Abstract

Since the lipofuscin of retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells has been implicated in the pathogenesis of Best vitelliform macular dystrophy, we quantified fundus autofluorescence (quantitative fundus autofluorescence, qAF) as an indirect measure of RPE lipofuscin levels. Mean non-lesion qAF was found to be within normal limits for age. By spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) vitelliform lesions presented as fluid-filled subretinal detachments containing reflective material. We discuss photoreceptor outer segment debris as the source of the intense fluorescence of these lesions and loss of anion channel functioning as an explanation for the bullous photoreceptor-RPE detachment. Unexplained is the propensity of the disease for central retina.

Keywords: Best vitelliform macular dystrophy, BEST1, Fundus autofluorescence, Quantitative autofluorescence, SD-OCT

38.1 Introduction

The inherent fluorescence of retina originates primarily from the lipofuscin of retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells and is commonly imaged as fundus autofluorescence (AF) by confocal laser scanning ophthalmoscopy (cSLO). The lipofuscin fluorophores that have been described are vitamin A aldehyde adducts with excitation maxima from ~ 430–510 nm and peak emission of ~ 600 nm. Topographic patterns of fundus AF are well known to be altered in age-related macular degeneration, retinitis pigmentosa, acute macular disease, pattern dystrophies and Bull’s eye maculopathy (von Ruckmann et al. 1997b; Robson et al. 2006; Boon et al. 2007; Kellner et al. 2009; Michaelides et al. 2010; Gelman et al. 2012). Fundus autofluorescence intensity is particularly elevated in recessive Stargardt disease (STGD1) (Delori et al. 1995a; Lois et al. 2004; Cideciyan et al. 2005). Emission spectra recorded at the fundus in healthy eyes and in patients with STGD1 and age-related macular degeneration all exhibit emission maxima at 580–620 nm (Delori et al. 1995b; Delori et al. 1995a).

38.2 Best Vitelliform Macular Dystrophy: Clinical Findings

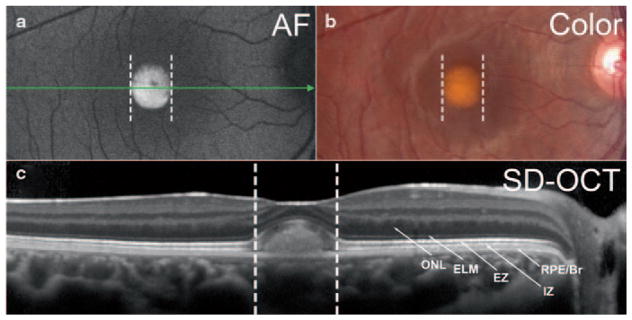

Best vitelliform macular dystrophy (BVMD) is an autosomal dominant disease associated with mutations in BEST1, the gene encoding the bestrophin-1 protein located on the basolateral membrane and within intracellular compartments of RPE cells (Petrukhin et al. 1998; Marmorstein et al. 2000). Ophthalmoscopic features of BVMD typically present in juveniles, and overt disease is most often limited to the macula (Boon et al. 2009). Aberrant responses recorded by electrooculography (EOG) can be diagnostic (Deutman 1969). The onset of the disorder is usually characterized by a central oval lesion (vitelliform lesion) that exhibits intense fluorescence in fundus AF images (Spaide et al. 2006) (Fig. 38.1a) and that is visible as a dome shaped separation between photoreceptor cells and RPE in images acquired by spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) (Querques et al. 2008; Ferrara et al. 2010) (Fig. 38.1c).

Fig. 38.1.

Multimodal imaging of a BVMD patient (age 14 years) in the vitelliform stage. Fundus autofluorescence (a), color fundus photograph (b) and horizontal SD-OCT scan (c). Corresponding positions in a, b and c are shown as dashed vertical lines. The position and horizontal extent of the SD-OCT scan (c) is indicated by the green arrow in (a). a. By fundus autofluorescence the foveal lesion exhibits an increased signal. In the SD-OCT image, a dome-shaped foveal lesion that includes a hyperreflective component is revealed. The retina appears qualitatively normal outside the lesion. Reflectivity bands in outer retina are attributed to outer nuclear layer ( ONL); external limiting membrane ( ELM); ellipsoid region of inner segment ( EZ); interdigitation zone ( IZ) and RPE/Bruch’s membrane complex ( RPE/Br) (Staurenghi et al. 2014). The area of separation is between bands attributable to EZ and RPE/Br

38.3 RPE Lipofuscin and BVMD

There have been numerous reports indicating that RPE lipofuscin is increased in BVMD. Some of these human studies have been based on non-quantitative analysis (Frangieh et al. 1982; Weingeist et al. 1982) while others acquired measurements from electron micrographs (O’Gorman et al. 1988) or biochemical analysis (Bakall et al. 2007). In some BVMD patients non-lesion posterior fundus exhibited AF levels within 2 standard deviations of age-matched controls while in most cases the entire fundus was reported to display abnormally intense AF (von Ruckmann et al. 1997a).

38.4 Quantitative Fundus Autofluorescence in Best Vitelliform Macular Dystrophy

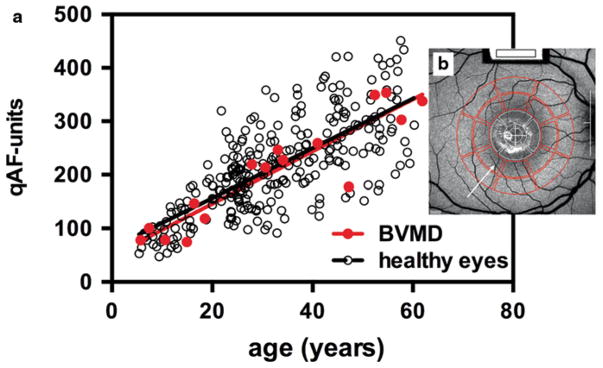

Underlying disease processes in BVMD are poorly understood and a pathway leading to increased RPE lipofuscin formation is not obvious. Thus, we undertook a disciplined approach to measuring the intensity of fundus AF outside the lesion area. To this end, short-wavelength AF images (488 nm excitation) were acquired with a cSLO (Heidelberg Spectralis, HRA+OCT; Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany). To enable comparisons amongst patients, image grey levels (GLs) were normalized to the GLs in an internal fluorescent reference (Fig. 38.2b) installed in the instrument and the sensitivity used was within the linear range of the detector (GL < 175). Additional protocol details are described in Fig. 38.2 and in published work (Delori et al. 2011).

Fig. 38.2.

Quantitative fundus autofluorescence (qAF). qAF was calculated from images (488 nm excitation) obtained from 27 eyes of 16 BVMD patients ( red circles) and 277 healthy subjects reported previously (Greenberg et al. 2013) ( black circles) and plotted as function of age (a). qAF was measured in pre-determined circularly arranged segments ( red; 8 segments/ring). (b) Mean non-lesion qAF plotted (a) are based on values obtained from outer ring (b). Mean non-lesion qAF ( solid black line in a) of healthy subjects is also shown. The segments were scaled to the distance between the temporal edge of the optic disc ( white vertical line) and the center of the fovea ( white cross) (b). Details of image acquisition and analysis are published (Delori et al. 2011)

As shown in Fig. 38.2a, qAF increased with age in both healthy eyes and in non-lesion areas of BVMD retina. Importantly, in all BVMD eyes, qAF values outside the lesion were within normal limits for age. qAF values within the lesion were elevated and the emission spectra were consistent with that of lipofuscin (Duncker et al. 2014).

38.5 What Have We Learned?

By applying the qAF approach to BVMD patients, we found that in fundus areas outside the central lesion, RPE lipofuscin levels are not increased. Thus a generalized increase in RPE lipofuscin is unlikely to contribute to the pathogenesis of BVMD. Except for the area of the lesion and an adjacent transition zone, retinal lamina appeared normal in SD-OCT scans.

The precise role of the BEST1 protein has been difficult to elucidate. Multiple anion channel functions have been attributed to BEST1 including an outward calcium-dependent chloride conductance and bicarbonate efflux (Sun et al. 2002; Rosenthal et al. 2006; Qu and Hartzell 2008; Marmorstein et al. 2009). Due to osmotic forces, the outward flux of chloride and bicarbonate across the basolateral membrane of RPE is followed by fluid transport. Mutations in BEST1 leading to the loss of anion channel activity and insufficient fluid transport could be the cause of the fluid-filled detachment between photoreceptor cells and RPE that is detected by SD-OCT. Reduced fluid flux is a feature of an induced pluripotent stem cell model of BVMD (Singh et al. 2013). Since RPE lipofuscin is well known to originate from photoreceptor outer segments (Sparrow et al. 2012), the intensely autofluorescent reflective material in the vitelliform lesion likely originates from accumulating outer segment debris within the lesion. Otherwise, increased RPE lipofuscin is unlikely to be a feature of the primary disease process.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Eye Institute EY024091 and a grant from Research to Prevent Blindness to the Department of Ophthalmology, Columbia University.

Contributor Information

Janet R. Sparrow, Department of Ophthalmology, Harkness Eye Institute, Columbia University Medical Center, 635 W. 165th Street, New York, NY 10032, USA, Department of Pathology and Cell Biology, Columbia University Medical Center, 635 W. 165th Street, New York, NY 10032, USA

Tobias Duncker, Department of Ophthalmology, Harkness Eye Institute, Columbia University Medical Center, 635 W. 165th Street, New York, NY 10032, USA.

Russell Woods, Department of Ophthalmology, Harvard Medical School, Schepens Eye Research Institute, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

François C. Delori, Department of Ophthalmology, Harvard Medical School, Schepens Eye Research Institute, Boston, MA 02114, USA

References

- Bakall B, Radu RA, Stanton JB, et al. Enhanced accumulation of A2E in individuals homozygous or heterozygous for mutations in BEST1 (VMD2) Exp Eye Res. 2007;85:34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boon CJ, van Schooneveld MJ, den Hollander AI, et al. Mutations in the peripherin/RDS gene are an important cause of multifocal pattern dystrophy simulating STGD1/fundus flavimaculatus. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:1504–1511. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.115659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boon CJ, Klevering BJ, Leroy BP, et al. The spectrum of ocular phenotypes caused by mutations in the BEST1 gene. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2009;28:187–205. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cideciyan AV, Swider M, Aleman TS, et al. ABCA4-associated retinal degenerations spare structure and function of the human parapapillary retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4739–4746. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delori FC, Staurenghi G, Arend O, et al. In vivo measurement of lipofuscin in Stargardt’s disease—fundus flavimaculatus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995a;36:2327–2331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delori FC, Dorey CK, Staurenghi G, et al. In vivo fluorescence of the ocular fundus exhibits retinal pigment epithelium lipofuscin characteristics. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995b;36:718–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delori F, Greenberg JP, Woods RL, et al. Quantitative measurements of autofluorescence with the scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:9379–9390. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutman AF. Electro-oculography in families with vitelliform dystrophy of the fovea. Detection of the carrier state. Arch Ophthalmol. 1969;81:305–316. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1969.00990010307001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncker T, Greenberg JP, Ramachandran R, et al. Quantitative fundus autofluorescence and optical coherence tomography in best vitelliform macular dystrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:1471–1482. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara DC, Costa RA, Tsang SH, et al. Multimodal fundus imaging in best vitelliform macular dystrophy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010;248:1377–1386. doi: 10.1007/s00417-010-1381-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frangieh GT, Green R, Fine SL. A histopatholgic study of best’s macular dystrophy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100:1115–1121. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1982.01030040093017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman R, Chen R, Blonska A, et al. Fundus autofluorescence imaging in a patient with rapidly developing scotoma. Retinal Cases Brief Reports. 2012;6:345–348. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0b013e318260af5d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JP, Duncker T, Woods RL, et al. Quantitative fundus autofluorescence in healthy eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:6820–6826. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellner U, Kellner S, Weber BH, et al. Lipofuscin- and melanin-related fundus autofluorescence visualize different retinal pigment epithelial alterations in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:1349–1359. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lois N, Halfyard AS, Bird AC, et al. Fundus autofluorescence in stargardt macular dystrophy-fundus flavimaculatus. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein AD, Marmorstein LY, Rayborn M, et al. Bestrophin, the product of the best vitelliform macular dystrophy gene (VMD2), localizes to the basolateral plasma membrane of the retinal pigment epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:12758–12763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220402097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein A, Cross HE, Peachey NS. Functional roles of bestrophins in ocular epithelia. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2009;28:206–226. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelides M, Gaillard MC, Escher P, et al. The PROM1 mutation p.R373C causes an autosomal dominant bull’s eye maculopathy associated with rod, rod-cone, and macular dystrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:4771–4780. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Gorman S, Flaherty WA, Fishman GA, et al. Histopathological findings in best’s vitelliform macular dystrophy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988;106:1261–1268. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1988.01060140421045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrukhin K, Koisti MJ, Bakall B, et al. Identification of the gene responsible for best macular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1998;19:241–247. doi: 10.1038/915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Z, Hartzell HC. Bestrophin Cl− channels are highly permeable to HCO3−. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C1371–C1377. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00398.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querques G, Regenbogen M, Quijano C, et al. High-definition optical coherence tomography features in vitelliform macular dystrophy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:501–507. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson AG, Saihan Z, Jenkins SA, et al. Functional characterisation and serial imaging of abnormal fundus autofluorescence in patients with retinitis pigmentosa and normal visual acuity. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:472–479. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.082487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R, Bakall B, Kinnick T, et al. Expression of bestrophin-1, the product of the VMD2 gene, modulates voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in retinal pigment epithelial cells. FASEB J. 2006;20:178–180. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4495fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Ruckmann A, Fitzke FW, Bird AC. In vivo fundus autofluorescence in macular dystrophies. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997a;115:609–615. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100150611006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Ruckmann A, Fitzke FW, Bird AC. Fundus autofluorescence in age-related macular disease imaged with a laser scanning ophthalmoscope. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997b;38:478–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Shen W, Kuai D, et al. iPS cell modeling of best disease: insights into the pathophysiology of an inherited macular degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:593–607. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaide RF, Noble K, Morgan A, et al. Vitelliform macular dystrophy. Ophthalmol. 2006;113:1392–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow JR, Gregory-Roberts E, Yamamoto K, et al. The bisretinoids of retinal pigment epithelium. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2012;31:121–135. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staurenghi G, Sadda S, Chakravarthy U, et al. Proposed lexicon for atomic landmarks in normal posterior segment spectral-domain optical coherence tomography: the IN*OCT consensus. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:1572–1578. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Tsunenari T, Yau KW, et al. The vitelliform macular dystrophy protein defines a new family of chloride channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4008–4013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052692999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weingeist TA, Kobrin JL, Watzke RC. Histopathology of best’s macular dystrophy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100:1108–1114. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1982.01030040086016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]