Abstract

Heavy menstrual bleeding is one of the most commonly encountered gynecological problems. While accurate objective quantification of menstrual blood loss is of value in the research setting, it is the subjective assessment of blood loss that is of greater importance when assessing the severity of heavy menstrual bleeding and any subsequent response to treatment. In this review the various approaches to objective, subjective and semi-subjective assessment of menstrual blood loss will be discussed.

Keywords: abnormal uterine bleeding, heavy menstrual bleeding, menorrhagia, menstrual blood loss

Heavy menstrual loss is one of the most commonly encountered gynecological problems, and is scientifically defined as greater than 80 ml of blood loss each period [1], however, this is rarely measured in clinical practice. The descriptions of the quantity of blood loss women experience each month is subjective and precise reporting of blood loss is difficult [2]. The previously used terms, ‘menorrhagia’ and ‘dysfunctional uterine bleeding’ have been rejected by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), who have developed the FIGO Classification of Causes of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding and use the term abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) with a suffix to represent the cause (e.g., AUB-P is used if the AUB is caused by endometrial polyps, AUB-L if it is caused by leiomyoma, among others) FIGO defines AUB as ‘bleeding that is abnormally heavy and/or abnormal in timing’ and heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) as ‘bleeding above the 95th percentile of the normal population’ [3]. When the NICE published their guidance for the treatment of HMB in 2007 they recommended that HMB be defined as excessive menstrual blood loss that interferes with the woman's physical, emotional, social and material quality of life [4]. From these recommendations the emphasis has moved from quantitative measurement to assessment of the overall effects on quality of life. However, accurately measuring the degree of blood loss remains important as it provides a valuable tool for the measurement of response to treatment, and in research, where the validity of results depends on the accuracy of blood loss measurement. Numerous methods of accurately quantifying menstrual blood loss have been developed in addition to the qualitative methods for assessing the affect heavy menstrual bleeding has on a women's quality of life. In this chapter, we will discuss these quantitative tools and their development.

Objective measurement of menstrual blood loss

Quantitative measurement of monthly menstrual loss has been widely studied and by the very nature of menstrual loss, has proven difficult to evaluate.

The methods of tampon and pad counting and the weighing of these blood-stained products has proven of little value in quantifying menstrual blood loss [5,6].

The alkaline hematin method was first described in 1942 as a method of determining hemoglobin concentrations by Clegg and King [7]. This method, which was used to describe menstrual blood loss in 1964 by Hallberg and Nilsson [8], uses menstrual pads which are collected during menstruation, and then soaked in sodium hydroxide. This converts hemoglobin to alkaline hematin, resulting in characteristic changes in the color of the solution. A venous sample of the woman's blood is incubated in parallel and the total blood loss can then be calculated using spectrometry. Diagnostic studies of the reliability of this method have found blood recovery rates of 95–105% of total blood quantities [9–11]. This method relies on all menstrual blood loss being absorbed on the pads used; any extraneous blood loss at the time of menstruation will not be recorded [12].

This method was initially developed for use in women with cotton-based feminine hygiene products. Automated extraction of hemoglobin via nonionic detergents was developed, however, this resulted in inconsistent detection of hemoglobin. Towels containing superabsorbent polymers (ultrathin), which are more effective at containing menstrual loss, release hemoglobin unreliably [13]. The overnight incubation of pads in sodium hydroxide prior to analysis has allowed the use of ultrathin products [13], however, this technique remains expensive and inconvenient for use outside of a research setting.

Another method of menstrual blood flow collection is the menstrual cup or Gynaeseal. This device consists of a latex diaphragm that collects menstrual blood. Evaluation of the menstrual cup has found that a significant proportion of women find its use unacceptable. Studies also found the collection of menstrual blood by this technique to be inaccurate due to blood spillage, which is also a potential problem when patients exchange any sanitary item [14,15].

In clinical practice, qualitative assessments have proven their impracticality in nonresearch settings. General practitioners (GP) find the precise quantification of menstrual blood loss to be a less helpful measure than the impact on a woman's quality of life [16].

Subjective reporting of blood loss

Although subjective reporting of blood loss is often thought to be a poor indicator of genuine menstrual loss, it does positively correlate with objectively measured blood loss, although the positive predictive value is low [2]. There have been numerous attempts to assess the validity of subjective reporting of menstrual loss. First, the reported number of days menstrual blood loss is positively correlated with total blood loss [17]. Second, a prospective study of women presenting with reported HMB examined the blood loss by the alkaline hematin method with the women's subjective reporting of blood loss [18]. This study found that the mean blood loss measured in the group complaining of ‘very heavy’ blood loss was significantly greater than those simply complaining of ‘heavy’ blood loss (64 and 42 ml, respectively). However, they also found that of women who rated their periods as ‘very heavy’, 25% had calculated volumes of <35 ml each month, and of women with ‘heavy’ periods 25% had a loss of >85 ml. The authors of this study also examined features such as reported clot size, measured ferritin levels and frequency of pad change, and found that by using these measures in a logistic regression model they were able to correctly predict the blood loss in 76% of the women. A further study found that of women with reported heavy menstrual bleeding, only 55.9% had blood loss greater than 80 ml [2].

Factors that may affect an individual's perception of menstrual blood loss include the number of days of bleeding, age, number of sanitary products used, menstrual incontinence or flooding [19]. A cohort study of 207 women with HMB found positive correlation between number of towels and tampons used, age, height and days of bleeding and the total measure of blood loss [20]. The authors concluded that despite these correlations, accurate quantitative assessment was difficult without objective measurement.

Although subjective reporting of heavy menstrual bleeding has been shown to be limited in its accuracy, it remains important due to the subjective nature of HMB. If a woman is sufficiently troubled by menstrual loss to request treatment it is reasonable that this should be taken seriously and treated, however, by the safest, simplest method available. This may be simple reassurance, or medical treatments to reduce the bleeding, before surgical treatments are considered. A cohort follow-up study of women with reported heavy menstrual loss, but objectively recorded normal blood loss found that by 3 years only 26% were quoted as being happy with their periods [21]. Out of the remaining women 28% had undergone surgery, 18% were taking some form of medical therapy, with the remainder either menopausal, pregnant, breastfeeding or trying to conceive. The authors of this study concluded that while some women are content with being reassured that their periods are normal, a significant number will intent on some form of medical or surgical treatment.

Semisubjective assessment of blood loss

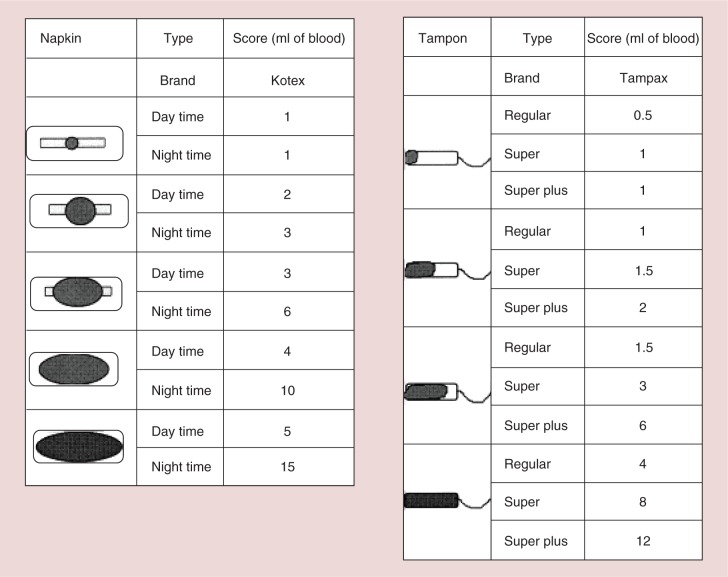

In order to improve the accuracy of blood loss assessment, visual assessment techniques have been developed. These methods use pictorial images of differing quantities of menstrual blood loss in order to inform a woman's self-assessment of her monthly loss. The pictorial blood loss assessment chart (PBAC) is a semi-quantitative assessment of blood loss by comparing the stains seen on standardized sanitary items with given diagrams (Figure 1) [22]. An initial study using this method compared objective menstrual blood loss measurements with the score obtained from PBAC, which took into account the degree to which each item of sanitary protection was soiled with blood as well as the total number of pads or tampons used. Twenty eight women were examined, comparing their PBAC with their objectively measured blood loss. This study found that a PBAC score of >100, when used as a diagnostic test for HMB, had a specificity and sensitivity of greater than 80% [22]. Over each menstrual period, each time a woman changes her tampon or pad she determines the degree of soiling by comparing with the illustrated examples on the chart (lightly, moderately or heavily). There is also space to record clots (their size equated with coinage) and episodes of flooding. Loss of blood at the time of episodes of flooding are likely to lead to an underestimation of total blood volume and can be distressing to the individual especially if in public, motivating attendance for treatment.

Figure 1.

Pictorial blood assessment chart.

Reproduced with permission from the authors (Published RCOG press) [22].

A study using the same PBAC tool in The Netherlands reported positive predictive values of up to 85.9% and negative predictive value of 84.9% and concluded that this simple tool was superior to subjective assessment alone [2]. A further validation study found a sensitivity of 97% for a score of >100, however, a low specificity of 7.5%; a positive predictive value of 62% and negative predictive value of 60% [23]. The PBAC has recently been validated for its use in the pediatric and adolescent population [24]. Thus the chart is not as accurate as menstrual hemoglobin extraction, but is superior to history taking alone and has the great advantage of not requiring laboratory facilities. It has been used in a wide range of environments including remote developing world settings.

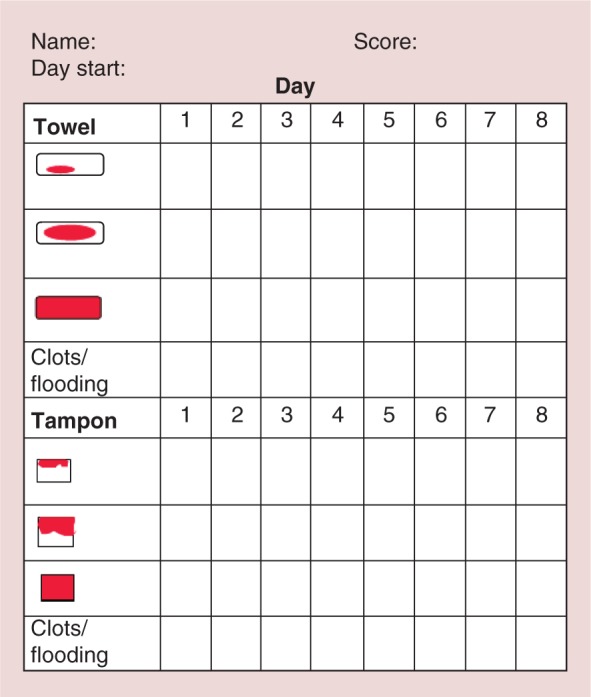

An alternative to the PBAC chart was described in 2001, using a menstrual pictogram (Figure 2) [12]. The authors of this study aimed to take into account extraneous blood loss not collected by menstrual pads.

Figure 2.

The menstrual pictogram.

Reproduced with permission from [12] © Elsevier (2001).

The menstrual pictogram uses pictures representing different levels of staining, different types of products and their relative size, for example, daytime or nighttime products, taking into account the different absorption properties of these products. Again, women were asked to describe blood lost at the time of exchanges and record the passage of clots. This method was validated using the alkaline hematin method and found that the menstrual pictogram had a sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 88% in diagnosing blood loss greater than 80 ml [12]. Contemporaneous recording on palm-held electronic devices, rather than on paper also increased the ease of data collection and analysis.

Statistical modeling of menstrual loss

In order to improve the assessment of extraneous blood loss, one study used a mixed linear model, based on entries in a menstrual diary, laboratory values of hemoglobin and ferritin and subjects age to predict monthly menstrual loss [25]. This method relied upon the change in circulating hemoglobin and ferritin as an estimate of blood lost in menstruation. As with other validation studies this method was compared with the alkaline hematin method. Using this model they were able to diagnose bleeding greater than 80 ml with a sensitivity of 87% and specificity of 70%. This study was limited by its use in a single trial, of a narrowly defined population and no further studies have as yet used this method.

Menorrhagia outcomes questionnaire

The Menorrhagia Outcomes Questionnaire was developed by Lamping et al. in order to assess women's symptoms of HMB before and following surgical treatment [26]. Using information obtained from interviews with women undergoing hysterectomy for HMB, a comprehensive literature review and existing questionnaires, the researchers categorized outcomes following surgery for HMB into symptoms, postoperative complications, quality of life and satisfaction. The questionnaire contains 26 items relating to the aforementioned categories, as well as information regarding demographics and individual treatment experiences. The Menorrhagia Outcomes Questionnaire is relatively quick to complete, is feasible to be used for monitoring women by postal survey and has been demonstrated to have met standard psychometric criteria for reliability and validity [26].

Patient-based outcome measures

Research has highlighted that the patient's experience of her symptoms is an important outcome to measure, and as a result patient-based outcome measures (PBOMs) have been developed [27]. PBOMs can be generic or disease specific, and include questionnaires and standardized interviews. The generic short form 36 (SF–36) is a generalized health-related quality of life questionnaire that has been used in studies examining the effects of HMB. An important limitation, however, is due to the intermittent nature of HMB – many women find it difficult to answer all the questions as their quality of life fluctuates depending on whether they are heavily bleeding at the time [28]. The Aberdeen Menorrhagia Severity Scale (AMSS) was developed in the UK and contains 15 items with a 4-point Likert scale for responses with a maximum score of 47 [29]. The score is then converted to a percentage producing a score from 0 to 100. This scale has been used in several studies and has been judged to be of good quality [28].

Menorrhagia multiattribute scale

The problems associated with heavy menstrual loss depend not just on the objective heaviness of the bleeding, but the degree to which this blood loss impacts on the woman's quality of life and general wellbeing. As such, validated tools to measure this impact on quality of life have been developed. One such tool is the menorrhagia multi-attribute scale (MMAS), a quality of life questionnaire that was developed with women experiencing HMB using a multi-attribute utility method [30]. This tool differed from generic quality of life questionnaires such as the generic Short Form 36 Health Survey questionnaire (SF–36), in that it specifically examined quality of life issues associated with heavy menstrual bleeding. Following interviews with women referred for the treatment of HMB, their concerns where categorized into different domains based on their answers and each domain given a rating based on its perceived importance. These domains included; practical difficulties, social life, psychological health, physical health and wellbeing, and work/daily routine and family life/relationships.

For each of these domains, women are asked to tick an answer that best applies to them. From their answers a score is calculated with a scale of 0–100. The MMAS was validated by a study as part of the ECLIPSE trial [31]. The authors found good convergent and discriminant consistency, and that it was acceptable to women, and this scale has been used subsequently in the study of thermal ablation techniques for the treatment of HMB [32].

Conclusion

There are numerous methods of quantifying menstrual blood loss, of which the alkaline hematin remains the most accurate method, however, is rarely used outside of a research setting. Pictorial-based assessments of menstrual loss are more accurate than subjective assessment alone. Assessment of the subjective quality of life issues experienced should inform management of women with HMB.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Hallberg L, Högdahl AM, Nilsson L, Rybo G. Menstrual blood loss – a population study. Variation at different ages and attempts to define normality. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 45(3), 320–351 (1966). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janssen CA, Scholten PC, Heintz AP. A simple visual assessment technique to discriminate between menorrhagia and normal menstrual blood loss. Obstet. Gynecol. 85(6), 977–982 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munro MG, Critchley HO, Fraser IS. The flexible FIGO classification concept for underlying causes of abnormal uterine bleeding. Semin. Reprod. Med. 29(5), 391–399 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NICE. Heavy Menstrual bleeding (2007). www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg44

- 5.Chimbira TH, Anderson AB, Turnbull A. Relation between measured menstrual blood loss and patient's subjective assessment of loss, duration of bleeding, number of sanitary towels used, uterine weight and endometrial surface area. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 87(7), 603–609 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rankin GL, Veall N, Huntsman RG, Liddell J. Measurement with 51Cr of red-cell loss in menorrhagia. Lancet 1(7229), 567–569 (1962). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King EJ. Alkaline ha ematin method for haemoglobin determination. Br. Med. J. 2(4521), 349 (1947). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hallberg L, Nilsson L. Determination of menstrual blood loss. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 16, 244–248 (1964). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheyne GA, Shepherd MM. Comparison of chemical and atomic absorption methods for estimating menstrual blood loss. J. Med. Lab. Technol. 27(3), 350–354 (1970). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaw ST, Aaronson DE, Moyer DL. Quantitation of menstrual blood loss-further evaluation of the alkaline hematin method. Contraception 5(6), 497–513 (1972). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Eijkeren MA, Scholten PC, Christiaens GC, Alsbach GP, Haspels AA. The alkaline hematin method for measuring menstrual blood loss-a modification and its clinical use in menorrhagia. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 22(5–6), 345–351 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wyatt KM, Dimmock PW, Walker TJ, O'Brien PM. Determination of total menstrual blood loss. Fertil. Steril. 76(1), 125–131 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magnay JL, Schönicke G, Nevatte TM, O'Brien S, Junge W. Validation of a rapid alkaline hematin technique to measure menstrual blood loss on feminine towels containing superabsorbent polymers. Fertil. Steril. 96(2), 394–398 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gleeson N, Devitt M, Buggy F, Bonnar J. Menstrual blood loss measurement with gynaeseal. Aust. NZ J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 33(1), 79–80 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng M, Kung R, Hannah M, Wilansky D, Shime J. Menses cup evaluation study. Fertil. Steril. 64(3), 661–663 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Flynn N, Britten N. Menorrhagia in general practice-disease or illness. Soc. Sci. Med. 50(5), 651–661 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snowden R, Christian B. Patterns and Perceptions of Menstruation: a World Health Organization international collaborative study in Egypt, India, Indonesia, Jamaica, Mexico, Pakistan, Philippines, Republic of Korea, United Kingdom and Yugoslavia. Croom Helm, London, UK: (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warner PE, Critchley HO, Lumsden MA, Campbell-Brown M, Douglas A, Murray GD. Menorrhagia I: measured blood loss, clinical features, and outcome in women with heavy periods: a survey with follow-up data. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 190(5), 1216–1223 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fraser IS, McCarron G, Markham R. A preliminary study of factors influencing perception of menstrual blood loss volume. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 149(7), 788–793 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higham JM, Shaw RW. Clinical associations with objective menstrual blood volume. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 82(1), 73–76 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higham J, Reid P. A preliminary investigation of what happens to women complaining of menorrhagia but whose complaint is not substantiated. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 16(4), 211–214 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higham JM, O'Brien PM, Shaw RW. Assessment of menstrual blood loss using a pictorial chart. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 97(8), 734–739 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reid PC, Coker A, Coltart R. Assessment of menstrual blood loss using a pictorial chart: a validation study. BJOG 107(3), 320–322 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanchez J, Andrabi S, Bercaw JL, Dietrich JE. Quantifying the PBAC in a pediatric and adolescent gynecology population. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 29(5), 479–484 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schumacher U, Schumacher J, Mellinger U, Gerlinger C, Wienke A, Endrikat J. Estimation of menstrual blood loss volume based on menstrual diary and laboratory data. BMC Womens Health 12, 24 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamping DL, Rowe P, Clarke A, Black N, Lessof L. Development and validation of the Menorrhagia Outcomes Questionnaire. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 105(7), 766–779 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clark TJ, Khan KS, Foon R, Pattison H, Bryan S, Gupta JK. Quality of life instruments in studies of menorrhagia: a systematic review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 104(2), 96–104 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matteson KA, Boardman LA, Munro MG, Clark MA. Abnormal uterine bleeding: a review of patient-based outcome measures. Fertil. Steril. 92(1), 205–216 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruta DA, Garratt AM, Chadha YC, Flett GM, Hall MH, Russell IT. Assessment of patients with menorrhagia: how valid is a structured clinical history as a measure of health status? Qual. Life Res. 4(1), 33–40 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaw RW, Brickley MR, Evans L, Edwards MJ. Perceptions of women on the impact of menorrhagia on their health using multi-attribute utility assessment. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 105(11), 1155–1159 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pattison H, Daniels JP, Kai J, Gupta JK. The measurement properties of the menorrhagia multi-attribute quality-of-life scale: a psychometric analysis. BJOG 118(12), 1528–1531 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Varma R, Soneja H, Samuel N, Sangha E, Clark TJ, Gupta JK. Outpatient Thermachoice endometrial balloon ablation: long-term, prognostic and quality-of-life measures. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 70(3), 145–148 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]