Abstract

Background

Among young adults, cigarette smoking is strongly associated with alcohol and marijuana use. The present study compared self-reported co-use of cigarettes and alcohol versus cigarettes and marijuana among young adults using cross-sectional survey data.

Methods

Participants were young adult cigarette smokers (age 18 to 25) who also reported past month alcohol or marijuana use enrolled in a randomized trial testing a smoking cessation intervention on Facebook. Participants self-reported extent of cigarette smoking under the influence of alcohol or marijuana and differences in perceived pleasure from cigarette smoking when drinking alcohol compared to using marijuana.

Results

Among cigarette smokers who drank alcohol and used marijuana in the past month (n=200), a similar percentage of cigarettes were smoked under the influence of alcohol (42.4%±31.2%) and marijuana (43.1% ±30.0%). Among alcohol + marijuana users, perceived pleasure from smoking cigarettes was significantly greater when drinking alcohol versus when using marijuana (t(199)=7.05, p<0.001). There was, on average, an increase in perceived pleasure from smoking cigarettes when drinking alcohol, though perceived pleasure did not differ by binge drinking frequency. In contrast, there was on average no change in perceived pleasure from smoking cigarettes when using marijuana. Results from the cigarette smokers who used alcohol + marijuana were similar to cigarette smokers who only used alcohol (n=158) or only used marijuana (n=54).

Conclusion

Findings highlight greater perceived reward from smoking cigarettes when drinking alcohol compared to when using marijuana, informing smoking cessation interventions that target users of multiple substances.

Keywords: Ethanol, Cannabis, smoke, Tobacco, reward, Co-use

Introduction

Cigarette smoking is strongly associated with alcohol use (SAMHSA 2014, 6.30B), and smoking is especially common among heavy drinkers and binge drinkers (Bobo & Husten 2000; Falk et al. 2006; Harrison & McKee 2011; SAMHSA 2014, 6.30B; Weitzman & Chen 2005). Cigarettes and alcohol can have combined pharmacological effects that can result in a heightened reward (Glautier et al. 1996; Perkins et al. 1995; Rose et al. 2004), and may contribute to their co-use. Previous research found that young adults reported increased pleasure from smoking cigarettes under the influence of alcohol (McKee et al. 2004; Nichter et al. 2006; Stromberg et al. 2007), which could be an important factor underlying their co-use.

The relationship between frequency of binge drinking and pleasure from smoking remains unclear. We previously reported differences in tobacco use characteristics among young adults who all drank alcohol but differed in binge drinking frequency (Gubner et al. 2016). Compared to alcohol use with no binge drinking, frequent binge drinking was associated with smoking more cigarettes per day, and greater temptations to smoke in positive affective/social situations. Other smoking characteristics, such as being a social smoker, were associated with any past month binge drinking. We also reported a high rate of cigarette smoking on days participants binge drank alcohol (similar to McKee et al., 2004), suggesting that cigarettes could have greater rewarding effects when larger amounts of alcohol are consumed. For the current study, we examined the hypothesis that greater pleasure from smoking cigarettes would be found among individuals who binge drink alcohol more frequently, e.g. engage in cigarette smoking when larger amounts of alcohol are consumed.

Cigarette smoking and marijuana use are also strongly associated (Agrawal et al. 2012; Peters et al. 2012; Ramo et al. 2012; Ramo & Prochaska 2012a). Similar to alcohol, marijuana use and dependence are more common among cigarette smokers compared to nonsmokers (SAMHSA 2014, 6.9B), and marijuana use is associated with greater nicotine dependence and heavier patterns of cigarette smoking among young adults (Agrawal & Lynskey 2009; Patton et al. 2006; SAMHSA 2014, 6.9B). The literature on combined effects of tobacco and marijuana suggest that shared genetic risk factors and neurobiological pathways may explain some overlap in addictive processes for the two substances (Agrawal et al. 2010; Balfour & Ridley 2000; Huizink et al. 2010; Lingford-Hughes & Nutt 2003; Nestler 2005; Oleson & Cheer 2012; Young et al. 2006). There is evidence that cannabinoid receptors may be involved in the rewarding effects of nicotine and that cannabinoid receptor agonists may increase the rewarding and reinforcing effects of nicotine (Gamaleddin, et al., 2012; Ignatowska-Jankowska, et al., 2013; Navarrete et al., 2013; Panlilio et al., 2013). Subthreshold doses of Delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and nicotine in combination (but not alone) were found to induce a conditioned place preference in mice (Valjent et al., 2002), suggesting possible synergistic enhancement on reward processes. Differences between cigarette smokers and non-smokers in response to endocannabinoid modulation of reward processing in the nucleus accumbens have also been reported (Jansma et a., 2013). Behavioral studies have pointed to additional reasons for co-using tobacco and marijuana, including to enhance the high from marijuana or to counteract certain effects of marijuana (Schauer et al., 2016). However, to date, limited research has examined rewarding effects of marijuana and tobacco co-use.

Using cross-sectional survey data, we examined extent of cigarette smoking under the influence of alcohol or marijuana and differences in perceived pleasure from cigarette smoking when drinking alcohol compared to using marijuana among cigarette smokers who used marijuana and alcohol. Hypotheses were: (1) a similar proportion of smoking episodes would occur under the influence of alcohol and marijuana; (2) perceived pleasure would increase from smoking when drinking alcohol and using marijuana, and not differ across substance; and (3) perceived pleasure from alcohol would be greater with more frequent binge drinking. Perceived pleasure from smoking when drinking alcohol or when using marijuana was also compared between the cigarette smokers who used both marijuana and alcohol in the past month and cigarette smokers who only drank alcohol or only used marijuana.

Perceived pleasure experienced from smoking cigarettes when drinking alcohol or using marijuana could underlie the persistence of use over time and problems with cutting down or quitting (Amos et al. 2004; Cook et al. 2012; Leeman et al. 2008). Given the high prevalence of co-use of cigarettes with either alcohol or marijuana (SAMHSA 2014, 6.30B, 6.9B) and previous research suggesting that co-use is associated with greater nicotine dependence potentially undermining smoking cessation (Agrawal & Lynskey 2009; Dani & Harris, 2005), results of this study could inform the design of specific intervention components addressing substance co-use in smoking cessation interventions for young adults.

Methods

Participants and recruitment procedure

The study analyzed baseline survey data from a randomized controlled trial of English literate young adults, age 18–25, residing in the United States, who reported smoking at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and currently smoked at least 3 days per week. A full description of the study design and protocol is described in Ramo et al., 2015. Because the study was designed to examine the efficacy of a Facebook smoking cessation intervention, participants also had to use Facebook at least 4 days per week. Recruitment occurred between October 2014 and August 2015 through a paid advertising campaign on Facebook. Participants were screened for eligibility online, and, if eligible, signed an online University of California Institutional Review Board-approved informed consent, and sent proof of identity. Verified participants were sent the baseline survey online, assessing demographics, smoking, and other health risk behaviors, including alcohol and marijuana use.

Of the 7540 respondents who passed online eligibility screening, 1039 signed online consent; 739 (90.3%) sent verification of identity online; and 500 (67.8%) completed a baseline assessment. Enrollment rates were consistent with those reported in online smoking studies (Cobb et al. 2005; McKay et al. 2008; Swartz et al. 2006).

The primary analyses for the present study used baseline data from a subsample of participants (N=200) who reported past 30-day use of both alcohol and marijuana in addition to tobacco. Results were also compared to cigarette smokers who only used marijuana (n=54) or only drank alcohol (n=158) in the past month.

Measures

Demographic and substance use measures used here have previously demonstrated good reliability and validity with young adults (Ramo et al. 2011; 2012b).

Sociodemographics assessed were gender, age, ethnicity, years of education, and annual household income.

Participants were asked “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your life” (yes/no), followed by “What is the usual number of cigarettes you smoke in a day,” and “On average, how many days in a week do you smoke cigarettes” (Hall et al. 2006).

Participants were asked if they had consumed alcohol in the past 30 days, if “yes,” they were also asked to report how often they drank alcohol, how many standard drinks they consumed on a typical day, and on how many of the past 30 days they binge drank alcohol. Binge drinking was defined as having 4 or more alcoholic drinks for women, 5 or more alcoholic drinks for men (NIAAA, 2004).

Marijuana use was assessed as any use in the past 30-day (yes/no).

Participants were asked to report “what percentage of your cigarette smoking episodes occurred under the influence of alcohol” and “does your pleasure from smoking cigarettes change when you are drinking alcohol” (range =1 [“strong decrease”] to 9 [“strong increase”]) based on McKee et al. (2004). These questions were adapted for marijuana.

Data Analysis

Among cigarette smokers who used marijuana and alcohol, extent of co-use (smoking cigarettes under the influence of alcohol or marijuana) and perceived pleasure from smoking cigarettes when drinking alcohol or using marijuana were compared using paired samples t-tests. Perceived pleasure from smoking cigarettes when drinking alcohol or using marijuana were each tested against the null hypothesis (5 = “no increase or decrease in pleasure”). Participants were also grouped based on frequency of binge drinking in the past month (non-binge, 1–3 days, 4–8 days, or 9+ days) based on Gubner et al. (2016). Perceived pleasure from smoking cigarettes when drinking alcohol was compared across the binge drinking groups using ANOVAs.

To validate findings in the current study among cigarette smokers who used both marijuana and alcohol, results from these individuals were compared to cigarette smokers in the parent study who used only marijuana (n=54) or only alcohol (n=158). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Sample characteristics

The sample of cigarette smokers who used alcohol + marijuana (n=200) was 52.0% male, 68.0% White, with a mean age of 20.9 ±2.0 (Table 1). Racial/ethnic groups were dichotomized (White versus non-White) due to lack of power to examine more detailed group differences given the relative small sample size of non-White ethnic groups (3.5% African American, 16.0% multiracial). Participants smoked an average of 9.9 ±5.9 cigarettes per day on 6.6 ±0.9 days per week, and reported binge drinking on 4.3 ±5.5 days per month.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics of cigarette smokers based on alcohol and marijuana use in the past 30 days.

| Variable | Alcohol & marijuana (n=200) | Marijuana Only (n=54) | Alcohol Only (n=158) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, % Male | 52.0% | 55.6% | 38.2%** |

| Ethnicity, % white | 68.0% | 79.6% | 77.7% |

| Age | 20.9 ± 2.0 | 20.4 ± 2.1 | 21.1 ± 2.0 |

| Household income | - | - | - |

| < $20,000 | 23.0% | 33.3% | 29.7% |

| $21,000–$60,000 | 51.5% | 46.3% | 49.4% |

| $61,000–$100,000 | 18.5% | 14.8% | 13.3% |

| > $100,000 | 7.0% | 5.6% | 7.6% |

| Usual cigarettes/day | 9.9 ± 5.9 | 12.6 ± 5.4* | 11.1 ± 6.7 |

| Days/week smoke cigarettes | 6.6 ± 0.9 | 6.9 ± 0.4** | 6.7 ± 0.9 |

| Alcohol consumption | - | - | - |

| Never | 0.0% | 100% | 0.0% |

| Monthly or less | 36.0% | - | 34.2% |

| 2–4 times a month | 36.5% | - | 39.2% |

| 2–3 time/week | 19.0% | - | 17.1% |

| 4 or more times/week | 8.5% | - | 9.5% |

| Typical drinks/day | - | - | - |

| 0 | 59.5% | - | 60.1% |

| 1–2 | 21.0% | - | 20.3% |

| 3–4 | 11.0% | - | 8.2% |

| 5 or more | 8.5% | - | 11.4% |

| Binge drinking days/month | 4.3 ± 5.5 | - | 4.1 ± 6.0 |

| Used marijuana in the Past month | 100% | 100% | 0.0% |

Shown are the % or Mean ± SD for the study sample. Binge drinking was defined as 4 or more alcoholic standard drinks for women, 5 or more alcoholic standard drinks for men. Continuous variables were compared using t-tests, categorical variables using Chi2-tests. Significant differences between cigarettes smokers who only use marijuana or only drink alcohol compared to the alcohol + marijuana user are indicated;

p < .05;

p < .01.

Cigarette smokers who used alcohol + marijuana were compared to cigarette smokers who only used alcohol or only used marijuana on baseline characteristics (Table 1). Cigarette smokers who only used alcohol were significantly more likely to be female compared to cigarette smokers who used alcohol + marijuana (χ2(1) =7.0; p=0.008). There were no other differences for tobacco use or alcohol use characteristics between groups. Cigarette smokers who only used marijuana smoked more cigarettes per day (t(356) =2.61, p=0.01) and smoked cigarettes on more days per week (t(356) =3.37, p=0.001) than smokers who used alcohol + marijuana.

Extent of and pleasure from cigarette smoking with alcohol versus marijuana

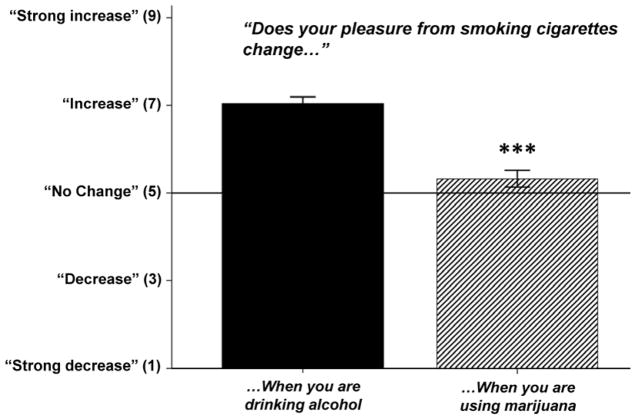

Among smokers who used alcohol + marijuana, a similar percentage of overall cigarettes smoked was reported under the influence of alcohol (42.4% ±31.2%) compared to marijuana (43.1% ±30.0%; t(199)= −0.26, p=0.79). Perceived pleasure from smoking cigarettes was greater when drinking alcohol compared to using marijuana (t(199) =7.05, p<0.001; Figure 1). Individuals reported an increase in perceived pleasure from smoking cigarettes when drinking alcohol (7.0 ±2.2 versus null hypothesis 5=“no increase or decrease in pleasure”; t(199) =13.0, p<0.001). In contrast, there was on average no change in perceived pleasure from smoking cigarettes when using marijuana (5.3 ±2.7, t(199)=1.7, p=0.09). Perceived pleasure from smoking cigarettes did not differ by frequency of binge drinking (F(3,200)=0.84, p=0.47): non-binge (7.1 ±2.1), 1–3 binge days (6.8 ±2.3), 4–8 binge days (7.0 ±2.1), 9+ binge days (7.6 ±2.2).

Figure 1.

Among cigarette smokers who drink alcohol and use marijuana (n=200) there was an increase in perceived pleasure from smoking cigarettes when drinking alcohol (left) but not when using marijuana (right). ***: p < 0.001 for the comparison of perceived pleasure from smoking cigarettes after alcohol versus marijuana using a paired samples t-test.

Comparison of the alcohol + marijuana smokers to alcohol only or marijuana only smokers

There were no differences between smokers who used both alcohol + marijuana (n=200) and smokers who used only alcohol (n=154) on the percentage of cigarettes reported under the influence of alcohol (t(357)=0.94, p=0.35) or perceived pleasure from smoking cigarettes when drinking alcohol (t(357)=0.15, p=0.88). There were similarly no differences between smokers who used alcohol + marijuana compared to smokers who used only marijuana (n=54) on percentage of cigarettes under the influence of marijuana (t(252)= 0.29, p=0.77) or perceived pleasure from smoking cigarettes when using marijuana (t(252)=1.0, p=0.32 ).

Discussion

Among a sample of young adult cigarette smokers who used both alcohol and marijuana in the past month, a similar proportion of cigarette smoking episodes were reported under the influence of alcohol and marijuana. In contrast, perceived pleasure from smoking cigarettes was only reported to increase when drinking alcohol but not when using marijuana. There were no differences between smokers who used alcohol + marijuana compared to smokers who used only marijuana or only alcohol on these measures, increasing the validity of the findings.

Tobacco and alcohol have been found to have combined pharmacological effects that result in greater reward (Glautier et al. 1996; McKee et al. 2004; Perkins et al. 1995; Rose et al. 2004). In contrast, marijuana and cigarettes may be co-used primarily for reasons other than increased pleasure. For example, nicotine may attenuate some of the cognitive impairments induced by acute or chronic marijuana use (Viveros et al. 2006) and it has been suggested that nicotine may attenuate the sedative effects of marijuana (Ream et al. 2008). A recent qualitative study examining the effects of cigarette smoking on the perceived effects of marijuana use found certain individuals reported smoking cigarettes to intensify the marijuana high, while others reported not liking the combined effects as it made them feel dizzy or nauseous (Schauer et al., 2016). Combined effects of marijuana use and cigarette smoking seem to vary by user, and may not be as uniform as the combined effects of alcohol and cigarettes.

Since the main route of administration for marijuana is smoking, some aspects of marijuana use (e.g., smoke, lighting of a joint, throat feeling when inhaling smoke) may serve as cues that increase urges to smoke cigarettes (Agrawal et al. 2012; Shadel et al. 2004; Veilleux & Skinner 2015). In addition certain individuals may enjoy aspects of smoking in general, regardless of substance (Schauer et al., 2016). Previous studies have found that urges to use marijuana and tobacco were correlated among young adults (Ramo et al. 2014) and that using tobacco subsequent to marijuana (called “chasing”) is a common pattern of use (Ream et al. 2008). The primary route of marijuana administration is smoking, often mixed with tobacco (Baggio et al., 2014). Route of marijuana administration could play a role in differences in perceived pleasurable effects of smoking cigarettes when using marijuana. Research is needed to compare reasons for use and effects of cigarette smoking between different routes of marijuana administration (e.g. smoking, vaping, or eating).

Both the non-binge drinkers and all binge drinking frequency groups reported an increase in perceived pleasure from smoking cigarettes when drinking alcohol, suggesting that frequency of binge drinking and binge drinking itself may not be essential to the relationship between enhanced pleasure from smoking during alcohol consumption. Greater pleasurable effects of smoking cigarettes when drinking alcohol may occur with lower levels of alcohol consumption. Alcohol has biphasic stimulant and sedative effects, and nicotine has been found to attenuate the sedative/hypnotic effects of heavy alcohol consumption (Perkins et al. 2000, Ralevski et al. 2012). Attenuation of sedative effects may be a motivation for the co-use of tobacco and alcohol most relevant to binge drinking.

Limitations

There are several limitations of this work. We used retrospective self-reported data which may be biased and cannot establish a causal inference between alcohol and marijuana use and perceived pleasure from smoking cigarettes. Laboratory-based human pharmacology studies or intensive longitudinal event-level designs (e.g., Ecological Momentary Assessment), are needed to replicate our findings and advance this area of research. We did not assess the overlap between cigarettes smoked when both drinking alcohol and using marijuana, mode of marijuana use (e.g., smoked, vaporized, digested), or marijuana use frequency. This last limitation is especially important, since the relationships between marijuana and tobacco use and reasons for co-use may vary as a function of frequency of use (Schauer et al., 2016). We also focused exclusively on the enhancement of perceived pleasure of smoking cigarettes by alcohol or marijuana rather than the ability of cigarettes to enhance the pleasurable effects of other substances. Previous work by McKee et al. (2004) suggests the direction we assessed was likely to be more affected, with individuals deriving more pleasure from smoking cigarettes while drinking compared to pleasure from drinking alcohol when smoking cigarettes (McKee et al., 2004). It should be noted that we asked participants to distinguish pleasurable effects of smoking cigarettes from effects of other psychoactive substances (alcohol and marijuana) they co-used and we do not know how well participants were able to reliably do this. However differences in the reported pleasurable effects of alcohol on cigarettes compared to cigarettes on alcohol suggest that individuals are able to differentiate the effects of one substance on another (McKee et al., 2004). Future studies might also investigate reasons for and expectancies of substance co-use in addition to perceived pleasure (Montgomery & Ramo, 2017; Ramo et al., 2013; Rohsenow et al., 2005; Schauer et al., 2016). Lastly, our sample comprised young adult smokers participating in a Facebook smoking cessation intervention, which may limit the generalizability of the results; however given that 90% of all US young adults use social media (Perrin et al. 2015), this concern is limited.

Conclusions

Retrospective self-reported perceived pleasure from smoking cigarettes was greater when drinking alcohol versus when using marijuana. There may be important differences in why cigarettes are co-used with alcohol compared to marijuana and how pleasure from co-use is perceived. Targeting the increased pleasure from smoking cigarettes when drinking alcohol could enhance effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions among young adults who drink alcohol, regardless of binge drinking frequency or marijuana use. In contrast, it may be more important to target other reasons for co-use of tobacco and marijuana.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was supported by the NIH National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA, K23 DA032578 and P50 DA09253). The preparation of this manuscript was supported by the NIDA (T32 DA007250; F32 DA042554), and the California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (TRDRP, 25FT-0009). The funding sources had no involvement in the study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Agrawal A, Budney AJ, Lynskey MT. The co-occurring use and misuse of cannabis and tobacco: a review. Addiction. 2012;107:1221–1233. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03837.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Silberg JL, Lynskey MT, Maes HH, Eaves LJ. Mechanisms underlying the lifetime co-occurrence of tobacco and cannabis use in adolescent and young adult twins. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2010;108:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Lynskey MT. Tobacco and cannabis co-occurrence: does route of administration matter? Drug and alcohol dependence. 2009;99:240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amos A, Wiltshire S, Bostock Y, Haw S, McNeill A. ‘You can’t go without a fag... you need it for your hash’—a qualitative exploration of smoking, cannabis and young people. Addiction. 2004;99:77–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggio S, Deline S, Studer J, Mohler-Kuo M, Daeppen JB, Gmel G. Routes of administration of cannabis used for nonmedical purposes and associations with patterns of drug use. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54:235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balfour DJK, Ridley DL. The effects of nicotine on neural pathways implicated in depression: A factor in nicotine addiction? Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 2000;66:79–85. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00205-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo JK, Husten C. Sociocultural influences on smoking and drinking. Alcohol Research and Health. 2000;24:225–232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb NK, Graham AL, Bock BC, Papandonatos G, Abrams DB. Initial evaluation of a real-world Internet smoking cessation system. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2005;7:207–216. doi: 10.1080/14622200500055319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JW, Fucito LM, Piasecki TM, Piper ME, Schlam TR, Berg KM, Baker TB. Relations of alcohol consumption with smoking cessation milestones and tobacco dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:1075. doi: 10.1037/a0029931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani JA, Harris RA. Nicotine addiction and comorbidity with alcohol abuse and mental illness. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1465–1470. doi: 10.1038/nn1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk DE, Yi HY, Hiller-Sturmhöfel S. An epidemiologic analysis of co-occurring alcohol and tobacco use and disorders: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Alcohol Res Health. 2006;29:162–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamaleddin I, Wertheim C, Zhu AZ, Coen KM, Vemuri K, Makryannis A, Goldberg SR, Le Foll B. Cannabinoid receptor stimulation increases motivation for nicotine and nicotine seeking. Addict Biol. 2012;17:47–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glautier S, Clements K, White JA, Taylor C, Stolerman IP. Alcohol and the reward value of cigarette smoking. Behavioral Pharmacology. 1996;7:144–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubner NR, Delucchi KL, Ramo DE. Associations between binge drinking frequency and tobacco use among young adults. Addictive Behavior. 2016;60:191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SM, Tsoh JY, Prochaska JJ, Eisendrath S, Rossi JS, Redding CA, et al. Treatment for cigarette smoking among depressed mental health outpatients: a randomized clinical trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1808–1814. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.080382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison EL, McKee SA. Non-daily smoking predicts hazardous drinking and alcohol use disorders in young adults in a longitudinal US sample. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2011;118:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizink AC, Levälahti E, Korhonen T, Dick DM, Pulkkinen L, Rose RJ, Kaprio J. Tobacco, cannabis, and other illicit drug use among Finnish adolescent twins: causal relationship or correlated liabilities? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:5–14. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignatowska-Jankowska BM, Muldoon PP, Lichtman AH, Damaj MI. The cannabinoid CB2 receptor is necessary for nicotine-conditioned place preference, but not other behavioral effects of nicotine in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2013;229:591–601. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3117-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansma JM, van Hell HH, Vanderschuren LJ, Bossong MG, Jager G, Kahn RS, Ramsey NF. THC reduces the anticipatory nucleus accumbens response to reward in subjects with a nicotine addiction. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3:e234. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, McKee SA, Toll BA, Krishnan-Sarin S, Cooney JL, Makuch RW, O’Malley SS. Risk factors for treatment failure in smokers: relationship to alcohol use and to lifetime history of an alcohol use disorder. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10:1793–1809. doi: 10.1080/14622200802443742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingford-Hughes A, Nutt D. Neurobiology of addiction and implications for treatment. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;182:97–100. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.2.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay HG, Danaher BG, Seeley JR, Lichtenstein E, Gau JM. Comparing two web-based smoking cessation programs: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2008;10:e40. doi: 10.2196/jmir.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee SA, Hinson R, Rounsaville D, Petrelli P. Survey of subjective effects of smoking while drinking among college students. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6:111–117. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001656939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery L, Ramo DE. What Did You Expect?: The Interaction Between Cigarette and Blunt vs. Non-Blunt Marijuana Use among African American Young Adults. Journal of Substance Use. 2017 doi: 10.1080/14659891.2017.1283452. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete F, Rodríguez-Arias M, Martín-García E, Navarro D, García-Gutiérrez MS, Aguilar MA, Aracil-Fernández A, Berbel P, Miñarro J, Maldonado R, Manzanares J. Role of CB2 cannabinoid receptors in the rewarding, reinforcing, and physical effects of nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:2515–2524. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ. Is there a common molecular pathway for addiction? Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1445–1449. doi: 10.1038/nn1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, NIAAA. NIAAA Council approves binge drinking definition. NIAAA Newsletter. 2004;3:3. [Google Scholar]

- Nichter M, Nichter M, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Flaherty B, Carkoglu A, Taylor N. Gendered dimensions of smoking among college students. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2006;21:215–243. [Google Scholar]

- Oleson EB, Cheer JF. A brain on cannabinoids: the role of dopamine release in reward seeking. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2012;2:a012229. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panlilio LV, Zanettini C, Barnes C, Solinas M, Goldberg SR. Prior exposure to THC increases the addictive effects of nicotine in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:1198–1208. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Sawyer SM, Wakefield M. Teen smokers reach their mid twenties. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Sexton JE, DiMarco A, Grobe JE, Scierka A, Stiller RL. Subjective and cardiovascular responses to nicotine combined with alcohol in male and female smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;119:205–212. doi: 10.1007/BF02246162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Fonte C, Grobe JE. Sex differences in the acute effects of cigarette smoking on the reinforcing value of alcohol. Behav Pharmacol. 2000;11:63–70. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200002000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin A. Pew Research Center; 2015. [Accessed Nov 18, 2016]. Social Networking Usage: 2005–2015. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/10/08/2015/Social-Networking-Usage-2005-2015. [Google Scholar]

- Peters EN, Budney AJ, Carroll KM. Clinical correlates of co-occurring cannabis and tobacco use: A systematic review. Addiction. 2012;107:1404–1417. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03843.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralevski E, Perry EB, Jr, D’Souza DC, Bufis V, Elander J, Limoncelli D, Vendetti M, Dean E, Cooper TB, McKee S, Petrakis I. Preliminary findings on the interactive effects of IV ethanol and IV nicotine on human behavior and cognition: a laboratory study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14:596–606. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo DE, Thrul J, Delucchi KL, Ling PM, Hall SM, Prochaska JJ. The Tobacco Status Project (TSP): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial of a Facebook smoking cessation intervention for young adults. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:897. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2217-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo DE, Delucchi KL, Liu H, Hall SM, Prochaska JJ. Young adults who smoke cigarettes and marijuana: Analysis of thoughts and behaviors. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo DE, Liu H, Prochaska JJ. Validity and reliability of the nicotine and marijuana interaction expectancy (NAMIE) questionnaire. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131:166–70. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo DE, Prochaska JJ. Prevalence and co-use of marijuana among young adult cigarette smokers: An anonymous online national survey. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2012;7:1. doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo DE, Liu H, Prochaska JJ. Tobacco and marijuana use among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review of their co-use. Clinical Psychology Review. 2012a;32:105–121. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo DE, Liu H, Prochaska JJ. Reliability and validity of young adults’ anonymous online reports of marijuana use and thoughts about use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012b;26:801–811. doi: 10.1037/a0026201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo DE, Hall SM, Prochaska JJ. Reliability and validity of self-reported smoking in an anonymous online survey with young adults. Health Psychology. 2011;30:693–701. doi: 10.1037/a0023443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ream GL, Benoit E, Johnson BD, Dunlap E. Smoking tobacco along with marijuana increases symptoms of cannabis dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;95:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow DJ, Colby SM, Martin RA, Monti PM. Nicotine and other substance interaction expectancies questionnaire: relationship of expectancies to substance use. Addict Behav. 2005;30:629–641. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JE, Brauer LH, Behm FM, Cramblett M, Calkins K, Lawhon D. Psychopharmacological interactions between nicotine and ethanol. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:133–144. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001656957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer GL, Hall CD, Berg CJ, Donovan DM, Windle M, Kegler MC. Differences in the relationship of marijuana and tobacco by frequency of use: A qualitative study with adults aged 18–34 years. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2016;30:406–414. doi: 10.1037/adb0000172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadel WG, Niaura R, Abrams DB. Thinking about craving: an experimental analysis of smokers’ spontaneous self-reports of craving. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:811–815. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromberg P, Nichter M, Nichter M. Taking play seriously: Low-level smoking among college students. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2007;31:1–24. doi: 10.1007/s11013-006-9042-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) [Accessed Nov 18, 2016];Detailed Data Table 6.9B - Types of Illicit Drug Use in the Past Month among persons aged 18 to 25, by Past Month Cigarette Use: Percentages, 2013 and 2014. 2014 http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs2014/NSDUH-DetTabs2014.htm#tab6-9b.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) [Accessed Nov 18, 2016];Detailed Data Table 6.30B - Tobacco Product Use in the Past Month among Persons Aged 18 to 25, by Levels of Past Month Alcohol Use: Percentages, 2013 and 2014. 2014 http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs2014/NSDUH-DetTabs2014.htm#tab6-26b.

- Swartz LH, Noell JW, Schroeder SW, Ary DV. A randomised control study of a fully automated internet based smoking cessation programme. Tobacco Control. 2006;15:7–12. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.006189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Mitchell JM, Besson MJ, Caboche J, Maldonado R. Behavioural and biochemical evidence for interactions between Delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol and nicotine. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135:564–578. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veilleux JC, Skinner KD. Smoking, food, and alcohol cues on subsequent behavior: A qualitative systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2015;36:13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viveros MP, Marco EM, File SE. Nicotine and cannabinoids: parallels, contrasts and interactions. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:1161–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman ER, Chen YY. The co-occurrence of smoking and drinking among young adults in college: national survey results from the United States. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2005;80:377–386. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SE, Rhee SH, Stallings MC, Corley RP, Hewitt JK. Genetic and Environmental Vulnerabilities Underlying Adolescent Substance Use and Problem Use: General or Specific? Behavior Genetics. 2006;36:603–615. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]