Abstract

Epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) is a component of the visceral adiposity located between the heart and pericardium. It is associated with certain diseases, such as metabolic syndrome, coronary artery disease, and hypertension. Therefore, measurement of EAT thickness has recently gained importance. Examination by transthoracic echocardiography for measuring EAT thickness is preferable because of easy availability and low cost. The present review focuses on the method of measuring EAT thickness by transthoracic echocardiography as well as the issues of concern.

Keywords: epicardial adipose tissue, epicardial fat, echocardiography

Introduction

Epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) is part of visceral adipose tissue localized between the heart and pericardium, particularly in the atrioventricular and interventricular sulcus, lateral wall of the right ventricle, and around the coronary arteries (1-3). EAT has endocrine, paracrine, vasocrine, and inflammatory characteristics (4-6) and is associated with metabolic syndrome (7), insulin resistance (8), coronary artery disease (9, 10), and hypertension (11, 12). Therefore, measurement of EAT thickness has gained importance. EAT thickness can be measured by transthoracic echocardiography, cardiac computed tomography (CT), and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) methods. Evaluation by transthoracic echocardiography has come to the forefront because of many advantages, such as easy availability, low cost, no radiation exposure, fastness, and reproducibility. Measurement of EAT thickness by transthoracic echocardiography is discussed in this article.

EAT measurement by echocardiography was first defined in 2003 by Iacobellis et al. (13). They expressed EAT as an echofree space above the right ventricular free wall by transthoracic echocardiography and measured the thickness from the anterior aspect of the right ventricular free wall through parasternal long and short axis windows (13). They stated that the reason for them to prefer this point was the highest EAT thickness in that area and optimal cursor beam orientation in each view (13). By this method, they determined that EAT measurements are correlated with MRI measurements and confirmed the accuracy of measurements by echocardiography (13). Further studies began to measure EAT thickness considering this method, which was recommended by Iacobellis et al. (13), as the reference.

How is the epicardial adipose tissue measured and from where?

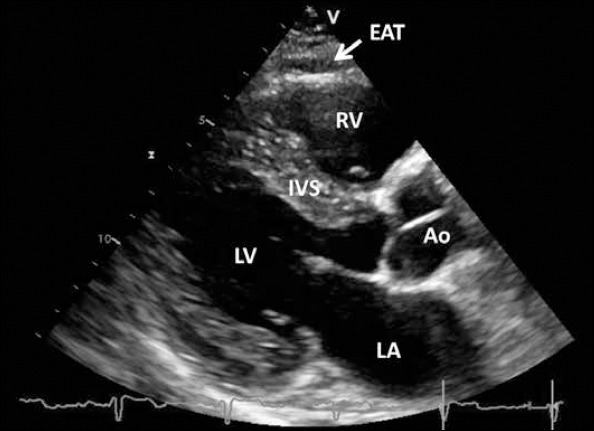

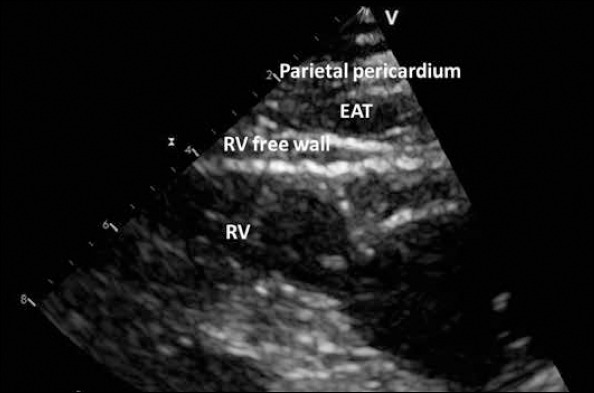

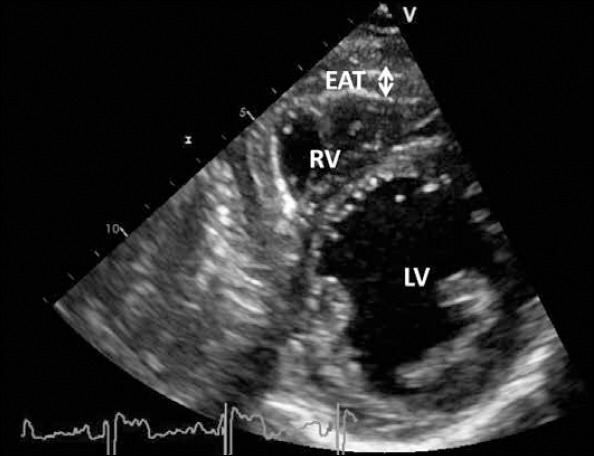

EAT demonstrated by transthoracic echocardiography is the echo-lucent area between the epicardium of the right ventricle and parietal pericardium, which is seen as a thick line above the right ventricular free wall on echo (Fig. 1, 2) (7, 9).

Figure 1.

Transthoracic echocardiographic view of epicardial adipose tissue. Epicardial adipose tissue is an echo-lucent area between epicardial surface and parietal pericardium in front of the right ventricular free wall and is pointed by a white arrow Ao- aorta; EAT- epicardial adipose tissue; IVS- interventricular septum; LA- left atrium; LVleft ventricle; RV- right ventricle

Figure 2.

The view of epicardial adipose tissue(zoomed in). Epicardial adipose tissue is an echo-lucent area between the epicardium of the right ventricle and parietal pericardium in front of the right ventricular free wall EAT- epicardial adipose tissue; RV- right ventricle

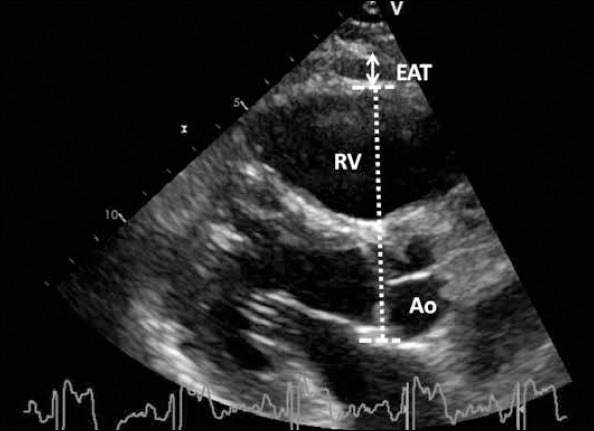

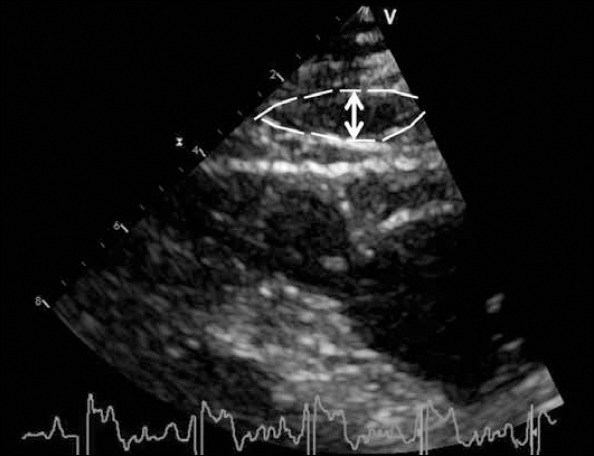

For EAT measurement, the individual is placed in the left lateral decubitus position, and an optimal parasternal long-axis view is tried to be obtained through the left sternal 2-3 intercostal space. Interventricular septum and particularly the aortic root are considered as the reference points for the measurement from the parasternal long-axis view. Taking the aortic root as the reference, measurement is made by putting the right ventricular free wall and the aortic annulus in the midline of ultrasound waves (Fig. 3) (14-18). The hypoechoic area extending from epicardial surface to the parietal pericardium in front of the right ventricular free wall is vertically measured at the thickest level (Fig. 3). More sensitive measurements can be made by enhancing depth setting and magnifying the view to assess EAT thickness more clearly (Fig. 4) (9). Some references recommend the measurements to be made in three (3, 15, 17, 18), some references recommend to be made in six (9), and some references recommend to be made in 10 (3) cardiac cycles. Making the measurements in at least three cardiac cycles, calculating the mean value, and not being satisfied with a single measurement would be convenient for accurate measurement.

Figure 3.

Making measurement by taking the aortic root as the reference and placing in the midline between the right ventricular free wall and aortic annulus. Vertical length between the right ventricular free wall and parietal pericardium is measured. The area between the white arrows indicates epicardial adipose tissue thickness Ao- aorta; EAT- epicardial adipose tissue; RV- right ventricle

Figure 4.

The borders of epicardial adipose tissue in magnified size and measurement of epicardial adipose tissue. White arrow points out the measurement of epicardial adipose tissue thickness

After measuring from the parasternal long-axis, the probe is switched to 90° clockwise and parasternal short-axis view is obtained. In the parasternal short-axis view, mid-chordal region (19), the tip of the papillary muscles (18, 19), and interventricular septum (19) can be regarded as reference points (19). In general, measurement from 2 cm away from the interventricular septum (14, 16) and from the parasternal short-axis mid-ventricular level is recommended (20). EAT is measured from the echo-lucent area between the right ventricle and parietal pericardium on the parasternal short axis section as shown in Figure 5 (3). Parasternal long- and short-axis measurements must be averaged to obtain the mean thickness.

Figure 5.

Measurement of epicardial adipose tissue thickness from parasternal short axis view. Epicardial adipose tissue thickness is marked by white two-sided arrow EAT - epicardial adipose tissue; LV - left ventricle; RV - right ventricle

In the initial publications, although EAT was most frequently measured during end-systole due to deformation and pressure on EAT in the distal aspect (13, 14), it is measured, in some publications during end-diastole in order to be consistent with cardiac CT and MRI (9, 15, 19). In our studies, we prefer measuring EAT thickness during diastole (10, 11, 16). Performing EAT measurement during end-diastole just before the R-wave on the ECG would be convenient for the standardization of publications and measurements (3). It should be kept in mind that end-systolic measurements will reveal higher values as compared with end-diastolic measurements. Therefore, it is necessary to pay attention whether measurements have been made during end-systole or -diastole while interpreting EAT thickness in the publications.

How can we differentiate epicardial adipose tissue from pericardial adipose tissue?

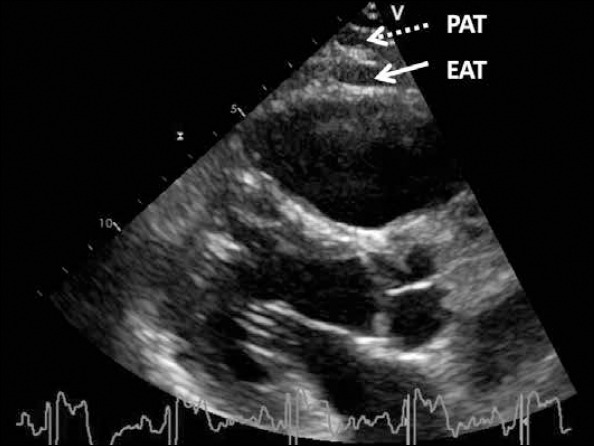

One of the important issues to pay attention while measuring EAT thickness is to make a clear differentiation between pericardial adipose tissue and EAT. Pericardial adipose tisse and EAT arise from different embryonic origins; their local circulation and biomolecular features are different (21). EAT should be differentiated from pericardial adipose tissue because it is a real visceral adipose tissue (21).

Pericardial adipose tissue is the hypoechoic area in front of EAT and parietal pericardium (Fig. 6) (19). Although different from EAT, it does not alter with cardiac cycle (19, 21). It can be easily differentiated from EAT with these features.

Figure 6.

Differentiation between epicardial adipose tissue and pericardial adipose tissue. Epicardial adipose tissue is pointed out by white arrow, and pericardial adipose tissue is pointed out by dashed- line arrow EAT - epicardial adipose tissue; PAT- pericardial adipose tissue

Differentiation between epicardial adipose tissue and pericardial effusion

Differentiating EAT from pericardial effusion is of great importance. Even though the EAT is viewed as a hypoechoic area, it has different features from pericardial effusion. EAT has specific echo-density that comprises echo-lucent areas and whitish-speckled appearance (16). However, pericardial effusion has more hypoechoic appearance. In addition, although EAT is limited to the front of the right ventricle, pericardial effusion reveals wider spread, and usually it is more prominent in the posterolateral aspect of the left ventricle while the patient is left lateral decubitis position.

What is the normal value of epicardial adipose tissue thickness?

There is yet no definite value considered normal for EAT thickness. There are inconsistencies in the literature regarding EAT thickness. Iacobellis et al. (13) found that EAT thickness measured during end-systole to be minimum 1 mm and maximum 22.6 mm with a mean value of 7 mm in males and 6.5 mm in females among individuals evaluated by echocardiography for standard clinical indications (19). When measured in end-diastole, Jeong et al. (15) found a mean value of 6.38 mm (1.1-16.6 mm) in 203 individuals referred to coronary angiography, and Nelson et al. (22) found a mean of 4.7±1.5 mm in 356 asymptomatic patients. Mookadam et al. (23) stated that an EAT thickness >5 mm during end-diastole is associated with cardiac abnormalities (left atrial dilatation, lower ejection fraction, increased left ventricular mass, and diastolic dysfunction) that have been detected by echocardiography. In another study, 7.6 mm and higher values measured during end-diastole (15) and in our previous study, 5.2 mm and higher values measured in end-diastole (10) were found as threshold limit values associated with the presence of coronary artery disease. Likewise, threshold limit values for subclinical atherosclerosis (24), metabolic syndrome (19), low coronary flow reserve (16), and hypertension (11) have also been defined. Bertaso et al. (3) suggested that in systematic review measurements >5 mm should represent a relevant cutoff to define increased EAT thickness, particularly in low-risk populations. Possibly measurements >5 mm during end-diastole could be a cut-off value increased epicardial fat, but that value should be supported by a large studies.

While interpreting these threshold limit values, it should be kept in mind that EAT thickness could be influenced by age, gender, and race and whether the measurement was done during end-systole or -diastole.

Limitations to measuring epicardial adipose tissue thickness by transthoracic echocardiography

There are several limitations to the measurement of EAT thickness by transthoracic echocardiography. First, we only partially measure EAT by transthoracic echocardiography. In contrast, both EAT thickness and volume can be measured by cardiac CT and MRI precisely and more accurately than echocardiography. Echocardiographic measurements are not as reproducible as cardiac CT and MRI. Another limitation is the relatively poor inter-observer and intra-observer variability as compared with cardiac MRI and CT. The foremost limitation is the lack of certain threshold values to predict in pathologies. EAT thickness appears to increase with age, and it could be influenced with gender and ethnicity. Although EAT measurement by echocardiography has some limitations, it has the advantage of being an easy, readily available, repeatable, and low cost modality without radiation exposure.

Conclusion

EAT, which still remains a mystery despite new information determined with each passing day, can be easily, cost affectively, and reproducibly evaluated by transthoracic echocardiography. EAT assessment is still a subject of research; however, it appears to be an additional promising marker in assessing cardiovascular and metabolic risks in daily clinical practice.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks to Prof. Dr. Leyla Elif Sade for her scientific support and experiences in preparing the present manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Singh N, Singh H, Khanijoun HK, Iacobellis G. Echocardiographic Assessment of Epicardial Adipose Tissue - A Marker of Visceral Adiposity. MJM. 2007;101:26–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu FZ, Chou KJ, Huang YL, Wu MT. The relation of location-specific epicardial adipose tissue thickness and obstructive coronary artery disease:systemic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014;14:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-14-62. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertaso AG, Bertol D, Duncan BB, Foppa M. Epicardial fat:definition, measurements and systematic review of main outcomes. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2013;101:e18–28. doi: 10.5935/abc.20130138. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iacobellis G, Corradi D, Sharma AM. Epicardial adipose tissue:anatomic, biomolecular and clinical relationships with the heart. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2005;10:536–43. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0319. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sacks HS, Fain JN. Human epicardial adipose tissue:a review. Am Heart J. 2007;153:907–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.03.019. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iacobellis G, Bianco AC. Epicardial adipose tissue:emerging physiological, pathophysiological and clinical features. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2011;22:450–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2011.07.003. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iacobellis G, Ribaudo MC, Assael F, Vecci E, Tiberti C, Zappaterreno A, et al. Echocardiographic epicardial adipose tissue is related to anthropometric and clinical parameters of metabolic syndrome:a new indicator of cardiovascular risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5163e8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iacobellis G, Leonetti F. Epicardial adipose tissue and insulin resistance in obese subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:6300–2. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1087. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahn SG, Lim HS, Joe DY, Kang SJ, Choi BJ, Choi SY, et al. Relationship of epicardial adipose tissue by echocardiography to coronary artery disease. Heart. 2008;94:e7. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.118471. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eroğlu S, Sade LE, Yıldırır A, Bal U, Özbiçer S, Özgül AS, et al. Epicardial adipose tissue thickness by echocardiography is a marker for the presence and severity of coronary artery disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;19:211–7. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2008.05.002. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eroğlu S, Sade LE, Yıldırır A, Demir O, Müderrisoğlu H. Association of epicardial adipose tissue thickness by echocardiography and hypertension. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2013;41:115–22. doi: 10.5543/tkda.2013.83479. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dicker D, Atar E, Kornowski R, Bachar GN. Increased epicardial adipose tissue thickness as a predictor for hypertension:a cross-sectional observational study. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2013;15:893–8. doi: 10.1111/jch.12201. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iacobellis G, Assael F, Ribaudo MC, Zappaterreno A, Alessi G, Di Mario U, et al. Epicardial fat from echocardiography:a new method for visceral adipose tissue prediction. Obes Res. 2003;11:304e310. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaowalit N, Somers VK, Pellikka PA, Rihal CS, Lopez-Jimenez F. Subepicardial adipose tissue and the presence and severity of coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2006;186:354–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.08.004. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeong JW, Jeong MH, Yun KH, Oh SK, Park EM, Kim YK, et al. Echocardiographic epicardial fat thickness and coronary artery disease. Circ J. 2007;71:536–9. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.536. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sade LE, Eroğlu S, Bozbaş H, Özbiçer S, Hayran M, Haberal A, et al. Relation between epicardial fat thickness and coronary flow reserve in women with chest pain and angiographically normal coronary arteries. Atherosclerosis. 2009;204:580–5. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.09.038. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Momesso DIP, Bussade I, Epifanio MA, Schettino CD, Russo LA, Kupfer R. Increased epicardial adipose tissue in type 1 diabetes is associated with central obesity and metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;91:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.09.037. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mustelier JV, Rego JO, González AG, Sarmiento JC, Riverón BV. Echocardiographic parameters of epicardial fat deposition and its relation to coronary artery disease. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2011;97:122–9. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2011005000068. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iacobellis G, Willens HJ, Barbaro G, Sharma AM. Threshold values of high-risk echocardiographic epicardial fat thickness. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:887–92. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.6. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malavazos AE, Di Leo G, Secchi F, Lupo EN, Dogliotti G, Coman C, et al. Relation of echocardiographic epicardial fat thickness and myocardial fat. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:1831–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.01.368. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iacobellis G, Willens HJ. Echocardiographic epicardial fat:a review of research and clinical applications. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:1311–9. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2009.10.013. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson MR, Mookadam F, Thota V, Emani U, Al Harthi M, Lester SJ, et al. Epicardial fat:an additional measurement for subclinical atherosclerosis and cardiovascular risk stratification? J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2011;24:339–45. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.11.008. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mookadam F, Goel R, Alharthi MS, Jiamsripong P, Cha S. Epicardial fat and its association with cardiovascular risk:a cross-sectional observational study. Heart Views. 2010;11:103–8. doi: 10.4103/1995-705X.76801. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Natale F, Tedesco MA, Mocerino R, de Simone V, Di Marco GM, Aronne L, et al. Visceral adiposity and arterial stiffness:echocardiographic epicardial fat thickness reflects, better than waist circumference, carotid arterial stiffness in a large population of hypertensives. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009;10:549–55. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jep002. [CrossRef] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]