Abstract

Background and Purpose

Periodontal disease is independently associated with cardiovascular disease. Identification of periodontal disease as a risk factor for incident ischemic stroke raises the possibility that regular dental care utilization may reduce the stroke risk.

Methods

In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (ARIC), pattern of dental visits were classified as regular or episodic dental care users. In the ancillary Dental ARIC study, selected subjects from ARIC underwent full-mouth periodontal measurements collected at six sites per tooth and classified into seven periodontal profile classes (PPC).

Results

In the ARIC study 10,362 stroke-free participants, 584 participants had incident ischemic strokes over a 15-year period. In the Dental ARIC study, 6,736 dentate subjects were assessed for periodontal disease status using PPC with a total of 299 incident ischemic strokes over the 15-year period. The seven levels of PPC showed a trend towards an increased stroke risk (χ2 trend p<0.0001); the incidence rate for ischemic stroke/1,000-person years was 1.29 for PPC-A (health), 2.82 for PPC-B, 4.80 for PPC-C, 3.81 for PPC-D, 3.50 for PPC-E, 4.78 for PPD-F and 5.03 for PPC-G (severe periodontal disease). Periodontal disease was significantly associated with cardioembolic (HR 2.6, 95% CI 1.2–5.6) and thrombotic (HR 2.2, 95% CI 1.3–3.8) stroke subtypes. Regular dental care utilization was associated with lower adjusted stroke risk (HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.63–0.94).

Conclusions

We confirm an independent association between periodontal disease and incident stroke risk, particularly cardioembolic and thrombotic stroke subtype. Further, we report that regular dental care utilization may lower this risk for stroke.

Keywords: Stroke, Cardioembolic, Thrombotic, Periodontal Disease, Atherosclerosis

Subject Terms: Cardiovascular disease, Lifestyle, Primary Prevention, Stroke, Atherosclerosis

BACKGROUND

Periodontal disease is a chronic inflammatory disease caused by bacterial colonization that affects the soft and hard structures that support the teeth.[1] The prevalence of periodontal disease is high, with gingivitis or periodontitis affecting up to 90% of the population worldwide. According to recent findings from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), half of Americans aged 30 or older have periodontitis, the more advanced form of periodontal disease.[2] Periodontitis is associated with an increase in systemic inflammation markers, through chronic low-grade exposure to Gram-negative bacteria[3,4], implicated in the etiology of atherosclerosis and stroke.[5] Observational studies have shown that poor periodontal health status is associated with an increased stroke risk.[6–10] Poor oral hygiene is a major contributor to periodontal disease and thus a potentially modifiable stroke risk factor. An increase in tooth-brushing frequency decreases the concentrations of systemic inflammatory markers levels in the serum.[11] A population based Taiwanese study found that dental prophylaxis or periodontal disease treatment could reduce the incidence of ischemic stroke.[12–13] However, similar data are lacking in the predominantly biracial US population.

Recent reports suggest a rise in the global burden of stroke.[14] Post hoc analyses of prospective–longitudinal and smaller case–control studies have reported an association between periodontal disease and incident stroke.[7] These studies suggest that stroke has a stronger association with periodontal disease than coronary artery disease.[15] Periodontal disease was found to increase the risk stroke by nearly three-fold in a combined analysis of two prospective studies.[16] A more recent meta-analysis of two cohort studies found that periodontal disease increased the risk of incident ischemic strokes by 1.6-fold.[17] Recently, a case–control study confirmed the independent graded association between the severity of periodontal disease and prevalent stroke.[18] If causal, these associations would be of great importance due to the potential that periodontal disease treatment could reduce the stroke risk.

Individual studies have limitations, including the use of many differing definitions of periodontal disease, consideration of potential cofounders such as socioeconomic status, and low statistical power. Additionally, these studies underestimate the prevalence of periodontal disease.[19] Recently, we applied a Latent Class Analysis (LCA) to identify discrete classes of individuals that are discriminated by tooth-level clinical parameters to define seven distinct periodontal profile classes (PPC A–G) and seven distinct tooth profile classes (TPC A–G) ranging from health to severe periodontal disease status,[20] validated in three large cohorts. We applied the periodontal and tooth profile classes using LCA to provide robust periodontal clinical definitions that reflect disease patterns in the population at a subject and tooth level. We examined the relationship between periodontal disease and stroke. as well as the ischemic stroke subtypes.

METHODS

Study Population

The cohort of the ARIC study recruited in 1987–1989 with an aim of studying the causes of atherosclerosis and clinical sequelae.[21] The study enrolled 15,792 participants within the age group of 45–64 identified by probability sampling in a biracial cohort from four US communities. In addition to follow-up visits every three years, participants have been contacted annually by telephone and queried about hospitalizations. The institutional review boards of all participating institutions approved the study and all participants provided written informed consent. All participants, White or African-Americans, who completed the fourth clinic visit (1996–1998) in ARIC (N=11,656), were included in the current study. We excluded those participants (N=1,294) with prevalent stroke or a first ischemic stroke event that occurred before fourth clinical visit. Thus, 10,362 remaining participants were included for dental care utilization analysis.

Dental ARIC, an ancillary study of the ARIC, was conducted at the fourth clinic visit. Data collection included a comprehensive dental examination, questionnaire, and sample collection. Study participants who were edentulous or those requiring antibiotic prophylaxis for periodontal probing were excluded from the Dental ARIC study. Of the 6,793 Dental ARIC participants that underwent periodontal examination at the fourth visit, a total of 6,736 participants without prior stroke were included for distinct periodontal profile class analysis.[20] The ARIC Investigators are willing to share the data used in this manuscript with a researcher for the purposes of reproducing the results, subject to completion of a data use agreement ensuring appropriate protection of the confidentiality of ARIC participants’ data.

Assessment of Dental Care Utilization

The pattern of dental care utilization or dental visits was classified by patient-reported responses to the Dental History Form questionnaire administered at the fourth clinical ARIC study by trained personnel (1996–1998). Participant dental care utilization was classified as regular use (those who sought routine dental care ≥1 time(s) a year) or episodic (only when in discomfort, something needed to be fixed, never, or did not receive regular dental care).

Assessment of Periodontal Profile Class

The analytical approach implemented person-level LCA to identify discrete classes of individuals was based upon 7 tooth-level clinical parameters, including: ≥1 site with interproximal attachment level (IAL) ≥3mm, ≥1 site with probing depth (PD) ≥4mm, extent of bleeding on probing (BOP, dichotomized at 50% or ≥3 sites per tooth), gingival inflammation index14 (GI, dichotomized as GI=0 vs. GI≥1), plaque index15 (PI, dichotomized as PI=0 vs. Pl≥1), the presence/absence of full prosthetic crowns for each tooth, and tooth status presence (present vs. absent).[20] Details of LCA is included in the online supplemental-data.

Adjudication of Stroke Subtypes

Physicians reviewed hospitalization records and stroke diagnoses was made based on a computer algorithm, with any differences adjudicated by a second physician reviewer. All events occurring between the fourth visit (1996–1998) and December 2012 were included as verified ischemic strokes. The study considered incident ischemic strokes and the subjects were censored at the time of the event (recurrent strokes not considered in the analysis). According to criteria adopted from the National Survey of Stroke subtype classification, ischemic strokes were then further classified according to pathogenic subtype as thrombotic brain infarction, lacunar infarction, or cardioembolic stroke.[21–22] Infarct distribution patterns on neuroimaging were not considered per the algorithm.

Other Variables of Interest

Age, sex, race, and additional vascular risk factors such as body mass index (BMI), waist-to-hip ratio, and lipid profile were assessed according to published methods during the fourth ARIC visit (1996–1998).[23] Hypertension was defined as the average of two blood pressure readings at the visit (systolic blood pressure 140 mm HG or higher and diastolic blood pressure 90 mm Hg or higher) or on hypertension medication. Diabetes was measured by a visit-based definition and an interview-based definition. Visit-based diabetes was defined according to serum glucose measurements (fasting blood glucose > 126 mg/dL or > 200 mg/dL if not fasting), a self-reported physician diagnosis of diabetes, or on medication. Participants reported their 3-level education status (basic < 11 years, intermediate 12–16 years, or advanced 17+ years), smoking status, and alcohol use.[24]

Statistical Analysis

Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess crude and adjusted hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval to analyze the association among subjects with periodontal disease and incidence of ischemic stroke, in comparison with those with periodontal health. Similar comparisons were made between regular and episodic dental care users. In both analyses, HR was adjusted for race/center, age, gender, BMI, hypertension, diabetes, LDL level, smoking (3-levels), pack years, and educational level (3-levels). Kaplan Meier survival curve and HR analysis were used to evaluate the incidence of each ischemic stroke subtypes in periodontal disease when compared to periodontal health. All data were analyzed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

In the Dental ARIC study, during the fourth ARIC visit (1996–1998), a subset of 6,736 dentate subjects (mean age ±SD=62.3±5.6, 55% female, 81% white and 19% African-American) were assessed for periodontal disease. The subjects excluded from this cohort had a higher rate of incident stroke (Prior stroke 18.5%, edentulous 7.6%, those with other exclusions 9.0%) compared to those included and completed the dental assessment (4.4%). Baseline characteristics of the dental cohort of the ARIC study population, stratified by PPC-A–G on Visit 4, are shown in Table 1. Participants with higher PPC classes (B through G) were similar in age compared with PPC-A (Health). They included a higher proportion of subjects who were of the male gender and the African-American race. Participants with higher PPC classes (B through G) also had a slightly higher BMI, waist-to hip ratio, and higher proportions of hypertension and diabetes, compared with PPC-A. They also had fewer years of education and were less likely to be current or former alcohol users. The PPC classes (C through G) were more likely to be former and current smokers compared with PPC class A and B. The fasting lipid profiles were similar across the groups. Baseline characteristics of the ARIC study population, divided by dental care utilization, are shown in Table 2. The regular dental care users included a higher proportion of female and White subjects compared to the episodic dental care users. They also had a slightly lower BMI, waist-to hip ratio, and lower proportions of hypertension and diabetes. Additionally, they had more years of education and were more likely to be current or former alcohol users. The regular dental care users were less likely to be former and current smokers compared with the episodic dental care users. The fasting lipid profiles were similar across the groups (not shown). The regular dental care users had a higher proportion of low PPC grades compared to the episodic dental care users suggesting that regular dental care utilization was associated with lower burden of periodontal disease.

Table 1.

Selected Characteristics of the Study Participants, According to Periodontal Profile Class.*

| Value | Periodontal Disease class at baseline | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPC-A (n = 1837) |

PPC-B (n=1036) |

PPC-C (n=689) |

PPC-D (n=793) |

PPC-E (n=993) |

PPC-F (n=890) |

PPC-G (n=498) |

|

| Age (yr) | 61.7±5.5 | 62.3±5.8 | 61.5±5.5 | 63.7±5.6 | 62.8±5.6 | 63.0±5.5 | 61.8±5.7 |

| Sex (%) | |||||||

| Female | 66.5 | 47.2 | 55.4 | 54.9 | 44.6 | 56.9 | 38.4 |

| Male | 33.5 | 52.8 | 44.6 | 45.1 | 55.4 | 43.1 | 61.6 |

| Race (%) | |||||||

| African-American | 3.4 | 3.2 | 72.3 | 18.2 | 1.6 | 34.2 | 45.8 |

| White | 96.6 | 96.8 | 27.7 | 81.8 | 98.4 | 65.8 | 54.2 |

| Body Mass Index† | 27.4±4.8 | 28.3±4.9 | 30.4±6.2 | 28.9±5.3 | 28.2±5.0 | 29.7±6.1 | 29.5±5.9 |

| Waist-to-hip Ratio | 0.92±0.08 | 0.95±0.07 | 0.94±0.07 | 0.96±0.07 | 0.95±0.07 | 0.96±0.07 | 0.96±0.07 |

| Hypertension (%) | 26.0 | 32.1 | 47.4 | 38.3 | 28.1 | 40.0 | 41.1 |

| Diabetes (%) | 8.4 | 12.1 | 21.7 | 15.7 | 10.9 | 18.7 | 21.7 |

| Education (%) | |||||||

| Basic | 5.4 | 8.1 | 23.8 | 16.4 | 5.7 | 28.5 | 23.3 |

| Intermediate | 41.8 | 45.3 | 32.2 | 48.5 | 44.7 | 47.3 | 39.0 |

| Advanced | 52.8 | 46.6 | 44.0 | 35.1 | 49.6 | 24.2 | 37.8 |

| Smoking (%) | |||||||

| Never | 54.6 | 55.2 | 51.0 | 41.2 | 36.4 | 35.8 | 46.8 |

| Former | 38.7 | 38.6 | 36.2 | 42.5 | 46.9 | 42.9 | 37.7 |

| Current | 6.8 | 6.2 | 12.8 | 16.3 | 16.7 | 21.3 | 15.6 |

| Alcohol (%) | |||||||

| Never | 16.0 | 18.8 | 29.7 | 23.8 | 8.4 | 25.0 | 24.1 |

| Former | 21.0 | 25.0 | 34.6 | 28.6 | 21.0 | 35.0 | 32.8 |

| Current | 16.0 | 18.8 | 29.7 | 23.8 | 8.4 | 25.0 | 24.1 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 203.5±34.6 | 200.5±35.5 | 199.0±37.5 | 199.4±36.7 | 201.2±35.2 | 202.1±37.1 | 198.5±37.8 |

| LDL | 120.7±32.2 | 121.6±31.9 | 121.9±35.2 | 121.3±33.2 | 123.3±32.4 | 124.2±34.8 | 124.5±33.8 |

| HDL | 54.1±17.0 | 48.5±16.2 | 52.1±17.2 | 48.1±15.6 | 49.5±16.9 | 48.8±16.1 | 48.3±15.7 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | |||||||

| Median | 125 | 130 | 104 | 127 | 125 | 126 | 110 |

| 25th–75th percentile | 89–174 | 93–186 | 77–144 | 92–179 | 90–171 | 92–177 | 80–150 |

Plus–minus values are means ±standard deviation

The body-mass index =weight (kilogram)/height (meter)2

Table 2.

Selected Characteristics of the Study Participants, According to Frequency of Dental Care Utilization

| Value | Dental Care Utilization | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Regular DDS User (n = 6670) | Episodic DDS User (n=3692) | ||

|

| |||

| Age (yr) | 62.7±5.6 | 63.0±5.7 | |

|

| |||

| Sex (%) | |||

|

| |||

| Female | 57.8 | 52.9 | |

|

| |||

| Male | 42.2 | 47.1 | |

|

| |||

| Race (%) | |||

|

| |||

| African-American | 8.5 | 39.3 | |

|

| |||

| White | 91.5 | 60.7 | |

|

| |||

| Body Mass Index† | 28.1±5.1 | 29.9±6.2 | |

|

| |||

| Waist-to-hip Ratio | 0.94±0.07 | 0.96±0.07 | |

|

| |||

| Hypertension (%) | 33.0 | 44.3 | |

|

| |||

| Diabetes (%) | 11.9 | 23.3 | |

|

| |||

| Education (%) | |||

|

| |||

| Basic | 8.5 | 34.4 | |

|

| |||

| Intermediate | 43.5 | 41.7 | |

|

| |||

| Advanced | 48.0 | 23.9 | |

|

| |||

| Smoking (%) | |||

|

| |||

| Never | 47.7 | 40.8 | |

|

| |||

| Former | 41.3 | 39.4 | |

|

| |||

| Current | 11.0 | 19.8 | |

|

| |||

| Alcohol (%) | |||

|

| |||

| Never | 17.1 | 26.5 | |

|

| |||

| Former | 24.7 | 37.5 | |

|

| |||

| Current | 58.2 | 35.0 | |

|

| |||

| Periodontal status | |||

| PPC-A | 34.4 | 7.8 | |

|

| |||

| PPC-B | 17.7 | 9.1 | |

|

| |||

| PPC-C | 6.7 | 19.8 | |

|

| |||

| PPC-D | 11.6 | 12.3 | |

|

| |||

| PPC-E | 17.7 | 6.8 | |

|

| |||

| PPC-F | 7.4 | 28.9 | |

|

| |||

| PPC-G | 4.5 | 15.4 | |

Plus–minus values are means ±standard deviation

The body-mass index =weight (kilogram)/height (meter)2

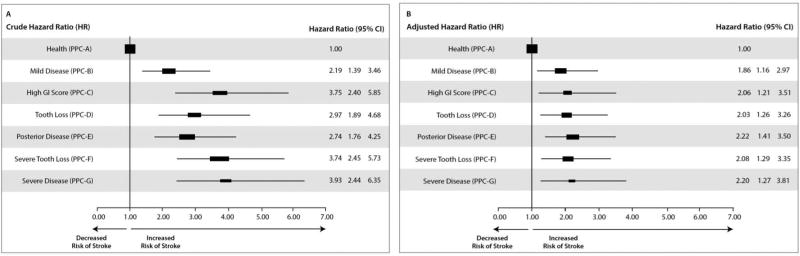

In the Dental ARIC study, during the fourth ARIC visit (1996–1998), a subset of 6,736 dentate subjects (mean age ± SD=62.3±5.6, 55% female, 81% white and 19% African-American) were assessed for periodontal disease. A total of 299 incident ischemic strokes occurred over a median of 15-year follow-up period. The retention of ARIC participants during the follow-up period was high (>90%). Compared with the reference healthy group without periodontal disease (PPC-A), mild periodontal disease or PPC-B (Crude HR 2.19 95% CI 1.39–3.46), high GI score or PPC-C (Crude HR 3.75 95% CI 2.40–5.85), tooth loss or PPC-D (Crude HR 2.97 95% CI 1.89–4.68), posterior disease or PPC-E (Crude HR 2.74 95% CI 1.76–4.25), severe tooth loss or PPC-F (Crude HR 3.74 95% CI 2.45–5.73) and severe periodontal disease or PPC-G (Crude HR 3.93 95% CI 2.44–6.35), had a higher risk for incident ischemic stroke depicted in Figure 1. After adjustment for race/center, age, gender, BMI, hypertension, diabetes, LDL Level, smoking (3-levels), pack years, and education (3-levels), mild periodontal disease or PPC-B (adjusted HR 1.86 95% CI 1.16–2.97), high GI score or PPC-C(Adjusted HR 2.06 95% CI 1.21–3.51), tooth loss or PPC-D (Adjusted HR 2.03 95% CI 1.26–3.26), posterior disease or PPC-E (Adjusted HR 2.22 95% CI 1.41–3.50), severe tooth loss or PPC-F (Adjusted HR 2.08 95% CI 1.29–3.35) and severe periodontal disease or PPC-G (Adjusted HR 2.20 95% CI 1.27–3.81), had a higher risk for incident ischemic stroke. The incidence rate for ischemic stroke/1,000-person years was 1.29 (95% CI 0.92–1.81) for PPC-A, 2.82 (95% CI 2.08–3.83) for PPC-B, 4.80 (95% CI 3.59–6.43) for PPC-C, 3.81 (95% CI 2.80–5.17) for PPC-D, 3.50 (95% CI 2.64–4.65) for PPC-E, 4.78 (95% CI 3.69–6.20) for PPD-F and 5.03 (3.57–7.07) for PPC-G. The PPC- incident stroke association is depicted in a Kaplan-Meier plot in the online data-supplement. The seven levels of PPC showed a trend towards graded association with incident ischemic stroke (χ2 trend p value<0.0001).

Figure 1.

Risk for incident ischemic stroke in the Dental ARIC cohort depicted as crude (A) and adjusted (B) Hazard Ratios for the various classes of periodontal disease: PPC-A or reference healthy group without periodontal disease, PPC-B, or mild periodontal disease, PPC-C or high GI score, PPC-D or tooth loss, PPC-E or posterior disease, PPC-F or severe tooth loss and PPC-G or severe periodontal disease. In panel B Hazard Ratios are adjusted for Race/Center, Age, Gender, BMI, Hypertension, Diabetes, LDL Level, Smoking (3-levels), Pack Years, Education (3-levels).

As shown in Figure 1B, all forms of periodontal disease which are characterized by inflammatory changes are at significantly greater risk than health using this 7-level classification. The inflammatory characteristics differ among the 6 disease classes, but are listed in order of increased mean interproximal attachment loss. In supplemental Figure the incident events are stratified by PPC and the highest rate of events was seen among PPC-C (gingival inflammation) and PPC-G (severe disease) which are the most inflamed classes.[21] Thus, inflammation plays a critical role in defining the risk for incident events as compared to PPC-A (health). What emerges from this investigation is that high gingival inflammation in the absence of severe periodontal disease (PPC-C) and the highly inflamed severe periodontitis class (PPC-G) are at higher risk than those with mild, moderate or posterior disease patterns (all have less inflamed periodontal tissues). These data emphasize the importance of inflammation rather than just the level of attachment as being the main determinant of risk.

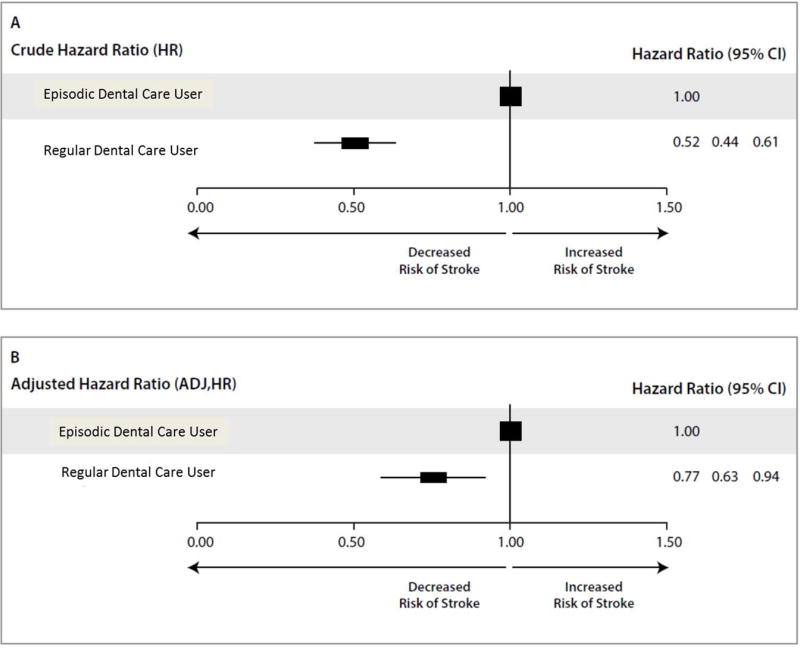

In the main ARIC cohort during the fourth ARIC visit (1996–1998), a total of 11,656 participants (mean age ± SD=62.8±5.6, 56% female, 78% White and 22% African-American) were assessed for dental care utilization. Over a 15-year follow-up period, a total of 584 participants had incident ischemic stroke events. Compared with a reference group of episodic dental care users, regular dental care users had a lower risk for ischemic stroke (Crude HR 0.52 95% CI 0.44–0.61). After adjustment for race/center, age, gender, BMI, hypertension, diabetes, LDL level, smoking, and education, regular dental care use continued to be associated with lower rates of ischemic stroke (adjusted HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.63– 0.94), as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Risk reduction in incident ischemic stroke in the main ARIC cohort depicted as crude (A) and adjusted (B) Hazards Ratio for episodic and regular (reference group for comparison) dental care users, determined at visit 4. In panel B Hazards Ratio is adjusted for Race/Center, Age, Gender, BMI, Hypertension, Diabetes, LDL Level, Smoking (3-levels), Pack Years, Education (3-levels).

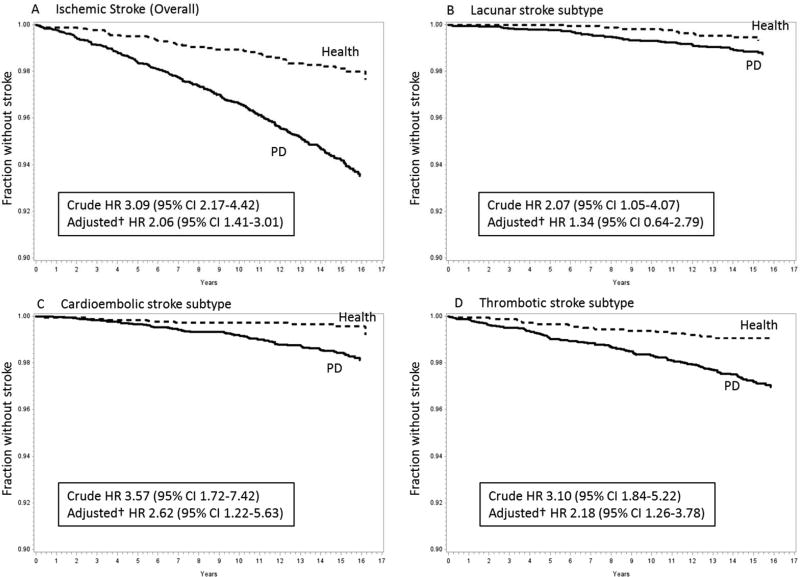

Among the 299 incident ischemic strokes in the dental cohort, 79 were cardioembolic, 140 thrombotic, 61 lacunar, and 19 others. Among the three major stroke subtypes, there was a significant increased hazard of cardioembolic (HR 2.6, 95% CI 1.2–5.6) and thrombotic (HR 2.2, 95% CI 1.3–3.8), but not of lacunar strokes (HR 1.3, 95% CI 0.6–2.8) among study participants with periodontal disease (PPC B–G) compared with those with periodontal health (PPC-A). The association of overall ischemic stroke as well as thrombotic, cardioembolic, or lacunar subtype of stroke and periodontal disease is demonstrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Kaplan Meier curves depicting 15 years’ outcome of (A) incident ischemic stroke (overall), (B) lacunar, (C) cardioembolic and (D) thrombotic stroke subtypes. Inset: Crude Hazard Ratios for ischemic stroke (overall) and stroke subtypes. Hazards Ratio adjusted for Race/Center, Age, Gender, BMI, Hypertension, Diabetes, LDL Level, Smoking (3-levels), Pack Years, Education (3-levels)

DISCUSSION

Periodontal disease is highly prevalent among adults worldwide and is an important public health problem. Assessment of risk profiles for periodontal disease in adults in the United States show male gender, current cigarette smoking, and diabetes are important risk factors for periodontal disease.[25] These findings could enhance recognizable target populations for viable interventions to enhance periodontal health of adults, who may likewise be at an increased risk of ischemic stroke. Our findings show that periodontal disease is an independent risk factor for incident ischemic stroke. It is significant that the high gingival inflammation group, including gingivitis and mild periodontitis but also highly inflamed, likewise had an increased risk of ischemic stroke. Moreover, we report a trend towards a graded association between periodontal disease and incident ischemic stroke. Individual studies, including post-hoc analyses of prospective–longitudinal studies and case–control studies, have reported an association between periodontal disease and incident stroke.[7] It is possible that an increased risk of thrombotic stroke may be secondary to athero-thrombosis in the cervico-cerebral vasculature. The periodontal disease-cardioembolic stroke association may be due to coronary artery disease or atrial fibrillation related to periodontal disease induced inflammation. Contrary to findings noted in prior case-control studies, periodontal disease was not independently associated with lacunar strokes.[26, 27] Possible factors attributable to this difference may be risk factors for lacunar stroke such as age, hypertension, diabetes and low socioeconomic status, were adjusted for in our final hazards ratio model. The periodontal disease-stroke association, if causal, would be of great importance because of the potential that periodontal treatment could reduce the stroke risk.

Dental care is essential for maintaining good oral health, preventing periodontal disease, and identifying symptoms of systemic conditions that might first manifest in the mouth.[28] During 2013, approximately 42% of the US population reported having a dental visit[29] with socioeconomic factors serving as a major determinant for not using regular dental care.[30] A population-based, nationwide study in Taiwan identified periodontal disease as an important risk factor for incident ischemic stroke and showed that periodontal treatment lowered risk of stroke, significantly among young adults.[13] To our knowledge, this would be the first US study to report the independent role of regular dental care in prevention of incident ischemic stroke in a relatively elderly population. This is further validated by the fact that dental care was associated with lower burden of periodontal disease.

Important limitations of this study include the reliance on single periodontal disease assessment, a limited number of incident stroke subtypes, and owing to the observational nature of our investigation, the possibility of residual confounding cannot be eliminated. Socioeconomic factors such as access to care, income, and healthcare behaviors may be potential confounders. However, we adjusted for education levels that in these data serve as a surrogate for the socioeconomic status. Despite these potential limitations, this effort is one of the largest, US-based community studies of periodontal disease, dental care utilization, and ischemic stroke. Subjects excluded raise the possibility of selection bias. However as noted these subjects had a higher rate of incident ischemic stroke compared to those included, suggesting that they are unlikely to negatively influence the study results. Major strengths of this ARIC ancillary study were the use of comprehensive periodontal assessment classified into validated class, adjudication of incident ischemic stroke, stroke subtypes, and rigorous measurement of confounders.

Treatment of periodontitis in pregnant women improved periodontal disease and was safe, but did not significantly alter rates of pregnancy or fetal outcomes.[31] Evidence from randomized controlled trials have established that intensive periodontal treatment improves systemic inflammation, high blood pressure, improves lipid profile[32], and endothelial dysfunction.[33] Therefore, the treatment of PD could plausibly reduce stroke incidence. To the best of our knowledge this hypothesis has not been tested in a randomized clinical trial. The effect of PD treatment on recurrent vascular events in stroke/TIA patients is currently being investigated in PREMIERS trial (NCT02541032). Results may further help verify if periodontal treatment may reduce stroke risk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

All authors contributed to the study concept and design, data analysis, interpretation, manuscript preparation, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Funding

The ARIC Study is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contracts (HHSN268201100005C, HHSN268201100006C, HHSN268201100007C, HHSN268201100008C, HHSN268201100009C, HHSN268201100010C, HHSN268201100011C, and HHSN268201100012C). The Dental ARIC Study was supported by National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research grant R01DE 11551.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Souvik Sen: None

Lauren Giamberardino: None

Kevin Moss: Seeking IP protection for the PPC concept

Thiago Morelli: None

Wayne Rosamond: None

Rebecca Gottesman: Associate Editor AAN

James Beck: Seeking IP protection for the PPC concept

Steven Offenbacher: Seeking IP protection for the PPC concept

References

- 1.Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. Periodontal diseases. Lancet. 2005;366:1809–1820. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67728-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eke PI, Jaramillo F, Thornton-Evans GO, Borgnakke WS. Dental visits among adult Hispanics--BRFSS 1999 and 2006. J Public Health Dent. 2011;71:252–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mustapha IZ, Debrey S, Oladubu M, Ugarte R. Markers of systemic bacterial exposure in periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Periodontol. 2007;78:2289–2302. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.070140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romagna C, Dufour L, Troisgros O, Lorgis L, Richard C, Buet P, et al. Periodontal disease: a new factor associated with the presence of multiple complex coronary lesions. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39:38–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.You Z, Cushman M, Jenny NS, Howard G. Tooth loss, systemic inflammation, and prevalent stroke among participants in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Difference in Stroke (REGARDS) study. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203:615–619. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desvarieux M, Demmer RT, Rundek T, Boden-Albala B, Jacobs DR, Sacco RL, et al. Periodontal microbiota and carotid intima-media thickness: the Oral Infections and Vascular Disease Epidemiology Study (INVEST) Circulation. 2005;111:576–582. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000154582.37101.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scannapieco FA, Bush RB, Paju S. Associations between periodontal disease and risk for atherosclerosis, cardiovascular disease, and stroke. A systemic review. Ann Periodonol. 2003;8:38–53. doi: 10.1902/annals.2003.8.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beck J, Garcia R, Heiss G, Vokonas PS, Offenbacher S. Periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol. 1996;67:1123–1137. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.10s.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Syrjänen J, Peltola J, Valtonen V, Iivanainen M, Kaste M, Huttunen JK. Dental infections in association with cerebral infarction in young and middle-aged men. J Intern Med. 1989;225:179–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1989.tb00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loesche WJ, Schork A, Terpenning MS, Chen YM, Kerr C, Dominguez BL. The relationship between dental disease and cerebral vascular accident in elderly United States veterans. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:161–174. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Oliveira C, Watt R, Hamer M. Toothbrushing, inflammation, and risk of cardiovascular disease: results from Scottish Health Survey. BMJ. 2010;340:c2451. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen ZY, Chiang CH, Huang CC, Chung CM, Chan WL, Huang PH, et al. The association of tooth scaling and decreased cardiovascular disease: a nationwide population-based study. Am J Med. 2012;125:568–575. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee YL, Hu HY, Huang N, Hwang DK, Chou P, Chu D. Dental prophylaxis and periodontal treatment are protective factors to ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2013;44:1026–1030. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feigin VL, Krishnamurthi R, Parmar P, Norrving B, Mensah GA, Bennett DA, et al. UPDATE ON THE GLOBAL BURDEN OF ISCHAEMIC AND HAEMORRHAGIC STROKE IN 1990–2013: THE GBD 2013 STUDY. Neuroepidemiology. 2015;45:161–176. doi: 10.1159/000441085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beck JD, Offenbacher S. Systemic effects of periodontitis: epidemiology of periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol. 2005;76:2089–2100. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.11-S.2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janket SJ, Baird AE, Chuang SK, Jones JA. Meta-analysis of periodontal disease and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95:559–569. doi: 10.1067/moe.2003.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lafon A, Pereira B, Dufour T, Rigouby V, Giroud M, Bejot Y, et al. Periodontal disease and stroke: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21:1155–1161. doi: 10.1111/ene.12415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grau AJ, Becher H, Ziegler CM, Lichy C, Buggle F, Kaiser C, et al. Periodontal disease as a risk factor for ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2004;35:496–501. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000110789.20526.9D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albandar JM. Underestimation of Periodontitis in NHANES Surveys. Journal of Periodontology. 2011;82:337–341. doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.100638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morelli T, Moss KL, Beck J, Preisser JS, Wu D, Divaris K, et al. Derivation and Validation of the Periodontal and Tooth Profile Classification System for Patient Stratification. J Periodontol. 2017;88:153–165. doi: 10.1902/jop.2016.160379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosamond WD, Folsom AR, Chambless LE, Wang CH, McGovern PG, Howard G, et al. Stroke Incidence and Survival among Middle-Aged Adults 9-Year Follow-Up of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Cohort. Stroke. 1999;30:736–743. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.4.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Autenrieth CS, Evenson KR, Yatsuya H, Shahar E, Baggett C, Rosamond W. Association between physical activity and risk of stroke subtypes: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Neuroepidemiology. 2013;40:109–116. doi: 10.1159/000342151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.ARIC Investigators. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Community (ARIC) study: design and objectives. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selvin E, Steffes MW, Zhu H, Matsushita K, Wagenknecht L, Pankow J, et al. Glycated hemoglobin, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk in nondiabetic adults. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:800–811. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, Slade GD, Thornton-Evans GO, Borgnakke WS, et al. Update on Prevalence of Periodontitis in Adults in the United States: NHANES 2009 to 2012. J Periodontol. 2015;86:611–622. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.140520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leira Y, Lopez-Dequidt I, Arias S, Rodriguez-Yanez M, Leira R, Sobrino T, et al. Chronic periodontitis is associated with lacunar infarct: a case-control study. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23:1572–1579. doi: 10.1111/ene.13080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taguchi A, Miki M, Muto A, Kubokawa K, Migita K, Higashi Y, et al. Association between oral health and the risk of lacunar infarction in Japanese adults. Gerontology. 2013;59:499–506. doi: 10.1159/000353707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Institute of Medicine. Improving access to oral health care for vulnerable and underserved populations. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chad D. Meyerhoefer, Irina Panovska and Richard J. Manski. Projections of Dental Care Use Through 2026: Preventive Care to Increase While Treatment Will Decline. Health Affairs. 2016;35:2183–2189. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manski RJ, Hyde JS, Chen H, Moeller JF. Differences Among Older Adults in the Types of Dental Services Used in the United States. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0046958016652523. Inquiry 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michalowicz BS, Hodges JS, DiAngelis AJ, Lupo VR, Novak MJ, Ferguson JE, et al. Treatment of periodontal disease and the risk of preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2006 Nov 2;355:1885–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.D'Aiuto F, Parkar M, Nibali L, Suvan J, Lessem J, Tonetti MS. Periodontal infections cause changes in traditional and novel cardiovascular risk factors: results from a randomized controlled clinical trial. Am Heart J. 2006;151:977–984. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tonetti MS, D'Aiuto F, Nibali L, Donald A, Storry C, Parkar M, et al. Treatment of periodontitis and endothelial function. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:911–920. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.