Abstract

Background

The ACCOMPLISH (Avoiding Cardiovascular Events Through Combination Therapy in Patients Living with Systolic Hypertension) trial demonstrated that combination therapy using amlodipine, rather than hydrochlorothiazide, in conjunction with benazepril provided greater cardiovascular risk reduction among high‐risk hypertensive patients. Few trials have evaluated the effect of prior antihypertensive therapy used among participants on the study outcomes.

Methods and Results

In a post hoc observational analysis, we examined the characteristics of the drug regimens taken before trial enrollment in the context of the primary composite outcome (death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, hospitalization for angina, resuscitation after sudden cardiac death, and coronary revascularization). In the “primary subgroup” (n=4475), patients previously taking any renin‐angiotensin system blockade plus either a diuretic or a calcium channel blocker alone or as part of their antihypertensive regimen, there were 206 of 2193 (9.4%) versus 281 of 2282 (12.3%) primary composite events among those randomized to combination therapy involving amlodipine versus hydrochlorothiazide, respectively (adjusted Cox proportional hazard ratio, 0.74; 95% confidence interval, 0.62–0.89; P=0.0015). All other participants (n=6975) previously taking any antihypertensive regimen not included in the primary subgroup also benefited from randomization to amlodipine plus benazepril (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.72–0.98; P=0.024). Outcomes among most other subgroups, including patients previously taking lipid‐lowering medications or dichotomized by prior blood pressure control status, showed similar results.

Conclusions

When combined with an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor, amlodipine provides cardiovascular risk reduction superior to hydrochlorothiazide, largely regardless of prior medication use. These findings add further support for the initial use of this combination regimen among high‐risk hypertensive patients.

Keywords: blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, risk, therapy

Subject Categories: Hypertension, Treatment, Clinical Studies

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

When combined with an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor, amlodipine provided superior cardiovascular risk protection compared with hydrochlorothiazide, irrespective of what blood pressure–lowering agents were used in the past.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Because most hypertensive patients (≥75%) require ≥2 medications to achieve blood pressure goals, our observations support that most patients should consider treatment with a renin‐angiotensin system blocker combined with a calcium channel blocker as first‐line therapy or as part of the overall therapeutic regimen (if additional drugs are still required), even if other antihypertensive agent(s) were used in the past.

A streamlined strategy of starting initial combination therapy using a renin‐angiotensin system blocker combined with a calcium channel blocker should be tested versus current hypertension guidelines in a clinical outcome trial for the prevention of cardiovascular events.

Introduction

Antihypertensive therapy is well established to reduce the adverse cardiovascular consequences of high blood pressure (BP).1 The overall evidence supports that the degree of BP lowering is the major determinant of the health benefits.1 Guidelines, therefore, emphasize the importance of controlling BP as the preeminent goal.2, 3 In this regard, it is important to acknowledge that most hypertensive patients (eg, 75%) require ≥2 antihypertensive medications to achieve BP targets.4 As such, the most germane issue to explore in guiding present‐day clinical practice is which combination of medications (rather than what single agent) provides optimal cardiovascular protection.5 Although most patients in clinical trials were taking >1 antihypertensive medication,1 only the ACCOMPLISH (Avoiding Cardiovascular Events Through Combination Therapy in Patients Living with Systolic Hypertension) trial was designed to investigate the comparative cardiovascular risk reductions derived from 2 prespecified combination regimens prescribed as initial therapy.6 The study was terminated early (mean follow‐up, 36 months) because of the superiority of benazepril+amlodipine compared with benazepril+hydrochlorothiazide for preventing the primary composite outcome (hazard ratio [HR], 0.80; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.72–0.90; P<0.001). Subsequent analyses showed that this benefit occurred among patients with coronary artery disease7 and diabetes mellitus,8 was superior for preventing adverse renal outcomes,9 and was not likely a consequence of subtle BP differences between groups (ambulatory BP monitoring).10

As with most contemporary trials,1 most patients (97.1%) entering into the ACCOMPLISH trial had already been receiving antihypertensive therapy.6 Hence, the main conclusion of the study can most accurately be stated as follows: switching treated hypertensive individuals to initial combination therapy composed of benazepril+amlodipine rather than benazepril+hydrochlorothiazide is more effective for preventing cardiovascular events. Because of this high rate of background therapies, it is important to evaluate if the characteristics of the prior regimens had a modifying effect on study outcomes. For example, some medication(s) may have differed in reducing baseline cardiovascular risk (eg, superior 24‐hour BP control and fewer adverse metabolic actions) and could have, thereby, plausibly affected the capacity for the ensuing randomized treatments to differentially provide cardiovascular protection. The principal aim of this post hoc observational analysis was to determine if combination therapy using benazepril+amlodipine conveys a significant risk reduction on the primary composite end point in a subgroup of patients who had already been taking a drug regimen similar to either of the treatment limbs allocated in the trial (“primary subgroup”): renin‐angiotensin system (RAS) blockade plus either a thiazide‐type diuretic or any calcium channel blocker (CCB) alone or as part of their antihypertensive regimen. This is a clinically relevant question because both combination therapy regimens remain recommended approaches by guidelines2, 3 and are considered rational pharmacological strategies4 commonly used in present‐day practice. In secondary analyses, we explored if prior use of other antihypertensive regimens, background lipid‐lowering therapy, or previous BP control status may have modified the benefits derived from allocation to benazepril+amlodipine.

Methods

The overall design and methods of the ACCOMPLISH trial have been previously described.6 The institutional review boards or ethics committees of each participating site approved the protocol, as described in the primary article.6 The data, analytic methods, and study materials will not be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure. In brief, the ACCOMPLISH trial was an international (5 countries), multicenter (n=548), double‐blind, randomized, clinical outcome trial of 11 056 patients with hypertension at high risk for cardiovascular disease. The primary outcome was time to first composite event (death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, hospitalization for angina, resuscitation after sudden cardiac death, and coronary revascularization) compared between treatment limbs (benazepril+amlodipine versus benazepril+hydrochlorothiazide). In this post hoc observational analysis, we aimed to evaluate the effect of prior medication regimens on the primary study outcome. Before undertaking the analyses, we a priori defined the primary subgroup as patients previously taking a regimen similar to either randomized treatment subsequently allocated in the trial. This included individuals taking an RAS blocker (any angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor [ACEI] or angiotensin receptor blocker) plus either a thiazide‐like diuretic or CCB. The 2 antihypertensive medications could be taken alone (ie, no additional BP medications) or as part of a larger regimen (≥3 drugs in total), including any supplementary BP‐lowering medications (eg, β or α blockers). We began the series of analyses with and highlighted the presentation of our findings in this primary subgroup because we believed the results from these patients would yield the overall most clinically relevant information. These findings specifically inform healthcare providers the sum benefits together of maintaining an RAS blocker/CCB regimen if already taking it and switching to this regimen among patients taking an RAS blocker/diuretic regimen. Subsequent analyses further evaluated the individual benefits in each of these subgroups alone, along with several other groups with a viable sample size.

Statistical Analyses

The HRs and corresponding 95% CIs related to allocation to benazepril+amlodipine versus benazepril+hydrochlorothiazide were assessed among individual subgroups of participants previously treated with various antihypertensive and other medication regimens on entering the trial using survival analyses with Cox proportional hazard models. Specifically, the Cox models comparing the effectiveness of randomized treatments were separately evaluated in each of the specified subgroups of participants. The HRs in the Cox models were adjusted for baseline age, smoking status, history of myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, hospitalization for unstable angina, baseline systolic and diastolic BP levels, and left ventricular hypertrophy by ECG (covariables related to the primary end point). All other subgroups evaluated were analyzed as secondary end points by adjusted Cox proportional hazard models and confined to groups >700 patients because smaller sample sizes could yield unstable or unreliable results. Kaplan‐Meier estimates with the log‐rank test were also used to estimate and compare the end points throughout the trial for the 2 treatment groups. In addition to performing individual subgroup analyses, we also tested for effect modification on the HRs (by prior treatment subgroup identifier) in the entire cohort of patients. This was done by adding an interaction term of the subgroup indicator and treatment indicator in the Cox model that included all study participants.

Results

The characteristics of the overall ACCOMPLISH trial cohort (n=11 506) have been previously described.6 Table 1 presents the results separated into 2 subgroups: the primary subgroup (n=4475) versus “all other participants” (n=6975 individuals not receiving a regimen containing an RAS blocker plus either a diuretic or CCB on enrollment). There were 56 participants not taking any BP medication on enrollment into the trial who were not included in our current study, giving us a total sample size of 11 450. There were some small, but statistically significant, differences in characteristics between subgroups. However, this is not relevant in regard to the objectives of this study, which aimed to assess the efficacy of benazepril+amlodipine in both groups, irrespective of potential differences in characteristics.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Participants in the Main Subgroups (Total N=11 450)

| Subject Characteristics | Primary Subgroup | All Other Participants | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects, n (%) | 4475 (39.1) | 6975 (60.9) | … |

| Sex, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| Male | 2686 (60.0) | 4256 (61.0) | |

| Female | 1789 (40.0) | 2719 (39.0) | |

| Age, mean±SD, y | 68.2±6.9 | 68.4±6.9 | 0.102 |

| ≥65 y, n (%) | 2948 (65.9) | 4652 (66.7) | 0.366 |

| ≥70 y, n (%) | 1812 (40.5) | 2864 (41.1) | 0.545 |

| Race or ethnic group, n (%) | 0.081 | ||

| Black | 615 (13.7) | 757 (10.9) | <0.0001 |

| White | 3682 (82.3) | 5919 (84.9) | 0.0003 |

| Hispanic | 237 (5.3) | 385 (5.5) | 0.607 |

| Other | 164 (3.7) | 264 (3.8) | 0.741 |

| Region, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| United States | 3288 (73.5) | 4809 (69.0) | |

| Nordic countries | 1187 (26.5) | 2166 (31.0) | |

| Anthropometrics, mean±SD | |||

| Weight, kg | 89.8±18.9 | 87.8±19.0 | <0.0001 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 104.7±15.3 | 103.3±15.3 | <0.0001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 31.4±6.2 | 30.6±6.2 | <0.0001 |

| Medications, n (%) | |||

| Lipid‐lowering agents | 3933 (68.4) | 4662 (67.6) | 0.359 |

| β Blockers | 1930 (43.5) | 3451 (50.1) | <0.0001 |

| Antiplatelet agents | 2794 (63.0) | 4374 (63.5) | 0.641 |

| Hemodynamics, mean±SD | |||

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 144.8±18.1 | 145.8±18.4 | 0.007 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 79.3±10.7 | 80.5±10.7 | <0.0001 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 70.7±10.9 | 70.2±11.0 | 0.026 |

| Laboratory values, mean±SD | |||

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.0±0.28 | 0.98±0.26 | 0.0006 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 128.6±45.5 | 126.6±46.9 | 0.033 |

| Potassium, mmol/dL | 4.2±0.4 | 4.3±0.4 | <0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 183.4±38.9 | 185.1±40.1 | 0.046 |

| HDL‐C, mg/dL | 49.3±13.9 | 49.5±14.1 | 0.401 |

| Risk factors, n (%) | |||

| Myocardial infarction | 948 (21.2) | 1755 (25.2) | <0.0001 |

| Stroke | 565 (12.6) | 928 (13.3) | 0.293 |

| Hospitalization for United States | 475 (10.6) | 848 (12.2) | 0.012 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2897 (64.7) | 4007 (57.5) | <0.0001 |

| Renal disease | 319 (7.1) | 383 (5.5) | 0.0004 |

| Coronary revascularization, n (%) | 1495 (33.4) | 2612 (37.5) | <0.0001 |

| CABG | 869 (19.4) | 1570 (22.5) | <0.0001 |

| PCI | 814 (18.2) | 1359 (19.5) | 0.085 |

| Other, n (%) | |||

| LVH | 573 (13.1) | 954 (14.0) | 0.172 |

| Current smoking | 492 (11.0) | 803 (11.5) | 0.393 |

| Dyslipidemia | 3373 (75.4) | 5160 (74.0) | 0.094 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 297 (6.6) | 479 (6.0) | 0.632 |

BP indicates blood pressure; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; and PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

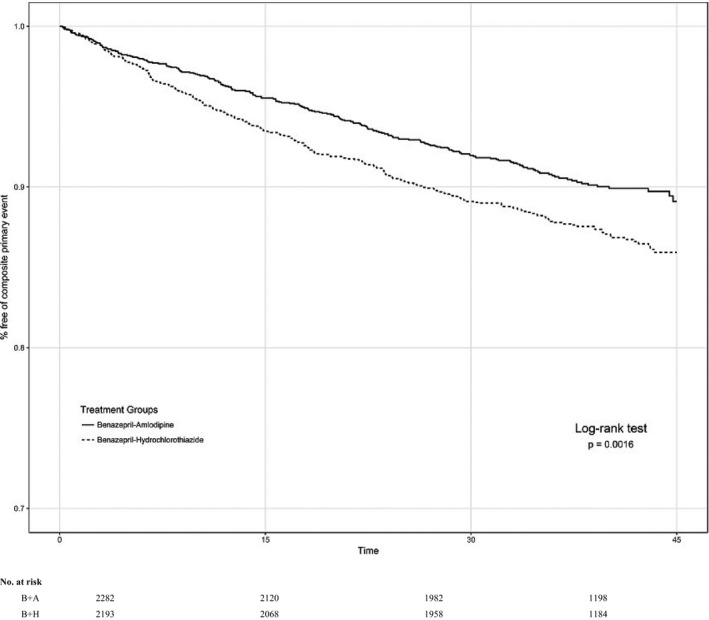

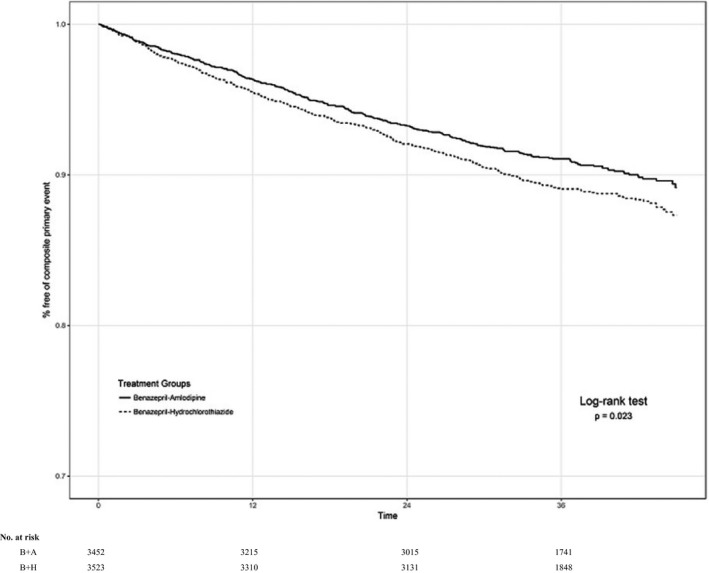

The following results are from the individual subgroup analyses. In the primary subgroup, there were 206 of 2193 (9.4%) composite study events among individuals randomized to benazepril+amlodipine versus 281 of 2282 (12.3%) among those allocated to benazepril+hydrochlorothiazide (adjusted HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.62–0.89; P=0.0015) (Figure 1). In all other participant subgroups, those assigned to benazepril+amlodipine (adjusted HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.72–0.98; P=0.024) also benefited (Figure 2). Confining the analyses to a “limited primary subgroup,” including individuals previously taking a 2‐drug regimen consisting of only an RAS blocker plus either a thiazide‐like diuretic or CCB (ie, no additional antihypertensive agent of any class in their regimen), yielded similar results. In this limited primary subgroup (n=2266), there were 97 of 1140 (8.5%) composite study events among individuals randomized to benazepril+amlodipine versus 117 of 1126 (10.4%) among those allocated to benazepril+hydrochlorothiazide (adjusted HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.61–1.04; P=0.099). Given the similar HR to that of the primary subgroup, the borderline nonsignificant P value is likely attributable to a smaller sample size. All other participants not in the limited primary subgroup (n=9184) also benefited from assignment to benazepril+amlodipine (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.70–0.91; P=0.0006). Controlling for achieved BP levels at 6 months into the trial did not substantively alter the results for any of the previously described subgroups.

Figure 1.

Composite trial outcomes in the primary subgroup. Survival curves among individuals in the primary subgroup: previously taking an antihypertensive regimen consisting of any renin‐angiotensin system blocker (angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker) plus (either a diuretic or calcium channel blocker) as part of their antihypertensive regimen who were randomized to benazepril (B)+amlodipine (A) (solid line) vs B+hydrochlorothiazide (H) (broken line). P value is for hazard ratio by log‐rank test.

Figure 2.

Composite trial outcomes among all other participants not in the primary subgroup. Survival curves among all other individuals not in the primary subgroup who were randomized to benazepril (B)+amlodipine (A) (solid line) vs B+hydrochlorothiazide (H) (broken line). P value is for hazard ratio by log‐rank test.

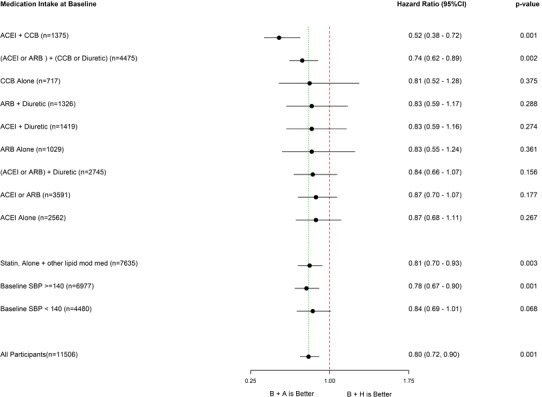

Although not always statistically significant, the HRs also favored randomization to benazepril+amlodipine for most other subgroups in secondary analyses on the basis of preenrollment or background drug regimens, including those taking lipid‐lowering medications or with a systolic BP of <140 mm Hg on study enrollment (Figure 3). With 1 exception (ACEI+CCB), the rates of the main composite end points were similar across subgroups within the same treatment limb, ranging from 8.9% to 9.8% for benazepril+amlodipine and from 9.9% to 16.0% for benazepril+hydrochlorothiazide. Composite end point rates were higher in the benazepril+hydrochlorothiazide compared with the benazepril+amlodipine treatment limb in all subgroups (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Composite trial outcomes among additional secondary subgroups. Forest plot representing the adjusted hazard ratios±95% confidence intervals by Cox proportional hazard model in favor of benazepril (B)+amlodipine (A) therapy by secondary subgroups. In each antihypertensive medication subgroup, participants were taking the specific medication(s) listed without overlap between unique subgroups. Patients could not be included in >1 subgroup. For example, patients in the calcium channel blocker (CCB) alone, ACEI (angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor) alone, ACEI+CCB, and ACEI+diuretic subgroups were all different individuals. The exception is that there were overlaps in patients between subgroups containing the term “or” in the definition. For example, patients could be in both the ACEI+diuretic group and the ACEI or angiotensin receptor blocker [ARB]+diuretic subgroup. Patients using other antihypertensive agents not listed in the figure (eg, β or α blockers) were not excluded from these subgroups. Other subgroups listed include background lipid‐lowering therapy and systolic blood pressure (SBP) control status on trial randomization. CI indicates confidence interval; H, hydrochlorothiazide; HMG‐CoA, 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl coenzyme‐A reductase inhibitor (statin); and mod, modifying.

Table 2.

Composite Primary Event Rates in the Treatment Limbs for Each Subgroup

| Study Subgroup | Benazepril+Amlodipine Limb Events (%) | Benazepril+Hydrochlorothiazide Limb Events (%) |

|---|---|---|

| ACEI+CCB (n=1375) | 60 (8.88) | 112 (16.0) |

| ACEI+diuretic (n=1419) | 64 (9.40) | 79 (10.7) |

| ACEI or ARB+diuretic (n=2745) | 124 (9.25) | 151 (10.75) |

| ARB+diuretic (n=1326) | 60 (9.19) | 72 (10.79) |

| ACEI alone (n=2562) | 127 (9.67) | 136 (10.9) |

| (ACEI or ARB alone) or ([ACE or ARB]+diuretic) (n=6336) | 295 (9.37) | 340 (10.65) |

| Not ACEI or ARB+CCB or diuretic (n=6975) | 323 (9.16) | 372 (10.77) |

| CCB alone (n=717) | 35 (9.49) | 40 (11.5) |

| ACEI or ARB alone (n=3591) | 171 (9.46) | 189 (10.58) |

| ARB alone (n=1032) | 44 (8.91) | 53 (9.85) |

| Statin only or with other lipid‐lowering drug (n=7635) | 365 (9.75) | 462 (11.87) |

| Baseline systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg (n=6977) | 327 (9.44) | 426 (12.13) |

| Baseline systolic BP <140 mm Hg (n=4480) | 202 (8.96) | 227 (10.2) |

ACE indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ACEI, ACE inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BP, blood pressure; and CCB, calcium channel blocker.

The following results are for the model involving the entire cohort of patients that included an interaction term to test for effect modification on the HRs by subgroups (prior treatments). Other than for the ACEI+CCB subgroup, there was no evidence of effect modification (nonsignificant interaction terms) on the main composite end point for any other subgroup evaluated (Table 3). To explore for reasons underlying the greater benefit in the ACEI+CCB subgroup, we evaluated for differences in characteristics among these participants (Table 4). Although some clinical variables were statistically different, adding these to the model did not eliminate the significance of the interaction term (P=0.006). Controlling for achieved BP levels at 6 months into the trial also did not substantively alter these findings.

Table 3.

Significance of the Interaction Terms for Effect Modification for Each Subgroup on the HR Between Study Treatment Limbs

| Study Subgroup | P Value for Interaction Term |

|---|---|

| ACEI+CCB (n=1375) | 0.005 |

| ACEI+diuretic (n=1419) | 0.844 |

| ACEI or ARB+diuretic (n=2745) | 0.688 |

| ARB+diuretic (n=1326) | 0.739 |

| ACEI alone (n=2562) | 0.431 |

| ACEI or ARB+CCB or diuretic (n=4475) | 0.307 |

| Not ACEI or ARB+CCB or diuretic (n=6975) | 0.307 |

| CCB alone (n=717) | 0.752 |

| ACEI or ARB alone (n=3591) | 0.383 |

| ARB alone (n=1032) | 0.797 |

| Statin only or with other lipid‐lowering drug (n=7635) | 0.769 |

| Baseline systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg (n=6977) | 0.551 |

| Baseline systolic BP <140 mm Hg (n=4480) | 0.551 |

Model adjusted for baseline age, smoking status, history of myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, hospitalization for unstable angina, systolic and diastolic BP, and left ventricular hypertrophy. ACEI indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BP, blood pressure; CCB, calcium channel blocker; and HR, hazard ratio.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the Study Participants in the ACEI+CCB Subgroup Versus All Other Participants

| Subject Characteristics | ACEI+CCB | All Other Participants | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects, n (%) | 1375 (12.0) | 10 075 (88.0) | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.121 | ||

| Male | 860 (62.6) | 6082 (60.4) | |

| Female | 515 (37.5) | 3993 (39.6) | |

| Age, mean±SD, y | 68.4±7.1 | 68.4±6.8 | 0.996 |

| ≥65 y, n (%) | 897 (65.2) | 6703 (66.5) | 0.341 |

| ≥70 y, n (%) | 563 (41.0) | 4113 (40.8) | 0.931 |

| Race or ethnic group, n (%) | 0.0002 | ||

| Black | 242 (17.6) | 1130 (11.2) | <0.0001 |

| White | 1074 (78.1) | 8527 (84.6) | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic | 85 (6.2) | 537 (5.3) | 0.191 |

| Other | 54 (3.9) | 374 (3.7) | 0.693 |

| Region, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| United States | 1138 (82.8) | 6959 (69.1) | |

| Nordic countries | 237 (17.2) | 3116 (30.9) | |

| Anthropometrics, mean±SD | |||

| Weight, kg | 89.0±19.0 | 88.5±18.9 | 0.396 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 104.0±16.2 | 103.8±15.2 | 0.714 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 31.1±6.2 | 30.9±6.2 | 0.354 |

| Medications, n (%) | |||

| Lipid‐lowering agents | 939 (68.9) | 6756 (67.8) | 0.393 |

| β Blockers | 584 (42.9) | 4797 (48.1) | 0.0003 |

| Antiplatelet agents | 876 (64.3) | 6292 (63.1) | 0.396 |

| Hemodynamics, mean±SD | |||

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 144.7±17.9 | 145.5±18.3 | 0.131 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 79.0±10.6 | 80.2±10.8 | 0.0002 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 70.8±10.7 | 70.3±11.0 | 0.126 |

| Laboratory values, mean±SD | |||

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.97±0.28 | 0.99±0.27 | 0.055 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 128.4±48.0 | 127.3±46.1 | 0.431 |

| Potassium, mmol/dL | 4.3±0.4 | 4.3±0.4 | 0.535 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 183.5±38.2 | 184.5±39.8 | 0.418 |

| HDL‐C, mg/dL | 49.6±14.2 | 49.4±14.0 | 0.788 |

| Risk factors, n (%) | |||

| Myocardial infarction | 294 (21.4) | 2409 (23.9) | 0.038 |

| Stroke | 188 (13.7) | 1305 (13.0) | 0.457 |

| Hospitalization for United States | 166 (12.1) | 1157 (11.5) | 0.522 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 851 (61.9) | 6053 (60.1) | 0.198 |

| Renal disease | 118 (8.6) | 584 (5.8) | <0.0001 |

| Coronary revascularization | 512 (37.2) | 3595 (35.7) | 0.260 |

| CABG | 315 (22.9) | 2124 (21.1) | 0.121 |

| PCI | 275 (20.0) | 1898 (18.8) | 0.303 |

| Other, n (%) | |||

| LVH | 176 (13.2) | 1351 (13.7) | 0.586 |

| Current smoking | 157 (11.4) | 1138 (11.3) | 0.893 |

| Dyslipidemia | 1060 (77.1) | 7473 (74.2) | 0.02 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 90 (6.6) | 686 (6.8) | 0.715 |

ACEI indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; BP, blood pressure; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CCB, calcium channel blocker; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; and PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Discussion

The main finding of this post hoc observational analysis of the ACCOMPLISH trial is that patients who were previously receiving a combination antihypertensive regimen similar to either treatment limb used in the study (ie, RAS blocker+diuretic or CCB) derived cardiovascular benefit from allocation to benazepril+amlodipine. The risk reduction for the composite end point was similar in this primary subgroup (26%) and among all other participants (15%) and the overall trial cohort (20%).6 This suggests that cardiovascular protection can be improved not only by switching patients taking an RAS blocker+diuretic to combination therapy using benazepril+amlodipine, but also by continuing the latter regimen among individuals already receiving it. These findings are relevant to present‐day clinical practice because both regimens remain advocated as viable strategies by recent guidelines2, 3, 4 for patients requiring combination therapy to achieve BP control.6, 7, 8, 9, 10

No subgroup appeared to be harmed (all HRs, <1.0) by allocation to benazepril+amlodipine, including those previously taking any antihypertensive regimen other than those used in the primary subgroup, those taking background cholesterol‐lowering agents, and patients with systolic BP already controlled to target goal (Figure 3). It is possible that some of the HRs may not have reached traditional levels of significance principally because of reduced statistical power, given the smaller subgroup sample sizes. Nonetheless, in each scenario, the risk reductions trended in favor of benazepril+amlodipine. There was also no evidence of significant effect modification of any subgroup on the main composite outcome, except for greater benefit among those previously taking an ACEI+CCB (Tables 2 and 3). The reasons for this latter observation are not clear; however, it further supports maintaining this regimen among those already receiving it.

Clinical Implications

Taken together with previous ACCOMPLISH trial results,6 our current findings add support to the contention that high‐risk hypertensive patients will likely benefit, or at the least will not be harmed, by converting their BP‐lowering regimen to combination therapy using benazepril+amlodipine. This applies to diabetic patients, patients with coronary heart disease, and those at risk for adverse renal outcomes.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 In the present analysis, even individuals with controlled hypertension (ie, systolic BP of <140 mm Hg) or taking only a single antihypertensive agent benefitted (or trended towards benefit).

Greater BP‐lowering efficacy of benazepril+amlodipine is unlikely to explain its superiority because 24‐hour ambulatory levels did not differ between treatment limbs in a subgroup analysis (n=573) of participants in the ACCOMPLISH trial.10 We have previously reviewed several hypotheses, including therapeutic reasons (eg, reduced drug‐related adverse effects and better compliance) and biological mechanisms (eg, greater central aortic BP lowering), plausibly responsible for the greater cardiovascular risk reduction derived from initial combination therapy using benazepril+amlodipine as opposed to other regimens.5 Nevertheless, the underlying explanation(s) for these current findings and the main ACCOMPLISH trial results must remain speculative at the present time.

The evidence from several trials11, 12 and observational analyses13 supports that starting a 2‐drug regimen (ie, “initial” combination therapy) rather than a single antihypertensive agent cannot only achieve more rapid and superior BP control,4 but may also lead to better cardiovascular outcomes.14 These prior studies demonstrated the benefits of initial combination therapy in a variety of regimens. Given the superiority of benazepril+amlodipine versus benazepril+hydrochlorothiazide (even among patients taking at least 2 BP medications6), we posit that initial combination therapy specifically with RAS blockade plus CCB (when clinically appropriate and not contraindicated) may be an even more effective management strategy for the prevention of cardiovascular events than estimated by prior combination therapy studies.11, 12, 13, 14

Strengths and Limitations

We are aware of only 1 prior analysis from a major hypertension trial (VALUE [Valsartan Antihypertensive Long‐Term Use Evaluation]) in which the impact on study outcomes was evaluated in relation to prior BP‐lowering treatment regimens.15 As with the ACCOMPLISH trial, most study patients (92%) had been receiving antihypertensive therapy before entering the VALUE trial. In accordance with our findings, the study end points were not differentially affected by prior medications. This is a particularly relevant issue for contemporary clinical practice because most patients among modern trials had been already undergoing treatment with medications.1

We acknowledge that our results derive from post hoc observational analyses and, as such, must be considered hypothesis generating. Nevertheless, the consistency of responses favoring benazepril+amlodipine among all subgroups supports the overall veracity of our overarching contention. In addition, our findings only directly apply to high‐risk individuals given the characteristics of the patients in ACCOMPLISH.6 Whether the results can be extrapolated to other and lower‐risk patients is unknown; however, recent evidence supports that medical treatment is likely beneficial, even for low‐risk patients with mild hypertension.1 Positive findings in our study were observed in patients previously taking several single BP‐lowering medications and those with a systolic/diastolic BP of <140/90 mm Hg, supporting the hypothesis that even individuals with milder forms of high BP may benefit from benazepril+amlodipine. The average on‐treatment BP in the ACCOMPLISH trial was <140/90 mm Hg. Thus, any speculations of the merits of initiating combination therapy with benazepril+amlodipine implicitly presume that this regimen is capable of keeping BP controlled (alone or with additional agents as needed). This is particularly important given the recent results of the SPRINT (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial), which also supports a lower systolic BP target (120 mm Hg) than previously espoused.16 Patients were allocated to a subgroup on the basis of the medications they were taking right at study enrollment. The duration they had been treated with these agents, prior medication use in the years beforehand, and their adherence to this regimen remain unknown. However, because most subgroups derived similar relative benefits from benazepril+amlodipine, it is not likely that any unaccounted for changing of prior medications between the various regimens in the months to years before entering the trial would have differentially affected the treatment effects of the combination therapy regimens used in the ACCOMPLISH trial in a manner that explains our current findings. Finally, we were not able to explain the significantly greater benefit of benazepril+amlodipine in the ACEI+CCB subgroup (Table 3). It remains possible that unaccounted for factors (ie, not listed in Table 4) could have led to a propensity to receive ACEI+CCB combination and, thus, explains the greater benefit in this 1 subgroup.

Conclusions

High‐risk hypertensive patients achieved a greater cardiovascular risk reduction by allocation to benazepril+amlodipine compared with benazepril+hydrochlorothiazide, largely regardless of their prior medication treatment regimens, baseline BP control status, and background lipid‐lowering therapies. Our findings add further support that most hypertensive patients should strongly consider combination RAS blocker/CCB as first‐line therapy.

Sources of Funding

The original ACCOMPLISH (Avoiding Cardiovascular Events Through Combination Therapy in Patients Living with Systolic Hypertension) trial was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals.

Disclosures

Bakris reports clinical trials for Bayer; and consulting for Takeda Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, CVRx, Janssen, Eli Lilly and Company/Boehringer‐Ingelheim, Medtronic, Astra‐Zeneca, Novartis, GSK, Bayer, and Daichi‐Sankyo. Pitt reports consulting for Bayer, Merck, Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Forrest Laboratories, Relypsa, scPharmaceuticals, PharMain, Tricida, DaVinci Biosciences, Stealth Peptides, KBP BioSciences, and AuraSense; stock options in Relypsa, scPharmaceuticals, PharMain, KBP BioSciences, AuraSense, DaVinci Biosciences, Galectin Therapeutics, and Tricida; and a patent pending site‐specific delivery of eplerenone to the myocardium. Data Safety and Monitoring Boards (DSMB): Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Inc, J&J, Oxygen Biotherapeutics; and is on the events committee for Juventis. Velazquez reports consulting for Novartis, Amgen, and Merck; and has received grant support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Novartis, Amgen, Pfizer, Alynylam, and Medtronic Foundation. Zappe is an employee of Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Hau is an employee of Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Weber reports consulting for Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Company, and Forest; and speaking for Arbor Pharmaceuticals. Jamerson reports clinical trials (Bayer). The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e006940 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006940.)29301757

References

- 1. Zanchetti A, Thomopoulos C, Parati G. Randomized controlled trials of blood pressure lowering in hypertension: a critical reappraisal. Circ Res. 2015;116:1058–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison‐Himmelfarb C, Handler J, Lackland DT, LeFevre ML, MacKenzie TD, Ogedegbe O, Smith SC Jr, Svetkey LP, Taler SJ, Townsend RR, Wright JT Jr, Narva AS, Ortiz E. 2014 Evidence‐based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redón J, Zanchetti A, Böhm M, Christiaens T, Cifkova R, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Galderisi M, Grobbee DE, Jaarsma T, Kirchhof P, Kjeldsen SE, Laurent S, Manolis AJ, Nilsson PM, Ruilope LM, Schmieder RE, Sirnes PA, Sleight P, Viigimaa M, Waeber B, Zannad F; Task Force Members . 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2013;31:1281–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gradman AH, Basile JN, Carter BL, Bakris GL; American Society of Hypertension Writing Group . Combination therapy in hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2010;4:42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brook RD, Weder AB. Initial hypertension treatment: one combination fits most? J Am Soc Hypertens. 2011;5:66–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jamerson K, Weber MA, Bakris GL, Dahlöf B, Pitt B, Shi V, Hester A, Gupte J, Gatlin M, Velazquez EJ; ACCOMPLISH Trial Investigators . Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high‐risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2417–2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bakris G, Briasoulis A, Dahlof B, Jamerson K, Weber MA, Kelly RY, Hester A, Hua T, Zappe D, Pitt B; ACCOMPLISH Investigators . Comparison of benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide in high‐risk patients with hypertension and coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:255–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weber MA, Bakris GL, Jamerson K, Weir M, Kjeldsen SE, Devereux RB, Velazquez EJ, Dahlöf B, Kelly RY, Hua TA, Hester A, Pitt B; ACCOMPLISH Investigators . Cardiovascular events during differing hypertension therapies in patients with diabetes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bakris GL, Sarafidis PA, Weir MR, Dahlöf B, Pitt B, Jamerson K, Velazquez EJ, Staikos‐Byrne L, Kelly RY, Shi V, Chiang YT, Weber MA; ACCOMPLISH Trial Investigators . Renal outcomes with different fixed‐dose combination therapies in patients with hypertension at high risk for cardiovascular events (ACCOMPLISH): a prespecified secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:1173–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jamerson KA, Bakris GL, Weber MA. 24‐Hour ambulatory blood pressure in the ACCOMPLISH trial. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Feldman RD, Zou GY, Vandervoort MK, Wong CJ, Nelson SA, Feagan BG. A simplified approach to the treatment of uncomplicated hypertension: a cluster randomized, controlled trial. Hypertension. 2009;53:646–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brown MJ, McInnes GT, Papst CC, Zhang J, MacDonald TM. Aliskiren and the calcium channel blocker amlodipine combination as an initial treatment strategy for hypertension control (ACCELERATE): a randomised, parallel‐group trial. Lancet. 2011;377:312–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Egan BM, Bandyopadhyay D, Shaftman SR, Wagner CS, Zhao Y, Yu‐Isenberg KS. Initial monotherapy and combination therapy and hypertension control the first year. Hypertension. 2012;59:1124–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gradman AH, Parisé H, Lefebvre P, Falvey H, Lafeuille MH, Duh MS. Initial combination therapy reduces the risk of cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients: a matched cohort study. Hypertension. 2013;61:309–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zanchetti A, Julius S, Kjeldsen S, McInnes GT, Hua T, Weber M, Laragh JH, Plat F, Battegay E, Calvo‐Vargas C, Cieslinski A, Degaute JP, Holwerda NJ, Kobalava J, Pedersen OL, Rudyatmoko FP, Siampooulos KC, Sotset O. Outcomes in subgroups of hypertensive patients treated with regimens based upon valsartan and amlodipine: an analysis of findings from the VALUE trial. J Hypertens. 2006;24:2163–2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. SPRINT Research Group , Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, Snyder JK, Sink KM, Rocco MV, Reboussin DM, Rahman M, Oparil S, Lewis CE, Kimmel PL, Johnson KC, Goff DC Jr, Fine LJ, Cutler JA, Cushman WC, Cheung AK, Ambrosius WT. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood‐pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]