Abstract

Background

The genome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv has five copies of a cluster of genes known as the ESAT-6 loci. These clusters contain members of the CFP-10 (lhp) and ESAT-6 (esat-6) gene families (encoding secreted T-cell antigens that lack detectable secretion signals) as well as genes encoding secreted, cell-wall-associated subtilisin-like serine proteases, putative ABC transporters, ATP-binding proteins and other membrane-associated proteins. These membrane-associated and energy-providing proteins may function to secrete members of the ESAT-6 and CFP-10 protein families, and the proteases may be involved in processing the secreted peptide.

Results

Finished and unfinished genome sequencing data of 98 publicly available microbial genomes has been analyzed for the presence of orthologs of the ESAT-6 loci. The multiple duplicates of the ESAT-6 gene cluster found in the genome of M. tuberculosis H37Rv are also conserved in the genomes of other mycobacteria, for example M. tuberculosis CDC1551, M. tuberculosis 210, M. bovis, M. leprae, M. avium, and the avirulent strain M. smegmatis. Phylogenetic analyses of the resulting sequences have established the duplication order of the gene clusters and demonstrated that the gene cluster known as region 4 (Rv3444c-3450c) is ancestral. Region 4 is also the only region for which an ortholog could be found in the genomes of Corynebacterium diphtheriae and Streptomyces coelicolor.

Conclusions

Comparative genomic analysis revealed that the presence of the ESAT-6 gene cluster is a feature of some high-G+C Gram-positive bacteria. Multiple duplications of this cluster have occurred and are maintained only within the genomes of members of the genus Mycobacterium.

Background

Mycobacterium tuberculosis remains a serious threat to human health and in spite of significant investment in research on this organism, the mechanisms of its pathogenicity are still not clearly understood. One strategy used to determine these mechanisms is to compare the presence and absence of genes in different species (for example, virulent and avirulent) and extrapolate these differences to variation in phenotype. The genomes of M. tuberculosis H37Rv, M. tuberculosis H37Ra, M. bovis and the attenuated M. bovis BCG have been compared in different combinations using a variety of methods (subtractive genomic hybridization [1], bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) restriction profile analysis [2,3,4,5], BAC arrays [6], DNA microarrays [7] and Southern blotting [8]). This has identified a number of regions of difference (RD) between the various organisms.

One of these regions, designated the RD1 (region of difference 1) deletion region [1], is a 9,505 bp region absent in all M. bovis BCG strains. RD1 is commonly thought to be the primary deletion that occurred during the serial passage of M. bovis by Calmette and Guérin between 1908 and 1921, and is thus thought possibly to be responsible for the primary attenuation of M. bovis to M. bovis BCG [5,7]. Consequently, the genes contained in RD1 have been the object of a number of studies focusing on diagnosis of M. tuberculosis infection, the search for efficient vaccine candidates and virulence [9,10,11,12]. RD1 encompasses the genes Rv3871 to Rv3879c (annotation according to [13]), which include the genes for the 6 kDa early-secreted antigenic target ESAT-6 (esx or esat-6) and L45 homologous protein CFP-10 (lhp) [14,15]. The esat-6 and lhp genes are situated immediately adjacent to each other and encode potent T-cell antigens that are secreted but lack detectable secretion signals [16,17].

During the genome sequencing of M. tuberculosis H37Rv, Cole et al. [13] identified at least 11 additional genes encoding small proteins of approximately 100 amino acids that share sequence similarities with ESAT-6, and grouped them into the esat-6 gene family. In addition, they found several small genes with similarity to lhp (which encodes the protein CFP-10) that are also situated directly adjacent to the esat-6 family genes. Sequence analyses indicated that the lhp family members belong to and extend this esat-6 gene family. It was also found that the lhp gene is co-transcribed and thus forms part of an operon with esat-6 [15].

The genes encoding the originally annotated CFP-10 and ESAT-6 proteins within the RD1 deletion region lie in a cluster of 12 other genes (encompassing the deletion region), which seems to have been duplicated five times in the genome of M. tuberculosis. The duplicated gene clusters have been previously described as the ESAT-6 loci in an analysis of the proteome of M. tuberculosis [18]. An examination of the sets of genes in the clusters reveals that each of the clusters also contains (in addition to a copy of esat-6 and lhp), genes encoding putative ABC transporters (integral inner-membrane proteins), ATP-binding proteins, subtilisin-like membrane-anchored cell-wall-associated serine proteases (the mycosins [19]), and other amino-terminal membrane-associated proteins [18].

We have compared sequences to establish the relationship between the multiple copies of the ESAT-6 gene cluster. Our results show that the ESAT-6 gene cluster is of ancient origin, is present in, and restricted to, the genomes of other members of the high G+C Gram-positive bacteria such as Corynebacterium diphtheriae and Streptomyces coelicolor, and is duplicated multiple times in M. tuberculosis and other mycobacteria. We discuss the conservation of this gene cluster in the context of its possible functional importance and its use in diagnosis of mycobacterial infection.

Results

Individual gene families and genomic organization in M. tuberculosis

The five ESAT-6 gene clusters present in Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv were named region 1 (Rv3866-Rv3883c), 2 (Rv3884c-Rv3895c), 3 (Rv0282-Rv0292), 4 (Rv3444c-Rv3450c) and 5 (Rv1782-Rv1798), consistent with the arbitrary numbering system used previously to classify the five mycosin (subtilisin-like serine protease) genes identified from these regions [19]. Orthologs of the ESAT-6 gene clusters of M. tuberculosis H37Rv could be identified in the genomes of eight other strains and species belonging to the genus Mycobacterium, as well as in two species belonging to other genera (Table 1). Up to 12 different genes representing different gene families were identified in the five gene cluster regions and were designated families A to L according to their position in region 1 (Table 2).

Table 1.

Bacterial genome sequencing projects of species and strains containing ESAT-6 gene clusters

| Organism | Strain | Status | Last access date | Last update | Sequencing center(s) | References | |

| 1 | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | H37Rv | Completed | 5-Mar-2001 | 11-Jun-1998 | Sanger Centre/ Pasteur Institute | [13,20,47] |

| 2 | M. tuberculosis | CDC1551 (Oshkosh strain or CSU#93) | Completed | 5-Mar-2001 | 28-Jan-1999 | TIGR | [48] R.D. Fleischmann et al., unpublished data |

| 3 | M. tuberculosis | 210 | Partial sequencing project completed, no additional sequencing anticipated. | 21-May-2001 | 4-May-2001 | TIGR | [49] |

| 4 | M. bovis | AF2122/97 (spoligotype 9) | Shotgun in progress | 5-Mar-2001 | 29-Aug-2000 | Sanger Centre/ Pasteur Institute | [50] |

| 5 | M. bovis BCG | Pasteur 1173P2 | Unfinished | - | - | Pasteur Institute | [51] |

| 6 | M. leprae | TN | Completed | 7-Mar-2001 | 21-Feb-2001 | Sanger Centre/ Pasteur Institute | [25,52,53] |

| 7 | M. avium | 104 | Gap closure finished | 6-Mar-2001 | 22-Feb-2001 | TIGR | [49] |

| 8 | M. paratuberculosis | K10 | Unfinished (6.9 × coverage) | 6-Mar-2001 | 25-Feb-2001 | University of Minnesota | [29] |

| 9 | M. smegmatis | MC2 155 | Shotgun completed, assembly | 6-Mar-2001 | 22-Feb-2001 | TIGR | [49] |

| 10 | Corynebacterium diphtheriae | NCTC13129 | Finishing/gap closure | 5-Mar-2001 | 26-Feb-2001 | Sanger Centre | [54] |

| 11 | Streptomyces coelicolor | A3(2) | Cosmid sequencing | 5-Mar-2001 | 1-Mar-2001 | Sanger Centre | [55] |

Table 2.

Presence of genes in gene clusters of all available finished and unfinished genome sequences

| Presence and names of genes in each species | ||||||||||

| Gene family | Description | Protein size (in M. tb) | ESAT-6 cluster region | M. tuberculosis H37Rv | M. tuberculosis CDC1551 (CSU#93) | M. tuberculosis* 210 | M. bovis* AF2122/97 (spoligotype 9) | M. bovis* BCG Pasteur 1173P2 | ||

| A | ABC transporter family signature, 19-27% homology | 283 | 1 | Rv3866 | MT3980 | ND | MB851A | No sequence data | ||

| 276 | 2 | Rv3889c | MT4004 | MTB12A | MB727.3A (partly deleted #) | No sequence data | ||||

| 295 | 3 | Rv0289 | MT0302 | MTB203A | MB548A | No sequence data | ||||

| - | 4 | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | ||||

| 300 | 5 | Rv1794 | MT1843 | MTB196A | MB557A | No sequence data | ||||

| B | AAA+ class ATPases, CBXX/CFQX family, SpoVK, 1× ATP/GTP-binding site, 29-39% homology | 573 | 1 | Rv3868 | MT3981 | MTB44B | MB851B | No sequence data | ||

| 619 | 2 | Rv3884c | MT3999 | MTB12B | MB727.1B | No sequence data | ||||

| 631 | 3 | Rv0282 | MT0295 | MTB23B | MB672B | No sequence data | ||||

| - | 4 | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | ||||

| 610 | 5 | Rv1798 | MT1847 | MTB196B | MB542B | No sequence data | ||||

| C | Amino-terminal transmembrane protein, possible ATP/GTP-binding motif, 31-41% homology | 480 | 1 | Rv3869 | MT3982 | MTB44C | MB851C | No sequence data | ||

| 495 | 2 | Rv3895c | MT4011 | MTB136C | MB780.1C | No sequence data | ||||

| 538 | 3 | Rv0283 | MT0296 | MTB23C | MB672C | No sequence data | ||||

| 470 | 4 | Rv3450c | MT3556 | MTB45C | MB493.1C | No sequence data | ||||

| 506 | 5 | Rv1782 | MT1832 | MTB46C | MB771.1C | No sequence data | ||||

| D | DNA segregation ATPase, ftsK chromosome partitioning protein, SpoIIIE, yukA, 3× ATP/GTP-binding sites, 2× amino-terminal transmembrane protein, 28-39% homology | 747 + 591 | 1 | Rv3870+71 | MT3983+85 | MTB44Da+Db | MB851D | MB851D (partly deleted) | ||

| 1396 | 2 | Rv3894c | MT4010 | MTB3D | MB780.1D | No sequence data | ||||

| 1330 | 3 | Rv0284 | MT0297 | MTB23D | MB672D | No sequence data | ||||

| 1236 | 4 | Rv3447c | MT3553 | MTB45D | MB585.1D | No sequence data | ||||

| 435 + 932 | 5 | Rv1783+84 | MT1833 | MTB46Da+Db | MB771.1D | No sequence data | ||||

| E | PE, 18-90% homology | 99 | 1 | Rv3872 | MT3986 | MTB44E | MB851E | Deleted | ||

| 77 | 2 | Rv3893c | MT4008 | MTB3E | MB780.1E | No sequence data | ||||

| 102 | 3 | Rv0285 | MT0298 | MTB23E | MB389E | No sequence data | ||||

| - | 4 | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | ||||

| 99 & 99 | 5 | Rv1788 & 91 | MT1837 & 40 | MTB196Ea & Eb | MB771.0E & MB557E | No sequence data | ||||

| F | PPE, 19-88% homology | 368 | 1 | Rv3873 | MT3987 | MTB44F | MB851F | Deleted | ||

| 399 | 2 | Rv3892c | MT4007 | MTB3F | MB780.1F | No sequence data | ||||

| 513 | 3 | Rv0286 | MT0299 | MTB472F | MB528F | No sequence data | ||||

| - | 4 | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | ||||

| 365, 393 & 350 | 5 | Rv1787 & 89 & 90 | MT1836 & 38 & 39 | MTB196Fa & Fb & Fc | MB771.0Fa & Fb & MB557F | No sequence data | ||||

| G | lhp or CFP-10, also MTSA-10, grouped into ESAT-6 family, potent secreted T-cell antigens, 9-32% homology | 100 | 1 | Rv3874 | MT3988 | MTB44G | MB851G | Deleted | ||

| 107 | 2 | Rv3891c | MT4006 | MTB12G | MB727.3G | No sequence data | ||||

| 97 | 3 | Rv0287 | MT0300 | MTB472G | MB548G | No sequence data | ||||

| 125 | 4 | Rv3445c | MT3550 | MTB45G | MB585.0G | No sequence data | ||||

| 98 | 5 | Rv1792 (Stop) | MT1841 (Stop) | MTB196G (Stop) | MB557G | No sequence data | ||||

| H | ESAT-6 family, cfp7, L45 or l-esat, also Mtb9.9 family, potent secreted T-cell antigens, 15-27% homology | 95 | 1 | Rv3875 | MT3989 | MTB44H | MB851H † | Deleted | ||

| 95 | 2 | Rv3890c | MT4005 | MTB12H | MB727.3H | No sequence data | ||||

| 96 | 3 | Rv0288 | MT0301 | MTB203H | MB548H | No sequence data | ||||

| 100 | 4 | Rv3444c | MT3549 | MTB45H | MB585.0H | No sequence data | ||||

| 94 | 5 | Rv1793 | MT1842 | MTB196H | MB557H | No sequence data | ||||

| I | ATPases involved in chromosome partitioning, 1× ATP/GTP-binding motif, -33% homology- | 666 | 1 | Rv3876 | MT3990 | MTB60I | MB477I | Deleted | ||

| 341 | 2 | Rv3888c | MT4003 | MTB12I | Deleted # | No sequence data | ||||

| - | 3 | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | ||||

| - | 4 | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | ||||

| - | 5 | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | ||||

| J | Integral inner membrane protein, binding-protein-dependent transport systems inner membrane component signature, putative transporter protein, 19-27% homology | 511 | 1 | Rv3877 | MT3991 | MTB369J | MB477J | Deleted | ||

| 509 | 2 | Rv3887c | MT4002 | MTB12J | MB727.3J (partly deleted #) | No sequence data | ||||

| 472 | 3 | Rv0290 | MT0303 | MTB203J | MB548J | No sequence data | ||||

| 467 | 4 | Rv3448 | MT3554 | MTB45J | MB585.1J | No sequence data | ||||

| 503 | 5 | Rv1795 | MT1844 | MTB196J | MB506J | No sequence data | ||||

| K | Mycosins, subtilisin-like cell-wall associated serine proteases, 43-49% homology | 446 | 1 | Rv3883c | MT3998 | MTB12Ka | MB727.0K | No sequence data | ||

| 550 | 2 | Rv3886c | MT4001(Frame) | MTB12Kb | MB727.2K | No sequence data | ||||

| 461 | 3 | Rv0291 | MT0304 | MTB203K | MB548K | No sequence data | ||||

| 455 | 4 | Rv3449 | MT3555 | MTB45K | MB585.1K | No sequence data | ||||

| 585 | 5 | Rv1796 | MT1845 | MTB196K | MB506K | No sequence data | ||||

| L | 2× amino-terminal transmembrane protein, 16-27% homology | 462 | 1 | Rv3882c | MT3997 | MTB12La | MB727.0L | No sequence data | ||

| 537 | 2 | Rv3885c | MT4000 (Frame) | MTB12Lb | MB727.2L | No sequence data | ||||

| 331 | 3 | Rv0292 | MT0305 | MTB203L | MB694.0L | No sequence data | ||||

| - | 4 | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | ||||

| 406 | 5 | Rv1797 | MT1846 | MTB196L | MB542L | No sequence data | ||||

| Presence and names of genes in each species | ||||||||||

| Gene family | Description | Protein size (in M. tb) | ESAT-6 cluster region | M. leprae TN | M. avium* 104 | M. paratuberculosis K 10 | M. smegmatis* MC2 155 | C. diphtheriae* NCTC13129 | S. coelicolor A3 (2) | |

| A | ABC transporter family signature, 19-27% homology | 283 | 1 | ML0057(pseudo) | ND | ND | MS29A | ND | ND | |

| 276 | 2 | MLabc (pseudo)‡ | MA138A | MP3889c | ND | ND | ND | |||

| 295 | 3 | ML2530 | MA141A | MP0289 | MS32A | ND | ND | |||

| - | 4 | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | |||

| 300 | 5 | ML1540 | MA310A | MP1794 | ND | ND | ND | |||

| B | AAA+ class ATPases, CBXX/CFQX family, SpoVK, 1x ATP/GTP binding site, 29-39% homology | 573 | 1 | ML0055 | ND | ND | MS29B | ND | ND | |

| 619 | 2 | ML0039(pseudo) | MA177B | MP3884c | ND | ND | ND | |||

| 631 | 3 | ML2537 | MA78B | MP0282 | MS32B | ND | ND | |||

| - | 4 | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | |||

| 610 | 5 | ML1536 | MA310B | MP1798 | ND | ND | ND | |||

| C | Amino-terminal transmembrane protein, possible ATP/GTP- binding motif, 31-41% homology | 480 | 1 | ML0054 | ND | ND | MS29C | ND | ND | |

| 495 | 2 | Deleted | MA144C | MP3895c | ND | ND | ND | |||

| 538 | 3 | ML2536 | MA78C | MP0283 | MS32C | ND | ND | |||

| 470 | 4 | Deleted | MA94C | MP3450c | MS8C | CORDmem | SC3C3.07 | |||

| 506 | 5 | ML1544 | MA221C | MP1782 | ND | ND | ND | |||

| D | DNA segregation ATPase, ftsK chromosome partitioning protein, SpoIIIE, yukA, 3× ATP/GTP-binding sites 2 × amino-terminal transmembrane protein, 28-39% homology | 747+591 | 1 | ML0053+52 | ND | ND | MS29D (Stop$) | ND | ND | |

| 1396 | 2 | Deleted | MA144D | MP3894c | ND | ND | ND | |||

| 1330 | 3 | ML2535 | MA78D | MP0284 | MS32D | ND | ND | |||

| 1236 | 4 | Deleted | MA504D | MP3447c | MS8D | CORDyuk | SC3C3.20c | |||

| 435+932 | 5 | ML1543 | MA221D | MP1783 | ND | ND | ND | |||

| E | PE, 18-90% homology | 99 | 1 | Deleted | ND | ND | MS29E | ND | ND | |

| 77 | 2 | Deleted | MA138E | MP3893c | ND | ND | ND | |||

| 102 | 3 | ML2534 | MA78E | MP0285 | MS32E | ND | ND | |||

| - | 4 | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No | |||

| 99 & 99 | 5 | Deleted | MA310Ea & Eb | MP1788 & 91 | ND | ND | ND | |||

| F | PPE, 19-88% homology | 368 | 1 | ML0051 | ND | ND | MS29F | ND | ND | |

| 399 | 2 | Deleted | MA138F | MP3892c | ND | ND | ND | |||

| 513 | 3 | ML2533 (pseudo) | MA78F | MP0286 | MS32F | ND | ND | |||

| - | 4 | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | |||

| 365, 393 & 350 | 5 | Deleted | MA310Fa & Fb & Fc | MP1787 & 89 & 90 | ND | ND | ND | |||

| G | lhp or CFP-10, also MTSA-10, grouped ESAT-6 family, potent secreted T-cell antigens, 9-32% homology | 100 | 1 | ML0050 | ND | ND | MS29G | ND | SC3C3.10 and SC3C3.11(c) | |

| 107 | 2 | Deleted | MA138G | MP3891c § | ND | ND | ND | |||

| 97 | 3 | ML2532 | MA141G | MP0287 | MS32G | ND | ND | |||

| 125 | 4 | Deleted | MA319G | MP3445c | MS8G | CORDcfp10 | ND | |||

| 98 | 5 | MLcfp (pseudo)‡ | MA310G | MP1792 | ND | ND | ND | |||

| H | ESAT-6 family, cfp7, L45 or l-esat, also Mtb9.9 family, potent secreted T-cell antigens, 15-27% homology | 95 | 1 | ML0049 | ND | ND | MS29H | ND | SC3C3.10 and SC3C3.11¶ | |

| 95 | 2 | ML0034 (pseudo) | MA138H | MP3890c § | ND | ND | ND | |||

| 96 | 3 | ML2531 | MA141H | MP0288 | MS32H | ND | ND | |||

| 100 | 4 | ML0363 | MA319H | MP3444c | MS8H | CORDesat6 | ND | |||

| 94 | 5 | MLesat (pseudo)‡ | MA310H | MP1793 | ND | ND | ND | |||

| I | ATPases involved in chromosome partitioning, 1x ATP/GTP-binding motif, 33% homology | 666 | 1 | ML0048 | ND | ND | MS29I | ND | SC3C3.03c | |

| 341 | 2 | ML0035 (pseudo) | MA138I | MP3888c | ND | ND | ND | |||

| - | 3 | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | |||

| - | 4 | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | |||

| - | 5 | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | |||

| J | Integral inner membrane protein, binding-protein-dependent transport systems inner membrane component signature, putative transporter protein, 19-27% homology | 511 | 1 | ML0047 | ND | ND | MS29J | ND | ND | |

| 509 | 2 | ML0036 (pseudo) | MA138J | MP3887c | ND | ND | ND | |||

| 472 | 3 | ML2529 | MA141J | MP0290 | MS32J | ND | ND | |||

| 467 | 4 | Deleted | MA504J | MP3448 | MS8J | CORDtransporter | SC3C3.21 | |||

| 503 | 5 | ML1539 | MA310J | MP1795 | ND | ND | ND | |||

| K | Mycosins, subtilisin-like cell-wall associated serine proteases, 43-49% homology | 446 | 1 | ML0041 | ND | ND | MS65K | ND | ND | |

| 550 | 2 | ML0037 (pseudo) | MA177K | MP3886c | ND | ND | ND | |||

| 461 | 3 | ML2528 | MA141K | MP0291 | MS32K | ND | ND | |||

| 455 | 4 | Deleted | MA439K | MP3449 | MS8K | CORDsub | SC3C3.17c and SC3C3.08 | |||

| 585 | 5 | ML1538 | MA310K | MP1796 | ND | ND | ND | |||

| L | 2× amino-terminal transmembrane protein, 16-27% homology | 462 | 1 | ML0042 | ND | ND | MS65L | ND | ND | |

| 537 | 2 | ML0038 (pseudo) | MA177L | MP3885c | ND | ND | ND | |||

| 331 | 3 | ML2527 | MA81L | MP0292 | MS32L | ND | ND | |||

| - | 4 | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | No duplication | |||

| 406 | 5 | ML1537 | MA310L | MP1797 | ND | ND | ND | |||

| Other region-specific genes of known functions (not assigned to a family) | ||||||||||

| Region 5 (not present in M. smegmatis, C. diphtheriae and S. coelicolor) | Rv1785c | Probable member of the cytochrome P450 family (pseudogene in M. leprae) | ||||||||

| Rv1786 | Probable ferredoxin (pseudogene in M. leprae) | |||||||||

| Other region-specific genes of unknown functions (not assigned to a family) | ||||||||||

| Region 1(deleted in M. avium and M. paratuberculosis, not present in C. diphtheriae and S. coelicolor) | Rv3867 | Unknown, annotated as part of MT3980 (Rv3866) in M. tuberculosis CDC1551 sequence with a frameshift (functional in M. leprae) | ||||||||

| Rv3878 | Unknown, some similarity to PPE family, deleted with RD1 deletion region in M. bovis BCG (pseudogene in M. leprae) | |||||||||

| Rv3879c | Unknown, repetitive, highly proline-rich N-terminus, deleted with RD1 deletion region in M. bovis BCG (pseudogene in M. leprae) | |||||||||

| Rv3880c | Unknown (functional in M. leprae) | |||||||||

| Rv3881c | Unknown (pseudogene in M. leprae) | |||||||||

| Region 4 (not present in S. coelicolor) | Rv3446c | Unknown, may contain a possible ABC transporter signature (deleted in M. leprae) | ||||||||

*Names of genes of these organisms were given arbitrarily by the authors of this paper. †Gene not identified by BLAST, data obtained from [1], GenBank accession no. U34848 and AAC44033. ‡The gene is present in the sequence, but not annotated (name given arbitrarily by authors of this paper). §Genes identified by BLAST as well as data obtained from GenBank, accession no. AJ250015. ¶Orthologs in S. coelicolor are equally similar to family G and H. ND, Not detected - not necessarily absent from genome but possibly not detected because of unfinished sequencing process. No duplication, no duplication of this gene is present in this region. No sequence data, no sequence data is available for this organism, published deletion information is included ([1] and others). Deleted, deleted from the genome of this particular species or strain (# = deleted in only some strains of this species). Frame, frameshift. Stop, in-frame stop codon. Stop$, stop codon corresponds to stop codon in M. tuberculosis H37Rv, which splits gene into Rv3870 and Rv3871. Pseudo, confirmed pseudogene due to multiple frameshifts and stop codons.

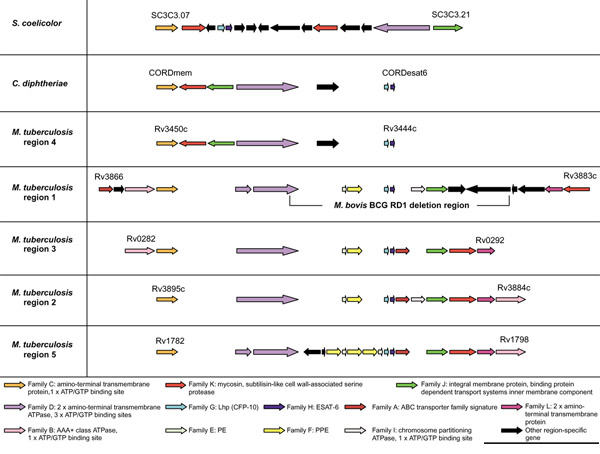

Figure 1 shows a schematic representation of the genomic organization of the gene families present in each of the five ESAT-6 cluster regions of M. tuberculosis. Annotations and descriptions of single genes in these regions can be found at [20]. Regions 1 and 2 are situated directly adjacent to each other in the genome and are transcribed in opposite directions. In both regions 1 and 5 the large gene belonging to family D (encoding the ATPase protein) has been disrupted by an insertion (Figure 1). This insertion has resulted in an in-frame stop codon, giving rise to two smaller genes (containing all the motifs of the larger homolog) located directly adjacent to each other. The gene positions of members of families C, D, G and H are maintained in all five regions (see Figure 1), whereas most of the families that are not present in region 4 seem to be more flexible with regard to their position within the gene clusters (families A, B, I and L). There are also genes present within some of the ESAT-6 gene clusters that do not have any homologs in the other clusters, suggesting subsequent insertions or deletions from the ancestral region (indicated by black arrows in Figure 1, see also Table 2).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the genomic organization of the genes present in the five ESAT-6 gene cluster regions of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv as well as the regions in C. diphtheriae and S. coelicolor. ORFs are represented as blocked arrows showing the direction of transcription, with the different colors reflecting the specific gene family and the length of the arrow reflecting the relative lengths of the genes. Annotations of M. tuberculosis H37Rv genes are according to Cole et al. [13]. Black arrows indicate unconserved genes present in these regions. Gaps between genes do not represent physical gaps between genes on the genome, but have been inserted to aid in indicating conservation among gene positions. Gene families were named arbitrarily according to their position in M. tuberculosis H37Rv region 1. The regions were named after the numbering system of Brown et al. [19] used arbitrarily for the five mycosin (subtilisin-like serine protease) genes identified from these regions (family K). M. tuberculosis regions are shown in order of suggested duplication events (see phylogenetic results) and not by numbering. The results of the analyses of the primary features of these genes and their corresponding proteins are included in a short summary at the bottom of the figure (see also Table 2).

The esat-6/lhp operon is not only present in the ESAT-6 gene clusters, but is distributed as six additional copies in the genome of M. tuberculosis (Figure 2). In four cases, the esat-6/lhp operon is flanked by ppe and pe genes (encoding proteins that have proline-proline-glutamic acid (PPE) and proline-glutamic acid (PE) motifs, respectively), indicating possible linked duplication between the esat-6/lhp operon and the pe/ppe gene pair.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the six additional esat-6/lhp operon duplications and the regions that surround them in the genome of M. tuberculosis H37Rv. ORFs are represented by blocked arrows indicating direction of transcription, with the different colors reflecting the specific gene family and the length of the arrow reflecting the relative lengths of the genes as in Figure 1. The esat-6 and lhp genes deleted in M. bovis RD07 and RD09 deletion regions [7] are indicated.

ESAT-6 gene cluster identification in other mycobacteria

Table 2 presents the results of the similarity searches and all available data for the 12 identified gene families present in the different regions. All the mycobacteria currently being sequenced contain multiple copies of these regions in their genomes. As these different copies are also found in the same respective genomic locations (corresponding flanking genes) in all the mycobacteria, it indicates that the duplication events took place prior to the divergence of the different species.

M. tuberculosis CDC1551, M. tuberculosis 210 and M. bovis

The genomes of the M. tuberculosis CDC1551 and 210 clinical strains as well as the genome of M. bovis contain all five of the ESAT-6 gene cluster regions present in the genome of M. tuberculosis H37Rv (sharing between 99 and 100% similarity to M. tuberculosis H37Rv at protein level). It is interesting to note, however, that two of the genes present in region 2 in CDC1551 (MT4000 and MT4001) contain frameshifts in their sequences, indicating that they and the rest of the region may no longer be functional in CDC1551. Part of region 2 (a 2,405 bp fragment containing Rv3887c, Rv3888c and Rv3889c) is also deleted in certain strains of M. bovis only, including the strain AF2122/97 that is currently being sequenced [21]. An in-frame stop codon found in Rv1792 (family G) is also present in the orthologs in CDC1551 (MT1841) and strain 210 (MTB196G), indicating that the mutation may have taken place before divergence of the three strains. Two of the H37Rv genes as well as the strain 210 family D genes (in regions 1 and 5) have acquired in-frame stop codons, resulting in two genes lying adjacent to each other, whereas the family D Rv1783 and Rv1784 orthologs in CDC1551 are still one intact gene (MT1833). The orthologs of this gene in M. bovis (MB771.1D), M. leprae (ML1543), M. avium (MA221D), and M. paratuberculosis(MP1783) are also intact, implying that the mutation in the H37Rv and strain 210 orthologs must have occurred after divergence of the three M. tuberculosis strains.

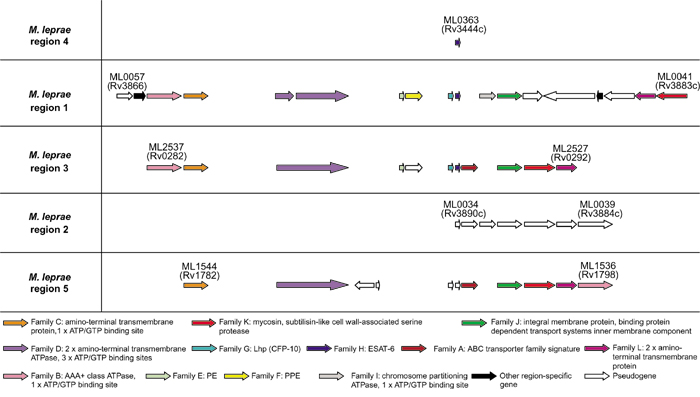

M. leprae

Figure 3 shows a schematic representation of the genomic organization of the respective gene families present in each of the five ESAT-6 gene clusters of M. leprae. The genome sequence of M. leprae contains functional copies of two of the five ESAT-6 gene cluster regions (regions 1 and 3, which have between 50 and 70% similarity to M. tuberculosis H37Rv at protein level). Most of the genes from region 2 are deleted, and all the remaining genes in this region have become pseudogenes as a result of extensive point mutations. This is in contrast to the genes from region 1 (which lies directly adjacent to region 2), which contains no pseudogenes. It is thus conceivable that these clusters should function as a unit, and that genes could become non-functional when part of the unit is disrupted. Furthermore, all the genes immediately flanking the putative functional regions, as well as five of the eight genes only present in one of the regions as depicted in Table 2 (the Rv1785c, Rv1786, Rv3878, Rv3879c and Rv3881c orthologs ML1542, ML1541, ML0046, ML0045 and ML0043), are probable pseudogenes, indicating that the genes present in the functional clusters are being maintained as a unit.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the genomic organization of the genes present in the five ESAT-6 gene cluster regions of Mycobacterium leprae. ORF's are represented as blocked arrows showing the direction of transcription, with the different colors reflecting the specific gene family and the length of the arrow reflecting the relative lengths of the genes as in Figure 1. Black arrows indicate unconserved genes present in these regions, while open arrows indicate pseudogenes. Annotations of M. leprae genes are according to Cole et al. [25].

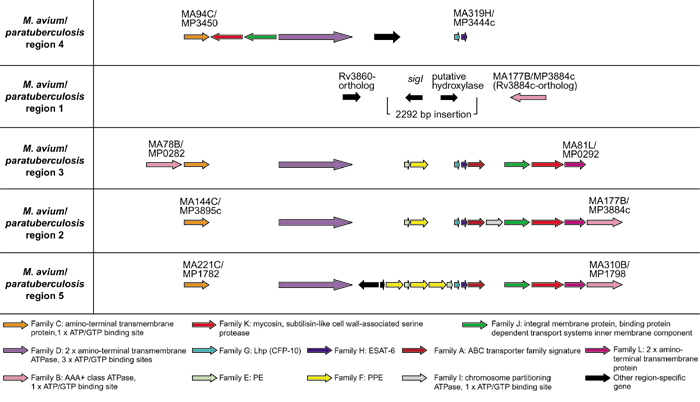

M. avium and M. paratuberculosis

The genomes of the M. avium strain 104 and the closely related species M. paratuberculosis (or M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis) has revealed four of the five ESAT-6 gene cluster regions (sharing between 65 and 75% similarity to M. tuberculosis H37Rv at protein level), with region 1 being absent in both species (Figure 4). Closer inspection of the gene sequence surrounding region 1 in both these species has revealed a deletion of the region containing region 1 and some upstream flanking genes (from the Rv3861 gene ortholog up to and including the Rv3883c ortholog). This deletion coincided with the insertion of a ± 2,292 bp sequence containing the genes for a putative hydroxylase (± 818 bp) and the sigI sigma factor (± 824 bp). The presence of this sequence in both genomes (99% DNA sequence identity) indicates that the insertion/deletion may have occurred before the divergence of the two species. The genes from the remaining ESAT-6 gene cluster regions that are present in M. avium and M. paratuberculosis contain no stop codons or frameshifts and thus appear to be functional.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the genomic organization of the genes present in the four ESAT-6 gene cluster regions of Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium paratuberculosis, as well as the flanking genes of the region 1 deletion. ORFs are represented as blocked arrows showing the direction of transcription, with the different colors reflecting the specific gene family and the length of the arrow reflecting the relative lengths of the genes as in Figure 1. Black arrows indicate unconserved genes present in these regions. M. avium and M. paratuberculosis genes were arbitrarily annotated by the authors of this paper.

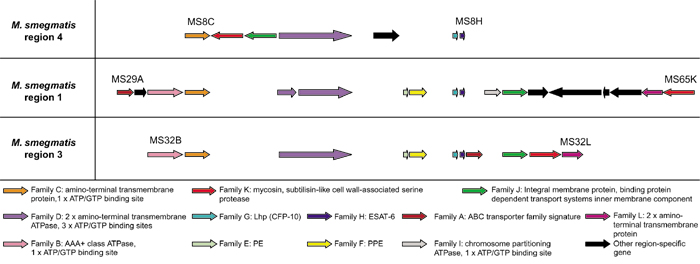

M. smegmatis

The genome sequence of the avirulent, fast-growing mycobacterial species M. smegmatis contains three of the five ESAT-6 gene cluster regions, namely regions 1, 3 and 4 (sharing between 60 and 75% similarity to M. tuberculosis H37Rv at protein level), with regions 2 and 5 being absent (Figure 5). No deletions, frameshifts or stop codons were identified in any of the genes present in the regions 1, 3 and 4 and therefore it is concluded that these regions are functional.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the genomic organization of the genes present in the three ESAT-6 gene cluster regions of Mycobacterium smegmatis. ORFs are represented as blocked arrows showing the direction of transcription, with the different colors reflecting the specific gene family and the length of the arrow reflecting the relative lengths of the genes as in Figure 1. Black arrows indicate unconserved genes present in these regions. M. smegmatis genes were arbitrarily annotated by the authors of this paper.

ESAT-6 gene cluster identification in bacteria other than the mycobacteria

Corynebacterium diphtheriae

The genome sequence of the closely related C. diphtheriae has revealed a copy of the region 4 ESAT-6 gene cluster (Figure 1, see Table 3 for percentage similarity between sequences), situated in the same genomic location as in the mycobacteria (indicated by the large stretch of flanking genes homologous to the genes flanking region 4 in M. tuberculosis H37Rv). All the genes present within this cluster appear to be fully functional, as no deletions, stop codons or frameshifts were identified. No duplications of the gene cluster could be detected in the genome of this organism.

Table 3.

Similarity of M. tuberculosis H37Rv region 4-encoded proteins to proteins encoded by the C. diphtheriae and S. coelicolor regions

| Percentage similarity | |||

| M. tuberculosis region 4 proteins | Family | ||

| C. diphtheriae | S. coelicolor | ||

| Rv3450c | C | 47% | 36% |

| Rv3447c | D | 53% | 57% |

| Rv3445c | G | 47% | 47 and 51%* |

| Rv3444c | H | 58% | 41 and 44%* |

| Rv3448 | J | 33% | 45% |

| Rv3449 | K | 49% | 45 and 47% |

* Orthologs in S. coelicolor are equally similar to families G and H.

Streptomyces coelicolor

The S. coelicolor genome has revealed distinct orthologs for four of the six most conserved genes from the ESAT-6 gene cluster regions located in close proximity to each other (Figure 1). These genes show the highest similarity to the corresponding orthologs in region 4 of M. tuberculosis (see Table 3 for percentage similarity between sequences). There is also a very distinct ortholog (SC3C3.03c) of the region 1 family I gene (Rv3876) in the S. coelicolor region. There is no homolog for this gene in region 4 of M. tuberculosis. A sequence-similarity search using the sequences of the other two proteins encoded in region 4, namely ESAT-6 (Rv3444c) and CFP-10 (Rv3445c), has also revealed some similarity to two small genes situated within the same region in the genome of S. coelicolor (Table 3, Figure 1). These genes (SC3C3.10 and SC3C3.11) encode small proteins (124 and 103 amino acids) of unknown function, are very similar to each other, and lie adjacent to each other, similar to the observation for the esat-6/lhp operon. The sequences of both these proteins also contain the motif W-X-G, a feature present in most of the ESAT-6 and CFP-10 proteins. The higher degree of similarity between the genes from region 4 of the mycobacteria (and C. diphtheriae) and those present in the region in S. coelicolor suggests that region 4 may be the ancestral region in the mycobacteria, although a number of differences between these regions do exist.

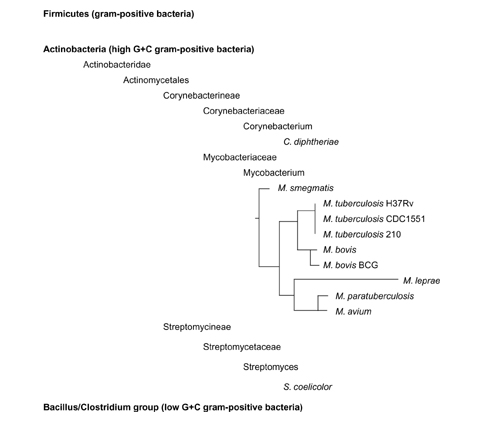

Taxonomy

It is evident from the taxonomy (Figure 6) of the different species of bacteria in which copies of the ESAT-6 gene clusters could be found, that the presence of these clusters appears to be a specific characteristic of the high G+C Gram-positive Actinobacteria, and that multiple copies thereof are only found in the mycobacteria. No copies of the clusters could be found in the completed genome sequenceof Bacillus subtilus and that of other related species, which also form part of the Firmicutes (Gram-positive bacteria), but fall under the Bacillus/Clostridium group (low G+C Gram-positive bacteria). No copies of these clusters could be found in the genomes of any other bacteria or organism outside of the Firmicutes and thus the ESAT-6 gene clusters appear to be unique to the Actinobacteria.

Figure 6.

Taxonomic position of the bacterial species that have the ESAT-6 gene clusters present in their genomes. This indicates that the ESAT-6 gene clusters seem to be a feature of only the high G+C Gram-positive bacteria (Actinobacteria) and that the presence of multiple copies of the gene clusters seems to be a characteristic only found in the mycobacteria. Phylogenetic relationships of members of the genus Mycobacterium indicated are based on 16S rRNA gene sequence information [56].

Phylogeny of the ESAT-6 gene cluster

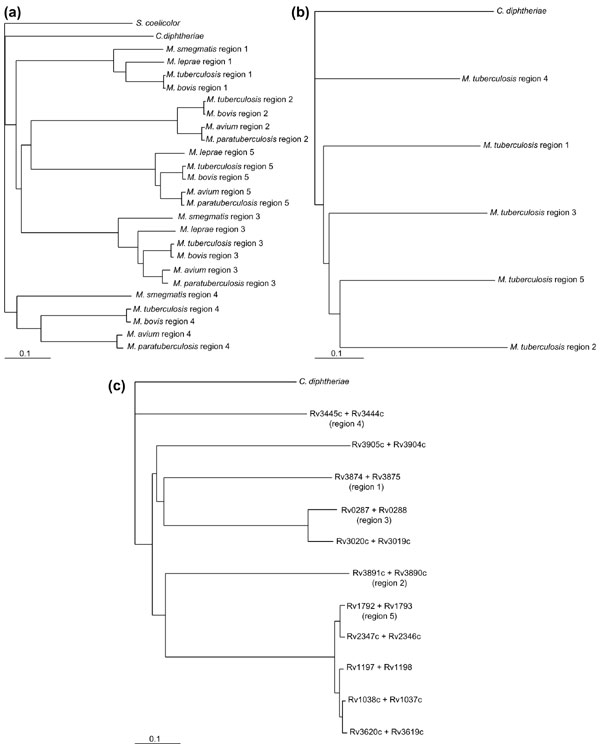

To calculate the phylogenetic relationships between the five duplicated ESAT-6 gene cluster regions in M. tuberculosis and to identify the ancestral region, detailed phylogenetic analyses were performed on each of the six protein families present in all five of these regions (families C, D, G, H, J and K). Figure 7a shows a neighbor-joining tree of the protein sequences of the ATP/GTP-binding protein family (family D) from the ESAT-6 gene clusters of mycobacteria and C. diphtheriae, with the protein ortholog from S. coelicolor as the outgroup. This tree is representative of all six trees that were drawn using the six families (data for the other trees are not shown). To confirm the results obtained with the S. coelicolor orthologs as outgroups, the same analyses were done using the C. diphtheriae orthologs as outgroups, with comparable results (data not shown). This tree topology was not due to systematic error, as trees drawn using the FITCH algorithm gave the same results (data not shown). To confirm the basic structure of the trees and to verify that this structure is not influenced by the choice of outgroup, unrooted trees without any outgroup were constructed using the KITSCH algorithm, once again with comparable results (data not shown). To further verify the relationships among these clusters, the conserved sequences of all six proteins from M. tuberculosis were combined into one protein sequence and the same analysis performed (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

Phylogenetic trees showing the relationships between the five duplicated gene cluster regions. (a) Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of all available protein sequences of the ATP/GTP-binding protein family (family D in Table 2) with the protein ortholog of Streptomyces coelicolor as the outgroup. This tree is representative of all the trees drawn using the six most conserved proteins in these regions as well as using the protein ortholog of Corynebacterium diphtheriae as the outgroup. (b) Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of all six conserved proteins from the M. tuberculosis gene clusters combined into one protein per region. The combined protein of C. diphtheriae was used as the outgroup. (c) Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of the ESAT-6 and CFP-10 protein families combined (family G and H), using the combined protein of C. diphtheriae as the outgroup.

To investigate whether the non-conserved protein families (those that are not present in region 4 of the mycobacteria, C. diphtheriae or S. coelicolor) show the same basic phylogenetic relationships as the conserved families (present in all five regions), an analysis was done on the AAA+ class ATPase family (family B). This family does not have a homolog in region 4 and there is also no C. diphtheriae or S. coelicolor ortholog to use as outgroup. The tree constructed from the data from this family clearly showed once again that regions 2 and 5, and region 1 and 3, respectively, are phylogenetically closer to each other (data not shown).

Neighbor joining, FITCH, KITSCH and concatenated sequence comparison analyses all supported a single phylogeny that indicated that region 4 seems to be the most ancient of the mycobacterial ESAT-6 gene cluster regions. Region 4 is also the closest region to the S. coelicolor and C. diphtheriae regions. The order of duplication seems to extend from region 4, through 1 and 3 to regions 2 and 5. The phylogenetic relationships between corresponding clusters in the different mycobacteria are maintained throughout the different protein-family trees, and agree with the proposed phylogenetic order (or taxonomic position) of the mycobacterial species according to 16S rRNA data (see Figure 6).

As the genome of M. tuberculosis contains 11 copies of the esat-6/lhp gene pair that appears to be duplicated together, phylogenetic trees were constructed using the ESAT-6 or CFP-10 proteins separately (data not shown), or in combination as one ESAT-6/CFP-10 protein (Figure 7c). Using the combined C. diphtheriae ESAT-6/CFP-10 ortholog protein as outgroup, the same organization of duplication events was obtained with regions 1, 3, 2 and lastly 5 being duplicated from the ancient region 4. The other copies of the esat-6/lhp operon pair that are present in the M. tuberculosis genome sequence, but are not part of the ESAT-6 gene cluster regions, seem to have arisen from singular duplication events originating from different cluster regions. It is interesting to note that esat-6 and lhp from region 5 seem to be highly prone to duplication, as there are four additional copies of these two genes present in the genome, compared to just one additional copy originating from region 4 and region 3, respectively. These four gene duplicates of esat-6 and lhp from region 5 are also nearly identical (93-100% similarity at protein level), indicating their recent duplication.

Discussion

It was recently estimated in an in silico analysis of the genome sequence of M. tuberculosis H37Rv, that 52% of the proteome has been derived from gene duplication events [18]. One such involves the formation of multiple copies of the genes for the secreted T-cell antigens ESAT-6 and CFP-10 [14,16,17] together with a number of associated genes. A total of twelve gene families were identified in five regions (which were termed the ESAT-6 loci).

Phylogenetic analyses of the protein sequences of the six most conserved gene families, present within the five regions, predict that region 4 (Rv3444c to Rv3450c) is the ancestral region. Region 4 also contains the least number of proteins (only 6 compared to the 12 of region 1 (Rv3866-3883c) and region 2 (Rv3884c-3895c)), and does not contain the genes for PE and PPE, which may have been inserted into this region after the first duplication. Phylogenetic analyses using different methods and protein family data also suggests that subsequent duplications took place in the following order: region 1 (Rv3866-3883c) → 3 (Rv0282-0292) → 2 (Rv3884c-3895c) → 5 (Rv1782-1798). Furthermore, these analyses support the taxonomic order observed for the mycobacteria, with M. smegmatis being taxonomically the farthest removed from M. tuberculosis. The presence of a copy of region 4 and its flanking genes in C. diphtheriae strengthens the taxonomic data that implies that the corynebacteria and mycobacteria have a common ancestor. It appears that C. diphtheriae diverged from the mycobacteria before the multiple duplications of the ESAT-6 gene cluster, as only one copy of this cluster could be identified in the genome of this organism.

The loss of region 1 from the genomes of the species M. avium and M. paratuberculosis (belonging to the M. avium complex) is confirmed by clinical data showing that patients seronegative for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and infected with mycobacteria belonging to the M. avium complex do not respond to ESAT-6 from region 1, but do recognize purified protein derivative (PPD) and M. avium sensitins [22]. The genes for ESAT-6 and CFP-10 (esat-6 and lhp) in region 1 are also not found in M. bovis BCG and have thus been the focus of recent research because of their application as diagnostic markers to differentiate between BCG vaccination and M. tuberculosis, M. bovis or M. avium infection (see for example [17,23]). In this study we have found several copies of the ESAT-6 and CFP-10 genes (with differing degrees of similarity) in the genomes of different mycobacteria (80% and 71% protein sequence similarity for ESAT-6 and CFP-10 respectively from region 1 in avirulent M. smegmatis), as well as orthologs in species outside the mycobacteria; care should therefore be taken when using these proteins for diagnostic purposes. It will be important to look at the protein sequence similarity between the copies of ESAT-6 and CFP-10 of different virulent and environmental mycobacterial species before a member of these immunodominant protein families can be chosen as a definite marker of M. tuberculosis infection. Studies to determine the production of interferon-γ in response to exposure to ESAT-6 and CFP-10 from environmental mycobacteria (for example M. smegmatis) by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from infected patients have not been done. Until these results are available, indicating that the T-cell responses against these proteins are not comparable to those against the M. tuberculosis proteins, care should be taken with claims regarding the potential diagnostic value of these antigens.

Most of the sequences of the genes belonging to the ESAT-6 gene cluster regions contain no stop codons or frameshifts and thus appear to be functional. This is significant when placed in the context of a bacterium such as M. leprae, as it is hypothesized that the genome of M. leprae may contain the minimal gene set required by a pathogenic mycobacterium [5,24,25] and that the activities of some functional genes once present in the genome of M. leprae have been silenced (they became pseudogenes through multiple stop codon mutations and frameshifts) because they are no longer needed for the bacterium's intracellular survival [13]. It appears that M. leprae contains at least two functional copies of the ESAT-6 gene cluster in its genome (regions 1 and 3). The M. leprae ESAT-6 copy from region 1 (the L45-antigen or L-ESAT antigen from clone L45) was shown to be strongly reactive to sera from leprosy patients [26], providing experimental evidence that at least one of the cluster regions is functional in M. leprae.

As most of the genes present within the ESAT-6 gene cluster regions encode proteins that are predicted to be associated with transport and energy-providing systems, we hypothesize that these proteins may be involved in the secretion of a substrate across the mycobacterial cell wall. It is well known that the T-cell antigens ESAT-6 and CFP-10 are found in short-term culture filtrates (ST-CF) of M. tuberculosis, although the mechanism of secretion is unknown, as these proteins do not possess any of the usual Sec-dependent secretion signals [14,15,16]. It is therefore possible that the genes in the ESAT-6 gene cluster regions act together to provide a system for the secretion of ESAT-6 and CFP-10. There is evidence for the processing of the TB10.4 protein (the ESAT-6 family member from region 3) to a lower molecular weight product [27], suggesting a possible role for the cell-wall-associated mycosin proteases [19] in the suggested transport system. Most of region 1 is situated in the RD1 deletion region of M. bovis BCG, possibly explaining the absence of expression of the mycosin-1 gene (Rv3883c) in BCG [19].

The hypothesis that an interdependent functional relationship exists between the proteins encoded in these regions is further supported by the M. leprae sequence data, which shows that deletions of parts of the ESAT-6 gene cluster region 2 apparently caused the remaining genes in the region to become pseudogenes. Furthermore, Wards and co-workers [12] produced an M. bovis knockout mutant of the ATPase gene Rv3871 (family D) in the ESAT-6 gene cluster region 1, resulting in a strain that did not sensitize guinea pigs to an ESAT-6 skin test. These results indicate a close relationship between the genes contained within these regions.

Wards et al. [12] showed that an esat-6/lfp knockout mutant of M. bovis was less virulent than its parent if gross pathology, histopathology and mycobacterial culture from tissues were taken into account. These results, combined with the fact that multiple copies of the ESAT-6 gene clusters are found in all the mycobacteria, clearly indicate that they form an important part of the mycobacterial genome. The presence of multiple duplications of the ESAT-6 gene cluster regions in the mycobacteria may be a significant difference between the members of this genus and other high G+C Gram-positives. Although the function of this cluster is presently unknown, there is sufficient evidence to indicate that it is of crucial importance to the mycobacteria and needs to be investigated further.

Materials and methods

Genome sequence data and analyses

Annotations and descriptions of individual genes as well as gene and protein sequences of individual organisms were obtained from the publicly available finished and unfinished genome sequence databases listed in Table 1. Preliminary sequence data for M. tuberculosis 210, M. avium 104 and M. smegmatis MC2 155 was obtained from The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) website [28]. Preliminary sequence data for M. paratuberculosis K10 was obtained from the University of Minnesota M. paratuberculosis website [29]. Preliminary sequence data for M. bovis AF2122/97(spoligotype 9), C. diphtheriae NCTC13129 and S. coelicolor A3 (2), was obtained from the Sanger Centre website [30]. All gene and protein sequences were subjected to analysis with the following programs to confirm annotation and to look for additional information: SignalP V2.0.b2 [31,32], ClustalW WWW server at the European Bioinformatics Institute [33,34], TMHMM v0.1 [35,36], MOTIF [37] and BLASTP [38,39]. No data, progress report or BLAST search function is available for the genome sequencing of M. bovis BCG Pasteur 1173P2 at the Pasteur Institute, but information concerning genome deletions was obtained from published data [1,2,3,5,6,7] and from the Pasteur Institute website [40].

Analyses of similar gene clusters

BLAST similarity searches [38], using the BLAST 2.0 program with tblastn and the BLOSUM-62 weight matrix, were used to identify stretches of DNA containing putative ORFs homologous to the genes found in the M. tuberculosis ESAT-6 gene cluster regions from finished and unfinished genome sequences available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website [41]. A total of 98 finished and unfinished genome sequences (35 from Gram-positive species) were used in the analysis, as summarized in Table 4. Where applicable, BLAST servers in database search services of individual sequencing centers were also used for protein identification. The Sanger Centre and The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) use the program WU-BLAST version 2.0 [42], while the University of Minnesota uses BLASTN with supplied defaults [43]. Sequences were only admitted to analysis when found to be part of one of the five gene clusters. In other words, no single homologous genes in the mycobacteria or other organisms (for example B. subtilis) that did not form part of a similar gene cluster were considered for the analyses, to exclude any potential unassociated similarity that could lead to false positives.

Table 4.

Publicly available finished and unfinished genome sequence databases used in this study

| Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans | Escherichia coli O157:H7 EDL933 | Rhodobacter sphaeroides |

| Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans | *Enterococcus faecalis | Salmonella dublin |

| Aquifex aeolicus | Geobacter sulfurreducens | Salmonella enteritidis |

| *Bacillus anthracis | Haemophilus ducreyi 35000HP | Salmonella paratyphi |

| *Bacillus halodurans | Haemophilus influenzae Rd | Salmonella typhi |

| *Bacillus subtilis | Helicobacter pylori 26695 | Salmonella typhimurium LT2 |

| *Bacillus stearothermophilus | Helicobacter pylori J99 | Shewanella putrefaciens |

| Bordetella bronchiseptica | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Sinorhizobium meliloti |

| Bordetella parapertussis | *Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis | *Staphylococcus aureus COL |

| Bordetella pertussis | Legionella pneumophila | *Staphylococcus aureus MRSA |

| Borrelia burgdorferi | *Listeria monocytogenes | *Staphylococcus aureus MSSA |

| Brucella melitensis biovar Suis | Mesorhizobium loti | *Staphylococcus aureus Mu50 |

| Buchnera sp. APS | Methylococcus capsulatus | *Staphylococcus aureus N315 |

| Burkholderia mallei | *Mycobacterium avium | *Staphylococcus aureus NCTC 8325 |

| Burkholderia pseudomallei | *Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis | *Staphylococcus epidermidis |

| Campylobacter jejuni NCTC 11168 | *Mycobacterium bovis | *Streptococcus equi |

| Carboxydothermus hydrogenoformans | *Mycobacterium leprae | *Streptococcus gordonii |

| Caulobacter crescentus | *Mycobacterium smegmatis | *Streptococcus mutans |

| Chlamydia muridarum | *Mycobacterium tuberculosis 210 | *Streptococcus pneumoniae |

| Chlamydia pneumoniae | *Mycobacterium tuberculosis CDC1551 | *Streptococcus pyogenes |

| Chlamydia trachomatis D/UW-3/CX | *Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv | |

| Chlamydophila pneumoniae AR39 | *Mycoplasma genitalium G37 | *Streptococcus pyogenes Manfredo |

| Chlamydophila psittaci | *Mycoplasma pneumoniae M129 | *Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) |

| Chlorobium tepidum | Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Synechocystis PCC6803 |

| *Clostridium acetobutylicum | Neisseria meningitidis MC58 | Thermotoga maritima |

| *Clostridium difficile | Neisseria meningitidis Z2491 | Treponema denticola |

| *Corynebacterium diphtheriae | Pasteurella multocida PM70 | Treponema pallidum |

| Coxiella burnetii | Porphyromonas gingivalis W83 | *Ureaplasma urealyticum |

| Dehalococcoides ethenogenes | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Vibrio cholerae |

| Desulfovibrio vulgaris | Pseudomonas putida KT2440 | Wolbachia |

| Deinococcus radiodurans | Pseudomonas putida PRS1 | Xylella fastidiosa |

| Escherichia coli K-12 MG1655 | Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato | Yersinia enterocolitica |

| Escherichia coli O157:H7 | Rickettsia prowazekii | Yersinia pestis |

Finished genome sequences are indicated in bold, * indicates Gram-positive species.

Contig sequences corresponding to the gene clusters were obtained from their respective genome databases and used in further analyses. The Genetics Computer Group (Wisconsin Package Version 10.0, Genetics Computer Group (GCG), Madison, Wisconsin) program FRAMESEARCH was used to obtain whole sequence ORFs from the contigs. These ORFs were translated to protein sequences with the program TRANSLATE (also from GCG). All multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic analyses were conducted on the protein level with these translated protein sequences.

Multiple sequence alignments

Multiple sequence alignments were performed on separate gene families belonging to the different clusters using ClustalW 1.5 [33] with the default parameters. The alignments were manually checked for errors and refined where appropriate. Multiple sequence alignments were also manually edited in some analyses during which unaligned regions (inserts) were removed (resulting in so-called edited alignments).

Phylogenetic trees

Bootstrapping resampling of the data sets were performed on the edited alignments, which generated 100 randomly chosen subsets of the multiple sequence alignment. Pairwise distances were determined with PROTDIST using the Dayhoff PAM matrix and neighbor-joining phylogenetic trees were calculated using NEIGHBOR (PHYLIP 3.5, [44]). In the case of each family of proteins, the C. diphtheriae sequence was first used as the outgroup after which the S. coelicolor sequence was used. Further phylogenetic analyses were performed using the programs FITCH and KITSCH with and without the outgroups respectively. A majority rule and strict consensus tree of all bootstrapped sequences were obtained using CONSENSE. The same analyses as described above were performed on a combined protein consisting of the edited aligned sequences of all six conserved proteins in these gene clusters as well as a combined protein constructed from the edited aligned sequences of all available ESAT-6 and CFP-10 family members. Finally, to confirm the results obtained with the single proteins, an analysis was performed with whole, unedited aligned sequences of the six most conserved proteins, using the program Paup 4.0b4a [45], during which negative branches were collapsed and 1,000 subsets were generated for bootstrapping resampling of the data. The consensus trees of all the above were drawn using the program Treeview 1.5 [46].

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Rob Warren for continued advice, support, and critical reading of the manuscript. Sequencing of M. paratuberculosis was accomplished with support from USDA and Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station; sequencing of M. avium 104 and M. smegmatis MC2 155 at TIGR with support from the NIAID, sequencing of M. bovis AF2122/97(spoligotype 9) with support from MAFF/Beowulf Genomics, C. diphtheriae NCTC13129 with support from Beowulf Genomics and S. coelicolor A3(2) with support from BBSRC/Beowulf Genomics. This work is dedicated to the memory of Albert Beyers.

References

- Mahairas GG, Sabo PJ, Hickey MJ, Singh DC, Stover CK. Molecular analysis of genetic differences between Mycobacterium bovis BCG and virulent M. bovis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1274–1282. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1274-1282.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipp WJ, Nair S, Guglielmi G, Lagranderie M, Gicquel B, Cole ST. Physical mapping of Mycobacterium bovis BCG pasteur reveals differences from the genome map of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv and from M. bovis. Microbiology. 1996;142:3135–3145. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-11-3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosch R, Gordon SV, Billault A, Garnier T, Eiglmeier K, Soravito C, Barrell BG, Cole ST. Use of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv bacterial artificial chromosome library for genome mapping, sequencing, and comparative genomics. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2221–2229. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2221-2229.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosch R, Philipp WJ, Stavropoulos E, Colston MJ, Cole ST, Gordon SV. Genomic analysis reveals variation between Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv and the attenuated M. tuberculosis H37Ra strain. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5768–5774. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5768-5774.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosch R, Gordon SV, Buchrieser C, Pym AS, Garnier T, Cole ST. Comparative genomics uncovers large tandem chromosomal duplications in Mycobacterium bovis BCG Pasteur. Yeast. 2000;17:111–123. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(20000630)17:2<111::AID-YEA17>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon SV, Brosch R, Billault A, Garnier T, Eiglmeier K, Cole ST. Identification of variable regions in the genomes of tubercle bacilli using bacterial artificial chromosome arrays. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:643–655. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behr MA, Wilson MA, Gill WP, Salamon H, Schoolnik GK, Rane S, Small PM. Comparative genomics of BCG vaccines by whole-genome DNA microarray. Science. 1999;284:1520–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5419.1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zumarraga M, Bigi F, Alito A, Romano MI, Cataldi A. A 12.7 kb fragment of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome is not present in Mycobacterium bovis. Microbiology. 1999;145:893–897. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-4-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad S, Amoudy HA, Thole JE, Young DB, Mustafa AS. Identification of a novel protein antigen encoded by a Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific RD1 region gene. Scand J Immunol. 1999;49:515–522. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1999.00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt L, Elhay M, Rosenkrands I, Lindblad EB, Andersen P. ESAT-6 subunit vaccination against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:791–795. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.2.791-795.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arend SM, Geluk A, van Meijgaarden KE, van Dissel JT, Theisen M, Andersen P, Ottenhoff TH. Antigenic equivalence of human T-cell responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific RD1-encoded protein antigens ESAT-6 and culture filtrate protein 10 and to mixtures of synthetic peptides. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3314–3321. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3314-3321.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wards BJ, de Lisle GW, Collins DM. An esat6 knockout mutant of Mycobacterium bovis produced by homologous recombination will contribute to the development of a live tuberculosis vaccine. Tuber Lung Dis. 2000;80:185–189. doi: 10.1054/tuld.2000.0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon SV, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry CE, III, et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen P, Andersen AB, Sørensen AL, Nagai S. Recall of long-lived immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. J Immunol. 1995;154:3359–3372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthet FX, Rasmussen PB, Rosenkrands I, Andersen P, Gicquel B. A Mycobacterium tuberculosis operon encoding ESAT-6 and a novel low- molecular-mass culture filtrate protein (CFP-10). Microbiology. 1998;144:3195–3203. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-11-3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen AL, Nagai S, Houen G, Andersen P, Andersen AB. Purification and characterization of a low-molecular-mass T-cell antigen secreted by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1710–1717. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1710-1717.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Pinxteren LA, Ravn P, Agger EM, Pollock J, Andersen P. Diagnosis of tuberculosis based on the two specific antigens ESAT-6 and CFP10. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000;7:155–160. doi: 10.1128/cdli.7.2.155-160.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekaia F, Gordon SV, Garnier T, Brosch R, Barrell BG, Cole ST. Analysis of the proteome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in silico. Tuber Lung Dis. 1999;79:329–342. doi: 10.1054/tuld.1999.0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GD, Dave JA, Gey van Pittius NC, Stevens L, Ehlers MR, Beyers AD. The mycosins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv: a family of subtilisin-like serine proteases. Gene. 2000;254:147–155. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00277-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuberculist http://genolist.pasteur.fr/TubercuList/

- Rauzier J, Gormley E, Gutierrez MC, Kassa-Kelembho E, Sandall LJ, Dupont C, Gicquel B, Murray A. A novel polymorphic genetic locus in members of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Microbiology. 1999;145:1695–1701. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-7-1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lein AD, von Reyn CF, Ravn P, Horsburgh CR, Jr, Alexander LN, Andersen P. Cellular immune responses to ESAT-6 discriminate between patients with pulmonary disease due to Mycobacterium avium complex and those with pulmonary disease due to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:606–609. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.4.606-609.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vordermeier HM, Cockle PJ, Whelan AO, Rhodes S, Hewinson RG. Toward the development of diagnostic assays to discriminate between Mycobacterium bovis Infection and Bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccination in cattle. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(Suppl 3):S291–S298. doi: 10.1086/313877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wixon J. Genomes 2000 International Conference on Microbial and Model Genomes. Yeast. 2000;17:124–133. [Google Scholar]

- Cole ST, Eiglmeier K, Parkhill J, James KD, Thomson NR, Wheeler PR, Honore N, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, et al. Massive gene decay in the leprosy bacillus. Nature. 2001;409:1007–1011. doi: 10.1038/35059006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathish M, Esser RE, Thole JE, Clark-Curtiss JE. Identification and characterization of antigenic determinants of Mycobacterium leprae that react with antibodies in sera of leprosy patients. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1327–1336. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.5.1327-1336.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skjøt RL, Oettinger T, Rosenkrands I, Ravn P, Brock I, Jacobsen S, Andersen P. Comparative evaluation of low-molecular-mass proteins from Mycobacterium tuberculosis identifies members of the ESAT-6 family as immunodominant T-cell antigens. Infect Immun. 2000;68:214–220. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.214-220.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Institute for Genomic Research http://www.tigr.org

- University of Minnesota M. paratuberculosis http://www.cbc.umn.edu/ResearchProjects/AGAC/Mptb/Mptbhome.html

- Sanger Centre http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/

- Nielsen H, Engelbrecht J, Brunak S, von Heijne G. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 1997;10:1–6. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SignalP V2.0.b2 http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP-2.0/#submission

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ClustalW WWW server at the European Bioinformatics Institute http://www2.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/

- Sonnhammer EL, von Heijne G, Krogh A. A hidden Markov model for predicting transmembrane helices in protein sequences. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol. 1998;6:175–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TMHMM v0.2 http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-2.0/

- MOTIF http://www.motif.genome.ad.jp/

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLASTP http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/

- Pasteur Institute http://www.pasteur.fr/recherche/unites/Lgmb/Deletion.html

- NCBI BLAST Server http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Microb_blast/unfinishedgenome.html

- WU-BLAST version 2.0 http://blast.wustl.edu/

- University of Minnesota BLAST Server http://www.cbc.umn.edu/cgi-bin/blasts/AGAC.restrict/blastn.cgi

- Felsenstein J. PHYLIP - Phylogeny Inference Package (Version 3.2). Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL. PAUP* Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (* and Other Methods) Version 4 1998, Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts.

- Page RD. TreeView: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996;12:357–358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Sanger Centre : M. tuberculosis Genome Project http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/M_tuberculosis/

- TIGR Mycobacterium tuberculosis CDC1551 Information http://www.tigr.org/tigr-scripts/CMR2/GenomePage3.spl?database=gmt

- TIGR BLAST Search Engine for Unfinished Microbial Genomes http://www.tigr.org/cgi-bin/BlastSearch/blast.cgi?

- The Sanger Centre : M. bovis Genome Project http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/M_bovis/

- Pasteur Institute Mycogenomics http://www.pasteur.fr/recherche/unites/Lgmb/mycogenomics.html

- The Sanger Centre : Mycobacterium leprae genome project http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/M_leprae/

- Pasteur Institute Leproma http://genolist.pasteur.fr/Leproma

- The Sanger Centre : C. diphtheriae Genome Project http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/C_diphtheriae/

- The Sanger Centre : S. coelicolor Genome Project http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/S_coelicolor/

- Shinnick TM, Good RC. Mycobacterial taxonomy. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;13:884–901. doi: 10.1007/BF02111489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]