Abstract

The development of novel culture systems that mimic the in vivo microenvironment may be beneficial for inducing the differentiation of stem cells and promoting liver function. In the present study, spheroid cultures and decellularized liver scaffolds (DLSs) were utilized to obtain differentiated hepatocyte-like cells. Mouse bone marrow (BM)-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) self-aggregated into spheroids under low-attachment conditions and implanted into the DLSs via a negative pressure suction device. The Albp-ZsGreen adenoviral vector was utilized for real-time monitoring of hepatocyte-like cell differentiation. To detect the differentiation stages of the MSCs, immunostaining of hepatocyte markers and functional analysis was performed. Compared with traditional 2D monolayer induction, mouse BM-MSCs spheroids and DLSs in 3D culture generated greater yields of mature, differentiated hepatocytes. In conclusion, this 3D culture system may provide a strategy for generating hepatocyte-like cells for portable liver micro-organs, and aid clinical hepatocyte transplantation and liver tissue engineering.

Keywords: mesenchymal stem cell, spheroid, decellularized liver scaffolds, hepatic differentiation

Introduction

Liver transplantation is the primary treatment for patients with acute liver failure, end-stage liver disease and inherited liver-based metabolic disorders. However, the demand for suitable organs for transplantation far exceeds the available donor organs (1). Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine-based strategies are a promising alternative to organ transplantation (2–4).

Tissue-specific cells and scaffolding biomaterials are essential for liver tissue engineering (5). As primary hepatocytes exhibit poor proliferative potential in vitro, it may be more feasible to generate hepatocytes via the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). MSCs are commonly cultured as 2D monolayers using conventional tissue culture techniques, which may result over time in loss of replicative ability, reduced colony-forming efficiency and poor differentiation capacity (6,7). The microenvironment has a crucial influence on stem cell biology. Therefore, the present study investigated spheroid culture, which has been reported to improve cell-cell contact and interactions of cells with the extracellular matrix (ECM) compared with traditional monolayer methods (8). As cells exist in their native morphology, significant differences in phenotype and responses have been observed between monolayer and spheroid cultures (9,10). Our previous study revealed that 3D spheroid cultures of MSCs enhanced cell yield and maintained stemness, in addition to osteogenetic and adipogenetic differentiation efficiencies (11).

In the last decade, advances in organ and tissue decellularization have made it possible to obtain tissue-specific ECM from whole organs via the perfusion of the organs with various detergents (12–15). Whole organ decellularization represents a potential strategy for the fabrication of scaffolds for the engineering of tissues and organs, as the decellularized scaffolds maintain their microarchitecture and retain numerous bioactive signals that are difficult to replicate artificially (16). Decellularized liver scaffolds may act as anchors for hepatocyte-like cells derived from stem cells, and aid their attachment, proliferation and organization (17–19). In addition, decellularized liver scaffolds may be an alternative option for heterotopic hepatocyte transplantation (20).

In the present study, spheroid culture and decellularized liver scaffolds (DLSs) were utilized to establish a novel 3D culture system to promote maturation of hepatocyte-like cells from mouse bone marrow (BM)-derived MSCs. The Albp-ZsGreen adenoviral vector, which is driven by the albumin (ALB) promoter, was utilized for real-time monitoring of the differentiation status of hepatocytes from stem cells. The findings of the present study may be useful for cell transplantation purposes.

Materials and methods

Animals

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sichuan University (Chengdu, China). Three livers were isolated from 6-month-old male Bama miniature pigs weighing 10–15 kg for perfusion decellularization. Male C57BL/6 mice (n=3; age, 8 weeks; weight, 20–25 g) were used for hepatocyte isolation. All animals were obtained from the Animal Experiment Center of Sichuan University (Chengdu, China). The mice and Bama miniature pigs were maintained on an alternating 12-h light/dark cycle, fed regular chow, and given water ad libitum.

The surgeries were performed under ketamine (6 mg/kg body weight, administered intramuscular; Kelun, Chengdu, China) and xylazine (10 mg/kg intramuscular; Kelun) anesthesia. Under deep anesthesia, a laparotomy was performed and the liver was exposed. After systemic heparinization through the inferior vena cava, the hepatogastric ligament was carefully dissected. The proximal PV was catheterized. The hepatic artery and common bile duct were ligated and transected. All perihepatic ligaments were severed. Simultaneously, the liver was slowly perfused with 2 l deionized water containing 0.1% EDTA (Kelun) through a cannula in the PV, and the SHIVC was transected, allowing outflow of the perfusate. Following blanching, the liver was stored at −80°C overnight. The Bama miniature pigs were sacrificed during the perfusion process due to an excessive amount of blood loss.

Cultivation of mouse BM-MSCs

Commercial mouse BM-MSCs were purchased from Cyagen Biosciences Inc. (Guangzhou, China). C57BL/6 mouse MSC growth medium (cat. no. MUBMX-90011; Cyagen Biosciences Inc.) was utilized to culture cells and was replaced at least every 2 days. Cells at passage 4–6 were used for subsequent experiments.

Formation of BM-MSCs spheroids

For spheroid cultures, the harvested BM-MSCs were suspended in 10 ml serum-free medium at 1×106 cells/ml and cultured in glass spheroid dishes (13×8×4 cm), which were coated with Sigmacote® (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Spheroid dishes were incubated with continuous rocking at 0.167 Hz for 24 h to induce spheroid formation. BM-MSC spheroids were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA). The viability of BM-MSC spheroids was assessed using the FluoroQuench™ fluorescent stain (One Lambda; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Samples were imaged using a Leica DFC495 fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany).

Evaluation of decellularized porcine liver

DLSs were obtained as previously described (21). DLS samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and 2.5% glutaraldehyde, prior to observation under a scanning electron microscope (22).

Cell seeding and hepatic differentiation

Two culturing methods for differentiation [single cell (2D) and spheroids + DLS (3D)] were studied. DLSs were incubated in culture medium at 37°C overnight. Following aspiration of the medium, 100 µl cell suspension of harvested BM-MSC spheroids was pipetted onto the center of the DLS via a negative pressure suction device. Spheroids were allowed to settle and attach to the scaffold for 4 h. Subsequently, 2 ml medium of stage one was added slowly to the spheroids. To induce hepatic differentiation, serum-free Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (HyClone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with growth factors was utilized, as described previously (23): i) 10 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and 20 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF) for 2 days; ii) 20 ng/ml hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), 10 mg/ml bFGF, and 0.61 mg/m; nicotinamide (NAM) for 7 days; and iii) insulin transferrin selenium (ITS) premix solution (10 µg/ml insulin, 5.5 µg/ml transferrin, 5 ng/ml selenium), 1 µmol/l dexamethasone (DXM) sodium phosphate, and 20 ng/l oncostatin M (OSM) for 14 days. Supplements were all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA. The culture medium was replaced every 3 days during the differentiation period.

Albp-ZsGreen adenovirus transduction

To monitor the differentiation of hepatocytes from BM-MSCs, the Albp-ZsGreen adenoviral vector containing the ALB promoter was designed and constructed as previously described (24). 2D and 3D hepatocyte-like cells (1×106 cells/well) were incubated with the Albp-ZsGreen adenoviral vector (10 µl; 1×108 plaque formation units; multiplicity of infection, 100) in 6-well tissue culture plates for 2 h prior to examining ALB expression at 48 h using a Leica DM40000B microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH). Following DAPI staining, the percentage of ZsGreen-positive cells was determined using ImageJ software version 1.48 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Three samples of both 2D and 3D undifferented cells were incubated with adenovirus as controls.

Western blot analysis

Differentiated cells in 2D and 3D culture systems were homogenized to generate protein lysates using radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China) with protease inhibitors (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Equal quantities of protein (80 µg) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Membranes were blocked in 5–10% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated overnight with anti-ALB (1:1,000; rabbit monoclonal; cat. no. ab207327; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and anti-GAPDH (1:8,000; mouse monoclonal; cat. no. MAB374-AF647; EMD Millipore) primary antibodies at 4°C. Following this, the membranes were washed twice with TBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (cat. no. ab6721; 1:1,000) and goat anti-mouse (cat. no. ab6789; 1:1,000) secondary antibodies (both from Abcam) for 2 h at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized using an enhanced ehemiluminescence kit (Thermo Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

ALB and urea production

Conditioned media from the differentiated BM-MSCs of 2D and 3D culture systems was collected on day 21 and ALB levels were measured using a mouse ALB ELISA kit (cat. no. E90-134; Bethyl Laboratories, Inc., Montgomery, TX, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. A total of 2 mM heavy, diazonium-enriched ammonium chloride (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc., Tewksbury, MA, USA) was added to the medium to determine the metabolic ability of differentiated cells. The total urea concentration and proportion of diazonium-enriched urea and natural urea in the medium were measured to determine the source of urea synthesis. Supernatants were quantified by capillary gas chromatography and mass spectrometry, as previously reported (25). Freshly isolated mouse primary hepatocytes were included as a control. Hepatocytes were isolated using a two-step perfusion method as previously described (25).

Immunofluorescence analysis

Differentiated cells from 2D and 3D groups were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min at room temperature. Following permeabilization, samples were blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) in PBS (blocking buffer) for 1 h and subsequently treated with primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. The antibodies utilized were sheep anti-ALB (1:1,000; cat. no. ab8940; Abcam), rabbit anti-α-fetoprotein (1:1,000; AFP; cat. no. AF5134; Affinity Biosciences, Cell Signal Transduction, Cambridge, UK) and rabbit anti-cytokeratin-19 (CK19; 1:1,000; cat. no. AF0192; Affinity Biosceinces, Cell Signal Transduction). Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated rabbit anti-sheep (1:400; cat. no. ab150181; Abcam) and goat anti-rabbit (1:400; cat. no. ab150077; Abcam) secondary antibodies were incubated with samples at room temperature for 1 h in the dark. Following nuclear staining with DAPI, slides were mounted and observed under a Leica DMI6000 fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH).

Gene array analysis

Sample labeling and array hybridization were performed with Whole Mouse Genome Oligo Microarray (cat. no. G4122F; 4×44K; Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Briefly, total RNA was extracted from BM-MSCs, primary mouse hepatocytes and 3D hepatocyte-like cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and used for synthesis of cRNAs, which were labeled with Cyanine 3-UTP. The concentration of cRNA was measured using a NanoDrop ND-1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA). The hybridized arrays were performed and scanned using the Agilent DNA Microarray Scanner (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Data were normalized and analyzed using the TIGR MultiExperiment Viewer version 4.8.1 (Institute of Genomic Research, Rockville, MD, USA). Gene ontology (GO) analysis was performed using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID; https://david.ncifcrf.gov) to determine the functions of the predicted target genes and to uncover the miRNA-target gene regulatory network based on the predicted biological processes and molecular functions; P<0.01 was used as the threshold.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of three independent experiments. Data were analyzed using SPSS software version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A one-way analysis of variance followed by the Dunnett's post hoc test was performed to compare groups. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Characterization of BM-MSC spheroids

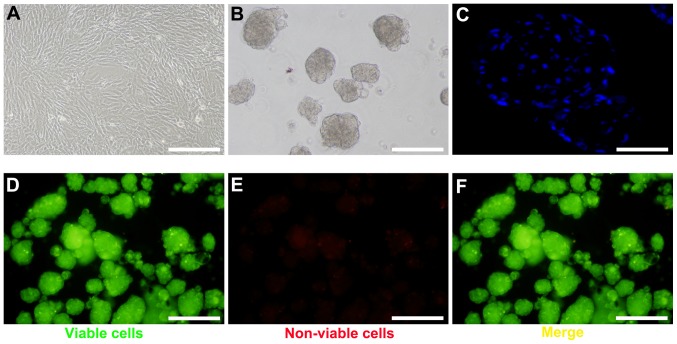

To generate BM-MSC spheroids, BM-MSCs were harvested at passage 4–6 (Fig. 1A). Following optimization of cell number and growth conditions, spheroid formation was observed under a scanning electron microscope within 24 h (Fig. 1B). Based on DAPI staining, the cells within the spheroids were in close proximity (Fig. 1C). The FluoroQuench™ fluorescent staining assay revealed that the viability of BM-MSCs in spheroids remained >95% in 3D culture (Fig. 1D-F).

Figure 1.

2D and 3D culture of mouse BM-MSCs. (A) BM-MSCs in traditional monolayer culture. (B) Formation of spheroids following 24 h of rocking culture. (C) DAPI staining of spheroids. (D) Green staining of viable spheroids, (E) red staining of non-viable spheroids and (F) merged image of viable and non-viable spheroids, as determined by FluoroQuench™ staining. Scale bars, 200 µm. BM-MSCs, bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells.

Characterization of DLSs

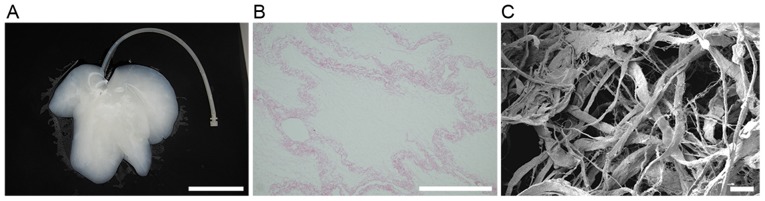

Whole-organ decellularization was achieved by portal perfusion using sodium dodecyl sulfate and Triton X-100. Following decellularization, the porcine liver parenchyma became semi-transparent (Fig. 2A). Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed no visible cell nuclei and cellular material in the decellularized liver scaffolds (Fig. 2B). Decellularized tissue sections were observed under a scanning electron microscope to determine whether the structure of the bio-scaffold was preserved (Fig. 2C). Reticular collagen fibers, which provide support for the hepatic tissue, were evident.

Figure 2.

Whole-organ porcine liver decellularization. Representative images of (A) liver tissue (scale bar, 10 cm), (B) hematoxylin and eosin staining of DLS (scale bar, 100 µm) and (C) scanning electron microscope analysis of DLS structure (scale bar, 20 µm). DLS, decellularized liver scaffold.

Identification of hepatocyte-like cells

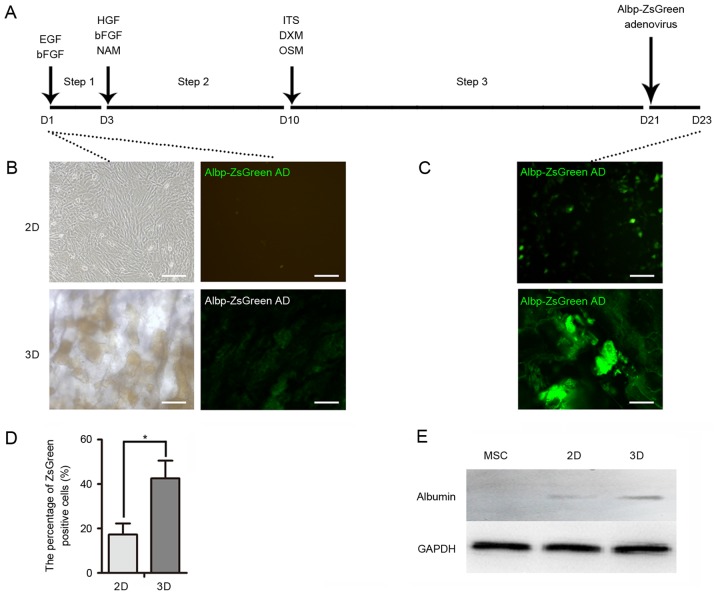

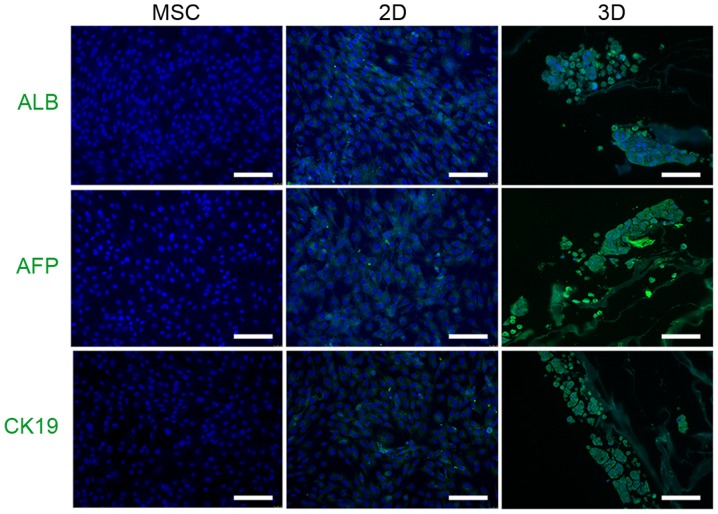

The hepatocyte-like cells were generated from mouse BM-MSCs as shown in Fig. 3A. The expression of the Albp-ZsGreen adenovirus was not observed in non-hepatic cells (Fig. 3B); however, ALB synthesis was observed in mature hepatocytes, which suggested that hepatic differentiation had occurred in 2D and 3D cells (Fig. 3C). A greater percentage of ZsGreen-positive cells was observed in the 3D group, which suggested that the 3D culture system provided an improved external microenvironment for differentiation (Fig. 3D). Similarly, the expression levels of ALB in 3D cells were greater compared with the 2D cells following induction (Fig. 3E). In addition, immunocytochemistry demonstrated that 3D cells expressed hepatocyte-like cell markers, including ALB, AFP and CK19, to a greater extent than 2D cells (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Hepatocyte-like cell induction. (A) Timeline of hepatic induction of mouse MSCs for 2D and 3D cultures. Cells were incubated in medium containing various growth factors for 23 days. Albp-ZsGreen adenovirus was added to induce expression of ALB. (B) Green fluorescence of Albp-ZsGreen adenovirus indicated ALB synthesis in non-hepatic or (C) hepatic differentiated MSCs. (D) Percentage of Albp-ZsGreen-positive hepatocyte-like cells in each group. (E) Western blot analysis demonstrated the expression of ALB in undifferentiated MSCs and following hepatic differentiation using 2D or 3D models. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. *P<0.05. Scale bars, 100 µm. MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; ALB, albumin; EGF, epidermal growth factor; bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; NAM, nicotinamide; DXM, dextromethorphan; OSM, oncostatin M; ITS, insulin transferrin selenium.

Figure 4.

Analysis of hepatic protein markers in mouse MSCs following 23 days of hepatic differentiation. Green immunofluorescence staining of ALB, AFP and CK19 in undifferentiated MSC control, 2D and 3D groups. Nuclei were stained blue with DAPI. Scale bars, 100 µm. MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; ALB, albumin; AFP, α-fetoprotein; CK19, cytokeratin-19.

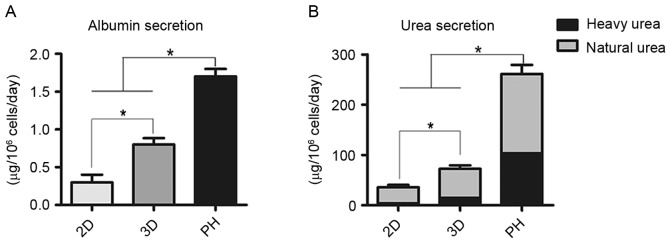

Metabolic activity of differentiated cells in 2D or 3D culture

Compared with the 2D group, cumulative ALB secretion by differentiated cells in the 3D group was significantly greater compared with the 2D group (P<0.05; Fig. 5A). Clearance of heavy urea, which contained ammonium chloride, was greater in the 3D group compared with the 2D group (P<0.05; Fig. 5B). The proportion of heavy urea to total urea produced by the 2D group, 3D group and primary hepatocytes fluctuated from 9.6 to 11.8%, 19.8 to 22.1% and 39.8 to 42.1%, respectively (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Hepatic function analysis in mouse mesenchymal stem cells following 3 weeks of hepatic differentiation. (A) Albumin and (B) urea secretion following 3 weeks hepatic differentiation in the 2D and 3D groups and in the primary hepatocyte control group. Scale bars, 100 µm. *P<0.05. PH, primary hepatocytes.

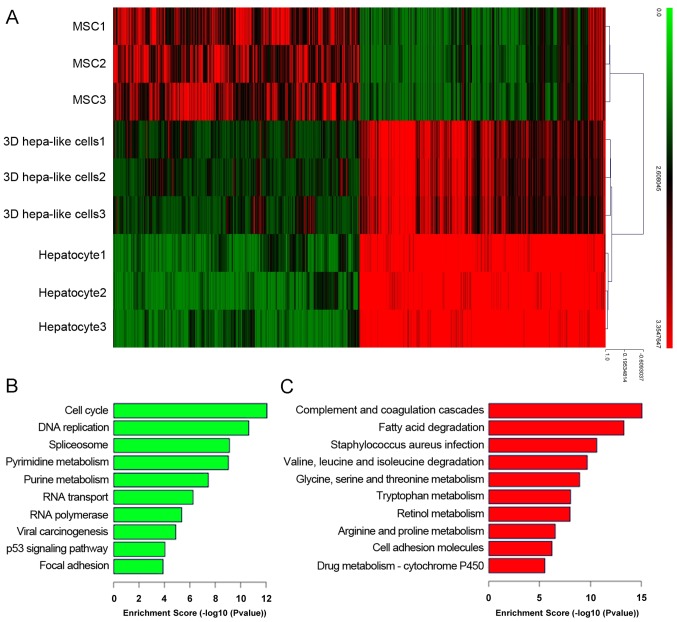

Gene expression in 3D hepatocyte-like cells

The results of the present study demonstrated the advantage of 3D culture in promoting hepatic differentiation of mouse BM-MSCs. The cDNA microarray showed that differentiated 3D hepatocyte-like cells resembled mouse primary hepatocytes more than mouse BM-MSCs (Fig. 6A). GO enrichment analysis revealed that signaling pathways that associated with liver function were significantly upregulated, including those involved in fat metabolism, amino acid metabolism and drug metabolism (Fig. 6C), whereas signaling pathways associated with the cell cycle were significant downregulated in the 3D group compared with BM-MSCs (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

GO analysis of gene expression arrays. (A) Gene expression profile analysis of undifferented BM-MSCs, 3D hepatocyte-like cells and primary mice hepatocyte by cDNA microarray. (B) Gene Ontology analysis of downregulation and (C) Gene Ontology analysis of upregulation. GO enrichment analysis demonstrated that signaling pathways associated with liver function were the most significantly upregulated, and cell cycle-associated signaling pathways were the most significantly downregulated in 3D hepatocyte-like cells, relative to mouse BM-MSCs. GO, gene ontology; BM-MSCs, bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells.

Discussion

A limitation of traditional methods for the induction of differentiation of adherent monolayer hepatocyte-like cells is low differentiation efficiency (26). In the present study, a novel 3D culture system was established to obtain differentiated hepatocyte cells from spheroid cultures and DLSs.

Using a simplified portal vein perfusion procedure, porcine liver was effectively decellularized and examined under a scanning electron microscope. Subsequently, the 3D model was utilized. In our previous study, spheroids were pipetted onto the center of the DLS to allow spontaneous attachment. However, certain spheroids detached from the DLS in the early stages of culture (8,22). In the present study, a negative pressure suction device was utilized to ensure the efficient attachment of spheroids to the DLS.

A simple, efficient tool for real-time monitoring of hepatocyte differentiation from stem cells is useful. As the adenoviral vector is commonly utilized for gene expression studies due to its efficient transduction, an Albp-ZsGreen adenoviral vector was constructed to detect hepatocyte-like cells. Following the second induction period, green fluorescence was detected at an earlier stage in 3D cells compared with 2D cells and the fluorescence intensity in 3D cells was significantly greater in a time-dependent manner (data not shown).

Ammonia is a product of protein metabolism and requires clearance by the liver. A functional urea cycle is an important characteristic of mature hepatocytes. To assess urea production and the detoxification of ammonia via the urea cycle, heavy ammonium chloride was added to the culture medium. The concentration of urea produced by differentiated cells in the 3D group was greater compared with the 2D group. In addition, the results of the present study demonstrated that ~20% of urea was produced by urea cycle activity in 3D cells, which was significantly greater compared with 2D cells.

The liver is the largest internal organ providing essential metabolic, exocrine and endocrine functions. These functions include production of bile, metabolism of dietary compounds, detoxification, regulation of glucose levels via glycogen storage and control of blood homeostasis by secretion of clotting factors and serum proteins, including ALB. In the present study, GO analysis revealed that the majority of upregulated genes were associated with liver function, whereas cell cycle-associated pathways were significantly downregulated.

In conclusion, the results of the present study suggested that a 3D culture system may promote hepatic differentiation of mouse MSCs, to generate high yields of mature hepatocytes. This miniaturized culture system may possess unique advantages over previous methods and may provide a potential strategy for cell transplantation and drug research.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the National Key Clinical Project, the National Natural Scientific Foundations of China (grant no. 81200315) and the Doctoral Program of Colleges and Universities Specialized Research Foundation (grant no. 20120181110090).

References

- 1.Brown RS., Jr Live donors in liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1802–1813. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fox IJ, Daley GQ, Goldman SA, Huard J, Kamp TJ, Trucco M. Use of differentiated pluripotent stem cells in replacement therapy for treating disease. Science. 2014;345:1247391. doi: 10.1126/science.1247391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chistiakov DA. Liver regenerative medicine: Advances and challenges. Cells Tissues Organs. 2012;196:291–312. doi: 10.1159/000335697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forbes SJ, Newsome PN. New horizons for stem cell therapy in liver disease. J Hepatol. 2012;56:496–499. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badylak SF, Doris T, Korkut U. Whole-organ tissue engineering: Decellularization and recellularization of three-dimensional matrix scaffolds. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2011;13:27–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071910-124743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baer PC, Griesche N, Luttm W, Schubert R, Luttm A, Geiger H. Human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells in vitro: Evaluation of an optimal expansion medium preserving stemness. Cytotherapy. 2010;12:96–106. doi: 10.3109/14653240903377045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park E, Patel AN. Changes in the expression pattern of mesenchymal and pluripotent markers in human adipose-derived stem cells. Cell Biol Int. 2010;34:979–984. doi: 10.1042/CBI20100124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y, Wu Q, Wang Y, Li L, Chen F, Shi Y, Bao J, Bu H. Construction of bioengineered hepatic tissue derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells via aggregation culture in porcine decellularized liver scaffolds. Xenotransplantation. 2017;24:e12285. doi: 10.1111/xen.12287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin SJ, Jee SH, Hsiao WC, Yu HS, Tsai TF, Chen JS, Hsu CJ, Young TH. Enhanced cell survival of melanocyte spheroids in serum starvation condition. Biomaterials. 2006;27:1462–1469. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frith JE, Thomson B, Genever PG. Dynamic three-dimensional culture methods enhance mesenchymal stem cell properties and increase therapeutic potential. Tissue Engineering Part C Methods. 2010;16:735–749. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2009.0432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y, Guo G, Li L, Chen F, Bao J, Shi YJ, Bu H. Three-dimensional spheroid culture of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells promotes cell yield and stemness maintenance. Cell Tissue Res. 2015;360:297–307. doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-2055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uygun BE, Soto-Gutierrez A, Yagi H, Izamis ML, Guzzardi MA, Shulman C, Milwid J, Kobayashi N, Tilles A, Berthiaume F, et al. Organ reengineering through development of a transplantable recellularized liver graft using decellularized liver matrix. Nat Med. 2010;16:814–820. doi: 10.1038/nm.2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ott HC, Matthiesen TS, Goh SK, Black LD, Kren SM, Netoff TI, Taylor DA. Perfusion-decellularized matrix: Using nature's platform to engineer a bioartificial heart. Nat Med. 2008;14:213–221. doi: 10.1038/nm1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song JJ, Guyette JP, Gilpin SE, Gabriel G, Vacanti JP, Ott HC. Regeneration and experimental orthotopic transplantation of a bioengineered kidney. Nat Med. 2013;19:646–651. doi: 10.1038/nm.3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ott HC, Clippinger BC, Schuetz C, Pomerantseva I, Ikonomou L, Kotton D, Vacanti JP. Regeneration and orthotopic transplantation of a bioartificial lung. Nat Med. 2010;16:927–933. doi: 10.1038/nm.2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crapo PM, Gilbert TW, Badylak SF. An overview of tissue and whole organ decellularization processes. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3233–3243. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lang R, Stern MM, Smith L, Liu Y, Bharadwaj S, Liu G, Baptista PM, Bergman CR, Soker S, Yoo JJ, et al. Three-dimensional culture of hepatocytes on porcine liver tissue-derived extracellular matrix. Biomaterials. 2011;32:7042–7052. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ji R, Zhang N, You N, Li Q, Liu W, Jiang N, Liu J, Zhang H, Wang D, Tao K, Dou K. The differentiation of MSCs into functional hepatocyte-like cells in a liver biomatrix scaffold and their transplantation into liver-fibrotic mice. Biomaterials. 2012;33:8995–9008. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang WC, Cheng YH, Yen MH, Chang Y, Yang VW, Lee OK. Cryo-chemical decellularization of the whole liver for mesenchymal stem cells-based functional hepatic tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2014;35:3607–3617. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou P, Lessa N, Estrada DC, Severson EB, Lingala S, Zern MA, Nolta JA, Wu J. Decellularized liver matrix as a carrier for the transplantation of human fetal and primary hepatocytes in mice. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:418–427. doi: 10.1002/lt.22270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu Q, Bao J, Zhou YJ, Wang YJ, Du ZG, Shi YJ, Li L, Bu H. Optimizing perfusion-decellularization methods of porcine livers for clinical-scale whole-organ bioengineering. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:785474. doi: 10.1155/2015/785474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bao J, Wu Q, Wang Y, Li Y, Li L, Chen F, Wu X, Xie M, Bu H. Enhanced hepatic differentiation of rat bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in spheroidal aggregate culture on a decellularized liver scaffold. Int J Mol Med. 2016;38:457–465. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2016.2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartz RE, Reyes M, Koodie L, Jiang Y, Blackstad M, Lund T, Lenvik T, Johnson S, Hu WS, Verfaillie CM. Multipotent adult progenitor cells from bone marrow differentiate into functional hepatocyte-like cells. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1291–1302. doi: 10.1172/JCI0215182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang J, Wu Q, Li Y, Wu X, Wang Y, Zhu L, Shi Y, Bu H, Bao J, Xie M. Construction of a general albumin promoter reporter system for real-time monitoring of the differentiation status of functional hepatocytes from stem cells in mouse, rat and human. Biomed Rep. 2017;6:627–632. doi: 10.3892/br.2017.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bao J, Fisher JE, Lillegard JB, Wang W, Amiot B, Yu Y, Dietz AB, Nahmias Y, Nyberg SL. Serum-free medium and mesenchymal stromal cells enhance functionality and stabilize integrity of rat hepatocyte spheroids. Cell Transplant. 2013;22:299–308. doi: 10.3727/096368912X656054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Książek K. A Comprehensive review on mesenchymal stem cell growth and senescence. Rejuvenation Res. 2009;12:105–116. doi: 10.1089/rej.2009.0830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]