Abstract

Despite the crucial role of mentoring, little literature exists that addresses distance mentoring among health researchers. This article provides three case studies showcasing protégés at different stages of career development (one in graduate school, one as an early-stage researcher, and one as an established researcher). Each case study provides a brief history of the relationship, examines the benefits and challenges of working together at a distance, and discusses the lessons learned from both the mentor and the protégé over the course of these relationships. A mentoring model, examples of mentoring communications, and potential promising practices are also provided and discussed.

Keywords: collaborative learning, communication, distance learning, e-mentoring, mentor, professional development, protégé, psychological development

Mentoring is an important factor in the career-development trajectory of the protégé, with effective mentoring exerting a positive influence and ineffective mentoring often exerting a negative influence (e.g. Straus et al., 2013; Zerzan et al., 2009). High-quality mentor–protégé relationships also contribute to greater career satisfaction for the protégé and mentor (e.g. Allen et al., 2006; DeCastro et al., 2014; Ratnapalan, 2010). Additionally, mentoring may address important challenges that the protégé may face and provide needed support for specific issues (e.g. diversity; Burney et al., 2009; Jeste et al., 2009; Yager et al., 2007). Mentoring relationships and mentoring programs exist across the globe and in many fields including health research (Cole et al., 2016).

Traditionally, mentoring occurs face to face, with the mentor and protégé working together within the context of a formal relationship (e.g. advisor and student). The majority of literature on mentoring relationships focuses on traditional face-to-face relationships and presents both qualitative and quantitative data. Common advice that emerges from these papers includes having regular meetings, establishing realistic expectations, having a written agreement that specifies short- and long-term goals and methods for achieving these goals, ensuring mutual respect, maintaining reciprocity such that both members benefit from and enjoy the relationship, and the importance of programs that ensuring mentoring needs are met for both mentor and protege (e.g. Binkley and Brod, 2013; Kashiwagi et al., 2013; Rustgi and Hecht, 2011; Straus et al., 2013).

However, mentoring may also take place at a distance, with few (if any) meetings in person. The mentoring relationship may be established at a distance (e.g. identifying a mentor through a collaborative network, after meeting at a conference), a strategy that may be especially important if the protégé desires a specific type of mentor (e.g. an expert within a specific subfield, a diversity mentor) who is not available in the protégé’s department or institution. Or the relationship may develop traditionally and then become a distance relationship if the mentor and/or protégé move away (e.g. for personal reasons or for common career reasons, such as internships and jobs).

The scant literature on distance mentoring shows that it is possible to have effective distance-mentoring relationships for physical therapists (Stewart and Carpenter, 2009), information sciences students (Earl et al., 2004), nurses (Lach et al., 2013), global health consortiums (Cole et al., 2016), and postdoctoral fellows involved in clinical trials (Mbuagbaw and Thabane, 2013). However, some evidence suggests that mentoring from a distance may, in some circumstances, be less effective for the protégé and less satisfying for the mentor (Luckhaupt et al., 2005).

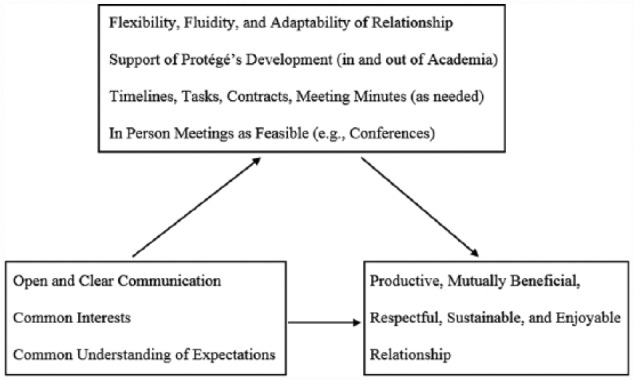

In this article, we focus on mentoring of health researchers, present case studies of three mentor–protégé relationships, and provide a model of distance mentoring (Figure 1) based on common components of the mentoring literature and our case studies. This article arose out of a conference symposium (Xu et al., 2016) where all authors spoke on the topic of distance mentoring. After a face-to-face discussion at the conference, we worked together on this article at a distance via email. After reflecting on their own practices, each pair wrote the initial draft of their case study and then received feedback from the other two pairs. All authors contributed to additional drafts of the case studies until a final version was reached that everyone approved. The first author (X.X.) initially drafted the introduction and discussion sections which were then revised and edited by all authors. There were many opportunities throughout this writing process for different viewpoints to be presented and statements to be refined until consensus emerged.

Figure 1.

A model of mentoring at a distance.

The case studies

Case study 1—pre-doctoral graduate student (A.L.D.) and mentor (J.P.A.)

While employed as the project manager of a federally funded randomized controlled trial at Columbia University, the protégé (A.L.D.) entered a program of study leading to the professional doctorate in health education at the outset of the 2012–2013 academic year. Being campus-based for the first 2 years of her program, she was able to complete most of her coursework for the degree and certification examination by the end of 2013–2014. It was at that time that she decided to relocate to Chicago to take a position as Executive Director of a non-profit organization and began working with her mentor (J.P.A.) at a distance.

Prior to A.L.D.’s decision to leave for a new professional opportunity, J.P.A. discussed with A.L.D. the potential obstacles that leaving a doctoral program before a dissertation and all requirements for the degree had been completed would present. J.P.A. explained that while completing a doctoral program at a distance would be challenging, it was possible to complete the degree (even though it would take longer) with a commitment to maintaining regular communication, agreeing on a timeline of key deliverables leading to the proposal and then to the completed dissertation, and scheduling one or two ad hoc meetings to confer while attending annual professional meetings. A.L.D. also had discussed a viable dissertation proposal idea by the time she departed but had not yet presented a fully developed written proposal to her committee.

During the 2014–2015 academic year—her first year away from campus—A.L.D. corresponded regularly with J.P.A. and committee via email and telephone calls. She also met with J.P.A., along with his other doctoral protégés, during annual professional meetings and made a return visit to campus to present her dissertation proposal in the doctoral seminar. During her return to campus, she worked with J.P.A. to refine the doctoral project and update the timeline going forward. In addition, J.P.A. traveled to one of the annual professional meetings that convened in Chicago, where J.P.A. and A.L.D. were able to meet in person to review progress, reiterate her most recent draft of the nascent dissertation, and set new goals. A.L.D. completed her independent study and remaining coursework online, including several intensive weekend classes in New York City.

Having completed a dissertation proposal and all of the necessary human subjects and other clearances by the end of the 2014 autumn semester, A.L.D. was prepared to begin data collection in the spring of 2015. With data collection completed by the end of that spring, she began conducting data analysis during the summer of 2015, anticipating writing the dissertation manuscript during the summer months and completing the work in time to defend by the end of 2015–2016. In the meantime, A.L.D. co-authored several manuscripts and received the Delbert Oberteuffer Doctoral Scholarship Award from the Society for Public Health Education, which supported her dissertation research in part.

With A.L.D. accelerating her efforts to complete her dissertation manuscript, J.P.A. sent an email (see Appendix A in Supplemental Material) during the early autumn of 2015 laying out key dates in the timeline moving forward that would enable her to complete the degree by May 2016. A.L.D., in turn, began submitting drafts of key elements of the dissertation manuscript by mid-academic year, with J.P.A. returning tracked edits of her draft chapters via email over several months of sustained effort. In addition, with the guidance of J.P.A., A.L.D. developed and submitted an abstract in response to a call for annual meeting presentations and, prior to the defense, began drafting one of the three manuscripts A.L.D., J.P.A., and the committee agreed would be among the three papers that would comprise her dissertation. A.L.D. completed her doctoral study and successfully defended her dissertation in the spring of 2016. This long-distance-mentoring approach thus extended her doctoral degree program period by approximately 1 year.

Case study 2—early-stage tenure-track researcher (X.X.) and mentor (C.N.)

In 2014, X.X. received a 1-year pilot grant from the Mountain West Clinical Translational Research – Infrastructure Network (MW CTR-IN). This grant stipulated that the principal investigator (PI) needed a mentor within the CTR-IN. X.X. utilized Vivo (vivoweb.org) to identify potential mentors with similar research interests. CTR-IN directors facilitated introductions, after which X.X. and C.N. spoke via phone and utilized email to come to consensus on goals and expectations for the year and to draw up a relationship contract. This included an agreement to meet monthly via phone and to exchange emails as needed. Further, C.N. requested X.X. to provide minutes for each monthly phone call (a sample was provided as a template by C.N.). These minutes (see Appendix B in Supplemental Material for an example) were helpful resources as they clearly stated the status of projects, what was discussed, goals, and agreed-upon plans of action and tasks.

Utilizing these monthly calls and as needed emails, X.X. set realistic goals and deadlines. C.N. advised X.X.’s research program, supported X.X.’s efforts, offered useful strategies to strengthen submissions, and assisted as an editor and co-author. Over the course of the year, C.N. and X.X. also met in person three times. One meeting was funded by the pilot grant (a 3-day trip wherein C.N. visited X.X.) and focused on grant writing. The other two meetings occurred during conferences where C.N. and X.X. presented collaborative work.

C.N. and X.X. also regularly discussed their collaborative relationship and explicitly conversed about the pros and cons of distance (in part, because this became an area of interest which evolved into this collaborative manuscript). Open communication allowed the relationship to remain flexible (e.g. increasing or decreasing calls based on research developments) and allowed both X.X. and C.N. to feel that they shared a common understanding about the relationship and positive expectations about each other (e.g. viewing the monthly calls and agreed-upon tasks as important priorities).

Within just a year the relationship yielded several positive work products, including four conference presentations, a publication, and an NIH grant application. Additionally (and perhaps more importantly), the relationship has been not only productive but also rewarding, fulfilling, and mutually beneficial, such that it has continued after the 1-year formal period. X.X. and C.N. continue to enjoy working together and engaging in ongoing collaborations, which have included presentations, manuscripts, and grant applications. C.N. also has significantly assisted X.X. with career development and networking opportunities, which have included meeting and collaborating with the other authors on this article. Finally, C.N. has been a great source of support for X.X., has delivered indispensable guidance on professional topics, and has provided an invaluable model of fulfilling work-life balance. These aspects of the mentoring relationship have helped X.X. move along (relatively) smoothly in her career, most recently by submitting her tenure and promotion materials.

Case study 3—established researcher (M.S.) and mentor (A.C.K.)

This mentor–protégé relationship formed its roots in the mid-1990s during the time that the protégé was an undergraduate student at the same university as the mentor. Having excelled in a course that was being taught by the mentor, the mentor asked the protégé to serve as a teaching assistant for the course, which she did. Out of that situation began a productive mentor–protégé relationship that has continued for three decades—both in-person during the formative phase of the relationship, and subsequently at-distance when the protégé moved to another university to begin graduate school.

A defining feature of this mentor–protégé relationship is that it was organic and unstructured. At no time during the past 30 years of distance mentoring has there been a written contract, a plan for regular contact, or an established understanding of the intended outcomes of the relationship. Rather, the respective roles of the mentor and the protégé have been fluid over time, the frequency of contact has waxed and waned, and the outcomes, while rewarding, have been largely unplanned.

Prior to the protégé’s departure to pursue doctoral studies, she joined the mentor’s ongoing research as a member of the recruitment team for an NIH-funded trial. This experience provided the protégé with valuable exposure to community-based health promotion research (a grounding that was to provide the foundation for the remainder of her career) and also afforded her the opportunity to demonstrate her work ethic to the mentor. Subsequently, after the protégé had initiated graduate studies at another institution, she returned for two summers to assist with research conducted by the mentor. This face-to-face time provided an opportunity for the protégé to seek input on a dissertation topic. Originally, discussions focused on a project that would involve collecting data at the mentor’s institution, but this option was ruled out eventually in favor of a similar project that involved collecting data at the protégé’s institution.

During this time, the protégé started attending the annual meetings of the Society of Behavioral Medicine (SBM) that became the backbone of the mentor–protégé relationship for the next 15–20 years. Once a year, at a minimum, there was an opportunity for a face-to-face meeting at this professional gathering, and this particular venue offered periodic opportunities for the mentor to open doors for the protégé toward continued professional development (e.g. invitations to become involved in SBM leadership roles). Early on, the mentor invited the protégé to join her as co-chair of a Special Interest Group. This appointment provided many opportunities for networking and for interacting with more senior colleagues. Later on, the mentor was elected President of SBM and nominated the protégé to become Program Chair of the annual conference (a highly visible position which facilitated forming ties with many established researchers in the field and provided an insiders’ view of the processes by which professional activities are developed and executed at the organizational level).

One aspect of the relationship that should not be overlooked is the value of having a letter of recommendation from a senior colleague outside of one’s own institution who can speak with extensive knowledge about the protégé based on years of familiarity. At critical transitions in academic progression—the jump from Assistant to Associate Professor, and the leap from Associate to Full Professor—external letters of recommendation are required and carry considerable weight. In this case, the mentor provided strong letters of recommendation for the promotion reviews, and these no doubt contributed to the protégé’s positive outcomes.

In addition to the instrumental aspects of the mentor–protégé relationship, this partnership has provided the protégé with critical emotional support at important career junctures. Because the protégé has been in a research track throughout her career (i.e. non-tenure track), she has faced certain challenges. Lack of mentorship at her home institution was one of those challenges, and this resulted in hurdles to career progression that came in the form of administrative barriers to progress. At these times, the mentor was able to provide perspective and advice on ways of overcoming these challenges and was able to do so with a neutral perspective that comes from being outside the institution.

Discussion

The three cases are summarized and presented alongside each other in Table 1, which reveals both similarities and unique differences. Some of the main underlying features of the three cases have also been integrated into a working model of distance mentoring (see Figure 1). As illustrated by the three case studies presented here, there are different ways to establish and maintain a distance-mentoring relationship. The relationship may begin at a distance without prior contact (Case 2) or in-person within the context of standard student-faculty roles (Cases 1 and 3), which allows both the mentor and protégé to get to know one another’s academic strengths, communication styles (and compatibility), and to build the mutual trust and respect which are vital for continuous mentoring at a distance.

Table 1.

Summary of the three case studies.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin of the relationship | Predoctoral student working with a faculty mentor | Pilot grant award stipulated requirement for a mentor within a specific network. | Undergraduate student enrolled in mentor’s class. |

| Timing and reason for distance mentoring | Student moved away to take an executive position with a non-profit company while still working on her dissertation | Protégé, who received the pilot grant award, subsequently found the mentor through vivoweb.org | Protégé moved to another institution to begin graduate school. |

| Definition of expectations | Verbal commitment to regular communication, agreement on a timeline of key deliverables, plan to meet ad hoc in conjunction with professional meetings. | Signed relationship contract including agreement to meet monthly via phone and exchange emails as needed. Protégé kept minutes of calls. | No formal agreement or expectations. |

| Duration of association (years) | 5 | 3 | 31 |

| Methods of ongoing communication | Regular phone calls and email | Monthly phone calls and ad hoc emails. | Flexible and irregular phone calls and emails. |

| Frequency of in-person meetings. | Protégé traveled to annual professional meeting to see her mentor and traveled to the mentor’s institution to refine the doctoral project plan. Mentor met with protégé during a professional meeting in the protégé’s home town. | In-person meetings three times during the year of the pilot study funding. The mentor visited the protégé’s institution for 3 days (using pilot grant funds) and two meetings occurred during professional conferences. | Annual meeting in conjunction with the annual conferences of a professional society. |

| Material benefits to the protégé | Dissertation was successfully proposed, completed, and defended. Abstract submitted to professional meeting, three manuscripts drafted. | Four conference presentations, one publication, and an NIH grant application. | A series of professional development opportunities: Research Assistant; co-chair (then Chair) of a Special Interest Group and Program Chair within a professional society; letters of recommendation for Promotion Reviews. |

| Non-material benefits to the protégé | Support to pursue a personally fulfilling professional opportunity without giving up doctoral studies. | Career development and networking opportunities. | Support and advice regarding professional advancement. |

| Non-material benefits to both mentor and protégé | Mutual respect, intellectual stimulation, and professional satisfaction. | ||

While each dyad and relationship will be unique, there are common components that contribute to rewarding experiences. Mutual interests (e.g. research area) and a shared understanding of the expectations of the relationship (which can be formalized, as in Cases 1 and 2, or organic, informal, and fluid, as in Case 3) are important starting points. Sharing mutual research interests also allows the mentor to recommend the protégé for relevant career development opportunities and identify regular opportunities for in-person meetings (e.g. conferences), which can further strengthen the mentoring bond and continually refresh the relationship. Conferences also provide a platform for the mentor to introduce the protégé to prominent research colleagues, to present collaborative work together, and to promote the protégé’s visibility and involvement in professional organizations.

Mentoring can be effective at many stages of the protégé’s career trajectory as long as the relationship continues to meet mutual evolving needs. Open and clear communications are vital throughout this process and allow for the continual re-evaluation and updating of the mentoring relationship. Depending on the career stage of the protégé and the dynamic of the dyad, formal components such as explicit timelines, assigned tasks, contracts, and meeting minutes may be especially helpful (e.g. Cases 1 and 2). However, flexibility of the mentoring relationship is important as well; for example, formal components may be useful when the protégé is working on a project with the mentor but unnecessary at other times (e.g. Case 3).

All three cases highlight the ways in which protégés can benefit professionally from the relationship (e.g. assistance with graduation, research, grant applications, presentations, manuscripts, networking, professional networking, and letters of recommendation). However, it is also important (particularly with distance mentoring where the protégé is less visible) that the mentor benefits from the relationship. These benefits include building a legacy, advancing science and future generations of researchers (subsequent mentors), engaging in developing novel research ideas and collaborations (including with others in the protégé’s network to whom the mentor now has access), and the pride that comes with seeing one’s protégé develop into an established member of the research community and field.

Protégés in all three cases were respectful of the mentor’s time and strategic in pursuing the mentor’s input and guidance. This enabled the relationship to be productive for the protégé and enjoyable for the mentor, without being burdensome. For all three case studies (but especially Case 3, which extends over decades), the personal affinity and mutual respect between a mentor and protégé brings satisfaction and enjoyment to both parties and helps ensure the continuation of the relationship. Moreover, this strong and positive relationship sets the stage for an adaptive dynamic that optimally benefits both partners across various contexts and allows the protégé to feel emotionally and practically supported for endeavors both in and out of academia.

Overall, the case studies revealed several themes that are consistent with past literature on positive mentoring relationships. These included open communication, mutual respect, collaborative interactions, and personal connection (e.g. DeCastro et al., 2014; Lach et al., 2013; Stewart and Carpenter, 2009; Straus et al., 2013), making time to meet including face-to-face when possible (e.g. Lach et al., 2013; Mbuagbaw and Thabane, 2013; Stewart and Carpenter, 2009), and having clear plans, goals, and expectations (e.g. Lach et al., 2013; Mbuagbaw and Thabane, 2013; Rustgi and Hecht, 2011). However, the case studies also highlighted some additional factors and alternatives to past themes. For example, Case 3 provides details on a very long-term (30+ years) and positive mentoring relationship that never had any formal components such as a plan for regular contact or an agreement on intended outcomes, but instead has been unstructured and extremely fluid. Unlike the majority of past mentoring research which has used surveys or interviews, these case studies also provide in-depth information on the origin of the relationship, how the relationship developed and evolved over time, and the material and non-material benefits to both protégés and mentors. In addition, the Supplemental Material contains real examples of correspondence and meeting minutes that may be helpful for those currently in distance-mentoring relationships or who are planning on beginning (or transitioning into) such a relationship.

The purpose of this article was to highlight positive distance-mentoring relationships so readers would have access to a potentially helpful model and useful examples. Future case studies and research could focus on negative distance-mentoring relationships and/or factors that contribute to negative/mixed outcomes as it would be helpful to have more information on practices that work as well as those that do not (or specific contexts that lead to better outcomes or increased struggles).

In conclusion, the three case studies provided highlight some potential promising practices for distance mentoring, which include the following:

Establish and nurture common interests.

Ensure a common understanding of expectations of the relationship and each other.

Maintain open and clear communication (utilize technology to enhance this).

Recognize and allow for flexibility/adaptability of the relationship over time.

Ensure support of protégé’s development (both in and out of the career trajectory).

Utilize timelines, tasks, contracts, and meeting minutes as needed.

Meet in person as feasible (e.g. conferences) and via technology (email, phone, video conferencing, etc.) when face-to-face interaction is not feasible.

Use these tips and other available resources to work toward a relationship that is mutually beneficial, productive, respectful, sustainable, and enjoyable.

Finally, protégés should keep in mind that they are not restricted to having only one mentor and that mentors often have more than one protégé with whom they are working. We encourage health researchers who need more or better mentoring than is available to reach out and establish relationships with potential mentors at other institutions, and for potential mentors to be open to these opportunities. While sometimes challenging, distance mentoring can be highly effective, beneficial, and rewarding to those involved, our research communities, and the future of a field’s scientific endeavors.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Xiaomeng Xu and Claudio R Nigg thank the Mountain West Clinical Translational Research—Infrastructure Network and NIGMS (1U54GM104944-01A1)—for their support in establishing and maintaining their mentoring relationship.

References

- Allen TD, Eby LT, Lentz E. (2006) Mentorship behaviors and mentorship quality associated with formal mentoring programs: Closing the gap between research and practice. Journal of Applied Psychology 91: 567–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binkley PF, Brod HC. (2013) Mentorship in an academic medical center. The American Journal of Medicine 126: 1022–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burney JP, Celeste BL, Johnson JD, et al. (2009) Mentoring professional psychologists: Programs for career development, advocacy, and diversity. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 40: 292–298. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DC, Johnson N, Mejia R, et al. (2016) Mentoring health researchers globally: Diverse experiences, programmes, challenges and responses. Global Public Health 11: 1093-1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCastro R, Griffith KA, Ubel PA, et al. (2014) Mentoring and the career satisfaction of male and female academic medical faculty. Academic Medicine 89: 301–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earl MF, Mack T, Southern J. (2004) Mentoring at a distance: Successful matching of experienced librarians with school of information sciences students via electronic and traditional means. Technical Services Quarterly 21: 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Jeste DV, Twamley EW, Cardenas V, et al. (2009) A call for training the trainers: Focus on mentoring to enhance diversity in mental health research. American Journal of Public Health 99(Suppl. 1): S31–S37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashiwagi DT, Varkey P, Cook DA. (2013) Mentoring programs for physicians in academic medicine: A systematic review. Academic Medicine 88: 1029–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lach HW, Hertz JE, Pomeroy SH, et al. (2013) The challenges and benefits of distance mentoring. Journal of Professional Nursing 29: 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Luckhaupt SE, Chin MH, Mangione CM, et al. (2005) Mentorship in academic general internal medicine: Results of a survey of mentors. Journal of General Internal Medicine 20: 1014–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbuagbaw L, Thabane L. (2013) How to set-up a long-distance mentoring program: A framework and case description of mentorship in HIV clinical trials. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare 6: 17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnapalan S. (2010) Mentoring in medicine. Canadian Family Physician 56: 198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustgi AK, Hecht GA. (2011) Mentorship in academic medicine. Gastroenterology 141: 789–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart S, Carpenter C. (2009) Electronic mentoring: An innovative approach to providing clinical support. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation 16: 199–206. [Google Scholar]

- Straus SE, Johnson MO, Marquez C, et al. (2013) Characteristics of successful and failed mentoring relationships: A qualitative study across two academic health centers. Academic Medicine 88: 82–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, DeSorbo-Quinn A, Schneider M, et al. (2016) Panel: Mentoring at a distance. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 50: S178. [Google Scholar]

- Yager J, Waitzkin H, Parker T, et al. (2007) Educating, training, and mentoring minority faculty and other trainees in mental health services research. Academic Psychiatry 31: 146–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerzan JT, Hess R, Schur E, et al. (2009) Making the most of mentors: A guide for mentees. Academic Medicine 84: 140–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.