Abstract

The neonatal period of very preterm infants is often characterized by a difficult adjustment to extrauterine life, with an inadequate nutrient supply and insufficient levels of growth factors, resulting in poor growth and a high morbidity rate. Long-term multisystem complications include cognitive, behavioral, and motor dysfunction as a result of brain damage as well as visual and hearing deficits and metabolic disorders that persist into adulthood. Insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF-1) is a major regulator of fetal growth and development of most organs especially the central nervous system including the retina. Glucose metabolism in the developing brain is controlled by IGF-1 which also stimulates differentiation and prevents apoptosis. Serum concentrations of IGF-1 decrease to very low levels after very preterm birth and remain low for most of the perinatal development. Strong correlations have been found between low neonatal serum concentrations of IGF-1 and poor brain and retinal growth as well as poor general growth with multiorgan morbidities, such as intraventricular hemorrhage, retinopathy of prematurity, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and necrotizing enterocolitis. Experimental and clinical studies indicate that early supplementation with IGF-1 can improve growth in catabolic states and reduce brain injury after hypoxic/ischemic events. A multicenter phase II study is currently underway to determine whether intravenous replacement of human recombinant IGF-1 up to normal intrauterine serum concentrations can improve growth and development and reduce prematurity-associated morbidities.

Keywords: fetus, preterm infant, postnatal growth, IGF-1, metabolism, preterm morbidity

Insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF-1) is an anabolic hormone with mitogenic, differentiating, antiapoptotic, and metabolic effects.1 It exerts its actions in endocrine, paracrine, and autocrine manners mediated through the IGF-1 receptor and the insulin receptor (although with a substantially less affinity with the insulin receptor). IGF-1 plays many roles which differ depending on factors such as source,2 target cell type, and developmental stage.3 Six binding proteins (IGFBP) control IGF-1 actions. Approximately 80% of IGF-1 is bound to IGFBP-3 which together with an acid-labile subunit maintains a reservoir of IGF-1 in the circulation.4,5 IGFBP-1 serum levels increase after fasting and during hypoxia, which restrains growth by decreasing the IGF-1 bioavailability.6

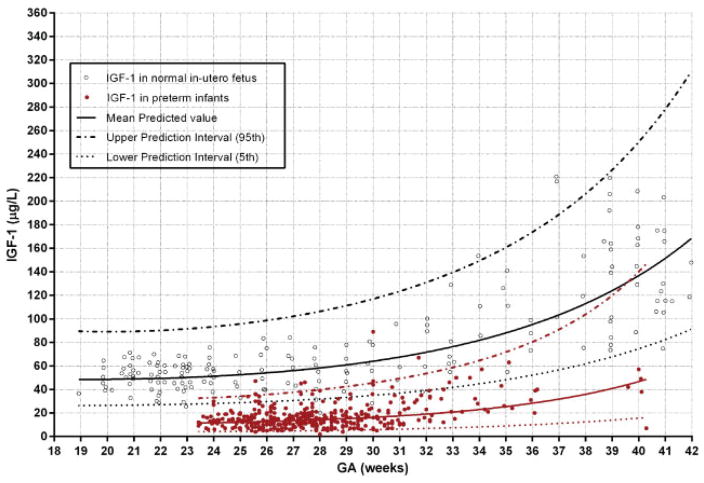

The placenta secretes IGF-1 throughout gestation and IGF-1stimulates the placental transfer of essential nutrients from the mother to the fetus.7 It is not clear whether placental derived IGF-I is secreted into the fetal circulation.8 During gestation, fetal circulating IGF-1 increases (Fig. 1) and at term birth, cord serum IGF-1 concentrations are positively associated with fetal size and fat mass.9 Late in gestation circulating IGF-1 is mainly derived from the liver, although virtually all human fetal tissues express IGF-1 from an early stage of development.10 The amniotic fluid contains higher IGF-1 concentrations than cord blood during gestation or at delivery and is swallowed by the fetus, and this source is missing after preterm birth.11

Fig. 1.

Normal intrauterine insulinlike growth factor 1 concentrations obtained from the umbilical cord with cordocentesis over 18 to 42 weeks of gestational age (unfilled circles) (n = 174)41,42 compared with preterm infants of matched postmenstrual ages (filled circles)32,43 from Hellström et al.38

Genetic defects of IGF-1 are very rarely reported in term infants suggesting that loss of functional defects is lethal. The few cases reported of genetic IGF-1 abnormalities, which may have a partial IGF-1 function, have severe intrauterine growth restriction as well as microcephaly, sensorineural deafness, developmental delay, and metabolic abnormalities.12

After very preterm birth, IGF-1 serum concentrations decrease substantially to an average of 10 ng/mL compared with an average of > 50 ng/mL in utero at postmenstrual age (PMA) 23 to 30 weeks.13 Persistent low IGF-1 levels after preterm birth are associated with poor general growth and poor brain growth as well as neonatal morbidities such as intraventricular hemorrhage, retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), and necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC).14

Metabolism

During gestation, fetal serum IGF-1 concentrations are regulated by the supply of nutrients from the mother at a time when energy is mainly derived by glycolysis. After birth, energy requirements increase compared with those in the womb. In very preterm infants this deficit is exacerbated by the loss of the maternal supply of nutrients and growth factors. In addition, nutrient assimilation is compromised and the capacity for oxidative phosphorylation of lipids for energy is limited by immaturity and the switch from glycolytic to oxidative metabolism is delayed.15 After birth very preterm infants generally accumulate a large energy deficit which is multifactorial in origin and associated with postnatal growth restriction, low IGF-1 and deranged glucose metabolism with insulin resistance and hyperglycemia. Serum IGF-1 concentrations are not associated with nutrient intake until after 30 weeks PMA possibly due to the deficient assimilation of nutrients in these immature infants.16 Lack of IGF-1 may cause or exacerbate many metabolic defects as the metabolic effects of IGF-1 overlap with those of insulin and include stimulation of amino acid and glucose uptake in skeletal muscle, differentiation of preadipocytes and reduction of hepatic glucose production.17

Preterm infants are prone to develop metabolic syndrome later in life. A risk factor for later development of metabolic syndrome, such as lower insulin sensitivity, increased blood pressure, and increased fat mass in childhood and young adulthood have been reported after preterm birth. In addition, early IGF-1 predicts lumbar spine bone mass.18

Vascularization

Proper vascularization is essential for the normal supply of oxygen, nutrients, and other factors to developing tissues. Since blood vessels in the eye are available for direct inspection and the retina may be severely affected by very preterm birth, much research has focused on retinal vascularization, which may reflect the development of other neural and vascular beds.

Vascular endothelial cells are involved in the control of vessel formation. IGF-1 promotes amino acid and glucose uptake and stimulates migration in microvessel endothelial cells. Hypoxia is a major angiogenic stimulus which upregulates vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and stimulates proliferation and maturation of vascular endothelium. IGF-1 induces VEGF-1 synthesis.19 Minimal levels of IGF-1 are required for activation by VEGF of pathways promoting retinal vascular endothelial cell proliferation and survival.20 Impaired normal neonatal angiogenesis resulting in hypoxia followed by increased hypoxia-induced pathological angiogenesis is a hallmark of ROP, but might apply to BPD21 and encephalopathy of prematurity22 as well. Thus, it is likely that low IGF-1 after preterm birth affects many vascular beds. Accordingly, low neonatal IGF-1/IGFBP-1 ratios and severe ROP have been associated with higher blood pressure in prematurely born 4-year olds.23

General Growth

Abundant genetic and experimental evidence suggests that IGF-1 is an important determinant of fetal and postnatal growth.24 IGF-1 null mice have a birth weight 60% less than normal25 and they continue to grow at a slow rate and achieve only 30% of normal weight as adults.26 In preterm infants, the neonatal period is a critical time for growth. Despite increases in nutrition, postnatal growth remains poor, particularly during the first month of life.27 Very preterm infants tend to have profound growth retardation from birth until around 30 to 32 weeks PMA followed by accelerated growth. Poor perinatal weight gain and low IGF-1 are associated with poor short- and long-term outcomes.28

Brain

During development, IGF-1 is abundantly expressed in many brain areas. However, once the brain is formed IGF-1 expression is limited to a few regions and is expressed at very low levels. The IGF-1 receptor is widely distributed in most tissues while the IGFBPs appear in specific anatomic locations. Circulating IGF-1 enters the brain, passing the blood–brain barrier. IGF-1 modulates the permeability of this barrier to other systemic neuroactive proteins. Circulating and locally produced IGF-1 are thought to have separate roles. Circulating IGF-1 provides a metabolic proprioceptive signal to brain centers in charge of adaptation to internal environmental conditions. Systemic IGF-1 is involved in brain plasticity. IGF-1 increases the activity of other growth factors such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor and VEGF but there is no evidence of stimulation of IGF-1 by other growth factors.29 In the third trimester, brain size and complexity increase dramatically. Glucose metabolism in the developing brain is regulated by IGF-1,30 which promotes brain cell proliferation, neurogenesis, myelination, maturation, and differentiation and prevents apoptosis.31

In very preterm infants, serum IGF-1 concentrations from birth to a PMA of 35 weeks correlate with brain volume, unmyelinated white matter volume, gray matter volume, and cerebellar volume estimated using volumetric magnetic resonance imaging at term age.32 In addition, lower IGF-1 during early postnatal life correlates with subnormal mental development.33

Eye

Retinopathy of prematurity is a neurovascular developmental disorder which causes blindness or visual impairment in approximately 20,000 infants worldwide per year.34 Normal retinal vascularization proceeds through the third trimester and is completed around the term. After very preterm birth, retinal blood vessels growth is retarded during the first phase of the disease. Later, the maturating peripheral retina becomes hypoxic and in severe cases during the second phase, uncontrolled retinal angiogenesis takes place after approximately 30 to 32 weeks PMA. Low IGF-1 concentrations and poor early weight gain during the first phase correlate strongly with the severity of ROP and can be used to predict sight-threatening ROP.35

Lung

In mice, IGF-1 is critical for prenatal lung organogenesis and growth. After birth before 28 gestational weeks, the development of lung alveoli and their capillary bed has just started. In autopsy studies, reduced pulmonary microvascularization has been found in infants dying from BPD. However, in infants surviving prolonged ventilation, a transient decrease in endothelial cell proliferation is followed by a brisk proliferative response36 similar to the response in severe ROP.

In extremely preterm neonates, lower neonatal IGF-1 concentrations are correlated with later development of BPD independent of gestational age and birth weight standard deviation score.37

Human and Experimental Insulinlike Growth Factor 1 Supplementation Studies

Experimental and human studies indicate that growth and development can be promoted by IGF-1 infusion in undernutrition and catabolic states.38 The role of IGF-1 in metabolism was demonstrated in a mouse model with liver-specific IGF-1 deficiency resulting in a 75% reduction in circulating IGF-1. In these mice, treatment with IGF-1 improved insulin sensitivity.39 In rabbits, intrauterine growth restriction due to placental insufficiency is corrected with an intraplacental injection of IGF-140 and in rats with hypoxic–ischemic brain injury IGF-1 treatment reduces neuronal loss. Mice treated with IGF-1 in a mouse model of ROP develop less retinopathy.

Conclusion

We hypothesize that supplementing very preterm infants with IGF-1 to normal intrauterine levels during the neonatal period will improve metabolism, growth, and brain development and prevent prematurity-related morbidities. A multi-center phase II study testing this hypothesis will soon be completed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the European Commission FP7 project 305485 PREVENT-ROP.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Prevention of retinopathy of prematurity by administering insulinlike growth factor 1 are covered by the patent owned by or licensed to Premacure AB, Uppsala, Sweden. A. H., D. L., I. H. P., and A. L. H. own shares in the company with financial interest in Premacure AB. A. H., D. L., I. H. P., B. H., and L. E. H. S. work as consultants for Shire Pharmaceuticals (Shire, Lexington, MA).

References

- 1.Laviola L, Natalicchio A, Perrini S, Giorgino F. Abnormalities of IGF-I signaling in the pathogenesis of diseases of the bone, brain, and fetoplacental unit in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295(5):E991–E999. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90452.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohlsson C, Mohan S, Sjögren K, et al. The role of liver-derived insulin-like growth factor-I. Endocr Rev. 2009;30(5):494–535. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torres-Aleman I, Villalba M, Nieto-Bona MP. Insulin-like growth factor-I modulation of cerebellar cell populations is developmentally stage-dependent and mediated by specific intracellular pathways. Neuroscience. 1998;83(2):321–334. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajaram S, Baylink DJ, Mohan S. Insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins in serum and other biological fluids: regulation and functions. Endocr Rev. 1997;18(6):801–831. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.6.0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Firth SM, Baxter RC. Cellular actions of the insulin-like growth factor binding proteins. Endocr Rev. 2002;23(6):824–854. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verhaeghe J, Van Herck E, Billen J, Moerman P, Van Assche FA, Giudice LC. Regulation of insulin-like growth factor-I and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 concentrations in preterm fetuses. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(2):485–491. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baumann MU, Schneider H, Malek A, et al. Regulation of human trophoblast GLUT1 glucose transporter by insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8):e106037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiden U, Glitzner E, Hartmann M, Desoye G. Insulin and the IGF system in the human placenta of normal and diabetic pregnancies. J Anat. 2009;215(1):60–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.01035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kadakia R, Ma M, Josefson JL. Neonatal adiposity increases with rising cord blood IGF-1 levels. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2016;85(1):70–75. doi: 10.1111/cen.13057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han VK, Lund PK, Lee DC, D’Ercole AJ. Expression of somatomedin/insulin-like growth factor messenger ribonucleic acids in the human fetus: identification, characterization, and tissue distribution. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;66(2):422–429. doi: 10.1210/jcem-66-2-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bona G, Aquili C, Ravanini P, et al. Growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-I and somatostatin in human fetus, newborn, mother plasma and amniotic fluid. Panminerva Med. 1994;36(1):5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Netchine I, Azzi S, Le Bouc Y, Savage MO. IGF1 molecular anomalies demonstrate its critical role in fetal, postnatal growth and brain development. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;25(1):181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansen-Pupp I, Hellström-Westas L, Cilio CM, Andersson S, Fellman V, Ley D. Inflammation at birth and the insulin-like growth factor system in very preterm infants. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96(6):830–836. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hellström A, Engström E, Hård AL, et al. Postnatal serum insulin-like growth factor I deficiency is associated with retinopathy of prematurity and other complications of premature birth. Pediatrics. 2003;112(5):1016–1020. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.5.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawdon JM, Ward Platt MP, Aynsley-Green A. Patterns of metabolic adaptation for preterm and term infants in the first neonatal week. Arch Dis Child. 1992;67(4 Spec):357–365. doi: 10.1136/adc.67.4_spec_no.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen-Pupp I, Löfqvist C, Polberger S, et al. Influence of insulin-like growth factor I and nutrition during phases of postnatal growth in very preterm infants. Pediatr Res. 2011;69(5 Pt 1):448–453. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182115000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LeRoith D, Yakar S. Mechanisms of disease: metabolic effects of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor 1. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2007;3(3):302–310. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stigson L, Kistner A, Sigurdsson J, et al. Bone and fat mass in relation to postnatal levels of insulin-like growth factors in prematurely born children at 4.y of age. Pediatr Res. 2014;75(4):544–550. doi: 10.1038/pr.2014.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bach LA. Endothelial cells and the IGF system. J Mol Endocrinol. 2015;54(1):R1–R13. doi: 10.1530/JME-14-0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hellstrom A, Perruzzi C, Ju M, et al. Low IGF-I suppresses VEGF-survival signaling in retinal endothelial cells: direct correlation with clinical retinopathy of prematurity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(10):5804–5808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101113998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Paepe ME, Mao Q, Powell J, et al. Growth of pulmonary microvasculature in ventilated preterm infants. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(2):204–211. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200506-927OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wintermark P, Lechpammer M, Kosaras B, Jensen FE, Warfield SK. Brain Perfusion Is Increased at Term in the White Matter of Very Preterm Newborns and Newborns with Congenital Heart Disease: Does this Reflect Activated Angiogenesis? Neuropediatrics. 2015;46(5):344–351. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1563533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kistner A, Sigurdsson J, Niklasson A, Löfqvist C, Hall K, Hellström A. Neonatal IGF-1/IGFBP-1 axis and retinopathy of prematurity are associated with increased blood pressure in preterm children. Acta Paediatr. 2014;103(2):149–156. doi: 10.1111/apa.12478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gluckman PD, Harding JE. The physiology and pathophysiology of intrauterine growth retardation. Horm Res. 1997;48(Suppl 1):11–16. doi: 10.1159/000191257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu JP, Baker J, Perkins AS, Robertson EJ, Efstratiadis A. Mice carrying null mutations of the genes encoding insulin-like growth factor I (Igf-1) and type 1 IGF receptor (Igf1r) Cell. 1993;75(1):59–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baker J, Liu JP, Robertson EJ, Efstratiadis A. Role of insulin-like growth factors in embryonic and postnatal growth. Cell. 1993;75(1):73–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin CR, Brown YF, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Extremely Low Gestational Age Newborns Study Investigators. Nutritional practices and growth velocity in the first month of life in extremely premature infants. Pediatrics. 2009;124(2):649–657. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ehrenkranz RA, Dusick AM, Vohr BR, Wright LL, Wrage LA, Poole WK. Growth in the neonatal intensive care unit influences neuro-developmental and growth outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):1253–1261. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Torres-Aleman I. Toward a comprehensive neurobiology of IGF-I. Dev Neurobiol. 2010;70(5):384–396. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng CM, Reinhardt RR, Lee WH, Joncas G, Patel SC, Bondy CA. Insulin-like growth factor 1 regulates developing brain glucose metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(18):10236–10241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.170008497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joseph D’Ercole A, Ye P. Expanding the mind: insulin-like growth factor I and brain development. Endocrinology. 2008;149(12):5958–5962. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hansen-Pupp I, Hövel H, Hellström A, et al. Postnatal decrease in circulating insulin-like growth factor-I and low brain volumes in very preterm infants. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(4):1129–1135. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hansen-Pupp I, Hövel H, Löfqvist C, et al. Circulatory insulin-like growth factor-I and brain volumes in relation to neurodevelopmental outcome in very preterm infants. Pediatr Res. 2013;74(5):564–569. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blencowe H, Lawn JE, Vazquez T, Fielder A, Gilbert C. Preterm-associated visual impairment and estimates of retinopathy of prematurity at regional and global levels for 2010. Pediatr Res. 2013;74(Suppl 1):35–49. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Löfqvist C, Andersson E, Sigurdsson J, et al. Longitudinal postnatal weight and insulin-like growth factor I measurements in the prediction of retinopathy of prematurity. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124(12):1711–1718. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.12.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thébaud B. Angiogenesis in lung development, injury and repair: implications for chronic lung disease of prematurity. Neonatology. 2007;91(4):291–297. doi: 10.1159/000101344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Löfqvist C, Hellgren G, Niklasson A, Engström E, Ley D Hansen-Pupp I; WINROP Consortium. Low postnatal serum IGF-I levels are associated with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) Acta Paediatr. 2012;101(12):1211–1216. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2012.02826.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hellström A, Ley D, Hansen-Pupp I, et al. Insulin-like growth factor 1 has multisystem effects on foetal and preterm infant development. Acta Paediatr. 2016;105(6):576–586. doi: 10.1111/apa.13350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yakar S, Liu JL, Fernandez AM, et al. Liver-specific igf-1 gene deletion leads to muscle insulin insensitivity. Diabetes. 2001;50(5):1110–1118. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.5.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keswani SG, Balaji S, Katz AB, et al. Intraplacental gene therapy with Ad-IGF-1 corrects naturally occurring rabbit model of intra-uterine growth restriction. Hum Gene Ther. 2015;26(3):172–182. doi: 10.1089/hum.2014.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lassarre C, Hardouin S, Daffos F, Forestier F, Frankenne F, Binoux M. Serum insulin-like growth factors and insulin-like growth factor binding proteins in the human fetus. Relationships with growth in normal subjects and in subjects with intrauterine growth retardation. Pediatr Res. 1991;29(3):219–225. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199103000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bang P, Westgren M, Schwander J, Blum WF, Rosenfeld RG, Stangenberg M. Ontogeny of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1, -2, and -3: quantitative measurements by radioimmunoassay in human fetal serum. Pediatr Res. 1994;36(4):528–536. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199410000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hansen-Pupp I, Engström E, Niklasson A, et al. Fresh-frozen plasma as a source of exogenous insulin-like growth factor-I in the extremely preterm infant. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(2):477–482. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]