Abstract

Background

Hepatitis E infection is a global disorder that causes substantial morbidity. Numerous neurologic illnesses, including Guillain–Barre syndrome (GBS), have occurred in patients with hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection.

Case presentation

We report a 58 year-old non-immunocompromised man who presented with progressive muscle weakness in all extremities during an episode of acute HEV infection, which was confirmed by measuring the anti-HEV IgM antibodies in the serum. Both cerebrospinal fluid examination and electrophysiological study were in agreement with the diagnosis of HEV-associated GBS. Following the treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin, the patient’s neurological condition improved rapidly.

Conclusions

HEV infection should be strongly considered in patients with neurological symptoms, especially those with elevated levels of liver enzymes.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12879-018-2959-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Hepatitis E infection, Guillain–Barre syndrome, Viral hepatitis, Extra-hepatic manifestations

Background

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection, one of the most common causes of acute viral hepatitis, is an important public-health concern and leads to substantial morbidity [1]. HEV causes acute and chronic hepatitis, but most of these infections are asymptomatic [2]. In symptomatic patients, HEV can cause fulminant acute hepatitis, fibrosis, or cirrhosis [3, 4] Numerous extra-hepatic manifestations, including many neurological illnesses, are associated with acute or chronic hepatitis E [5]. In this article, we report a rare case of a patient clinically diagnosed with Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS) due to acute HEV infection. We also reviewed English language scientific literature for the clinical characteristics of HEV associated with GBS.

Case presentation

A 58 year-old non-immunocompromised man presented general fatigue, anorexia, cough, mild jaundice, and excretion of tea-colored urine for 7 days. He was referred to a local hospital, wherein his liver function tests showed elevated levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 273 U/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 664 U/L, total bilirubin at 51.8 μmol/L, and conjugated bilirubin at 20.5 μmol/L. Serological study was positive for IgM antibodies for HEV. A working diagnosis of acute hepatitis E was performed, and liver protection treatment was applied to the patient. However, on the 4th day of admission, the patient complained about progressive muscle weakness on his lower limbs, numbness, and abnormal pinprick sensation in his plantar that render him unable to walk. The patient was subsequently transferred to our hospital for further treatment because of the rapidly progressive symmetrical weakness of his lower and upper limbs.

The patient had a history of recovered schistosomiasis. He had never been exposed to a polluted environment or affected animals. He also had no history of blood transfusions, risky sexual behavior, or drug addiction.

Upon admission, general examination on the patient revealed unremarkable findings. His temperature was 36.4 °C, and his blood pressure was 130/99 mmHg. Physical examination showed asthenia, jaundice, blepharoptosis, and paresthesia. His cranial nerve examination showed unilateral facial nerve palsy, Romberg’s sign and the straight leg raising test was positive. Motor weakness was present in all limbs, with power of 4/5 in the upper limbs and 2/5 in the lower limbs. His triceps, biceps, and brachioradialis reflexes were normal, whereas his patellar and Achilles tendon reflexes were absent bilaterally. Two days after admission, he developed dysphagia, choking, areflexia and labored breathing. Neurological examination showed and unilateral cranial palsy with left blepharoptosis, flat nasolabial fold and incomplete eyelid closure of right side. Muscle weakness in his four limbs progressed rapidly. The power of the upper extremity was 2/5 for the proximal muscles and 4/5 for the distal muscles. The power grade of both proximal and distal legs was 1/5. GBS was suspected, and lumbar puncture was conducted on the 2nd day. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination showed 0/μL monocyte, 4.6 mmol/L glucose level, and 275.3 mg/dL protein level, which suggested albuminocytologic dissociation. Nerve conduction studies showed evidence of demyelinating neuropathy with dysfunction of motor and sensory nerve fibers.

Laboratory investigations showed 20 μmol/L total bilirubin, 10 μmol/L conjugated bilirubin, 126 U/L alanine aminotransferase, and 160 U/L gamma-glutamyl transpepidase. Serologic studies for IgM and IgG anti-HEV were both positive. No serological evidence was found for hepatitis A virus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, hepatitis D virus, and syphilis or human immunodeficiency virus. Epstein–Barr virus and cytomegalovirus serology indicated positive IgG. Serum antibodies to anti-ganglioside antibodies GM1 and GM2 were negative, while the level of serum immunoglobulin G was increased.

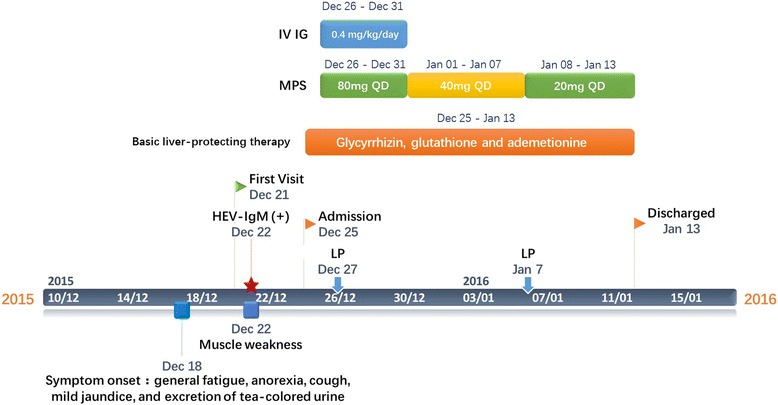

Cerebral computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging scans indicated normal results. (The clinical course is summarized in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Medical History. IVIg: intravenous immunoglobulin; MPS: Methylprednisolone; LP: lumbar puncture

The clinical history, physical examination, and biochemical findings of the patient were consistent with the diagnosis of acute HEV-associated GBS. He was treated with intravenous immunoglobulin at a dose of 0.4 mg/kg per day for 5 days. Meanwhile, methylprednisolone were also used to suppress inflammatory response. Glycyrrhizin, glutathione, and ademetionine were simultaneously administered for liver therapy. During the next 2 weeks, his clinical condition and muscle power improved gradually, and the patient had no complaints of respiratory distress or malaise. Repeat CSF examination 2 weeks after admission revealed 10/μL monocyte and 85.7 mg/dL protein level. At discharge, the patient had 5/5 power bilaterally in his arms and 4/5 power bilaterally in his legs. A month later, his liver function substantially improved, and his serum levels of AST and ALT were nearly normal. Six months after discharge, serological study (Wantai HEV-IgM ELISA) showed that IgM anti-HEV antibodies became negative, which suggested full recovery from the acute phase of hepatitis E. The patient responded well to treatment with his muscle power returning to normal, but still felt weakness in his right arm.

Discussion and conclusions

HEV, previously known as waterborne or enterically transmitted viral hepatitis, is hyper-endemic in many developing countries and endemic in developed countries [6]. Aside from hepatitis symptoms, HEV-associated neurological injuries also cause significant morbidity. Neurologic complications develop in 7 (5.5%) out of 126 patients with acute and chronic HEV infections in the United Kingdom and France [7]. The clinical spectrum of neurological injury is broad. GBS and neuralgic amyotrophy are the most frequently reported conditions [8]. Other neurological disorders include transverse myelitis, encephalitis, cranial nerve palsy, and meningoradiculitis [9, 10].

GBS is an acute immune-mediated polyradiculoneuropathy that results in rapidly progressing symmetric motor paralysis, limb palsy, hypoflexia, areflexia, and other neurological disorders. GBS is also a heterogeneous disorder with several forms, including acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP), acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN), acute motor–sensory axonal neuropathy (AMSAN), and Miller Fisher syndrome (MFS). GBS is usually preceded by an infection, which evokes an immune response that cross-reacts with peripheral nerve components via molecular mimicry [11]. Anti-ganglioside GM1or GM2 positive has been measured in three out of six cases of HEV-associated GBS. This condition may lead to autoimmune inflammatory polyneuropathy [12–17].

A literature review was performed using the PubMed database to identify other published cases and clarify the clinical characteristics of HEV-associated GBS. We used combinations of keywords, including hepatitis E and Guillain–Barre syndrome, and hepatitis E and MFS. Fifty-two cases described HEV-associated GBS. With the addition of our patient, 53 cases were counted, and the clinical characteristics of these cases are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of the reported patients was 47 years (20–73 years), and most of them are middle-aged men (30 men out of 53 cases: 57.7%). These patients developed HEV-associated GBS within an acute onset and have experienced hepatitis symptoms, including jaundice, malaise, nausea, and vomiting. GBS symptoms include motor weakness, cranial nerve palsy, and sensory disorder, which usually manifest after the occurrence of hepatitis symptoms. The mean delay between acute hepatitis E and GBS symptoms was 12 days (with a range of 3–73). Genotyping was performed among 11patients. Most of these patients revealed type 3, which suggested that HEV3 had high tropism of GBS. Most of our reviewed cases were found in Western Europe and Southern and Eastern Asia, where genotype 3 is prevalent. HEV RNA was found in the serum of 17 patients. Furthermore, HEV RNA was positive in the serum and the CSF of one patient.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of HEV-associated GBS

| Reference | Country | No. of cases | Age | Sex | Delay hepatitis neurological manifestation | Nerve conduction study | Anti-glycoprotein antibody | IgM | HEV RNA | HEV genotype | ALT (IU/L) | CSF | Treatment | Recovery/Delay | Comorbidity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilirubin(μmol/L) | Protein level, mg/dL | Cell count (×10^6/L) | |||||||||||||||

| Sood 2000 [13] | India | 1 | 50 | M | 5 days | AIDP | NT | + | NT | NT | 114 | 242.82 | 186 | 0 | Supportive | Full/1 month | None |

| Kumar 2002 [16] | India | 1 | 35 | M | 17 days | AMSAN | NT | + | NT | NT | 752 | 91.8 | NT | NT | MV/IVIg | Full/2 weeks | None |

| Kamani 2005 [12] | India | 1 | 58 | F | 9 days | NT | NT | + | NT | NT | 1448 | 40.7 | 80 | 2 | IVIg/PP | Full/12 days | None |

| Khanam 2008 [19] | Bangladesh | 1 | 20 | M | 10 days | AIDP&AMSAN | NT | + | NT | NT | 2509 | 61.56 | 190 | 0 | MV | Full/12 days | None |

| Loly 2009 [14] | Belgium | 1 | 66 | M | Few days | AIDP | GM2+ | + | NT | NT | 1813 | NM | 172.2 | NM | IVIg | Full/4 months | None |

| Cronin 2011 [15] | Ireland | 1 | 40 | M | Concomitant | AIDP | GM2+ | + | NT | NT | 57 | NM | >500 | 0 | MV/IVIg/PP | Full/6 months | None |

| Kamar 2011 [7] | France | 1 | 60 | F | Concomitant | AIDP | NT | + | Serum+ CSF- |

3f | 384 | 35 | 200 | 14 | IVIg | Partial/18 months | None |

| Maurissen 2012 [17] | Belgium | 1 | 51 | F | Concomitant | AIDP | GM1&GM2+ | + | Serum+ | NT | 2704 | NM | 61 | 15 | IVIg | Full/1 week | None |

| Del Bello 2012 [20] | France | 1 | 65 | M | Concomitant | AIDP | NT | + | Serum+ | 3f | 2000 | NM | 64 | 0 | MV/IVIg/Ribavirin | partial/2 month | Severe myositis |

| Tse 2012 [21] | Hong Kong | 1 | 60 | F | 3 days | AIDP | NT | + | NT | NT | 2858 | 60 | NM | NM | PP | Full/1 month | None |

| Santos 2013 [22] | Portugal | 1 | 58 | M | 17 days | AIDP | NT | + | Serum+ | 3a | 2320 | 114.74 | 181 | 4 | MV/IVIg | partial/2 month | None |

| Sharma 2013 [23] | India | 1 | 27 | M | 40 days | AIDP | NT | + | NT | NT | NM | NM | 243 | <5 | IVIg | Full/NM | None |

| Geurtsvan-Kessel 2013 [24] | Bangladesh | 11 | mean: 24 | NM | NM | NM | NT | + | Serum+(n = 1) | 1(n = 1) | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | None |

| van den Berg 2014 [25] | Netherlands | 10 | mean: 54 | 6 M, 4F | Mean: 5 days | AIDP(n = 5) AMAN(n = 1) AMSAN(n = 1) Equivocal(n = 2) Inexcitable(n = 1) |

NT | + | Serum+(n = 3) CSF-(n = 10) |

3 | Mean: 160.9 | Mean: 13.3 | NM | Mean:4.2 | NM | NM | NM |

| Chen 2014 [26] | China | 1 | 64 | M | 5 days | AIDP | GM2+ | + | NT | NT | 1461 | 156.9 | 88 | 10 | MV/IVIg | Full/12 months | Encephalitis |

| Scharn 2014 [27] | Germany | 1 | 50 | M | 7 days | AIDP & AMAN | – | + | Serum+ CSF- | 3c | 334 | NM | 81 | <1 | IVIg | Partial/5 months | None |

| Woolson 2014 [28] | NM | 1 | 42 | M | NM | NM | NT | + | Serum+ | 3 | 623 | 16 | 127 | 145 | NM | Full/3 months | None |

| Comont 2014 [29] | France | 1 | 73 | M | Concomitant | NM | GM1+ | + | Serum+ CSF+ | 3f | 822 | 101 | 137 | NM | IVIg | Full/2 months | None |

| Bandyopadhyay 2015 [30] | Japan | 1 | 43 | F | 14 days | AIDP & AMAN | GM1+ | + | Serum+CSF- | 3 | 1950 | 85.5 | 350 | 12 | MV/IVIg | Partial/NM | None |

| Higuchi 2015 [31] | Japan | 1 | 49 | M | 10 days | AIDP | – | + | Serum+ | 3 | 1246 | 15.4 | 102 | 7 | IVIg | Full/3 months | None |

| Perrin 2015 [32] | France | 2 | Mean: 57 | 1F, 1 M | Few days | AIDP | NT | + | Serum+(n = 1) | 3f | Mean:216 | Mean:20.6 | Mean:173 | NM | IVIg | Partial (n = 2)/Mean: 9 weeks | None |

| Fukae 2016 [33] | Japan | 3 | Mean: 53 | 3 M | NM | AIDP(n = 1) MSF(n = 1) |

GM1 + (n = 1) GQ1b + (n = 1) |

+ | Serum+(n = 1) | NT | Mean: 230.3 | NM | Mean: 91 | Mean:5 | IVIg | Full (n = 2) partial(n = 1)/NM |

None |

| Ji 2016 [34] | South Korea | 1 | 58 | M | 75 days | NM | NT | + | NT | NT | 525 | 23.59 | 44.6 | 0 | IVIg | Full/12 months | None |

| Lei 2017 [35] | China | 1 | 30 | M | Concomitant | AIDP | NT | + | NT | NT | 4502 | 83.96 | 344.19 | 0 | IVIg | Full/3 months | None |

| Stevens 2017 [36] | Belgium | 6 | Mean:61 | 4 M, 2F | NM | AIDP(n = 1) AMSAN(n = 1) Equivocal(n = 1) Demyelinating(n = 2) Sensory neuropathy(n = 1) |

– | + | Serum+(n = 2) | NT | Mean:762 | Mean:39.27 | Mean:69.4 | Mean:4.8 | IVIg(n = 4) PP(n = 1) supportive(n = 1) |

Partial (n = 5)/3–6 months Death(n = 1)/1 month |

NM |

| Our case | China | 1 | 58 | M | 11 days | AIDP | – | + | NT | NT | 664 | 51.8 | 275.3 | 0 | IVIg | Full/6 months | None |

F female, M male, HEV hepatitis E virus, ALT alanine aminotransferase, + positive, − negative, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, AIDP acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, AMAN acute motor axonal neuropathy, AMSAN acute motor–sensory axonal neuropathy, MSF Miller Fisher syndrome, NM not mentioned, NT not tested, MV mechanical ventilation, IVIg intravenous immunoglobulin, PP plasmapheresis

Among the 47 cases with available details of nerve conduction studies, 23(48.9%) had experienced AIDP. Other variants of GBS, including AMAN, AMSAN, and sensory neuropathy, were also detected. Anti-ganglioside GM1, anti-ganglioside GM2, and GQ1b were detected in eight patients. Thus, the pathogenesis of GBS-associated HEV may be related to GM1, GM2, and GQ1b antibodies. Among the 31 cases with available details of treatments, 25 used intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg), 4 used plasmapheresis (PP), and 1 used ribavirin. Some patients recovered spontaneously without IVIg or PP administration. Mechanical ventilation was performed in seven patients due to the involvement of respiratory muscles. Almost all the reviewed patients achieved complete neurological recovery within several weeks to several months, which suggested good prognosis for HEV-associated GBS. However, one patient died after cardiac arrest 1 month after the onset of neurological symptoms.

In conclusion, GBS is an emerging extrahepatic manifestation of HEV infection. HEV infection should be strongly considered in patients with neurological symptoms, especially those with elevated levels of liver enzymes. In our case, HEV infection was confirmed by IgM anti-HEV in the serum. This infection could also be supported by HEV RNA. CSF examination showed an increased level of proteins alongside with pleocytosis, which is supported with the suspicion of GBS. Nevertheless, the elevation of CSF proteins is frequent in encephalitis or encephalopathy as well. Thus, the diagnosis of GBS should be cautious. In removes under other resembling disease’s premise. Testing for HEV genotype and anti-ganglioside antibodies will likely help in further studying the pathogenesis of HEV-associated GBS.

HEV infection is a self-limiting disorder, and most patients require no treatment. IVIg and PP are both effective treatments for GBS. However, IVIg has replaced PP as the first line of treatment in most hospitals due to the convenience and availability of the former [18]. There is no significant difference between intravenous methylprednisolone with IVIg or IVIg alone.

Additional files

Liver function after admission in our hospital. The patient’s liver function tests showed showed 20 μmol/L total bilirubin, 10 μmol/L conjugated bilirubin, 126 U/L alanine aminotransferase, and 160 U/L gamma-glutamyl transpepidase. (DOCX 16 kb)

Serologic studies for hepatitis virus. Serologic studies for IgM and IgG anti-HEV were both positive. No serological evidence was found for hepatitis A virus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, hepatitis D virus. (DOCX 15 kb)

Serological study for HBV, HCV, Syphilis and HIV. Serologic studies for hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, syphilis or human immunodeficiency virus was negative. (DOCX 15 kb)

Serological study for Epstein–Barr virus and cytomegalovirus. Epstein–Barr virus and cytomegalovirus serology indicated positive IgG. (DOCX 14 kb)

The first cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination showed 0/μL monocyte, 4.6 mmol/L glucose level, and 275.3 mg/dL protein level. (DOCX 15 kb)

The second cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination revealed 10/μL monocyte and 85.7 mg/dL protein level. (DOCX 15 kb)

Liver function (one month later after discharge). A month later, the liver function of the patient substantially improved, and his serum levels of AST and ALT were nearly normal. (DOCX 16 kb)

Serological study for HEV(six months later). Six months after discharge, serological study showed IgM anti-HEV antibodies became negative. (DOCX 15 kb)

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data and materials are presented within Additional files 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8.

Abbreviations

- AIDP

Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- AMAN

Acute motor axonal neuropathy

- AMSAN

Acute motor-sensory axonal neuropathy

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- GBS

Guillain–Barre syndrome

- HEV

Hepatitis E virus

- IVIg

Intravenous immunoglobulin

- MFS

Miller Fisher syndrome

- PP

Plasmapheresis

Authors’ contributions

XZ carried out the data collection, literature review and drafting of the manuscript. LY and QX contributed to the drafting of the manuscript and aided in the literature review. SG participated in the data collection and the drafting of the manuscript. LT help to draft the manuscript and revised the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this investigation was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, and the reference number was 2017658.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12879-018-2959-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Xiaoqin Zheng, Email: zxq13920817821@163.com.

Liang Yu, Email: yuliangzju@163.com.

Qiaomai Xu, Email: xqmzju@126.com.

Silan Gu, Email: gusilan880529@126.com.

Lingling Tang, Email: 1196040@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Dalton HR, Bendall R, Ijaz S, Banks M. Hepatitis E: an emerging infection in developed countries. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8(11):698–709. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70255-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu FC, Zhang J, Zhang XF, Zhou C, Wang ZZ, Huang SJ, Wang H, Yang CL, Jiang HM, Cai JP, et al. Efficacy and safety of a recombinant hepatitis E vaccine in healthy adults: a large-scale, randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9744):895–902. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bazerbachi F, Haffar S. Acute fulminant vs. acute-on-chronic liver failure in hepatitis E: diagnostic implications. Infect Dis (Lond) 2015;47(2):112. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2014.968612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamar N, Izopet J, Dalton HR. Chronic hepatitis e virus infection and treatment. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2013;3(2):134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalton HR, Kamar N, van Eijk JJ, Mclean BN, Cintas P, Bendall RP, Jacobs BC. Hepatitis E virus and neurological injury. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12(2):77–85. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee GY, Poovorawan K, Intharasongkroh D, Sa-Nguanmoo P, Vongpunsawad S, Chirathaworn C, Poovorawan Y. Hepatitis E virus infection: epidemiology and treatment implications. World J Virol. 2015;4(4):343–355. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v4.i4.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamar N, Bendall RP, Peron JM, Cintas P, Prudhomme L, Mansuy JM, Rostaing L, Keane F, Ijaz S, Izopet J, et al. Hepatitis E virus and neurologic disorders. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(2):173–179. doi: 10.3201/eid1702.100856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheung MC, Maguire J, Carey I, Wendon J, Agarwal K. Review of the neurological manifestations of hepatitis E infection. Ann Hepatol. 2012;11(5):618–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandal K, Chopra N. Acute transverse myelitis following hepatitis E virus infection. Indian Pediatr. 2006;43(4):365–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bazerbachi F, Haffar S, Garg SK, Lake JR. Extra-hepatic manifestations associated with hepatitis E virus infection: a comprehensive review of the literature. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2016;4(1):1–15. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gow001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuki N, Hartung HP. Guillain-Barre syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(24):2294–2304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1114525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamani P, Baijal R, Amarapurkar D, Gupte P, Patel N, Kumar P, Agal S. Guillain-Barre syndrome associated with acute hepatitis E. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2005;24(5):216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sood A, Midha V, Sood N. Guillain-Barre syndrome with acute hepatitis E. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(12):3667–3668. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loly JP, Rikir E, Seivert M, Legros E, Defrance P, Belaiche J, Moonen G, Delwaide J. Guillain-Barre syndrome following hepatitis E. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(13):1645–1647. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cronin S, McNicholas R, Kavanagh E, Reid V, O'Rourke K. Anti-glycolipid GM2-positive Guillain-Barre syndrome due to hepatitis E infection. Ir J Med Sci. 2011;180(1):255–257. doi: 10.1007/s11845-010-0635-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar R, Bhoi S, Kumar M, Sharma B, Singh B, Gupta B. Guillain-Barré syndrome and acute hepatitis E: a rare association. JIACM. 2002;4(3):389–391. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maurissen I, Jeurissen A, Strauven T, Sprengers D, De Schepper B. First case of anti-ganglioside GM1-positive Guillain-Barre syndrome due to hepatitis E virus infection. Infection. 2012;40(3):323–326. doi: 10.1007/s15010-011-0185-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Doorn PA, Ruts L, Jacobs BC. Clinical features, pathogenesis, and treatment of Guillain-Barre syndrome. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(10):939–950. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khanam RA, Faruq MO, Basunia RA, Ahsan AA. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with acute HEV hepatitis. Med Coll J. 2008;1(2):32–34. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Del Bello A, Arne-Bes MC, Lavayssiere L, Kamar N. Hepatitis E virus-induced severe myositis. J Hepatol. 2012;57(5):1152–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tse AC, Cheung RT, Ho SL, Chan KH. Guillain-Barre syndrome associated with acute hepatitis E infection. J Clin Neurosci. 2012;19(4):607–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2011.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santos L, Mesquita JR, Rocha PN, Lima-Alves C, Serrao R, Figueiredo P, Reis J, Simoes J, Nascimento M, Sarmento A. Acute hepatitis E complicated by Guillain-Barre syndrome in Portugal, December 2012--a case report. Euro Surveill. 2013;18(34):6–9. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2013.18.34.20563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma B, Nagpal K, Bakki SR, Prakash S. Hepatitis E with Gullain-Barre syndrome: still a rare association. J Neuro-Oncol. 2013;19(2):186–187. doi: 10.1007/s13365-013-0156-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geurtsvankessel CH, Islam Z, Mohammad QD, Jacobs BC, Endtz HP, Osterhaus AD. Hepatitis E and Guillain-Barre syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(9):1369–1370. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van den Berg B, van der Eijk AA, Pas SD, Hunter JG, Madden RG, Tio-Gillen AP, Dalton HR, Jacobs BC. Guillain-Barre syndrome associated with preceding hepatitis E virus infection. Neurology. 2014;82(6):491–497. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen XD, Zhou YT, Zhou JJ, Wang YW, Tong DM. Guillain-Barre syndrome and encephalitis/encephalopathy of a rare case of northern China acute severe hepatitis E infection. Neurol Sci. 2014;35(9):1461–1463. doi: 10.1007/s10072-014-1731-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scharn N, Ganzenmueller T, Wenzel JJ, Dengler R, Heim A, Wegner F. Guillain-Barre syndrome associated with autochthonous infection by hepatitis E virus subgenotype 3c. Infection. 2014;42(1):171–173. doi: 10.1007/s15010-013-0448-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woolson KL, Forbes A, Vine L, Beynon L, McElhinney L, Panayi V, Hunter JG, Madden RG, Glasgow T, Kotecha A, et al. Extra-hepatic manifestations of autochthonous hepatitis E infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40(11–12):1282–1291. doi: 10.1111/apt.12986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Comont T, Bonnet D, Sigur N, Gerdelat A, Legrand-Abravanel F, Kamar N, Alric L. Acute hepatitis E infection associated with Guillain-Barre syndrome in an immunocompetent patient. Rev Med Interne. 2014;35(5):333–336. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bandyopadhyay D, Ganesan V, Choudhury C, Kar SS, Karmakar P, Choudhary V, Banerjee P, Bhar D, Hajra A, Layek M, et al. Two uncommon causes of Guillain-Barre syndrome: hepatitis E and Japanese encephalitis. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2015;2015:759495. doi: 10.1155/2015/759495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higuchi MA, Fukae J, Tsugawa J, Ouma S, Takahashi K, Mishiro S, Tsuboi Y. Dysgeusia in a patient with Guillain-Barre syndrome associated with acute hepatitis E: a case report and literature review. Intern Med. 2015;54(12):1543–1546. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.54.3506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perrin HB, Cintas P, Abravanel F, Gerolami R, D'Alteroche L, Raynal JN, Alric L, Dupuis E, Prudhomme L, Vaucher E, et al. Neurologic disorders in Immunocompetent patients with autochthonous acute hepatitis E. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(11):1928–1934. doi: 10.3201/eid2111.141789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukae J, Tsugawa J, Ouma S, Umezu T, Kusunoki S, Tsuboi Y. Guillain-Barre and miller fisher syndromes in patients with anti-hepatitis E virus antibody: a hospital-based survey in Japan. Neurol Sci. 2016;37(11):1849–1851. doi: 10.1007/s10072-016-2644-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ji SB, Lee SS, Jung HC, Kim HJ, Kim HJ, Kim TH, Jung WT, Lee OJ, Song DH. A Korean patient with Guillain-Barre syndrome following acute hepatitis E whose cholestasis resolved with steroid therapy. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2016;22(3):396–399. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2015.0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lei JH, Tian Y, Luo HY, Chen Z, Peng F. Guillain-Barre syndrome following acute co-super-infection of hepatitis E virus and cytomegalovirus in a chronic hepatitis B virus carrier. J Med Virol. 2017;89(2):368–372. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stevens O, Claeys KG, Poesen K, Saegeman V, Van Damme P. Diagnostic challenges and clinical characteristics of hepatitis E virus-associated Guillain-Barre syndrome. Jama Neurol. 2017;74(1):26–33. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Liver function after admission in our hospital. The patient’s liver function tests showed showed 20 μmol/L total bilirubin, 10 μmol/L conjugated bilirubin, 126 U/L alanine aminotransferase, and 160 U/L gamma-glutamyl transpepidase. (DOCX 16 kb)

Serologic studies for hepatitis virus. Serologic studies for IgM and IgG anti-HEV were both positive. No serological evidence was found for hepatitis A virus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, hepatitis D virus. (DOCX 15 kb)

Serological study for HBV, HCV, Syphilis and HIV. Serologic studies for hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, syphilis or human immunodeficiency virus was negative. (DOCX 15 kb)

Serological study for Epstein–Barr virus and cytomegalovirus. Epstein–Barr virus and cytomegalovirus serology indicated positive IgG. (DOCX 14 kb)

The first cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination showed 0/μL monocyte, 4.6 mmol/L glucose level, and 275.3 mg/dL protein level. (DOCX 15 kb)

The second cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination revealed 10/μL monocyte and 85.7 mg/dL protein level. (DOCX 15 kb)

Liver function (one month later after discharge). A month later, the liver function of the patient substantially improved, and his serum levels of AST and ALT were nearly normal. (DOCX 16 kb)

Serological study for HEV(six months later). Six months after discharge, serological study showed IgM anti-HEV antibodies became negative. (DOCX 15 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The data and materials are presented within Additional files 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8.