Abstract

Background

Long‐term disease progression after myocardial infarction (MI) is inadequately understood. We evaluated the pattern and angiographic properties (culprit lesion [CL]/non‐CL [NCL]) of recurrent MI (re‐MI) in a large real‐world patient population.

Methods and Results

Our observational study used prospectively collected data in 108 615 patients with first‐occurrence MI enrolled in the SWEDEHEART (Swedish Web System for Enhancement and Development of Evidence‐Based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies) between July 1, 2006 and November 29, 2014. During follow‐up (median, 3.2 years), recurrent hospitalization for MI occurred in 11 117 patients (10.2%). Of the patients who underwent coronary angiography for the index MI, a CL was identified in 44 332 patients. Of those patients, 3464 experienced an re‐MI; the infarct originated from the NCL in 1243 patients and from the CL in 655 patients. In total, 1566 re‐MIs were indeterminate events and could not be classified as NCL or CL re‐MIs. The risk of re‐MI within 8 years related to the NCL was 0.06 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.05–0.06), compared with 0.03 (95% CI, 0.02–0.03) for the CL. There were no large differences in baseline characteristics of patients with subsequent NCL versus CL re‐MIs. Independent predictors of NCL versus CL re‐ MI were multivessel disease (odds ratio, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.87–2.82), male sex (odds ratio, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.09–1.71), and a prolonged time between the index and re‐MI (odds ratio, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.10–1.22).

Conclusions

In a large cohort of patients with first‐occurrence MI undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, the risk of re‐MI originating from a previously untreated lesion was twice higher than the risk of lesions originating from a previously stented lesion.

Clinical Trial Registration

URL: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier: NCT03099395.

Keywords: culprit artery, myocardial infarction, nonculprit artery, percutaneous coronary intervention, prognosis

Subject Categories: Cardiovascular Disease, Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

The risk of recurrent myocardial infarction originating from a previously untreated lesion, or nonculprit lesion, was more than twice as high as the risk of reinfarction from a previously treated lesion among patients with myocardial infarction who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

A better understanding of long‐term disease progression and whether reinfarctions occur in previously treated (stented) lesions or in new or progressive lesions may have an impact on decisions on type and duration of medical treatment after an initial myocardial infarction.

Introduction

Globally, an estimated 17.5 million people die annually from cardiovascular disease, of which 7.5 million deaths are attributable to coronary artery disease (CAD).1

In developed countries, wider access to new pharmacological therapies and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has substantially reduced mortality after myocardial infarction (MI). Nonetheless, some patients experience subsequent ischemic events. In a large Swedish national register study of almost 100 000 patients with first‐time MI, 18.3% of patients experienced a recurrent MI (re‐MI), stroke, or cardiovascular death during the first year after the index event.2 Also, of patients who were event free during the first year after MI, 1 in 5 experienced an event during the following 3 years.2 The risk of recurrent ischemic events has been associated with clinical characteristics, such as age, diabetes mellitus, prior MI, stroke, unstable angina, heart failure, extent of CAD, and the use of revascularization for the index event,3, 4, 5 and also with biomarkers, such as high‐sensitivity troponins, C‐reactive protein, NT‐proBNP (N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide), and growth differentiation factor‐15.6, 7

Recurrent ischemic events can occur at the original treatment site or in previously untreated lesions that are new or progressive. In the prospective PROSPECT (Providing Regional Observations to Study Predictors of Events in the Coronary Tree) study, lesion‐related factors were studied with multimodality imaging in 697 patients.8 Of the 132 patients (20.4%) who experienced an ischemic event during the follow‐up, approximately half of patients had events related to the nonculprit lesions (NCLs; n=74 [11.6%]) and half had events related to the culprit lesion (CL; n=83 [12.9%]).

There are limited large population data describing details on the localization (affected vessel/s) and severity (non–ST‐segment–elevation MI or ST‐segment–elevation MI [STEMI]) of re‐MIs in relation to the index MI. A better understanding of the clinical predictors for the type of re‐MIs could have implications for treatment decisions after MI and also for the duration of secondary drug‐prevention therapy. We, therefore, sought to evaluate the occurrence of re‐MIs related to the NCL versus the CL and the potential clinical predictors of NCL re‐MIs.

In this study, we provide a large register‐based analysis of re‐MIs and their association with previously treated versus untreated new or progressive lesions.

Methods

This observational cohort study used prospectively collected data from the SWEDEHEART (Swedish Web System for Enhancement and Development of Evidence‐Based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies) registry and the Swedish National Board of Healthcare registries. This study was approved by the local Ethics Board at Uppsala University (Dnr 2015/241).

Because of data protection principles, the data, analytic methods, and study materials will not be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure.

Patients

The national SWEDEHEART registry includes patients with MI from all Swedish hospitals and was started after a merging of the Register of Information and Knowledge About Swedish Heart Intensive Care Admissions, the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry, the Swedish Heart Surgery Register, and the National Register of Secondary Prevention After Heart Intensive Care Admissions.9, 10

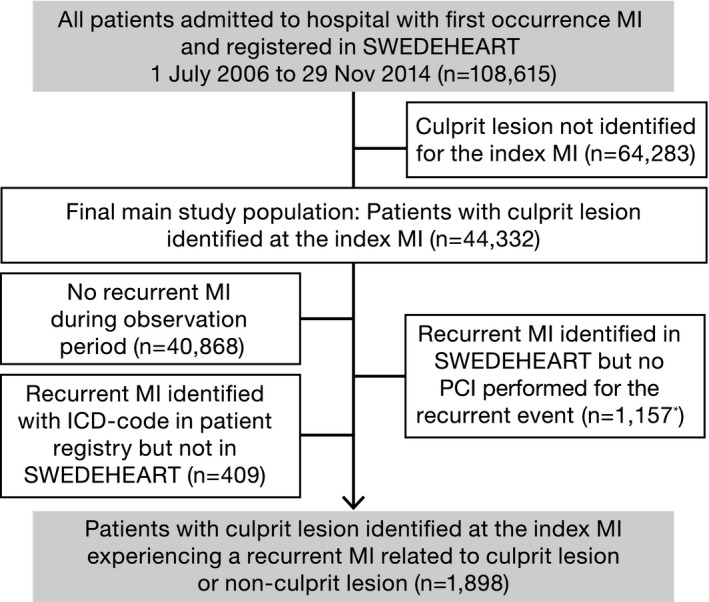

In this study, patients hospitalized for STEMI or non‐STEMI between July 1, 2006, and November 29, 2014, were included (Figure 1). Data from SWEDEHEART were merged with data from the National Patient Register for information about hospital admissions. Data linkage was performed by the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare.

Figure 1.

Patient flow chart. ICD indicates International Classification of Diseases; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; and SWEDEHEART, Swedish Web System for Enhancement and Development of Evidence‐Based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies. *Of these, 661 were invasively evaluated with coronary angiography or fractional flow reserve measurement.

Re‐MI was defined as any rehospitalization after the index MI and registered in the national patient registry or readmission in the Register of Information and Knowledge About Swedish Heart Intensive Care Admissions for MI diagnoses, according to International Classification of Diseases codes I21 and I22. Procedural data were captured in the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry, which holds data on consecutive patients from all centers that perform coronary angiography and PCI in Sweden. At coronary angiography for any indication, all previously implanted stents are displayed on the report, with information about stent type, stent characteristics, and date and time of implantation and a mandatory question about any occurrence of restenosis or stent thrombosis.

Definitions of CL‐ and NCL‐Related MIs

Patients with only 1 segment treated at their primary PCI for the index MI were defined as patients with CL identified at their index infarction and included in the NCL/CL analysis (Figure 1). For the outcome “re‐MI related to CL,” the CL needed to be defined at the index MI and treated at the re‐MI. Re‐MIs with >1 lesion treated were included in the CL definition as long as the originally treated index MI lesion was treated at recurrence. For the outcome “re‐MI related to NCL,” the CL needed to be defined at the index MI but not be among lesions treated during the first PCI for the re‐MI.

All captured events of re‐MIs not fulfilling the definitions of re‐MI related to CL or re‐MI related to NCL were defined as “indeterminate re‐MIs” and, thus, excluded from the continued NCL/CL analysis. Indeterminate re‐MIs included MIs with a conservative/noninvasive treatment approach (eg, no coronary angiography performed for the re‐MI) or if coronary angiography was performed for the re‐MI but no PCI.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables were expressed as means and SDs, and categorical variables were expressed as percentages. The time‐to‐event curves for re‐MI were calculated using Kaplan‐Meier analysis. The cumulative event proportion of NCL and CL re‐MIs was estimated from cause‐specific Kaplan‐Meier curves, not taking competing risks into account in any other way than censoring if some other type of MI or death occurred. As a sensitivity analysis, a competing risk calculation for cumulative incidences using the approach of Fine and Gray was also performed, treating the other types of MI and death as competing risks.11 For the analyses of predictors of re‐MIs related to NCL, the study population was limited to those experiencing an re‐MI, defined as either NCL or CL (Figure 1). A multivariable logistic regression was estimated with preselected predictors of clinical interest: age >75 years, male sex, smoking, previous PCI, STEMI, impaired kidney function (estimated glomerular filtration rate, <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2), multivessel disease, diabetes mellitus, reduced left ventricular function, and time to re‐MI from the index MI. All reported P values are 2‐sided. All analyses were performed with the use of R, version 3.3.2 (R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2016; https://www.R-project.org).

Results

Re‐MI After the Index Event

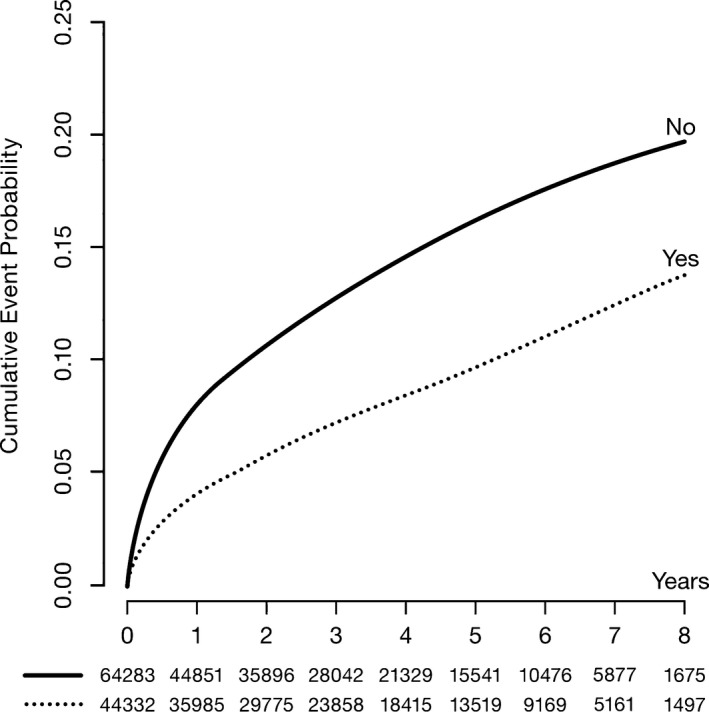

In total, 108 615 patients with first‐occurrence MI (index MI) were identified in SWEDEHEART between July 1, 2006, and November 29, 2014. During a median (interquartile range) follow‐up of 3.2 (1.3–5.6) years, recurrent hospitalization for MIs occurred in 11 117 patients (10.2%) (Figure 2). The risk of recurrent hospitalizations for MI in patients in whom the CL at the index MI could not be identified was higher than in those in whom the CL was identified (Figure S1).

Figure 2.

Cumulative event probability estimated by the Kaplan‐Meier method, and numbers of patients at risk of recurrent myocardial infarction.

Re‐MIs Related to NCLs and CLs

Of those who underwent a PCI for the index MI (n=65 976), a CL was identified in 44 332 patients. For these patients, there were a total of 3464 re‐MIs, of which 1243 were related to NCL and 655 were related to CL (Table 1). Of the 3464 re‐MIs, 1566 were indeterminate events and could not be classified as NCL or CL re‐MIs. Most of the indeterminate re‐MIs had available SWEDEHEART data (n=1157) but could not be identified as NCL/CL infarctions, because no PCI was performed for the re‐MI (most of these only performed coronary angiography or fractional flow reserve measurement). The remainder (n=409) were not treated in a SWEDEHEART unit or invasively evaluated (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Number of Events at 1 and 8 Years and Cumulative Proportion (Estimated by Kaplan‐Meier Censoring for Other Types of MI or End of Follow‐Up) of NCL‐ and CL‐Related Re‐MIs Among Patients With Identified CL (n=44 332) at the Index MI (n=108 615)

| Variable | 1 y | 8 y | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Cumulative Proportion | 95% CI | N | Cumulative Proportion | 95% CI | |

| Re‐MI related to NCL | 504 | 0.012 | 0.011 to 0.013 | 1241a | 0.055 | 0.051 to 0.059 |

| Re‐MI related to CL | 350 | 0.009 | 0.008 to 0.010 | 655 | 0.028 | 0.024 to 0.031 |

CI indicates confidence interval; CL, culprit lesion; MI, myocardial infarction; NCL, non‐CL; and Re‐MI, recurrent MI.

The number of NCL and CL re‐MIs during the full follow‐up of 8.5 years was 1243 and 655, respectively.

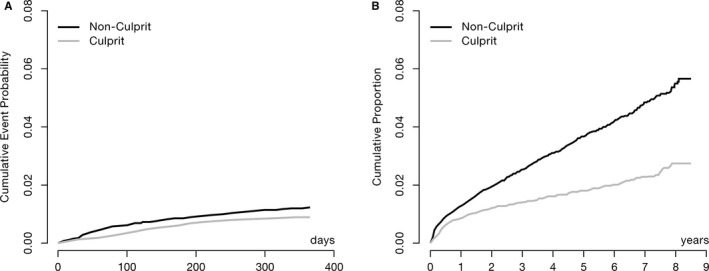

Cumulative Proportion at 1 and 8 Years for First Re‐MI Related to NCLs and CLs

There was a higher risk for re‐MIs related to NCL (cumulative proportion, 0.012; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.011–0.013) than CL (cumulative proportion, 0.009; 95% CI, 0.008–0.010) at 1 year (Table 1, Figure 3A). After 8 years’ follow‐up, the risk of NCL compared with CL re‐MIs still remained higher: cumulative proportion, 0.06 (95% CI, 0.05–0.09) and 0.03 (95% CI, 0.02–0.03) for NCL and CL, respectively (Table 1, Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Cumulative proportion calculated with 2 separate cause‐specific hazard functions, censoring if other type of myocardial infarction or end of follow‐up, for first recurrent myocardial infarction within 1 (A) and 8 (B) years related to the nonculprit (n=504 and n=1241 for 1 and 8 years, respectively) and culprit (n=350 and n=655 for 1 and 8 years, respectively) lesions.

A competing risk analysis using the approach of Fine and Gray,11 with the other types of MI and death as competing risks, yielded similar results but a slightly lower cumulative incidence: 0.05 (95% CI, 0.04–0.05) and 0.02 (95% CI, 0.02–0.03) for NCL and CL hospitalizations for re‐MIs, respectively (data not shown).

Patient Characteristics at the Index MI for Patients With Recurrent NCL‐ and CL‐Related MI

There were small differences in patient characteristics at the index MI for patients subsequently experiencing an NCL versus a CL re‐MI. Patients with NCL re‐MI were more likely to be men (75% versus 68% for NCL versus CL re‐MI) and to have extensive CAD at the index MI than those with CL re‐MI (3‐vessel disease, 18% versus 13% for NCL versus CL re‐MI) (Table 2). Furthermore, patients experiencing an NCL re‐MI were more likely to have received a new‐generation drug‐eluting stent during the procedure at the index MI (new‐generation drug‐eluting stent, 69% versus 59% for NCL versus CL re‐MI among those who received a drug‐eluting stent), but there were no large differences between groups in the overall drug‐eluting stent or bare‐metal stent use.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics at the Index Infarction for All Patients With First‐Occurrence MI With the CL Identified and the Subset of Patients With Reinfarctions Related to an NCL and CL

| Variable | First‐Occurrence MI With Artery Identified (n=44 332) | Re‐MI Related to NCL (n=1243) | Re‐MI Related to CL (n=655) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 31 155 (70.3) | 936 (75.3) | 443 (67.6) |

| Age, y | 66±11.7 | 65.1±11.4 | 65.8±11.6 |

| Body weight, kg | 81.3±15.7 | 82.8±15.7 | 80.6±15.7 |

| Indication for the coronary angiography during hospitalization for the index MI | |||

| ST‐segment–elevation MI | 23 446 (53) | 618 (49.8) | 329 (50.5) |

| Non–ST‐segment–elevation MI/unstable angina | 20 752 (47) | 624 (50.2) | 323 (49.5) |

| Coexisting conditions | |||

| Hypertension | 18 494 (42.1) | 596 (48.3) | 300 (46.2) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6314 (14.3) | 233 (18.8) | 127 (19.5) |

| Statin use at hospital admission | 7216 (16.4) | 296 (23.9) | 141 (21.6) |

| Smoker status | |||

| Current | 12 706 (29.2) | 379 (30.8) | 205 (31.4) |

| Former, >1 mo | 18 899 (32.3) | 399 (32.4) | 222 (34.0) |

| Previous MI | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Previous PCI | 1678 (2.6) | 75 (6.1) | 42 (6.4) |

| Previous stroke | 5891 (9.5) | 70 (5.8) | 40 (6.3) |

| Angiographic findings during hospitalization for the index MI | |||

| 1‐Vessel disease (not LM) | 26 912 (60.8) | 494 (39.7) | 373 (57.1) |

| 2‐Vessel disease (not LM) | 10 592 (23.9) | 479 (38.5) | 164 (25.1) |

| 3‐Vessel disease (not LM) | 5145 (11.6) | 220 (17.7) | 83 (12.7) |

| LM | 1227 (2.8) | 39 (3.1) | 27 (4.1) |

| PCI during hospitalization for the index MI | |||

| No. of stents per procedure | 1.1±0.6 | 1.1±0.5 | 1.1±0.6 |

| Drug‐eluting stent | 17 947 (43.9) | 365 (31.6) | 182 (30.0) |

| Bare‐metal stent | 23 115 (56.7) | 798 (69.3) | 429 (71.3) |

| Stent diameter, mm | 3.1±0.5 | 3.1±0.5 | 3.0±0.5 |

| Total stent length, mm | 21.5±10.8 | 21.5±10.6 | 21.6±11.2 |

| Treated vessel | |||

| RCA | 14 696 (33.1) | 441 (35.5) | 216 (33.0) |

| LM | 493 (1.1) | 10 (0.8) | 7 (1.1) |

| LAD | 19 856 (44.8) | 457 (38.6) | 302 (46.1) |

| LCX | 9996 (22.5) | 318 (25.6) | 118 (18.0) |

| Lesion severity | |||

| A | 4008 (9.0) | 116 (9.3) | 65 (9.9) |

| B1 | 16 313 (36.8) | 446 (35.9) | 204 (31.1) |

| B2 | 16 375 (36.9) | 468 (37.7) | 255 (38.9) |

| C | 7495 (16.9) | 208 (16.7) | 129 (19.7) |

| Bifurcation lesion (yes) | 3227 (7.3) | 76 (6.1) | 53 (8.1%) |

| Medications at hospital admission for the index MI | |||

| ASA | 7996 (18.2) | 322 (26.0) | 180 (27.6) |

| Clopidogrel | 862 (2.0) | 30 (2.4) | 25 (3.8) |

| Ticagrelor | 63 (0.1) | 4 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) |

| Prasugrel | 4 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Medications during PCI for the index MI | |||

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa | 10 328 (23.3) | 382 (30.7) | 205 (31.3) |

| Heparin | 30 461 (68.7) | 822 (66.2) | 453 (69.2) |

| LMWH | 1765 (4.0) | 59 (4.8) | 35 (5.3) |

| Bivalirudin | 15 935 (36.0) | 377 (30.4) | 176 (26.9) |

| Medications at hospital discharge for the index MI | |||

| ASA | 42 264 (95.8) | 1195 (96.5) | 628 (96.0) |

| Clopidogrel | 30 803 (69.6) | 1054 (84.9) | 563 (86.0) |

| Ticagrelor | 10 412 (23.5) | 128 (10.3) | 64 (9.8) |

| Prasugrel | 1076 (2.4) | 23 (1.9) | 11 (1.7) |

| β Blockers | 40 046 (90.5) | 1170 (94.2) | 598 (91.3) |

| ACE/AT II inhibitors | 34 901 (78.9) | 968 (77.9) | 533 (81.4) |

| Calcium antagonists | 4910 (11.1) | 189 (15.2) | 92 (14.0) |

| Statins | 41 787 (94.5) | 1183 (95.2) | 622 (95.0) |

| Warfarin | 2176 (4.9) | 64 (5.2) | 31 (4.7) |

Values are number (percentage) or mean±SD. Percentages are computed by group. ACE indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; AT, angiotensin; CL, culprit lesion; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCX, left circumflex artery; LM, left main stem; LMWH, low‐molecular‐weight heparin; MI, myocardial infarction; NCL, non‐CL; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA, right coronary artery; and Re‐MI, recurrent MI.

The patient characteristics at the index MI of the patients eventually experiencing an re‐MI not classified into NCL/CL (indeterminate MI) are shown in Table S1.

Patient Characteristics at the Re‐MI for Patients With Recurrent NCL‐ and CL‐Related MI

NCL re‐MIs were less likely to be STEMIs than CL re‐MIs (STEMI, 25% versus 39% for NCL versus CL re‐MI) (Table 3). Stent thrombosis accounted for 22 (3.7%) of the re‐MIs occurring at a CL. At the re‐MI, the complexity of CAD was similar between groups (3‐vessel disease and left main disease, 14% and 4% versus 15% and 4% for NCL and CL re‐MIs, respectively). The angiographic findings at the re‐MI for the patients with indeterminate re‐MIs undergoing angiography are shown in Table S2.

Table 3.

Patient and Procedural Characteristics at the Re‐MI for Patients With Identified CL at the Index Infarction and NCL or CL Re‐MI

| Variable | Re‐MI Related to NCL (n=1243) | Re‐MI Related to CL (n=655) |

|---|---|---|

| Indication for the procedure during the hospitalization | ||

| ST‐segment–elevation MI | 312 (25.2) | 255 (38.9) |

| Non–ST‐segment–elevation MI | 688 (55.5) | 338 (51.6) |

| Angiographic findings at the re‐MI | ||

| 1‐Vessel disease (not LM) | 626 (50.8) | 346 (53.3) |

| 2‐Vessel disease (not LM) | 377 (30.6) | 178 (27.4) |

| 3‐Vessel disease (not LM) | 174 (14.1) | 96 (14.8) |

| Main stem | 53 (4.3) | 25 (3.9) |

| Definitive stent thrombosis | 23 (1.9) | 24 (3.7) |

| PCI for the re‐MI | ||

| No. of stents per procedure | 1.4±1.0 | 1.2±1.1 |

| Drug‐eluting stent | 744 (66.8) | 370 (78.4) |

| Bare‐metal stent | 391 (35.2) | 111 (23.6) |

| Stent diameter, mm | 3.0±0.5 | 3.1±0.6 |

| Total stent length, mm | 28.6±19.9 | 31.6±21.0 |

| Treated vessel | ||

| RCA | 425 (34.2) | 229 (35.0) |

| LM | 38 (3.1) | 15 (2.3) |

| LAD | 514 (41.4) | 325 (49.6) |

| LCX | 385 (31.0) | 152 (23.2) |

| Lesion severity | ||

| A | 92 (7.4) | 29 (4.4) |

| B1 | 413 (33.2) | 179 (27.3) |

| B2 | 502 (40.4) | 258 (27.3) |

| C | 231 (18.6) | 181 (27.6) |

| Bifurcation lesion | 137 (11.0) | 52 (7.9) |

| Medication before and under PCI | ||

| ASA (admission) | 1186 (95.5) | 625 (95.7) |

| Clopidogrel (admission) | 757 (61.0) | 411 (62.8) |

| Ticagrelor (admission) | 353 (47.8) | 148 (48.5) |

| Prasugrel (admission) | 32 (3.3) | 21 (4.7) |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (during PCI) | 130 (10.5) | 119 (18.2) |

| Heparin (during PCI) | 976 (78.5) | 482 (73.6) |

| LMWH (before/during PCI) | 43 (3.5) | 23 (3.5) |

| Bivalirudin (during PCI) | 351 (28.2) | 204 (31.1) |

Values are number (percentage) or mean±SD. ASA indicates acetylsalicylic acid; CL, culprit lesion; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCX, left circumflex artery; LM, left main stem; LMWH, low‐molecular‐weight heparin; MI, myocardial infarction; NCL, non‐CL; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA, right coronary artery; and Re‐MI, recurrent MI.

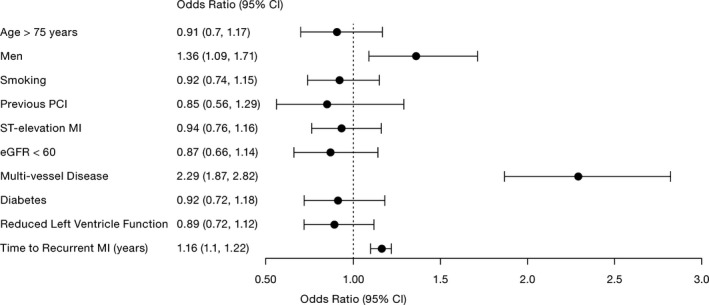

Clinical Correlates With NCL Re‐MI

Multivessel disease (odds ratio, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.87–2.82), time to re‐MI (odds ratio, 1.16 years; 95% CI, 1.10–1.22 years), and male sex (odds ratio, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.09–1.71) were identified as factors associated with a higher risk of an NCL re‐MI compared with CL re‐MIs (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Multivariable logistic regression model of risk factors for experiencing a nonculprit lesion vs culprit lesion recurrent myocardial infarction during follow‐up in the subset of patients with the culprit lesion identified at index (n=44 332). CI indicates confidence interval; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; MI, myocardial infarction; and PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Discussion

In this large cohort of 44 332 patients with first‐occurrence MI with the CL identified during PCI, the risk of re‐MIs not originating from a previously stented lesion was twice as high as the risk of lesions originating from a previously stented lesion. Consequently, although the patients with an MI underwent a PCI for the coronary stenosis believed to need revascularization, most patients, in fact, experienced re‐MIs that did not originate from the treated lesion.

In the PROSPECT study, which prospectively enrolled 697 patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing coronary angiography and radiofrequency intravascular ultrasonographic imaging after PCI, the cumulative major cardiovascular event rate was 20.4% during the follow‐up of 3.4 years. Major events were almost equally divided between previously untreated and treated lesions.8 The lower proportion of CL‐related events (CL versus NCL, n=655 versus n=1243) in the current study compared with that observed in the PROSPECT study (CL versus NCL, n=83 versus n=74) could relate to several differences between the 2 studies. In the PROSPECT study, a composite of cardiac events (death from cardiac causes, cardiac arrest, MI, rehospitalization for unstable or progressive angina, revascularization, and stent thrombosis) was assessed for its relation to the CL, where MIs (n=21) constituted only a smaller proportion of the total events (n=132). The current study subclassified a total of 1898 MIs into NCL and CL reinfarctions. Improved stents, improved stenting techniques,12 and redefined antithrombotic treatment13, 14, 15 for the short‐term phase have had a substantial impact on stent‐related adverse outcomes, but perhaps this impact is less on overall disease progression and the risk of NCL‐related adverse outcomes.16 Mortality from coronary heart disease has decreased substantially in recent decades. Reductions are attributed approximately half to major risk factor reduction (eg, reduction in cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, and smoking) and half to treatments (eg, initial treatment and revascularization after MI and treatments for heart failure).17 Unfortunately, the reductions have been counterbalanced by increases in diabetes mellitus prevalence and body mass index.18 This highlights the importance of long‐term secondary preventive treatment to reduce the overall progression of coronary heart disease.

At the index infarction, no major differences were identified between patients with subsequent NCL compared with CL recurrent infarctions on baseline characteristics. When analyzing clinical factors available for the treating clinician at the index MI, multivessel disease and male sex were associated with a higher likelihood of experiencing an NCL‐related re‐MI. Also, a longer time delay between the index infarction and the re‐MI increased the likelihood of the recurrent infarction being classified as an NCL. The risk of experiencing an NCL versus CL reinfarction at 1 year showed a similar relationship to that after the full 8‐year follow‐up (data not shown). This suggests that the higher risk of NCL reinfarctions was not affected by the unequal higher initial risk, which is coherent with STEMI,19 the higher risk of procedural MIs early after an index MI, or dual‐antiplatelet treatment usually limited to the first year after MI.20

In the PROSPECT study, patients with high‐risk lesions exhibited an overall higher morbidity (by Framingham risk score), more extensive CAD, and a higher likelihood of NCL reinfarctions.21 Clinical and angiographic characteristics had a poor predictive value for identifying recurrent ischemic events from untreated plaques. The potential of identifying coronary plaque vulnerability with intravascular ultrasonographic imaging laid the groundwork for the ongoing PROSPECT II study (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03099395?term=NCT03099395&rank=1), with the aim to establish the utility of intravascular ultrasonographic imaging and near‐infrared spectroscopy to identify plaques prone to future ischemic events. When we evaluated clinical factors possibly associated with type of recurrent infarction, index MI multivessel disease was the strongest predictor of NCL re‐MIs. Although coronary plaque phenotype has been strongly associated with NCL recurrent ischemic events8, 22, 23 and, therefore, suggests a potential clinical benefit of a more extensive and comprehensive characterization of plaques, these techniques are not extensively available in most countries. Information on the extent of CAD or the presence of multivessel disease is readily available from the index MI catheterization and, thus, likely useful for the prediction of reinfarctions not related to the CL.

A better understanding of long‐term disease progression and whether reinfarctions occur in previously treated lesions or in new or progressive lesions may have an impact on decisions on type and duration of medical treatment after an initial MI. Secondary prevention after MI is indicated to prevent the patient from stent‐related adverse events in the short to medium term and also to prevent atherothrombotic events from nontreated lesions long term and overall coronary disease progression.

Limitations

Limitations include the observational study design with potential inherent residual confounding. Nonetheless, data used for this report are based on a substantial and large number of variables, with few data missing. The large sample size allows statistical power for multiple candidate variables in the adjusted analyses. The SWEDEHEART quality registry and the national registries of the Swedish Health and Welfare are administrative data sets not primarily established for research purposes and carry some important limitations. The large sample size can potentially be offset by poor quality of the data. Nonetheless, the prospectively enrolled patients admitted to cardiac units in Sweden with symptoms suggestive of an MI and data accuracy are audited by an external monitor annually against source documents (agreement, 96%).9 The nature of our cohort study and the fact that an invasive strategy was not dictated led to a high proportion of indeterminate MIs. Also, because no angiograms were core laboratory assessed, the definition of NCL and CL was based on information provided on segment level in the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry. For the index MI, only MIs in which the CL was treated were considered for further analyses because the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry lacks information on operator‐assessed CL.

Conclusions

In this large observational study of patients after MI, the risk of re‐MIs not originating from a previously stented lesion was twice as high as the risk of lesions originating from a previously stented lesion. Multivessel disease, male sex, and time since the index MI were the strongest predictors of future NCL re‐MIs.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by AstraZeneca.

Disclosures

Varenhorst reports institutional research grants from AstraZeneca and The Medicines Company; lecture and advisory board fees from AstraZeneca, The Medicines Company, and Boeringer Ingelheim; and lecture fees from Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer, and CSL Behring. Varenhorst is on the Clinical Endpoint Committee for Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Philips, and AstraZeneca. Hasvold reports full‐time employment at AstraZeneca. Johansson reports full‐time employment at AstraZeneca. Janzon reports lecture fees from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Cambio; and advisory board fees from AstraZeneca. Albertsson reports institutional research grants from AstraZeneca. Leosdottir reports lecture and consultancy fees from Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, MSD, and Sanofi; and research grants from Astra Zeneca. Hambraeus reports lecture fees from Amgen and AstraZeneca. James reports institutional research grants from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Abbot, Boston Scientific, and The Medicines Company; and honoraria from Boston Scientific and Bayer. Jernberg reports lecture and consulting fees from Astra Zeneca, MSD, and Aspen. Svennblad reports institutional research grants from AstraZeneca and The Medicines Company. Lagerqvist reports institutional research grants from AstraZeneca.

Supporting information

Table S1. Baseline Characteristics at the Index Infarction of Patients With First‐Occurrence Myocardial Infarction With Culprit Lesion Identified and Indeterminate Recurrent Myocardial Infarction During Follow‐Up

Table S2. Angiographic Findings in the Subgroup of Patients With Identified Culprit Lesion at the Index Infarction and Indeterminate Recurrent Myocardial Infarction Undergoing Coronary Catheterization

Figure S1. Cumulative event probability estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and numbers of patients at risk of recurrent myocardial infarction in patients with (yes) and without (no) the culprit lesion identified for the index myocardial infarction.

Acknowledgments

We thank the hospitals participating in the Swedish Web System for Enhancement and Development of Evidence‐Based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies registry and acknowledge Inger Ekman (UCR (Uppsala Clinical Research Center)) and Helena Goike (AstraZeneca Nordic‐Baltic) for administrative assistance.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e007174 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007174.)

References

- 1. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jernberg T, Hasvold P, Henriksson M, Hjelm H, Thuresson M, Janzon M. Cardiovascular risk in post‐myocardial infarction patients: nationwide real world data demonstrate the importance of a long‐term perspective. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1163–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Scirica BM. Acute coronary syndrome: emerging tools for diagnosis and risk assessment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1403–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Granger CB, Goldberg RJ, Dabbous O, Pieper KS, Eagle KA, Cannon CP, Van De Werf F, Avezum A, Goodman SG, Flather MD, Fox KA; Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events I nvestigators. Predictors of hospital mortality in the global registry of acute coronary events. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2345–2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eagle KA, Lim MJ, Dabbous OH, Pieper KS, Goldberg RJ, Van de Werf F, Goodman SG, Granger CB, Steg PG, Gore JM, Budaj A, Avezum A, Flather MD, Fox KA; GRACE Investigators . A validated prediction model for all forms of acute coronary syndrome: estimating the risk of 6‐month postdischarge death in an international registry. JAMA. 2004;291:2727–2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lindholm D, James SK, Bertilsson M, Becker RC, Cannon CP, Giannitsis E, Harrington RA, Himmelmann A, Kontny F, Siegbahn A, Steg PG, Storey RF, Velders MA, Weaver WD, Wallentin L; PLATO Investigators . Biomarkers and coronary lesions predict outcomes after revascularization in non‐ST‐elevation acute coronary syndrome. Clin Chem. 2016;63:573–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Klingenberg R, Aghlmandi S, Raber L, Gencer B, Nanchen D, Heg D, Carballo S, Rodondi N, Mach F, Windecker S, Juni P, vonEckardstein A , Matter CM, Luscher TF. Improved risk stratification of patients with acute coronary syndromes using a combination of hsTnT, NT‐proBNP and hsCRP with the GRACE score. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2016. Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/2048872616684678?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed. Accessed December 18, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stone GW, Maehara A, Lansky AJ, de Bruyne B, Cristea E, Mintz GS, Mehran R, McPherson J, Farhat N, Marso SP, Parise H, Templin B, White R, Zhang Z, Serruys PW; PROSPECT Investigators . A prospective natural‐history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:226–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jernberg T, Attebring MF, Hambraeus K, Ivert T, James S, Jeppsson A, Lagerqvist B, Lindahl B, Stenestrand U, Wallentin L. The Swedish Web‐system for enhancement and development of evidence‐based care in heart disease evaluated according to recommended therapies (SWEDEHEART). Heart. 2010;96:1617–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harnek J, Nilsson J, Friberg O, James S, Lagerqvist B, Hambraeus K, Cider A, Svennberg L, Attebring MF, Held C, Johansson P, Jernberg T. The 2011 outcome from the Swedish Health Care Registry on Heart Disease (SWEDEHEART). Scand Cardiovasc J. 2013;47(suppl 62):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sarno G, Lagerqvist B, Nilsson J, Frobert O, Hambraeus K, Varenhorst C, Jensen UJ, Todt T, Gotberg M, James SK. Stent thrombosis in new‐generation drug‐eluting stents in patients with STEMI undergoing primary PCI: a report from SCAAR. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Westman PC, Lipinski MJ, Torguson R, Waksman R. A comparison of cangrelor, prasugrel, ticagrelor, and clopidogrel in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a network meta‐analysis. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2017;18:79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. O'Donoghue M, Antman EM, Braunwald E, Murphy SA, Steg PG, Finkelstein A, Penny WF, Fridrich V, McCabe CH, Sabatine MS, Wiviott SD. The efficacy and safety of prasugrel with and without a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous intervention: a TRITON‐TIMI 38 (Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition With Prasugrel‐Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction 38) analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:678–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shimada YJ, Bansilal S, Wiviott SD, Becker RC, Harrington RA, Himmelmann A, Neely B, Husted S, James SK, Katus HA, Lopes RD, Steg PG, Storey RF, Wallentin L, Cannon CP; PLATO Investigators . Impact of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors on the efficacy and safety of ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes: analysis from the Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) Trial. Am Heart J. 2016;177:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fokkema ML, James SK, Albertsson P, Aasa M, Akerblom A, Calais F, Eriksson P, Jensen J, Schersten F, de Smet BJ, Sjogren I, Tornvall P, Lagerqvist B. Outcome after percutaneous coronary intervention for different indications: long‐term results from the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR). EuroIntervention. 2016;12:303–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, Critchley JA, Labarthe DR, Kottke TE, Giles WH, Capewell S. Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2388–2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Writing Group M embers, Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Despres JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Isasi CR, Jimenez MC, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, McGuire DK, Mohler ER III, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Rosamond W, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics—2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38–e360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McManus DD, Gore J, Yarzebski J, Spencer F, Lessard D, Goldberg RJ. Recent trends in the incidence, treatment, and outcomes of patients with STEMI and NSTEMI. Am J Med. 2011;124:40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Varenhorst C, Jensevik K, Jernberg T, Sundstrom A, Hasvold P, Held C, Lagerqvist B, James S. Duration of dual antiplatelet treatment with clopidogrel and aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:969–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bourantas CV, Garcia‐Garcia HM, Farooq V, Maehara A, Xu K, Genereux P, Diletti R, Muramatsu T, Fahy M, Weisz G, Stone GW, Serruys PW. Clinical and angiographic characteristics of patients likely to have vulnerable plaques: analysis from the PROSPECT study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:1263–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stone PH, Saito S, Takahashi S, Makita Y, Nakamura S, Kawasaki T, Takahashi A, Katsuki T, Nakamura S, Namiki A, Hirohata A, Matsumura T, Yamazaki S, Yokoi H, Tanaka S, Otsuji S, Yoshimachi F, Honye J, Harwood D, Reitman M, Coskun AU, Papafaklis MI, Feldman CL; PREDICTION Investigators . Prediction of progression of coronary artery disease and clinical outcomes using vascular profiling of endothelial shear stress and arterial plaque characteristics: the PREDICTION Study. Circulation. 2012;126:172–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Calvert PA, Obaid DR, O'Sullivan M, Shapiro LM, McNab D, Densem CG, Schofield PM, Braganza D, Clarke SC, Ray KK, West NE, Bennett MR. Association between IVUS findings and adverse outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease: the VIVA (VH‐IVUS in Vulnerable Atherosclerosis) Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:894–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Baseline Characteristics at the Index Infarction of Patients With First‐Occurrence Myocardial Infarction With Culprit Lesion Identified and Indeterminate Recurrent Myocardial Infarction During Follow‐Up

Table S2. Angiographic Findings in the Subgroup of Patients With Identified Culprit Lesion at the Index Infarction and Indeterminate Recurrent Myocardial Infarction Undergoing Coronary Catheterization

Figure S1. Cumulative event probability estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and numbers of patients at risk of recurrent myocardial infarction in patients with (yes) and without (no) the culprit lesion identified for the index myocardial infarction.