Abstract

The impact of traumatic brain injury during the perinatal period, which coincides with glial cell (astrocyte and oligodendrocyte) maturation was assessed to determine whether a second insult, e.g., increased inflammation due to remote bacterial exposure, exacerbates the initial injury’s effects, possibly eliciting longer-term brain damage. Thus, a murine multifactorial injury model incorporating both mechanisms consisting of perinatal penetrating traumatic brain injury, with or without intraperitoneal injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), an analog of remote pathogen exposure has been developed. Four days after injury, gene expression changes for different cell markers were assessed using mRNA in situ hybridization (ISH) and qPCR. Astrocytic marker mRNA levels increased in the stab-alone and stab-plus-LPS treated animals indicating reactive gliosis. Activated microglial/macrophage marker levels, increased in the ipsilateral sides of stab and stab-plus LPS animals by P10, but the differences resolved by P15. Ectopic expression of glial precursor and neural stem cell markers within the cortical injury site was observed by ISH, suggesting that existing precursors and neural stem cells migrate into the injured areas to replace the cells lost in the injury process. Furthermore, single exposure to LPS concomitant with acute stab injury affected the oligodendrocyte population in both the injured and contralateral uninjured side, indicating that after compromise of the blood-brain barrier integrity, oligodendrocytes become even more susceptible to inflammatory injury. This multifactorial approach should lead to a better understanding of the pathogenic sequelae observed as a consequence of perinatal brain insult/injury, caused by combinations of trauma, intrauterine infection, hypoxia and/or ischemia in humans.

Keywords: Perinatal brain injury, astrocyte precursors, oligodendrocytes precursors, neural stem cells, inflammation, lipopolysaccharide

1. Introduction

Individuals suffering brain injuries during the last trimester of gestation and the early postnatal period often develop conditions such as periventricular leukomalacia (PVL) and white matter damage, which in many cases lead to cognitive deficits and/or cerebral palsy (CP) later in childhood (Sewell et al., 2014; Titomanlio et al., 2015). In humans, these perinatal outcomes have been associated with prematurity, low birth weight, maternal systemic infections and/or placental deficiency, neonatal encephalopathy, ischemic stroke, and traumatic injury (Bloch, 2005; Volpe, 2009b), suggesting that the brain is particularly susceptible to injury during this critical phase. A combination of more than one insult may elicit an even more detrimental brain response (Girard et al., 2009; Girard et al., 2012). Several possibilities have been suggested to explain why this period is particularly vulnerable for injury (McClure et al., 2008; Semple et al., 2013). The gliogenesis process is still incomplete; astrocyte precursor migration and maturation has just begun and most oligodendrocyte maturation and myelination occurs postnatally (Back et al., 2001; Clancy et al., 2001; Clancy et al., 2007; Workman et al., 2013). In addition, the blood-brain barrier and brain immune systems are underdeveloped (Melville and Moss, 2013; Moretti et al., 2015). Research efforts examining perinatal brain injury in animal models to assess cellular and molecular mechanisms of injury with the objective of devising therapies that lead to brain repair and regeneration are expanding (Titomanlio et al., 2015; Yager, 2015). Animal models focusing on perinatal asphyxia, hypoxia-ischemia, placental insufficiency, intracerebral hemorrhage, and gestational inflammation have been reported in several species (ferret, rabbit, rat, sheep, pig, primate) (McAdams et al., 2017; Yager, 2015). Although 50% of CP cases occur in normal weight babies and 10% are related to early postnatal infection, accidental brain injury, and/or drowning (Sewell et al., 2014; Titomanlio et al., 2015), no neonatal traumatic injury model has been developed reflecting these etiologies.

From the clinical perspective, traumatic brain injury (TBI) elicits more severe responses during perinatal periods than in adults (Adelson and Kochanek, 1998; Levin et al., 1982). Concussive head trauma in infant rats has been shown to cause extensive neuronal cell death at the trauma site followed by degeneration of other distant neurons (Bayly et al., 2006; Bittigau et al., 1999; Ikonomidou et al., 1996; Pohl et al., 1999). Furthermore, as brain development progresses, there is decreased susceptibility to trauma-induced apoptosis, possibly related to downregulation of the caspase-3 pathway (Yakovlev et al., 2001) and to changes in glutamate homeostasis (Lea and Faden, 2001). In humans and in other animal models, oligodendrocyte loss and astrogliosis after perinatal brain injury have been reported (Marin-Padilla, 1997; Marin-Padilla, 1999; Robinson et al., 2005), but significant questions, such as whether glial precursors are recruited after injury to become mature and/or hypertrophic astrocytes, how oligodendrocytes and their precursors respond to astroglial activation and how proliferation is regulated after injury, remain unanswered. Furthermore, analyses of the responses of astrocytes and their precursors after perinatal stab-wound brain injury are lacking even though these cells may be expected to be key players in controlling glutamate metabolism after injury and in reestablishing the damaged blood-brain barrier. Previously, we established that a stab injury in the developing chick embryo brain leads to many of the phenotypes associated with PVL and that an early response to such injury involves accelerated astrocyte maturation without proliferation, as well as an acute loss of neurons and oligodendrocyte precursors (Domowicz et al., 2011). Unfortunately, avian models lack markers with which to adequately assess the inflammation response and blood-brain-barrier integrity. Thus, we have developed a multifactorial murine model of traumatic stab-wound injury in P6 mouse brain cortex, with and without accompanying induced inflammation. Since inflammation is likely a major risk factor in many forms of perinatal brain damage (maternal systemic infections and bacterial infections in preterm newborns) (Fleiss et al., 2015; Hagberg et al., 2015), we use intraperitoneal LPS injections at the time of brain injury as a model of remote bacterial infection, allowing us to assess near-term effects on the brain and, eventually, to follow long-term consequences for behavioral development.

Traditional models of developmental brain injury have used rodents from postnatal day (P) 7-10 as equivalent to a term human infant, based on measurement of postmortem brains (Dobbing and Sands, 1979). More recently, a series of studies have provided a basis to identify equivalent maturational states across 18 mammalian species (see http://www.translatingtime.net/), encompassing different brain areas and developmental processes (Clancy et al., 2001; Clancy et al., 2007; Workman et al., 2013). In particular, examination of oligodendrocyte maturation in rats and mice suggested white matter development and axonal outgrowth in the rodent CNS at postnatal day 7 is analogous to that seen during 32-36 weeks of gestation in human fetuses (Back et al., 2001), which is the most vulnerable period for brain injury leading to morbidity and mortality in term and pre-term neonates (Lawn et al., 2005). Thus, in order to evaluate the molecular and biochemical changes concurrent with gliogenesis and oligodendrocyte maturation as a consequence of traumatic brain injury in mice, the postnatal window of days 6-10 was chosen for experimentation.

The data obtained with this novel model system indicate that stab injury to the neonatal mouse brain leads to loss of neurons and oligodendrocytes as well as astrocytic precursor activation; while inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) at the time of injury predominantly affects the oligodendrocyte population.

2. Results

2.1 LPS administration induces transient weight loss in neonates

LPS administration, which mimics septicemia in premature human infants (Mallard and Wang, 2012), has previously been shown to induce sickness behavior and weight loss in adult mice (Lawson et al., 2013; Walker et al., 2013), as well as a pro-inflammatory reaction and weight loss in neonatal rodent CNS (Cardoso et al., 2015). Thus, it was necessary to evaluate the contribution of LPS-only treatment in establishing the TBI model. One day (P7) after single LPS injections administrated to either mock-treated stab-injury-control P6 mice or to stab-wound-treated P6 (TBI) mice, delayed neonate growth as measured by weight gain, was observed. This delay continued over the subsequent 3 days, then weight gain started to recover, catching up by day 10 (Fig. 1, inset); non-significant differences in weight loss were observed in LPS treated animals with or without stab wound injury or as late as P15 or P21 (Fig. 1). It should be noted that our use of a single LPS injection was in contrast to previous studies in which multiple-injection regimens administered over several days were observed to cause acute body and brain weight loss, which however were also reversed when LPS administration was terminated (Cardoso et al., 2015). However, multiple injections of LPS in neonates significantly increased mortality, thus all of our experiments were performed with single LPS injections.

Fig. 1. Relative body weight change after injury.

Relative body weight change was calculated as a function of the average body weight at postnatal day 6 (experiment day) for each litter. Mice were mock treated (C), injured in the brain cortex with an 18-gauge needle (SW), treated with LPS (2 μg/g (i.p.)), or subjected to both treatments in succession (SW+LPS). LPS treatment slowed mouse weight gain for three days after the injury. Each point represents an average for 8-16 animals per treatment group. Error bars represent standard deviations for the group data. One-way ANOVA analysis followed by a Tukey’s test was performed between the averages for the four groups at each age to assess significance relative to the control group. *p<0.05

2.2 CNS cell marker expression after stab-wound injury

Developmental programs of the various brain cell types are incomplete at these neonatal stages, thus the impact of injury on cell dynamics was assessed. Neonatal control mice, or mice treated with a single injection of LPS, do not exhibit significant changes in expression of glial (Gfap) or neuronal (Tubb3) marker mRNAs after 4 days (P10). In contrast, stab-wound injury increased astrocyte hypertrophy (as measured by Gfap mRNA levels) along the ventricle in mild cases and also in the cortex and beyond in more severe cases (on the ipsilateral side only) (Fig. 2), and neuronal loss (reduced Tubb3 mRNA levels) primarily around the injury tracks (see Fig. 3). Expression and localization of Gfap mRNA was also increased by concurrent LPS administration and stab-wound injury, predominantly on the ipsilateral side with frequent enlargement of the ipsilateral ventricle. The initial criterion for whether the stab-injury model mimics white matter injuries in humans would be the observation of loss of mature oligodendrocytes. Close-up images (Fig. 3) of the injury region from a representative animal show that although the mature oligodendrocyte marker Plp1 is present on the ipsilateral side, the levels of Plp1 mRNA are lower compared to those of the untreated contralateral side. The extent of the oligodendrocyte lost is also depicted in Fig. 2. Mbp, a marker of mature oligodendrocytes, exhibits a similar pattern, i.e., lower expression of Mbp mRNA on the ipsilateral side compared to the contralateral side (Fig. 3). This corresponds with the expansion of Gfap expression beyond the white matter area on the ipsilateral side compared to the uninjured contralateral side. Also, loss of Tubb3 is evidenced by thinning of the cortex and disruption of the neuronal formation pattern in both the cortex and the hippocampus, on the ipsilateral side only.

Fig. 2. Establishment of the neonatal white matter injury model.

P6 neonates from a single litter were mock treated (C), injected with LPS (2μg/g. i.p.) (LPS), stab-wound-injured (SW) and stab-wound-plus-LPS treated (SW+LPS). P10 brains were collected and processed for in situ hybridization to assess the expression levels of astrocyte (Gfap), neuronal (Tubb3), and oligodendrocyte (Plp1) markers. Control and LPS-alone treatment group brains had no changes in Gfap and Tubb3 mRNA levels. Both SW and SW+LPS groups had increased Gfap mRNA levels and decreased Tubb3 mRNA levels on the ipsilateral (injury) side compared to the contralateral side. Arrows indicate injury sites. Images are representative of 3 independent brains. Scale bar: 2000μm

Fig. 3. Effect of stab injury on the expression patterns of Gfap, Tubb3, and the oligodendrocyte markers Plp1 and Mbp.

Close-up images of stab wound injury sites at P10 show increased Gfap expression in the ipsilateral side throughout parts of the cortex that is not seen on the contralateral side. Disruption of neuronal patterning (Tubb3 expression) is seen in the ipsilateral but not on the contralateral side. The mature oligodendrocyte markers Plp1 and Mbp are less densely expressed on the ipsilateral side, particularly around the injury area, compared to the contralateral side at four days after stab injury (P10). Images are representative of 3 independent brains. Scale bar: 50μm

2.3 Response of precursor/stem cells to stab-wound injury

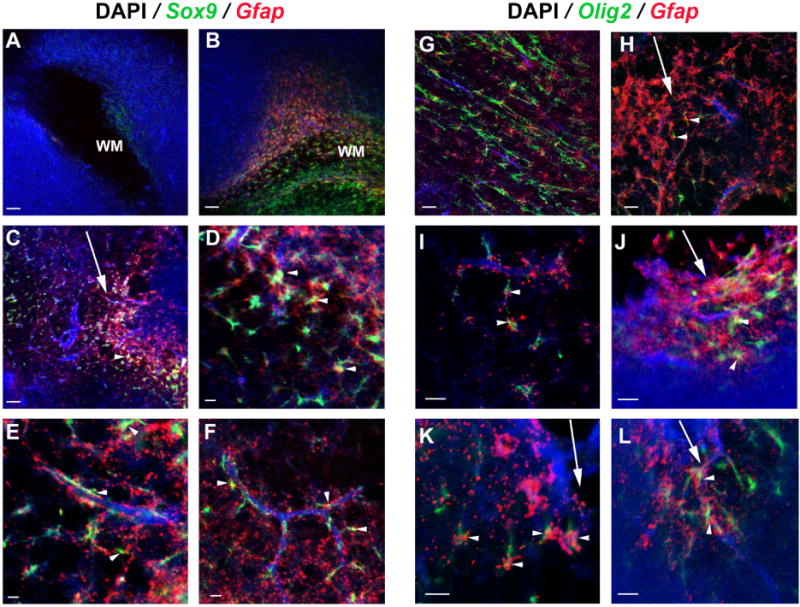

In order to determine whether neural stem cells or glial precursor cells were also responding differently to injuries, the expression patterns of markers of astrocyte precursors (Sox9), oligodendrocytes (Olig2), and neural stem cells (Sox2) were assessed. As shown in Fig. 4, the levels of Olig2, Sox9, and Sox2 mRNAs all increased on the ipsilateral but not the contralateral sides of injured brains. Interestingly, the expression of these precursor and stem cell markers extended beyond the white matter area and mislocalized into the injury site as well. Since the areas where these precursor markers were upregulated coincide with areas of high Gfap expression, we determined whether the population of reactive astrocytes was in part involved in the generation of precursor cells. Because limited information is available regarding mechanisms that could explain these cellular changes in response to injury, it was necessary to distinguish between possible de novo proliferation of precursors or migration of existing precursors/stem cells into the injury areas to replace lost cells. Two-color mRNA fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) showed colocalization of the astrocyte precursor marker Sox9 mRNA with Gfap mRNA-expressing cells in the injury area and surrounding blood vessels (Fig. 5). Colocalization of the oligodendrocyte marker Olig2 mRNA with Gfap mRNA-expressing cells is observed in the injury areas (Fig. 5, arrows) but not in the white matter areas. These findings were further confirmed by evaluating colocalization of GFAP protein detected by immunohistochemistry with Sox9, Sox2, and Olig2 mRNA expression detected by FISH. Many of the Sox9-, Sox2- or Olig2-positive cells were also GFAP-positive (Fig. 6, arrowheads), but importantly, cells were also identified that were expressing either Sox9, Sox2 or Olig2 but were negative for GFAP expression (Fig. 6; arrows).

Fig. 4. Altered expression patterns of glial precursor cell and neural stem cell markers 4 days after stab injury.

Serially adjoining sections (40μm) of the same brain (SW P10) were processed for in situ hybridization of the indicated markers. Contra- and ipsilateral sides are shown. Olig2, Sox9 and Sox2 expression patterns extend from the corpus callosum area into the stab-wound site and cortex. Expression of Sox9 and Sox2 mRNAs are higher in general than that of Olig2. Images are representative of 3 independent brains. Scale bar: 50μm

Fig. 5. Two-color mRNA fluorescent in situ hybridization of Olig2/Gfap expression (A–F) and Olig2/Gfap expression (G–L) in P10-injured animals.

Strong upregulation of Sox9+/Gfap+ cells in the injury-site white matter (B, close up in D) compared with the contralateral side (A). Sox9+/Gfap+ cells are also observed near the injury (C, D) (arrowheads) and associated with adjoining blood vessels (E,F) (arrowheads). Normal white matter areas have no colocalization of Olig2+/Gfap+ expression (G). In the ipsilateral side, Olig2+/Gfap+ cells are found near blood vessels (I) (arrowheads) and around injury sites (H, J, K and L) (arrowheads). Arrows indicate the injury tracks. Similar observations were made for the stab-wound +LPS-treated group (data not shown). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Images are representative of 3 independent brains. Scale bar: 200μm (A-C; G, H) and 50μm (D-F; I-L). WM: white matter.

Fig. 6. Immunohistochemical colocalization of GFAP protein with Sox9, Sox2, and Olig2 expression in the injured regions.

Confocal XY projections of FISH for Sox9, Sox2, and Olig2 mRNAs (green) in injured brains at P10 demonstrate colocalization with the astrocyte marker GFAP (red). ZY projections of the merged pictures through the marked axes (white lines) are shown in the left side panels, respectively. Colocalization (yellow-orange) is indicated in the side panels (arrowhead). Many but not all Sox9-, Sox2- or Olig2-mRNA-positive cells were also GFAP-positive (arrows). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Images are representative of 3 independent brains. Scale bar: 20 μm

To further investigate the contribution of cell proliferation versus a migration mechanism to the changes observed post-injury, we assessed proliferation by injecting BrdU 24 h before collecting the brains at P10 and analyzing incorporation by immunohistochemistry. Gfap mRNA in situ hybridization was performed in nearby sections (Fig. 7). The areas with increased Gfap expression did not exhibit increased proliferation; rather, a general increase in proliferation was observed in brains with stab-wound or stab-wound-plus-LPS injuries in areas where neural stem cells precursors reside (the subventricular zone under the white matter area and in the dentate gyrus area). Since early postnatal GFAP-expressing cells have been demonstrated to give rise to multilineage progeny (Ganat et al., 2006; Guo et al., 2013), we also determined whether there were proliferative GFAP-positive cells in the injured brains. We confirmed co-localization of GFAP and BrdU in the subventricular zone, the dentate gyrus area and in the periphery of the injury site (Fig. 8), in contact with the vasculature (arrows).

Fig. 7. Assessment of cell proliferation after stab-wound brain injury.

BrdU incorporation was used to assess cell proliferation. Animals received a BrdU injection (50mg/kg i.p.) 24h before brains were collected 4 days (P10) after stab-wound injury (SW) and stab-wound injury plus LPS (SW+LPS) treatments. Neighboring sections were processed for mRNA in situ hybridization with Gfap anti-sense probes and anti-BrdU antibodies. Increased numbers of BrdU-positive cells in the VZ (ventricular zone) of the lateral ventricle were observed in both the injured and uninjured side as well as in the dentate gyrus indicating an activation of cell proliferation after brain injury. Arrows indicate injury site. Images are representative of 3 independent brains. Scale bar: 2000 μm.

Fig. 8. Identification of proliferating cell type after injury.

Confocal XY projections of GFAP+ astrocytes (red), dividing cells (BrdU+, green) in the sub-ventricular zone (top panel) and of astrocytes contacting blood vessels (two bottom panels). Animals received a BrdU injection (50mg/kg, i.p.) 3 days after injury, and brains were collected 4 days after injury. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Results indicate that a subpopulation of astrocytes becomes mitotically active after injury (see GFAP+/BrdU+, arrows) cells. Images are representative of 3 independent brains. Scale bar: 25 μm

2.4 Quantitation of injury-induced changes in cell, signaling, and inflammation marker levels by RT-qPCR

To verify the qualitative expression data, a typical experimental RT-qPCR profile from a single mouse litter representing the expression levels for a battery of relevant genes, while comparing mock-injury controls, LPS controls, and ipsilateral and contralateral areas from stab-wound brains with and without LPS treatment, determined four days after injury, are shown in Fig. 9. As expected, elevated levels of Gfap mRNA were present on the ipsilateral side only in stab-wound-alone and stab-wound plus-LPS group brains (Fig. 9), analogous to the in situ expression results for a representative litter depicted in Figs. 2, 3 and 7. Variability in marker expression within and among litters in the same treatment group was observed (Fig. 2). For example, although there appears to be a systemic increase (ipsilateral and contralateral) with the neuronal precursor Dcx mRNA levels in the stab-wound plus-LPS-treated group (Fig. 9), this was not consistent from experiment to experiment. Therefore a comprehensive statistical analysis that included normalizing data for animals from 3-5 independent experiments with 6-9 pups per litter was carried out (Fig. 10), in order to verify the differences between the four treatment paradigms. Additional markers (Aquaporin 4 (Aqp4), glial high affinity glutamate transporter, member 2 (Slc1a2), Mag, Plp1) shown in other studies to be important in brain injury were quantified. Besides Gfap, expression of an astrocytic marker, Aqp4, was also increased on the ipsilateral side only, while expression of other functional genes, i.e. Slc1a2 was unchanged (Fig. 10). The slight decrease in Slc1a2 observed in the contralateral side of the stab-wound plus-LPS-treated group may indicate a possible astrocyte function in response to LPS treatment. Neural precursor marker Sox2 mRNA expression was increased on the ipsilateral side, similar to the Sox2 data in Fig. 4, but was more accentuated in the stab-wound plus-LPS-treated group. There was a mild decrease in expression of the markers Mag and Plp1 in the stab-wound alone group, but both were systemically down-regulated in the oligodendrocytes of the stab-wound plus-LPS-treated group, indicating an acute response to LPS treatment by this cell population.

Fig. 9. RT-qPCR analysis four days after injury.

The results from a typical experiment on a single litter is shown. Postnatal-day-6 (P6) mouse pups underwent sham (C), LPS-alone (LPS), needle cortical stab-wound-alone (SW), or stab-wound-plus-LPS (SW+LPS) treatments. A coronal slice of the brain including the injured area (or control/LPS-alone equivalent area) was dissected on P10 and the ipsilateral (I) and contralateral (C) cerebral lobe sides separated for mRNA extraction and RT-qPCR analysis. Relative normalized expression values were determined using the ΔΔCt (comparative cycle threshold) method for the indicated target genes relative to Ppia (Peptidylprolyl Isomerase) expression in the control, sham-treated brains. For all genes except Gfap, data for injured animals only are shown. Colors indicate contra- and ipsi-lateral sides from the same brain. Values shown are the mean + standard error of data from triplicate determinations.

Fig. 10. Analysis of expression changes of selected genes four days after injury.

Independent RT-qPCR analyses were performed on biological replicates, 3-5 litters of 6-9 pups each, to assess the statistical significance of the observed changes. After normalizing expression levels to Ppia expression in the control, sham-treated brains, contra- (C) and ipsi-lateral (I) RT-qPCRs for each experimental animal (total number of experimental animals is in parentheses; each qPCR was done in triplicate) were analyzed using the paired samples t-test (*p<0.05, **p<0.01). Since no statistical differences between genders were observed in the analyzed genes, animals from both sexes were pooled. Values shown are the mean ± standard deviation of data collected for each condition. In order to compare different experimental animal groups, one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s HSD test was performed. (#p<0.05, ##p<0.01) Mice were injured in the brain cortex with an 18-gauge needle (SW), or injured in the brain cortex with an 18-gauge needle and treated with LPS, 2 μg/g, i.p. (SW+LPS).

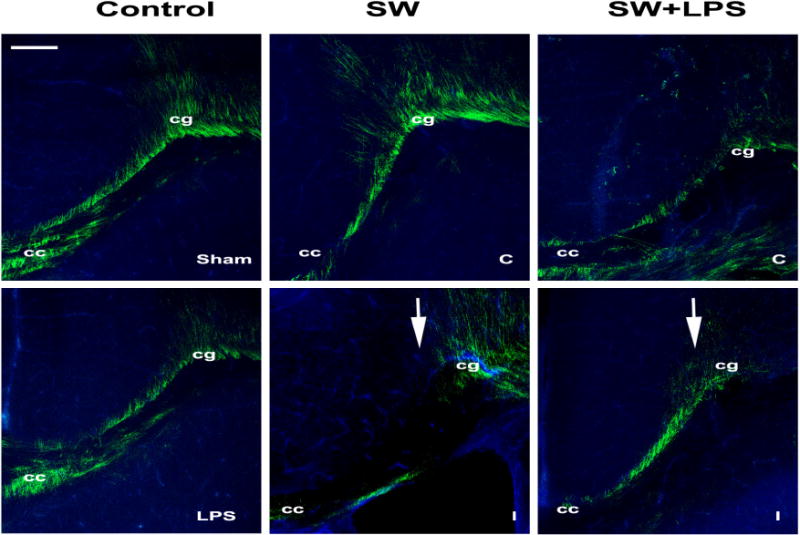

To further ascertain that these differences reflected loss of oligodendrocytes, we stained brain sections from all treatment groups with anti-myelin basic protein (MBP) antibody (Fig. 11). Loss of MBP staining in the ipsi- and contralateral sides of the stab-wound plus LPS brain was observed, in contrast to the stab-wound group for which there is loss of staining only in the injured side (Fig 11).

Fig. 11. Loss of myelin after injury.

Myelin basic protein (MBP) immunostaining of sections from sham and LPS-alone (LPS) controls, and needle cortical stab-wound-alone (SW) or stab-wound-plus-LPS (SW+LPS) treated brains four days after injury (P10);for the latter two groups, contra- (C) and ipsilateral (I) sides are shown. Arrows indicate the SW injury. Cc, corpus callosum; cg cingulum. Scale bar 20μm.

In order to assess the evolution of inflammation over time (P10-P21), levels of Cd68/microsialin, a microglial/macrophage marker upregulated during phagocytic activity (de Beer et al., 2003; Ramprasad et al., 1996) were analyzed and found to be induced in microglia exposed to LPS (Kobayashi et al., 2013) (Fig. 12). While LPS treatment alone did not increase Cd68 expression in the neonatal brain, stab injury did increase Cd68-expression levels on the ipsilateral side at 4 days after injury, commensurate with the increases seen for Gfap expression (Fig. 12). Over time, the microglial response appeared to resolve more completely in the stab-wound-alone group, while it persisted 15 days after injury (to P21) in animals with stab-wound-plus-LPS treatments. We also tested a second marker of microglial activation, Mrc1/Cd206 (Supp. Fig. 1); the results also indicated activation of microglia in the ipsilateral side.

Fig. 12. Evolution of microglial response over time.

A. Relative normalized mRNA expression values were determined for Gfap and Cd68 genes 4-, 8- and 15-days post injury (P10, P15, P21 respectively) relative to Ppia expression in the control, sham-treated brains. Each color represents an individual brain. Values shown are the mean ± standard error of data from triplicate determinations. B. Biological replicates from 3 independent RT-qPCR determinations were analyzed to assess the statistical significance of the observed changes. Cd68 response declines over time after injury (total number of experimental animals is in parentheses; each qPCR was performed in triplicate). Data were analyzed using the paired samples t-test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01) and the values shown are the mean ± standard deviation of the results for each condition.

3. Discussion

Brain injury in premature infants leads to a complex collection of destructive developmental disorders, including major cognitive deficiencies and motor disabilities. Since it is increasingly being recognized that long-term functional impairment is related to perinatal brain injury (Back, 2006; McAdams and Juul, 2012; Volpe, 2009a), we developed an animal model that combines two modes of brain injury: acute trauma that disrupts the blood-brain barrier and remote bacterial infection (simulated by LPS treatment), and analyzed the consequences after injury of each, separately and in combination, by multiple qualitative and quantitative approaches.

Cortical stab injury at P6 produced an acute and severe response characterized (at P10) by enlargement of the ventricle, thinning of the cortex and cavitating periventricular lesions. At the cellular level these lesions exhibited: increased expression of Gfap, a known marker of reactive astrocytes; loss of neurons, as determined by the expression of Tubb3; and loss of Plp1-expressing oligodendrocytes.

Since it is known that during this period of brain development oligodendrocytes as well as astrocytes are not fully mature (Rodricks et al., 2008), we determined how precursor populations were responding to acute stab injury. Interestingly, Sox2-, Sox9-, and Olig2-positive cells were ectopically localized in the injured area, and these transcription factors were partially colocalized with GFAP-positive cells, indicating the possibility of precursors migrating to the injured area. In contrast, after stab injury in the adult rodent brain no upregulation of Sox2 was observed (Heinrich et al., 2014); however overexpression of Sox2 in the injured area showed that this transcription factor could mediate the conversion of oligodendrocyte precursors into neurons (Heinrich et al., 2014). Furthermore, the only areas for which colocalization of GFAP protein and Sox2 have been described in adult brains are those where active neuronal renewal takes place, i.e. the subventricular zone of the lateral ventricles and the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus (Suh et al., 2007). Since we confirmed colocalization of Sox2-positive cells and GFAP expression in the injury zone after perinatal injury, these cells may be multipotent precursors induced in response to injury.

In contrast to the Sox2 pattern, Olig2 has been described as being transiently expressed by immature developing astrocytes of the white matter during neonatal stages and downregulated thereafter (Cai et al., 2007). Thus, the Olig2+/Gfap+ cells ectopically situated after injury may be from a population of immature astrocytes that migrate toward the injured area. The concomitant upregulation of Sox9, also a marker of immature astrocytes, supports that hypothesis. Interestingly, upregulation of Sox9 was also reported in our previous embryonic brain stab injury study in chick (Domowicz et al., 2011), as well as in adult spinal cord crush injury (Gris et al., 2007), and has been speculated to be a regulator of the extracellular matrix accumulation associated with traumatic brain injury (McKillop et al., 2013).

The role of inflammation, as initiated in our model system by LPS treatment, in the course of the response to perinatal brain injury is not fully understood, but we expect that animal models such as ours will provide a means with which to further explore the influence of inflammation on the outcomes of responses to traumatic brain injury. Similarly to the reported effects in LPS-treated pregnant mouse dams (Arsenault et al., 2014), a weight-gain rate decrease was initially observed in neonates treated with a single dose of LPS, independent of receiving a stab injury or not; the weight-gain rate then recovered after about two days and was sustained until maturity (day 21). Similar weight losses and recoveries were reported even for multiple injections of LPS during the perinatal period (Cardoso et al., 2015). Thus, our results are commensurate with previous reports and might reflect the consequences of sickness, fever and dehydration induced by the strong immune response to LPS causing weight loss, which is then recovered after the immune response is under control.

Acute brain-injury responses in subjects receiving a single LPS challenge followed by stab injury did not exhibit significantly increased levels of Gfap and Aqp4 with respect to stab-injury-alone controls, indicating that the astrocytic response to injury is comparable with or without an accompanying immune response (induced by LPS challenge). However, levels of the glutamate transporter Slc1a2 (GLT-1) were compromised systemically by LPS treatment, an indication that astrocytic function may be affected by inflammation. As well, transcriptional levels of two independent oligodendrocyte markers, Mag and Plp1, were affected systemically in the LPS-treated animals. It has been shown that perinatal injection of LPS affects the later ability of the adult brain to respond to demyelinating disease (Cardoso et al., 2015). These prior results, together with our observations, suggest that oligodendrocytes are particularly sensitive (or susceptible) to inflammation. It has been suggested that activation of microglia could drive oligodendrocyte differentiation during CNS remyelination in adult brain (Miron et al., 2013), but it is unclear how this would affect the oligodendrocyte precursor population. Conflicting results regarding the activation of microglia by IP injection of LPS alone in adult mice have been reported (Chen et al., 2012; Hoogland et al., 2015; Terrando et al., 2010). Our results indicate that microglia are not activated by a single LPS injection since the level of the microglia marker Cd68 was not increased with LPS injection alone (Fig 12), but stab injury was followed by strongly increased levels of Cd68 in the injured area. Similarly, levels of Cd206 were increased, which is interesting since this is a marker of M2 microglia types that have been implicated in driving oligodendrocyte differentiation in CNS remyelination models in adults (Miron et al., 2013). Since the levels of Plp1 and Mag were disrupted comparably in the ipsi- and contra-lateral sides of the stab-wound plus LPS group brains, it may be concluded that this effect was not driven by microglia activation. Also, since no changes were observed in any other parameter analyzed during this study following a single LPS injection at P6, is clear that a second brain insult is required for the immune system response to alter brain development. The complexity of the microglia response is reflected in studies of traumatic brain injury followed by LPS treatment in adult animals, where conditioning microglia confer neuroprotection by different possible mechanisms (Bingham et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2014). However, a recent study on microglia development indicated that, based on their transcriptomes, at early postnatal days microglia are in a pre-microglial stage which is different from adult microglia (Matcovitch-Natan et al., 2016). Thus, additional studies on pre-microglial responses to injury modalities and LPS need to be performed to further characterize their response during postnatal development.

Interestingly, some mitotically active GFAP-positive cell populations were identified that might contribute to the repair process of injured tissue. Similar proliferating populations of cells were identified in the periphery of the injury site and the adjacent subventricular zone area that might lead to neuronal replacement ((Buffo et al., 2008) and Fig. 8); thus it is possible that the mitotically active GFAP-positive populations around the injury site may represent a target for future neuronal replacement. Also, during embryogenesis blood vessels are known to provide a supporting environment in regions of neurogenesis (vascular niche) (Bautch and James, 2009; Stubbs et al., 2009), so perhaps it is not surprising to see a large number of BrdU-positive cells associated with blood vessels in the injured areas (Fig. 8).

As shown in this study, multiple mechanisms may contribute to the pathology associated with perinatal brain injury underscoring the need to develop additional comprehensive models to further investigate the underlying mechanisms and to develop novel treatment strategies. Acute injury coupled with systemic inflammation is a useful approach to understand the mechanisms of both the injury itself and the role of inflammation in effecting gliogenesis and repair.

4. Experimental Procedure

4.1 Neonatal stab injury and LPS treatment

P6 pups were anesthetized with isoflurane (initially 3.5% in a mixture of medical air, 1 L/min, and oxygen, 0.1 L/min for induction, followed by 2% at 0.1 L/min for maintenance). The scalp was cleaned with alcohol wipes and a 1.5% solution of lidocaine HCL was applied to the scalp. For animals receiving the stab-wound injury (SW group), a sterile 18 gauge needle was used to create a penetrating brain injury percutaneously into the cortical brain tissue (visual cortex) to a depth of 2 mm. For animals receiving the sham surgery (C group), a sterile 18 gauge needle was used to puncture the skin only. For all animals, a small dab of sterile surgical glue (Vetbond tissue adhesive) was applied to the skin at the site of needle puncture. To mimic an anti-bacterial immune response, pups under anesthesia received 2 μg/g (>600,000 EU/mg) LPS (E. coli, O111 :B4) in an intraperitoneal injection (i.p.) volume of 10 μL, and received a sham-surgery treatment (LPS group) or a stab-wound injury (SW+LPS group) as described above. For identification purposes, all animals were tattooed during anesthesia. For the duration of anesthesia, surgery, and recovery, pups were kept on an isothermal heat source (covered with a sterile drape) to maintain body temperature. Animals were allowed to recover in a warm environment, reunited with their mothers, and brain tissue was collected 4 to 15 days post-injury (P10-P21). Body weight was monitored daily for all treated animals from P6 to P10. Relative body weight was calculated as a function of the average body weight at postnatal day 6 (P6, experiment day) for each litter. Sex was determined using a simplex PCR assay (Clapcote and Roder, 2005).

4.2 mRNA in situ hybridization (ISH) and immunohistochemistry

Control and experimental P10 brains were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and processed for non-radioactive in situ hybridization as described previously (Domowicz et al., 2008; Domowicz et al., 2011). To prepare the digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled RNA probes used for ISH, cDNA fragments from the Glial fibrillary acidic protein (Gfap), Proteolipid protein 1 (Plp1), Myelin basic protein (Mbp), neuronal marker Class III beta-tubulin (Tubb3), Oligodendrocyte transcription factor (Olig2), SRY (sex determining region Y)-box 2 (Sox2), and SRY (sex determining region Y)-box 9 (Sox9) genes were generated by PCR and inserted into pCRII dual-promoter vector plasmids (Invitrogen). Sequencing of the cloned gene fragments was performed with an ABI PRISM 377XL sequencer (Perkin Elmer) by the University of Chicago Cancer Center DNA sequencing facility. Riboprobes incorporating DIG-labeled nucleotides were synthesized from linearized plasmid templates with SP6 or T7 RNA polymerase (Roche). Probed mRNAs were detected after hybridization with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-DIG antibody from Roche. Alkaline phosphatase activity was detected (as blue color production) using BCIP and NBT substrates from Roche. Images of the brains are oriented so that the injured (ipsilateral) cerebral hemisphere is shown on the left and the uninjured (contralateral) side is on the right. For two-color mRNA fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), riboprobes incorporating DIG- and FITC-labeled nucleotides were prepared as described above. Probes were detected after hybridization by treatment with anti-DIG or anti-FITC HRP-conjugated antibody, then developed using tyramide-Cy5 or tyramide-FITC substrates, respectively (Domowicz et al., 2008). Fluorescence was analyzed with a Leica SP8 confocal microscope in the BSD Digital Light Microscopy Core Facility of the University of Chicago Cancer Research Center.

To confirm colocalization of Olig2, Sox2, and Sox9 transcripts in GFAP-positive cells, a combination of FISH and immunohistochemistry was performed on sections prepared as for ISH. FITC labeled riboprobes were used for hybridization and detected with anti-FITC HRP conjugated antibody and developed using tyramide-FITC. Sections were then re-blocked and immunohistochemistry with anti-GFAP antibody (1:200; G-A-5, SIGMA) was performed using an anti-mouse IgG rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody for final detection. 3-D image stacks were acquired by laser scanning confocal microscopy with a Leica SP8 confocal microscope. Images were processed using Image J software.

To assess proliferation, all animal groups were injected with BrdU (50mg/kg, i.p.) 24 h before collecting the brains at P10 and analyzing incorporation by immunohistochemistry using the anti BrdU antibody (1:100; BD Bioscience # 347580)

4.3 Quantitative Real-Time Reverse Transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

After dissecting 3mm coronal sections at the level of the injuries from brains of P10 and P21 mice, contra- and ipsi-lateral cerebral cortical sides were separated and RNA was purified using QIAGEN RNeasy Kit® and quantified. After RNA was reverse transcribed with the High Capacity Reverse Transcription Kit (AppliedBiosystems), RT-qPCRs were performed using the Sso Advanced TM Universal SYBR Green system (Bio-Rad Laboratories) in a CFX-96 realtime PCR instrument (Bio-Rad Laboratories). For each gene, forward and reverse primers were designed using Primer-BLAST (NCBI) and later tested in RT-qPCR; only primer pairs with 90–105% efficiency were utilized. Relative normalized expression values were determined using the ΔΔCt (comparative cycle threshold) methods for the indicated target genes relative to Ppia (peptidylprolyl isomerase A) expression in the control (sham-treated) brains (Pfaffl, 2001).

4.4 Statistical analysis

The data are expressed as means ± standard deviations. Statistical significances were evaluated by the paired-samples Student’s t-test, or one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s HSD (honest significant difference) test. Values of p<0.05 for the null hypothesis were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Research highlights.

Perinatal brain injury leads to ectopic expression of glial and neural stem cell markers.

Concomitant unilateral traumatic injury and lipopolysaccharide exposure in the perinatal brain affect the oligodendrocyte population in both the injured and undamaged sides of the brain.

Multifactorial animal models of perinatal brain injury should lead to better understanding of the complex pathologies associated with cerebral palsy and periventricular leukomalacia in humans.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD: PO1 HD 09402; P30 HD054275). We thank Jim Mensch for helpful comments during manuscript preparation.

Abbreviations

- PVL

periventricular leukomalacia

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- CP

cerebral palsy

- TBI

traumatic brain injury

- FISH

mRNA fluorescent in situ hybridization

- BrdU

5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine

- i.p.

Intraperitoneal

- P

Post-natal day

- WM

white matter

- VZ

ventricular zone

- ΔΔCt method

comparative cycle threshold method

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adelson PD, Kochanek PM. Head injury in children. J Child Neurol. 1998;13:2–15. doi: 10.1177/088307389801300102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arsenault D, St-Amour I, Cisbani G, Rousseau LS, Cicchetti F. The different effects of LPS and poly I:C prenatal immune challenges on the behavior, development and inflammatory responses in pregnant mice and their offspring. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;38:77–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back SA, Luo NL, Borenstein NS, Levine JM, Volpe JJ, Kinney HC. Late oligodendrocyte progenitors coincide with the developmental window of vulnerability for human perinatal white matter injury. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1302–12. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-04-01302.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back SA. Perinatal white matter injury: the changing spectrum of pathology and emerging insights into pathogenetic mechanisms. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2006;12:129–40. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautch VL, James JM. Neurovascular development: The beginning of a beautiful friendship. Cell Adh Migr. 2009;3:199–204. doi: 10.4161/cam.3.2.8397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayly PV, Dikranian KT, Black EE, Young C, Qin YQ, Labruyere J, Olney JW. Spatiotemporal evolution of apoptotic neurodegeneration following traumatic injury to the developing rat brain. Brain Res. 2006;1107:70–81. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.05.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham D, John CM, Levin J, Panter SS, Jarvis GA. Post-injury conditioning with lipopolysaccharide or lipooligosaccharide reduces inflammation in the brain. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2013;256:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittigau P, Sifringer M, Pohl D, Stadthaus D, Ishimaru M, Shimizu H, Ikeda M, Lang D, Speer A, Olney JW, Ikonomidou C. Apoptotic neurodegeneration following trauma is markedly enhanced in the immature brain. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:724–35. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199906)45:6<724::aid-ana6>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch JR. Antenatal events causing neonatal brain injury in premature infants. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2005;34:358–66. doi: 10.1177/0884217505276255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffo A, Rite I, Tripathi P, Lepier A, Colak D, Horn AP, Mori T, Gotz M. Origin and progeny of reactive gliosis: A source of multipotent cells in the injured brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3581–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709002105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J, Chen Y, Cai WH, Hurlock EC, Wu H, Kernie SG, Parada LF, Lu QR. A crucial role for Olig2 in white matter astrocyte development. Development. 2007;134:1887–99. doi: 10.1242/dev.02847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso FL, Herz J, Fernandes A, Rocha J, Sepodes B, Brito MA, McGavern DB, Brites D. Systemic inflammation in early neonatal mice induces transient and lasting neurodegenerative effects. J Neuroinflammation. 2015;12:82. doi: 10.1186/s12974-015-0299-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Jalabi W, Shpargel KB, Farabaugh KT, Dutta R, Yin X, Kidd GJ, Bergmann CC, Stohlman SA, Trapp BD. Lipopolysaccharide-induced microglial activation and neuroprotection against experimental brain injury is independent of hematogenous TLR4. J Neurosci. 2012;32:11706–15. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0730-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Jalabi W, Hu W, Park HJ, Gale JT, Kidd GJ, Bernatowicz R, Gossman ZC, Chen JT, Dutta R, Trapp BD. Microglial displacement of inhibitory synapses provides neuroprotection in the adult brain. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4486. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy B, Darlington RB, Finlay BL. Translating developmental time across mammalian species. Neuroscience. 2001;105:7–17. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00171-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy B, Finlay BL, Darlington RB, Anand KJ. Extrapolating brain development from experimental species to humans. Neurotoxicology. 2007;28:931–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapcote SJ, Roder JC. Simplex PCR assay for sex determination in mice. Biotechniques. 2005;38:702, 704, 706. doi: 10.2144/05385BM05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Beer MC, Zhao Z, Webb NR, van der Westhuyzen DR, de Villiers WJ. Lack of a direct role for macrosialin in oxidized LDL metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:674–85. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M200444-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbing J, Sands J. Comparative aspects of the brain growth spurt. Early Hum Dev. 1979;3:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(79)90022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domowicz MS, Sanders TA, Ragsdale CW, Schwartz NB. Aggrecan is expressed by embryonic brain glia and regulates astrocyte development. Dev Biol. 2008;315:114–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domowicz MS, Henry JG, Wadlington N, Navarro A, Kraig RP, Schwartz NB. Astrocyte precursor response to embryonic brain injury. Brain Res. 2011;1389:35–49. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss B, Tann CJ, Degos V, Sigaut S, Van Steenwinckel J, Schang AL, Kichev A, Robertson NJ, Mallard C, Hagberg H, Gressens P. Inflammation-induced sensitization of the brain in term infants. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2015;57(Suppl 3):17–28. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganat YM, Silbereis J, Cave C, Ngu H, Anderson GM, Ohkubo Y, Ment LR, Vaccarino FM. Early postnatal astroglial cells produce multilineage precursors and neural stem cells in vivo. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8609–21. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2532-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard S, Kadhim H, Beaudet N, Sarret P, Sebire G. Developmental motor deficits induced by combined fetal exposure to lipopolysaccharide and early neonatal hypoxia/ischemia: a novel animal model for cerebral palsy in very premature infants. Neuroscience. 2009;158:673–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard S, Sebire H, Brochu ME, Briota S, Sarret P, Sebire G. Postnatal administration of IL-1 Ra exerts neuroprotective effects following perinatal inflammation and/or hypoxic-ischemic injuries. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26:1331–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gris P, Tighe A, Levin D, Sharma R, Brown A. Transcriptional regulation of scar gene expression in primary astrocytes. Glia. 2007;55:1145–55. doi: 10.1002/glia.20537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z, Wang X, Xiao J, Wang Y, Lu H, Teng J, Wang W. Early postnatal GFAP-expressing cells produce multilineage progeny in cerebrum and astrocytes in cerebellum of adult mice. Brain Res. 2013;1532:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagberg H, Mallard C, Ferriero DM, Vannucci SJ, Levison SW, Vexler ZS, Gressens P. The role of inflammation in perinatal brain injury. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11:192–208. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich C, Bergami M, Gascon S, Lepier A, Vigano F, Dimou L, Sutor B, Berninger B, Gotz M. Sox2-mediated conversion of NG2 glia into induced neurons in the injured adult cerebral cortex. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;3:1000–14. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogland IC, Houbolt C, van Westerloo DJ, van Gool WA, van de Beek D. Systemic inflammation and microglial activation: systematic review of animal experiments. J Neuroinflammation. 2015;12:114. doi: 10.1186/s12974-015-0332-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomidou C, Qin Y, Labruyere J, Kirby C, Olney JW. Prevention of trauma-induced neurodegeneration in infant rat brain. Pediatr Res. 1996;39:1020–7. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199606000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Imagama S, Ohgomori T, Hirano K, Uchimura K, Sakamoto K, Hirakawa A, Takeuchi H, Suzumura A, Ishiguro N, Kadomatsu K. Minocycline selectively inhibits M1 polarization of microglia. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e525. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J, Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering, T 4 million neonatal deaths: when? Where? Why? Lancet. 2005;365:891–900. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson MA, McCusker RH, Kelley KW. Interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme is necessary for development of depression-like behavior following intracerebroventricular administration of lipopolysaccharide to mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2013;10:54. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-10-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lea PMt, Faden AI. Traumatic brain injury: developmental differences in glutamate receptor response and the impact on treatment. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2001;7:235–48. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin HS, Eisenberg HM, Wigg NR, Kobayashi K. Memory and intellectual ability after head injury in children and adolescents. Neurosurgery. 1982;11:668–73. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198211000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallard C, Wang X. Infection-induced vulnerability of perinatal brain injury. Neurol Res Int. 2012;2012:102153. doi: 10.1155/2012/102153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Padilla M. Developmental neuropathology and impact of perinatal brain damage. II: white matter lesions of the neocortex. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56:219–35. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199703000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Padilla M. Developmental neuropathology and impact of perinatal brain damage. III: gray matter lesions of the neocortex. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:407–29. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199905000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matcovitch-Natan O, Winter DR, Giladi A, Vargas Aguilar S, Spinrad A, Sarrazin S, Ben-Yehuda H, David E, Zelada Gonzalez F, Perrin P, Keren-Shaul H, Gury M, Lara-Astaiso D, Thaiss CA, Cohen M, Bahar Halpern K, Baruch K, Deczkowska A, Lorenzo-Vivas E, Itzkovitz S, Elinav E, Sieweke MH, Schwartz M, Amit I. Microglia development follows a stepwise program to regulate brain homeostasis. Science. 2016;353:aad8670. doi: 10.1126/science.aad8670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams RM, Juul SE. The role of cytokines and inflammatory cells in perinatal brain injury. Neurol Res Int. 2012;2012:561494. doi: 10.1155/2012/561494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams RM, Fleiss B, Traudt C, Schwendimann L, Snyder JM, Haynes RL, Natarajan N, Gressens P, Juul SE. Long-Term Neuropathological Changes Associated with Cerebral Palsy in a Nonhuman Primate Model of Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy. Dev Neurosci. 2017;39:124–140. doi: 10.1159/000470903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure MM, Riddle A, Manese M, Luo NL, Rorvik DA, Kelly KA, Barlow CH, Kelly JJ, Vinecore K, Roberts CT, Hohimer AR, Back SA. Cerebral blood flow heterogeneity in preterm sheep: lack of physiologic support for vascular boundary zones in fetal cerebral white matter. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:995–1008. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKillop WM, Dragan M, Schedl A, Brown A. Conditional Sox9 ablation reduces chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan levels and improves motor function following spinal cord injury. Glia. 2013;61:164–77. doi: 10.1002/glia.22424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melville JM, Moss TJ. The immune consequences of preterm birth. Front Neurosci. 2013;7:79. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miron VE, Boyd A, Zhao JW, Yuen TJ, Ruckh JM, Shadrach JL, van Wijngaarden P, Wagers AJ, Williams A, Franklin RJ, ffrench-Constant, C M2 microglia and macrophages drive oligodendrocyte differentiation during CNS remyelination. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1211–8. doi: 10.1038/nn.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti R, Pansiot J, Bettati D, Strazielle N, Ghersi-Egea JF, Damante G, Fleiss B, Titomanlio L, Gressens P. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction in disorders of the developing brain. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:40. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohl D, Bittigau P, Ishimaru MJ, Stadthaus D, Hubner C, Olney JW, Turski L, Ikonomidou C. N-Methyl-D-aspartate antagonists and apoptotic cell death triggered by head trauma in developing rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2508–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramprasad MP, Terpstra V, Kondratenko N, Quehenberger O, Steinberg D. Cell surface expression of mouse macrosialin and human CD68 and their role as macrophage receptors for oxidized low density lipoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14833–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S, Petelenz K, Li Q, Cohen ML, Dechant A, Tabrizi N, Bucek M, Lust D, Miller RH. Developmental changes induced by graded prenatal systemic hypoxic-ischemic insults in rats. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;18:568–81. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodricks CL, Gibbs ME, Jenkin G, Miller SL. The effect of hypoxia at different embryonic ages on impairment of memory ability in chicks. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2008;26:113–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple BD, Blomgren K, Gimlin K, Ferriero DM, Noble-Haeusslein LJ. Brain development in rodents and humans: Identifying benchmarks of maturation and vulnerability to injury across species. Prog Neurobiol. 2013;106–107:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewell MD, Eastwood DM, Wimalasundera N. Managing common symptoms of cerebral palsy in children. BMJ. 2014;349:g5474. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs D, DeProto J, Nie K, Englund C, Mahmud I, Hevner R, Molnar Z. Neurovascular congruence during cerebral cortical development. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19(Suppl 1):i32–41. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh H, Consiglio A, Ray J, Sawai T, D’Amour KA, Gage FH. In vivo fate analysis reveals the multipotent and self-renewal capacities of Sox2+ neural stem cells in the adult hippocampus. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:515–28. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrando N, Rei Fidalgo A, Vizcaychipi M, Cibelli M, Ma D, Monaco C, Feldmann M, Maze M. The impact of IL-1 modulation on the development of lipopolysaccharide-induced cognitive dysfunction. Crit Care. 2010;14:R88. doi: 10.1186/cc9019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titomanlio L, Fernandez-Lopez D, Manganozzi L, Moretti R, Vexler ZS, Gressens P. Pathophysiology and neuroprotection of global and focal perinatal brain injury: lessons from animal models. Pediatr Neurol. 2015;52:566–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe JJ. The encephalopathy of prematurity–brain injury and impaired brain development inextricably intertwined. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2009a;16:167–78. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe JJ. Brain injury in premature infants: a complex amalgam of destructive and developmental disturbances. Lancet Neurol. 2009b;8:110–24. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70294-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker AK, Budac DP, Bisulco S, Lee AW, Smith RA, Beenders B, Kelley KW, Dantzer R. NMDA receptor blockade by ketamine abrogates lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behavior in C57BL/6J mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:1609–16. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman AD, Charvet CJ, Clancy B, Darlington RB, Finlay BL. Modeling transformations of neurodevelopmental sequences across mammalian species. J Neurosci. 2013;33:7368–83. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5746-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yager JY. Neuromethods. 104. Vol. 104. Springer; New York: 2015. Animal Models of Neurodevelopmental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Yakovlev AG, Ota K, Wang G, Movsesyan V, Bao WL, Yoshihara K, Faden AI. Differential expression of apoptotic protease-activating factor-1 and caspase-3 genes and susceptibility to apoptosis during brain development and after traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7439–46. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07439.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.