Abstract

Objective:

Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome presents with paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia and is characterized by electrocardiographic (ECG) findings of a short PR interval and a delta wave. The objective of this study was to evaluate the electrophysiological properties of children with WPW syndrome and to develop an algorithm for the management of these patients with limited access to electrophysiological study.

Methods:

A retrospective review of all pediatric patients who underwent electrophysiological evaluation for WPW syndrome was performed.

Results:

One hundred nine patients underwent electrophysiological evaluation at a single tertiary center between 1997 and 2011. The median age of the patients was 11 years (0.1-18). Of the 109 patients, 82 presented with tachycardia (median age 11 (0.1-18) years), and 14 presented with syncope (median age 12 (6-16) years); 13 were asymptomatic (median age 10 (2-13) years). Induced AF degenerated to ventricular fibrillation (VF) in 2 patients. Of the 2 patients with VF, 1 was asymptomatic and the other had syncope; the accessory pathway effective refractory period was ≤180 ms in both. An intracardiac electrophysiological study was performed in 92 patients, and ablation was not attempted for risk of atrioventricular block in 8 (8.6%). The success and recurrence rate of ablation were 90.5% and 23.8% respectively.

Conclusion:

The induction of VF in 2 of 109 patients in our study suggests that the prognosis of WPW in children is not as benign as once thought. All patients with a WPW pattern on the ECG should be assessed electrophysiologically and risk-stratified. Ablation of patients with risk factors can prevent sudden death in this population.

Keywords: accessory pathway, ablation, children, Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome, ventricular fibrillation

Introduction

Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome may present with paroxysmal tachycardia and is characterized by the electrocardiographic finding of a short PR interval and a delta wave. Rarely, sudden death that is caused by the rapid conduction of atrial fibrillation (AF) over the accessory pathway resulting in ventricular fibrillation (VF) may be the first manifestation of WPW syndrome (1-3). Although controversy regarding the incidence of sudden death exists, the risk is thought to be 3%-4% over a lifetime in symptomatic patients (4), and ablation of the accessory pathways is thought to prevent this risk. The objective of this study was to evaluate the electrophysiological properties of children with WPW syndrome and to develop an algorithm for the management of these patients with limited access to electrophysiological study.

Methods

A review of patient charts and electrophysiological data of patients aged ≤18 years that underwent electrophysiological assessment for WPW ECG pattern at Hacettepe University pediatric cardiology clinic was performed in this retrospective descriptive study.

A review of patient charts and electrophysiological data of patients aged ≤18 years that underwent electrophysiological assessment for WPW ECG pattern at Hacettepe University pediatric cardiology clinic was performed in this retrospective descriptive study. The study was approved by the institutional Ethic Committee.

All clinical and EPS data were reviewed. Clinical data included patient age, gender, weight, and clinical manifestations, including supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) and syncope; EPS data included the site and number of accessory pathways (APs) when possible, the presence or absence of induced atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia (AVRT), the presence or absence of atrial fibrillation (AF), and the accessory pathway effective refractory period (APERP), defined as the longest coupling interval at which anterograde block in the bypass tract was observed.

Electrophysiological study

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents prior to the procedure. In patients aged less than 5 years or who weighed less than 20 kilograms, an electrophysiological study was performed by the transesophageal route. All patients accepted transesophageal study which was performed successfully without any complications. Transesophageal electrophysiological study (TEEPS) was performed under conscious sedation with a 6-F quadripolar electrode (Esokid 4, Fiab SpA, Florence, Italy) inserted through the nares into the esophageal level, at which optimum atrial signals were obtained. Atrial stimulation was done with a programmable stimulator (Fiab Programmable Cardiac Stimulator 8.817) with a pulse width and amplitude capacity between 5 ms and 20 ms and 5 mA and 45 mA, respectively. Programmed atrial stimulation at a drive cycle length of 400 ms was performed, and the APERP was recorded. Single and pair extrastimuli, incremental pacing, and burst pacing were performed to induce AVRT or AF. If sustained tachycardia was not induced under basal conditions, the pacing protocol was repeated after isoproterenol (0.05-0.1 μg/kg/min) infusion. Induced tachycardia was terminated by atrial overdrive pacing. Accessory pathway location was established by the use of the ECG criteria according to Boersma's algorithm (5).

Intracardiac electrophysiological study (IEPS) was performed to all patients aged more than 5 years or who weighed more than 20 kilograms. The study was performed under local anesthesia in cooperative patients; the remaining patients were sedated by repeated administration of midazolam (0.1 mg/kg) and ketamine (1-2 mg/kg). An electrophysiological study using standard techniques and pacing protocols was performed in all patients. A manifest pathway was localized by the shortest atrioventricular (AV) interval and earliest ventricular activation in sinus rhythm, as well as the shortest ventriculo-atrial (VA) time and earliest atrial activation during tachycardia. Multiple APs were defined as 2 or more distinct sites of early anterograde and/or retrograde activation. Surface and endocardial ECG potentials were recorded and stored on a multichannel recorder (CardioTek, EP-TRACER, THE Maastricht EP system, Maastricht, the Netherlands). Atrial and ventricular incremental pacing up to the minimal cycle length, maintaining atrioventricular or ventriculo-atrial 1:1 conduction, and programmed atrial and ventricular stimulation were performed. Ablation was performed in all patients with inducible tachycardia or an APERP <250 ms that underwent IEPS, except in those with a pathway location in close proximity to the AV node. After the electrophysiological evaluation was performed, a 7-F deflectable electrode catheter was induced by the femoral vein for ablation of a right-sided AP or through the femoral artery for ablation of a left-sided AP; in patients with a patent foramen ovale, the left atrium was accessed through the defect. Radiofrequency (RF) energy was delivered at a power of 30 to 50 W, and if conduction over the accessory pathway disappeared within 10 seconds, the energy was maintained for 60 to 120 seconds with a maximal temperature of 65°C. If conduction persisted for 10 seconds, energy was stopped, and further mapping was done at a different site.

Follow-up

After the procedure, patients were monitored overnight; all patients had a physical exam and a control ECG before discharge. Patients were assessed at 1, 6, and 12 months and annually after 12 months with a complete history, physical examination, and ECG. Patients aged ≤1 year had a control TEEPS performed when they were 1 year old after cessation of antiarrhythmic therapy. Patients with recurrence of the AP that had RF ablation underwent a second ablation procedure.

Results

Between January 1997 and January 2011, 109 patients with WPW were identified. All met the inclusion criteria of the study, and none was excluded. Of them, 66 (60%) were male. The median age and weight of the patients were 11 years (0.1-18) and 36 kilograms (3-93), respectively. Of the 109 patients, 4 were in the infancy period; of these 4 patients, 2 had a history of fetal tachycardia, and 2 presented with heart failure. Both patients with fetal tachycardia underwent TEEPS in the postnatal period and were started on antiarrhythmic therapy, because SVT was induced with TEEPS.

Seventeen patients (15.5%) underwent electrophysiological evaluation with TEEPS only. In our institution, patients are first risk-stratified with TEEPS, and those with high risk are prioritized in the waiting list for ablation; also, patients aged <5 years or <20 kilograms are evaluated with TEEPS only; they are reevaluated when they reach the appropriate age or weight and proceeded with ablation. Of the 17 patients, 11 had inducible tachycardia. The APERP of the patients with inducible tachycardia was <250 milliseconds (ms), while it was >250 ms in all of the patients without inducible tachycardia. Six patients without inducible tachycardia and an APERP>250 ms were evaluated as low-risk and are still followed at the outpatient clinic without antiarrhythmic therapy. Ablation is planned in the remaining patients.

Of the 109 patients included in the study, the initial symptom was tachycardia in 82 and syncope in 14 patients, and 13 patients were asymptomatic. The median age of patients presenting with tachycardia was 11 (0.1-18) years. Thirteen of the tachycardia patients underwent only a transesophageal electrophysiological study; 8 of these patients did not undergo ablation, because their weight was <20 kg; and 5 had an ablation planned after the study period. Of the 82 tachycardia patients, atrial fibrillation (AF) was induced in 6 patients (7.3%); the APERP was <250 ms in all and <220 ms in 3 of these 6 patients. All of the patients with inducible AF underwent ablation.

Of the 109 patients, 14 patients presented with syncope. The median age of the patients with the presenting symptom of syncope was 12 (8-16) years. Atrial fibrillation was induced in 5 of the 14 patients (36%), and AF degenerated to ventricular fibrillation (VF) in 1. The APERP of the patients with syncope was 270 ms in 1, <250 ms in 6, and <220 ms in 7 patients. The APERP value was <220 ms in 4 and <250 ms in 1 of the patients with inducible AF. The APERP value of the patient with VF was recorded as 180 ms.

Thirteen of the patients included in the study were asymptomatic. The median age of asymptomatic patients was 10 (2-13) years. Tachycardia was induced in 7 patients during EPS, AF was induced in 1 patient, and AF degenerated to VF in that patient, both during TEEPS and IEPS. The APERP value of the asymptomatic patient with inducible AF and VF was <180 ms, and the APERP value of all patients with inducible tachycardia and 3 of the patients without inducible tachycardia was <250 ms. Ablation was performed in 6 of the patients with inducible tachycardia. Since the other patient with inducible tachycardia was 2 years old, antiarrhythmic therapy was started, and the patient was followed at the outpatient clinic without symptoms during the study period. In 3 of the 6 asymptomatic patients without inducible tachycardia, ablation was performed, since the APERP was <250 ms and the pathways were thought to be risky. Atrial fibrillation that degenerated to VF was found to be 7.7% (1/13) in the asymptomatic patient group in our study. Overall, the percentage of VF in the study group was found to be 1.8% (2/109).

The accessory pathway localization was posteroseptal in 26 (23.8%), anteroseptal in 25 (22.9%), midseptal in 3 (2.8%), left free side in 28 (25.7%), right free side in 12 (11%), multiple in 8 (7.4%), and undetermined in 7 (6.4%). Intracardiac EPS was done in 92 patients, and ablation was not attempted in 8 (8.6%), since the AP had a parahissian location and ablation had a high risk of AV block. Ablation was performed in 84 patients; acute success was achieved in 72 (85.7%). Ablation was unsuccessful in 8 (9.5%) patients. Ablation was accepted to be partially successful in 4 (4.8%) patients, in whom the AP potential persisted, but tachycardia could not be induced despite isoproterenol infusion. Together with the partially successful patients, the acute success rate was 90.5%. The recurrence rate was 23.8%.

Discussion

A WPW ECG pattern is found in 0.15% to 0.25% of the population, and one-third of these people are thought to develop arrhythmias during a 10-year follow-up (4, 6-8). Diagnostic evaluation and treatment protocols have been well defined in symptomatic adult patients with WPW syndrome, whereas the management of asymptomatic patients, especially in the pediatric age group, is still very controversial.

Of the 109 patients included in the study, 4 were in the infancy period; 2 of them had fetal tachycardia, and 2 had heart failure upon admission. Diagnosing SVT during the infancy period might be difficult; patients present with nonspecific symptoms, such as tachypnea, difficulty in feeding, irritability, and findings of heart failure if tachycardia continues for a long time. In a study by Gilljam et al. (9), 109 patients diagnosed with SVT in the neonatal period were analyzed; they reported that 52 of the patients presented with heart failure, 10 presented with hydrops fetalis, and 9 presented with fetal tachycardia. The high rate of patients with heart failure indicates the difficulty in diagnosing an SVT in infants before symptoms of heart failure develop. Two of our patients had fetal tachycardia, and they were evaluated with TEEPS in the postnatal period and were started on antiarrhythmic therapy, because SVT was induced during TEEPS. Starting antiarrhythmic therapy with an indication of inducible SVT during TEEPS might have prevented these patients from developing SVT-related heart failure.

The most worrisome symptom of WPW is syncope and sudden death. The mechanism of sudden death in patients with WPW syndrome is very rapid conduction of atrial flutter and AF over the accessory pathway, which provokes VF. The lifetime incidence of sudden death is estimated to be about 3% to 4% (4, 10). Especially in the pediatric population, VF and sudden death can be the first arrhythmic event (1-3).

Santinelli et al. (11) reported their findings in 184 asymptomatic children; patients underwent an EP study at the start of the study, and they were followed every 6 months with an ECG and 24-h Holter monitoring with the primary endpoint of the first arrhythmic event. Over a median follow-up of 57 months, 51 children became symptomatic; 19 patients had potentially life-threatening arrhythmias with a rapid ventricular response. The most striking finding of the study was the fact that some children with potentially life-threatening arrhythmias had minimal or atypical symptoms, such as nausea, sudden tiredness with anxiety, abdominal pain and swelling, and inability to concentrate while playing. Furthermore, 3 of the 19 patients with potentially life-threatening arrhythmias had documented VF that required cardiovascular resuscitation. These findings indicated that the natural history of asymptomatic children with a WPW ECG pattern may not be as benign as previously thought, since the onset of potentially life-threatening arrhythmias may be unsuspected in many cases. Our study group had 2 patients that developed VF during EP study. One of our patients had syncope as the first symptom, and the other was asymptomatic. The induction of VF in the EP study in 2 of our patients also indicates that WPW might have serious clinical implications in children and that all patients who are diagnosed with WPW should undergo risk stratification, regardless of symptoms.

Different studies have yielded variable incidences of life-threatening arrhythmias leading to sudden death in WPW; however, the risk seems to be much higher in pediatric patients than in adults. In a study of 75 asymptomatic patients, Leich et al. (12) did not document any sudden death in a median of 4.3 years of follow-up. In a population study by Munger et al. (4), 113 patients were followed for a median of 12 years; 30% of the asymptomatic patients developed symptoms, and 2 previously symptomatic patients died suddenly. Another long-term observational study was conducted by Fitzsimmons et al. (13), in which they followed 228 military aviators for a median of 21.8 years; 15.3% of the asymptomatic patients developed SVT, and 1 patient was lost to sudden cardiac death. Lower incidences of sudden death have been reported in different studies; however, the incidence of symptoms seems to increase with longer follow-up time and a younger population sample (8, 14, 15).

In 1979, Klein et al. (2) reported on 25 patients that presented with VF; 3 of the patients were children, aged 8, 9, and 16 years, and all were previously asymptomatic. Bromberg et al. (16) reported that from a group of 60 children undergoing WPW surgery, 10 children had clinical cardiac arrest, and only 1 of these 10 children had a prior history of syncope or atrial fibrillation. In 1990, Silka et al. (17) published a study in which they analyzed the outcome of 15 consecutive patients who were resuscitated from pulseless ventricular tachycardia or VF; one-fifth of the children with aborted sudden death were later diagnosed with WPW. In recent years, prospective studies from Italy reported the clinical and electrophysiological findings of asymptomatic patients (10, 11, 18, 19). A total of 10 previously asymptomatic patients developed VF; 8 were resuscitated and 2 patients had died. Five of 10 patients with VF and 1 patient with sudden death were pediatric patients. The data from these studies suggest that the incidence of sudden death is higher in the pediatric population, since most of the patients with potentially life threatening accessory pathways become symptomatic or die before they reach adulthood.

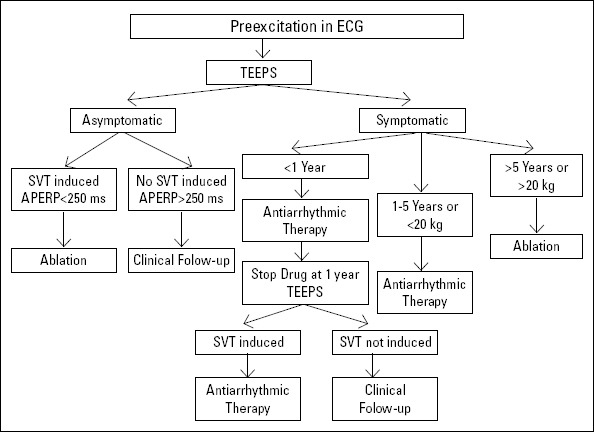

When the clinical and electrophysiological characteristics of patients with documented VF are evaluated, the factors associated with life-threatening symptoms are: clinical or electrophysiological induced atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response (2, 20), documented SVT (2), prior syncope (3), the presence of multiple accessory pathways (2, 10, 11), APERP <270 ms (2, 21, 22), and young age (<30 years) (10, 11, 18, 19). The measurement of the shortest pre-excited RR interval (SPERRI) during AF is thought to be a more sensitive and accurate risk factor; SPERRI values of 220-50 ms and especially less than 220 ms are more commonly seen in patients with aborted sudden cardiac death (11, 16). SPERRI was not measured in our patients; however, the APERP of both patients with induced VF was ≤180 ms. Recently, an expert consensus statement was published regarding risk stratification for patients aged 8-21 years with asymptomatic WPW ECG patterns (23). The expert consensus statement suggests that all children with asymptomatic persistent manifest pre-excitation undergo exercise stress test and that all patients other than those with intermittent preexcitation or an abrupt and clear loss of pre-excitation during the exercise stress test undergo an electrophysiological study. The consensus proposes ablation as a Class IIA indication in patients with SPERRI ≤250 ms and as a Class IIB indication in patients with inducible SVT. For patients with SPERRI >250 ms and the absence of inducible SVT, deferring ablation is a Class IIA indication; however, if the pathway location does not increase the risk of adverse events, ablation might be considered a Class IIB indication. If patients who are considered to be low-risk through risk stratification develop symptoms during follow-up, they may be considered to be eligible for catheter ablation procedures, regardless of prior assessment. The statement also suggests using the shortest pre-excited RR interval, determined by rapid atrial pacing, as a reasonable surrogate to SPERRI. Although this statement makes suggestions on the management of asymptomatic patients beyond 8 years, for patients aged less than 8 years, no consensus regarding risk stratification and management exists. In light of the lack of guidelines in the very young, every center should develop its own protocol. The assessment that is performed and the management algorithm that was developed in our center in light of our findings of the current study are given in Figure 1. Current pediatric guideline suggests performing an exercise test as stated above for children older than 8 years; however, up to 20% of patients at risk for sudden death might be missed with exercise test (24). Combined with the technical difficulties in performing exercise test in the pediatric population, the difficulties of identifying an abrupt loss of pre-excitation and the risk of missing 20% of patients at risk for sudden death, we did not include exercise test in our risk stratifying process and designed an algorithm that uses TEEPS instead. We think that TEEPS is a reasonable alternative for patients that can not undergo IEPS because of possible catheterization-related complications. Also, for centers that do not perform ablation or have a long waiting list, TEEPS can be a lifesaving method in identifying those with the highest risk. We think that in asymptomatic patients in whom AF can not be induced and the SPERRI value can be measured, an APERP value <250 ms can be used as a risk factor, and ablation may be performed.

Figure 1.

Management algorithm for patients diagnosed with WPW

AERP - anterograde effective refractory period; SVT - supraventricular tachycardia; TEEPS - transesophageal electrophysiological study

The presenting symptom was tachycardia in 82 and syncope in 14 of our patients; 13 patients were asymptomatic. When the inducibility of AF according to the symptoms was evaluated, AF was induced in 6 (6/82, 7.3%) of the tachycardia patients, 5 (5/14, 36%) of the syncope patients, and 1 (1/13, 7.7%) of the asymptomatic patients. A striking finding of our study was the degeneration of AF to VF in 2 of these patients; the incidence of VF was found to be 1.8% in our study, and the APERP of both of these patients was ≤180 ms.

The success rate of RFA in pediatric patients with WPW varies by arrhythmia substrate location and operator experience. In the early era, the Pediatric Radiofrequency Ablation Registry reported a success rate of 91% in the ablation of accessory pathways (25). To evaluate the effect of operator experience, Kugler et al. (26) divided the registry data into an early and later era. Overall, a significant increase from 91% to 95.2% in the success rate could be observed in the later era. Our study includes the learning period of ablation; therefore, the combined acute success rate of 90.5% is in concordance with the studies mentioned above. The recurrence rate in the early era was 23%; however, in a more recent report of the Registry, the recurrence rate at the 1-year follow-up was reported to be 10.7%. When the recent registry data were evaluated for pathway location, recurrence was observed in 24.2%, 15.8%, and 59.3% for the right septal, right free wall, and left free wall accessory pathways. The recurrence rate of 28.5% in our study is similar to the rate reported for right septal pathways in the recent Registry report.

Study limitations

This study is limited by the inherent nature of a retrospective study and the limited number of asymptomatic patients. Atrial fibrillation could not be induced in the majority of our patients, most possibly due to lack of aggressiveness during the electrophysiological study. Another important limitation of the study was non-documentation of the SPERRI values of patients with induced AF. Despite these limitations, the finding of VF in 2 of our patients and documentation of an APERP of ≤180 ms in both patients are significant.

Conclusion

Induced AF with rapid ventricular response degenerating to VF in 2 patients indicates a VF incidence of 1.8% in our study group, placing them at an increased risk for sudden cardiac death. All patients with a finding of a WPW ECG pattern should be evaluated electrophysiologically for risk stratification, regardless of symptoms. Identifying patients whose accessory pathway characteristics could be associated with increased risk of VF and ablation of these pathways can prevent possible sudden cardiac deaths.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Authorship contributions: Concept - Sema.Ö., S.Ö.; Design - A.Ç.; Supervision - Sema.Ö., S.Ö.; Resource - D.A.; Materials - D.A.; Data collection and/or processing - M.Ş., I.Y.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - T.K., A.Ç.; Literature search - M.Ş., I.Y.; Writing - I.Y.; Critical review - T.K., I.Y.

References

- 1.Timmermans C, Smeets JL, Rodriguez LM, Vrouchos G, van den Dool A, Wellens HJ. Aborted sudden death in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76:492–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80136-2. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein GJ, Bashore TM, Sellers TD, Pritchett EL, Smith WM, Gallagher JJ. Ventricular fibrillation in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1979;301:1080–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197911153012003. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montoya PT, Brugada P, Smeets J, Talajic M, Della Bella P, Lezaun R, et al. Ventricular fibrillation in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Eur Heart J. 1991;12:144–50. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a059860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munger TM, Packer DL, Hammill SC, Feldman BJ, Bailey KR, Ballard DJ, et al. A population study of the natural history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in Olmsted County, Minnesota, , 1953-1989. Circulation. 1993;87:866–73. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.3.866. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boersma L, Garcia-Moran E, Mont L, Brugada J. Accessory pathway localization by QRS polarity in children with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2002;13:1222–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2002.01222.x. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith RF. The Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome as an Aviation Risk. Circulation. 1964;29:672–9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung KY, Walsh TJ, Massie E. Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome. Am Heart J. 1965;69:116–33. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(65)90224-3. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krahn AD, Manfreda J, Tate RB, Mathewson FA, Cuddy TE. The natural history of electrocardiographic preexcitation in men. The Manitoba Follow-up Study. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:456–60. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-6-456. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilljam T, Jaeggi E, Gow RM. Neonatal supraventricular tachycardia: outcomes over a 27-year period at a single institution. Acta Paediatr. 2008;97:1035–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00823.x. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pappone C, Manguso F, Santinelli R, Vicedomini G, Sala S, Paglino G, et al. Radiofrequency ablation in children with asymptomatic Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1197–205. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040625. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santinelli V, Radinovic A, Manguso F, Vicedomini G, Gulletta S, Paglino G, et al. The natural history of asymptomatic ventricular preexcitation a long-term prospective follow-up study of 184 asymptomatic children. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:275–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.037. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leitch JW, Klein GJ, Yee R, Murdock C. Prognostic value of electro-physiology testing in asymptomatic patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White pattern. Circulation. 1990;82:1718–23. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.5.1718. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzsimmons PJ, McWhirter PD, Peterson DW, Kruyer WB. The natural history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in 228 military aviators: a long-term follow-up of 22 years. Am Heart J. 2001;142:530–6. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.117779. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berkman NL, Lamb LE. The Wolff-Parkinson-White electrocardiogram. A follow-up study of five to twenty-eight years. N Engl J Med. 1968;278:492–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196802292780906. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goudevenos JA, Katsouras CS, Graekas G, Argiri O, Giogiakas V, Sideris DA. Ventricular pre-excitation in the general population: a study on the mode of presentation and clinical course. Heart. 2000;83:29–34. doi: 10.1136/heart.83.1.29. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bromberg BI, Lindsay BD, Cain ME, Cox JL. Impact of clinical history and electrophysiologic characterization of accessory pathways on management strategies to reduce sudden death among children with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:690–5. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00519-6. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silka MJ, Kron J, Walance CG, Cutler JE, McAnulty JH. Assessment and follow-up of pediatric survivors of sudden cardiac death. Circulation. 1990;82:341–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.2.341. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pappone C, Santinelli V, Manguso F, Augello G, Santinelli O, Vicedomini G, et al. A randomized study of prophylactic catheter ablation in asymptomatic patients with the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1803–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035345. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pappone C, Santinelli V, Rosanio S, Vicedomini G, Nardi S, Pappone A, et al. Usefulness of invasive electrophysiologic testing to stratify the risk of arrhythmic events in asymptomatic patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White pattern: results from a large prospective long-term follow-up study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:239–44. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02706-7. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morady F, Sledge C, Shen E, Sung RJ, Gonzales R, Scheinman MM. Electrophysiologic testing in the management of patients with the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome and atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 1983;51:1623–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(83)90198-4. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dubin AM, Collins KK, Chiesa N, Hanisch D, Van Hare GF. Use of electrophysiologic testing to assess risk in children with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Cardiol Young. 2002;12:248–52. doi: 10.1017/s1047951102000549. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell RM, Strieper MJ, Frias PA, Collins KK, Van Hare GF, Dubin AM. Survey of current practice of pediatric electrophysiologists for asymptomatic Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Pediatrics. 2003;111:e245–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.e245. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen MI, Triedman JK, Cannon BC, Davis AM, Drago F, Janousek J, et al. PACES/HRS expert consensus statement on the management of the asymptomatic young patient with a Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW, ventricular preexcitation) electrocardiographic pattern: developed in partnership between the Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES) and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS). Endorsed by the governing bodies of PACES, HRS, the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF), the American Heart Association (AHA), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS) Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:1006–24. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.03.050. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Novella J, DeBiasi RM, Coplan NL, Suri R, Keller S. Noninvasive risk stratification for sudden death in asymptomatic patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2014;15:283–9. doi: 10.3909/ricm0717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kugler JD, Danford DA, Houston K, Felix G. Radiofrequency catheter ablation for paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia in children and adolescents without structural heart disease. Pediatric EP Society, Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation Registry. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:1438–43. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00736-4. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kugler JD, Danford DA, Houston KA, Felix G. Pediatric radiofrequency catheter ablation registry success, fluoroscopy time, and complication rate for supraventricular tachycardia: comparison of early and recent eras. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2002;13:336–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2002.00336.x. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]