Summary

Spinal cord injury (SCI) medicine emerged after World War II due to mass casualties, which required specialized treatment centers. This approach to categorical care, however, was first developed during World War I, led by pioneers R. Tait McKenzie and George Deaver, who demonstrated that soldiers disabled by paralysis could return to society through fitness/mobility, recreational and vocational training. McKenzie, a Canadian and the first professor of physical therapy in the US, influenced Deaver and military physicians in Britain, Canada, and the U.S. with his achievements and publications.

Although early mortality from SCI was high, advances in the treatment of skin and bladder complications coupled with rehabilitation developed through lessons learned in World War I, resulted in major changes in survival and quality of life for veterans of World War II in England, US, and Canada. Harry Botterell and Al Jousse, founders of Lyndhurst Lodge, the first SCI center in Canada, adopted Deaver’s principles and techniques of rehabilitation and Donald Munro’s approach to medical complications. The consequences of failing to organize continuity of care in World War I were recognized both by consumers and physicians. Together with John Counsell, a World War II veteran, they formed the Canadian Paraplegic Association, which “revolutionized” the care of veterans with SCI, as well as civilians, women, and children.

Keywords: Spinal cord injury medicine, Military medicine, Rehabilitation, Peripheral nerve injury, World War I, World War II

Introduction

This article focuses on the career of R. Tait McKenzie and his pioneering role in military and rehabilitation medicine. His legacy to spinal cord injury (SCI) medicine can be traced to categorical care in World War I, his influence on George Deaver, and indirectly, on the first SCI center in Canada at Lyndhurst Lodge in Toronto.

McKenzie’s early contributions to the science of therapeutic exercise, sports and fitness, which was later applied to military and rehabilitation medicine in World War I, will be reviewed below, but has recently been reported in more detail.1,2

Military medicine has had a major influence on the development of SCI medicine and physical medicine and rehabilitation dating back to World War I. Although its origins in Europe and North America may have differed by location and specialty, the organization of categorical centers for the delivery of specialized services to soldiers with severe injuries, especially neurological injuries, had much in common. Patients were triaged according to their need for either routine care or specialized comprehensive care incorporating long-term medical and rehabilitation services. Peripheral nerve injuries in Germany, England, and the US, served as the model for categorical comprehensive care.3,4

While pioneers such as Sir Ludwig Guttmann,5 Harry Botterell and Albin Jousse, Donald Munro,6 Ernest Bors7 and Estin Comarr8 are well recognized for their contributions to the restoration of function in wounded soldiers during World War II, comparatively little recognition has been given to the origins of their comprehensive approach to SCI care.9 During World War I, Otfrid Foerster in Germany and Charles H. Frazier in the US reported on a large series of 3000 to 4000 cases of peripheral nerve injuries requiring restorative services of physical treatment, training, and vocational assessment.3,10,11

Sir Robert Jones from Great Britain is credited with the organization of special orthopedic centers, which provided integrated operative and restorative services. Jones placed R. Tait McKenzie, a Canadian citizen with the title of professor of physical therapy at an American university, in charge of inspecting the restorative care of the British centers.9 Accounts of McKenzie’s success in restoring the wounded to function with physical training were published in important British journals leading to increased recognition. Realizing that military physicians in World War I were unprepared for dealing with mass casualties requiring rehabilitation, he wrote the Handbook of Physical Therapy, which became the reference manual for the British, Canadian and US Armed Forces.2,11,12 In 1917, he was recognized by the Canadian government and invited to make recommendations to the Military Hospital Commission on the reeducation (rehabilitation) of wounded soldiers in regards to the staffing and equipment of Military Convalescent Hospitals from “Halifax to Victoria”.13 This article highlights the contributions of this great Canadian physician and his role in the origins of comprehensive rehabilitation.2,14,15

McKenzie’s education in Canada

James Naismith played an important role in McKenzie’s career. He served as a role model for excellence in sports, physical education and creative innovation of competitive indoor sports. McKenzie and Naismith were close boyhood friends, who played sports together and continued this relationship when they entered McGill University.16 While Naismith excelled in football, McKenzie won medals in track and field. It was Naismith, who assumed the responsibility of supervising gymnastic classes at McGill in 1889, and later asked McKenzie to share the teaching responsibilities. Shortly thereafter, Naismith would be recruited to Springfield College in Massachusetts by Luther H. Gullick, and together they would invent the game of basketball.17

McKenzie afterwards assumed full responsibility for teaching undergraduate gymnastics, thus launching his career in physical education.2 His interest in exercise and fitness continued following his entrance into medical school in the 1890s, where he embraced and taught the academic disciplines of anatomy and kinesiology. During summer vacations, he studied anthropometrics, the quantitative measurements of men and women’s response to exercise, under Paul Dudley Sargent.

McKenzie attended courses for 2 summers, in 1889 to 1890, on the theory of systems in physical education, anthropometry, applied anatomy, and other sciences, which were applied in class drills that involved exercises with weights, vaulting with bars and horses, tumbling, and dancing. Sargent’s systematic measurement of body proportions and research that involved thousands of male and female students and that included physiological studies of respiratory capacity and grip strength, established that training approaches must be scientifically based. This same scientific rigor is evident in McKenzie’s future cardiac studies.

Many of the machines used in gymnasiums throughout the United States, such as rowing, pulley systems for specific muscle groups, and lifting, were developed by Sargent. However, Sargent faced opposition to his scientific approaches to the study of physical conditioning by the conservative elements of academe. Yet, McKenzie predicted that Sargent’s place in the history of physical education would be as “pioneer, thinker, and scientist.”2

Sargent was not only a pioneer in regard to the role of gymnastics in medicine at Harvard, but founded a school of physical therapy in Boston, which was named in his honor and is one of the oldest in the US.18 McKenzie’s collaboration with Sargent, and his accompanying introduction to the scientific metrics of exercise in health and illness, defined McKenzie’s career interest for the next 40 years.

Gullick, who pioneered physical fitness for the YMCA at Springfield College, approached McKenzie following his graduation from medical school and attempted to recruit him to join himself and Naismith. Although McKenzie declined for personal reasons, the two became friends and colleagues, and both have been identified as pioneers in sports medicine.2 At Gullick’s request, McKenzie helped train directors for the YMCA in Montreal during those years.

Following his graduation from McGill University in 1892, McKenzie served as an intern/surgeon to the Marquis of Aberdeen, Governor of Montreal, and joined the faculty of the medical school in 1894. The previous year (1893), while serving as an instructor in gymnastics at McGill, he published his first medical article, “The Therapeutic Effects of Exercise,”19 in which he cites Hippocrates, Galen, and Sir William Osler as advocates of exercise for health in contrast to reliance on medications alone. McKenzie later reinforced this theme in the introduction to his textbook, Exercise in Education and Medicine, published in 1909.20

McKenzie’s academic career

In 1904, McKenzie was invited to join the faculty at the University of Pennsylvania. He sought the advice of fellow Canadian, Sir William Osler, who had served on the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania (1884–1889) after leaving McGill University (1874–1884) and before joining Johns Hopkins University (1889–1905). They had developed a cordial relationship over the years in Canada, the US, and later, in England during World War I. Based on this relationship, McKenzie would be commissioned by the Historical Society of Johns Hopkins to create a memorial plaque of Osler in 1925.21

Encouraged by Osler, McKenzie accepted the unique academic opportunity from the University of Pennsylvania and served as professor of physical education and professor of physical therapy (physical medicine and rehabilitation) from 1904 until 1930.22 Most chairs/professors at the University of Pennsylvania authored textbooks unique to their specialty at the time. This is when McKenzie wrote Exercise in Education and Medicine,20 which is likely the first textbook on therapeutic exercise in the US. He appreciated the need for accurate diagnoses to enable physicians to prescribe specific exercises to restore function. Based on his familiarity with the work of Frenkel in neurological disorders, he defined the physical training approach for individuals with impaired balance in which footsteps are painted on the floor, enabling individuals to practice specific patterns of foot placement until improvement in walking is noted.20

As a strong advocate of fitness and sports, he initiated a program of mandatory medical examination for the students at the University of Pennsylvania, with recommendations for remedial exercises. He taught the principles of physical medicine and rehabilitation to sophomore and junior medical students in the classroom, and to seniors during clinical rotations. This was likely the first effort in a North American medical school to systematically expose students to the scientific benefit of physical treatment and exercise, predating the efforts of John Stanley Coulter23 and Frank Krusen by 20 years.

In the introduction to his most cited scientific publication, Exercise in Education and Medicine, he chides organized medicine at the time for its reliance on medication to the exclusion of exercise in medical education and practice.

Exercise and massage have been used as remedial agencies since the days of Aesculapius, but definite instruction in their use has seldom been given to medical students. Perhaps a certain laziness which is inherent in both patient and physician tempts to the administration of a pill or draught to purge the system of what should be used in normal muscular activity, but there is a wide dearth of knowledge among the [medical] profession of the scope and application of exercise in pathologic conditions, and the necessity of care in the choice and accuracy of the dosage will be emphasized throughout the second part of this book.20

We will find these sentiments echoed 40 years later in the writings of pioneers in physical medicine and rehabilitation, John Stanley Coulter, Frank Krusen and George Deaver.24–26

Lessons of the First World War

One of the legacies of World War I, which inspired pioneers of SCI medicine, was the founding of categorical peripheral nerve injury (PNI) centers.4 Charles H. Frazier, professor of neurosurgery at the University of Pennsylvania who trained Donald Munro (1916), was credited with the establishment of the first PNI treatment facility in the US in 1918, which coordinated specialized care, rehabilitation and research.10,11

In the United Kingdom, Sir Robert Jones developed the concept of Military Orthopedic Centres, with coordinated specialized care and rehabilitation. Military appointments of neurologists and electrotherapists sharpened clinical diagnoses and examinations. Surgical techniques were introduced, then discarded or accepted as surgeons developed skills to meet the new conditions. The US Surgeon General, William Gorgas, and his consultant in neurosurgery, Charles Frazier, went a step further, with the organization of a research laboratory, as well as the establishment of a Peripheral Nerve Commission and Registry.11

R. Tait McKenzie joined the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania in 1904 during Frazier’s tenure as dean of the medical school (1901–1910). They knew each other well professionally and socially, and influenced each other in the rehabilitation of injuries to the neurological system. McKenzie sculpted bas reliefs of Frazier’s son and daughter as children in 1906.27 Recently, Frazier and McKenzie were paired together “as Americans” in a history of “military medical care for peripheral nerve injuries during World War I”,11 since both worked in reconstruction hospitals, Frazier in the US and McKenzie (Figure 1) in the UK under Sir Robert Jones. It was McKenzie’s Handbook of Physical Therapy (Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation) that was used by physicians in the American, British, and Canadian armed forces in World War I.2,11

Figure 1.

Major McKenzie at Heaton Park Depot, England 1915. From the University Archives and Records Center, University of Pennsylvania.

Lessons learned in World War I about peripheral nerve injuries were lost, however, due to inadequate follow up and metrics for the course of recovery. The manual muscle test (MMT), developed by Lovett in 1917 for determining the course of recovery and treatment for poliomyelitis,1 would not be introduced into military medicine until World War II, based on the Medical Research Council Memorandum in 1942.28 McKenzie, likely unaware of Lovett’s contribution in 1917, recommended graded strengthening exercises in his article on nerve and muscle injuries, which include isometric contraction of the limb in a splint, to be progressed as strength returned to functional activities.29 He instructed that precise measurement of strength, range of motion, dosage of exercise be recorded and substitution patterns of muscle action be avoided.

ACTIVE MOVEMENT

Active movements may be free, but as a muscle works better against a certain amount of resistance, apparatus is necessary to measure the amount of work done and the distance -the load is raised. Free movements are merely a rehearsal of the motions

of which a joint is capable and need not be described in detail, but even if a limb is fixed by a splint, muscles can be twitched by the patient and so receive a certain amount of exercise, without any active movement taking place in the joints involved.

Most appliances for giving exercise are cumbrous and expensive, and it has been our endeavor to design machines that would fulfill the following conditions:

1. To isolate the movement and so prevent the mistaken idea of improvement when it is really another group that is doing the work.

2. To record the range of movement, so that both patient and the operator can follow the progress of improvement.

3. To measure the dose of work in terms of the number of contractions and weight raised.30

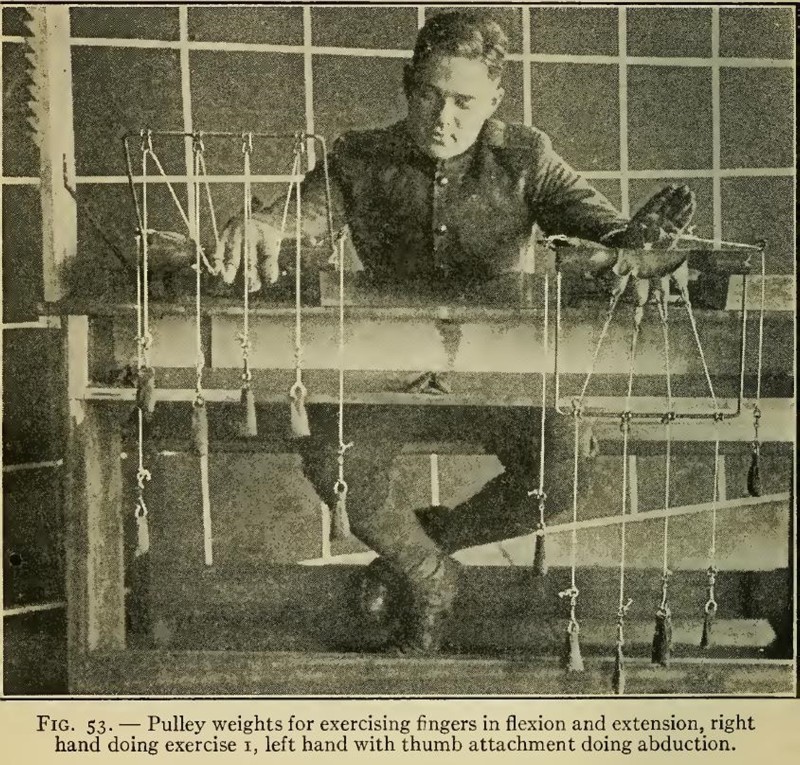

McKenzie provides illustrations of the various devices and equipment used to rehabilitate disabled soldiers at Heaton Park Depot, England in his Handbook of Physical Therapy (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Graded exercises with pulleys and weights to strengthen weaken muscle due to nerve injury.12

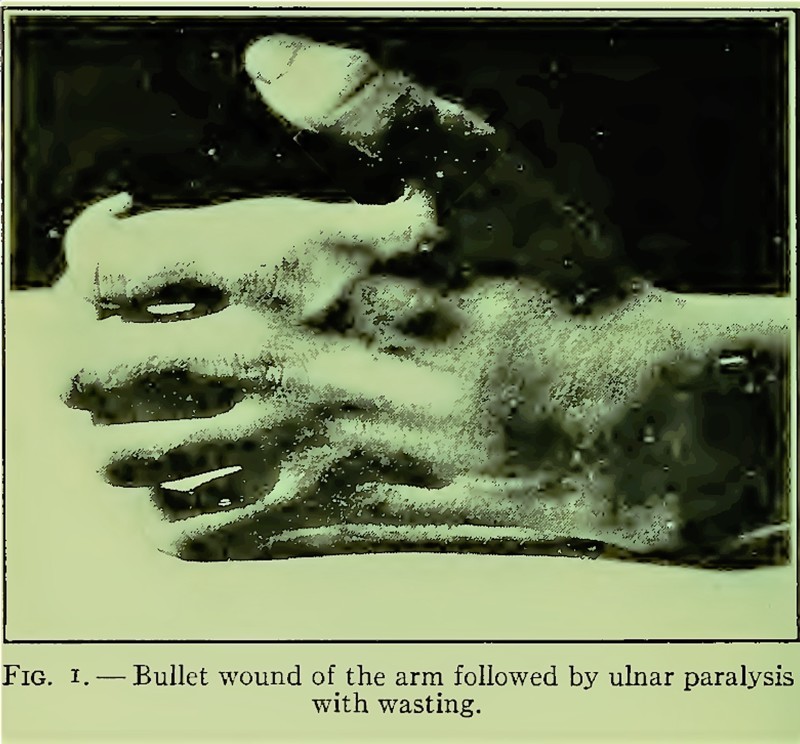

Figure 3.

Ulnar nerve injury.12

After he returned to the US in 1917, McKenzie was invited to Canada to advise the Canadian Government and the Military Hospital Commission. In an editorial published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal13 entitled “The Physical Education [Rehabilitation] of Disabled Soldiers”, he requested a survey of Canadian Military Convalescent Hospitals and recommended standardization so “that hospitals from Halifax to Victoria will soon have workers and equipment.”

Guttmann, who worked for years on peripheral nerve injuries, cited the categorical approach of specialized care and rehabilitation pioneered by Jones, Frazier and his mentor Foerster in 1942,31 Silver attributes Guttmann’s experience with peripheral nerve injuries as the inspiration for Guttmann’s later development of the famed Spinal Cord Injury Center at Stoke Mandeville Hospital in Aylesbury, England in 1944.4,9

World War II and SCI Care in Canada

The role of Harry Botterell and Al Jousse (Figures 4 and 5) in the founding of SCI medicine in Canada is appreciated in most historical works on this topic.9,32,33 Although, Botterell demonstrated an interest in the comprehensive care of persons with SCI as early as the 1930s, it was not until after the war, in the spring of 1945, that he was confronted with the challenge of several hundred veterans requiring his positive attitude and concept of coordinated medical and rehabilitative care.34,35 Within 18 months, he and his colleague, Jousse, published their first report of their approach and experience.36 In this report, the studies of Munro and Deaver are cited as the basis for the development of SCI medicine and treatment centers in Canada:36

The work to be presented has developed from that of Munro and Deaver and Brown.

During the summer of 1945 some 200 paraplegic patients were gathered into four centres strategically placed across Canada. During the period from February 3, 1945 to June 1, 1946, 103 post-traumatic paraplegic patients from the Armed Forces have been treated in Christie St. Hospital and Lyndhurst Lodge, Toronto.36

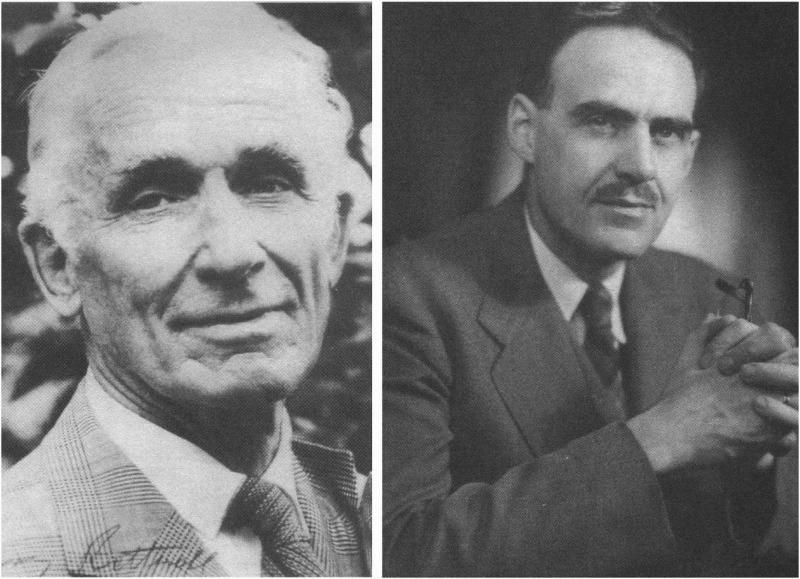

Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Harry Botterell (left) and Al Jousse (right), founders of Lyndhurst Lodge. Photos courtesy of Dr. William Geisler and the G. Kenneth Langford, Sr. Family, respectively.

We may trace the origins of the Lyndhurst Center concept of rehabilitation to R. Tait McKenzie. McKenzie had a direct impact on George Deaver during the First World War, and an indirect one on Donald Munro during Munro’s neurosurgical training in Philadelphia under Charles H. Frazier. Deaver was a medical student (1915–1918) at the University of Pennsylvania, taught by McKenzie, who was professor of physical medicine (physical therapy) and professor of physical education.2 Before medical school, Deaver had been immersed in physical education at Springfield College in Massachusetts, and served with the YMCA Expeditionary Force in World War I (1918–1920), where he rehabilitated thousands of US and British soldiers with physical therapy, occupational therapy, gymnastics and sports.38,39

Figure 6.

George G. Deaver.37 Image courtesy of The Lillian and Clarence de la Chapelle Medical Archives of NYU.

McKenzie and Deaver (Figure 6) published back-to-back articles of their war experiences in the YMCA journal.40,41 Following the war, Deaver continued with the YMCA until 1930, when he was recruited by John Stanley Coulter to join Northwestern University School of Physical Therapy.2 Deaver (Figure 7) later moved to New York City, where he worked at the Hospital for the Crippled and Disabled, from 1935 to 1945. During this time, he developed the classical metric, “Activities of Daily Living (ADL)”, which documented gains achieved through rehabilitation, and remains the standard today.38,42

Figure 7.

Deaver passport photo, 1918.39

Dr. Jousse was appointed medical director at Lyndhurst Lodge (1945–1975) in March of 1945. He immediately visited with Deaver for several months, after reading his publications on crutch walking.35,43

“Between April and June 1945, Jousse travelled to the Institute for the Care of the Crippled in New York City to observe the work of Dr. Deaver, a leading proponent of crutch walking.”35

Munro’s residency training under Frazier exposed him to the concepts of rehabilitation. Frazier’s recognition of the importance of physical treatment in the restoration of function after peripheral nerve injuries sustained during World War I is reflected by his specific mention of massage, electrical stimulation and graded exercises.10

“The after-treatment is a matter of vital consideration; massage, galvanism and later faradism, properly selected exercises, these must be continued faithfully and persistently until voluntary movement has returned.”10

Munro also had inherited one of the finest departments of physical medicine and rehabilitation at Boston City Hospital in 1929, which had been founded by another pioneer physiatrist, Frank B. Granger (head of physical therapeutics, 1907–1928). Granger had been in charge of physical therapy (physical medicine) for the US Army at Walter Reed Hospital during World War I, and was a nationally recognized expert.24,44 Although, Munro never cited McKenzie, Frazier, or Granger, his training reflected the tradition of the categorical treatment of PNI centers founded by Frazier to include comprehensive rehabilitation and vocational retraining of veterans of World War I.

Jousse credits Botterell with creating the environment of a team approach to acute and long-term care for SCI. In his article on the evolution of the treatment program for paraplegia in Canada,34 Jousse emphasizes the need for one physician, a specialist in physical medicine and rehabilitation, to be involved as consultant to the surgeons in the acute hospital phase and to assume total care of the patient through rehabilitation and life-long follow up.

Although the tradition of McKenzie, Deaver, Munro and later, Bors and Comarr, would influence future SCI rehabilitation physicians in the US, particularly in the Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals, the Canadian model developed by Botterell, Jousse and later, William Geisler, surpassed the US in scope of services for all age groups, genders, veterans, and civilians.9 In Tremblay’s excellent history of the “Canadian revolution of the management of SCI”, she credits the trio of Botterell, Jousse and John Counsell for this incredible achievement.35 Together they established the Canadian Paraplegic Association (CPA), which negotiated services for civilians, as well as veterans.

Lessons Learned

A major lesson from World War I was that the expert comprehensive centers established in the US and Canada in response to the crisis of large number of severely injured soldiers disappeared due to a failure to anticipate future needs.11 The CPA foresaw that following the Second World War, veteran admissions to Lyndhurst Lodge and staffing would decline, but new civilian admissions would justify continuation of the program.30 McKenzie’s impact on the Military Hospital Commission in Canada is never mentioned in historical reviews, and Frazier’s peripheral nerve clinical and research centers lacked qualified physicians to report on recovery of injury and rehabilitation following World War I.11 Disability historians, who accurately reflect the consumer’s perspective of rehabilitation services during and after the War, rather than the glamorized image of the “supercrip” in World War I and the impressive reduction of mortality in World War II, keep us focused on future needs.30,45 Counsell, and the countless veterans and consumers who have benefitted from the SCI rehabilitation center, have helped preserve this attitude of the need to do better.30

The pioneers of Lyndhurst Lodge published their results of 30 years of experience in their SCI center and concluded:

1. Substantial as is the merit of the existing care, province wide, of patients with acute cord injury, there is great need for development of an improved system of total management of patients with acute spinal cord injuries, and for prevention of spinal injuries.

2. A new model is needed for the care of acute cord injuries.46

They listed 13 characteristics that included defining regional SCI centers for acute and rehabilitation services, staffing by experts affiliated with university hospitals, delivering patient-centered medical care, using modern methods of communication, and transporting patients to regional centers rather than local hospitals.

Conclusion

War creates mass casualties with loss of function due to injuries to the nervous system requiring long-term rehabilitation services. Military medicine responded to these challenges in World War I by developing categorical treatment centers for peripheral nerve injuries, which were well organized in Germany, England and North America. This model provided guidance for the development of similar services for SCI in World War II. Revolutionary gains in survival, functional restoration, and return to a fuller life were made possible with advances in medicine/surgery and the pioneering efforts of physicians and consumers motivated to restore life with meaning. The lessons learned from World War I regarding failure to provide continuing systematic care resulted in veterans’ programs led by consumers, who have identified their needs and aspirations. In North America, the Canadian model has led the effort in providing comprehensive long-term care for persons with SCI that includes civilians, women, and children, in addition to veterans.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks William Geisler, John R. Silver and Cathy Craven for helpful suggestions.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors None.

Funding None.

Declaration of interest None.

Conflicts of interest None.

Ethics approval None.

References

- 1.Ditunno JF Jr, Verville RE. Bennett Robert L. Dr.: Pioneer and definer of modern physiatry. PM R 2013;5:83–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ditunno JF Jr, Verville RE. Tait McKenzie R. Dr.: Pioneer and legacy to physiatry. PM R 2014;6:866–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zulch KJ. Otfrid Foerster, Physician and Naturalist. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag, 1969, p.96. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiner MF,Silver JR.. The origins of the treatment of traumatic spinal injuries. Eur Neurol 2014;72:363–9. Available at: https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/365287 Accessed March 26, 2017. doi: 10.1159/000365287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guttmann L. Rehabilitation after injuries to the spinal cord and cauda equina. Br J Phys Med 1946;9:130–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bodner DR. A pioneer in optimism: the legacy of Donald Munro, MD. J Spinal Cord Med 2009;32(4):355–6. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2009.11754510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodner DR. The Bors Award: Legacy of Ernest H. J. “Pappy” Bors, MD. J Spinal Cord Med 2009;32(1):1–2. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2009.11760746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodner DR. The Comarr Memorial Award for Distinguished Clinical Service: The legacy of A. Estin Comarr, MD. J Spinal Cord Med 2009;32(3):213–4. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2009.11760775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silver JR. History of the Treatment of Spinal Injuries. New York, Kluwer Academic/ Plenum Publishers, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frazier CH. Surgical problems in the reconstruction of peripheral nerve injuries. Ann Surg 1920;71:1–10. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1410460/ Accessed March 26, 2017. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanigan W. The development of military medical care for peripheral nerve injuries during World War I. Neurosurg Focus 2010;28:E24. doi: 10.3171/2010.3.FOCUS103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKenzie RT. Reclaiming the Maimed: A Handbook of Physical Therapy. New York: Macmillan, 1918. Available at: https://archive.org/details/recaimingmaimed00mcke Accessed March 29, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13.The physical reeducation of disabled soldiers. Can Med Assoc J. 1917;7:1099–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wrynn AM. “Under the showers”: An analysis of the historical connections between American athletic training and physical education. J Sport Hist 2007;34:37–52. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mason F. Sculpting soldiers and reclaiming the maimed: R. Tait McKenzie’s work in the First World War period. Can Bull Med Hist 2010;27:363–83. doi: 10.3138/cbmh.27.2.363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKenzie RT. Reminiscences of James Naismith. J Health Phys Educ 1933;4:21–55. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naismith JG, Gullick L.. Basketball: A book written by Dr. James Naismith and Dr. Luther Gullick, 1894. Springfield, Mass: American Sports Publishing Company, 1894, p.35 Available at: http://cdm16122.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15370coll2/id/344 Accessed March 26, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dudley Allen Sargent: An Autobiography. Lea & Febiger, 1927, p.221.

- 19.McKenzie RT. The therapeutic uses of exercise. Montreal Med J 1894;22:561–72. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKenzie RT. Exercise in Education and Medicine. Philadelphia. London: WB Saunders Co, 1909, p.556 Available at: https://archive.org/details/exerciseineducat01mcke Accessed March 26, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stone MJ. William Osler’s legacy and his contribution to haematology. Br J Haematol 2003;123:3–18. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04615.x/full Accessed March 26, 2017. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04615.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Packard CSW. (Letter) C. S. W. Packard to R. Tait McKenzie. Philadelphia, PA, 1904. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ditunno JF Jr, Sandel ME.. John Stanley Coulter, MD, and the emergence of physical medicine and rehabilitation in the early 20th century. PM R. 2016;9:193–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2016.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coulter JS. History and development of physical medicine. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1947;28:600–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krusen FH. History and development of physical medicine. Clinics 1946;4:1343–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deaver GG. Physical rehabilitation of disabled persons. N Engl J Med. 1947. Feb 27;236(9):311–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM194702272360902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKenzie RT. R. Tait McKenzie papers. Collection UPT 50 McK37. Available at: http://www.archives.upenn.edu/faids/upt/upt50/mckenzie_rt.html Accessed March 26, 2017.

- 28.Riddoch G. Aids to the Investigation of Peripheral Nervous System. War Memorandum Number 7. Medical Research Council: Nerve Injuries Research Committee. Great Britain: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1942. Available at: https://www.mrc.ac.uk/documents/pdf/aids-to-the-examination-of-the-peripheral-nervous-system-mrc-memorandum-no-45-superseding-war-memorandum-no-7/ Accessed March 26, 2017.

- 29.McKenzie RT. The treatment of nerve, muscle, and joint injuries in soldiers by physical means. Can Med Assoc J 1917;7:1057–68. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1584984/ Accessed March 26, 2017. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reaume G, Lyndhurst: Canada’s First Rehabilitation Centre for People with Spinal Cord Injuries. 1945–1998 Montreal, Canada: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rehabilitation after injuries to the central nervous system: (Section of Neurology) Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1942;35:295–308. Accessed 3/26/2017 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1998156/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guttmann L. Spinal Cord Injuries: Comprehensive Management and Research. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Science Ltd; 1973, p.712. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohry A, El Masri W.. Spinal cord injury management: historical perspective. In: Chhabra H, S., (ed.). ISCoS Textbook on Comprehensive Management of Spinal Cord Injuries. 1st ed Philadelphia PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2015, p. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jousse AJ. The evolution of the treatment programme for paraplegics in Canada. J Assoc Phys Ment Rehabil 1962;16:Sep-Oct;16:131–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tremblay M. The Canadian revolution in the management of spinal cord injury. Can Bull Med Hist 1995; 12:125–55. Available at: http://www.cbmh.ca/index.php/cbmh/article/viewFile/353/352 Accessed March 26, 2017. doi: 10.3138/cbmh.12.1.125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Botterell EH, Jousse AT, Aberhart C, Cluff JW.. Paraplegia following war. Can Med Assoc J 1946;55:249–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.George G. Deaver (photo). US National Library of Medicine. New York City: New York University College of Medicine, 1950. Available at https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-101413425-img Accessed March 28. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flanagan SR, Diller L. Deaver George Dr.: the grandfather of rehabilitation medicine. PM R 2013;5:355–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.03.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deaver George Gilbert, Dr., US Passport Application 1915–1920 Vol. 001: Egypt.

- 40.Deaver GG. Physical training of the wounded in Egypt. Physical Training 1919; XVI: 5. [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKenzie RT. The place of the physical director in the rehabilitation of the wounded. Physical Training 1919; XVI: 4. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deaver GG, Brown ME.. No. 1. Physical demands of daily life: An objective scale for rating the orthopedically exceptional. New York: Institute for the Crippled and Disabled, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deaver GG, Brown ME.. The challenge of crutches; prescribing crutch gaits for orthopedic disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1945;26:747–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vogel EE. Physical therapists before World War II (1917–40). In: Anderson E, (ed.). Army Medical Specialist. Corps. Washington, DC: US Army Medical Department Office of Medical History, 1968. Available at http://history.amedd.army.mil/corps/medical_spec/chapterIII.html Accessed March 26, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Linker B. War’s Waste: Rehabilitation in World War I America. London, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2011, p. 291. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Botterell EH, Jousse AT, Kraus AS, Thompson MG, WynneJones M, Geisler WO.. A model for the future care of acute spinal cord injuries. Can J Neurol Sci 1975;2:361–80. doi: 10.1017/S0317167100020497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]