Abstract

The aim of the current study was to identify gene signatures during the early proliferation stage of wound repair and the effect of TGF-β on fibroblasts and reveal their potential mechanisms. The gene expression profiles of GSE79621 and GSE27165 were obtained from GEO database. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using Morpheus and co-expressed DEGs were selected using Venn Diagram. Gene ontology (GO) function and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs were performed using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) online tool. Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks of the DEGs were constructed using Cytoscape software. PPI interaction network was divided into subnetworks using the MCODE algorithm and the function of the top one module was analyzed using DAVID. The results revealed that upregulated DEGs were significantly enriched in biological process, including the Arp2/3 complex-mediated actin nucleation, positive regulation of hyaluronan cable assembly, purine nucleobase biosynthetic process, de novo inosine monophosphate biosynthetic process, positive regulation of epithelial cell proliferation, whereas the downregulated DEGs were enriched in the regulation of blood pressure, negative regulation of cell proliferation, ossification, negative regulation of gene expression and type I interferon signaling pathway. KEGG pathway analysis showed that the upregulated DEGs were enriched in shigellosis, pathogenic Escherichia coli infection, the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway, Ras signaling pathway and bacterial invasion of epithelial cells. The downregulated DEGs were enriched in systemic lupus erythematosus, lysosome, arachidonic acid metabolism, thyroid cancer and allograft rejection. The top 10 hub genes were identified from the PPI network. The top module analysis revealed that the included genes were involved in ion channel, neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway, purine metabolism and intestinal immune network for IgA production pathway. The functional analysis revealed that TGF-β may promote fibroblast migration and proliferation and defend against microorganisms at the early proliferation stage of wound repair. Furthermore, these results may provide references for chronic wound repair.

Keywords: bioinformatics analysis, fibroblasts, transforming growth factor-β, wound repair

Introduction

Fibroblasts are widely distributed throughout the mesenchyme where they synthesize extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins that form a structural framework to support tissue architecture and function in steady-state conditions (1). Skin wound repair is a complex process that involves inflammation, proliferation and a remolding phase. At the early proliferation stage, fibroblast migration to the wound site is important for the formation of provisional ECM, such as collagen and fibronectin, in which the respective cell migration and organization takes place in successful repair (2–22).

Various signaling pathways, the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)/SMAD pathway in particular, have been investigated in the process of wound healing; however, the mechanisms of these pathways remain to be elucidated. TGF-β, a multifunctional cytokine secreted by macrophages, and its effect on wounds is controversial (23,24). TGF-β may stimulate collagen production in dermal fibroblasts by fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition (25), the excess amount of TGF-β increases collagen deposition, resulting in a keloid (26). TGF-β that is produced during inflammatory phase by macrophages is an important mediator of fibroblast activation and tissue repair (27). Although the effect of TGF-β on wounds has been previously identified, the complete underlying effect of TGF-β on fibroblasts at the early proliferation phase of wound repair remain poorly understood.

Microarray technology has been used to obtain information on the genetic alteration that occurs during many diseases (28–30). The current study used bioinformatics to identify the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) of fibroblasts treated with TGF-β for 24 h. Then, the gene ontology (GO) and pathway enrichment were analyzed. By analyzing their biological function and pathway, we may determine the effect of TGF-β at the early stage of wound repair.

Materials and methods

Microarray data

Gene expression omnibus (GEO; www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) contains original submitter-supplied records and curated DataSets, which is freely available to users. Two gene expression profiles (GSE79621 and GSE27165) were obtained from the GEO database. Data of fibroblast samples and TGF-β 24 h treated fibroblasts samples from the two gene expression profiles. The GSE79621 contained 3 fibroblast samples and 3TGF-β 24 h-treated fibroblast samples. The GSE27165 contained 2 fibroblast samples and 2 TGF-β 24 h-treated fibroblast samples.

Identification of DEGs

The data was processed using web-based tool Morpheus (https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus/), which is a matrix visualization and analysis platform designed to support visual data exploration. The expressions of mRNAs with Signal to noise >1 or signal to noise <1 was defined as DEGs. The co-expressed upregulated and downregulated DEGs of the two gene expression profiles were identified with a Venn Diagram (http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html; Venny 2.1.0).

GO and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis

The common upregulated and downregulated DEGs were analyzed using Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery version 6.7 (DAVID; david.ncifcrf.gov), an online program that provides a comprehensive set of function annotation tools for researchers to understand the biological meaning lists of genes. In order to analyze the DEGs at the function level, GO enrichment and KEGG pathway analyses were performed using DAVID. P<0.05 was considered to indicate statistically significant difference.

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis

To further understand the functional interactions between these DEGs a PPI network was used. The DEGs were mapped with the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING; www.string-db.org) and experimentally validated interactions with a combined score of >0.5 were selected as significant. Then, the PPI network was constructed and visualized using Cytoscape software (version 3.4.0). The top 10 essential nodes ranked by degree were selected. The plug-in Molecular Complex Detection (MCODE) was used to identify the modules of the PPI network in Cytoscape. The criteria were set as follows: MCODE score ≥4 and number of nodes >4. The function enrichment analysis of DEGs in the top module was performed using DAVID.

Results

Identification of DEGs

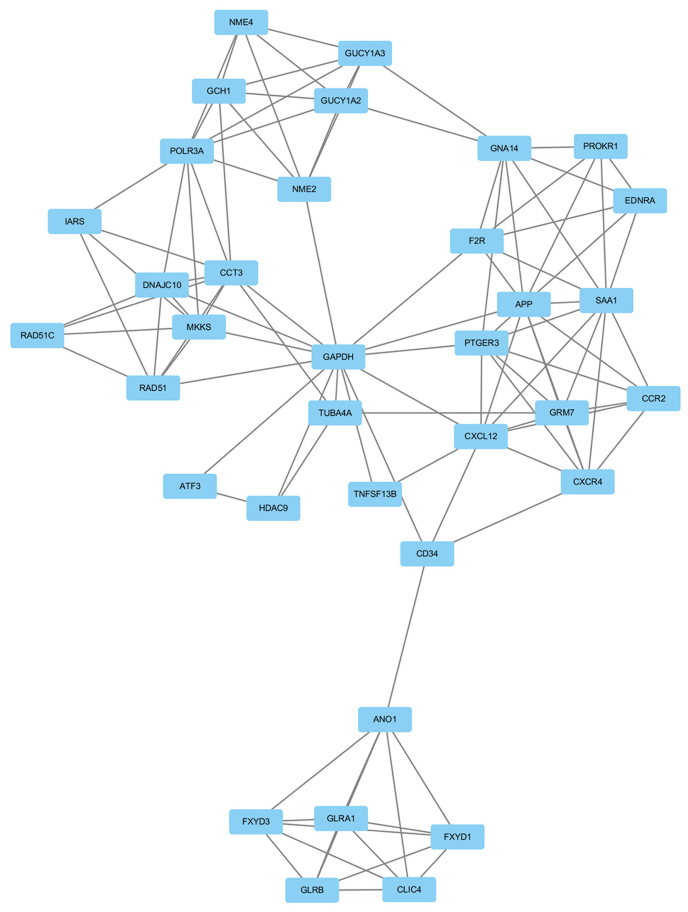

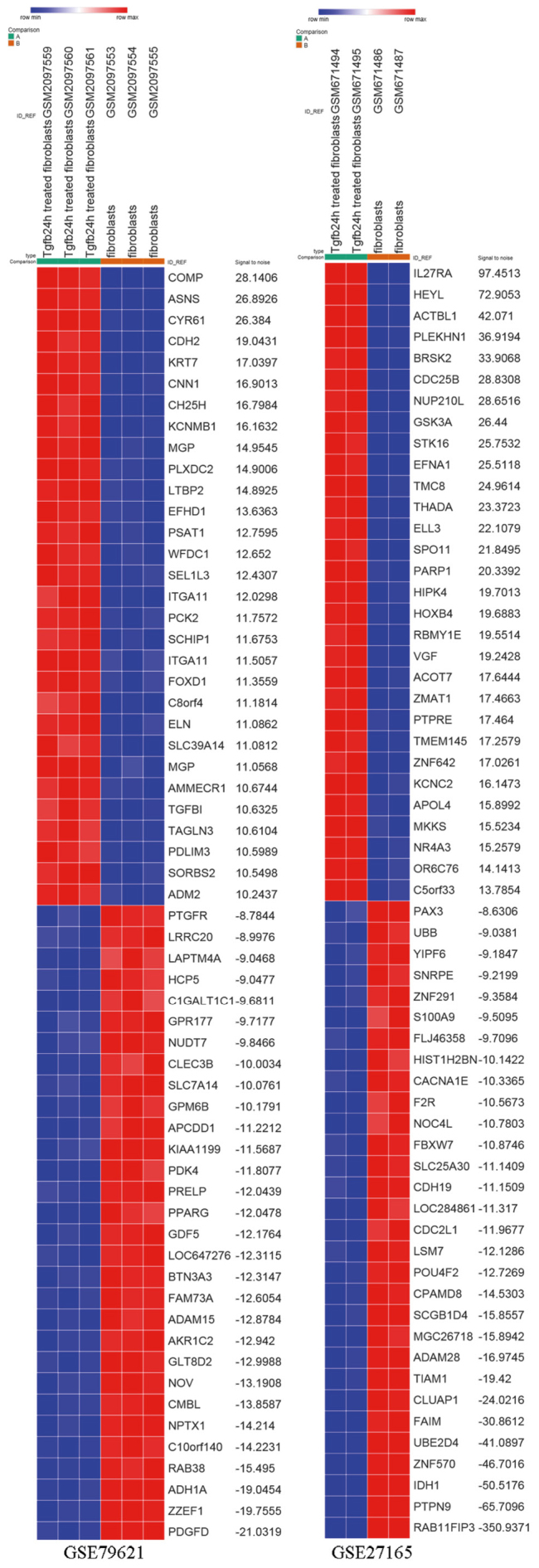

A total number of samples analyzed were 5 fibroblast samples and 5 TGF-β 24 h-treated fibroblast samples. The gene expression profiles were analyzed separately using Morpheus software. Then, a total of 4,211, 2,433 upregulated and 4,340, 2,032 downregulated DEGs were identified from the GSE79621 and GSE27165 datasets, respectively. DEG expression heat map of the top 30 upregulated and downregulated genes of the two gene expression profiles are shown in Fig. 1. The 385 upregulated and 398 downregulated co-expressed genes were identified in the two gene expression profiles (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Heat map of the top 60 differentially expressed genes of GSE79621 and GSE27165 (30 upregulated and 30 downregulated). Red, upregulation; blue, downregulation.

Figure 2.

Co-expression of upregulated and downregulated genes in GSE79621 and GSE27165.

GO term enrichment

The upregulated and downregulated DEGs were loaded to the DAVID software to identify GO categories and KEGG pathways. GO analysis results showed that in biological process, upregulated DEGs were significantly enriched in Arp2/3 complex-mediated actin nucleation, positive regulation of hyaluronan cable assembly, purine nucleobase biosynthetic process, de novo IMP biosynthetic process, and positive regulation of epithelial cell proliferation, whereas the downregulated DEGs were enriched in regulation of blood pressure, negative regulation of cell proliferation, ossification, negative regulation of gene expression and the type I interferon signaling pathway (Table I).

Table I.

GO analysis of upregulated and downregulated differentially expressed genes in biological processes.

| A, Upregulated | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Term | Function | Count | P-value |

| GO:0034314 | Arp2/3 complex-mediated actin nucleation | 5 | 6.98×10−4 |

| GO:1900106 | Positive regulation of hyaluranon cable assembly | 3 | 0.001053124 |

| GO:0009113 | Purine nucleobase biosynthetic process | 3 | 0.003423324 |

| GO:0006189 | De novo IMP biosynthetic process | 3 | 0.005071039 |

| GO:0050679 | Positive regulation of epithelial cell proliferation | 6 | 0.006688708 |

| B, Downregulated | |||

| Term | Function | Count | P-value |

| GO:0008217 | Regulation of blood pressure | 9 | 5.66 ×10−5 |

| GO:0008285 | Negative regulation of cell proliferation | 18 | 0.00333738 |

| GO:0001503 | Ossification | 7 | 0.005354786 |

| GO:0010629 | Negative regulation of gene expression | 9 | 0.006461428 |

| GO:0060337 | Type I interferon signaling pathway | 6 | 0.00863459 |

GO, gene ontology.

KEGG pathway analysis

The KEGG pathway analysis of upregulated and downregulated DEGs was performed using DAVID is presented in Table II. The top 5 KEGG pathways of upregulated DEGs were shigellosis, pathogenic Escherichia coli infection, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway, Ras signaling pathway and bacterial invasion of epithelial cells. The top 5 KEGG pathways of downregulated DEGs were systemic lupus erythematosus, lysosome, arachidonic acid metabolism, thyroid cancer and allograft rejection (Table II).

Table II.

KEGG pathway analysis of upregulated and downregulated differentially expressed genes. Top 5 terms were selected according to P-value when more than five terms enriched terms were identified in each category.

| A, Upregulated | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway ID | Name | Count | P-value | Genes |

| hsa05131 | Shigellosis | 8 | 5.30×10−4 | ACTB, ARPC2, NFKBIB, ARPC5L, ARPC4, MAPK11, MAPK10, FBXW11 |

| hsa05130 | Pathogenic Escherichia coli infection | 6 | 0.005446999 | ACTB, TUBB, ARPC2, ARPC5L, TUBA4A, ARPC4 |

| hsa04010 | MAPK signaling pathway | 13 | 0.011844961 | NTF3, MRAS, MAPK11, MAPK10, ARRB2, RASGRP1, RASGRP2, PRKACB, FGF1, MYC, GADD45A, RASA1, NFATC1 |

| hsa04014 | Ras signaling pathway | 12 | 0.012462871 | LAT, GRIN2B, MRAS, HTR7, RASGRP1, VEGFA, RASGRP2, GNB4, PRKACB, MAPK10, FGF1, RASA1 |

| hsa05100 | Bacterial invasion of epithelial cells | 6 | 0.030311184 | ACTB, ARPC2, ARPC5L, ARPC4, CD2AP, FN1 |

| B, Downregulated | ||||

| Pathway ID | Name | Count | P-value | Genes |

| hsa05322 | Systemic lupus erythematosus | 10 | 0.006763183 | HIST2H2AA3, HIST1H2AC, HIST1H2BD, HIST1H2BK, HIST2H2BE, HIST2H2AC, HLA-DPA1, C1R, C1S, CD40 |

| hsa04142 | Lysosome | 9 | 0.011440506 | CTSK, LAMP2, TPP1, GUSB, SMPD1, PPT2, NEU1, ATP6V0A4, IDUA |

| hsa00590 | Arachidonic acid metabolism | 6 | 0.019902025 | PLA2G4A, TBXAS1, PTGS1, EPHX2, LTA4H, PLA2G4C |

| hsa05216 | Thyroid cancer | 4 | 0.036016354 | TCF7, RXRA, TFG, TCF7L1 |

| hsa05330 | Allograft rejection | 4 | 0.066232041 | HLA-C, HLA-DPA1, HLA-B, CD40 |

KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

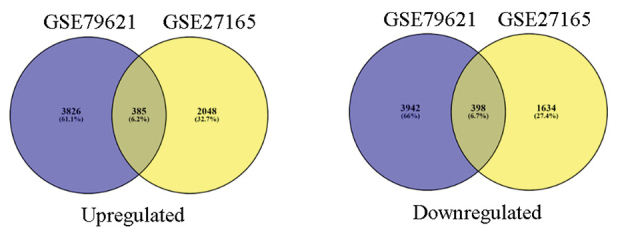

PPI network construction and module analysis

Based on the information in the STRING and Cytoscape databases, the top 10 hub nodes with high degrees were identified. These hub genes were GAPDH, MYC, CDK1, ACTB, APP, PRKACB, MAKP11, ACACB, HSPA4, CAT (Table III). GAPDH had the highest node degree, which was 83. A total of 6 modules from the PPI network satisfied the criteria of MCODE scores ≥4 and number of nodes >4 (Table IV). The GO and KEGG pathway enrichment of the genes were included in the top module (Fig. 3) revealed that these genes were primarily associated with chloride transmembrane transport, chloride transport, positive regulation of cytosolic calcium ion concentration, chloride channel complex, chloride channel activity, GTP binding, extracellular-glycine-gated chloride channel activity, neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, purine metabolism and intestinal immune network for IgA production (Table V).

Table III.

Degree of top 10 genes.

| Gene ID | Gene name | Degree | Expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 83 | Upregulation |

| MYC | Myc proto-oncogene protein | 55 | Upregulation |

| CDK1 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 | 51 | Downregulation |

| ACTB | Actin, cytoplasmic 1 | 50 | Upregulation |

| APP | Amyloid beta A4 protein | 40 | Downregulation |

| PRKACB | cAMP-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit beta | 36 | Upregulation |

| MAKP11 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 11 | 35 | Upregulation |

| ACACB | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase 2 | 34 | Downregulation |

| HSPA4 | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 4 | 31 | Upregulation |

| CAT | Catalase | 31 | Downregulation |

Table IV.

Six modules from the protein-protein interaction network satisfied the criteria of MCODE scores ≥4 and number of nodes >4.

| Cluster | Score | Nodes | Edges | Node IDs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6.353 | 35 | 108 | FXYD1, ANO1, FXYD3, CD34, POLR3A, GCH1, GNA14, CCR2, NME4, EDNRA, NME2, GUCY1A3, GUCY1A2, PTGER3, PROKR1, HDAC9, TNFSF13B, TUBA4A, DNAJC10, CCT3, GLRB, GLRA1, IARS, CLIC4, CXCL12, CXCR4, RAD51C, GRM7, F2R, RAD51, GAPDH, MKKS, APP, SAA1, ATF3 |

| 2 | 4.8 | 6 | 12 | MRAS, LRRC2, FMOD, RAP2C, MST4, PDE7B |

| 3 | 4.5 | 9 | 18 | HLA-B, IRF4, GLDC, ACACB, OAS3, GART, PMPCB, IFIT3, HLA-C |

| 4 | 4.5 | 5 | 9 | WDR4, CECR1, WDR12, PUS1, PUS7 |

| 5 | 4.3 | 21 | 43 | MYC, DHX9, MDM2, MCL1, VAMP1, YWHAG, RABL6, UPF2, STX16, TUBB, NUDT21, RAB6A, NSF, RPL37, RPL22, TUBB4Q, PHF5A, ACTB, VAMP4, STX6, AR |

| 6 | 4 | 4 | 6 | COL6A2, COL13A1, COL4A4, COL11A1 |

Score = (Density × no. of nodes).

Figure 3.

Top module from the protein-protein interaction network.

Table V.

Functional and pathway enrichment analysis of the genes in module. Top 3 terms were selected according to P-value when more than 3 terms enriched terms were identified in each category.

| A, Biological processes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Term | Name | Count | P-value | Genes |

| GO:1902476 | Chloride transmembrane transport | 6 | 1.15×10−6 | FXYD1, GLRB, FXYD3, GLRA1, CLIC4, ANO1 |

| GO:0006821 | Chloride transport | 5 | 1.22×10−6 | FXYD1, FXYD3, GLRA1, CLIC4, ANO1 |

| GO:0007204 | Positive regulation of cytosolic calcium ion concentration | 6 | 8.60×10−6 | EDNRA, PTGER3, CXCR4, SAA1, CCR2, F2R |

| B, Molecular functions | ||||

| Term | Name | Count | P-value | Genes |

| GO:0005254 | Chloride channel activity | 4 | 2.02×10−4 | FXYD1, FXYD3, CLIC4, ANO1 |

| GO:0005525 | GTP binding | 5 | 0.007953298 | GNA14, GUCY1A2, GUCY1A3, TUBA4A, GCH1 |

| GO:0016934 | Extracellular-glycine-gated chloride channel activity | 2 | 0.010379054 | GLRB, GLRA1 |

| C, KEGG pathways | ||||

| Term | Name | Count | P-value | Genes |

| hsa04080 | Neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction | 6 | 0.003899897 | EDNRA, GLRB, PTGER3, GLRA1, GRM7, F2R |

| hsa00230 | Purine metabolism | 5 | 0.00451383 | NME4, NME2, GUCY1A2, GUCY1A3, POLR3A |

| hsa04672 | Intestinal immune network for IgA production | 3 | 0.014264846 | TNFSF13B, CXCR4, CXCL12 |

KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

Discussion

Despite advancements in the understanding of the mechanism of wound repair, an effective method for accelerating the process remains to be identified. Investigation of the complicated molecular mechanism of wound repair is of important for treatment, particularly of chronic traumatic wounds, diabetic foot and bedsores. Previous studies (31,32) have focused on the effect of vascular endothelial cells, epithelial cells and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in wound and the effect of fibroblasts remains to be determined. The proliferation phase ensues with fibroblast migration, which then synthesize ECM components, which have a significant role in each stage of the healing process. TGF-β contributes to the function of fibroblasts, including cell migration, collagen synthesis and cell proliferation. Therefore, understanding the effect of TGF-β on fibroblasts at the early proliferation stage is essential to identify an effective way to improve wound healing. The present study used bioinformatics analysis to investigate the effect of TGF-β on fibroblasts at the early proliferation stage of wound healing. Data from GSE79621 and GSE27165 was obtained and identified 385 upregulated and 398 downregulated overlapped DEGs between normal fibroblasts and TGF-β 24 h treated fibroblasts. In order to understand the interactions of DEGs, GO and KEGG pathway analyses were performed.

The GO term analysis showed that the upregulated DEGs were mainly involved in Arp2/3 complex-mediated actin nucleation, positive regulation of hyaluronan cable assembly, purine nucleobase biosynthetic process, de novo IMP biosynthetic process and positive regulation of epithelial cell proliferation. Previous studies have found that actin has an important role in cell migration (33–35). The GO term analysis in biological processes suggested that at the proliferation phase, TGF-β may regulate actin-based fibroblast migration to the wound site by Arp2/3 complex. Previous studies have demonstrated that fetal wounds consist of ECM with an abundance of hyaluronan (36,37). Hyaluronan is produced by fibroblasts and promotes fibroblasts migration and proliferation early in the repair process (37). Therefore, TGF-β-mediated hyaluronan synthesis may be essential for the migration and proliferation of fetal fibroblasts. In addition, the findings of the present study also suggest that TGF-β may regulate the biological activity of fibroblasts, purine nucleobase biosynthetic process and de novo IMP biosynthetic process. Furthermore, TGF-β is the only growth factor, which accelerates ‘maturation’ of epithelial cell layers (38), which is accordance with the current findings that TGF-β is related to the positive regulation of epithelial cell proliferation. The GO term analysis revealed that the downregulated DEGs were primarily involved in the regulation of blood pressure, negative regulation of cell proliferation, ossification, gene expression and the type I interferon signaling pathway. The regulation of blood pressure is a process controlled by a balance of processes that increase pressure and reduce pressure. A previous study determined that blood pressure is negatively regulated by TGF-β (39), which was consistent the current findings. Ossification is the conversion of fibrous tissue into bone or a bony substance. Inhibition of ossification by downregulation of genes (Bone morphogenic protein 1, Ras association domain-containing protein 2, neuronal membrane glycoprotein M6-b, atrial natriuretic peptide receptor 2, exostosin-1, V-type proton ATPase 116 kDa subunit a isoform 4 and extracellular matrix protein1) may imply that the early stage of wound healing is mainly associated with fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis. Increased levels of genes in the type I interferon pathway have been observed in dermal fibrosis (40). The regulation mechanism of type I interferon of dermal fibroblasts and its participation in the development of dermal fibrosis remains to be elucidated. The current findings suggest that TGF-β may inhibit the interferon signaling pathway of fibroblasts by downregulation of gene expression levels, thus preventing wound fibrosis at early stage. Previous studies have found that TGF-β could mediate cell proliferation (41,42) and collagen production (43,44). The GO term analysis demonstrated that downregulated genes were mainly enriched in negative regulation of cell proliferation and gene expression, suggesting that TGF-β could promote fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis at the early stage of wound healing by downregulating related genes. In addition, the enriched KEGG pathways of upregulated DEGs included shigellosis, pathogenic Escherichia coli infection, MAPK signaling pathway, Ras signaling pathway and bacterial invasion of epithelial cells. The pathway of shigellosis, pathogenic Escherichia coli infection and bacterial invasion of epithelial cells was associated with infection, suggesting that TGF-β has an antibacterial effect on the healing of infected wounds. Previous studies have demonstrated that activation the MAPK and Ras signaling pathways could promote cell proliferation, differentiation and migration (45,46). In addition, the top 5 KEGG pathways of the downregulated DEGs were systemic lupus erythematosus, lysosome, arachidonic acid metabolism, thyroid cancer and allograft rejection. The systemic lupus erythematosus pathway and allograft rejection pathways are associated with autoantibodies and could cause tissue injury. Lysosomes serve as the cell's main digestive compartment and macromolecules are delivered for degradation. However, previous studies have found (47) that ingested microparticles may induce cellular damage in phagocytes through the release of lysosomal enzymes following lysosome rupture. Arachidonic acid is oxygenated and further transformed into a variety of products, which mediate inflammatory reactions (48).

A PPI network was constructed from the DEGs by Cytoscape and the 10 genes exhibiting the highest degree of connectivity. From these 10 genes, 6 genes were upregulated (GAPDH, MYC, ACTB, PRKACB, MAKP11, HSPA4) and 4 genes (CDK1, APP, ACACB, CAT) were downregulated. The top hub gene GAPDH, encodes a member of the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase protein family, which catalyzes an important energy-yielding step in carbohydrate metabolism. A previous study has determined that GAPDH could maintain the integrity of a protein (49). Lin et al (50) reported that MYC plays a positive role in regulation of fibroblasts proliferation. ACTB encodes one of actin proteins, which are highly conserved proteins involved in various types of cell motility. A previous study determined that β-actin has a key role in cell growth and migration (51). The protein encoded by PRKACB is a member of the serine/threonine protein kinase family. The encoded protein is a catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase, which mediates signaling though cAMP. cAMP signaling is important for various processes, including cell proliferation and differentiation (52). MAKP11 encodes mitogen-activated protein kinase 11, which is a member of the protein kinases family. MAKP11 is involved in the integration of biochemical signals for a wide variety of cellular processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, transcriptional regulation and development (53,54). The activity of the heat shock protein A4 (HSPA4), a member of the HSP110 family, is inducible under various conditions (55). However, a previous study revealed that overexpression of HSPA4 may inhibit the migration of fibroblasts cells (56). The 4 downregulated hub genes were CDK1, APP, ACACB and CAT. CDK1, also termed CDC2, has a key role in the control of cell cycles and promotes cell migration and proliferation (49,57,58). APP encodes amyloid β A4 protein, an integral membrane protein largely known for its role as the precursor of A β peptides and for its involvement in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease (59). Previous studies have determined that sAPP, the secretory domain of the APP has been observed to reestablish cell growth in APP-deficient fibroblasts (60). Acetyl-CoA carboxylase β is encoded by ACACB regulates cellular metabolic processes and may be involved in the regulation of fatty acid oxidation. CAT encodes catalase, a key antioxidant enzyme in the defense against oxidative stress. Downregulation of ACACB and CAT may promote wound repair through prevention of oxidative stress (61). It is of note that at the early proliferation stage of wound repair, fibroblasts migrate to the wound site from surrounding tissue, and contribute to the proliferation and synthesis ECM components. However, the current study revealed that TGF-β upregulated the expression level of HSPA4 and downregulated the level of CDK1 at the early wound healing stage. It is of note that previous studies determined that overexpression of HSPA4 and reduced expression of CDK1 may inhibit cell migration and proliferation (56,58). Therefore, TGF-β may inhibit excessive fibroblast migration and proliferation by meditating the expression level of different genes. Therefore, further investigation is required in order to clarify the underlying biological mechanisms of HSPA4 and CDK1 on fibroblasts at the early wound healing stage.

A previous study revealed that ion channels and transporters have a key role in cellular functions (62). Their physiological roles in cell proliferation have been considered, as cell volume changes, which involves the movement of ions across the cell membrane, which is essential for cell-cycle progression (63,64). The biological process and molecular function analysis identified one module that contained genes mainly enriched in chloride and calcium channels, which also suggested that ions are important in fibroblast migration and proliferation. However, the mechanism behind this the regulation of this process by ion channels is still unclear. Therefore, future studies should investigate the genes associated with ion channels to elucidate how TGF-β mediated ion channels and in turn cellular functions. Furthermore, the pathway analysis revealed that the effect of TGF-β on fibroblasts was associated with neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, purine metabolism and intestinal immune network for IgA production. A previous study determined that fibroblasts could interact with other cells during the process of wound repair (65). It is of note that, tenascin-C derived from fibroblasts could promote Schwann cell migration to the wound site and peripheral nerve regeneration (66). It has been established that purine metabolites provide a cell with the necessary energy to promote cell progression (56,67). One feature of intestinal immunity is its ability to generate non-inflammatory immunoglobulin A antibodies that act as the first line of defense against microorganisms. The aforementioned GO and KEGG pathway analyses of the top module suggest that TGF-β could promote fibroblast proliferation, migration and have an antimicrobial effect.

The current study has several limitations. Firstly, the sample size was small and samples were not directly obtained from the wound. Wound repair is a complex interaction process and except TGF-β, other cytokines also have effect on fibroblasts. Secondly, the proliferation stage may continue for 3–10 days and TGF-β may regulate other genes included in fibroblasts. Thirdly, these finding would benefit from a validation by western blotting and polymerase chain reaction. However, the present findings may suggest potential methods to investigate the effect of TGF-β on fibroblasts. In addition, future studies will be designed to clarify the role of TGF-β on fibroblasts during the early stage of wound repair.

In conclusion, the current study provided a comprehensive bioinformatics analysis of DEGs, which was associated with the effect of TGF-β on fibroblasts at the early proliferation phase of wound repair. The current study provided a set of useful target genes and pathways for further investigation into the molecular mechanisms of wound repair. In addition, the current study may provide a novel research method, which is rarely used in wound repair. Additional clinical samples are required to confirm the DEGs of fibroblasts affected by TGF-β during wound repair.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr Liming Xiong for the support and the design idea for the current study.

References

- 1.Ueha S, Shand FH, Matsushima K. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of chronic inflammation-associated organ fibrosis. Front Immunol. 2012;3:71. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacinto A, Martinez-Arias A, Martin P. Mechanisms of epithelial fusion and repair. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:E117–E123. doi: 10.1038/35074643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baer ML, Colello RJ. Endogenous bioelectric fields: A putative regulator of wound repair and regeneration in the central nervous system. Neural Regen Res. 2016;11:861–864. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.184446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie SY, Peng LH, Shan YH, Niu J, Xiong J, Gao JQ. Adult stem cells seeded on electrospinning silk fibroin nanofiberous scaffold enhance wound repair and regeneration. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2016;16:5498–5505. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2016.11730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith-Bolton R. Drosophila imaginal discs as a model of epithelial wound repair and regeneration. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2016;5:251–261. doi: 10.1089/wound.2014.0547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang S, Ma K, Geng Z, Sun X, Fu X. Oriented cell division: New roles in guiding skin wound repair and regeneration. Biosci Rep. 2015;35:pii: e00280. doi: 10.1042/BSR20150225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng LH, Wei W, Shan YH, Zhang TY, Zhang CZ, Wu JH, Yu L, Lin J, Liang WQ, Khang G, Gao JQ. β-Cyclodextrin-linked polyethylenimine nanoparticles facilitate gene transfer and enhance the angiogenic capacity of mesenchymal stem cells for wound repair and regeneration. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2015;11:680–690. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2015.1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kotwal GJ, Sarojini H, Chien S. Pivotal role of ATP in macrophages fast tracking wound repair and regeneration. Wound Repair Regen. 2015;23:724–727. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shingyochi Y, Orbay H, Mizuno H. Adipose-derived stem cells for wound repair and regeneration. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2015;15:1285–1292. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2015.1053867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eming SA, Martin P, Tomic-Canic M. Wound repair and regeneration: Mechanisms, signaling, and translation. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:265sr6. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu S, Sang L, Zhang Y, Wang X, Li X. Biological evaluation of human hair keratin scaffolds for skin wound repair and regeneration. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2013;33:648–655. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sen CK, Roy S. OxymiRs in cutaneous development, wound repair and regeneration. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23:971–980. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reinke JM, Sorg H. Wound repair and regeneration. Eur Surg Res. 2012;49:35–43. doi: 10.1159/000339613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li H, Fu X. Mechanisms of action of mesenchymal stem cells in cutaneous wound repair and regeneration. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;348:371–377. doi: 10.1007/s00441-012-1393-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eldardiri M, Martin Y, Roxburgh J, Lawrence-Watt DJ, Sharpe JR. Wound contraction is significantly reduced by the use of microcarriers to deliver keratinocytes and fibroblasts in an in vivo pig model of wound repair and regeneration. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:587–597. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peng LH, Tsang SY, Tabata Y, Gao JQ. Genetically-manipulated adult stem cells as therapeutic agents and gene delivery vehicle for wound repair and regeneration. J Control Release. 2012;157:321–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu X, Li H. Mesenchymal stem cells and skin wound repair and regeneration: Possibilities and questions. Cell Tissue Res. 2009;335:317–321. doi: 10.1007/s00441-008-0724-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, Longaker MT. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008;453:314–321. doi: 10.1038/nature07039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yao F, Eriksson E. Gene therapy in wound repair and regeneration. Wound Repair Regen. 2000;8:443–451. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2000.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puchelle E. Airway epithelium wound repair and regeneration after injury. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg. 2000;54:263–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clark LD, Clark RK, Heber-Katz E. A new murine model for mammalian wound repair and regeneration. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;88:35–45. doi: 10.1006/clin.1998.4519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sicard RE, Nguyen LM. An in vivo model for evaluating wound repair and regeneration microenvironments. In Vivo. 1996;10:477–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suga H, Sugaya M, Fujita H, Asano Y, Tada Y, Kadono T, Sato S. TLR4, rather than TLR2, regulates wound healing through TGF-β and CCL5 expression. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;73:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee MJ, Shin JO, Jung HS. Thy-1 knockdown retards wound repair in mouse skin. J Dermatol Sci. 2013;69:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu J, Wang Y, Pan Q, Su Y, Zhang Z, Han J, Zhu X, Tang C, Hu D. Wnt/β-catenin pathway forms a negative feedback loop during TGF-β1 induced human normal skin fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition. J Dermatol Sci. 2012;65:38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen J, Zeng B, Yao H, Xu J. The effect of TLR4/7 on the TGF-β-induced Smad signal transduction pathway in human keloid. Burns. 2013;39:465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diegelmann RF, Evans MC. Wound healing: An overview of acute, fibrotic and delayed healing. Front Biosci. 2004;9:283–289. doi: 10.2741/1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elgaaen BV, Olstad OK, Sandvik L, Odegaard E, Sauer T, Staff AC, Gautvik KM. ZNF385B and VEGFA are strongly differentially expressed in serous ovarian carcinomas and correlate with survival. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li C, Zhen G, Chai Y, Xie L, Crane JL, Farber E, Farber CR, Luo X, Gao P, Cao X, Wan M. RhoA determines lineage fate of mesenchymal stem cells by modulating CTGF-VEGF complex in extracellular matrix. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11455. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al-Rekabi Z, Wheeler MM, Leonard A, Fura AM, Juhlin I, Frazar C, Smith JD, Park SS, Gustafson JA, Clarke CM, et al. Activation of the IGF1 pathway mediates changes in cellular contractility and motility in single-suture craniosynostosis. J Cell Sci. 2016;129:483–491. doi: 10.1242/jcs.175976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chigurupati S, Mughal MR, Okun E, Das S, Kumar A, McCaffery M, Seal S, Mattson MP. Effects of cerium oxide nanoparticles on the growth of keratinocytes, fibroblasts and vascular endothelias cells in cutaneous wound healing. Biomaterials. 2013;34:2194–2201. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.11.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao H, Han T, Hong X, Sun D. Adipose differentiation-related protein knockdown inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration and attenuates neointima formation. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:3079–3086. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ridley AJ, Schwartz MA, Burridge K, Firtel RA, Ginsberg MH, Borisy G, Parsons JT, Horwitz AR. Cell migration: Integrating signals from front to back. Science. 2003;302:1704–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.1092053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Le Clainche C, Carlier MF. Regulation of actin assembly associated with protrusion and adhesion in cell migration. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:489–513. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fotedar R, Margolis RL. WISp39 and Hsp90: Actin' together in cell migration. Oncotarget. 2015;6:17871–17872. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mast BA, Diegelmann RF, Krummel TM, Cohen IK. Hyaluronic acid modulates proliferation, collagen and protein synthesis of cultured fetal fibroblasts. Matrix. 1993;13:441–446. doi: 10.1016/S0934-8832(11)80110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Balaji S, King A, Marsh E, LeSaint M, Bhattacharya SS, Han N, Dhamija Y, Ranjan R, Le LD, Bollyky PL, et al. The role of interleukin-10 and hyaluronan in murine fetal fibroblast function in vitro: Implications for recapitulating fetal regenerative wound healing. PLoS One. 2015;10:e124302. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu YS, Chen SN. Apoptotic cell: Linkage of inflammation and wound healing. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:1. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsuki K, Hathaway CK, Lawrence MG, Smithies O, Kakoki M. The role of transforming growth factor β1 in the regulation of blood pressure. Curr Hypertens Rev. 2014;10:223–238. doi: 10.2174/157340211004150319123313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Agarwal SK, Wu M, Livingston CK, Parks DH, Mayes MD, Arnett FC, Tan FK. Toll-like receptor 3 upregulation by type I interferon in healthy and scleroderma dermal fibroblasts. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R3. doi: 10.1186/ar3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Y, Alexander PB, Wang XF. TGF-β family signaling in the control of cell proliferation and survival. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2017;9:pii: a022145. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a022145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DiRenzo DM, Chaudhary MA, Shi X, Franco SR, Zent J, Wang K, Guo LW, Kent KC. A crosstalk between TGF-β/Smad3 and Wnt/beta-catenin pathways promotes vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Cell Signal. 2016;28:498–505. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghosh AK, Mori Y, Dowling E, Varga J. Trichostatin A blocks TGF-beta-induced collagen gene expression in skin fibroblasts: Involvement of Sp1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;354:420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu J, Shi J, Li M, Gui B, Fu R, Yao G, Duan Z, Lv Z, Yang Y, Chen Z, et al. Activation of AMPK by metformin inhibits TGF-β-induced collagen production in mouse renal fibroblasts. Life Sci. 2015;127:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2015.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang W, Liu HT. MAPK signal pathways in the regulation of cell proliferation in mammalian cells. Cell Res. 2002;12:9–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takino K, Ohsawa S, Igaki T. Loss of Rab5 drives non-autonomous cell proliferation through TNF and Ras signaling in Drosophila. Dev Biol. 2014;395:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gause WC, Wynn TA, Allen JE. Type 2 immunity and wound healing: Evolutionary refinement of adaptive immunity by helminths. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:607–614. doi: 10.1038/nri3476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Samuelsson B. Arachidonic acid metabolism: Role in inflammation. Z Rheumatol. 1991;50(Suppl 1):S3–S6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen X, Stauffer S, Chen Y, Dong J. Ajuba Phosphorylation by CDK1 Promotes Cell Proliferation and Tumorigenesis. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:14761–14772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.722751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin L, Zhang JH, Panicker LM, Simonds WF. The parafibromin tumor suppressor protein inhibits cell proliferation by repression of the c-myc proto-oncogene; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 2008; pp. 17420–17425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bunnell TM, Burbach BJ, Shimizu Y, Ervasti JM. β-Actin specifically controls cell growth, migration, and the G-actin pool. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:4047–4058. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-06-0582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu D, Huang Y, Bu D, Liu AD, Holmberg L, Jia Y, Tang C, Du J, Jin H. Sulfur dioxide inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation via suppressing the Erk/MAP kinase pathway mediated by cAMP/PKA signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1251. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiang Y, Chen C, Li Z, Guo W, Gegner JA, Lin S, Han J. Characterization of the structure and function of a new mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38beta) J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17920–17926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hsu YL, Wang MY, Ho LJ, Huang CY, Lai JH. Up-regulation of galectin-9 induces cell migration in human dendritic cells infected with dengue virus. J Cell Mol Med. 2015;19:1065–1076. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adachi T, Sakurai T, Kashida H, Mine H, Hagiwara S, Matsui S, Yoshida K, Nishida N, Watanabe T, Itoh K, et al. Involvement of heat shock protein a4/apg-2 in refractory inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:31–39. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sakurai T, Kashida H, Hagiwara S, Nishida N, Watanabe T, Fujita J, Kudo M. Heat shock protein A4 controls cell migration and gastric ulcer healing. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:850–857. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3561-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Z, Fan M, Candas D, Zhang TQ, Qin L, Eldridge A, Wachsmann-Hogiu S, Ahmed KM, Chromy BA, Nantajit D, et al. Cyclin B1/Cdk1 coordinates mitochondrial respiration for cell-cycle G2/M progression. Dev Cell. 2014;29:217–232. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Han IS, Seo TB, Kim KH, Yoon JH, Yoon SJ, Namgung U. Cdc2-mediated Schwann cell migration during peripheral nerve regeneration. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:246–255. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dawkins E, Small DH. Insights into the physiological function of the β-amyloid precursor protein: Beyond Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem. 2014;129:756–769. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saitoh T, Sundsmo M, Roch JM, Kimura N, Cole G, Schubert D, Oltersdorf T, Schenk DB. Secreted form of amyloid beta protein precursor is involved in the growth regulation of fibroblasts. Cell. 1989;58:615–622. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90096-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ponugoti B, Xu F, Zhang C, Tian C, Pacios S, Graves DT. FOXO1 promotes wound healing through the up-regulation of TGF-β1 and prevention of oxidative stress. J Cell Biol. 2013;203:327–343. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201305074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang YL, Sun GY, Zhang Y, He JJ, Zheng S, Lin JN. Tormentic acid inhibits H2O2-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in rat vascular smooth muscle cells via inhibition of NF-kB signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14:3559–3564. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ohsawa R, Miyazaki H, Niisato N, Shiozaki A, Iwasaki Y, Otsuji E, Marunaka Y. Intracellular chloride regulates cell proliferation through the activation of stress-activated protein kinases in MKN28 human gastric cancer cells. J Cell Physiol. 2010;223:764–770. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bear CE. Phosphorylation-activated chloride channels in human skin fibroblasts. Febs Lett. 1988;237:145–149. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80189-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sorrell JM, Caplan AI. Fibroblasts-a diverse population at the center of it all. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2009;276:161–214. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(09)76004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang Z, Yu B, Gu Y, Zhou S, Qian T, Wang Y, Ding G, Ding F, Gu X. Fibroblast-derived tenascin-C promotes Schwann cell migration through β1-integrin dependent pathway during peripheral nerve regeneration. Glia. 2016;64:374–385. doi: 10.1002/glia.22934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pedley AM, Benkovic SJ. A new view into the regulation of purine metabolism: The purinosome. Trends Biochem Sci. 2017;42:141–154. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]