Abstract

Aging is the major risk factor for diseases of the cardiovascular system, such as coronary atherosclerotic heart disease, but little is known about the relationship between atherosclerosis (AS) and age-related declines in vascular structure and function. Here, we used histological analyses in combination with molecular biology techniques to show that lipid deposition in endothelial cell was accompanied by aging and growth arrest. Endothelial cell senescence is sufficient to cause AS; however, we found that salidroside reduced intracellular lipid deposition, slowed the progression of endothelial cell senescence and inhibited the expression of the senescence-related molecules and phosphorylated the retinoblastoma (Rb) protein. Further study confirmed that salidroside increased the percent of S phase cells in oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL)-treated endothelial cells. Collectively, vascular endothelial cell function declined with age and AS, and our data suggested that salidroside prevented ox-LDL-treated endothelial cell senescence by promoting cell cycle progression from G0/G1 phase to S phase via Rb phosphorylation. We demonstrated for the first time the complex interactions between AS and endothelial cell senescence, and we believe that salidroside represents a promising therapy for senescence-related AS.

Keywords: salidroside, aging, atherosclerosis, endothelial cell, lipid deposition

Introduction

The effect of aging on atherosclerosis (AS) can be explained by the observation that the prevalence of AS increases progressively with age. Functional and morphological changes in healthy aged vascular tissue lead to decreases in arterial elasticity that affect reservoir function and pulse pressure in older adults and are considered a predictor of several cardiovascular outcomes, such as stroke and myocardial infarction (1). Age-related oxidative damage and vascular inflammation are the main causes of arterial dysfunction. Nitric oxide (NO) is the most important regulator of vascular endothelial function, and its bioavailability enables it to play a prominent role during the initial stages of AS, which are characterized by the combination of endothelial damage and lipid infiltration (2). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) induced activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) promotes AS via the release of several cytokines and adhesion molecules, which collectively contribute to AS progression (3,4). Recently, increasing amounts of evidence have linked vascular endothelial cell senescence to AS development (5,6), but the biological mechanisms underlying this relationship need to be studied further. Migliaccio et al found that genetic p66Shc deletions decrease ROS levels and prolong mouse lifespans by 30% and that p53 and p21 mediated stress responses are impaired in p66shc-/− cells (7). p66Shc is also involved in the pathology of AS and is a key determinant of aging. p66Shc silencing attenuates oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL)-induced ROS production in endothelial cells (8) and reduces plaque formation in ApoE−/− mice subjected to a high-cholesterol diet (9). Here, we showed that ox-LDL-induced varieties in senescence-related protein occurred in conjunction with senescence-related increases in lipid deposition in EA.hy926 endothelial cell, but the biological mechanisms underlying the promotion of cell senescence have not been completely elucidated. Some studies have demonstrated that p16 levels gradually increase in senescent human diploid fibroblasts, reaching levels that are approximately 40-fold higher than those of early passaged cells (10), and that increased cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A, isoform INK4a (p16INK4a) expression leads to retinal ganglion cell senescence in adult human retinas (11). It is known that p16 is the major cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor and that p16 upregulation is a key event in growth arrest-related cell senescence. It is now considered that p21 was involved in regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, senescence, and apoptosis (12). And recent report confirmed that p21-mediated cellular senescence was p53-independent (13). In ox-LDL-induced senescent EA.hy926 cells, the levels of p53, p21 and p16 mRNA and cellular protein expression were increased dramatically, the phosphorylated retinoblastoma (Rb) level was decreased, and the cell cycle was arrested in G0/G1 phase. We confirmed that decreases in phosphorylated Rb protein levels may underlie the development of EA.hy926 cell senescence.

Salidroside, one of the active ingredients of Rhodiolacrenulata, can be used as an effective anti-diabetes agent (14), can protect against Aβ-induced neurotoxicity in transgenic Drosophila Alzheimer's disease (AD) models (15), and can also alleviate oxidative stress (16) and inflammation (17) in different cell and animal models; however, there are little data suggesting that salidroside protects against age-related AS. Xing et al showed that salidroside plays a critical role in promoting NO production and activating AMPK signaling pathway to improve endothelial function in AS (18) and Some study indicated that salidroside could attenuate H2O2 induced cell death by inhibiting caspase-3, 9 and cleavage of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) activation (19). Our previous study found that aging cells exist in atherosclerotic plaque of high-fat diet ApoE−/− mice, and salidroside could decrease the aging cells. In the present study, we investigated the protective effects of salidroside against ox-LDL-induced EA.hy926 cell senescence and explored the mechanisms underlying ox-LDL induced endothelial cell senescence. We showed that salidroside significantly protected cultured EA.hy926 cells against ox-LDL-induced cytotoxicity. Furthermore, we provided evidence that these effects were induced by changes in the expression of senescence-related molecular targets (p66, p53 and p21) in the phosphorylated Rb protein signaling pathway.

Materials and methods

EA.hy926 cells culture and proliferation assay

Human umbilical vein EA.hy926 cells (Cell bank, Shanghai Institute for Biological Science, Shanghai, China) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Invitrogen, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen, CA, USA) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. Cells were passaged according to the number of cells required for different experiments. The second day after passage, the cells were incubated with 10, 100, 250 and 500 µg/ml ox-LDL (Yuanye Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) and/or with 500 µM salidroside (purity, >98%; Yuanye Biotechnology; 50 µM pravastatin was used as a positive control) for 48 h to establish lipid oxidation and AS therapy models. Then, the cells were incubated with 20 µl of CCK-8 (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) for 2 h, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cell proliferation was analyzed using a microplatereader, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany).

Oil Red O and senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining

Oil Red O staining was carried out to assess cellular lipid accumulation. Briefly, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 30 min and then stained with 0.05% Oil Red O solution in 60% isopropanol for 30 min at room temperature. The cells were subsequently decolorized with 75% alcohol/60% isopropanol for 2 min before being photographed and analyzed using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics Inc., Rockville, MD, USA).

Senescent EA.hy926 cells express a β-gal, which was detected using a Beta Galactosidase (β-gal) Activity Assay kit (BioVison, Milpitas, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions, based on the formation of a local blue precipitate upon enzyme-mediated cleavage. Briefly, the cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature and washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Freshly prepared aged x-gal solution was used to stain senescent cells for approximately 18–24 h at 37°C. Then, the cells were observed via lightmicroscopy, and the percentages of β-gal-positive cells were calculated.

RNA isolation and real-time PCR assay

Total RNA from EA.hy926 cells was prepared using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription was performed using a PrimeScript™ II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Takara, Shiga Prefecture, Japan), according to the manufacturer's instructions, and cDNA was used as a template for PCR amplification of the target mRNA fragments. A SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ (TliRNaseH Plus; Takara, Shiga Prefecture, Japan) system was used for all real-time PCR reactions. The comparative threshold cycle (ΔCq) method was used to quantify target mRNA levels at different time points. Target mRNA levels were normalized to an endogenous reference 18S rRNA and a control. The following primer pairs were used: p66 sense, 5′-GGTTCATGTTAACCAGGCCA-3′ and anti-sense, 5′-TGAGACTGCCAGACACCAAG-3′; p53 sense, 5′-GCTTTCCACGACGGTGAC-3′ and anti-sense, 5′-GCTCGACGCTAGGATCTGAC-3′); p21 sense, 5′-AGTCAGTTCCTTGTGGAGCC-3′ and anti-sense, 5′-CATGGGTTCTGACGGACAT-3′; p16 sense, 5′-CCCAACGCACCGAATAGTTA-3′ and anti-sense, 5′-GGTCGGGTGAGAGTGGC-3′); and 18S rRNA sense, 5′-TAGTAGCGACGGGCGGTGTG-3′ and anti-sense, 5′-CAGCCACCCGAGTTGAGCA-3′).

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (20). Primary polyclonal anti-p66, anti-p53, anti-p27, anti-p21, anti-p16, anti-CDK4, anti-cyclin D1, anti-p-Akt, anti-Akt, anti-p-Erk, anti-Erk, anti-p-Rb, anti-Rb and anti-β-actin antibodies were all purchased from Abcam (Abcam, Massachusetts, USA). After the cells were incubated with a secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Ig)G antibody (1:10,000; SABC) for 1 h at 37°C, signals were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) and quantified via densitometric analysis using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics).

Cell cycle analysis

Changes in EA.hy926 cell cycle progression induced by ox-LDL treatment were investigated by flow cytometry. Briefly, cells (1×105) were harvested and fixed with cold 75% ethanol for 24 h at −20°C. Then, the cells were rinsed with PBS and incubated with 150 µl of RNase A (100 µg/µl; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 0.05% Triton X-100 for 30 min at 37°C before being resuspended in 2 ml of PBS and 100 µl of propidium iodide (PI; 2.5 mg/ml) and incubated for 30 min at 4°C. Cell cycle distribution (2×104 cells) was determined using a CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, USA), and analysis was performed using MultiCycle software (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 18.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). The results are expressed as the mean ± SD, as indicated in the figure. legends. One-way ANOVA and Tukey HSD post hoc t-tests were used to determine the level of statistical significance. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Salidroside attenuates lipid accumulation and senescence in endothelial cells

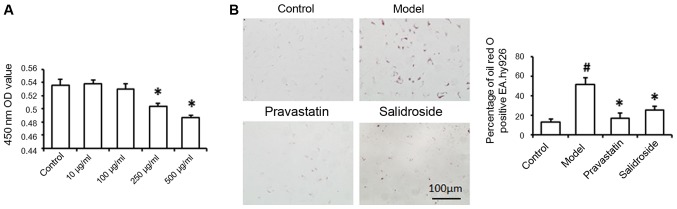

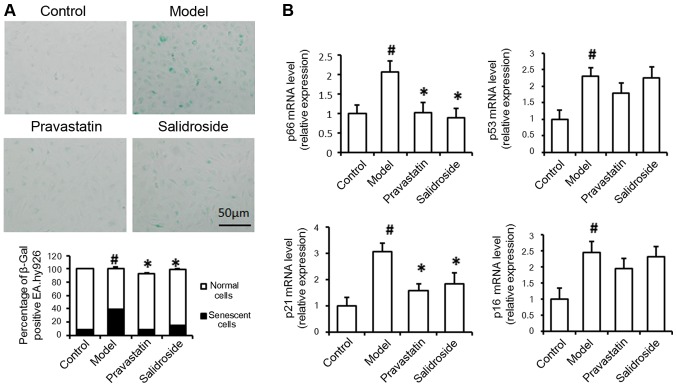

In order to prepare AS cell model, ox-LDL at different concentration was incubated with EA.hy926 cells, finally, 100 µg/ml ox-LDL was used to induce lipid damage in EA.hy926 cells (Fig. 1A). At the same time, EA.hy926 cells were treated with salidroside for 2 days. To ascertain the effects of salidroside on lipid deposition and cell senescence, Oil Red O staining and SA-β-gal staining were performed, respectively. As shown in Fig. 1B, the relative percentage of Oil Red O-positive cells was significantly lower in the salidroside group than in the ox-LDL group, indicating that intracellular lipid accumulation was successfully induced in EA.hy926 cells by ox-LDL and that salidroside treatment prevents ox-LDL-induced lipid accumulation in the cytoplasm. This finding suggests that salidroside administration attenuates lipid accumulation in endothelial cells. Histological analysis of SA-β-gal-stained cells revealed significant reductions in the numbers of positively stained cells in the salidroside-treated group compared with the ox-LDL model group (Fig. 2A). Therefore, we further examined the effect of salidroside on p66, p53, p21 and p16 mRNA expression, results indicated that the levels of p66 and p21 mRNA expression were significantly decreased in ox-LDL plus salidroside-treated cells compared with ox-LDL-treated cells (Fig. 2B). Therefore, we hypothesized that ox-LDL-induced damage may lead to cell aging in cultured EA.hy926 cells, and salidroside improved cell senescence in ox-LDL induced cell AS model.

Figure 1.

Effects of salidroside on ox-LDL-induced EA.hy926 cell damage. (A) Cells were treated with 10, 100, 250 and 500 µg/ml ox-LDL and CCK-8 assay detected the cell damage. (B) Cells were treated with 100 µg/ml ox-LDL alone (model) or ox-LDL, 500 µM salidroside (salidroside) for 48 h, normal cells without any treatment (control) and pravastatin (positive control). Oil Red O staining showing lipid deposition in the cell cytoplasm, and according to the staining results, we calculated the percentage of Oil Red O positive cells. Pravastatin was used as a positive control. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation from 3 independent experiments. #P<0.05 vs. control and *P<0.05 vs. model. Scale bar, 100 µm. ox-LDL, oxidized low-density lipoprotein.

Figure 2.

Salidroside treatment represses cell aging and senescence-related molecule mRNA expression. (A) EA.hy926 cells treated with 100 µg/ml ox-LDL (model) were subjected to SA-β-gal analysis. (B) Quantitative polymerase chain reaction was used to determine the relative levels of p66, p53, p21 and p16 mRNA expression in normal cells without any treatment (control), cells treated with 100 µg/ml ox-LDL alone (model), cells were treated with ox-LDL and 500 µM salidroside (salidroside group) and pravastatin (positive control). Data represent the mean ± standard deviation from 3 independent experiments. #P<0.05 vs. control and *P<0.05 vs. model. Scale bar, 50 µm. ox-LDL, oxidized low-density lipoprotein; SA-β-gal, senescence-associated β-galactosidase; p53, cellular tumor antigen 53; p21, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1; p16, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A.

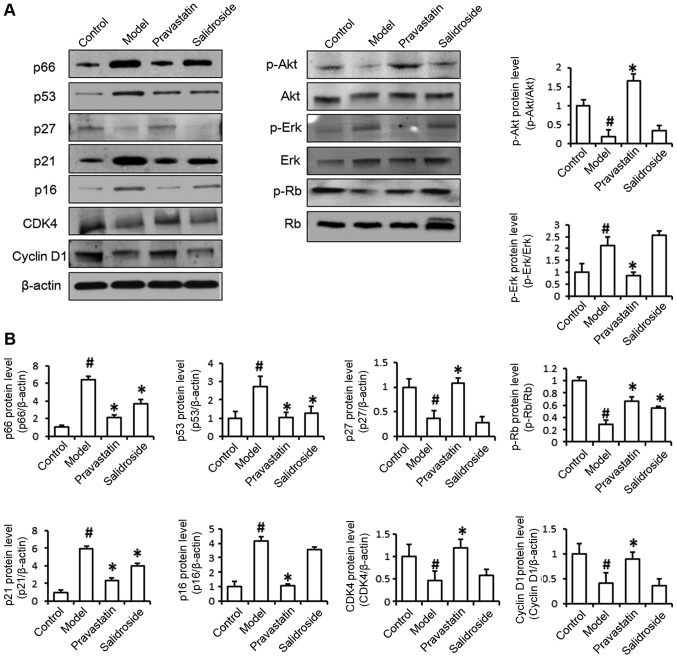

Salidroside decreases p66, p53 and p21 expression in ox-LDL-treated endothelial cells

We examined the effect of salidroside on senescence-related protein expression. As shown in Fig. 3, the levels of p66, p53 and p21 protein expression were significantly decreased in ox-LDL and salidroside-treated cells compared with ox-LDL-treated cells, the levels of p27, p16, CDK4, Cyclin-D1, p-Akt and p-Erk have no differences between two groups. Western blot analysis indicated that the increases in p66, p53 and p21 expression induced by ox-LDL were all significantly reversed by salidroside. The above results demonstrate that ox-LDL treatment induces EA.hy926 cell senescence and that salidroside prevents cell senescence by decreasing the expression of aging-related proteins. In order to further detect the regulation mechanisms of senescence-related protein in ox-LDL induced EA.hy926 damage, and according to previous study that the senescence-related proteins p21 participate in cell cycle regulation, therefore, we examined the effects of salidroside on cell cycle protein Rb phosphorylation to determine whether Rb protein is the target of salidroside. As shown in Fig. 3, phosphorylated Rb protein levels were significantly increased by salidroside treatment compared with ox-LDL treatment.

Figure 3.

Salidroside treatment represses senescence-related protein expression. (A) The levels of p66, p53, p27, p21, p16, CDK-4, Cyclin D1, p-Akt, Akt, p-Erk, Erk, p-Rb and Rb protein expression were detected by western blotting. It is showed that protein levels of p66, p53 and p21 were decreased in ox-LDL (model) and salidroside-treated cells compared with ox-LDL-treated cells, protein levels of p27, p16, CDK4, Cyclin-D1, p-Akt and p-Erk have no differences between two groups. (B) The histogram of the analysis of the protein bands. Pravastatin was used as a positive control. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation from 3 independent experiments. #P<0.05 vs. control and *P<0.05 vs. model. Ox-LDL, oxidized low-density lipoprotein; p53, cellular tumor antigen 53; p21, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1; p16, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A; CDK-4, cyclin-dependent kinase-4; Akt, protein kinase B; p, phosphorylated; Erk, extracellular signal-related kinase; Rb, retinoblastoma.

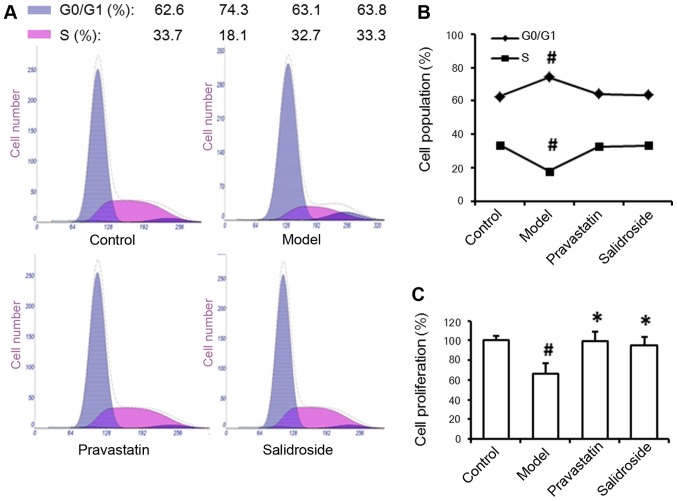

Salidroside prevents cell cycle arrest via Rb phosphorylation in senescent endothelial cells

According to the result that salidroside could phosphorylate Rb protein, we examined the effects of salidroside on cell cycle progression in ox-LDL-treated EA.hy926 cells to more fully elucidate the mechanisms by which inhibiting aging-related protein expression prevents endothelial cell senescence. In the setting of ox-LDL treatment, the percentage of EA.hy926 cells in G0/G1 phase was significantly enhanced, whereas the percentage of cells in S phase was markedly reduced. However, the cell cycle profile of the salidroside-treated group was characterized by an increase in the percentage of cells in S phase and a reduced fraction of cells in G0/G1 phase (Fig. 4A and B). Our cell proliferation assay results confirmed that salidroside also promoted EA.hy926 cell proliferation (Fig. 4C). These results suggested that salidroside-induced senescence-related protein downregulation was involved in EA.hy926 cell cycle progression. Overall, these results indicated that salidroside regulated the cell cycle to slow cell senescence. Taken together, our findings indicate that salidroside-mediated p66, p53 and p21 regulation and Rb phosphorylation influence ox-LDL-induced endothelial cell senescence.

Figure 4.

Salidroside influences the percent of cells in G1 and S by regulating Rb phosphorylation. (A) Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of EA.hy926 cell cycle progression. (B) Quantitative analysis of cell cycle activity in cells subjected to ox-LDL treatment alone (model) or ox-LDL and salidroside treatment for 48 h. (C) Analysis of EA.hy926 cell proliferation under different culture conditions. Pravastatin was used as a positive control. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation of 3 independent experiments. #P<0.05 vs. control and *P<0.05 vs. model. ox-LDL, oxidized low-density lipoprotein; Rb, retinoblastoma.

Discussion

Endothelial senescence is characterized by reduced endothelial function accompanied by vascular functional impairment and AS plaque formation. Approaches designed to retard the aging process are expected to have therapeutic value with respect to AS prevention and treatment. Salidroside is a major active ingredient from the medicinal plant Rhodiola rosea L. and is commonly used as an antioxidant (21), anti-inflammatory (22) and an anti-lipid agent (23). Although salidroside has been shown to be useful in treating various types of diseases, its effects on vascular endothelial cell senescence-related AS development are still unclear. In the present study, we demonstrated that salidroside was capable of protecting vascular endothelial cells from lipid deposition and senescence caused by exogenous ox-LDL-induced damage. Then, we explored the possible molecular mechanisms underlying the anti-aging effects of salidroside on senescence-related molecule expression and found that salidroside promoted cell cycle progression from G0/G1 phase to S phase via Rb phosphorylation.

Endothelial cell senescence in atherosclerotic lesions is related to the expression of various aging-related genes, which contribute to decreases in vasodilation and increases in lipid infiltration. Our results demonstrate that salidroside decreases cholesterol deposition in EA.hy926 cells and facilitates migration capacity recovery and indicate that salidroside very likely prevents cell senescence. Impaired endothelial function is the hallmark of endothelial senescence, which is mediated primarily by the aging-related proteins, which are produced by aging cells, play important roles in endothelial senescence and are involved in multiple processes that cause endothelial dysfunction, including oxidative stress and energy metabolism (24,25).

In the present study, salidroside treatment decreased the protein levels of p66, p53 and p21 protein expression in ox-LDL-treated EA.hy926 cells in an in vitro AS model, but the mRNA levels of p53 did not show differences between two groups, it's mean that the posttranslational modifications might decide the p53 protein level. In addition, changes in the numbers of SA-β-gal-positive EA.hy926 cells coincided with changes in the levels of the abovementioned aging-related proteins. These results are in accordance with those of previous studies showing the inhibitory effects of salidroside on adipogenesis (26) and cell senescence (27). The molecular mechanisms underlying cellular senescence are generally very sophisticated. According to previous reports, most researchers believe that the p53-p21 and p16-pRb pathways are the main regulators of senescence (28). These senescence-related pathways can be activated by telomere shortening, DNA damage or oxidative stress (29). The signaling pathways activated by these stresses facilitate increases in p53 and Rb protein expression, the combined levels of which determine whether cells enter senescence (30). However, as various endogenous and exogenous stimuli cause specific types of cell damage, the senescence pathway that is activated may vary depending on the cell-type. In our study, both the p53-p21 pathway and the p16-pRb pathway were activated in ox-LDL-treated EA.hy926 cells. We subsequently assessed cell cycle progression via PI staining and confirmed that ox-LDL-treated cells arrested in G0/G1 phase. These results indicate that Rb phosphorylation inhibits cell senescence induced by the aging-related p53-p21 and p16-pRb pathways. The mechanisms underlying pRb pathway-mediated cell growth are complex (31). In senescent cells, pRb dephosphorylation blocks mitogenic signaling and leaves the cells in G1 phase (32); however, the results of studies regarding Rb function are controversial. Additional studies regarding the molecular mechanisms underlying cell senescence are needed.

Previous studies have shown that salidroside has anti-fatigue, anti-aging, immune regulation, free radical scavenging and other pharmacological effects. Inour study, we found that salidroside ameliorates ox-LDL-induced lipid deposition, growth arrest and cell senescence in EA.hy926 cells. Its possible mechanism is that salidroside inhibits the protein expression of p53, p21 and p16, promotes phosphorylation of Rb protein, promotes cell entry into S phase, prevent pre-aging of cells. Non-aging cells can prevent excessive intracellular lipid deposition by accelerating cholesterol transport. Therefore, we concluded that salidroside prevented the development of AS by inhibiting cell senescence.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Wengong Wang (Peking University Health Science Center) for his helpful comments on the manuscript. The present study was supported by grants from Natural Science Foundation of China (program no. 81373706, 81503626) and from the Shanghai Health Bureau Youth Fund (program no. 201540254).

References

- 1.Hashimoto J, Ito S. Aortic stiffness determines diastolic blood flow reversal in the descending thoracic aorta: Potential implication for retrograde embolic stroke in hypertension. Hypertension. 2013;62:542–549. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li H, Horke S, Förstermann U. Vascular oxidative stress, nitric oxide and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2014;237:208–219. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tousoulis D, Oikonomou E, Economou EK, Crea F, Kaski JC. Inflammatory cytokines in atherosclerosis: Current therapeutic approaches. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:1723–1732. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah P, Bajaj S, Virk H, Bikkina M, Shamoon F. Rapid progression of coronary atherosclerosis: A review. Thrombosis. 2015;2015:634983. doi: 10.1155/2015/634983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Camici GG, Savarese G, Akhmedov A, Luscher TF. Molecular mechanism of endothelial and vascular aging: Implications for cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:3392–3403. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi Y, Camici GG, Lüscher TF. Cardiovascular determinants of life span. Pflugers Arch. 2010;459:315–324. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0727-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Migliaccio E, Giorgio M, Mele S, Pelicci G, Reboldi P, Pandolfi PP, Lanfrancone L, Pelicci PG. The p66shc adaptor protein controls oxidative stress response and life span in mammals. Nature. 1999;402:309–313. doi: 10.1038/46311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi Y, Cosentino F, Camici GG, Akhmedov A, Vanhoutte PM, Tanner FC, Lüscher TF. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein activates p66Shc via lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1, protein kinase C-beta and c-Jun N-terminal kinase kinase in human endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2090–2097. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.229260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin-Padura I, de Nigris F, Migliaccio E, Mansueto G, Minardi S, Rienzo M, Lerman LO, Stendardo M, Giorgio M, De Rosa G, et al. p66Shc deletion confers vascular protection in advanced atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Endothelium. 2008;15:276–287. doi: 10.1080/10623320802487791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou R, Han L, Li G, Tong T. Senescence delay and repression of p16INK4a by Lsh via recruitment of histone deacetylases in human diploid fibroblasts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:5183–5196. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skowronska-Krawczyk D, Zhao L, Zhu J, Weinreb RN, Cao G, Luo J, Flagg K, Patel S, Wen C, Krupa M, et al. P16INK4a upregulation mediated by SIX6 defines retinal ganglion cell pathogenesis in glaucoma. Mol Cell. 2015;59:931–940. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romanov VS, Pospelov VA, Pospelova TV. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 (Waf1): Contemporary view on its role in senescence and oncogenesis. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2012;77:575–584. doi: 10.1134/S000629791206003X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shih CT, Chang YF, Chen YT, Ma CP, Chen HW, Yang CC, Lu JC, Tsai YS, Chen HC, Tan BC. The PPARgamma-SETD8 axis constitutes an epigenetic, p53-independent checkpoint on p21-mediated cellular senescence. Aging Cell. 2017;16:797–813. doi: 10.1111/acel.12607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang M, Luo L, Yao L, Wang C, Jiang K, Liu X, Xu M, Shen N, Guo S, Sun C, Yang Y. Salidroside improves glucose homeostasis in obese mice by repressing inflammation in white adipose tissues and improving leptin sensitivity in hypothalamus. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25399. doi: 10.1038/srep25399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang B, Wang Y, Li H, Xiong R, Zhao Z, Chu X, Li Q, Sun S, Chen S. Neuroprotective effects of salidroside through PI3K/Akt pathway activation in Alzheimer's disease models. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2016;10:1335–1343. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S99958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang ZR, Wang HF, Zuo TC, Guan LL, Dai N. Salidroside alleviates oxidative stress in the liver with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in rats. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016;17:16. doi: 10.1186/s40360-016-0059-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qi Z, Qi S, Ling L, Lv J, Feng Z. Salidroside attenuates inflammatory response via suppressing JAK2-STAT3 pathway activation and preventing STAT3 transfer into nucleus. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016;35:265–271. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xing SS, Yang XY, Zheng T, Li WJ, Wu D, Chi JY, Bian F, Bai XL, Wu GJ, Zhang YZ, et al. Salidroside improves endothelial function and alleviates atherosclerosis by activating a mitochondria-related AMPK/PI3 K/Akt/eNOS pathway. Vascul Pharmacol. 2015;72:141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao X, Jin L, Shen N, Xu B, Zhang W, Zhu H, Luo Z. Salidroside inhibits endogenous hydrogen peroxide induced cytotoxicity of endothelial cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2013;36:1773–1778. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b13-00406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dou F, Huang L, Yu P, Zhu H, Wang X, Zou J, Lu P, Xu XM. Temporospatial expression and cellular localization of oligodendrocyte myelin glycoprotein (OMgp) after traumatic spinal cord injury in adult rats. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26:2299–2311. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.0954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calcabrini C, De Bellis R, Mancini U, Cucchiarini L, Potenza L, De Sanctis R, Patrone V, Scesa C, Dachà M. Rhodiola rosea ability to enrich cellular antioxidant defences of cultured human keratinocytes. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302:191–200. doi: 10.1007/s00403-009-0985-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pooja, Bawa AS, Khanum F. Anti-inflammatory activity of Rhodiola rosea- ‘a second-generation adaptogen’. Phytother Res. 2009;23:1099–1102. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J, Rong X, Li W, Yang Y, Yamahara J, Li Y. Rhodiola crenulata root ameliorates derangements of glucose and lipid metabolism in a rat model of the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;142:782–788. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bianchi G, Di Giulio C, Rapino C, Rapino M, Antonucci A, Cataldi A. p53 and p66 proteins compete for hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha stabilization in young and old rat hearts exposed to intermittent hypoxia. Gerontology. 2006;52:17–23. doi: 10.1159/000089821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hooten Noren N, Martin-Montalvo A, Dluzen DF, Zhang Y, Bernier M, Zonderman AB, Becker KG, Gorospe M, de Cabo R, Evans MK. Metformin-mediated increase in DICER1 regulates microRNA expression and cellular senescence. Aging Cell. 2016;15:572–581. doi: 10.1111/acel.12469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pomari E, Stefanon B, Colitti M. Effects of two different Rhodiola rosea extracts on primary human visceral adipocytes. Molecules. 2015;20:8409–8428. doi: 10.3390/molecules20058409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mao GX, Wang Y, Qiu Q, Deng HB, Yuan LG, Li RG, Song DQ, Li YY, Li DD, Wang Z. Salidroside protects human fibroblast cells from premature senescence induced by H(2)O(2) partly through modulating oxidative status. Mech Ageing Dev. 2010;131:723–731. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beauséjour CM, Krtolica A, Galimi F, Narita M, Lowe SW, Yaswen P, Campisi J. Reversal of human cellular senescence: Roles of the p53 and p16 pathways. EMBO J. 2003;22:4212–4222. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin N, Raguz S, Dharmalingam G, Gil J. Co-regulation of senescence-associated genes by oncogenic homeobox proteins and polycomb repressive complexes. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:2194–2199. doi: 10.4161/cc.25331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ben-Porath I, Weinberg RA. The signals and pathways activating cellular senescence. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:961–976. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nevins JR. The Rb/E2F pathway and cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:699–703. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.7.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. RAS oncogenes: The first 30 years. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:459–465. doi: 10.1038/nrc1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]