with ICD coding, common non-drowning codes as the UCoD were G40-epilepsy (2.9%), I25-chronic ischaemic heart disease (1.7%) and R99-ill-defined and unknown cause of mortality (1.1%). Over half (52.7%) of the cases with ICD-10 coding available recorded a diagnostic code of T75.1 as a multiple cause.

There were 19 cases (1.3%) coded as intentional self-harm (X71) of which, on review, three were intentional. Five cases had consistent coding yet lacked corroborating evidence. In 11 cases, the ICD code was intentional; however, the coronial finding was left open implying that they should be coded to Y21-undetermined intent. There were zero cases (0.0%) coded assault by drowning and submersion (X92).

No drowning codes

There were 63 cases (4.4%), classified as drowning that did not have a primary drowning or drowning-related code as the UCoD or as a subsequent cause. Common non-drowning codes as the UCoD were R99-ill-defined and unknown cause of mortality (23.8%) and I251-atherosclerotic heart disease of native coronary artery (11.1%). Cases coded R-99 at level 1 were coded as such due to bodies being too decomposed to determine cause of death (26.7%), a body not being recovered (20.0%) or where an external-only autopsy was conducted (53.3%).

No ICD coding

There were 53 cases without ICD coding. This varied from a high of 19 cases in 2007 to a low in 2011 of five cases. Of these cases, 47 (88.7%) were closed (ie, no longer under investigation by the coroner). Forty cases (75.5%) were males and 23 (43.4%) were aged 18–54 years. Drowning deaths in ocean/harbour locations recorded the highest number of cases without ICD codes (13; 24.5%), followed by swimming pools (12; 22.6%) and river/creek/stream locations (10; 18.9%). When examining cases without ICD coding by activity being undertaken immediately prior to drowning, falls (17; 32.1%) were the leading activity, followed by swimming/recreating and watercraft-related incidents (10; 18.9% each).

Discussion

In Australia, during the study period, 61% of unintentional drowning deaths are captured when W65-74 codes are used at UCoD to estimate drowning incidents. This increases to 78% if primary drowning and drowning-related codes (T75.1, V90, V92, W65-74, X38 and Y21) are included; and when all drowning codes and multiple causes of death are allowed, it captures 92%.

Global implications

The disparities identified in this study have implications for LMICs. A high-income country like Australia, with well-resourced coronial systems, a sophisticated national statistics agency and organisations devoted to aquatic education, rescue and resuscitation, records a 40% disparity in drowning cases when primary drowning codes W65-74 as the UCoD only are used. LMICs with fewer resources for rescue, body retrieval, investigation and coding are likely to experience even higher under-representation of drowning in official statistics. This has implications for resource allocation to drowning prevention due to the impacts of undercounting on community, national and global estimates.2 We would encourage all countries to have multiple causes of death provided, thus allowing for a greater understanding of the impact of drowning and the development of multifaceted prevention strategies. All nations should be made aware of the challenges associated with, and prioritise the collection and utilisation of drowning data.

Water-related transport

Water-related transport poses a challenge for identifying drowning deaths. In this study, only 29% of watercraft-related drowning incidents had a code of W65-74. There is no easy solution currently using the ICD-10 external cause codes to separate out drowning-related watercraft incidents from other causes of death. This has implications for estimates of fatal drowning and therefore resource allocation for prevention in countries with a large number of water transportation-related drowning deaths such as Finland,20 Philippines42 and Uganda.43

Non-aquatic transport-related drownings

In Australia, non-aquatic transport-related drownings are most commonly as a result of driving across roads and causeways inundated during floods. Non-aquatic transport incidents are recorded with a UCoD of W65-74 in 13% of incidents, this under-representation has also been observed in New Zealand.17 The challenge of such incidents is that traditional drowning prevention stratagems may not be as effective as taking a road traffic-related approach. We posit that risk mitigation strategies for these drowning deaths may include early warning systems, flood depth markers, warning signage, bridges and culverts.44

Drowning cases without ICD-10 drowning codes

A small number of cases (4%) did not have an ICD drowning code. There were 36 different codes used as the UCoD, commonly medical conditions (5%), however some (1%) were also related to the inability to recover a body, advanced decomposition or external-only autopsy.

The use of R-99 coding for drowning cases where a body is not recovered or not recovered prior to advanced decomposition, is an issue that is also likely to disproportionately affect LMICs and countries without death registries and timely retrieval. It is also an issue likely to affect isolated areas within a country (such as rural and remote locations), locations and activities where people are more likely to be recreating around water alone and countries that experience natural disasters due to flooding and storm surges. Countries that experience mass drowning events such as those due to large-scale water transportation accidents are also likely to be affected by the use of R99. The scale of drowning due to such factors may therefore be under-reported, deprioritising effective prevention strategies.

The role of the coroner and the data collection agency

Linked with the use of R-99 codes for open cases without an assigned cause of death is the speed with which the coroner completes an investigation and closes a case. Deaths, including drowning, which are not certified by coroners before the ABS’ cut-off date may also be permanently miscoded.31

In federated countries such as Australia, where investigation by the coroner is undertaken at the state/territory or regional level, there are jurisdictional differences in resourcing, time taken to close cases, case documentation and coding of cause(s) of death.45 On a state and territory basis, the difference between jurisdictions with respect to cases with and without ICD coding ranged from 0.0% without ICD coding in the Australian Capital Territory to 6.7% in Queensland. This may lead to non-comparable estimates of drowning by jurisdiction on the basis of resourcing and case load, impacting resources for prevention.

The Database currently includes unintentional drowning cases only. This audit identified 1.3% of cases in the Database that the ABS had coded as intentional (X71). Such coding issues highlight why it may be easier to examine all drowning cases regardless of intent, although prevention strategies differ between unintentional and intentional drowning.

Prevention

An accurate count of the number of people who drown (both fatal and non-fatal) is important for prevention. The approach used can impact drowning mortality numbers as well as the profile. The proportion of cases without ICD coding decreased across the study period, which has implications for drowning statistics in Australia. Future research should examine if similar trends are occurring in other countries. This study may also provide the impetus for other countries to conduct similar reviews of their own systems, thereby improving the quality and comparability of drowning data collected worldwide, as well as assist in improving WHO definitions, coding and global estimates.

Examining deaths with multiple causes can provide rich data to aid in prevention.46 Contributory causes of death identified in this study include pre-existing medical conditions such as epilepsy and heart disease, and other external causes such as alcohol and drug toxicity. Since the introduction of multiple cause coding, NCIS data show that, on average, two causes (and conditions) per death would be lost if only the single underlying cause was recorded. This loss of information would be a particular problem for deaths attributed to external causes (injury, poisoning and violence), which are classified by the circumstances of death, rather than according to the nature of injury.32

Recognising risk factors will strengthen the evidence base for prevention and address the multiple causal factors of drowning. For example, for epilepsy-related drowning deaths, it is unclear if the prevention of such drowning deaths is best achieved through diagnosis and appropriate medication (treating the medical condition alone) or increased supervision around water for those with epilepsy. Research has identified epilepsy as contributing to increased risk of drowning among Australian children 0–14 years,47 and pre-existing medical conditions, particularly cardiac conditions, among elderly people who have drowned.29

Limitations

This study uses the Database of an Australian drowning prevention advocacy organisation, drawn from an online coronial database, as well as a range of other reports (eg, police, media and child death review) that need to be corroborated by multiple sources. It is still possible there may be missing data (eg, bodies missing at sea with no associated report). This information represents Australia only and as such, further work in other countries is required. There was variation in missing ICD codes across Australia (range 0.0% in the Australian Capital Territory and Western Australia to 6.7% in Queensland). Variation due to the time taken to close coronial cases and the reporting of official cause of death statistics may also impact data quality. The information is correct as of 31 December 2016. Coronial data are subject to change until closed (5.8% open cases).

Conclusion

Inclusion and exclusion in drowning mortality data collection and reporting produces substantial discrepancies that influence the illumination of the burden and resource allocation for prevention. This study found 61% of unintentional drowning deaths were captured when primary drowning codes were used (W65-74) as the UCoD only. Those cases not captured were commonly fatal drowning as a result of watercraft or non-aquatic transport incidents. When multiple cause codes were allowed, and an expanded number of ICD codes (T75.1, V90, V92, W65-74, X38 and Y21), this figure increased to 92%. Reporting of watercraft and non-aquatic transport-related drowning deaths is an ongoing challenge within the current ICD-10 external cause classification system. This has implications for the design of policy, advocacy and programme planning for drowning prevention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the Royal Life Saving Society - Australia to aid in the reduction of drowning. Research at Royal Life Saving Society - Australia is supported by the Australian Government. The Royal Life Saving National Fatal Drowning Database was developed using funds from the Australian Government and the support of the Australian National Coronial Information System (NCIS).

Footnotes

Contributors: AEP, RCF and JS conceptualised the study. AEP and RCF gathered the fatality data in the Database. AJM coded the data to ICD-10, critically revised the manuscript and approved the manuscript as submitted. AEP conducted the analysis. AEP and RCF drafted the manuscript and approved as submitted. PDB and JS provided some interpretation of the data, revised it critically and approved the manuscript as submitted.

Competing interests: AEP, RCF and AJM were responsible for collating data in the database from the Australian National Coronial Information System (NCIS).

Ethics approval: Victorian Department of Justice and Regulation Human Research Ethics Committee (CF/07/13729; CF/10/25057, CF/13/19798).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: With respect to the minimum dataset underlying this research, these data are available on request; however, as the data are via a third party (coronial data), ethical approval and permission from the data custodians, the Australian National Coronial Information System (NCIS) is required before the authors are able to provide their dataset to the person inquiring. There are strict ethical restrictions around use of these data and it can therefore not be sent to a public repository. Once ethical approval and permission from the NCIS as data custodians has been achieved, researchers can contact ncis@ncis.org.au to gain access to the data.

References

- 1.Haagsma JA, Graetz N, Bolliger I, et al. The global burden of injury: incidence, mortality, disability-adjusted life years and time trends from the Global Burden of Disease study 2013. Inj Prev 2016;22:3–18. 10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization. Global report on drowning: preventing a leading killer. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallis BA, Watt K, Franklin RC, et al. Where children and adolescents drown in Queensland: a population-based study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008959 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denehy M, Leavy JE, Jancey J, et al. This much water: a qualitative study using behavioural theory to develop a community service video to prevent child drowning in Western Australia. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017005 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Felton H, Myers J, Liu G, et al. Unintentional, non-fatal drowning of children: US trends and racial/ethnic disparities. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008444 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yin Z, Wu J, Luo J, et al. Burden and trend analysis of injury mortality in China among children aged 0-14 years from 2004 to 2011. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007307 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin CY, Wang YF, Lu TH, et al. Unintentional drowning mortality, by age and body of water: an analysis of 60 countries. Inj Prev 2015;21:e43–50. 10.1136/injuryprev-2013-041110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morgan D. Estimates of drowning morbidity and mortality adjusted for exposure to risk. Inj Prev 2011;17:359 10.1136/injuryprev-2011-040130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Purnell M, McNoe B. Systematic review of drowning interventions and risk factors and an international comparison of water safety policies and programs. Report to the accident compensation corporation. Injury Prevention Research Unit University of Otago; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith GS, Houser J. eds. Risk factors for drowning: a case-controlled study. 122nd anual meeting of the Amercian Public Health Association, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peden AE, Franklin RC, Leggat PA. Fatal river drowning: the identification of research gaps through a systematic literature review. Inj Prev 2016;22:202–9. 10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peden AE, Franklin RC, Queiroga AC. Epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for the prevention of global unintentional fatal drowning in people aged 50 years and older: a systematic review. Inj Prev 2017:doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2017-042351 [Epub ahead of print 3 Aug 2017]. 10.1136/injuryprev-2017-042351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine. National Coronial Information System (NCIS). 2017. www.ncis.org.au (accessed 5 Apr 2017).

- 14.Langley JD, Chalmers DJ. Coding the circumstances of injury: ICD-10 a step forward or backwards? Inj Prev 1999;5:247–53. 10.1136/ip.5.4.247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu TH, Lunetta P, Walker S. Quality of cause-of-death reporting using ICD-10 drowning codes: a descriptive study of 69 countries. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:30 10.1186/1471-2288-10-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davie G, Langley J, Samaranayaka A, et al. Accuracy of injury coding under ICD-10-AM for New Zealand public hospital discharges. Inj Prev 2008;14:319–23. 10.1136/ip.2007.017954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith GS, Langley JD. Drowning surveillance: how well do E codes identify submersion fatalities. Inj Prev 1998;4:135–9. 10.1136/ip.4.2.135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finch CF, Boufous S. Do inadequacies in ICD-10-AM activity coded data lead to underestimates of the population frequency of sports/leisure injuries? Inj Prev 2008;14:202–4. 10.1136/ip.2007.017251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woo JG, Zeller MH, Wilson K, et al. Obesity identified by discharge ICD-9 codes underestimates the true prevalence of obesity in hospitalized children. J Pediatr 2009;154:327–31. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.09.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lunetta P, Penttilä A, Sajantila A. Drowning in Finland: “external cause” and “injury” codes. Inj Prev 2002;8:342–4. 10.1136/ip.8.4.342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chowdhury SM, Rahman A, Mashreky SR, et al. The horizon of unintentional injuries among children in low-income setting: an overview from Bangladesh health and injury survey. J Environ Public Health 2009;2009:1–6. 10.1155/2009/435403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franklin RC, Scarr JP, Pearn JH. Reducing drowning deaths: the continued challenge of immersion fatalities in Australia. Med J Aust 2010;192:123–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barss P, Subait OM, Ali MH, et al. Drowning in a high-income developing country in the Middle East: newspapers as an essential resource for injury surveillance. J Sci Med Sport 2009;12:164–70. 10.1016/j.jsams.2007.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, et al. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1459–544. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2016. 3303.0 - Causes of Death, Australia. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Royal Life Saving Society - Australia. 2016. Royal Life Saving National Drowning Report 2016.

- 27. Australian Water Safety Council. Australian Water Safety Strategy 2016-2020. Sydney: Australian Water Safety Council, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Franklin RC, Pearn JH. Drowning for love: the aquatic victim-instead-of-rescuer syndrome: drowning fatalities involving those attempting to rescue a child. J Paediatr Child Health 2011;47:44–7. 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01889.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahony AJ, Peden AE, Franklin RC, et al. Fatal unintentional drowning in older people: an assessment of the role of preexisting medical conditions. Healthy Aging Research 2017;1:e7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peden AE, Franklin RC, Leggat PA. The hidden tragedy of rivers: a decade of unintentional fatal drowning in Australia. PLoS One 2016;11:e0160709 10.1371/journal.pone.0160709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Studdert DM. The modern coroner as injury preventer. Inj Prev 2016;22:311–3. 10.1136/injuryprev-2016-042076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine, National Coronial Information System (NCIS). 2017. www.ncis.org.au (accessed 9 Feb 2017).

- 33.Peden AE. Royal Life Saving Society - Australia Drowning Database Definitions and Coding Manual 2016. Sydney: Royal Life Saving Society - Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 34. World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision. World Health Organization, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Daking L. ICD codes and the NCIS. Royal Life Saving Society - Australia: National Coronial Information System, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine. ICD-10 Coding breakdown by jurisdiction and year. Victoria: National Coronial Information System, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 37. World Health Organization. WHO mortality database, 2004. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/cod/en/ (accessed 14 Jul 2017)

- 38. World Health Organization. Classification of diseases (ICD), 2017. http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/ (accessed 14 Jul 2017)

- 39. SPSS Inc. IBM SPSS statistics 20.0.0. Version 20.0.0 Chicago, Illinois: IBM; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keppel G. Design and analysis: a researcher’s handbook. 3rd edn Englewood Cliffs: NJ: Prentice Hall, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Passmore JW, Smith JO, Clapperton A. True burden of drowning: compiling data to meet the new definition. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot 2007;14:1–3. 10.1080/17457300600935148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martinez RE, Go JJ, Guevarra J. Epidemiology of drowning deaths in the Philippines, 1980 to 2011. Western Pac Surveill Response J 2016;7:1–5. 10.5365/wpsar.2016.7.2.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kobusingye O, Guwatudde D, Lett R. Injury patterns in rural and urban Uganda. Inj Prev 2001;7:46–50. 10.1136/ip.7.1.46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peden AE, Franklin RC, Leggat P, et al. Causal pathways of flood related river drowning deaths in Australia. PLoS Curr 2017. May 18 (Edition 1) 10.1371/currents.dis.001072490b201118f0f689c0fbe7d437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Daking L, Dodds L. ICD-10 mortality coding and the NCIS: a comparative study. Him J 2007;36:11–23. 10.1177/183335830703600204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fingerhut LA, Warner M. The ICD-10 injury mortality diagnosis matrix. Inj Prev 2006;12:24–9. 10.1136/ip.2005.009076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Franklin RC, Pearn JH, Peden AE. Drowning fatalities in childhood: the role of pre-existing medical conditions. Arch Dis Child 2017;102:888–93. 10.1136/archdischild-2017-312684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.