Abstract

Many interventions targeting cognitive skills or socioemotional skills and behaviors demonstrate initially promising but then quickly disappearing impacts. Our paper seeks to identify the key features of interventions, as well as the characteristics and environments of the children and adolescents who participate in them, that can be expected to sustain persistently beneficial program impacts. We describe three such processes: skill-building, foot-in-the-door and sustaining environments. We argue that skill-building interventions should target “trifecta” skills – ones that are malleable, fundamental, and would not have developed eventually in the absence of the intervention. Successful foot-in-the-door interventions equip a child with the right skills or capacities at the right time to avoid imminent risks (e.g., grade failure or teen drinking) or seize emerging opportunities (e.g., entry into honors classes). The sustaining environments perspective views high quality of environments subsequent to the completion of the intervention as crucial for sustaining early skill gains. These three perspectives generate both complementary and competing hypotheses regarding the nature, timing and targeting of interventions that generate enduring impacts.

Keywords: interventions, fadeout, methodology

I. INTRODUCTION

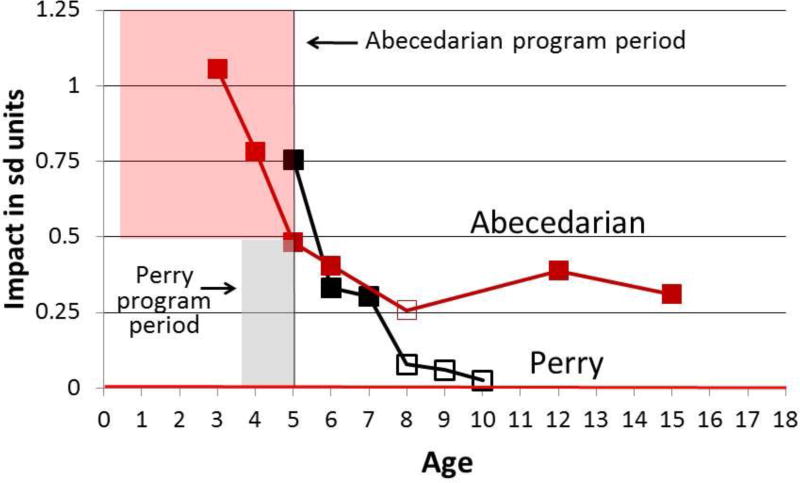

Far too often, impacts on outcomes targeted by intervention designers soon disappear. This is readily apparent in interventions begun in early childhood, with perhaps the most famous example being Perry Preschool, where the program’s large end-of-treatment impact on IQ (.75 sd) at age 5 had dropped to a statistically insignificant .08 sd by age 8 (Schweinhart et al. 2005; Figure 1). More generalizable – and worrisome – is the finding by Puma et al. (2012), based on a random assignment of 4,442 children to a national sample of Head Start centers, of noteworthy impacts at the end of the Head Start year, but virtually no statistically significant impacts on any cognitive skill or socioemotional skill or behavior over the next several years. On the other hand, a second famous early childhood intervention begun a decade after Perry—the Abecedarian Project—generated IQ impacts that persisted well beyond age 8 (Campbell, Pungello, Miller-Johnson, Burchinal, & Ramey, 2001; also shown in Figure 1). Both Perry and Abecedarian produced substantial favorable impacts in adulthood, although not always on the same outcomes.

Figure 1.

IQ impacts in Perry and Abecedarian

Solid marker denotes p<.05. IQ impacts are based on national norms

Examining this and other seemingly contradictory evidence on fadeout, we seek to identify the key features of child and adolescent interventions, as well as the characteristics and environments of their participants, that can be expected to generate persistent program impacts. We will speak of impacts on “skills” but use that term broadly to encompass any skill, behavior, capacity or psychological resource that helps individuals attain successful outcomes.1 With some disciplines most comfortable with the term “noncognitive skill” and others most comfortable with some variant of “socioemotional skill or behavior,” we have opted to use the two sets of terms interchangeably.

We integrate findings from across multiple disciplines by using a very broad definition of skills, but where appropriate, provide examples of the specific socio-emotional, behavioral or cognitive skill targeted by the intervention. We consider interventions that are quite diverse in terms of their setting (both within and outside of classrooms), timing (encompassing various stages of childhood and adolescence) and populations (mostly at-risk children and adolescents in the United States but with some interventions offered to both at-risk and more advantaged populations).

We begin in Section II with a selective review of evidence on fadeout, choosing our examples to illustrate the diverse patterns of fadeout across outcomes within and across interventions. We then formulate three distinct processes that might sustain benefits for children and adolescents: skill building, foot-in-the-door skill or capacity boosts, and sustaining environments. While we acknowledge the benefits of short term positive impacts of childhood interventions, the focus of our paper is primarily on intervention impacts that demonstrate longer-term persistence across multiple years.

As detailed in Section III, the skill-building perspective undergirds most cognitive theories of math and literacy learning. One version of it has been formalized in economists’ human capital model of the skill accumulation process. Key to skill building is that simpler skills support the learning of more sophisticated ones and, in the economic models, that skills acquired prior to a given skill- or capacity-building intervention increase the productivity of that investment.

Our main contribution here is to argue for the importance in this skill-building perspective of what we call “trifecta” skills – ones that are malleable, fundamental and would not have developed in the absence of the intervention. We argue that all three conditions are needed to generate long-run effects, which limits substantially the kinds of interventions that might be expected to produce persistent benefits to children and adolescents. In the case of early childhood interventions, the third trifecta condition – eventual skill development in counterfactual conditions – is particularly problematic for interventions that build early literacy or math skills because most children are likely to eventually acquire at least minimal levels of these skills soon after entering school. Indeed, much of the ‘fade-out’ effects of early childhood interventions have been attributed to this type of catch up among the larger population of children.

As explained in Section IV, developmental timing is key to the foot-in-the-door, perspective. Successful foot-in-the-door interventions equip a child with the right skills or capacities at the right time to avoid imminent risks (e.g., grade failure, teen drinking or teen childbearing) or to seize emerging opportunities (e.g., entry into honors classes, SAT prep). The skill or capacity boosts need not be permanent, as with SAT prep that boosts chances of acceptance into a higher-resourced college, a key step in a positive cascade that might influence human capital and labor market outcomes. For SAT prep, it is the enriched college resources, rather than any lingering test prep knowledge, that leads to a higher-paying job.

A third approach to understanding fadeout is what we call the “sustaining environments” perspective (Section V). It recognizes the importance of interventions that build important skills and capacities, but views the quality of environments subsequent to the completion of the intervention as crucial for maintaining initial skill advantages. Section VI summarizes some of the implications of our analysis.

II. PATTERNS OF FADEOUT AND PERSISTENCE

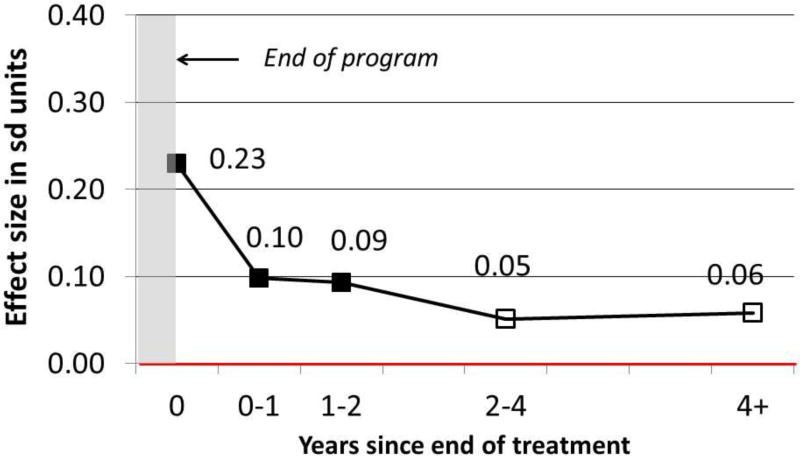

Original calculations, using information from a meta-analytic database of the evaluations of 67 high-quality early childhood education (ECE) interventions published between 1960 and 2007, produce the pattern of geometrically declining effect sizes shown in Figure 2 for cognitive outcomes.2 At the end of the programs, effect sizes averaged .23 standard deviations – considerably smaller than the end-of-treatment impacts shown for Perry and Abecedarian in Figure 1. Post-treatment impacts measured no more than 12 months after the end of treatment had dropped by more than half, to .10 sd, and again by half one to two years later. Figure 1 shows that while Perry’s IQ impacts approximate a geometric decline, Abecedarian’s IQ impacts were much more persistent (although they did decline substantially during the treatment period), which suggests that fadeout patterns based on cross-study average impacts are likely to conceal study-to-study variation.

Figure 2.

Cognitive impacts in 67 ECE studies

Solid marker denoted p<.05.

Most interventions targeting children’s cognitive, social or emotional development fail to follow their subjects beyond the end of their programs (e.g., Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor, & Schellinger, 2011; Smit, Verdurmen, Monshouwer, & Smit, 2008).3 When they do, complete fadeout is common. As mentioned above, Puma et al. (2012) found virtually no statistically significant impacts of Head Start on either cognitive or noncognitive measures in kindergarten, first or second grades. That said, Deming’s (2009) sibling-based analysis shows that while initial impacts of Head Start on achievement in the early grades had faded to statistical insignificance by early adolescence, a number of significant differences in attainment and behavioral domains were detected in early adulthood.

A number of mathematics interventions for preschool or school-aged children also generate impressive initial effects that have been found to fade over time (Clements, Sarama, Wolfe, & Spitler, 2013; Smith, Cobb, Farran, Cordray, & Munter, 2013). Bus & van IJzendoorn’s (1999) meta-analysis of early phonological awareness training found substantial effects on children’s initial reading skills (.44 sd) but much smaller effects on reading skills (.16 sd) in the subset of studies with a follow-up assessment 18 months, on average, after the completion of the programs. Unfortunately, none of these studies includes longer-term follow up information.

In some long-run studies such as Perry and Abecedarian, initial fadeout is followed by the detection of impacts in adulthood, although not always on the same kinds of developmental outcomes. In the case of teacher effects, Jacob, Lefgren and Sims (2010) conclude that teacher-induced (value-added) learning and other measures of teacher quality have low persistence, with three-quarters or more of teaching-year effects fading out within one year. However, Chetty, Friedman and Rockoff (2014) found longer-run impacts on both attainment and behavior in the same children when participants were tracked through adulthood via administrative records (but see Rothstein, 2015, for a critical review).

A pattern of fadeout and reemergence in young adulthood has also been documented for early social skills training. The Fast Track program provided a range of behavioral and academic services to a random subset of 1st grade boys exhibiting conduct problems. Impacts in elementary school were uniformly positive, producing improvements in the boys’ prosocial behaviors and classroom social competence and reductions in their aggressive and oppositional behaviors (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1999a, 1999b). By middle or high school, most of these effects had disappeared for all but the highest-risk boys (CPPRG, 2011), although impacts on some of these outcomes reappeared when the participants were assessed in their mid-20s (Dodge et al., 2015).

All in all, it appears that some well-designed and implemented cognitive, social and emotional interventions produce immediate impacts on child and adolescent outcomes. Sharp reductions in subsequent intervention effects are typically observed among the regrettably small fraction of interventions where follow-up data are available. And, in a handful of some of the most rigorously implemented and evaluated early childhood interventions, this pattern of rapid intervention-effect fadeout has been followed by the detection of impacts on attainment, behavior and sometimes health in adulthood.

III. SKILL-BUILDING MODELS

How can we account for these patterns of fadeout and persistence in child and adolescent interventions? The next three sections draw from the limited conceptual literature on fadeout to formulate three distinct processes that may explain persistence and fade-out of intervention effects over time – skill building, foot-in-the-door capacity boosts needed to respond to windows of opportunity or risk across childhood and adolescence, and sustaining environments. And while short-term impacts of interventions can be beneficial (e.g., by reducing school districts’ expenditures on special education programs), our paper also concentrates to the extent possible on longer-run impacts that are detected years, and sometimes decades, after the intervention has ended.

Skill building processes are most easily seen in the case of math and literacy, where early academic skills are the foundations upon which later skills are built. Counting serves as a causal basis for children’s early addition problem solving, and addition is often employed as a subroutine of children’s multiplication problem solving (Baroody, 1987; Clements & Sarama, 2004, 2014; Lemaire & Siegler, 1995). In the development of children’s reading skills, children’s ability to match letters to sounds supports their learning to recognize written words, which in turn supports their vocabulary learning, which then supports their reading comprehension (LaBerge & Samuels, 1974). Such relations are likely bidirectional, where basic skills are also practiced during the learning of more advanced skills (Stanovich, 1986).

Skill-building economic models of human development formalize thinking about the human capital production function and emphasize how investments and child endowments interact to create a child’s accumulating stock of human capital. Cunha and Heckman (2007) describe a cumulative model of the production of human capital that, as summarized in their phrase “skill begets skill,” results from two distinct processes. First is “self-productivity” – the process described above for math and literacy by which more complicated skills develop from simpler ones. This insight supports the idea that intervention impacts may be particularly likely to persist when interventions are designed to build skills incrementally within any given developmental domain. An example would be a math intervention teaching the number line that facilitates the learning of higher-level math skills in later grades (Siegler, 2009).

Cunha and Heckman (2007; also see Ceci & Papierno, 2005) also introduce the concept of “dynamic complementarity,” the idea that skills acquired prior to a given human capital investment increase the productivity of that investment. Thus, for example, children who enter school with the strongest cognitive skills and socioemotional skills and behaviors are assumed to profit most from K-12 schooling by, say, learning more from classroom instruction or being selected for gifted and talented programs in the early grades or for honors or AP classes in high school. Although this synergy between initial skills and later interventions may be observed for universal interventions such as K-12 schooling, it is less likely to hold for targeted programs such as Head Start, which have an explicit compensatory purpose (Purtell and Gershoff, 2013, but see also Aizer and Cunha, 2012).

The Cunha and Heckman model predicts greater impact persistence of early human capital interventions when the intervention: i) boosts skills that are important for the production of later skills, and/or ii) boosts skills that best increase the productivity of later investments. The key intervention implication in this skill building model is the need to identify fundamental cognitive and noncognitive skills, capacities, behaviors or beliefs and develop them as early and efficiently as possible. Under this model, the quality of subsequent learning environments (e.g., K-12 schooling) may affect a child’s eventual level of skills, but the skill gap between treatment and control-group children resulting from an effective early childhood intervention ought to be maintained or even widen with time under a range of subsequent environmental conditions.

Trifecta Skills in the Context of the Skill Building Model

Cunha and Heckman (2007) speak generally of cognitive and noncognitive skills, but do not identify which skills matter the most. We propose that to provide persistent intervention-generated benefits for children, the skills, behaviors, capacities or beliefs targeted by interventions must share three key features: they are malleable through intervention, they are fundamental for success, and they would not develop eventually in most counterfactual conditions. Although we sometimes refer to each of these criteria as though it were dichotomous, it is more accurate to view each as continuous and varying within and across individuals, depending on age, other personal characteristics, and circumstances. We also do not mean to imply that “less malleable” skills, behaviors, capacities, and beliefs are completely immutable. And because counterfactual conditions are often less conducive for healthy development for “at risk” populations, our trifecta skill analysis is particularly relevant for interventions targeting disadvantaged children and adolescents.

Our characterization of these skills as “trifecta” connotes the importance of meeting all three criteria, which we argue limits substantially the kinds of skills that interventions can target productively. Trifecta skills may be influenced directly, as by an intervention (e.g., direct classroom instruction) designed to influence children’s skill development, or indirectly, as through an intervention that changes children’s environments (e.g., targeting parent-child relationships, neighborhood and school safety) in ways that promote their fundamental skills.

Malleability and fundamentality

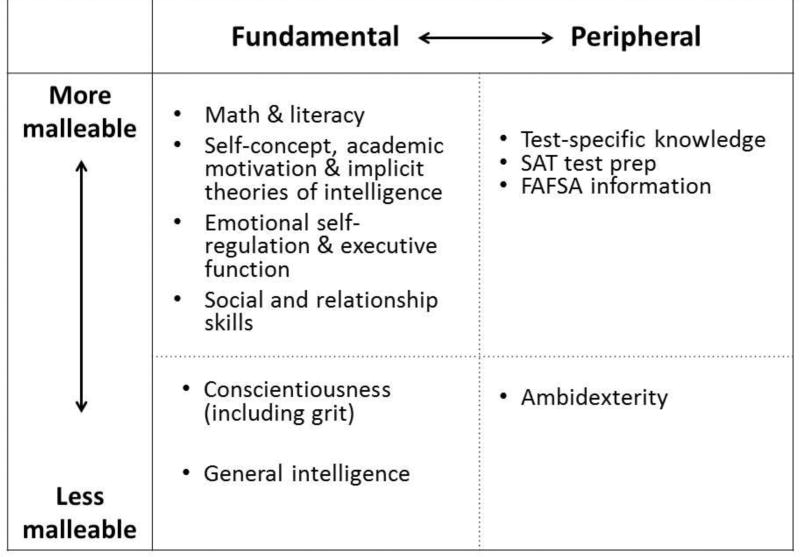

Setting aside for the moment a consideration of counterfactual conditions, we posit that to provide lasting benefits for children, interventions must target skills, behaviors or beliefs that can be changed (malleability) and are crucial for achieving the desired outcomes (fundamentality). We define fundamental skills as those upon which later skills are built, and which influence positive life outcomes, such as attainment or labor market success. These long-term impacts may be direct effects of persistent skill gains (e.g., trained vocational skills may be rewarded in the labor market) or indirect effects of early skill gains via their effects on other skills (e.g., an early boost in English language proficiency may allow some children to learn more science, which may be rewarded in the labor market). As we discuss below, not all skills that generate positive long-run outcomes are “fundamental” because they may work indirectly through, for example, developmental cascades rather than skills themselves. Figure 3 categorizes a variety of child and adolescent skills, capacities, beliefs and characteristics according to their malleability and fundamentality. We begin our discussion in the lower left-hand quadrant, which contains fundamental but not readily malleable skills.4

Figure 3.

Fundamentality and malleability in skills, behaviors and beliefs

Fundamental but not readily malleable

Since it supports performance across a wide variety of important tasks, general intelligence, or g, is perhaps the best example of a “fundamental” capacity. General intelligence is the single strongest predictor of many measured traits and abilities, including occupational level and performance (Schmidt & Hunter, 2004), and strongly predicts other life outcomes as well (Herrnstein & Murray, 1994; Gottfredson, 1997; Heckman, 1995; Cawley, Conneely, Heckman, & Vytlacil, 1997).

Unfortunately, despite improvements in intelligence test performance across cohorts over time (Flynn, 2012) and research suggesting a larger role for environmental factors in the development of poor versus more affluent children’s cognitive skills (Tucker-Drob & Bates, 2016), attempts to boost general intelligence experimentally in individuals within the commonly observed range of intervention intensity and child characteristics have rarely proved successful (Jensen, 1998; but see Nisbett et al 2012 for a more optimistic review). Although performance on any particular intelligence test can be improved through training, some have argued that these gains rarely transfer broadly to cognitive performance in different domains (Haier, 2014; te Nijenhuis, van Vianen, & van der Flier, 2007), and tend to fade quickly after the conclusion of the intervention (Protzko, 2015). The existence of broad transfer resulting from cognitive training remains contested (see Au et al., 2015; Melby-Lervåg, Redick, & Hulme, 2016; Miles et al., 2016; Roberts et al., 2016).

The lack of consistent intervention impacts on children’s IQ has problematic implications for interventions seeking to improve this fundamental capacity, since it means that training designed to enhance performance on a specific cognitive skill or domain may be unlikely to enhance children’s general learning. As shown in Figure 1, at least one early childhood education intervention – Abecedarian – generated persistent effects on children’s IQ scores, perhaps because of the intense nature of the Abecedarian program, combined with the conditions of relative deprivation facing control group children and their families.

Conscientiousness – one of the “Big Five” personality traits identified by personality psychologists – is also likely to be fundamental.5 Conscientiousness reflects the propensity to be self-controlled, responsible to others, hardworking, orderly, and rule abiding (Roberts, Krueger, Lejuez, Richards, & Hill, 2014) and is the most powerful correlate in the personality domain of later job performance (Judge, Higgins, Thoresen, & Barrick, 1999; Almlund, Duckworth, Heckman, & Kautz, 2011). It is also associated with other important outcomes, such as children’s grades in school, health behaviors and longevity (Bogg & Roberts, 2004; Friedman et al., 1993; Poropat, 2014).

Historically, individual differences in traits such as conscientiousness have been viewed as largely stable across time (McCrae et al., 2000; for a review see McAdams & Pals, 2006), with substantial continuity documented between childhood behavioral styles and personality in early adulthood (Caspi, 2003). Some evidence suggests that personality traits may be amenable to change, particularly during adolescence and young adulthood (Magidson et al., 2012; Roberts et al., 2006). A recent study following university undergraduates reported evidence from two studies that goals to change one’s personality caused changes in some personality traits during the semester, but goals to change conscientiousness were not associated with subsequent changes in conscientiousness in either study (Hudson & Fraley, 2015). Further research on personality change is certainly warranted, but currently there is little direct evidence from interventions demonstrating that broad personality characteristics such as conscientiousness are readily malleable.6

Malleable but peripheral

A second set of skills are malleable but peripheral (the upper right corner in Figure 3). A classic example is test-specific knowledge. Being able to identify a picture as a “blue house” might improve a young child’s score on an early intelligence assessment, but this piece of knowledge alone is unlikely to benefit a child’s later schooling or labor market success. Impacts from interventions that focus on improving children’s knowledge of a limited number of peripheral facts or test-specific test-taking skills will likely fade out quickly. Indeed, peripheral skill targeting of this kind has been proposed as an explanation for fadeout of IQ score effects produced by ECE interventions (Jensen, 1998).

That said, interventions targeting peripheral skills may still deserve intervention attention if those skills provide “foot-in-the-door” advantages linked to longer-run benefits. An example might be test prep that increases chances of admission to a four-year or higher-status college, which in turn leads to a higher-paying job. But the mechanisms that sustain this effect over time are unlikely to be a direct result of a peripheral test prep skill, making this example different from our formulation of skill building processes that sustain enduring treatment impacts. We discuss foot-in-the-door avenues for sustaining intervention impacts in Section IV.

Fundamental and malleable

The fourth and most promising quadrant of Figure 3 contains skills, behaviors or beliefs that have been – or may eventually be – shown to be both fundamental for later success and malleable through intervention. Examples listed in Figure 3 include academic skills, child-based social-cognitive behaviors and beliefs, and relation-based social and relationship skills.

The combination of fundamentality and malleability is most apparent in children’s early basic literacy and mathematics skills. As argued above, both of these early skills are fundamental for subsequent learning within and across achievement domains, and both can be effectively taught. Ample correlational evidence supports this skill-progression view of eventual learning; early academic skills are robust statistical predictors of children’s achievement much later in school, as well as of labor market outcomes (Duncan et al., 2007; Ritchie & Bates, 2013).

However, as can be seen from the fadeout pattern in Figure 2, ECE interventions targeting early mathematics or literacy skills, malleability and fundamentality alone do not guarantee impact persistence. Below we suggest that simple academic skills fail to meet a third trifecta skill condition – the absence of eventual development without the intervention.

Personality psychologists often make a distinction between hard-to-change dispositional traits (e.g., conscientiousness and other dimensions of the Big Five) and more malleable characteristic adaptations (McAdams and Pals, 2006). Characteristic adaptations include many motivational and socio-cognitive features of personality, such as beliefs, values, goals, plans, strategies, and developmental tasks, some of which are viewed as both fundamental and malleable (Kenthirarajah and Walton, 2015; Yeager & Walton, 2011) as well as more closely linked than dispositional traits to an intervention’s targeted outcome (Littlefield, Stevens, & Sher, 2014). For example, children’s understanding of their ability to learn is hypothesized to be both malleable and fundamental for academic achievement (Wilson & Linville, 1982, 1985), since students who encounter difficulties in school but attribute these difficulties to transitory factors may be more likely to persist in their efforts to succeed, compared with students who encounter difficulties in school and attribute them to their own persistent shortcomings. Such characteristic adaptations are also viewed as more context-specific than dispositional traits, and may express themselves differently in school versus family contexts.

Another set of capacities in the “malleable and fundamental” quadrant involve cognitive and emotional self-regulation, which have been defined as the “processes by which the human psyche exercises control over its functions, states, and inner processes” (Baumeister and Vohs 2004; Raver 2004). Emotional regulation includes the ability to control anger, sadness, joy and other emotional reactions, and early measures of it predict such behaviors as aggression and internalizing problems (Bridges, Denham, & Ganiban, 2004; Eisenberg et al., 2005). Positive preschool intervention impacts on emotional regulation are reported in Morris et al. (2014), while positive impacts for later socioemotional interventions are summarized in Durlak et al. (2011).

Cognitive and developmental psychologists have viewed executive functions as fundamental for children’s self-regulation and school readiness (Blair & Razza, 2007). Executive functions are fundamental capacities for problem solving and goal oriented behavior. The components of executive function – impulse control, working memory and the ability to shift between tasks – are basic cognitive processes required in the performance of many everyday activities (Miyake, Friedman, Emerson, Witzki, & Howerter, 2000). Moreover, some evidence suggests that performance on tasks measuring executive functions can be altered in early childhood and later through curricula such as Tools of the Mind, which teaches children strategies for becoming deliberate, self-regulated learners who are capable of relating well to fellow students and engaging in teacher-directed activities (Diamond & Lee, 2011; but see null effects for Tools reported in Morris et al., 2014).

Some believe that targeting executive functions skills in parents and/or children can play an important role in generating positive long-term outcomes for children. However, because these programs often contain multiple components (e.g., skills training for parents and children, after care academic support, school-level engagement), it is difficult to isolate the specific contribution of changes in children’s executive functions to intervention effects and persistence (Jacob & Parkinson, 2015).

Development in Counterfactual Conditions

Merely targeting malleable and fundamental skills is insufficient for generating persistent impacts because many of these skills are soon mastered by children in the comparison groups. Rudimentary academic skills develop quickly in counterfactual conditions. For example, on nationally normed reading and mathematics tests, children learn over a full standard deviation of material between kindergarten and first grade (Hill, Bloom, Black, & Lipsey, 2008).7 Thus, while these kinds of early cognitive skills may be among the most fundamental and malleable, the impacts of interventions that target them may fade out most quickly owing to the fact that virtually all children will eventually receive this instruction.

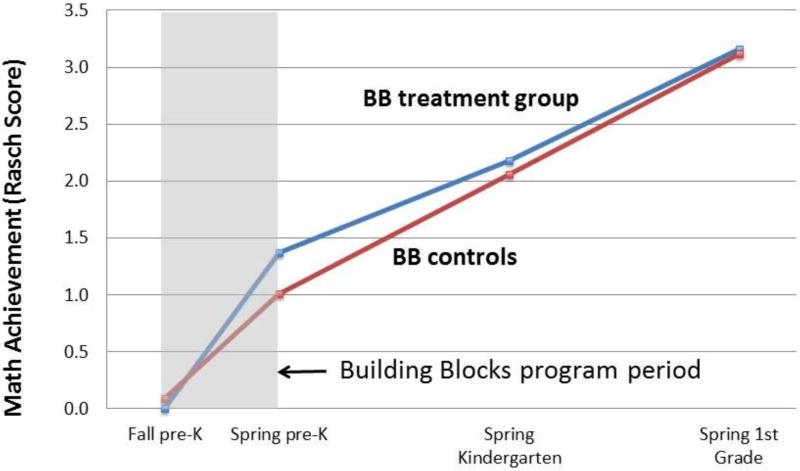

An example of fadeout caused by rapid growth among children in counterfactual conditions comes from Clements et al.’s (2013) TRIAD evaluation of the Building Blocks pre-K math intervention. Figure 4 shows that math achievement for children in the control group grew by nearly a full standard deviation between the fall and spring assessment points during the pre-K year, and then by about a full standard deviation in the annual intervals between spring of the pre-K year and spring of kindergarten as well as between the springs of kindergarten and first grade. Math achievement for children receiving the Building Blocks curriculum grew even faster – about .50 sd faster – than controls during the pre-K year, but not as quickly after that. The shrinking gap between the two groups after program completion reflects the fading of the program’s impacts after it ended, as well as the “catch up” among those in the control condition.

Figure 4.

Math Achievement During and After the Pre-K Building Blocks Program

Note: Rasch score standard deviation = 1

The distinction between skills that do and do not develop quickly in most counterfactual conditions is akin to Paris’s (2005) distinction between “constrained” and “unconstrained” reading skills and Ackerman’s (2007) distinction between “closed” and “open” tasks. Constrained and closed skills require only a limited amount of knowledge and are simple enough for virtually all individuals who practice them to master. Intervention-induced impacts on these kinds of skills fade out because children would have acquired them in any case. Accordingly, the strong predictive power of early academic skills, many of which fall into the “closed” category, for later academic achievement likely reflects individual differences in more fundamental skills or environments that influence learning across time, rather than a causal impact on later achievement of the rudimentary literacy or numeracy skills themselves. In contrast, mastery of open tasks, such as general mathematics achievement or vocabulary is always incomplete, so that even extensive practice still leaves room for improvement. More complex closed tasks, such as fraction arithmetic or knowledge of basic scientific principles, may also never reach expert levels for many children without interventions beyond normative K-12 schooling.

More sophisticated skills develop at different speeds depending on the counterfactual conditions, with the slowest growth occurring for the most complex skills in conditions faced by most “at risk” children. Thus, the nature of counterfactual conditions typically enhances the efficacy of interventions targeting more sophisticated skills for at-risk relative to more advantaged populations.

The moderation of malleability by counterfactual conditions has important implications for predicting which early intervention studies will show persistent effects on fundamental skills. Impacts from interventions that target children who face formidable environmental obstacles are likely to persist the longest owing to the environmental-induced problems facing children in the comparison groups.

Trifecta Skills, Behaviors and Beliefs

Which skills meet all three criteria – malleable, fundamental and unlikely to develop in the absence of the intervention? Our list, which should be viewed as tentative given the limited evidence that is currently available, includes advanced academic and concrete vocational skills as well as achievement-related beliefs and behaviors (Table 1). Owing to difficulties in meeting all three of our criteria, this list is not nearly as long as might be hoped and, in the top panel, includes almost nothing of relevance to early childhood education. In principle, we do not equate advanced skills with skills learned by children of more advanced ages and instead allow for the possibility that some skills learned by some very young children might never be mastered by most children a few years older. In practice, however, concrete examples of such skills elude us.

Table 1.

Possible “trifecta” skills

| Possible trifecta skills, beliefs or capacities by domain |

|---|

Academic skills

|

Beliefs, behaviors and capacities

|

|

|

| Additional trifecta skills for children in very adverse environments |

|

Although rapid development in counterfactual conditions means that lower-level academic skills such as counting or letter recognition do not make the cut, more advanced levels of literacy and numeracy might. Using data collected by the OECD, Hanushek, Schwerdt, Wiederhold, and Woessmann (2015) show that these more advanced skills are powerful correlates of labor market success, even after adjusting for worker differences in completed schooling, measurement error and the possibility of reciprocal causation between worker skills and the nature of their jobs.

More focused studies have shown that although American children generally acquire rudimentary early mathematics and reading skills, many of them never master more advanced skills (e.g., fractions) that are taught in the later elementary years and used throughout advanced classes in secondary school and higher education (NMAP, 2008; Siegler, Fazio, Bailey, & Zhou, 2013). Moreover, these skills are malleable: intensive interventions have successfully improved children’s fraction knowledge (Fuchs et al., 2013a, 2013b), and additional algebra instruction for children who are at risk for failure in this subject increases children’s subsequent math achievement as well as their likelihood of graduating from high school (Cortes & Goodman, 2014; see Section IV for elaboration). Still, questions remain about the degree to which the factors targeted by these math interventions are fundamental, in and of themselves, for most children’s later academic and labor market success (Bailey, Watts, Littlefield, & Geary, 2014).

As for vocational skills, the community college literature shows payoffs to completing the career-oriented courses such institutions offer, even if this does not lead to a vocational certificate (Belfield and Bailey, 2011). Moreover, rigorous evaluations of some models of vocationally oriented secondary education programs show long-term impacts on earnings; perhaps the most successful is Career Academies, which boosted earnings, post-secondary education and, for men, marriage rates (Kemple and Wilner, 2008).

We see merit in arguments for the trifecta nature of school children’s academic motivation and implicit theories about intelligence and self-concept (Yeager & Walton, 2011). In the case of motivation, the expectancy-value theory of academic motivation holds that children’s cognitive representations of their own academic abilities shape their expectations for success, course choice and, ultimately, the careers they pursue (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). But positive self-appraisals are not enough; children also need to attach intrinsic or instrumental value to their academic pursuits. Interventions targeting some combination of expectations and values are potentially promising ways to boost motivation and promote academic performance. It is also possible that such interventions are achieving their effects via reductions in anxiety and task withdrawal which, in turn, create more opportunities for skill building and learning.

Gaspard et al. (2015) asked students to list arguments for the personal relevance of mathematics to their current and future lives and to write an essay explaining these arguments. Six months after the interventions, students who were randomly assigned this task had higher levels of mathematics motivation (more specifically, they valued mathematics more highly). A similar science-oriented intervention showed positive impacts on high school students’ science grades (Hulleman & Harackiewicz, 2009). Although we lack longer-run evidence on attainment impacts, if motivation can be affected by low-cost writing-based interventions, perhaps such interventions might be used persistently to boost children’s academic motivation throughout their school years.

Implicit theories about intelligence and self-concept concentrate on the importance – and malleability – of a person’s core beliefs and/or construal of the social world (Yeager & Walton, 2011). Students in a New York City public school learned study skills, and a random subset of them also learned about research showing that the brain grows connections and “gets smarter” when a person works on challenging tasks (Blackwell, Trzesniewski, and Dweck, 2007). Students learning only the study skills continued the downward decline in math grades commonly found in middle school, while students learning the incremental theory earned better math grades over the course of the year.

Cohen, Garcia, Purdie-Vaughns, Apfel, and Brzustoski (2009) found a substantial effect on low-performing African American students’ grade point averages two years after an intervention in which the students (as 7th graders) wrote a series of essays in which they affirmed values important to them. The selective effectiveness of the intervention was attributed to the fact that the affected students faced environments that generated stereotype threat (Sherman & Cohen, 2006; Steele, 1988). However, it is notable that several attempts to replicate this intervention in larger samples have shown no consistent impacts (Dee, 2015; Hanselman et al., 2016; Protzko & Aronson, 2016).

Trifecta Skills in Very Adverse Counterfactual Conditions

We began by noting that we would confine most of our discussion to children living in the normative range of environmental conditions found in the modern U.S. However, the potential list of trifecta skills is likely to broaden for children growing up facing extreme forms of poverty and adversity. For example, very poor counterfactual conditions likely led to the long-term treatment effects on intelligence reported in randomized controlled trials in Jamaica and Guatemala, where children received nutritional supplementation (or nutritional supplementation and psychosocial stimulation in the Jamaican study; Maluccio et al., 2009; Walker, Chang, Powell, & Grantham-McGregor, 2005). And very dangerous neighborhood conditions may have been key to the success of the Chicago Crime Lab’s Becoming a Man (BAM) curriculum, which provided youth living in high-poverty neighborhoods on Chicago’s South Side with social-cognitive skill training focused on preventing them from responding to negative events by making hasty decisions, which in their dangerous neighborhoods often results in violence (Heller, Pollack, Ander, and Ludwig, 2013).

Notable Omissions from the Trifecta List

One reason that Table 1’s list of trifecta skills is so short lies in some of the tradeoffs inherent in trifecta conditions. Basic language and literacy skills are clearly fundamental and malleable but do not make the trifecta list because they develop from natural experiences under most counterfactual conditions or are specifically targeted in universally available early formal or informal learning environments. Executive function and rudimentary mathematics skills, both of which develop rapidly in early childhood, do not make our trifecta list for similar reasons.

Another limiting tradeoff for trifecta skills is that some clearly fundamental skills that do not develop under most counterfactual conditions are not likely to be malleable by scalable interventions. This is why we do not include general intelligence or conscientiousness as trifecta skills. And while we do not dispute the malleability of performance on specific executive function tasks, evidence from twin studies of children and adults suggests that individual differences in higher-level factors influencing performance across all executive function components show far less environmental variance (Engelhardt, Briley, Mann, Harden, & Tucker-Drob, 2015; Friedman et al., 2008). This does not mean we will never find a way to change these factors, particularly for children living in especially adverse counterfactual conditions or through interventions that begin very early in life. However, it does imply that those that fall within the existing range of environmental variation may have a limited influence on factors that influence performance on higher-level cognitive skills.

IV. FOOT-IN-THE-DOOR INTERVENTIONS

Developmental timing is crucial for the foot-in-the-door perspective, which holds that building capacities or beliefs at the right time will reduce risk long enough to sustain individuals through periods of high vulnerability (Dodge, Greenberg, Malone, & CPPRG, 2008). Early adolescence is viewed as a particularly productive time for foot-in-the-door interventions, owing to the rapid biological, social and emotional changes that are occurring in a young person’s life, coupled with new opportunities for educational, vocational and social skill development.

Pregnancy prevention is a classic foot-in-the-door intervention example, since it seeks to delay the onset of sexual activity and pregnancy beyond the teen years rather than eliminating these outcomes altogether. Delaying early initiation into substance use is another example, as there is evidence that a delay beyond early adolescence can reduce the long-term risk of substance use and dependence (Dodge et al., 2009; Spoth et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2004).8 Appropriately timed interventions might also equip a child with the right skills or capacities at the right time to seize emerging opportunities (e.g., entry into honors classes). Foot-in-the-door processes are key to the intervention approaches taken in prevention science (Coie et al., 1993).

Foot-in-the-door interventionists may thus leverage sensitive periods of development to alter children’s trajectories. These periods are viewed as windows of opportunity and/or vulnerability, often marked by intense change in individuals and their contexts, as well as in the interactions between individuals and their contexts (Dahl & Spear, 2004; Masten et al., 2004).

The sensitive-period feature of foot-in-the-door processes differs fundamentally from skill-building, which views the intervention task as one of identifying and improving key skills (e.g., grit, executive function, gratification delay, early numeracy) that will persist and generate lifelong benefits. In contrast, foot-in-the-door views the intervention task as one of producing a potentially transitory augmentation of skills or beliefs that will sustain a child or adolescent through a period of risky environments or transitory opportunities to provide a solid foundation for entering the next developmental stage (e.g., from adolescence to adulthood).

On the other hand, both skill-building and foot-in-the-door approaches are embedded in developmental cascades theory. Within this framework, effects of early skills cascade over time to influence later skills via both direct (skill-begets-skill effects, with autoregressive paths through a similar construct over time) and indirect pathways (foot-in-the-door effects, with indirect pathways through more transitory skills). Developmental cascades may be both direct and indirect, as well as unidirectional, bidirectional, and/or reciprocal. A key aspect of the overall cascades approach is that the resulting effects decidedly are not transitory but instead alter the course of development (for a review see Masten & Cicchetti, 2010). Within our framework, skill building and foot-in-the-door pathways represent two related, yet distinct pathways that can lead to sustained intervention effects, both of which could be represented, and simultaneously occur, within a more general developmental cascades model.

Foot-in-the-Door Processes Involving Early Childhood Education Programs

Although early education programs such as Perry and Abecedarian are typically conceived as building a broad and durable set of early skills, it is difficult to distinguish between the mediating roles of subsequent skill-based versus foot-in-the-door processes. The first column of Table 2 shows impacts on special education placement and grade retention based on calculations from the meta-analytic database described earlier. Average effect sizes (as measured by Hedges’ g) from all of the early education programs behind Figure 2 that measured these outcomes are in the .30 sd to .40 sd range, more than enough to lead to subsequent advantages associated with staying on track in mainstream instruction.

Table 2.

Impacts of early childhood education programs on two cascade channels – special education and grade retention

| Meta-analysis | Abecedarian | Perry | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impact | Odds Ratio |

Notes | Impact | Odds Ratio |

Notes | Impact | Odds Ratio |

Notes | |

| Special Education | −0.397** (0.149) | 0.609 | Averaged over 7 studies and 15 effect sizes; 31.4% for control group, 21.8% for treatment group | −0.451** (0.226) | 0.406 (0.412) | Ever received any special education services between grades K-9; 49% for control group, 30% for treatment group | −0.308 (0.202) | 0.587 (0.368) | Ever received any special education services between grades K-12; 50% for control group, 37% for treatment group |

| Retained in Grade | −0.288** (0.074) | 0.625 | Averaged over 16 studies and 34 effect sizes; 34.9% for control group, 25.1% for treatment group | −0.540** (0.223) | 0.373 (0.408) | Ever been retained between grades K-9; 58% for control group, 34% for treatment group | −0.169 (0.261) | 0.706 (0.481) | Ever been retained between grades K-12; 20% for control group, 15% for treatment group |

Notes:

p<.05,

p<.10 in two-tailed tests

Meta-analysis and Abecedarian impacts are calculated by the authors using Hedge’s g. Perry impacts are calculated using Hedge’s g from Table 2 in Barnett, W. S. (1995). Meta-analysis impacts come from McCoy et al. (2015).

If being held back in school or placed in special education leads to negative cascades for some children, perhaps some of the long-term positive outcomes associated with Abecedarian stem from foot-in-the-door processes, rather than being the direct result of skill-based factors such as higher IQ. In the Abecedarian Project, nearly half of the children in the control group were placed in special education; this was true of only 30% of the children who received the Abecedarian preschool treatment – a difference that translated into an effect size (−.45 sd) that was only slightly more negative than that of the meta-analytic average (Table 2). The effect size on special education in the Perry Preschool Project was smaller (−.31 sd) and statistically insignificant, but not far from the meta-analytic average.

In the case of grade retention, Abecedarian treatment and control rates were 34% and 58%, which generated an effect size (−.54 sd) that was almost twice as large as the meta-analytic average (−.29 sd). Perry’s impact on grade retention was statistically insignificant (−.17 sd), but also not far from the meta-analytic average. Thus, Abecedarian’s, but perhaps not Perry’s, long-run impacts may have been sustained in part because of foot-in-the-door advantages in school structures and processes. Perhaps this is because the treatment effect on IQ persisted in Abecedarian. However, in Deming’s (2009) sibling-based analysis of Head Start, grade repetition and learning disability status were affected despite fadeout of effects on children’s cognitive test scores.

Foot-in-the-Door Advantages from Algebra Mastery?

Although algebra mastery may constitute a fundamental skill for the successful performance of some adult jobs, timely mastery of algebra in the early high school years may also provide crucial “foot-in-the-door” advantages for keeping a student on track for a chance at a four-year college education. Most colleges require successful completion of three years of math courses in high school, and the more competitive colleges require four. Algebra and geometry skills are also important for college entrance exams. Efforts to provide “just in time” boosts to algebra skills may yield the right skills at the right time for future success, even if the math skills themselves no longer matter.

Evidence suggesting that appropriately timed and targeted algebra instruction may convey foot-in-the door advantages comes from the Chicago Public Schools’ implementation of a policy that assigned children who performed below a certain level on an 8th grade mathematics exam to take a “double dose” of algebra classes in 9th grade. Using a regression discontinuity design, Cortes and Goodman (2014) estimated that children just below the cutoff who received the extra algebra instruction earned higher grades in 9th grade algebra outperformed controls on a grade-11 mathematics exam, were 12 percentage points more likely to graduate from high school within 5 years, and were 11 percentage points more likely to enroll in college than children just above the cutoff.

It is difficult to evaluate the extent to which foot-in-the-door processes are responsible for Double Dose’s persistent intervention effects. Did the program affect children’s high school graduation rates because children who received the treatment learned a malleable and potentially fundamental skill (algebra), or because a higher likelihood of success in a key class at the beginning of high school set off a positive cascade, leading to more school engagement and, eventually, a higher likelihood of graduation?9 Of course, these are not mutually exclusive hypotheses. However, the treatment effect of the double-dose algebra intervention was larger on students’ 11th grade ACT verbal scores than on their 11th grade ACT math scores, suggesting that algebra knowledge alone was not responsible for the positive effects of the intervention (Cortes & Goodman, 2014).

Light-Touch Interventions Relying on Foot-in-the-Door Processes

Foot-in-the-door effects have several attractive qualities, including their often low implementation cost. For example, an intervention that sent college freshmen information via text messages on how and when to re-file FAFSA applications boosted community college students’ continued enrollment into the spring of their sophomore years by 14 percentage points relative to control-group students who did not receive such messages (Castleman & Page, 2014; similar results have been reported by Bettinger, Long, Oreopoulos, & Sanbonmatsu, 2012, and Owen, 2012). The cost of the intervention averaged about $5 per student served. Information about when and how to fill out FAFSA applications is clearly a peripheral rather than fundamental skill, since it is not useful in other contexts. However, assisting students with their FAFSA applications generated persistent effects on college attendance because it opened the door to college enrollment. Regrettably, no data have been collected on the longer-run impacts of more FAFSA knowledge.

Foot-in-the-door effects might justify efforts to teach children achievement skills that they would probably acquire soon in any event, provided that those gains trigger positive developmental cascades that propel children ahead of their peers in the years that follow. Thus, while teaching children how to count a few months early will not produce a permanent advantage in counting skills, it might allow children to learn simple addition strategies before their peers, which in turn could provide the opportunity for early learning of complex addition strategies and other higher-level math skills. However, as shown in Figure 4, evidence from the Building Blocks experiment does not support the idea that foot-in-the-door processes sustained its pre-K math impacts.

Relying on foot-in-the-door positive cascades is not without risks. Learning a skill makes a child only probabilistically more likely to learn subsequent, more complex, skills in the sequence. And peripheral skills leading to placement in an initially more positive environment do not guarantee that environmental advantages will persist over time. As the probabilities multiply, the estimated effects of an early intervention on later positive outcomes decrease geometrically. This is particularly likely in the case of early interventions. Nonetheless, foot-in-the-door processes may sustain treatment effects if multiple processes are triggered by the intervention. Alternatively, if the probability is close to 100% that the child will learn more advanced skills or enjoy more positive environments if he or she has learned a precursor skill or been placed in a positive environment, foot-in-the-door processes may fully sustain initial impacts.

Study the Doors?

If foot-in-the-door processes support consequential positive or negative developmental cascades, then it becomes important to study the doors themselves to ensure that they promote rather than retard opportunity. Obvious examples of problematic door are when a special-education track traps children into a sequence of inferior educational opportunities, or a school suspension policy increases the chances of involvement with the juvenile and, eventually, adult justice systems.

To the extent that the association between an early intervention and a mediating “door” or the effect of a “door” on subsequent life outcomes varies by time and place, the likely long-term outcomes of short-term interventions may also predictably vary. For example, if some school districts have very effective special education programs, avoiding special education placement would not be considered an important positive intermediate outcome.

Finally, if doors are relative goods (to extend the analogy, if getting in the door requires that someone else exits), interventions may generate negative externalities and will show smaller average positive effects at scale than at the individual level. An example would be entry into a limited number of slots in a gifted or talented program. When interventions enable treated children to benefit from these slots, this means that other children are crowded out of their slots. In these cases, the collective effects of an intervention conducted at scale would add up to less than the sum of its individual effects, and could even be negative (Penner, Domina, Penner, & Conley, 2015).

V. SUSTAINING ENVIRONMENTS

What we call the “sustaining environments” perspective recognizes the importance of building skills and capacities early in life, but views subsequent exogenous environments as crucial for the persistence of the early skill advantages wrought by prior interventions. Ramey and Ramey (2006) draw from their experience with the Abecedarian Project as well as a broader review of the early intervention literature and observe that sustained intervention effects require ongoing post-program educational supports to “maintain children’s positive attitudes and behavior and to encourage continued learning relevant to the children’s lives” (p. 455). They point out that if birth-to-age-five programs are to be deemed successful over the long term, treatment but not control-group children must exhibit rates of development after they enter school that parallel those of more advantaged children. In short, early intervention impacts can be sustained only if they are followed by environments of sufficient quality to sustain normative growth. Enriched post-intervention environments can be consciously planned and implemented, for example by providing high-quality elementary school instruction that complements what has been taught before, or they may arise spontaneously.

Most of these ideas about sustaining environments differ from those in skill-building and foot-in-the-door models, both of which posit that the right kinds of skills and capacities equip children to take better advantage of any environmental opportunity (or in the case of foot-in-the-door, avoid risk) for further skill development. The sustaining environments perspective views early investments as unproductive unless they are accompanied by subsequent investments in sufficiently high-quality schools and other environmental contexts in which development takes place. Proponents of this perspective would not find it surprising that Abecedarian children, who entered desegregated and relatively high-quality Chapel Hill public schools in the 1970s, showed persistently higher IQs than control-group children, while Perry’s children, who entered low-quality and overwhelmingly African-American public schools in Ypsilanti, Michigan did not.10

Sustaining Environments Following Early Childhood Education Programs

Some proponents of early childhood interventions for children from low-income households argue that such programs can launch children on more positive “trajectories.” A pre-K program might succeed in boosting targeted outcomes at the end of pre-K, but what subsequent processes are needed to sustain or even amplify those initial impacts? As illustrated in Figure 4, a key issue is how to design subsequent environments that preserve the math gains seen at the end of the pre-K year.11

One possible but unlikely process is akin to inoculation, with the pre-K program providing some sort of permanent increase in a key skill or capacity that provides a lifetime of benefits. In the case of vaccines, the antibodies generated in response to the vaccine provide continuous protection against infection for years to come. But it is hard to imagine counterparts for the vaccination analogy among the kinds of skills and capacities that we have been discussing. Indeed, it seems unlikely that the often mediocre classrooms and other environments surrounding low-income preschoolers as they move through middle childhood and adolescence will make it possible for gains in the rudimentary skills fostered in pre-K to be translated into sustained gains in more sophisticated skills without some kind of extraordinary environmental enrichment.

Indirect evidence supporting the sustaining environments hypothesis for the Head Start program comes from Currie and Thomas (2000), who find that black Head Start children go on to attend schools of lower quality than other black children, which may have prevented longer-run impacts. More direct but unsupportive evidence on the sustaining environments hypothesis comes from data from the National Head Start Evaluation Study. Jenkins et al. (2015) find no treatment effect interactions for a host of measures of kindergarten and 1st-grade classroom quality. In the case of data from the Building Blocks preschool mathematics intervention, they also fail to find treatment interactions between assignment to Building Blocks and a host of measures of the quality of kindergarten and 1st-grade math instruction. Further, children in the control group with similar levels of achievement as children in the treatment group following the conclusion of the intervention learned more than children in the treatment group in the following year (Bailey et al., 2016). This difference was almost the size of the fadeout effect during this time, which is inconsistent with the hypothesis that relatively high achieving students’ learning is constrained by a low level of instruction they receive following the intervention. All of this evidence suffers from the methodological problem that the post-treatment environments were not randomly assigned.

A stronger design for understanding the effects of sustaining environments on impact persistence is to build sustaining environments into a third treatment condition. In a follow-on treatment condition, Building Blocks randomly assigned kindergarten and 1st-grade teachers in schools that housed the pre-K Building Blocks intervention to receive additional professional development (PD) designed to help bridge the gaps between preschool, kindergarten and first grade. These additional PD sessions brought teachers from all three grades together to discuss what students learn in each grade and to minimize the amount of repeated content. Although this intervention generated somewhat higher math achievement at the end of 1st grade (p<.10), it is not clear that the follow-up moderated the treatment persistence effect, since the design did not assign the K-1 intervention to children who did not participate in Building Blocks during their pre-K year.

Other attempts to build treatment arms involving sustaining environments have not been successful. Half of Abecedarian’s treatment group was randomly assigned at school entry to a 3-year home and school resource program that provided individualized schoolwork assistance to children and help for parents in making home-school connections, plus a learning-oriented camp in each of the three summers. No IQ impacts were observed for the follow-on supplement to Abecedarian’s birth to age-5 intervention, and modest impacts on math achievement at age 8 quickly disappeared. Reading achievement impacts may have been more persistent, but the study was underpowered to detect them.

There are too few experimental studies assessing the impacts of providing subsequent enriching environments to graduates of human capital intervention to warrant firm conclusions. The limited evidence that does exist suggests that (as with the Building Blocks teacher follow-through) it may be important for supplemental enrichment to be geared closely to the activities and goals of the original intervention.

Sustained environments

Generating enriched subsequent environments can also be a conscious goal of the design of an early intervention. For example, prevention research often targets child-parent dyads in hopes of building parenting skills and supporting higher-quality parent-child interactions will persist long after the interventions end (Webster-Stratton and Taylor, 2001). In this case, the program’s joint child-parent skill building is intended to generate immediate improvements in the quality of parent-child interactions, but also to provide exposure to better environments across the course of the child’s development as parents work to monitor the behaviors of their children more closely and play a role in shaping the children’s exposure to more positive home, school and neighborhood environments.12

Indeed, targeting relation-based social and parenting skills to improve children’s social, emotional, academic, and behavioral skills has a long and relatively successful history. A recent review of 46 randomized experimental trials of preventive parenting interventions reported positive effects on a wide range of outcomes from one to twenty years following the intervention (Sandler et al., 2011). Interventions that demonstrated long-run impacts from infancy and early childhood targeted parenting skills, warmth and responsiveness, often in high-risk mothers (e.g., Nurse-Home Partnership; Olds et al., 2007). Long-term impacts have also been documented reliably in multi-component family-level interventions with older children (e.g., Brotman et al., 2008). Unfortunately, despite the long-run impacts of preventive parenting interventions, there is still little evidence to explain the processes that account for these effects over time (Sandler et al, 2015).

Notably, the positive downstream effects related to improved parenting skills are not exogenous to intervention treatment status, and may be better conceptualized in a skill-building framework than in the sustaining environments category described above. In this case, the trained “skill” may exist only in the context of the parent-child dyad, and is thus different than other skills considered in our discussion of skill building. The success of these parenting programs in improving children’s outcomes and leading to long-run positive gains in academic, social and health outcomes leads us to include parenting skills in adverse environments in the bottom panel of Table 1.

Enriched subsequent environments could also be a product of the scale of prior interventions. In the context of early childhood education interventions, the larger the scale at which ECE is offered, the larger the fraction of higher-achieving and better-behaved classmates in K-12 classrooms. This in turn could generate more positive peer effects and allow teachers to push their students through more advanced material, thereby increasing the likelihood of sustaining ECE gains. Some intriguing evidence suggesting that this might be the case comes from a series of articles on elementary school outcomes associated with expenditures on two North Carolina early childhood programs – Smart Start and More at Four (Ladd, Muschkin, & Dodge, 2014; Muschkin, Ladd, & Dodge, 2015; Dodge, Bai, Ladd, & Muschkin, 2015). Both programs rolled out across North Carolina’s counties in the 1990s and early 2000s and produced large variation in county expenditures across time. Dodge et al. (2015) found that spending on both programs boosted test scores and reduced grade retention and special education placements. Most important for our focus on impact persistence, Dodge et al. (2015) found that test score impacts appearing in 3rd grade were sustained through at least 5th grade.

Given the nature of the North Carolina data, it is impossible to distinguish among the direct impact of participating in these preschool programs, the boost to this direct impact from being surrounded by higher achieving and better behaved elementary school peers, and the benefits accruing to “untreated” children. However, taken together, these results suggest that some kinds of peer or instructional processes are at work, which argues against the intervention field’s current practice of concentrating almost exclusively on small-scale evaluation studies.

VI. SOME IMPLICATIONS FOR INTERVENTIONS AND RESEARCH

Bearing in mind the three routes to impact persistence that we have described above but also the limitations arising from the dearth of evidence on longer-run impacts of promising interventions, we outline some of the implications we see for promising intervention approaches. An obvious implication is to ensure that human-capital interventions successfully target what we refer to as “trifecta” skills, behaviors and beliefs – which can be changed, are fundamental for later success, and would not have developed in the absence of the intervention.

The third criterion is much more likely to be met in the case of at-risk as opposed to more advantaged children. But it also generates the most implications for interventions conducted prior to school entry. Indeed, failure to focus on skills that would not otherwise have developed may account for the fadeout patterns observed in many preschool literacy, math and executive function interventions. A key question for ECE intervention design is this: In the absence of any intervention, what preschool literacy, numeracy, executive function, or emotional self-regulation skills do not develop reasonably well over the course of kindergarten and first grade for the population of children who would be targeted by the intervention?

Within the field of prevention science many interventions are focused less on skill building and more on remediation of skills and relationships that may have been damaged due to prolonged exposure to adversity and toxic stress. Shonkoff et al. (2012) describe toxic stress as “strong, frequent, or prolonged activation of the body’s stress response systems in the absence of the buffering protection of a supportive, adult relationship” (p. e236). Exposure to toxic stress is thought to occur among children in abusive or neglectful early environments and is related to a host of adverse changes in the brain that can affect cognitive functioning and mental health.

In the context of our framework, abusive or neglectful environments establish counterfactual conditions that do not lead children to develop normative functioning. Effective interventions targeting these children and/or their environments have the potential to place children back onto a healthy developmental trajectory or buffer the negative effects of the environment, which certainly constitutes building a broader set of fundamental capacities that do not appear in Table 1. It should be noted however that the most effective interventions efforts directed at unusually high-risk populations involve multi-component interventions targeting multiple-levels of the children and their environments (e.g., multi-systemic therapy) rather than just the “skill building” components as defined here. In other words, in the most disadvantaged populations interventions targeting trifecta skills alone are unlikely to generate sustained impacts. Instead, sustaining environments (self-selected or improved via the intervention) will also be required.

From a skill-building perspective, the list of early trifecta skills and behaviors that have reliable long-term impacts may be small indeed, which suggests that focusing on early intervention strategies alone may not be sufficient to promote positive long-run outcomes in children. Instead, developmentally timed interventions, successfully targeting higher-level but far from universally acquired skills across development, may also be required. Examples of potential targets of interventions later in development are listed in the top panel of Table 1 and include vocational skills, an understanding of fractions or algebra, vocabulary or background knowledge that substantially exceeds typical levels. The strategy of focusing on such skills, behaviors or beliefs for disadvantaged children and adolescents is implicit in interventions such as Fast Track, double-dose algebra and intensive tutoring programs aimed at struggling readers. It is also behind interventions that target children’s implicit theories of learning and self-concepts, which are also listed in Table 1. While some of these interventions appear promising, all are in need of much more development, testing (including replication of previous work) and longer-run follow-up.

Disentangling skill-building vs. foot-in-the-door processes requires measuring both in intervention follow-ups. Skill and capacity measurement is commonly done in skill-based intervention follow-ups, although not always for as broad a set of skills and capacities as one might like. Measurement of foot-in-the-door processes such as grade failure or school suspensions is most common in prevention science but needs to be a routine part of follow-ups to all interventions that might operate through foot-in-the-door processes.

Going beyond skill-building, another promising intervention strategy might rely on beneficial peer, classroom and other sustaining environmental effects generated by interventions conducted at scale. It is worrisome that we may be underestimating longer-run impacts from scaled-up ECE intervention because their evaluations are based on small numbers of children scattered across dozens of elementary schools, who are never present in sufficient numbers in any given post-intervention classroom to enable teachers to use more advanced curricula or to generate other kinds of peer benefits to the children themselves and their remaining “untreated” classmates. Understanding peer and classroom dynamics generated by large-scale interventions is clearly an important objective for future research. On the policy side, subsequent peer and classroom dynamics might justify universal preschool interventions targeting non-trifecta academic and socioemotional skills because they would support higher-level instructional content in subsequent grades.

A third intervention approach is to target important but difficult-to-change skills or behaviors with very intensive interventions for subgroups of children most in need of help and least likely to develop those skills in the absence of the intervention. Abecedarian appears to have successfully boosted the IQ levels of children with low initial IQ scores who are living in families with multiple disadvantages. But pulling it off took five years’ worth of year-round full-day center-based services, a highly structured and individualized curriculum focusing specifically on language and literacy, and ongoing monitoring of implementation by university researchers. To our knowledge, however, few interventions within the commonly observed range of intervention intensity that have targeted conscientiousness or its key components (e.g., grit) among children or adolescents have been successfully implemented.

We began by documenting that, on balance, cognitive impacts of early childhood education programs drop quickly after the end of the programs (Figure 2) and suggesting that, more generally, fadeout is a common feature of many early interventions. It is surprising, then, that growing evidence points to beneficial impacts in adulthood of an assortment of interventions ranging from model ECE (Schweinhart et al., 2005; Campbell et al., 2014) and behavior management programs (Dodge et al., 2015) to Head Start (Deming, 2009), a good kindergarten or middle-school teacher (Chetty et al., 2013; Chetty et al., 2010) and the MTO residential mobility program (Chetty, Hendren, & Katz, 2015). How might these long-run impacts have emerged, despite the fadeout of intervention effects on targeted skills?

The answer to this question is unclear, and probably varies across studies. In fact, a case can be made that all three of the processes we describe were at work in the case of Abecedarian and two were at work with Perry. For skill-building, Heckman et al. (2012) argue that conscientiousness was an important mediator of Perry’s long-term effects,13 while Abecedarian showed persistent effects on intelligence test scores (Figure 1), and both Perry and Abecedarian had a persistent positive impact on children’s academic achievement (Campbell et al., 2001; Schweinhart et al., 1993).

In the case of foot-in-the-door, we have already shown that Abecedarian produced large reductions in both special education placement and early grade retention, two important foot-in-the-door processes (Table 2). For sustaining environments, Ramey and Ramey (2006) argue that the resources available to Abecedarian children in desegregated, high-quality classrooms, combined with the early-years treatment to enable many treatment children to “stay on track” across K-12 schooling. And discussions with individuals involved with interviewing Perry families point to the potential importance of persistently higher-quality parental environments produced by Perry’s weekly home visits.14

Allocating credit to each of these three intermediate mechanisms for interventions’ successes is a difficult task. Skill-building predicts persistent effects on children’s skills between the end of treatment and adulthood, but a challenge in testing this hypothesis is identifying the causal effect of a skill on some outcome across development. Foot-in-the-door pathways do not require persistent effects on any skills, but predict that indirect effects of interventions via skills will be large after the intervention, while indirect effects of interventions via contextual factors (e.g., being in the grade predicted by one’s age) will be larger later in development. Testing foot-in-the-door pathways presents the similar challenge of identifying the causal effect of an environment on some outcome across development. These two sets of explanations may be particularly difficult to differentiate, because it is unlikely that all pertinent skills or environments will be measured in any given study.

Sustaining environments hypotheses can be more easily tested in studies in which some treatment is crossed with a later exogenous treatment (e.g., a follow-up treatment) that allows for testing of the interaction between the two exogenous factors. Sustaining environments are present if the sustaining environment interacts positively with the initial treatment. Of course, sustaining environments are not often varied within a given study, and their effects may have to be generalized from studies in which similar potential sustaining environments are exogenous.

In sum, distinguishing among the three processes we highlight can be challenging, particularly in the absence of measures of all of the possible skill and structural pathways, as well as the absence of longer-run information from all but a handful of interventions. Further, it is difficult to imagine that the same set of channels governed the process by which these various interventions generated their adult impacts. Finally, identifying such pathways is a somewhat unique challenge; the most prominent thinkers in the field of causal inference have primarily focused on estimating the effects of known causes (Shadish, 2010), while the mechanism puzzles we have identified require uncovering the unknown causes of known effects. Solving these mechanism puzzles is a particularly important task for future intervention research.