Abstract

Please cite this paper as: Cappelle et al. (2012) Circulation of avian influenza viruses in wild birds in Inner Niger Delta, Mali. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses 6(4), 240–244.

Background Avian influenza viruses (AIV) have been detected in wild birds in West Africa during the northern winter, but no information is available on a potential year‐round circulation of AIV in West Africa. Such year‐round circulation would allow reassortment opportunities between strains circulating in Afro‐tropical birds and strains imported by migratory birds wintering in West Africa.

Objective and Method A 2‐year longitudinal survey was conducted in the largest continental wetland of West Africa, the Inner Niger Delta in Mali, to determine the year‐round circulation of AIV in wild birds.

Results and Conclusions Avian influenza virus RNA was detected during all periods of the year. Very low prevalence was detected during the absence of the migratory wild birds. However, a year‐round circulation of AIV seems possible in West Africa, as shown in other African regions. West Africa may hence be another potential site of reassortment between AIV strains originating from both Afro‐tropical and Eurasian regions.

Keywords: Africa, ecological drivers, epidemiology, persistence, prevalence, serology

Introduction

West Africa is a major wintering area for the natural reservoirs of avian influenza viruses (AIV), that is, migratory waterbirds (Anseriformes and Charadriiformes) breeding across Eurasia. 1 , 2 Several millions of these Eurasian migratory birds congregate in West African wetlands from October to April were they mix with Afro‐tropical waterbirds remaining in sub‐Saharan Africa throughout the year. West African wetlands may hence constitute ecosystems of perpetuation of AIV during northern winter, a period when AIV is rare in waterbirds wintering in Europe (2), but also ecosystems of emergence of new AIV through reassortment between AIV strains from different geographic origins. 2

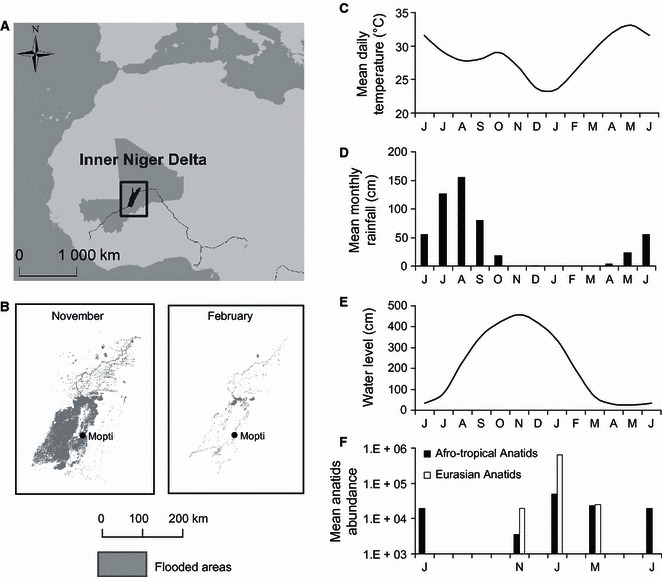

The detection and isolation of AIV in several waterbird species in West Africa in previous studies indicate that environmental conditions are favorable for the transmission of AIV in this region. 3 , 4 , 5 Surveys had been, however, restricted so far to the period when Eurasian migratory birds are present in West Africa; therefore, the potential perpetuation of AIV in West Africa through a year‐round circulation in Afro‐tropical waterbirds remains questioned. The main objective of this study is to address this question of a potential year‐round circulation of AIV in wild birds residing in West Africa. Here, we present results from a 2‐year longitudinal survey of AIV in wild birds in the largest continental wetland of West Africa, the Inner Niger Delta (IND) in Mali (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Localization and seasonal pattern of some ecological and environmental features of the Inner Niger Delta (IND) in Mali. (A) Localization of the IND in West Africa, (B) extension of the IND flooded areas (estimated for water levels of 429cm in November and 166cm in February), 1 (C) mean daily temperature from the World Climate Dataset, 8 (D) mean monthly total rainfall from the World Climate Dataset, 8 (E) mean water level of the Niger River measured at a reference point in the central part of the IND, 1 (F) population size (log scale) of Eurasian and Afro‐tropical Anatids estimated by aerial census conducted in January, March, June, and November. 1

Methods

The IND supports large populations of waterbirds species including up to several million migratory waterbirds including up to one million migrating Eurasian ducks. 1 The seasonal dynamics of waterbirds population in the IND is marked by three main drivers: (i) seasonal rainfalls (c. July–September), (ii) a seasonal flooding of the Niger River (usually peaking locally in November), and (iii) the staging of Eurasian migratory birds (c. September to April) (Figure 1). 1 Our study was conducted in 2008 and 2009 during three main periods: (i) in June, at the end of the dry season after the departure of the Eurasian migrants when Afro‐tropical waterbirds aggregate at permanent water bodies, (ii) in September, at the end of the rainy season, before the major arrival of Eurasian migrants, and (iii) in January–March when Eurasian and Afro‐tropical waterbirds mix and congregate in response to the seasonal decrease in water level.

A total of 2882 wild birds were sampled, consisting mostly in Anseriformes and Charadriiformes (Table 1). Cloacal, oropharyngeal, and serum samples were collected from live‐caught birds captured using mist nets, from recently killed birds provided by traditional hunters or from fresh droppings collected at roosting sites. Additional samples (n = 1647 wild birds) collected in the IND during previous surveys in January 2006 3 and February 2007 are also presented for comparison (Table 1). The same procedures for collecting, storing, and shipping samples were followed in these two previous campaigns, but no oropharyngeal samples were collected in January 2006. Cloacal, oropharyngeal, and fecal samples were analyzed at CIRAD laboratory in Montpellier, France. The samples were all screened by real‐time RT‐PCR (rRT‐PCR) based on the M gene of AIV as recommended by the reference laboratory of the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE). Samples with a Ct value below 35 were considered positives, and samples with a Ct value between 35 and 36 and with a sigmoid curve of fluorescence were considered as weak positives. All positive samples were subsequently processed for virus isolation by using standard methods. Serum samples were analyzed at Laboratoire Central Vétérinaire in Bamako, Mali, and at CIRAD laboratory in Montpellier, France, using the same ELISA test (FlockCheck AI MultiS‐Screen Antibody Test Kit; IDEXX Laboratories, Westbrook, ME, USA) that has successfully been used to detect AIV antibodies in wild birds. 6

Table 1.

Number of birds tested for avian influenza viruses by RT‐PCR per group of species, per season, and per year for Eurasian birds and for Afro‐tropical birds. All the birds were captured in the Inner Niger Delta, Mali. The number of birds tested positive for avian influenza viruses (AIV) is indicated in brackets, and the prevalence is given with the 95% confidence interval

| Bird group | Year | January–March | June | September–October | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. tested (no. positive) | Prevalence (CI 95%) | No. tested (no. positive) | Prevalence (CI 95%) | No. tested (no. positive) | Prevalence (CI 95%) | ||

| Eurasian anatids | 2006 | 428 (24)* | 5·6% (3·8–8·2) | ||||

| 2007 | 944 (33)* | 3·5% (2·5–4·9) | |||||

| 2009 | 14 (1)* | 7·1% (0·4–31 | |||||

| Eurasian waders | 2006 | 141 (4)* | 2·8% (1·1–7·1) | ||||

| 2007 | 51 (1)* | 2·0% (0·1–10) | |||||

| 2009 | 134 (0) | 0 (0–2·8) | |||||

| Eurasian terns | 2009 | 249 (1)* | 0·4% (0–2·2) | ||||

| Total Eurasian birds | 1961 (64)* | ||||||

| Afro‐tropical anatids | 2006 | 67 (3)** | 4·5% (1·5–12·3) | ||||

| 2007 | 16 (0) | 0 (0–19·3) | |||||

| 2008 | 589 (1)** | 0·2% (0–0·9) | 305 (0) | 0 (0–1·2) | |||

| 2009 | 15 (0) | 0 (0–20·4) | 120 (0) | 0 (0–3·1) | 82 (0) | 0 (0–4·5) | |

| Afro‐tropical waders | 2008 | 85 (0) | 0 (0–4·3) | ||||

| 2009 | 105 (0) | 0 (0–3·5) | 83 (0) | 0 (0–4·4) | 36 (0) | 0 (0–9·6) | |

| Afro‐tropical ardeids | 2008 | 30 (0) | 0 (0–11·3) | ||||

| 2009 | 44 (0) | 0 (0–8·0) | 94 (0) | 0 (0–3·9) | |||

| Afro‐tropical rails | 2006 | 34 (3)*** | 8·8% (3·0–23) | ||||

| 2008 | 57 (0) | 0 (0–6·3) | |||||

| 2009 | 117 (0) | 0 (0–3·2) | 120 (0) | 0 (0–3·1) | |||

| Afro‐tropical passerines | 2009 | 99 (0) | 0 (0–3·7) | 69 (0) | 0 (0–5·3) | 212 (1)**** | 0·5% (0–2·6) |

| Other Afro‐tropical waterbirds | 2009 | 40 (0) | 0 (0–8·8) | 94 (0) | 0 (0–3·9) | ||

| Total Afro‐tropical# Birds | 537 (6)** | 1247 (1)*** | 729 (1)*** | ||||

*AIV‐positive species: Garganey (Anas querquedula), Northern Pintail (Anas acuta), Ruff (Philomachus pugnax), Spotted Redshank (Tringa erythropus), and Gull‐billed Tern (Gelochiledon nilotica).

**Comb Duck (Sarkidiornis melanotos) and White‐faced Duck (Dendrocygna viduata).

***Common Moorhen (Gallinula chloropus) and Purple Swamphen (Porphyrio porphyrio).

****Red‐billed Quelea (Quelea quelea).

Results and discussion

Most of the birds found rRT‐PCR positive for AIV were Eurasian migrants, including ducks, waders, and terns (Table 1). AIV RNA was detected in Afro‐tropical birds in each of the three seasons considered, but prevalence was very low (<1%) at the time when Eurasian migratory birds were absent or rare, both at the end of the dry season (June) and at the end of the wet season (September). Higher prevalence was detected in Afro‐tropical anatids during the sampling period when Eurasian migrants were present (January–March). Serological results confirmed the circulation of AIV in Afro‐tropical waterbirds at a relatively low level but are not informative on any seasonal pattern in AIV circulation because serological tests detect past AIV circulation only (Table 2). Birds from various Afro‐tropical species (n = 5), which represent different ecological guilds (anatids, rails, ibises, and passerines), were found positive for AIV by molecular or serological diagnostics, suggesting that AIV circulate in a wide range of the Afro‐tropical bird community. No virus could be isolated from the PCR‐positive samples during the longitudinal study.

Table 2.

Number of birds tested for avian influenza viruses by serology (ELISA test) for different groups of birds in 2009. The dates of sampling of the birds were not indicated because serological tests detect past avian influenza viruses (AIV) circulation only

| Tested | AIV Positive | Seroprevalence (%) | CI 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eurasian anatids | 13 | 5* | 38·5 | 17·7–64·5 |

| Eurasian waders | 200 | 0 | 0 | 0–1·9 |

| Afro‐tropical anatids | 27 | 4** | 14·8 | 5·9–32·5 |

| Afro‐tropical waders | 109 | 0 | 0 | 0–3·4 |

| Other Afro‐tropical waterbirds | 109 | 1*** | 0·9 | 0·1–5·0 |

| Afro‐tropical passerines | 158 | 0 | 0 | 0–2·4 |

*Garganey (Anas querquedula).

**White‐faced Duck (Dendrocygna viduata).

***Glossy Ibis (Plegadis falcinellus).

Our results reveal that AIV can circulate year‐round within a West African wetland, with a higher prevalence when Eurasian migrants are present. This seasonal variation in AIV prevalence among wild birds may be related to several ecological and environmental factors.

First, the duration of persistence of AIV in the environment has been shown experimentally to be dependent on water temperatures. 7 As shown in Figure 1(C), West African wetlands are exposed to the highest temperatures during the period when Eurasian migratory birds are absent (average daily temperatures of 30°C from May to September), while temperatures are minimal during the period when they winter in Africa (average daily temperatures of 23·6°C during December and January, the coldest months of the year). 8 Temperature may thus constrain the environmental persistence and transmission of AIV to wild birds during part of the year. Second, the increase in the local waterbird density during the northern winter period may promote AIV transmission. The number of waterbird in the IND increases considerably with the arrival of Eurasian migrants, in particular migratory wildfowl (Figure 1F). 1 Moreover, it is worth noting that a large majority of the migratory wildfowl wintering in West Africa are ducks of the Anas genus, a group of species that consistently show the highest AIV prevalence among wild birds. 2 , 9 This massive arrival of Eurasian migrants is followed during the second half of their wintering period by the concentration of waterbirds on remnant water bodies because of decreasing water levels and the reduction in the surface of wetland habitat (Figure 1B,E). These factors increase the bird density and as a consequence the potential AIV transmission through a higher contact rate between wild birds. 10 Conversely, most Afro‐tropical waterbirds disperse after the onset of the rainy season (in July) to breed outside of the IND, leading to a decrease in the local host density.

Finally, the presence of immunologically naïve bird in the host community is considered an important driver of the transmission dynamics of AIV. 9 , 11 Most of the Afro‐tropical waterbirds species of the IND breed during the rainy season or during the early dry season. 12 At the time when Eurasian migrants leave the IND, most of the Afro‐tropical juvenile birds are between 5 and 9 month old, therefore may have been already exposed to the virus and acquire a partial immunity to AIV reinfection.

A combination of favorable factors including cooler temperatures, higher abundance of waterbirds (in particular dabbling ducks of the Anas genus), and congregation of waterbirds as wetlands availability reduces during the dry season, may promote AIV circulation in West Africa during the northern winter period.

Our study suggests that Eurasian Anatids play a major role in the dynamic of AIV in West Africa. Their arrival constitutes both a massive influx of highly competent hosts and a potential source of introduction of AIV in Afro‐tropical ecosystems. However, our detection of AIV in wild birds during all periods of the year, although at a very low prevalence, also suggests that AIV may persist in Afro‐tropical region after the departure of Eurasian migrants. This potential year‐round perpetuation of AIV in an Afro‐tropical ecosystem is consistent with the recent findings of a continuous circulation of AIV in waterbirds in southern Africa. 13 However, the low AIV prevalences measured on the field despite significant sampling efforts make it difficult to establish further conclusions.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the people that helped collecting the samples in Mali, agents of the Direction Régionale des Eaux et Forêts de Mopti, agents of the Direction Régionale des Services Vétérinaire de Mopti, and Benjamin Vollot. We also thank all the people that helped testing the samples, agents of the Laboratoire Central Vétérinaire in Bamako, and Colette Grillet in CIRAD laboratory in Montpellier. This work was supported by the GRIPAVI project sponsored by grants from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

References

- 1. Zwarts L, Bijlsma RG, van der Kamp J, Wymenga E. Living on the Edge: Wetlands and Birds in a Changing Sahel. Zeist, The Netherlands: NNV Publishing, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Olsen B, Munster VJ, Wallensten A et al. Global patterns of influenza A virus in wild birds. Science 2006; 312:384–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gaidet N, Dodman T, Caron A et al. Avian influenza viruses in water birds, Africa. Emerg Infect Dis 2007; 13:626–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gaidet N, Cattoli G, Hammoumi S et al. Evidence of infection by H5N2 highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses in healthy wild waterfowl. PLoS Pathog 2008; 4: e1000127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Snoeck CJ, Adeyanju AT, De Landtsheer S et al. Reassortant low pathogenic avian influenza H5N2 viruses in African wild birds. J Gen Virol 2011;vir.0.029728–029720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brown JD, Stallknecht DE, Berghaus RD et al. Evaluation of a commercial blocking ELISA as a serologic assay for detecting avian influenza virus infection in multiple experimentally infected avian species. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2009;CVI.00084‐00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stallknecht DE, Goekjian VH, Wilcox BR, Poulson RL, Brown JD. Avian influenza virus in aquatic habitats: what do we need to learn? Avian Dis 2010; 54:461–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Climate (2010). http://www.climate‐charts.com .

- 9. Munster VJ, Baas C, Lexmond P et al. Spatial, temporal, and species variation in prevalence of influenza A viruses in wild migratory birds. PLoS Pathog 2007; 3:e61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cappelle J, Girard O, Fofana B, Gaidet N, Gilbert M. Ecological modeling of the spatial distribution of wild waterbirds to identify the main areas where avian influenza viruses are circulating in the Inner Niger Delta, Mali. EcoHealth 2010; 7:283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Begon M, Telfer S, Smith MJ et al. Seasonal host dynamics drive the timing of recurrent epidemics in a wildlife population. Proc Biol Sci 2009; 276:1603–1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brown LH, Urban EK, Newman K. The Birds of Africa. London: Academic Press, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Caron A, Abolnik C, Mundava J et al. Persistence of low pathogenic avian influenza virus in waterfowl in a southern african ecosystem. EcoHealth 2010; 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]