Abstract

This study evaluated the effect of training pharmacists in the stage-of-change model for smoking cessation and motivational interviewing on smoking cessation outcomes. A training based on the stage-of-change model for smoking cessation and motivational interviewing was introduced to pharmacists. Pharmacists were randomly assigned to the intervention or control group. The control group attended a 3-hour training session, whereas the intervention group also attended a further 6-hour training session. At week 24, 12.2 percent of the smokers quit smoking in the intervention group, whereas 1.6 percent of the smokers quit smoking in the control group. The findings of this study showed that training pharmacists, in the stage-of-change model for smoking cessation and motivational interviewing, improves smoking reduction and cessation rates.

Keywords: adults, clinical health psychology, community health psychology, health promotion, nicotine dependence, public health psychology

Introduction

Cigarette smoking is the single most important cause of avoidable premature mortality in the world, and quitting is known to rapidly reduce the risk of serious diseases (World Health Organization (WHO), 2008). Death is mainly caused by lung cancer, coronary heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and stroke (Doll et al., 2004; US Department of Health Human Services, 2004). The risk of serious disease diminishes rapidly after quitting and permanent abstinence is known to reduce the risk of illness (Lightwood and Glantz, 1997; US Department of Health Human Services, 1990). Offering help to people addicted to nicotine is one of the six policies identified by the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) to expand the fight against the tobacco epidemic (WHO, 2009). However, smoking cessation turned out to be anything but simple, and for this reason, more and more clinicians and researchers consider it a complex learning process by nature (Lee et al., 2012).

Unfortunately, about 80 percent of smokers have no immediate intention to quit (Herzog and Blagg, 2007).

The efficacy of smoking cessation interventions in various clinical settings has been well documented, and studies have demonstrated that personal motivation (Curry et al., 1989; Lennox and Taylor, 1994) and ongoing support (Sinclair et al., 1995) can further improve smoking cessation rates. Community pharmacies have increased the accessibility of smoking cessation treatments such as “over-the-counter” (OTC) nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). In a preliminary study focused on experiences of customers in a community pharmacy setting (Sinclair et al., 1995), three-quarters of NRT users interviewed recalled having received some counseling from the pharmacist and/or the pharmacy assistant, and almost all of these customers felt that the counseling was helpful. However, more than a quarter did not recall receiving any counseling, and most of these customers reported they would have valued some smoking cessation counseling from a pharmacist.

Most pharmacists are eager to undertake a leading role in health promotion (Bond et al., 1993; Mertinez et al., 1993; National Audit Office, 1992). However, concerns have been raised that pharmacists are not trained for smoking cessation counseling and their advice may conflict with advice given from a patient’s general medical practitioner (Eaton and Webb, 1979; Roberts, 1988).

Training hospital doctors, general practitioners, and nurses in promoting and sustaining behavioral change among their patients has been shown to be effective for promoting smoking cessation (Cornuz et al., 2002; Tønnesen et al., 2007; Wallace-Bell, 2003).

This randomized controlled study, conducted in pharmacies in Sicily, Italy, evaluated the effect on pharmacy customers’ cessation outcomes when pharmacists were trained in the stage-of-change model for smoking cessation (Di Clemente, 2001) and motivational interviewing (MI) (Miller and Rollnick, 2013).

In this model, proposed by Prochaska and Di Clemente and colleagues, change is conceptualized as a process occurring in five stages: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation for action, action, and maintenance. In the context of cigarette addiction, the stage-of-change model proposes “stage-matched interventions” to treat cigarette addiction. It is hypothesized that smokers progress linearly through the five stages and may relapse to earlier stages. Each stage is characterized by the presence of divergent beliefs and attitudes toward smoking behavior. This model may assist in determining the type and range of interventions required by pharmacy personnel and tailoring interventions to the smoker’s current stage which may increase their likelihood of quitting (Di Clemente, 2001).

MI is widely used to help smokers quit. It is a patient-centered counseling approach for helping people to explore and resolve their ambivalence about changing their smoking behavior. Evidence suggests that MI by general practitioners and trained counselors motivates patients toward change (Miller and Rollnick, 2013). There is also evidence that MI may be more efficacious relative to other treatments with smokers who are low in motivation to quit (Hettema and Hendricks, 2010).

Customers seeking help with smoking cessation from pharmacy personnel are already beyond the “precontemplation” stage of the stage-of-change model. Rather, these customers are people who have reached the “contemplation” or “preparation” stage and may be intending to purchase a smoking cessation aid. For smokers who decide to stop smoking, pharmacotherapy increases the chances of success (Fiore et al., 2008). An understanding of the theory and practice of the stage-of-change model and MI could result in more effective counseling, by pairing the appropriate cessation advice to the stage of each customer and helping them resolve their ambivalences toward change. Well-designed smoking cessation training for pharmacists is needed. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study designed to assess the outcome of training pharmacists in the stage-of-change model of smoking cessation and MI.

We hypothesized that pharmacists who participated in a training based on the stage-of-change model and MI would be more effective than untrained controls to help people quit smoking and that many of their customers would achieve long-term abstinence from smoking. Hence, the main objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of the training on smoking cessation outcomes. The training included specific content and recommendations pertaining to preparation, action, maintenance, and relapse.

The focus of the training was to help participants develop an understanding of the key principles of the stage-of-change model and MI approach. Participants learned a series of brief questioning to assess the stages of change of their customers. Strategies to match the stage to the most appropriate intervention to promote cessation were emphasized.

Methods

A training based on the stage-of-change model of smoking cessation (Di Clemente, 2001) and MI (Miller and Rollnick, 2013) was conducted in February 2016, by the Centro per la Prevenzione e Cura del Tabagismo at the University of Catania. The training was previously piloted on a cross section of pharmacy personnel. Case studies of pharmacy customers, communication skills for negotiating change, and the importance of providing ongoing support, encouragement, and pharmacotherapy for cessation were included and emphasized in the training.

In September 2015, all 46 community pharmacies registered at Farmacia OK, a Sicilian Pharmacists’ Association, were invited to participate in the trial. A total of 42 pharmacies accepted the invitation and attended a 3-hour conference focused on the US Public Health Services 2008 Clinical Practice Guidelines for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence (Fiore et al., 2008). These guidelines align with the principles of MI and the stage-of-change model. Training for pharmacists in Italy does not include smoking cessation. Therefore, it was critical to expose participants to these internationally accepted evidence-based practice guidelines for tobacco dependence.

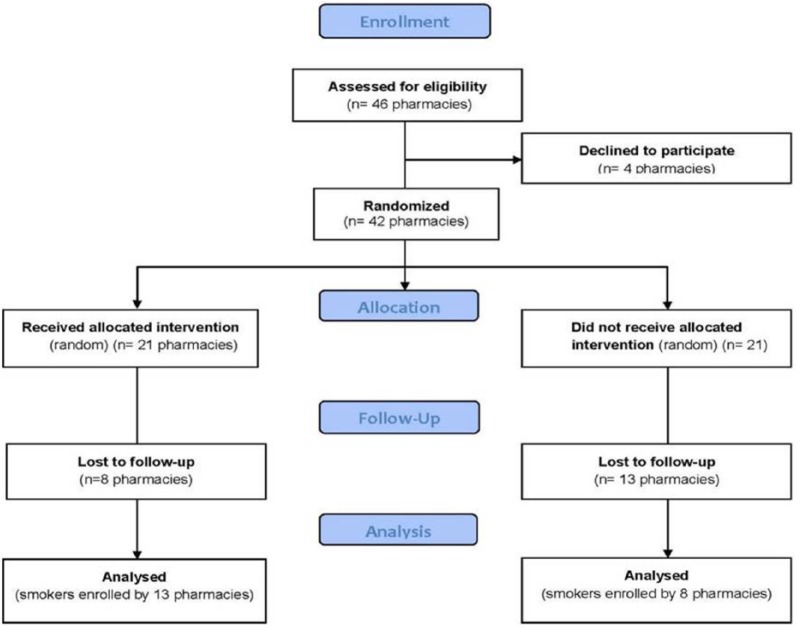

Successively, pharmacies were randomly allocated, by sequential allocation, to the intervention or control group (Figure 1). The intervention group attended a 6-hour training by scheduling an initiation workshop. The 6 hours of anti-smoking training teach the most skilled pharmacists to be more effective in making them able to help their smoking customers quit.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram.

During the 3-month customer recruitment period, all smokers who sought advice on smoking cessation or those who bought an OTC anti-smoking product in preparation for a new attempt to stop smoking were eligible for inclusion. Pharmacy personnel offered these customers a patient information sheet specific to their group (intervention or control) informing them that Farmacia OK pharmacists were working with researchers studying smoking cessation at the University of Catania and inviting them to join the study. Specifically, in the intervention group, smokers were informed that their pharmacists were trained to specific anti-smoking counseling based on stage-of-change and MI theories. In the control group, smokers were informed that their pharmacists recently attended a conference on “Clinical Practice Guidelines for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence.”

Pharmacy staff maintained a confidential client record which documented their progress in smoking cessation, any product supplied, points raised by the client, and advice given. At each of the planned follow-up visits, telephone call reminders were carried out to improve participation. However, customers were not made aware of their group allocation (intervention vs control pharmacy). To monitor the level of non-recruitment, pharmacies in both groups maintained a tally record of customers who declined to join the study and their reasons. Intervention personnel offered their customers the professional anti-smoking counseling. The control group asked customers to register and then continued to provide standard professional support.

The main outcome measures were number of treated smokers, smoking reduction at week 24, and smoking cessation rates at week 24, in accordance with Russell Standard (Clinical) (West et al., 2005). Validation was covered by measuring exhaled carbon monoxide (eCO). Participants who self-reported quit smoking with an eCO concentration of ≤10 ppm at the week 24 follow-up visit were defined as quitters (21). Those smokers who failed to meet these criteria (smoking abstinence and eCO ≤10 ppm) were categorized as smoking cessation failures (i.e. relapsers with eCO ≥10 ppm). Smokers setting a firm quit date was counted as “lost to follow-up” if, on attempting to determine and verify his or her quitter status, he or she could not be contacted. Success rates were measured as the 24-week (24WQ) success rate (West et al., 2005). At each follow-up time point, cigarette consumption was assessed and counseling was offered. Abstinence from smoking was reviewed objectively throughout the study by measuring the levels of eCO at each follow-up visit.

The statistical software SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc., 2007) for Windows was used to store and analyze data, to calculate descriptive statistics, and to demonstrate differences between the intervention and control groups.

Data analysis

We use descriptive statistics (i.e. frequencies/percentages, means/standard deviations) to describe the intervention content (active vs control group). To describe process results in terms of patterns of quitting, we reported the smoking cessation rates. To describe process results in terms of cessation rates, we applied the Fisher test. We used intention-to-treat analysis in the context of analysis of variance (ANOVA) and applied the Wilcoxon/Mann–Whitney test assuming that all those smokers who were lost to follow-up were classified as failures.

Results

All 46 community pharmacies registered at Farmacia OK, a Sicilian Pharmacists’ Association, were invited to participate in the trial; a total of 42 community pharmacies registered in the Farmacia OK database have participated in the trial. In all, 21 pharmacies were randomly allocated by sequential allocation to the intervention group and 21 to the control group; 13 pharmacies of the intervention group completed the study and 8 pharmacies of the control group completed the study. Pharmacies that did not complete the study were contacted by telephone from the principal investigator’s study to know the reasons that prompted them not to complete the project. About 35 percent responded that they had other priorities to follow at that time, 25 percent replied that they did not have enough staff dedicated to the project, 20 percent responded that they did not complete the study for the fear of losing customers in the event of a smoking cessation treatment’s lack of effectiveness, and 20 percent replied that to help smokers takes time and their pharmacy must always be quick and fast so they cannot waste time.

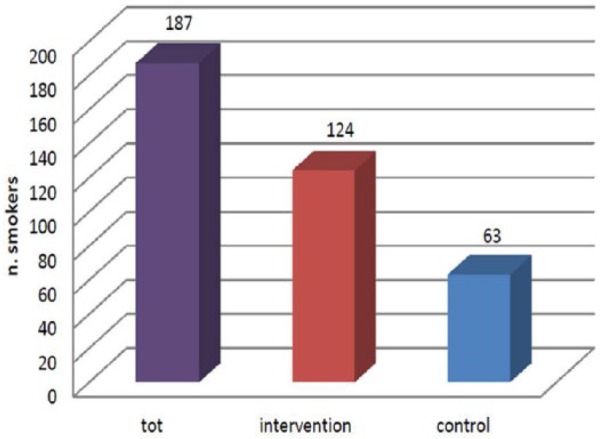

A total of 187 smokers were enrolled in the study (124 smokers were enrolled in the intervention group and 63 smokers were enrolled in the control group; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Numbers of smokers enrolled in the study.

At week 24, we have observed a significant reduction in the number of daily cigarettes smoked between the intervention and control groups. The intervention group smoked a mean of 22.4 cigarettes per day at recruitment versus a mean of 7.5 cigarettes per day at week 24. The control group smoked a mean of 17.3 cigarettes per day at recruitment and 12.5 cigarettes per day at week 24 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Smoking reduction.

Assuming that all those individuals who were lost to follow-up were classified as failures (intention-to-treat analysis), in the context of ANOVA, we applied the Wilcoxon/Mann–Whitney test and showed that the difference between baseline and week 24 between the intervention and control groups resulted statistically significant. In the control group, difference between cigarettes in baseline and week 24 was −0.88 (p = 0.001), while in the intervention group, a reduction in −4.82 (z = −4.028; p = 0.000) was observed.

To valuate cessation rates, we applied the Fisher test and we observed 12.2 percent of smokers quit smoking in the intervention group at week 24, and 1.6 percent of smokers quit smoking in the control group (F = 0.001) (Figure 4). Finally, at week 24, the possibility to quit smoking in the intervention group was 1.48 times greater than the control group (odds ratio = 1.252–1.761).

Figure 4.

Smoking cessation rates at week 24.

Discussion

When a smoker reaches the contemplation stage of smoking cessation, he or she can ask for help from the pharmacists. He or she represents a reference point for his or her ease of accessibility and a reference point for the pharmacist–patient relationship. Customers generally interact with pharmacists often and have great esteem and confidence in pharmacists, and 86.4 percent of pharmacists believe that their profession should become more active in helping patients to quit smoking (Hudmon et al., 2006). Hence, it is very important to have the proper training, to give the right advice to these people who are often not well assisted. In Scotland, Coggans et al. (2000) documented that 66 percent of the surveyed pharmacy patients agreed that they would be willing to discuss tobacco cessation with a community pharmacist. Brewster et al. (2007) surveyed more than 2000 Ontarians, one-third of whom thought that their pharmacist would be a good source of tobacco cessation advice. Also, in one of the two studies conducted in the United States, Hudmon et al. (2003) interviewed NRT users who had either recently quit (75% of respondents) or were about to do so. A majority (63%, n = 103) believed that assistance or advice from a pharmacist would increase the chance of success in quitting. In the other study, of the 73 patients who completed a survey, those who smoked (n = 20) agreed or strongly agreed (85%) that pharmacies were the most convenient places for tobacco cessation programs (Hudmon et al., 2003). Moreover, a majority of smokers believe that community pharmacies are a convenient location for receiving cessation services (Couchenour et al., 2002). Research strongly suggests that pharmacist-led tobacco cessation interventions in community settings are effective. Our study showed higher effectiveness of pharmacists trained in stage-of-change model on smoking cessation and MI to help smokers quit smoking compared to control group. Because of its design, there are a number of limitations that must be considered when interpreting the findings of this study (e.g. the small sample size). Some characteristics of the sample limit generalization of the findings; all participants were regular smokers with an elevated level of nicotine dependence (≥10 cigarettes per day), they were motivated to quit, and all participants were adults and customers of “Farmacia OK group.” Finally, the findings reported from urban Sicilian residents in this study may not be valid for other population samples. Nonetheless, our study indicated that training pharmacists in the stage-of-change model of smoking cessation and MI in a smoking cessation program is an inexpensive strategy that can be quite effective for smokers. This can represent a good starting point for new studies to improve smoking cessation intervention delivered by pharmacists.

Conclusion

This study showed the importance to training pharmacists in the stage-of-change model of smoking cessation and MI. In fact, trained pharmacists have been more effective than non-trained pharmacists in helping people to quit smoking. This can be a good starting point for future studies to build on.

Acknowledgments

Authors wish to thank all participants and pharmacists of SOFAD srl group for their help.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Bond CM, Sinclair HK, Winfield AJ, et al. (1993) Community pharmacists’ attitudes to their advice-giving role and to the deregulation of medicines. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2(1): 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Brewster JM, Victor JC, Ashley MJ. (2007) Views of Ontarians about health professionals’ smoking cessation advice. Canadian Journal of Public Health/Revue Canadienne de Santé Publique 98(5): 395–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coggans N, Johnson I, Mckellar S, et al. (2000) Health promotion in community pharmacy: Perceptions and expectations of consumers and health professionals. Report Commissioned by the Scottish Office, Department of Pharmaceutical Studies, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow. [Google Scholar]

- Cornuz J, Humair JP, Seematter L, et al. (2002) Efficacy of resident training in smoking cessation: A randomized, controlled trial of a program based on application of behavioral theory and practice with standardized patients. Annals of Internal Medicine 136(6): 429–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couchenour RL, Carson DS, Segal AR. (2002) Patients’ views of pharmacists as providers of smoking cessation services. Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association 42(3): 510–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry S, Thompson B, Sexton M, et al. (1989) Psychosocial predictors of outcome in a worksite smoking cessation program. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 5(1): 2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Clemente C. (2001) Scienza della cessazione. Il processo di cambiamento. Italian Heart Journal 2(Suppl. 1): 48–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, et al. (2004) Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ: British Medical Journal 328(7455): 1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton G, Webb B. (1979) Boundary encroachment: Pharmacists in the clinical setting. Sociology of Health & Illness 1(1): 69–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker T, et al. (2008) Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog TA, Blagg CO. (2007) Are most precontemplators contemplating smoking cessation? Assessing the validity of the stages of change. Health Psychology 26(2): 222–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema JE, Hendricks PS. (2010) Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 78(6): 868–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudmon KS, Hemberger KK, Corelli RL, et al. (2003) The pharmacist’s role in smoking cessation counseling: Perceptions of users of nonprescription nicotine replacement therapy. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association 43(5): 573–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudmon KS, Prokhorov AV, Corelli RL. (2006) Tobacco cessation counseling: Pharmacists’ opinions and practices. Patient Education and Counseling 61(1): 152–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HS, Catley D, Harris KJ. (2012) A comparison of autonomous regulation and negative self-evaluative emotions as predictors of smoking behavior change among college students. Journal of Health Psychology 17: 600–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennox AS, Taylor RJ. (1994) Factors associated with outcome in unaided smoking cessation, and a comparison of those who have never tried to stop with those who have. British Journal of General Practice 44(383): 245–250. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightwood JM, Glantz SA. (1997) Short-term economic and health benefits of smoking cessation. Circulation 96(4): 1089–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertinez PJ, Knapp J, Kottke TE. (1993) Beliefs and attitudes of Minnesota pharmacists regarding tobacco sales and smoking cessation counseling. Tobacco Control 2(4): 306–310. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. (2013) Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change (3rd edn). New York: Guilford Press; Available at: https://www.guilford.com [Google Scholar]

- National Audit Office (1992) Community Pharmacies in England. London: HMSO. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts D. (1988) Dispensing by the community pharmacist: An unstoppable decline? The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners 38(317): 563–564. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair HK, Bond CM, Lennox AS, et al. (1995) Nicotine replacement therapies: Smoking cessation outcomes in a pharmacy setting in Scotland. Tobacco Control 4(4): 338–343. [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Inc. (2007) SPSS Base 16.0 User’s Guide. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc., pp. 528–529, 531–532. [Google Scholar]

- Tønnesen P, Carrozzi L, Fagerström KO, et al. (2007) Smoking cessation in patients with respiratory diseases: A high priority, integral component of therapy. European Respiratory Journal 29(2): 390–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health Human Services (1990) The health benefits of smoking cessation. DHHS publication no. (CDC) 90-8516. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Atlanta, USA: Office on Smoking and Health. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health Human Services (2004) The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace-Bell M. (2003) Smoking cessation: The case for hospital-based interventions. Professional Nurse 19(3): 145–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R, Hajek P, Stead L, et al. (2005) Outcome criteria in smoking cessation trials: Proposal for a common standard. Addiction 100(3): 299–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2008) WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic. Available at: http://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/2008/en/index.html

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2009) WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic—Implementing smoke-free environments. Geneva: WHO; Available at: http://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/2009/en/ [Google Scholar]