Abstract

Families of potential post-mortem organ donors face various challenges in the unfamiliar hospital context and after returning home. This review of sources published between 1968 and 2017 seeks to understand their journey as a bereavement experience with a number of unique features. Grief theory was used to identify ways that staff can assist family members to tolerate ambiguities and vulnerabilities while contributing to an environment characterised by compassion and social inclusion. Staff can guide families and create opportunities for meaningful participation, building resilience and developing bereavement-related skills that could assist them in the months that follow.

Keywords: aftercare, bereavement, care, considering organ donation, donation, family centred, family narrative, meaning, organ donation, organ donor, sudden death, tissue

Introduction

Most studies of family experiences in the context of deceased organ donation focus on decision-making and assisting families to make informed decisions. Three reviews have recently consolidated findings to improve understanding of family experiences.

De Groot et al. (2012) highlighted the importance of considering family values and the deceased’s preferences to ensure that families are satisfied with their decision and suggested that moral counselling contributes to confident decisions. Walker et al. (2013) concluded that family members’ comprehension of their in-hospital process relied on supportive information and skilled care contributing to understanding and acceptance of death, which makes the consideration of future perspectives possible. Ralph et al. (2014) reviewed family perspectives and identified themes such as comprehending sudden death, vulnerability, finding meaning, fear and suspicion, decisional conflict, respecting the deceased and needing closure. The need for strategies that assist families to understand death in this context, reduce anxiety, and foster trust was highlighted.

The above-mentioned reviews focus primarily on decision-making (at the time of a sudden bereavement), and Walker et al. (2013) acknowledged that understanding of family experiences is not yet complete. The current review will focus on the family’s bereavement experience (which includes a number of decisions). Where previous studies have identified factors that can be modified to assist with decision-making, this review describes ways that the in-hospital process can contribute meaningfully to the family’s bereavement.

Research questions

“What are the bereavement experiences and bereavement-related needs of families of potential post-mortem organ donors?” and “How should we respond to these needs?”

Aims

This review aims to first illuminate bereavement experiences and needs of families of potential post-mortem organ donors by referring to sources published since 1968, and second, to link findings with grief theory to identify implications for family care. The starting point of this time period, 1968, was chosen as it coincides with the first heart transplant in December 1967 and the official recognition of brain death in 1968.

Method

Data collection

AMED, Embase, MEDLINE, Plumbed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, SocINDEX, and Consumer Health Complete were searched on 4 December 2016. Prior to that various search strategies were tested with the assistance of the university librarian. Forward and backward searching of references and searching through content pages of books related to organ donation was also conducted. The electronic search strategy is described in Supplementary Table 1. In order to return a wide range of sources, no limits were placed on the type of source during the electronic and hand-searching phases.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

English sources published since 1968 referring to family bereavement in the context of a potential organ donation were included. Sources that do not comment on the bereavement of families of potential deceased organ donors were excluded. These excluded sources include those dealing with living organ donation, ways of increasing deceased donation rates, community awareness, and medical aspects of the organ donation context. The search strategy also captured a number of sources that were clearly out of the scope of this review, such as gamete donation, and these were excluded.

This review focusses on development of a narrative about family bereavement, and given that identified sources have contributed to this narrative, no sources were excluded based on factors such as study type or methods.

Results

The first author (S.G.D.), a PhD candidate, conducted the initial screening and selection of sources with the guidance of his supervisory panel. One of the members of the panel has completed a PhD exploring aspects of the experiences of families of potential organ donors, and she was able to provide specific guidance regarding the search and completeness of the final list of selected sources.

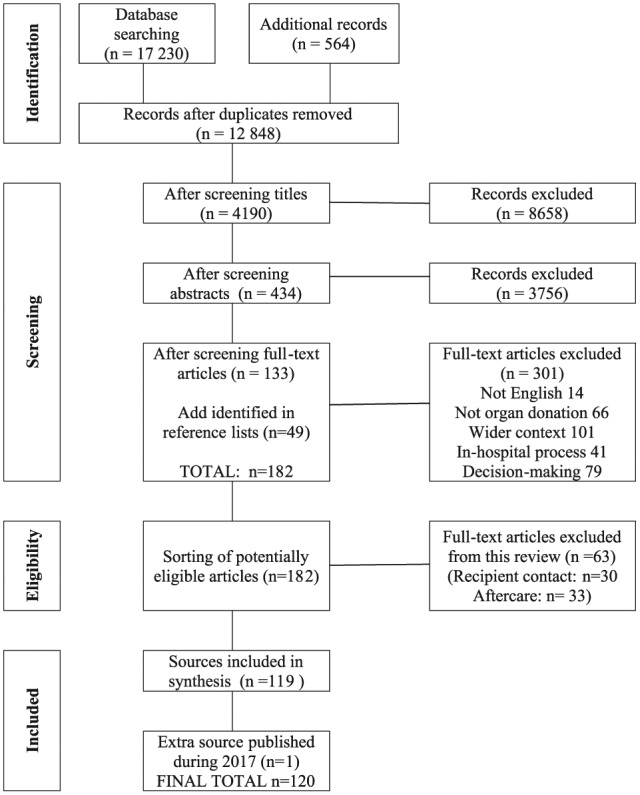

The search identified 12,848 sources (see Figure 1). After screening titles and abstracts, 434 remained and full-text copies were obtained. After evaluating these, 133 sources remained and searching through the references of these sources contributed to identification of a further 49 sources. Full-text copies of these were obtained.

Figure 1.

Selection of sources to be included.

Two sub-categories dealing with (1) relationships between transplant recipients and families who had donated organs (n = 30) and (2) specific aftercare provided to consenting families (n = 33) were identified. These sub-categories are of a different nature to the main group of studies (e.g. ethical debates) and were excluded from the present review, leaving 119 sources. While writing up the review, a relevant article was published (Taylor et al., 2017), and this was added giving a total of 120 sources.

The selected sources included peer-reviewed articles as well as theses (e.g. Ashkenazi, 2010; De Groot et al., 2016a; Jensen, 2011a, 2007; Northam, 2015), critical comments on other articles (e.g. Bauer and Han, 2014), books or chapters in books (e.g. Anker, 2013; Caplan, 1995; Fulton et al., 1977; Holtkamp, 2002, 2000, 1997; Jensen, 2010; Maloney and Wolfelt, 2010; Payne, 2007; Pelletier, 1993b; Sque and Long-Sutehall, 2011), systematic reviews (e.g. Anker, 2013; De Groot et al., 2012; Falomir-Pichastor et al., 2013; Mills and Koulouglioti, 2016; Ralph et al., 2014; Simpkin et al., 2009; Walker et al., 2013), theoretical comments (e.g. Murphy, 2015; Rassin et al., 2005; Youngner et al., 1985), letters to editors (e.g. Corr C and Coolican M, 2010b; Verheijde et al., 2008), reports on commissioned studies (e.g. Sque et al., 2013, 2003), and conference abstracts (e.g. Greser et al., 2013; Kang et al., 2013).

Critical appraisal

This is the first review of family bereavement in the context of the potential for deceased organ donation. For this reason, it was considered important to be as inclusive as our resources allowed us to be, reducing the risk of overlooking valuable information. This was operationalised using a wide time span (1968–2017) and including a wide variety of types of sources as described earlier. This enabled us to gain an understanding of the narrative about family grief as it developed over the last 50 years.

The inclusion of the voices of many researchers and writers in the field adds depth and richness to the descriptions obtained. However, given the diversity of sources, critical appraisal of sources did not seem meaningful. If sources were to be excluded based on their “quality”, voices that have contributed to the narrative of family bereavement would be lost to this review, whereas if all sources were to be included, the evaluation of individual sources would not meaningfully contribute to final outcomes.

It was decided that rather than evaluating the selected sources, we would instead constantly evaluate the narrative that we developed, asking whether it represents the voices of the diverse sources selected in a way that is of use to the reader. The criteria of dependability, credibility, and transferability are described by Porritt et al. (2014) when referring to the evaluation of qualitative sources used in a systematic review. We propose that the same criteria can be used to evaluate the outcome of our review, and that this reflexivity or self-evaluation is a valuable part of our qualitative methodology.

We feel that our study demonstrates dependability in that the emerging narrative reflects the findings of the sources reviewed, and their contributions can be traced by referring to the citations we have made. In a sense this refers to the visibility and logical arrangement of units of the narrative that were provided by previous authors.

Credibility is demonstrated in that the emerging narrative as a whole tells a story that fits with the comments made by individual contributors. In places, this congruence is strengthened by the demonstration that a number of researchers agree with statements made (as if asynchronous member checking had been conducted).

Transferability would imply that the narrative created by weaving together the findings of the various sources not only represents those sources in a dependable and credible way, but would also be useful if applied to the experiences of families encountering the organ donation context in hospitals around the world. If the narrative was transferable, it would assist donation teams and aftercare providers to understand and care for families.

We believe that the narrative that has emerged is transferable, and the addition of insights from grief theory in the latter part of this article will improve understanding of family experiences and enable staff to respond in ways that are well-informed and congruent with current understandings of grief and the organ donation context.

Data extraction

Supplementary Table 2 shows attributes of each source. Most sources were published in peer-reviewed journals, with some being chapters in books, whole books, or reports prepared for government departments. Sources were sorted chronologically to demonstrate how understanding evolved over time before relevant content was extracted.

All sources were viewed as contributing to the narrative of family bereavement, regardless of whether they were reports on quantitative or qualitative studies or theoretical comments. Sources were read thoroughly in their entirety and data that were relevant to the current review were extracted from whichever sections they were found in.

Specifically, data were extracted from sources where family bereavement experiences at the time of a potential organ donation were described, either when authors explicitly referred to grief or when comments could be linked directly to theories of grief (e.g. Neimeyer et al., 2014; Stroebe and Schut, 1999; Walter, 1996; Worden, 2009). For example, some sources described understanding of brain death as being necessary for informed decision-making, without explicitly noting that it is also necessary for acceptance of death, Worden’s (2009) first task of grieving. The extracted data were considered to be valid in the context of the current review because each referred to aspects of the grief and bereavement experiences of families of potential organ donors.

Extracted data were coded for themes and similar data were grouped together to form categories. Although many of the emerging categories could have been predicted before data extraction began (e.g. saying goodbye), we decided to let the categories form as data were extracted. Following this procedure, the categories were constructed to fit the extracted data rather than fitting the extracted data to pre-determined categories. This method is similar to the grounded theory approach described by Sque and Payne (2007). The data extraction itself was conducted by the first author with his supervisory panel being able to provide comments and suggestions as Supplementary Table 3 developed.

Data analysis and synthesis

Extracted data were synthesised creating a narrative which was qualitatively analysed with reference to grief theory contributing to hypotheses about family bereavement and care. In addition to the supplementary data extraction tables, a short video clip is available online summarising the outcome of this review.

The family bereavement experience

Data extracted describes what is known about the bereavement of families of potential post-mortem organ donors. The discussion below portrays the family’s bereavement journey according to categories and themes emerging from the extracted data. It is acknowledged that the order and priority of the features of that journey may differ from family to family. Identified features include pre-existing factors, relationships with staff, in-hospital experiences and needs, anticipatory mourning, coming to terms with death, finding an appropriate response, relationship with the deceased, meaning making and narrative, decision-making, identification of risk and protective factors that influence bereavement, experiences and needs after making a decision, implications for ongoing adjustment, aftercare, contact with recipients, and finally, extended family, friends, and community factors. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed later.

Pre-existing factors

Because factors existing before the in-hospital process (such as the deceased’s role in the family and the family’s composition) influence family bereavement (Gideon and Taylor, 1981), understanding of these factors can assist staff to respond to family needs (Holtkamp, 2002; Pearson et al., 1995; Pittman, 1985). The critical incident leading to the death often contributes to symptoms such as hyper-vigilance, flashbacks, and avoidance of certain stimuli (Fukunishi et al., 2003).

Other pre-existing factors include the family’s support network (Cerney, 1993; Holtkamp, 1997; Payne, 2007), previous experiences of stress and bereavement (Holtkamp, 1997; Pelletier, 1993c), pre-existing strengths and resources (Riley and Coolican, 1999), exposure to awareness campaigns (Rodrigue et al., 2009), attitudes towards donation and inferences about the deceased’s preferences (Falomir-Pichastor et al., 2013).

Relationship with staff

Cleiren and Van Zoelen (2002) argued that it is not information itself that is critical to family well-being, but rather the relational aspect of sharing information. Similarly, Frid et al. (2001) emphasise that staff must be present, listen carefully and allow time for meaningful dialogue. Staff have opportunities to contribute to a memorable and meaningful experience that encourages families to make choices and shape the in-hospital process (Berntzen and Bjork, 2014; Frid et al., 2001; Maloney and Wolfelt, 2010; Neidlinger et al., 2013; Shih et al., 2001a).

The importance of staff training was highlighted (Christopherson and Lunde, 1971; Haney, 1973; Perkins, 1987; Willis and Skelley, 1992), as was the link between staff competence and family satisfaction (Morton and Leonard, 1979; Pelletier, 1993c; Perkins, 1987; Siminoff et al., 2001). Staff are encouraged to develop relationships with family members early (Ashkenazi, 2010; Douglass and Daly, 1995; Fulton et al., 1977; Morton and Leonard, 1979; Painter et al., 1995; Randhawa, 1998; Riley and Coolican, 1999) and continue providing support after the family returns home (Douglass and Daly, 1995; Duckworth et al., 1998; Holtkamp, 1997, 2000; Sque et al., 2003).

Staff members should work together to get to know the family and their needs and then respond in a way that builds trust and shows compassion (Batten and Prottas, 1987; Holtkamp, 2002; La Spina et al., 1993; Perkins, 1987; Rodrigue et al., 2008b; Stouder et al., 2009; Willis and Skelley, 1992) as this impacts positively on bereavement, regardless of the family’s decision about donation (Bellali and Papadatou, 2006; Riley and Coolican, 1999).

The importance of balancing timing and different kinds of support, including emotional, information, and technical care of the patient, was stressed (Corr C and Coolican M, 2010a, 2010b; Forsberg et al., 2014; Jacoby et al., 2005; López Martínez et al., 2008; Macdonald et al., 2008; Merchant et al., 2008a, 2008b; Maloney and Altmaier, 2003; Mills and Koulouglioti, 2016; Ralph et al., 2014; Sque et al., 2005, 2003; Walker and Sque, 2016; Walker et al., 2013).

Staff should link with a family member or family friend who is less emotionally impacted by the event (Gideon and Taylor, 1981; Sque et al., 2003). This person could clarify matters for other family members, encourage anticipatory mourning, contribute to shared decisions, and foster family ownership of the process (López Martínez et al., 2008). Falomir-Pichastor et al. (2013) emphasised the value of social inclusion and researchers agreed that family and friends are important sources of support (Manuel et al., 2010; Shih et al., 2001b; Stouder et al., 2009). Others highlighted the value of providing a neutral intermediary linking family and staff, while focussing on the family’s bereavement needs and answering their questions (Gideon and Taylor, 1981; Hart, 1986; Jacoby et al., 2005; Lloyd-Williams et al., 2009; Morton and Leonard, 1979; Payne, 2007; Pittman, 1985; Rassin et al., 2005; Willis and Skelley, 1992).

The in-hospital process has an influence on staff too. They should analyse their own feelings, fears, and values before they can effectively respond to families (Hart, 1986; Pearson et al., 1995; Perkins, 1987; Riley and Coolican, 1999), and Duckworth et al. (1998) suggest that opportunities for support should be available to staff.

In-hospital experiences and needs

Many studies focus on support that assists with decision-making (De Groot et al., 2012), while promoting family satisfaction is less prominent in training and assessment of outcomes (Marck et al., 2016). Staff should adapt their actions to suit the family - creating opportunities for emotional expression when that is lacking, or sharing techniques (such as mindfulness) when emotions are excessive (López Martínez et al., 2008; Perkins, 1987).

Dealing with the critical incident and in-hospital process is challenging for individuals and the family system (Gideon and Taylor, 1981; Pelletier, 1993b, 1993c; Pittman, 1985; Willis and Skelley, 1992). Walker and Sque (2016) noted that symptoms of shock, disbelief, denial, guilt, feeling lost, fear, helplessness, devastation and confusion are to be expected. Families must be provided with opportunities to participate actively in the in-hospital process (including aspects of patient care, family care, and responding to options and choices that become available) to reduce feelings of aimlessness and helplessness while developing hope (Pelletier, 1993c; Randhawa, 1998; Riley and Coolican, 1999).

Meeting family needs for adequate time and ongoing information (Pelletier, 1993b; Perkins, 1987) must start when the family enters the hospital and continue regardless of the family’s decision about donation (Holtkamp, 1997).

Anticipatory mourning

Pelletier (1993c) reports that realising the threat to their relative’s life contributes to stress, helplessness, sadness, numbness, and panic. Information should be provided gradually with numerous meetings preparing families for the impending death (Holtkamp, 1997; Simpkin et al., 2009). Some researchers identified the potential for a brief period of anticipatory mourning at this time (Haney, 1973; Hart, 1986; Steed and Wager, 1998; Youngner et al., 1985) where families could engage in meaning-making activities such as managing environmental demands, spending time with and away from the patient, adapting to new roles and responsibilities, saying good-bye and developing a post-death psychological bond (Holtkamp, 2000). Sque and Long-Sutehall (2011) agreed that this would assist families to construct their relative’s biography and family narrative of their experience. Time with their dying relative and support from compassionate staff contributes to trust and lays the foundation for hope which is expected to transform from hope for the patient’s survival to hope for a peaceful death and (for consenting families) hope for successful transplants (Jensen, 2011a, 2011b; Northam, 2015).

Coming to terms with death

Medical advancement contributed to a situation where new attitudes and practices concerning death and dying were necessary (Christopherson and Lunde, 1971; Fulton et al., 1977; Morton and Leonard, 1979; Simmons et al., 1972). Haney (1973) recognised the importance of seeing technology in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) as a feature of the family’s bereavement that could enable signs of death to be redefined, avoiding false hope. Families and staff actively introduce, comprehend, and interpret the context, transforming an unusual death experience into something understandable (Hadders and Alnaes, 2013; Jensen, 2011a, 2011b).

Researchers suggested that concrete information should be presented in different forms and repeated until it is understood (Berntzen and Bjork, 2014; Cerney, 1993; Frid et al., 2001; Gideon and Taylor, 1981; Jacoby et al., 2005; Long et al., 2008a, 2006; Macdonald et al., 2008; Mills and Koulouglioti, 2016; Pearson et al., 1995; Smudla et al., 2012; Soriano-Pacheco et al., 1999; Sque et al., 2005; Steed and Wager, 1998; Willis and Skelley, 1992) because many families find it difficult to accept death in the face of apparent life (Pittman, 1985; Youngner et al., 1985), resulting in stress and ambivalence (Rassin et al., 2005). Youngner et al. (1985) pointed out that families and staff experience “emotional discomfort and cognitive dissonance” (p. 323).

Internal dialogue while recalling time spent with their relative assists families to come to terms with information about death (Long et al., 2006). Many families reconcile features of the experience by concluding that life without brain function is not the life they want for their relative (Long et al., 2006) and some consent to donation hoping that the delay between consent and surgery would provide one last chance for recovery (Manuel et al., 2010; Rassin et al., 2005). Knowing the time of death is important to families (Fulton et al., 1977; Holtkamp, 1997; Northam, 2015), and Taylor et al. (2017) found that when families had consented to donation after cardiac death (DCD) and their relative did not die within the required timeframe, some family members questioned whether they had given up too soon.

Some researchers developed frameworks capturing aspects of the family’s experience. Sque and Payne (1996) developed a Theory of Dissonant Loss, demonstrating the interaction between variables encountered as families attempt to resolve ambiguities and make sense of their experience. Long et al. (2008a, 2008b) argued that ambivalence contributes to emotional and cognitive conflict and proposed that clarity can be reached through a process of rationalisation enabling the family to shift from hope for recovery to acceptance of death.

Manuel et al. (2010) described families’ attempts to create a sense of peace while struggling to acknowledge death, needing a positive outcome, creating a living memory, buying time, and utilising support networks. Similarly, Frid et al. (2007) described an unfolding process characterised by chaotic unreality, inner collapse, sense of forlornness, clinging to hope for survival, reconciliation with the reality of death and receiving care that brings comfort. Kesselring et al. (2007) described the stages of realising something was wrong, receiving bad news, brain death and donation request, decision-making, and saying good-bye.

Finding an appropriate response to the situation

Researchers highlighted the importance of active participation and argued that staff should show families that there is a wide range of possible responses, empowering them to create a meaningful experience (Frid et al., 2007; Maloney and Wolfelt, 2010; Shih et al., 2001a; Thomas et al., 2009). Observing brain death testing is helpful for some families (De Groot et al., 2012; Walker et al., 2013), and staff should ensure that language and actions provide a congruent message (Hadders and Alnaes, 2013; Rassin et al., 2005).

The donation pathway – donation after brain-death (DBD) or donation after circulatory death (DCD) – and other factors impact on the family’s experience of the last moments with their relative (Hoover et al., 2014; Murphy, 2015). Although Ashkenazi and Cohen (2015) found that parents donating after DBD were more satisfied with the separation from their child than parents where the DCD pathway was followed, no differences were found in later adjustment (Ashkenazi and Guttman, 2016). Marck et al. (2016) feels that families consenting to DCD need to be well prepared for the short timeframes and possibility that organ donation may not proceed, in which case some are comforted when tissue donation is possible (Marck et al., 2016; Walker and Sque, 2016).

When staff perceived DCD or death of a child to be more difficult than DBD or the death of an adult, they provided more care (Siminoff et al., 2015, 2017). In contrast, Sque et al. (2013) found that needs reported were similar in these different situations, reinforcing Siminoff et al.’s (2015) argument that all families should receive the same quality of care.

When families consent, they begin to incorporate the potential for organ donation into their meaning making and if donation does not proceed, they may experience disappointment, inability to honour their family member, and impaired ability to make sense of the tragedy, suggesting a disruption of sense-making and benefit finding efforts (Taylor et al., 2017).

Upon reflection, staff participating in Taylor et al.’s (2017) study accepted that by focussing on the potential for donation, they had raised family members’ hope and perhaps contributed to later disappointment when donation did not proceed.

Rodrigue et al. (2010) found that some family members who knew their relative’s preferences and had being exposed to awareness campaigns initiated organ donation discussions. These families should be seen as having special needs and their understanding must be carefully assessed. Staff should answer questions, provide emotional support, and contribute to a positive experience for the family whether donation is possible or not (Rodrigue et al., 2010).

Relationship with the deceased

Researchers observed that families often expressed their decision in terms of their desire to follow the deceased’s preferences (Christopherson and Lunde, 1971; Fulton et al., 1977; Haney, 1973; Morton and Leonard, 1979; Pelletier, 1993c; Perkins, 1987), suggesting an ongoing connection. Walter (1996) described the need to create durable biography for the deceased, incorporating aspects of their previous relationships into family life (Bellali and Papadatou, 2006; Payne, 2007; Sque and Payne, 1996).

Some consenting families appreciate being offered the opportunity to view the donor’s body after surgery (Perkins, 1987), and those who accept the offer should be well prepared for the experience beforehand (Douglass and Daly, 1995; Holtkamp, 1997; Shih et al., 2001b).

Meaning-making and narrative

Meaning-making efforts of consenting families often include organ donation giving meaning to an otherwise meaningless death (Bartucci and Bishop, 1987; Batten and Prottas, 1987; Fulton et al., 1977; Hart, 1986). Consenting families make meaning related to helping others, doing what their relative wanted, or finding something positive in a devastating event (Bauer and Han, 2014; Christopherson and Lunde, 1971; Morton and Leonard, 1979; Pearson et al., 1995; Pelletier, 1993cc). Families who decline may create meaning based on protecting the body (Sque et al., 2006; Sque and Long-Sutehall, 2011), allowing the deceased to rest in peace, protecting the family from uncertainty and perceived suffering (Northam, 2015), or believing that it was not spiritually appropriate to consent to donation (Pearson et al., 1995).

Pittman (1985) argues that the family’s attempt to make sense of the request for organ donation requires input in the form of clear information from a trustworthy source enabling them to tell the story of the death over and over again until it fits comfortably with them. To create a realistic and durable biography of the deceased’s life, family members need to speak freely to each other, challenging and supplementing ideas (Sque et al., 2003). Staff can assist by facilitating a supportive environment (Mills and Koulouglioti, 2016) in which families feel comfortable talking about life and death so that shared narratives emerge, contributing to reassurance and reducing anxiety (Jensen, 2007; Manuel et al., 2010; Payne, 2007). The value of an interested conversational partner and continuity of care should not be underestimated (Frid et al., 2001).

Bellali and Papadatou (2006) observed the commencement of meaning making when parents accepted brain death and described themes such as the life and death of their child, the impact of a decision about donation on their grieving experience, coping with the loss and suffering, perception of their own identity and availability of social support.

When constructing the story of their relative’s death, family members oscillate between maintaining hope while searching for meaning and feeling hopeless and lacking meaning (Frid et al., 2007; Walker and Sque, 2016). The central metaphor identified in Frid et al.’s (2007) study reflects the theories of Dissonant Loss (Sque and Payne, 1996) and Conflict Rationalisation (Long et al., 2008a, 2008b): In the anteroom of death, families are unprepared and confront a number of ambiguities contributing to confusion and suffering, which must be endured for the family to find a satisfactory way forward.

Jensen (2010) found that stories of families who consented to donation acknowledged their loss and also contained a sense of presence linked to the ongoing survival of their relative’s organs, showing that narratives depict human relationships in ways that principles and theories cannot (Kinjo and Morioka, 2011). Northam (2015) argued that when family members realise that their relative will not survive, they begin to hope for the family’s future without the deceased. Jensen (2016) agreed about the value of hope, arguing that hope enabled families to create meaningful and worthy deaths in the midst of suffering.

Findings highlighted the importance of respecting the deceased, honouring their wishes (Ralph et al., 2014) and preserving their body (Sque and Long-Sutehall, 2011). Consenting families seem to balance respecting the dignity of the deceased, and allowing their body to be used to save others by transforming hope for survival to hope for successful donation, and linking dignity to the legacy and personality of the deceased rather than to their body (Jensen, 2016).

Decision-making

The family’s primary experience is the loss of their relative and the question about donation is secondary or peripheral (Hoover et al., 2014; Maloney and Wolfelt, 2010; Satoh, 2011). Nevertheless, decision-making is part of the experience and is explored below.

Families appreciate an informative and sensitive approach that is appropriately timed, presented by compassionate and knowledgeable staff, in a private and informal setting (Perkins, 1987). An appropriately timed request occurs when the family is ready (De Groot et al., 2012) and is linked to the family’s understanding of their relative’s death or impending death (Anker, 2013; Walker et al., 2013).

Researchers acknowledge that making a decision about donation is not easy (Bartucci, 1987; Hart, 1986) and may contribute to ambiguity, ambivalence and dissonance (Robertson-Malt, 1998; Youngner et al., 1985). Family disagreements do occur, prompting families to decide in a way that fits with the family hierarchy (Haney, 1973) and/or different family roles. Northam (2015), for example, found that mothers played an important role in decision-making. Factors that contribute to difficulty include the appearance of life, ambiguity about the time of death, a special attitude towards specific body parts (Fulton et al., 1977), a concern that consenting would impact on patient care (Morton and Leonard, 1979) and a need to protect the deceased’s body (Pittman, 1985; Sque and Long-Sutehall, 2011).

Families in Christopherson and Lunde’s (1971) study felt that it was important that both their pain and their desire to help others was acknowledged. Fulton et al. (1977) confirmed that in addition to the family’s desire to help others, consenting to donation contributed to a sense of finality and was accompanied by anxiety. Youngner et al. (1985) noted that the excitement in the media and donation campaigns denied the family’s suffering and some families argued that the gift of life narrative neglected the pain of their grief (Holtkamp, 1997; Siminoff and Chillag, 1999; Youngner et al., 1985) leaving their voice absent from representations of organ donation (Robertson-Malt, 1998).

Youngner et al. (1985) felt that such concerns should be made transparent so that appropriate responses could be found. La Spina et al. (1993) considered this situation and concluded that families who consent to donation are able to simultaneously “… act out of generosity … and a willingness to sacrifice” (p. 1700). Sque et al. (2006) agreed that representing donation as a gift of life did not acknowledge the emotional and cognitive struggle when family members consider donation as a gift and a sacrifice (Sque and Galasinski, 2013).

Frid et al. (2007) felt that continua of presence–absence and divisibility–indivisibility were relevant in that the deceased seems present with signs of life, but is dead, and the idea of the person and their body are on some level indivisible, but for donation to take place, the person and the body need to be seen as separate. Sque et al. (2008) observed that consenting families let go of the need to protect their relative’s body by developing an ongoing psychological relationship.

When making their decision, family members support and encourage each other (Shih et al., 2001b) and active involvement contributes to a decision that is meaningful to them and the deceased (Holtkamp, 2002; Sque et al., 2003). It has been found that when the preferences of the deceased were unknown, families had a more difficult time making a decision, and those who then refused donation often attributed their decision to external factors such as inadequate support (De Groot et al., 2016b; López Martínez et al., 2008).

Bellali and Papadatou (2007) found that on an individual level, either a quick reactive decision or a carefully considered one was made, while on a family level, decisions may be reached by consensus, by accommodating various views or be imposed on family members by other members. Shih et al. (2001a) agree that it is important to understand how family and friends contribute together to the final decision.

Ralph et al. (2014) argue that a family-centred approach must acknowledge both the needs of individual family members and family dynamics. When family members have opposing views, those in favour of donation usually back down (López Martínez et al., 2008) and when there is significant disagreement, decision-making takes longer, families remain somewhat uncertain of their final decision (Falomir-Pichastor et al., 2013; Jacoby and Jaccard, 2010; Morton and Leonard, 1979; Pittman, 1985; Rodrigue et al., 2008b; Walker et al., 2013) and there is increased risk of difficulties later (Holtkamp, 2002).

The relationship between the values of the relatives and the preferences of the deceased should be explored. Where these factors are not aligned, confusion, disagreement, and later regret can be expected (Anker, 2013; Marck et al., 2016; Mills and Koulouglioti, 2016; Northam, 2015), whereas moral counselling can lead to stable decisions (De Groot et al., 2012).

Many families reported that although the process was difficult, they appreciated being able to make the decision themselves (Willis and Skelley, 1992). Those who were committed to their reasons felt that the requester had not influenced them (Batten and Prottas, 1987).

Identification of factors contributing to risk of complications in bereavement

It is important to identify family members who are at risk for complicated bereavement (Shih et al., 2001a) so that early referral to counselling services can be facilitated (Gideon and Taylor, 1981). Families experiencing ambivalence are at greater risk for adverse effects (Morton and Leonard, 1979) and when families feel that time with the deceased was unnecessarily restricted, they may experience mistrust and bitterness (Holtkamp, 1997; Northam, 2015).

When consenting families seek their relative in the recipients or receive insufficient information about transplant outcomes, there is a risk of increased stress (Bellali and Papadatou, 2006; Christopherson and Lunde, 1971; Pittman, 1985).

Being unable to ascertain their family member’s preferences or having false hope (Haney, 1973) could contribute to anxiety and uncertainty (Youngner et al., 1985). For both consenting and declining families, meanings associated with guilt, bitterness, injustice and blame contribute to depressed mood and suicidal thoughts (Bellali and Papadatou, 2006; Gideon and Taylor, 1981).

Sanner (1994) found that when families value helping others and understand the value of donation on one hand and on the other hand are uncertain about the diagnosis of brain death, want to protect their relative, experience distrust and anxiety, or feel that the limits of nature or God should be respected, decision-making is especially difficult.

Problems during the in-hospital process have been found to contribute to bad memories, family stress (Pearson et al., 1995), confusion and complicated bereavement (Holtkamp, 1997; Smudla et al., 2012). Regret is more common when family members later understand aspects of the in-hospital process that would have contributed to another decision, when family members backed down during decision-making (Bellali and Papadatou, 2006), when the first discussion was with a non-donation specialist before death had occurred, when family members had not had a previous discussion about donation or when they did not remember any awareness campaigns (Rodrigue et al., 2006, 2008a).

Ambivalence or regret has also been found to be related to poor communication from staff at crucial times (Fulton et al., 1977) and other problems experienced during the in-hospital process (Bartucci, 1987). Ambivalence in turn may contribute to uncertainty, depression (Cleiren and Van Zoelen, 2002), complications in bereavement and post-traumatic stress disorder (Ashkenazi, 2010; De Groot et al., 2012, 2016a, 2016b; Kesselring et al., 2007; Mills and Koulouglioti, 2016; Morton and Leonard, 1979; Verheijde et al., 2008; Yousefi et al., 2014).

Rodrigue et al. (2008a) found that regret or uncertainty about the decision contributed to distress and intrusive thoughts, while De Groot et al. (2012) argued that when relatives do not follow the deceased’s preferences, it is more likely that the grief process would be adversely affected. Cleiren and Van Zoelen (2002) argued that while behaviours such as crying, outbursts, disbelief or anger are not pathological, numbness may indicate misunderstanding and information should be repeated. Sque et al. (2003) found that isolated people are at more risk, as are spouses who become single parents as a result of the death.

Identification of protective factors that may assist the bereaved to cope with their loss

Families who engage in the process and face their grief display a wider range of emotions and have been found to accept death and cope with other demands better than those who withdraw (La Spina et al., 1993). Support from family, friends, religion, and culture are significant factors that assist families during their bereavement (Kim et al., 2013; Stouder et al., 2009).

Pelletier (1993b) added that identifying something positive in the situation, remaining connected to the deceased, alternating between withdrawing and actively engaging in a problem-solving way, searching for useful information and seeking emotional support contributed to coping. The success of the in-hospital process should be reflected in the family’s ability to make a decision with which they were later satisfied (Sque et al., 2006) and staff members’ ability to assist families in their bereavement (Bellali et al., 2007).

Experiences and needs after making a decision

The importance of providing ongoing care and keeping the family up to date with regard to arrangements after they have made their decision was highlighted (Bellali et al., 2007; Cleiren and Van Zoelen, 2002; Fulton et al., 1977; Lloyd-Williams et al., 2009; Morton and Leonard, 1979; Pelletier, 1993b; Shih et al., 2001a; Steed and Wager, 1998). Jensen (2011b) found that some consenting families appreciated the opportunity to say goodbye after the organs were removed. This seemed to contribute to emotional closure, assisting the grief process by allowing a more traditional parting (Berntzen and Bjork, 2014; Forsberg et al., 2014; Frid et al., 2001; Jacoby et al., 2005) which fosters adjustment to loss (Ashkenazi and Cohen, 2015).

Researchers found that most families are satisfied with their decisions (Bartucci, 1987; Batten and Prottas, 1987; Greser et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2014; Marck et al., 2016; Redelmeier et al., 2014; Rodrigue et al., 2008a; Tymstra et al., 1992; Walker and Sque, 2016; Walker et al., 2013), but have also noted that family well-being has only been superficially studied and little is known about long-term adjustment of families of potential organ donors (Ashkenazi and Cohen, 2015; Bellali and Papadatou, 2006; Caplan, 1995; Riley and Coolican, 1999; Smudla et al., 2012).

Implications of in-hospital experiences for ongoing adjustment to loss

Christopherson and Lunde (1971) found that acute grief did not last longer than suggested by theory, and Fulton et al. (1977) found that 18 months after the death, families focussed on their loss rather than the decision about donation suggesting that grieving was not changed by the in-hospital experience.

Consenting and declining families experience similar levels of depression, suggesting that it is not the decision (Cleiren and Van Zoelen, 2002; Sque et al., 2003; Tavakoli et al., 2008) but going home without the deceased that is the source of the family’s pain (Holtkamp, 2002), and Shih et al. (2001b) found that the impact of the in-hospital process depends on social, cultural, spiritual and legal factors.

Researchers found it difficult to recruit families who had declined donation, and much of what is known reflects the experiences of consenting families. In that regard, it was generally found that when families had been treated with care and respect in the hospital and had access to follow-up services, grieving was not complicated (Ashkenazi and Cohen, 2015; Batten and Prottas, 1987; Painter et al., 1995; Pearson et al., 1995; Perkins, 1987; Steed and Wager, 1998; Tymstra et al., 1992).

However, Frid et al. (2001) pointed out that adjustment is ongoing, and Sque et al. (2003) found that after a year, families focused more on unanswered questions related to the in-hospital experience than 3–5 months after the death. Thomas et al. (2009) found that consenting families continued to ask questions such as “What happened to the organs?” and felt that given the technical, unusual death experience, ongoing support was needed.

Aftercare

Christopherson and Lunde (1971) reported that families required assistance initially but later did not appear to need help. However, others feel that considering organ donation is not part of normal grieving and introduces new aspects to the death and bereavement experiences of families (Haney, 1973; Holtkamp, 2002; Pittman, 1985; Sque et al., 2003; Youngner et al., 1985).

Families who consented to donation were found to have needs for further information, recognition, acknowledgement, gratitude, reassurance and bereavement counselling (Fulton et al., 1977; Pittman, 1985; Ralph et al., 2014). Researchers concluded that ongoing family support should be the cornerstone of any organ donation programme (Gideon and Taylor, 1981; Kang et al., 2013; Morton and Leonard, 1979; Pittman, 1985) and suggested that a long-term specialised approach is required, where care is neutral rather than attached to the hospital (Jensen, 2011b; Pelletier, 1993c; Pittman, 1985; Sque and Long-Sutehall, 2011).

The hospital, donation agency and organisation providing support should have a close working relationship so that families having questions about their experience can be assisted (Sque et al., 2003) regardless of their decision. Bereavement support should begin at the bedside and continue until it is no longer needed (Bellali et al., 2007; Riley and Coolican, 1999; Sque et al., 2003). The bereavement needs of each family are expected to be different and support must be flexible and tailored to fit family requirements (Cerney, 1993; Douglass and Daly, 1995; Holtkamp, 1997; Painter et al., 1995; Payne, 2007; Pelletier, 1992, 1993c; Soriano-Pacheco et al., 1999; Steed and Wager, 1998).

Holtkamp (2002) feels that the support provider should sensitively understand and respond to the family’s unique circumstances, be genuinely moved by the family’s narrative, and be able to cope with the intensity of emotion. Knowledge of the organ donation context is important, and the aftercare support coordinator must serve as a family advocate rather than promote the donation agency or organ donation (Holtkamp, 2002). Given that families are likely to require various forms of support, the coordinator should have access to others able to provide social work, financial or legal advice (Kim et al., 2014; Shih et al., 2001b) and participate in the development of policies and procedures (Holtkamp, 1997). Payne (2007) agrees that needs are diverse and support should include practical assistance with tasks related to the death such as the funeral and meeting others who have had a similar experience.

Berntzen and Bjork (2014) argued that research on bereavement programmes was scarce and is required to improve quality of care for families (Forsberg et al., 2014; Marck et al., 2016). While the donation agency has a responsibility to ensure that families have access to support, Jensen (2010) argues that consultation with families is vital because the organisation should not own the programme or structure it according to their assumptions while believing that families would agree with methods and terminology used.

Contact with recipients after consenting to donation

A number of sources discouraged over-identification with recipients, believing that it may complicate grieving (Christopherson and Lunde, 1971; Holtkamp, 1997; La Spina et al., 1993; Pittman, 1985). Fulton et al. (1977) reported that recipients were not encouraged to write letters to donor families. However, Robertson-Malt (1998) questioned the appropriateness of laws and actions that decided for families and recipients that they may not have contact, arguing that this denies the way that their lives have become connected and silences their voices.

Christopherson and Lunde (1971) mention that in two cases, recipients and donor family members expressed a mutual desire to meet. This was facilitated and the meeting was meaningful for both parties, neither of whom requested any further meetings. Research since then indicates that many consenting families are interested in the recipients’ ongoing health and find it comforting to know that transplants were successful (Fulton et al., 1977; Gideon and Taylor, 1981; Holtkamp, 1997; Morton and Leonard, 1979; Painter et al., 1995; Pelletier, 1993a; Steed and Wager, 1998; Willis and Skelley, 1992; Youngner et al., 1985). Some researchers feel that the biographies of the donor, their family and the recipients overlap, with information about recipients’ progress contributing to the family’s ongoing narrative (Jensen, 2011a; Shih et al., 2001b; Sque and Long-Sutehall, 2011).

The Transplant Games gives recipients the opportunity to celebrate their health and give thanks, while donor families get the opportunity to see the difference that transplantation makes (Jensen, 2007) and Services of Remembrance provide a social context for the unique grief of donor families where hearing recipient stories and seeing their gratitude provides social affirmation and comfort (Murphy, 2015).

Extended family, friends and community

The first organ donations and transplants took place within a society that had no previous experience of such events. There was much interest and curiosity, and the media took every opportunity to create a news story, until donor families and recipients made it known that they found this intrusive and requested anonymity (Christopherson and Lunde, 1971). However, many families who had consented to donation found that making their decision known to family and friends at the funeral was comforting and generally contributed to positive reaction. In some cases though, differences in opinion and attitude towards donation contributed to long-lasting rifts and complications in bereavement (Fulton et al., 1977).

Some families reported uncertainty about letting others know about their decision (Northam, 2015; Steed and Wager, 1998; Tymstra et al., 1992) and network members sometimes struggled to find an appropriate response (Robertson-Malt, 1998; Steed and Wager, 1998). Nevertheless, Greser et al. (2013) found that most families communicated their decision to family and friends after returning home and received a positive reaction.

Grief theory and implications for family care

The previous section described features of the bereavement journey of families of potential organ donors and now themes connecting those experiences to grief theory are explored. The questions asked here are “What themes are highlighted by the data extracted?”, “How do these relate to current theories of grief?” and “What are the implications for the care of families of potential organ donors?”

Theoretical synthesis

Stroebe and Schut’s (1999) Dual Process Model (DPM) describes a process whereby the bereaved engage in loss-oriented activities related to coming to terms with the death (such as saying good-bye) and restoration-oriented activities related to changes brought about by the loss (such as becoming a single parent). The DPM describes movement between these types of activities as oscillation which assists the bereaved to balance and regulate emotion. This theory is relevant in the hospital where the bereaved oscillate between factors such as the death of their relative and the donation request (Pelletier, 1993b), while viewing the potential for donation in terms of a gift and a sacrifice (Sque et al., 2006).

Bellali and Papadatou (2006) observed that family members regulate their responses to loss and decision-making at an individual and interpersonal level. This fits with Stroebe and Schut’s (2015) discussion of family-level grieving. Stroebe and Schut (2016) introduced the concept of overload to their model, acknowledging that the bereaved sometimes perceive the demands of their situation to be excessive contributing to anxiety, stuckness and other symptoms. Stroebe and Schut (2016) suggest that at this time, openness allows the bereaved to share their sense of overload with others, contributing to a more effective response from their support network. In the hospital with family members close by and trained staff providing support, the bereaved can be assisted to engage in oscillation and use openness to facilitate social inclusion.

Vulnerability and resilience

Content analysis of the narrative presented earlier contributed to an overarching continuum of needing to tolerate vulnerability while building resilience. Here, the term vulnerability is used to describe anxiety, uncertainty and dissonance experienced by families when encountering a sudden death, the confusing diagnosis of brain death or understanding the DCD procedure (Ralph et al., 2014). These factors are not seen as risk factors, but common features of this in-hospital context. Risk factors are viewed as being related to reactions to the vulnerability and include ambivalence, mistrust, guilt, misunderstanding, blame and isolation.

Assisting family members to respond to features of the environment such as the presence of supportive staff, family and friends, and an opportunity to say good-bye activates protective factors such as facing grief, expressing emotion, finding something

positive, developing a psychological bond, and making a confident decision.

Relating this to Stroebe and Schut’s (2015, 1999) theory, when families experience care and social inclusion in the hospital (Falomir-Pichastor et al., 2013), they can be assisted to engage in oscillation while in this supportive environment. Utilising family resources, staff can assist them to tolerate vulnerability (Frid et al., 2007) and increase their capacity to respond in a way that builds resilience. This may reduce the risk of overload, enabling families to avoid quick, reactive decisions that they may later regret and providing them with bereavement-related skills to facilitate a healthy start to their grieving.

Family narrative

Family bereavement can also be understood in terms of meaning making, narrative (Neimeyer et al., 2014) and the development of a durable biography of the deceased (Walter, 1996). Oscillation between loss orientation and restoration orientation, as well as tolerance of vulnerability and building of resilience, is seen as providing content for the narrative both in terms of understanding gained (e.g. clarity regarding brain death) and process involved (e.g. working together with staff and family members would contribute to a narrative characterised by social inclusion).

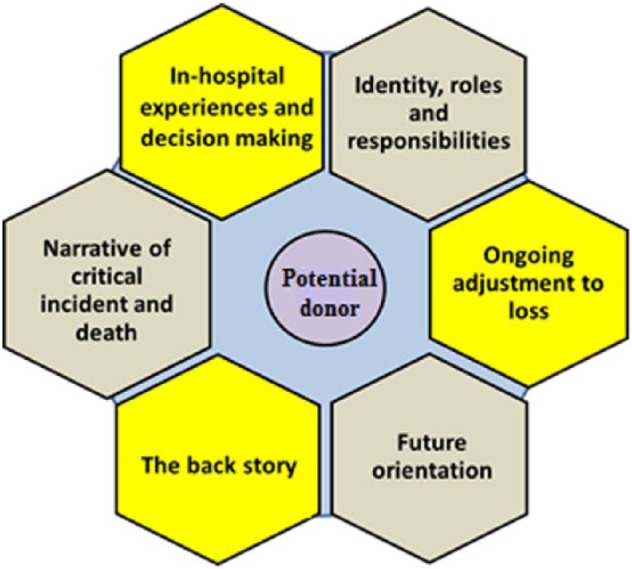

To simplify the discussion of meaning making and narrative, an optimistic description is presented below while we acknowledge that each of the factors referred to such as acceptance of death, in-hospital care, opportunities for participation or meanings made are not always experienced in this ideal way. Six key elements of family narrative are highlighted by data extracted from sources: the back story; the critical incident and story of the death; the donation decision, roles and responsibilities; ongoing adjustment to loss and future orientation. These are described as follows.

The back story

When family members spend time in the hospital, the sharing of memories can facilitate the development of a durable biography of the deceased’s life with the family. Aspects of this biography may assist the family when they encounter tasks such as making a decision about donation that fits with the deceased and themselves. By providing a private space, and asking about the deceased, staff can assist the family to accept their loss, share memories, and experience the pain of grief together.

The critical incident and story of the death

Deaths that contribute to the potential for organ donation are often as a result of unexpected and traumatic events. Some family members may have witnessed or being involved in the event (e.g. passengers in a motor vehicle accident). In addition, unfamiliar in-hospital processes can contribute to cognitive dissonance and ambivalence. In this context, family-centred care contributes to a supportive environment in which family members can come to terms with their relative’s unfamiliar death.

Meanings made in the hospital and social inclusion experienced at the start of their bereavement may provide a model for healthy bereavement experiences including creating opportunities for further meaning making, and recognition of the value of oscillating between tasks focused on the death and their loss and other tasks related to adjusting to life. The in-hospital process itself will also become part of the family’s narrative of the death (Ashkenazi, 2010).

The donation decision

One of the first tasks that family members encounter after a death in this context is the request to make a decision about organ donation. With assistance from staff, they can face this task and decide in a way that is congruent with family values and the deceased’s preferences, a process that may facilitate the development of an ongoing psychological bond with the deceased. The task offers opportunities for family members to show respect for each other and the deceased while aiming to make a shared decision.

Identity, roles and responsibilities

The identity of the deceased and their role in the family will be explored as the family develops a durable biography and family narrative. Family members will also get the opportunity to experience new roles while observing their resources and vulnerabilities. Staff can assist by adjusting the intensity of the tasks that family members engage in.

Ongoing adjustment to loss

Support from friends and family has been identified as an important factor influencing adjustment to loss, as has religion and culture (Stouder et al., 2009). Some families may make use of existing support networks while coming to terms with their loss and others may utilise aftercare services provided by the organ donation organisation. Coping mechanisms that family members found helpful during the in-hospital process may be used to manage stress and facilitate togetherness in the months that follow.

Future orientation

Walker et al. (2013) highlighted the value of future considerations and others have highlighted the value of hope (Jensen, 2011a, 2011b, 2016; Northam, 2015; Walker and Sque, 2016) which is a future-oriented concept. Family members may at various points during the in-hospital process ask themselves, “How will we cope with this?” With support from family, friends and staff, initial answers may be found to that question, and this may provide hope when the question is asked in a future context.

Some features of the in-hospital process, such as understanding brain death, tolerating ambiguity and making a decision about donation, have been found to be very challenging while others, such as having family around and receiving family-centred care, have been described as comforting. When the comforting features outweigh the challenging ones, and families have been able to accept death and make a confident decision regarding organ donation, the experience of overcoming the challenge together may contribute to hope for the family’s future.

The features described above are in constant interaction with each other, continually developing and changing over time. The potential donor is placed in the centre of the model depicted in Figure 2 to symbolise the way that meanings made need to show congruence with each other and with the family’s memories of the deceased. When the meaning making and narrative processes start at the hospital with guidance from staff, it may be easier for families to actively use similar strategies in the months that follow.

Figure 2.

Features of meaning making and narrative.

Meaning of loss codebook

Gillies et al. (2014) developed a codebook to guide recognition of meaning made during bereavement. A number of the codes identified in the codebook reflect features of family bereavement described earlier, including family bonds, valuing relationships, compassion (including helping others), memories, spending time together, affirmation of the deceased, spirituality, identity as a bereaved person, regret, lack of understanding and identity change.

In the specific context of the potential for organ donation, the current review highlights four additional themes: living on in others (in a physical sense), continuing to save others (living with a transplant includes the continued working of the transplanted organ as opposed to a single event of saving another person), keeping the body whole and protecting the body. These meanings are reflected in the gift and sacrifice metaphors.

Implications for the provision of support

Staff who assist families through the in-hospital process and the months thereafter have opportunities to facilitate engagement in activities contributing to tolerance of vulnerability and building of resilience. The tasks may have a blend of loss orientation and restoration orientation. For example, during tasks related to anticipatory mourning, family members confront their loss and experience their vulnerabilities while making suggestions, adapting to new roles and participating actively, potentially contributing to confidence. Staff can encourage engagement while also being alert to the risk of overload and intervening when appropriate by adjusting the demands of the tasks, suggesting switching to other tasks or providing opportunities for openness, social inclusion and hope.

Creating opportunities for family members to share memories and thoughts can contribute to a meaningful experience and a shared narrative. Meanings made can be monitored, with the need for intervention being indicated by the emergence of meanings such as guilt and blame.

Strengths of this review

The review consolidates 50 years of findings related to the bereavement of families of potential organ donors. A concise introduction and understanding of the area is provided, and this will be a valuable resource for critical care and donation agency staff as well as General Practitioners and others offering support to the bereaved. For researchers, it provides a foundation from which to explore bereavement in this context, identifying studies that present detailed discussions of particular features of interest. The descriptions of opportunities for support underpinned by grief theory could be usefully incorporated into professional development programmes for nursing and other staff working in the in-hospital context as well as those providing aftercare. The review is published in an open-access journal allowing any interested party to explore the proposed framework.

The interplay between tolerance of vulnerability and building resilience is compatible with discussions of hope and despair (Northam, 2015; Walker and Sque, 2016), Dissonant Loss (Sque and Payne, 1996) and Conflict Rationalisation (Long et al., 2008b) while the idea of narrative is compatible with the metaphor of the family journey (Forsberg et al., 2014; Frid et al., 2001, 2007). The inclusion of elements of the DPM is compatible with findings of Pelletier (1992, 1993a, 1993c) who described families alternating focus between the death and in-hospital tasks and Duckworth et al. (1998) who argued that a bereavement service should assist families to come to terms with the death and reorienting themselves to life without the deceased.

Limitations

Only English sources were used, and many of these focus more on the experiences of families who consented to donation than on experiences of those who declined. There is also more focus in the literature on families encountering DBD rather than DCD. Few studies focused specifically on bereavement, and the proposed framework needs to be debated and tested for relevance.

Conclusion

This review described the bereavement of families of potential donors by presenting a narrative of their bereavement journey based on identified sources and then relating findings to theories of grief and bereavement. Consolidating understanding in this way highlights leverage points where hospital staff and aftercare support coordinators can offer assistance and guidance.

Future research should seek to verify the validity of the proposed model and develop methods of identifying risk and protective factors, while exploring the selection of outcome measures to be used to guide bereavement-focussed care. The in-hospital process is rich with opportunities for assisting families as they encounter the first tasks of their bereavement. The potential contribution of social support, togetherness and inclusion when assisting families to find meaning in their experience and develop healthy bereavement practices should be explored to its fullest. Death also has an impact on work, school, religious, social and geographic communities, and the ripple effect of events at the hospital should receive more attention.

Acknowledgments

SGD, a PhD candidate, conducted the literature search and compiled a draft of the review with guidance from his supervisory panel. Supervisors evaluated the draft and critically reviewed the methods, process, outcomes and presentation. In this way, all authors contributed to the final article. DB and FvH provided equal guidance and contribution. The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their time and thoughtful comments.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: SGD acknowledges that as a PhD candidate, support was received through an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

References

- Anker A. (2013) Critical conversations: Organ procurement coordinators’ interpersonal communication during donation requests In: Laurie MA. (ed.) Organ Donation and Transplantation. New York: Nova Science Publishers, pp. 189–221. [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazi T. (2010) The ramifications of child organ and tissue donations in the mourning process and parents’ adjustment to loss: A comparative study of parents choosing to donate organs and those choosing not to donate. PhD Thesis, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv. [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazi T, Cohen J. (2015) Interactions between health care personnel and parents approached for organ and/or tissue donation: Influences on parents’ adjustment to loss. Progress in Transplantation 25(2): 124–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazi T, Guttman N. (2016) Organ and tissue donor parents’ positive psychological adjustment to grief and bereavement: Practical and ethical implications. Bereavement Care 35(2): 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Bartucci MR. (1987) Organ donation: A study of the donor family perspective. The Journal of Neuroscience Nursing 19(6): 305–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartucci MR, Bishop PR. (1987) The meaning of organ donation to donor families. American Nephrology Nurses’ Association Journal 15(6): 369–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batten HL, Prottas JM. (1987) Kind strangers: The families of organ donors. Health Affairs 6(2): 35–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer P, Han Y. (2014) Parental perspectives of donation after circulatory determination of death in children: Have we really investigated the heart of the matter? Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 15(2): 171–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellali T, Papadatou D. (2006) Parental grief following the brain death of a child: Does consent or refusal to organ donation affect their grief? Death Studies 30(10): 883–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellali T, Papadatou D. (2007) The decision-making process of parents regarding organ donation of their brain dead child: A Greek study. Social Science & Medicine 64(2): 439–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellali T, Papazoglou I, Papadatou D. (2007) Empirically based recommendations to support parents facing the dilemma of paediatric cadaver organ donation. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing 23(4): 216–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntzen H, Bjork IT. (2014) Experiences of donor families after consenting to organ donation: A qualitative study. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing 30(5): 266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan AL. (1995) The telltale heart: Public policy and the utilization of non-heart-beating donors In: Arnold RM, Youngner SJ, Schapiro MPH, et al. (eds) Procuring Organs for Transplant: The Debate Over Non-heart-beating Cadaver Protocols. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 207–218. [Google Scholar]

- Cerney MS. (1993) Solving the organ donor shortage by meeting the bereaved family’s needs. Critical Care Nurse 13(1): 32–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopherson LK, Lunde DT. (1971) Heart transplant donors and their families. Seminars in Psychiatry 3(1): 26–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleiren MP, Van Zoelen AA. (2002) Post-mortem organ donation and grief: A study of consent, refusal and well-being in bereavement. Death Studies 26(10): 837–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corr C, Coolican M. (2010. a) Understanding bereavement, grief, and mourning: Implications for donation and transplant professionals. Progress in Transplantation 20(2): 169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corr C, Coolican M. (2010. b) Understanding bereavement, grief, and mourning. Progress in Transplantation 20(2): 112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot J, van Hoek M, Hoedemaekers C, et al. (2016. a) Decision making by relatives of eligible brain dead organ donors. PhD Thesis, Radboud University, Nijmegen: Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/2066/159498 (accessed 10 December 2016). [Google Scholar]

- De Groot J, van Hoek M, Hoedemaekers C, et al. (2016. b) Request for organ donation without donor registration: A qualitative study of the perspectives of bereaved relatives. BMC Medical Ethics 17(1): 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot J, Vernooij-Dassen M, Hoedemaekers C, et al. (2012) Decision making by relatives about brain death organ donation: An integrative review. Transplantation 93(12): 1196–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot J, van Hoek M, Hoedemaekers C, et al. (2015) Decision making on organ donation: The dilemmas of relatives of potential brain dead donors. BMC Medical Ethics 16(1): 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglass GE, Daly M. (1995) Donor families’ experience of organ donation. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care 23(1): 96–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth RM, Sproat GW, Morien M, et al. (1998) Acute bereavement services and routine referral as a mechanism to increase donation. Journal of Transplant Coordination 8(1): 16–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falomir-Pichastor JM, Berent JA, Pereira A. (2013) Social psychological factors of post-mortem organ donation: A theoretical review of determinants and promotion strategies. Health Psychology Review 7(2): 202–247. [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg A, Floden A, Lennerling A, et al. (2014) The core of after death care in relation to organ donation – A grounded theory study. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing 30(5): 275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frid I, Bergbom I, Haljamäe H. (2001) No going back: Narratives by close relatives of the braindead patient. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing 17(5): 263–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frid I, Haljamäe H, Öhlén J, et al. (2007) Brain death: Close relatives’ use of imagery as a descriptor of experience. Journal of Advanced Nursing 58(1): 63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunishi I, Kita Y, Paris W, et al. (2003) Relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder and emotional conditions in families of the cadaveric donor population. Transplantation Proceedings 35(1): 295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton J, Fulton R, Simmons R. (1977) The cadaver donor and the gift of life In: Simmons R, Marine S, Simmons R. (eds) Gift of Life. the Social and Psychological Impact of Organ Transplantation. New York: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 338–376. [Google Scholar]

- Gideon MD, Taylor PB. (1981) Kidney donation: Care of the cadaver donor’s family. Journal of Neurosurgical Nursing 13(5): 248–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillies J, Neimeyer RA, Milman E. (2014) The meaning of loss codebook: Construction of a system for analyzing meanings made in bereavement. Death Studies 38(1–5): 207–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greser A, Grammenos D, Schuller LH, et al. (2013) Communication of the decision in favour of organ donation through donor families and the reactions within the circle of family and friends. Transplant International 26: 73. [Google Scholar]

- Hadders H, Alnaes AH. (2013) Enacting death: Contested practices in the organ donation clinic. Nursing Inquiry 20(3): 245–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney CA. (1973) Issues and considerations in requesting an anatomical gift. Social Science & Medicine 7(8): 635–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart D. (1986) Helping the family of the potential organ donor: Crisis intervention and decision making. Journal of Emergency Nursing 12(4): 210–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtkamp SC. (1997) The donor family experience: Sudden loss, brain death, organ donation, grief and recovery In: Chapman J, Deiherhoi M, Wight C. (eds) Organ and Tissue Donation for Transplantation. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 304–322. [Google Scholar]

- Holtkamp SC. (2000) Anticipatory mourning and organ donation In: Rando TA. (ed.) Clinical Dimensions of Anticipatory Mourning: Theory and Practice in Working with the Dying, Their Loved Ones and Their Care Givers. Champaign, IL: Research Press, pp. 511–536. [Google Scholar]

- Holtkamp SC. (2002) Wrapped in Mourning: The Gift of Life and the Donor Family Trauma. New York: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover S, Bratton S, Roach E, et al. (2014) Parental experiences and recommendations in donation after circulatory determination of death. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 15(2): 105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby L, Jaccard J. (2010) Perceived support among families deciding about organ donation for their loved ones: Donor vs nondonor next of kin. American Journal of Critical Care 19(5): e52–e61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby LH, Breitkopf CR, Pease EA. (2005) A qualitative examination of the needs of families faced with the option of organ donation. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing 24(4): 183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AM. (2007) Those who give and grieve. Master’s Thesis, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AMB. (2010) A sense of absence: The staging of heroic deaths and ongoing lives among American organ donor families In: Bille M, Hastrup F, Soerensen TF. (eds) An Anthropology of Absence: Materializations of Transcendence and Loss. New York: Springer; pp. 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AMB. (2011. a) Orchestrating an exceptional death: Donor family experiences and organ donation in Denmark. PhD Thesis, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AMB. (2011. b) Searching for meaningful aftermaths: Donor family experiences and expressions in New York and Denmark. Sites: A Journal of Social Anthropology and Cultural Studies 8(1): 129–148. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AMB. (2016) Make sure somebody will survive from this: Transformative practices of hope among Danish organ donor families. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 30(3): 378–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang M, Yoon S, Kim G, et al. (2013) Providing support to donor families: Evaluation and challenges. Transplantation 96(10): S197. [Google Scholar]

- Kesselring A, Kainz M, Kiss A. (2007) Traumatic memories of relatives regarding brain death, request for organ donation and interactions with professionals in the ICU. American Journal of Transplantation 7(1): 211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Yoo YS, Cho OH. (2014) Satisfaction with the organ donation process of brain dead donors’ families in Korea. Transplantation Proceedings 46(10): 3253–3256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinjo T, Morioka M. (2011) Narrative responsibility and moral dilemma: A case study of a family’s decision about a brain-dead daughter. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics 32(2): 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Spina F, Sedda L, Pizzi C, et al. (1993) Donor families’ attitude toward organ donation. The North Italy transplant program. Transplantation Proceedings 25(1): 1699–1701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Williams M, Morton J, Peters S. (2009) The end-of-life care experiences of relatives of brain dead intensive care patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 37(4): 659–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long T, Sque M, Addington-Hall J. (2008. a) What does a diagnosis of brain death mean to family members approached about organ donation? A review of the literature. Progress in Transplantation 18(2): 118–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long T, Sque M, Addington-Hall J. (2008. b) Conflict rationalisation: How family members cope with a diagnosis of brain stem death. Social Science & Medicine 67(2): 253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long T, Sque M, Payne S. (2006) Information sharing: Its impact on donor and nondonor families’ experiences in the hospital. Progress in Transplantation 16(2): 144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López Martínez JS, Martín López MJ, Scandroglio B, et al. (2008) Family perception of the process of organ donation. Qualitative psychosocial analysis of the subjective interpretation of donor and nondonor families. The Spanish Journal of Psychology 11(1): 125–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald ME, Liben S, Carnevale FA, et al. (2008) Signs of life and signs of death: Brain death and other mixed messages at the end of life. Journal of Child Health Care 12(2): 92–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney R, Altmaier EM. (2003) Caring for bereaved families: Self-efficacy in the donation request process. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings 10(4): 251–258. [Google Scholar]

- Maloney R, Wolfelt A. (2010) Caring for Donor Families: Before, during and after (2nd edn). Fort Collins, CO: Companion Press. [Google Scholar]

- Manuel A, Solberg S, MacDonald S. (2010) Organ donor experiences of family members. Nephrology Nursing Journal 37(3): 229–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marck CH, Neate SL, Skinner M, et al. (2016) Potential donor families’ experiences of organ and tissue donation-related communication, processes and outcome. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care 44(1): 99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant SJ, Cheung E, Yoshida EM. (2008. a) Exploring the psychological effects of deceased organ donation on the families of the organ donors: A response. Clinical Transplantation 22(5): 687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]