Background

Latinos living in the U.S. are disproportionately affected by HIV, with rates of new HIV infections almost three times higher than that of Whites.1–4 Latinos are also more likely to be diagnosed or present late to HIV care.5–9 Undiagnosed HIV is especially common among male and foreign-born Latinos.5–8,9–11 This is concerning because, among Latinos, men account for approximately 80% of all new HIV infections.12 Within the mainland U.S., 54% of new infections among Latinos occur in foreign-born individuals and 84% in urban residents.13

Over the last decades, foreign-born Latino males seeking economic opportunities have increasingly settled in areas of the country without long-standing Latino communities.14 Lack of culturally and linguistically appropriate services in emergent Latino areas have exacerbated existing health disparities, including HIV.15,16 Baltimore, Maryland, has an emergent Latino population that more than doubled between 2000 and 2010.17,18 In Baltimore neighborhoods with a high density of Latino residents, over 90% of Latinos are foreign-born, 82% speak only Spanish, and share characteristics similar to those in other rapid growth states on the east coast.19,20

Disparities in HIV among Latinos in Baltimore are evident. Since 2000, AIDS cases have decreased among non-Hispanic Blacks and non-Hispanic Whites, but have nearly doubled among Latinos, and mortality due to AIDS among Latinos is twice that of non-Latino Whites.21 As has been documented in other settings,6,17 Latinos in Baltimore are diagnosed with HIV later than other racial/ethnic groups. Such delays worsen HIV-associated morbidity and mortality and increase HIV transmission in the community.

In order to improve HIV testing services for Latinos, the Baltimore City Health Department (BCHD) established a culturally-competent HIV outreach program in 2008. Bilingual outreach workers conduct street and venue-based outreach using a mobile van where clients can get free HIV testing. The outreach workers have developed strong partnerships within the community and have gained high levels of trust by community members. Through the program, over 5000 foreign-born Latino men and women have tested for HIV..22,23 Patients diagnosed with HIV are counseled by the outreach workers and linked to HIV care at the BCHD HIV clinic, which is staffed with bilingual clinicians and case managers. Once in care, foreign-born Latinos do well, with high rates of antiretroviral coverage and virologic suppression.7,11,24,25

However, a high proportion of new patients still present symptomatically to the emergency room or inpatient setting. This suggests that while critical, overcoming language and cost barriers alone is not sufficient. Therefore, additional interventions to promote timely HIV diagnosis and linkage to care that are tailored to the needs of foreign-born Latino men are critically needed.

Objective

To address current gaps in services acquisition, a partnership was established between the BCHD Latino outreach team, community members and leaders, the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) Center for Social Design (CSD) and academic investigators from Johns Hopkins University (JHU) to develop an educational and motivational campaign to promote HIV testing among foreign-born Latino men. This manuscript describes the iterative process used by the partners that led to the development of ¡Solo Se Vive Una Vez! (You Only Live Once), a multilevel (individual and community) intervention.

Methods

Community Partnership

The BCHD Latino outreach team was established by one of the investigators (K. Page) in 2008. Since then, this team has worked in partnership with community organizations, community leaders and researchers at JHU to evaluate the program and inform changes. Partnering community organization representatives and community leaders were invited to join the current project alongside the Latino outreach team, JHU researchers and CSD partners. In 2013, a coalition of 8 community members and service providers was established to inform the Vive project, identify priorities, provide feedback and ensure that the intervention was relevant to the community’s experience. Coalition members were invited to participate based on their personal experiences as Latinos affected by HIV or working with the Latino community. All coalition participants (n=8) were Latino immigrants, and represented a range of age, countries of origin, time within the U.S., and personal and professional experience. In addition to the coalition, the intervention was developed through an iterative process that included the feedback from focus groups with representatives of the target population.

The CSD utilizes a collaborative, multidisciplinary design process combining visual and contextual research, analysis, visualization, design thinking, idea generation and communication to address social problems. Students can apply to enroll in practice-based studios led by MICA faculty, which are inter-disciplinary projects engaging undergraduate and graduate students with outside partners to address specific social problems. To develop materials for this intervention, CSD established a yearlong practice based studio project during the 2014–2015 academic year. The process of developing the intervention material included three phases: research/immersion, ideation and pitch (described below). Through this process, the students worked with the partners to develop the overall concept and messaging of the intervention, the campaign identity design and branding direction and the content of the individual intervention modules.

The lead outreach worker and 2 academic partners ( an anthropologist and a clinician, both bilingual) served as project directors and met weekly to discuss the intervention development progress. Meetings with the CSD faculty and students varied based on the stage of the design process. The community coalition met as a group at the start of the project to identify the focus areas of the efforts, and again to provide feedback on content and language when the intervention module designs and storylines were identified but not complete. The project directors were present at these meetings, as was one CDS student. Since none of the CSD students spoke Spanish, one student came as a representative to meet the coalition members and observe the process, and then reported back to his classmates. Additionally, one-on-one meetings occurred with coalition members throughout the process to provide updates and get feedback. These one-on-one meetings occurred between coalition members and the project directors as well as CSD students. Meetings among coalition members and CDS students were conducted in English, as all of the coalition partners were bilingual. When needed, the faculty and students met with a technician for eMocha to address concerns about the technological fit of ideas into the platform. Together, these efforts ensured that partners were engaged and informed at all times in the intervention development, while being respectful of each partner’s time and needs.

Conceptual Framework and Research/Immersion Phase

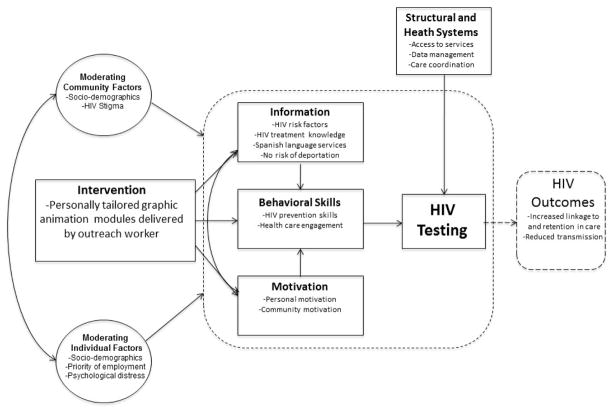

Through previous focus groups, we found that Latino immigrant men preferred receiving HIV information that was individually tailored, accessible in their environment (as opposed to clinical sites) and delivered by peers.26 Additionally, through a previous survey conducted among Latino immigrant men and women, high acceptability of receiving health and HIV-related information via cell phones was demonstrated.27 Therefore, the Latino outreach team and JHU partners reached out to faculty at the CSD with the idea of developing a technology-based intervention that could deliver personalized information to Latino immigrant men who refuse HIV testing during outreach. This subpopulation was prioritized given the high proportion of new HIV patients, particularly immigrant men, diagnosed late with HIV. The Latino outreach and academic partners had a conceptual framework developed based on their previous research from which the intervention should be based. In this framework (the situated Information, Motivation, Behavior framework [sIMB], Figure 1) relevant information, motivation and behavioral skills interact to determine HIV testing and health seeking behaviors.28

Figure 1.

situated Information, Motivation, Behavioral Skills (sIMB) framework for the ¡Solo Se Vive Una Vez! multilevel intervention.

This framework was used to develop the intervention modules based on the priorities identified by the community coalition through a nominal group technique (Table 1 or 2). Coalition members provided three responses to the question “why don’t Latino immigrant men in Baltimore get tested for HIV?” Answers were sorted and combined where appropriate and a list of unique responses was generated. Together, the coalition members discussed each unique response. Once all items were discussed and the group agreed that there were no other important reasons to discuss, the coalition members independently and anonymously ranked the items in order of importance. The highest ranked reasons, and therefore suggested focus areas of the intervention, were: 1) fear of HIV because of the association with death and lack of education of HIV (tie), 2) associations of HIV with homosexuality, 3) general stigma of HIV/AIDS and 4) lack of perceived risk.

Table 1.

Focus group participant characteristics (N = 75).

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age in years (mean, sd) | 37.8 (8.3) |

| Country of Origin | |

| El Salvador | 9 (12.0) |

| Guatemala | 1 (1.3) |

| Honduras | 40 (53.3) |

| Mexico | 19 (25.3) |

| Other | 6 (8.0) |

| Education | |

| Less than grade 6 | 48 (64.0) |

| Grades 7–12 | 11 (14.7) |

| Professional program or university studies | 16 (21.3) |

| Time in the U.S. | |

| Less than 1 year | 4 (5.3) |

| 1–5 years | 21 (28.0) |

| More than 5 years | 50 (66.7) |

| Time in Baltimore | |

| Less than 1 year | 6 (8.0) |

| 1–5 years | 30 (40.0) |

| More than 5 years | 39 (52.0) |

| Relationship Status | |

| Single | 35 (46.7) |

| In partnership, partner in country of origin | 19 (25.3) |

| In partnership, partner in the U.S. | 17 (22.7) |

| In partnership, partners in country of origin and U.S. | 3 (4.0) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (1.3) |

| Tested for HIV in the past year | 30 (40.0) |

Table 2.

sIMB intervention model components of the ¡Vive! modules.

| sIMB Components | Intervention Priority Area | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fear of HIV Diagnosis | Inaccurate Perception of Risk | Fear of Diagnosis/Inaccurate Perception of Risk (combination) | Competing Priorities | |

| Information |

|

|

|

|

| Motivation |

|

|

|

|

| Behavioral Skills | Access to HIV prevention, testing, and care resources and services | |||

Based on the findings from the nominal group technique, and findings from pprevious research and experience, the following were identified as the focus areas for the intervention: 1) fear of HIV diagnosis (e.g. not knowing that HIV treatment is effective, free and available regardless of immigration status), 2) inaccurate perception of risk (e.g. not knowing that HIV can be asymptomatic, associating HIV only with homosexuality) and 3) competing priorities, especially with work, that reduce concern about HIV testing. A videographic animation module was created for each of these priorities, and a fourth was created that combined fear of HIV diagnosis and inaccurate perception of risk, as both of these barriers are important for some Latino male immigrants.

A desired platform (eMocha) was also identified based on logistical consideration, previous research and evaluation ideas.29

Research/Immersion Phase

During the research and immersion stage of the CSD course, students learned about the specific problem to be addressed and the culture and context of the project. Partners gave presentations to the class on the impact of HIV among Latino immigrants, challenges associated with late diagnosis, the BCHD Latino outreach program activities and an overview of preliminary work, including the conceptual framework of the project. The students then visited Latino neighborhoods and the BCHD clinics and met with community coalition members.

Ideation Phase

Following the research period, students generates as many ideas as possible for an intervention aimed at increasing HIV testing among Latino immigrant men. Although the partners approached the students with specific desires for the intervention, the students were not limited to these restrictions. Students worked in groups and individually, and met with the partners to discuss and refine ideas. As part of the ideation process, four main messaging concepts emerged that could be used in the intervention. The students also generated a diverse range of design concepts, including guerrilla marketing campaign material, a LaboBar (offering STD/HIV testing in bathrooms) and the use of games aimed at encouraging HIV testing. The design concepts incorporated the slogans to create packages for each messaging concept. The individually-tailored and technology-based intervention component that could be used by the Latino outreach team was understood to be part of this package, although this was not yet conceptualized.

Pitch Phase

During the pitch phase, ideas generated from the ideation phase were presented to the target community. The pitch phase was an iterative process in which one component of the ideas was tested through focus groups with Latino immigrant men and then discussed by the partners before moving to the next component, now narrowed based on the findings of the previous focus groups. The components tested individually were concepts/messages, slogan design, color schemes and module design concepts created in this phase (including photographic, illustrative and typographic approaches).

Ten semi-structured focus groups with 75 Latino immigrants were conducted over an 8-month period in 2014 and 2015. Three focus groups were conducted for each component and one was conducted on the final product (with the audio portion of the intervention read aloud as this was not yet recorded). Eligibility requirements for the focus groups included being 18 years or older, male, foreign-born, self-identifying as Latino/Hispanic and willing to provide oral consent. Participants were recruited through outreach at open-air day labor pickup sites and a local workers center that services Latino immigrants.

Two Spanish-speaking moderators were present during each focus group; one moderated the focus groups and the other served as note taker to document nonverbal reactions of the participants. Focus groups lasted approximately 1.5–2 hours, and were conducted at a nearby restaurant or the workers center. Participants were provided (based on the component being discussed) printed samples of messages, logos designs (ranging from simple sans serif fonts to complex typographic designs), color schemes, stock photographs of Latino men and women, module formatting options (e.g., interactive quiz, educational video game, animated graphics) and story narratives. Participants were asked to share opinions of the various options provided, as well as provide alternative suggestions. At the completion of the focus group, participants completed a brief survey on demographics and HIV testing history (Table 1). Participants were provided a meal and $25 compensation for their time. The protocol was approved by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Results

Study participants

The community coalition included XX participants, of whom XX (%) were male, xx (%) Latino, representing the following countries: xxx, xxx, xx (X% were foreign-born). The primary occupation of the coalition members included: HIV social work (x), xxx, xxx, xxx Ten focus groups with participants that represented the target population were conducted during the development of the intervention. The mean age of the participants was 37.8 years, 64% had less than 6th grade education, 67% had been in the U.S. for more than 5 years, and 40% reported a previous test for HIV (Table 1)

Vive Intervention

Based on the findings from the nominal group technique, and findings from previous research, the following were identified as the focus areas for the intervention: 1) fear of HIV diagnosis (e.g. not knowing that HIV treatment is effective, free and available regardless of immigration status), 2) inaccurate perception of risk (e.g. not knowing that HIV can be asymptomatic, associating HIV only with homosexuality) and 3) competing priorities, especially with work, that reduce concern about HIV testing. Through the iterative process of partner discussion, community coalition meetings and focus group discussions, the ¡Sólo Se Vive Una Vez! (You Only Live Once) intervention campaign, or ¡Vive!, was created.

¡Vive! products include: 1) four graphic animation modules (with 3 storylines each) that address the 3 priorities identified above (and a 4th that combines fear of HIV diagnosis and inaccurate perception of risk, as both of these barriers are important for some Latino male immigrants) (Table 2) and 2) images and posters for a community-wide anti-stigma social marketing campaign. The graphic animation modules can be used to deliver individually-tailored information through tablets, cell phones, and computers. For example, when an outreach worker encounters a Latino immigrant man who is hesitant to get HIV tested, a short survey can be administered and a preprogrammed algorithm identifies the video module that addresses the person’s primary concern, thus providing information that is individually tailored. Depending on the needs and preferences of the community, the modules could also be more broadly disseminated in settings such as clinic waiting rooms or made accessible through social media or the internet.

The ¡Sólo Se Vive Una Vez! slogan was selected by focus group participants. Participants found that this message led them to pause and reflect about their lives, their families and the reason they had come to the U.S. The positive tone and life affirming content of the message dispelled fears associated with HIV and gave a sense of optimism and purpose. When specifically asked whether the message could encourage risky behavior, participants denied such associations.

In subsequent focus groups, participants were shown the message “Sólo se vive una vez” in various designs and fonts. The final logo design was created based on blending elements of designs shown that received positive feedback. Due to the simplicity of use and comprehension, focus group participants preferred graphic animation modules to relay the content of the intervention and identified components of storylines from samples presented that would be clear and logical. They also requested that photographs of the protagonists be included, but cautioned to be mindful of potential repercussions to local actors given the stigma associated with HIV in the community. Stock photos presented in focus groups were not well received, so the partners worked with a professional photographer in Chicago to photograph Latino models to avoid negative consequences to local individuals. The CSD team art directed the photo shoot, and ensured that the models were appropriately styled to reflect Baltimore norms.

The CSD students then refined the storylines for the focus areas of the individual intervention component and developed animated graphics using the preferred visual approach. For each priority, three short stories were created. The storylines incorporated the necessary information identified for each priority area based on the sIMB framework (Table 2). The photographs of the men were added at the beginning of each module, which then tells that man’s story. Each story, lasting approximately one minute long, is narrated by the protagonist, who confronts different barriers to testing for HIV and eventually takes a HIV test. Most of the men in the stories test negative; however, for the men who test positive, the viewer is shown that the protagonist has free access to medicine, is not at risk of deportation and can still live a healthy, productive life. Each story ends with the protagonist saying the campaign slogan, and information about HIV testing is provided at the end of each module.

The scripts were presented to Latino immigrant men in a focus group as well as the community coalition to provide feedback on clarity, comprehension and word choice. Once the scripts were finalized, the partners selected 6 professional Spanish-speaking voice actors with a range of accents reflecting those in the community to record the module scripts.

Based on the focus group discussions and relevant research, the partners decided to add a social marketing campaign aimed to reduce stigma in the community. Therefore, the photographer also shot photographs of Latino women, children and families. In the final focus group, the participants provided feedback on posters that complemented the modules and discussed additional social marketing campaign ideas. An iterative process with frequent feedback from the target audience, the community coalition and the partners led to multiple revisions and the final production the ¡Vive! (Live!) intervention components. The preferred visual approach of the individual intervention, which included photographs, typography and color palette selected by participants, was incorporated into all ¡Vive! materials to present a unified visual system and cohesive campaign.

Lessons Learned

The development of the ¡Vive! intervention would not have been possible without the diverse expertise of the team members. Academic investigators developed the conceptual framework for the project based on extensive formative work with the community and ensured accuracy of the educational information provided. The BCHD outreach team was instrumental in engaging the community, leveraging its network to establish the community coalition and providing feedback on the feasibility of ideas in the field. The coalition and focus groups provided real-time feedback that allowed the team to create a product that resonated with the community and reflected their experience. CSD faculty and students provided essential expertise in social design and in developing a product that appealed to the target audience.

At the initiation of the project, the CSD students and faculty had limited knowledge of HIV and barriers to care, were not familiar with the Latino community in Baltimore and none spoke Spanish fluently. Therefore, the first month of the design process was spent learning about the topic and the targeted audience, with opportunities to interact directly with members of the Latino community. While having a bilingual or bicultural student may have facilitated the process, the lack of familiarity also opened creative opportunities beyond pre-conceived notions of Latino artwork/design. During the first semester, the CSD team was given “free reign” for creative ideation, which led to proposals of varying feasibility in terms of logistical requirements and cultural adaptations. While not all suggestions were adopted, this process enhanced the engagement of the students, and helped inform the final design selected by the community.

Even though the outreach team and academic partners had ample experience working in HIV, particularly with the Latino community, the partnership and ongoing feedback mechanisms took the project in new directions and proved to be essential. For example, based on preliminary work, the outreach team and academic partners initially requested that CSD students develop video educational modules featuring live actors. However, the CSD team requested permission to explore other options. This led to the possibility of using a stylized, illustrative motion graphic design approach, which proved very appealing to community members and helped alleviate concerns about potential repercussions to actors associated with an HIV campaign. The conversations with the community about HIV-related stigma also led to the realization that the individualized modules would need to be paired with a community-level campaign to address stigma, which was an easy adaptation of the plan given the diverse ideas already explored through the ideation phase.

Conclusion

Delayed diagnosis of HIV among Latino immigrants, particularly men, remains a major obstacle to decreasing HIV-related morbidity and reducing transmission in the Latino community. HIV testing rates among those at highest risk for infection could improve with individualized approaches that motivate high risk individuals to get tested for HIV despite their reservations, and with interventions that can influence the social environment to reduce stigma as a barrier to engaging in care. In fact, studies support the use of multilevel interventions that include both individual and community level components that are complementary and can have synergistic impact on reducing HIV risk and improving engagement in care.30–32 A partnership of diverse expertise can be an important tool to developing approaches that are feasible and acceptable to the community, and ensuring that the messaging and design resonate with the targeted audience.33

Acknowledgments

This work was funded through a supplemental grant from the Johns Hopkins University Center for AIDS Research (P30AI094189).

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Internet] Monitoring selected national HIV prevention care objectives by using HIV surveillance data – United States and 6 U.S. dependent areas – 2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2012;17(3 Part A) [cited 2015 March 06]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Internet] Diagnoses of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States and Dependent areas, 2010. HIV Surveillance Report. 2012:22. [cited 2015 March 6]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_surveillance_report_vol_22.pdf.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Internet] HIV among Latinos. 2011 [cited 2013 April 02]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/resources/factsheets/pdf/latino.pdf.

- 4.Chen M, Rhodes PH, Hall IH, Kilmarx PH, Branson BM, Valleroy LA. Prevalence of undiagnosed HIV infection among persons aged ≥13 years--National HIV Surveillance System, United States, 2005–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(Suppl):57–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Late versus early testing of HIV – 16 sites, United States, 2000–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:581–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dennis AM, Napravnik S, Sena AC, Eron JJ. Late entry to HIV care among Latinos compared with non-Latinos in a southeastern US cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(5):480–487. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poon KK, Dang BN, Davila JA, Hartman C, Giordano TP. Treatment outcomes in undocumented Hispanic immigrants with HIV infection. PloS one. 2013;8(3):e60022. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Espinoza L, Hall HI, Selik RM, Hu X. Characteristics of HIV infection among Hispanics, United States 2003–2006. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(1):94–101. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181820129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen NE, Gallant JE, Page KR. A systematic review of HIV/AIDS survival and delayed diagnosis among Hispanics in the United States. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(1):65–81. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9497-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelley CF, Hernandez-Ramos I, Franco-Paredes C, del Rio C. Clinical, epidemiologic characteristics of foreign-born Latinos with HIV/AIDS at an urban HIV clinic. AIDS Read. 2007;17(2):73–74. 78–80, 85–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dennis AM, Wheeler JB, Valera E, Hightow-Weidman L, Napravnik S, Swygard H, et al. HIV risk behaviors and sociodemographic features of HIV-infected Latinos residing in a new Latino settlement area in the Southeastern United States. AIDS Care. 2013;25(10):1298–1307. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.764964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated Lifetime Risk for Diagnosis of HIV Infection Among Hispanics/Latinos --- 37 States and Puerto Rico, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(40):1297–1301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Geographic Differences in HIV Infection Among Hispanics or Latinos — 46 States and Puerto Rico, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(40):805–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.State of Maryland [Internet] Maryland State Data Center; 2010. [cited 2011 Dec 20]. Available from: http://census.maryland.gov/census2010/databyrace.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Subpopulation estimates from the HIV incidence surveillance system--United States, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(36):985–989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, Prejean J, An Q, Lee LM, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300(5):520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.United States Census Bureau [Internet] State & County QuickFacts Maryland. 2010 [cited 2013 Mar 16]. Available from: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/24000.html.

- 18.Acosta Y, de la Cruz G. The foreign born from Latin America and the Caribbean: 2010. American Community Survey Reports. 2011 [cited 2015 Jan 07]. Available from: http://www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/acsbr10-15.pdf.

- 19.Baltimore City Health Department [Internet] The Health of Latinos in Baltimore City, 2011. 2011 [cited 2015 Jan 07]. Available from: http://health.baltimorecity.gov/sites/default/files/Health%20of%20Latinos%20in%20Baltimore%20City%202011%20%28English%29.pdf.

- 20.Munoz B, O’Leary M, Fonseca-Becker F, Rosario E, Burguess I, Aguilar M, et al. Knowledge of diabetic eye disease and vision care guidelines among Hispanic individuals in Baltimore with and without diabetes. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(7):968–974. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.7.968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene [Internet] Baltimore City HIV/AIDS Epidemiological Profile Fourth Quarter 2011. 2011 [cited 2015 Feb 18]. Available from: http://phpa.dhmh.maryland.gov/OIDEOR/CHSE/Shared%20Documents/Baltimore%20City%20HIV%20AIDS%20Epidemiological%20Profile%2012-2011.pdf.

- 22.Chen N, Erbelding E, Yeh HC, Page K. Predictors of HIV testing among Latinos in Baltimore City. J Immgr Minor Health. 2010;12(6):867–874. doi: 10.1007/s10903-009-9297-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen NE, Meyer JP, Bollinger R, Page KR. HIV testing behaviors among Latinos in Baltimore City. J Immgr Minor Health. 2012;14(4):540–551. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9573-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McFall AM, Dowdy DW, Zelaya CE, Murphy K, Wilson TE, Young MA, et al. Understanding the disparity: predictors of virologic failure in women using highly active antiretroviral therapy vary by race and/or ethnicity. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64(3):289–298. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a095e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simoni JM, Huh D, Wilson IB, Shen J, Goggin K, Reynolds NR, et al. Racial/Ethnic disparities in ART adherence in the United States: findings from the MACH14 study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(5):466–472. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825db0bd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dolwick Grieb SM, Desir F, Flores-Miller A, Page K. Qualitative assessment of HIV prevention challenges and opportunities among Latino immigrant men in a new receiving city. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17(1):118–124. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9932-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leite L, Buresh M, Rios N, Conley A, Flys T, Page KR. Cell phone utilization among foreign-born Latinos: A promising tool for dissemination of health and HIV information. J Immigr Minor Health. 2014;16(4):661–669. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9792-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amico K. A situated-Information Motivation Behavioral Skills Model of Care Initiation and Maintenance (sIMB-CIM): An IMB Model Based Approach to Understanding and Intervening in Engagement in Care for Chronic Medical Conditions. J Health Psychol. 2011;16(7):1071–1081. doi: 10.1177/1359105311398727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.emocha® Mobil Health, Inc. [Internet] emocha® Mobil Health, Inc; 2015. [cited 2015 Mar 20]. Available from: http://www.emocha.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coates T, Kulich M, Celentano D, Zelaya CE, Chariyalertsak S, Chingono A, et al. Effect of community-based voluntary counselling and testing on HIV incidence and social and behavioural outcomes (NIMH Project Accept; HPTN 043): a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(5):e267–277. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70032-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DiClemente RJ, Jackson JM. Towards an integrated framework for accelerating the end for the global HIV epidemic among young people. Sex Educ. 2014;14(5):609–621. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2014.901214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beyrer C, Baral S, Kerrigan D, El-Bassel N, Bekker LG, Celentano DD. Expanding the space: inclusion of most-at-risk populations in HIV prevention, treatment, and care services. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57(Suppl 2):S96–99. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31821db944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rhodes SD, Duck S, Alonzo J, Ulloa JD, Aronson RE. Using community-based participatory research to prevent HIV disparities: assumptions and opportunities identified by the Latino partnership. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(Suppl 1):S32–35. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182920015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]