Abstract

Introduction

Thrombolysis with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is the only FDA approved treatment for patients with acute ischemic stroke, but its use is limited by narrow therapeutic window, selective efficacy, and hemorrhagic complication. In the past two decades, extensive efforts have been undertaken to extend its therapeutic time window and explore alternative thrombolytic agents, but both show little progress. Nanotechnology has emerged as a promising strategy to improve the efficacy and safety of tPA.

Areas covered

We reviewed the biology, thrombolytic mechanism, and pleiotropic functions of tPA in the brain and discussed current applications of various nanocarriers intended for the delivery of tPA for treatment of ischemic stroke. Current challenges and potential further directions of t-PA-based nanothrombolysis in stroke therapy are also discussed.

Expert opinion

Using nanocarriers to deliver tPA offers many advantages to enhance the efficacy and safety of tPA therapy. Further research is needed to characterize the physicochemical characteristics and in vivo behavior of tPA-loaded nanocarriers. Combination of tPA based nanothrombolysis and neuroprotection represents a promising treatment strategy for acute ischemic stroke. Theranostic nanocarriers co-delivered with tPA and imaging agents are also promising for future stroke management.

Keywords: Drug delivery, ischemic stroke, nanocarriers, nanoparticles, nanothrombolysis, thrombolytic therapy, tissue plasminogen activator

1. Introduction

Stroke is a leading cause of death and permanent disability worldwide1. Among all stroke cases, about 87% are ischemic strokes which occur as a result of an obstruction by blood clots within a blood vessel supplying blood to the brain. Acute ischemic stroke consists of an ischemic core of irreversibly damaged tissue and an ischemic penumbra of hypoperfused but potentially salvageable tissue surrounding the ischemic core. Brain cells within the penumbra may remain viable for several hours after stroke onset, because the penumbral zone is supplied with blood by collateral arteries anastomosing with branches of the occluded vessel. Therefore, timely recanalization of the occluded vessel could salvage penumbral tissue and improve neurological function2. Clinically, pharmacological thrombolytics and surgical endovascular therapy have been used to achieve recanalization of occluded vessels for select patients with acute ischemic stroke.

To date, tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) remains the only FDA approved thrombolytic drug for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke, however, its use is limited by the narrow therapeutic time window (<4.5 hours) and by hemorrhagic complication3. In the past two decades, extensive studies have been focused on extending the tPA therapeutic time window beyond 4.5 hours or exploring alternative thrombolytic agents to tPA, whilst most drugs have failed in clinical trials. Currently, only tenecteplase is regarded as a potential alternative to tPA. In patients with acute ischemic stroke, tenecteplase has shown promise in randomized phase II trials and the drug is currently being tested in four phase III clinical trials: NOR-TEST (NCT01949948), TASTE (ACTRN12613000243718), TEMPO-2 (NCT02398656), and TALISMAN (NCT02180204). Newly released result from Phase III NOR-TEST (Last updated May 2017) proved comparable efficacy and safety of tenecteplase vs. alteplase (recombinant human tPA) given <4.5-hours after symptom onset. With the advent of the emerging field of neuronanomedicine, there has been considerable interest in integrating nanomedicine and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke treatment, often referred to as nanothrombolysis. The current issues on clinical use of tPA for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke in patients mainly involve the following aspects: 1) only 10%–25% of cases with intravenous tPA can achieve efficient and permanent recanalization of the occluded vessel, as tPA has a short half-life of around 5–10 min in circulation and only works on the surface of the clot and hardly dissolves larger size or older blood clots; 2) exogenous tPA can cross both the intact and the damaged BBB into ischemic brain tissue, where it may exert neurotoxic effects; 3) intravenous tPA may induce fatal intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) in some cases. However, tPA-based nanothrombolysis is considered to be a promising strategy to address some of the above issues. Nanocarriers could 1) protect tPA in bloodstream thus prolong its half-life; 2) temporally suppress tPA activity in bloodstream thus reduce the risk of systemic bleeding and ICH; 3) target tPA to the occluded vessel thus improve its efficacy; 4) enhance penetration of tPA into clots thus lead to thorough recanalization of the occluded vessel.

In this review, we will discuss the recent advances of tPA-based nanothrombolysis with the use of various nanocarriers. In addition, current challenges and potential further directions of nanothrombolysis in stroke therapy will also be discussed. For preparation of this review, literature searches of MEDLINE, PubMed, and PMC were conducted using different combinations of keywords: “ischemic stroke”; “tissue plasminogen activator or tPA”; “nanothrombolysis”; “nanomedicine”; “nanocarriers”; “nanoparticles”; “liposomes”; “microbubbles”; and “drug delivery”. All cases using nanocarriers to deliver tPA for stroke therapy are included in this review.

2. tPA: biology, thrombolytic mechanism, and pleiotropic functions in the brain

tPA is a serine protease consisting of 527 or 530 amino-acids with 3 or 4 glycosylation sites and 17 disulfide bonds in its secondary structure4. It is released from cells in a single-chain form (sc), but sc-tPA can be cleaved into a mature two-chain form (tc-tPA) by plasmin5 or kallikrein and factor Xa6. Each form of tPA has different glycosylation sites: type I tPA glycosylating at Asn117, Asn 184, and Asn448, and type II tPA glycosylating only at Asn117 and Asn448. Of note, different isoforms of tPA (type I sc-tPA, type I tc-tPA, type II sc-tPA, and type II tc-tPA) may display differential properties in terms of the stability, substrate/receptor affinity, and catalytic efficiency4. Mature tPA contains 5 different functional domains: a finger domain (F), an epidermal growth factor-like domain (EGF), two kringle domains (K1 and K2), and a serine protease proteolytic domain (SP), in an N-terminal end to C-terminal end order. These five domains mediate tPA's multiple bioactivities via interacting with different substrates, binding proteins, and receptors.

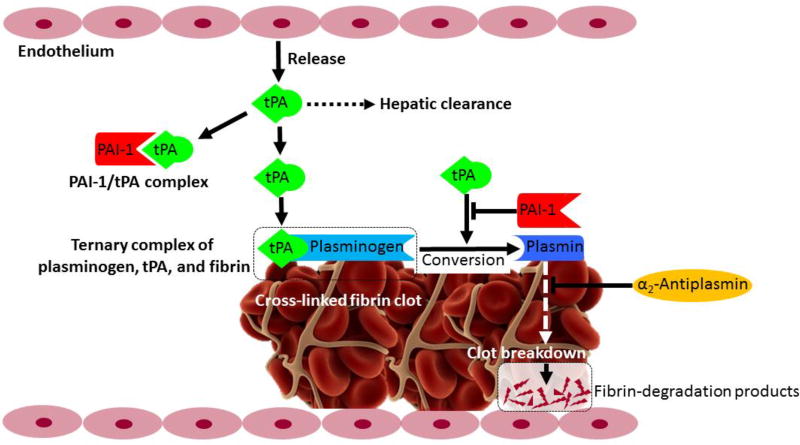

Vascular endothelial cells are thought to be the main source of plasma tPA involved in the breakdown of blood clots (fibrinolysis), which is the major physiological function of tPA in blood. Figure 1 illustrates the in vivo thrombolytic pathway of tPA7. tPA has high affinity and specificity for fibrin. Fibrin binds to tPA’s F and K2 domains, plasminogen binds to tPA’s K2 domain, forming a ternary complex (plasminogen/tPA/fibrin) which catalyzes the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin. Binding of tPA to fibrin may enhance tPA's catalytic activity by 400-fold8. Intravascular thrombi (blood clots) are composed of aggregation of activated platelets and fibrin monomers that are cross-linked through lysine side chains. Plasmin cleaves fibrin, thus breaking down the meshwork of blood clot and causing recanalization of the blocked vessel. The in vivo thrombolytic system could be regulated by α2-antiplasmin and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1). α2-antiplasmin is the main inhibitor of plasmin in the bloodstream, which inhibits plasmin from producing fibrin degradation products. PAI-1 is the main inhibitor of tPA in the bloodstream, which covalently binds to the C-terminal catalytic domain of tPA and forms an inactive PAI-1/tPA complex. Then, the inactive PAI-1/tPA complex can be cleared by liver through low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 (LRP-1) mediated pathway9. Recombinant human tPA (alteplase) was approved by the FDA in 1996 for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Standard dose of tPA recommended by FDA is 0.9 mg/kg bodyweight (10% as bolus and remaining as infusion over 60 min; max 90 mg). tPA maintains a rather short therapeutic window of only 3–4.5 hours after symptom onset and may increase risk of symptomatic ICH, therefore only a few patients could receive (3–8.5%) and benefit (1–2%) from tPA treatment10. Although with limited efficacy and safety, tPA remains the only approved thrombolytic agent for acute ischemic stroke.

Figure 1. tPA-based thrombolytic pathway.

Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), is released by endothelium and circulates in plasma as a inactive complex with plasminogen-activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1). Plasminogen and tPA bind to the surface of fibrin clot, forming a ternary complex (plasminogen/tPA/fibrin), which promotes the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin. Plasmin causes lysis of the cross-linked fibrin into fibrin degradation products. PAI-1 could inhibit the activation of plasminogen induced by tPA. α2-antiplasmin inhibits plasmin from creating fibrin degradation products. Figure was adapted from previous publication7 with permission (© 2014 Bhattacharjee P, Bhattacharyya D. Published in “Fibrinolysis and Thrombolysis” under CC BY 3.0 license. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/57335).

Although best known for its role in fibrinolysis, tPA has also been shown to regulate many nonfibrinolytic functions in the central nervous system (CNS). tPA can be synthesized and released by most of the brain cells. Once released, it can bind to these same cells via different receptors or binding partners. The interaction of tPA with these receptors or binding partners leads to different effects that can be beneficial or deleterious. Previous studies have reported that tPA may increase BBB permeability and brain edema and induce intracerebral hemorrhage in acute ischemic stroke11–14. However, more recent studies have shown potential benefits of tPA for the treatment of ischemic stroke. As evidence of its beneficial effects, tPA has been shown to play a critical role in inhibiting neuronal apoptosis and promoting functional recovery in late phase after stroke15–18. tPA has been shown to exert opposite effects at different time points on the same target19 (e.g., extracellular matrix, NMDA receptors). The beneficial and deleterious effects of tPA in the CNS are time-dependent and involve diverse mechanisms. For readers who are interested in more details about the pleiotropic effects of tPA in the CNS, please read other reviews20–22.

3. Nanocarriers for tPA

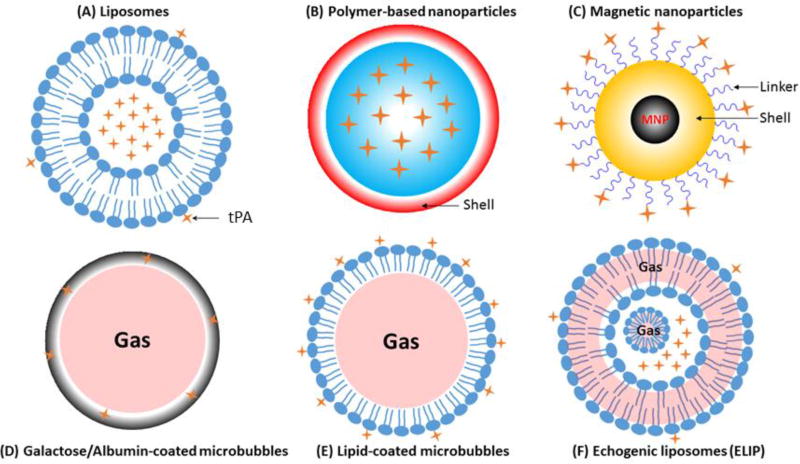

Schematic representations of various nanocarriers discussed in this review are shown in Figure 2. The advantages and disadvantages of various nanocarriers are shown in Table 1, and representative tPA-loaded nanocarriers are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 2. Schematic representation of nanocarriers for tPA-based nanothrombolysis.

-

▪Liposomes (A): tPA can be either incorporated into the inner core or adsorbed onto the outer shell of liposomes; tPA can bind to functionalized liposomes by covalent conjugation or by selective non-covalent metallochelation (His-tagged recombinant tPA);

-

▪Polymer-based nanoparticles (B): tPA can be encapsulated into PLGA or gelatin nanoparticles, and both nanoparticles can be furtherly coated with chitosan (red) or decorated with PEG or targeting moieties;

-

▪Magnetic nanoparticles (C): Most inner core of magnetic nanoparticles is iron oxide (Fe3O4 or γ-Fe2O3), and the surface is mostly coated with organic (e.g., dextran, polyacrylic acid, chitosan) or inorganic (SiO2) shell (yellow). tPA can bind to the shell with either COOH functional groups (blue) or -NH2 functional groups (blue);

-

▪Microbubbles (D–E): microbubbles are microspheres filled with gas (e.g., PFC), and are usually coated with albumin (grey, D) or phospholipids (blue, E) to increase the stability and facilitate tPA binding. When exposed to ultrasound, microbubbles can achieve site-specific delivery of tPA;

-

▪Echogenic liposomes (ELIP) (F): ELIP are liposomes with an outer phospholipid bilayer and a lipid monolayer shell surrounds a gas bubble in the inner aqueous compartment, gas can also locate between the lipid bilayers. tPA can be either incorporated into the inner aqueous compartment or adsorbed onto the outer phospholipid bilayer. Targeted release of tPA can be triggered by ultrasound.

Table 1.

Advantages and disadvantages of nanocarriers in nanothrombolysis

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|

| Liposomes |

|

|

| Polymeric nanoparticles |

|

|

| Magnetic nanoparticles |

|

|

| Micro-bubbles |

|

|

| Echogenic liposomes |

|

|

| Electrostatic supramolecular complexes |

|

|

Table 2.

Summary of representative tPA-loaded nanocarriers

| Nanocarriers type | Composition of carrier | Modification | Model | Key findings | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liposomes | Egg PC, cholesterol, sodium cholesterol-3-sulfate, DSPE-PEG2000 | / | / |

|

28 |

| Liposomes | Egg PC, cholesterol, rhodamine-PE | Anti-actin antibodies | Rat model of embolic focal stroke |

|

29 |

| Liposomes | Soy PC, cholesterol, DOPE, DSPE-PEG2000 | Activated platelets targeted peptide (CQQHHLGGAKQ AGDV) | Inferior vena-cava rat model of thrombosis |

|

31 |

| PLGA nanoparticles (NP) | PLGA, chitosan | GRGD peptide (Gly-Arg-Gly-Asp) | Blood clot-occluded tube model |

|

33 |

| PLGA nanoparticles (NP) | PLGA | / | Mouse Pulmonary Embolism Model; Mouse Ferric Chloride Arterial Injury Model |

|

35 |

| PLGA hydrogel | PLGA, PEG methacrylate, PEG dimethacrylate | / | / |

|

34 |

| Gelatin nanoparticles (NP) | Ethylenediamine cationized gelatins, PEG-gelatin | / | Rabbit thrombosis model |

|

36 |

| Magnetic nanoparticles (MNP) | Fe3O4 | Chitosan coating | Rat embolic model |

|

45 |

| Magnetic nanoparticles (MNP) | Fe3O4 | Silica coating | Pig stented brachial artery model, in vitro flow-through model |

|

46 |

| Magnetic nanoparticles (MNP) | γFe2O3 | Macrophage-derived microvesicles | / |

|

47 |

| Magnetic nanoparticles (MNP) | Iron oxide nanocubes (Fe3O4) | Bovine serum albumin coating | Mouse Ferric Chloride Arterial Injury Model |

|

49 |

| Micro-bubbles (MB) | sulphur hexafluoride (SF6), phospholipid | / | / |

|

68 |

| Echogenic liposomes (ELIP) | DPPC, DOPC, DPPG, cholesterol | / | / |

|

71 |

| Echogenic liposomes (ELIP) | DSPC, DSPE-PEG, cholesterol, perfluoropropane gas | RGD peptide (CGGGRGDF) | Acute thrombotic occlusion model of a rabbit iliofemoral artery |

|

74 |

| Echogenic liposomes (ELIP) | Perfluorocarbon gas (C4F8), DSPC, DSPE-PEG2000 | / | / |

|

79 |

| Electrostatic nanocomplexes | Heparin, albumin-protamine | / | Jugular vein rat thrombosis model |

|

80 |

| Electrostatic nanocomplexes | HSA, thrombin-cleavable peptide | Activated platelets targeting peptide: homing peptide (CQQHHLGGAKQ AGDV) | Rat thrombosis model |

|

82 |

PC: phosphatidylcholine;

Rhodamine-PE: rhodamine-phosphatidyl ethanolamine;

DOPE: dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine;

PLGA: poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid);

DPPC: Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine;

DOPC: dioleoylphosphatidylcholine;

DPPG: 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol;

DSPC: 1, 2-disteoyl-sn-glycero-phosphocholine;

HSA: human serum albumin

3.1. Liposomes

Liposomes, comprising a hydrophobic phospholipid bilayer and a hydrophilic aqueous core, can encapsulate both water-soluble and water-insoluble compounds. Liposomes have been employed as a drug delivery system for tPA since 199523. Heeremans and his team have proved that tPA-loaded liposomes have better anti-thrombolytic effect compared to free tPA24. As the most widely used nanocarriers, liposomes have many advantages as a promising tool for drug delivery: biodegradability, biocompatibility, low immunogenicity, and flexibility in coupling with site-specific ligands. Formulation and preparation methods can influence the characteristics of liposomes, such as loading efficiency, size, zeta potential (surface charge), in vivo circulation time, etc.

3.1.1. Preparation of liposomal tPA

Being a fibrin-specific thrombolytic agent, tPA shows a high affinity to fibrin which could strongly promote the activation of plasminogen by tPA. Due to this specific fibrin-dependent plasminogen activation of tPA, it is supposed that when coupling tPA to the surface of nanoparticles, most of the surface coupled tPA would lose their activity25. However, it was proved that the lipid environment showed no effects on the binding of tPA to fibrin26. Nevertheless, we should avoid utilizing negatively charged components (such as sulphatide or phosphatidylserine) to formulate liposomal tPA, because these components were proved to impair the activation of plasminogen by tPA27. In addition, high intensive sonication and organic solvents should also be avoided to alleviate the degradation and loss of activity of tPA during preparation of liposomal tPA. Moreover, when preparing liposomal tPA via lipid film hydration method, pH and ionic strength can also influence the loading efficiency of liposomal tPA. Because the conformation of tPA may be altered at certain pH and by high ionic strength, moreover, high ionic strength may promote non-specific tPA/liposome interactions, thus impeding the efficient encapsulation of tPA27. Freeze-thawing can promote tPA encapsulation after hydration. Separation of liposomal tPA from free tPA can be conducted by ultracentrifugation (150,000 g, 45 min, at 4 °C). Moreover, lyophilization with cryoprotectant (e.g., trehalose) would promote stability and retention of tPA in liposomes for long-term storage.

3.1.2. PEGylation of liposomal tPA

One of the drawbacks of conventional liposomes is their relatively rapid clearance from circulation by reticuloendothelial system (RES). However, this issue has been addressed via PEGylation, namely modifying liposomes with polyethylene glycol (PEG) to reduce the uptake of liposomes by RES and thus improve the in vivo circulation time. Increased circulation time by PEGylation is also essential to control drug dosage and optimize bio-distribution of liposomal therapeutic agents. PEGylated tPA liposomes with a size of 145 nm and loading efficiency of 21% maintained structure integrity over 45 days at 4 °C, and the half-life of PEGylated liposomal tPA was prolonged to 132.62 min in comparison with that of free tPA (5.87 min) and non-PEGylated liposomal tPA (50.03 min). Whereas, free tPA was rapidly cleared from plasma and the level of tPA in plasma was not detectable even just 1 h after administration28.

3.1.3. Targeting of liposomal tPA

Decorating tPA-loaded liposomes with targeting ligands would optimize the in vivo bio-distribution of liposomal tPA, and lead to targeted thrombolysis. Asahi and co-workers fabricated anti-actin liposomal tPA to reduce tPA induced hemorrhage after focal embolic stroke29. Anti-actin liposomal tPA could target vascular cells exposing intracellular actin cytoskeleton and thereby ameliorate vascular leakage and reseal cellular membranes disrupted by ischemia-reperfusion injury. For active thrombus targeting, a novel peptide with the fibrinogen sequence CQQHHLGGAKQAGDV was used, given that this sequence binds selectively to αIIbβ3 integrin receptors on activated platelets30. Attachment of the αIIbβ3 integrin targeting peptide to PEGylated liposomal tPA was mediated by the standard maleimide coupling reaction. In another study31, Absar et al. encapsulated tPA into PEGylated and non-PEGylated liposomes, respectively, and both liposomes were decorated with the fibrinogen sequence (CQQHHLGGAKQAGDV). This decoration was found to enhance liposomes’ affinity to activated platelets. Consequently, the half-life of tPA has extended from 7 minutes (for free tPA) to 103 and 141 minutes for non-PEGylated and PEGylated liposomes, respectively.

3.2. Polymeric nanoparticles

Both synthetic and natural polymers can be used to fabricate nanoparticles for thrombotic therapy. Besides biocompatibility and biodegradability, synthetic polymers can be easily functionalized and the resulted nanoparticles can be facilely tuned in terms of size, porosity and hydrophobicity. Different from liposomes, the preparation method and the characteristics of polymeric nanoparticles highly depend on polymeric materials. Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), an FDA approved polymer, is a favorable polymer for tPA delivery. PLGA nanoparticles mostly incorporates drugs into their inner core. Natural polymers such as chitosan and gelatin are also favorable alternative materials for tPA delivery. Chitosan, being a hydrophilic cationic polysaccharide, could retain drug by ionic interaction between tPA and the polymer chains.

3.2.1. tPA-loaded PLGA nanoparticles

Wang et al. encapsulated tPA into Fe3O4-based PLGA nanoparticles via double emulsion solvent evaporation method, and further coated with cRGD grafted chitosan (CS)32. The resulted Fe3O4-PLGA-tPA/CS-cRGD showed dual functions: the early detection of a thrombus and also the dynamic monitoring of the thrombolytic efficiency using a clinical MRI scanner. In vitro and in vivo experiments confirmed that Fe3O4-PLGA-tPA/CS-cRGD nanoparticles specifically accumulated on the edge of the thrombus and showed significantly enhanced thrombolysis. Chung et al. constructed tPA-encapsulated PLGA nanoparticles shelled with CS or CS-GRGD with an encapsulation efficacy of 65.5–70.5%, and found that chitosan coated nanoparticles showed accelerated thrombolysis and altered permeation through and clot dissolution patterns in comparison with free tPA in vitro thrombolysis studies33. For the local delivery of tPA, a porous PLGA semi-interpenetrating polymer network (semi-IPN) hydrogel was developed via free-radical polymerization and crosslinking of polyethylene glycol (PEG)-methacrylate through the PLGA network34. tPA incorporated in the hydrogel fully retained its activity, and a steady and sustained release of tPA at the therapeutic range was achieved. Moreover, the release of tPA was facilitated by the porous structure of hydrogel in comparison with dense structure. Korin et al. designed micro-aggregates of poly-lacticglycolic acid nanoparticles coated with tPA, which would rapidly break up and release drug locally upon exposure to the abnormally high shear stress in occluded/stenotic vascular35. Moreover, dose of this shear-activated tPA-nanoparticles required for clot lysis was about 100-times lower than that of free drug for achieving comparable efficacy.

3.2.2. tPA-loaded gelatin nanoparticles

Uesugi et al. developed an ultrasound-responsive gelatin nano-complexes to achieve targeted delivery of tPA36, 37. Cationized gelatins was generated with ethylenediamine before complexing with tPA, and the resulted tPA-cationized gelatin complex was then mixed with PEG-gelatin to form nano-sized complexes with PEG chains on the surface. tPA activity of PEG-modified complexes was significantly suppressed to 45% of original tPA, but could be fully recovered when exposed to ultrasound. Intravenous administration of PEG-modified complexes followed by ultrasound irradiation exhibited complete recanalization in a rabbit thrombosis model, with remarked contrast to complexes administration alone36. Furtherly, Uesugi et al. added zinc acetate to the aqueous solution of gelatin and tPA to form zinc-stabilized gelatin nano-complexes with size of around 100 nm and 57% suppressed tPA activity of the original. The resulted zinc-stabilized gelatin nano-complexes showed prolonged blood circulation and fully recovered tPA activity upon ultrasound irradiation, but no cytotoxicity37.

3.3. Magnetic nanoparticles

Magnetic nanoparticles (MNP) are frequently employed in thrombolytic therapy as drug delivery systems and/or magnetic resonance contrast agents. Currently, iron oxide nanoparticles (IONP) are the most explored MNP due to their biodegradability and their known pathways of metabolism38. Among iron oxides, magnetite (Fe3O4) and maghemite (γ-Fe2O3) are very popular candidates and have suitable magnetic properties for biomedical applications. Synthesis methods have an impressive impact on the magnetic and morphological characteristics of MNP, which has been discussed elsewhere39. IONP become superparamagnetic at room temperature when their radius is below about 15 nm (SPION), and aggregation is a common phenomenon among SPION40. Therefore, bare SPION are usually coated with an organic (e.g., dextran) or inorganic shell (e.g., SiO2) to enhance their colloidal stability and biocompatibility or to offer a facilely functionalized surface. Under the local application of magnetic field, MNP tends to accumulate at a specific site, which is a favorable property for targeted thrombolysis.

Ma et al. developed polyacrylic acid-coated magnetic nanoparticles (PAA-MNP) for tPA delivery, and tPA was covalently immobilized to MNP via carbodiimide-mediated amide bond formation, leading to a reproducible and effective targeted thrombolysis with <20% of a standard dose of tPA in a rat embolic model41. Other coating molecules such as carboxymethyl dextran42, silica43, poly [aniline-co-N-(1-one-butyric acid) aniline]44, and chitosan45 were also utilized to decorate tPA-loaded MNP, and tPA was conjugated on the particle surface with either -COOH or -NH2 functional groups. The resulted tPA-loaded MNP showed enhanced storage stability and almost full retention of thrombolytic activity. Especially, the loading efficiency of MNP coated with poly [aniline-co-N-(1-one-butyric acid) aniline] is 0.267 mg of tPA per mg of MNP, which was much higher than that of CMD-MNP (0.05 mg tPA/mg CMD-MNP), PAA-MNP (0.077 mg tPA/mg PAAMNP), and SiO2-MNP (0.1 mg tPA/mg SiO2-MNP). High loading of tPA per MNP can reduce the amount of MNP required for the delivery of a specific dosage of tPA and thus reduce the potential toxicity44. Kempe et al. fabricated MNP (Fe3O4) with the size-range of 10–30 nm by oxidation-precipitation method for implant-assisted magnetic tPA targeting in thrombolytic therapy, tPA was covalently bound to silanized MNP that was pre-activated with either N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide or tresyl chloride46.

In addition to the above conventional MNP, novel approaches have been employed to fabricate MNP for the efficient delivery of tPA. Silva et al. engineered macrophage-derived microvesicles to enclose tPA and co-encapsulate magnetic iron oxide (γFe2O3) nanoparticles. They found that co-incubation of iron oxide nanoparticles did not influence the uptake of tPA, and tPA localized at the cytoplasm after endocytosis. This novel hybrid cell microvesicles could be manipulated by magnetic force for targeting delivery of tPA to blood clots47. Lately, Tadayon et al. developed an extracellular biosynthesis of nanoparticles (CuNP) for the simultaneously targeted delivery of tPA and streptokinase (SK)48. tPA and SK were conjugated with these CuNP nanoparticles. Effective thrombolysis with magnet-guided SiO2-CuNP-tPA-SK was demonstrated in a rat embolism model. tPA when immobilized onto 20 nm clustered iron oxide nanocubes (NCs) displayed 3 orders of magnitude enhanced clot dissolution, and could recanalize occluded vessels within a few minutes by dissolving clots via both direct interaction of tPA with the fibrin network (chemical lysis) and localized hyperthermia upon stimulation of superparamagnetic NCs with alternating magnetic fields(mechanical lysis)49. Iron oxide (Fe3O4) nanorods loaded with 6% tPA were demonstrated to release tPA within ~30 min and showed improved thrombolytic efficiency under magnetic guidance50.

3.4. Micro-bubbles and echogenic liposomes triggered by ultrasound

Ultrasound can be used either alone or as an adjuvant therapy for thrombolytic treatment51. Thrombolytic effect of ultrasound was proposed to be attributed to two different approaches: mechanical fragmentation of the clot and enhanced transport of thrombolytic agents to thrombus via static52 and perfusion53 systems. In spite of the various advantages of ultrasound, using it alone has some drawbacks: inducement of embolization due to the fragmentation of clot54; mechanical vascular impairment54; and re-occlusion caused by activation of platelets. As a result, ultrasound is now used as an adjuvant for thrombolytic therapy, namely sonothrombolysis55. For further improvement of ultrasound enhanced-thrombolysis, the concept of using contrast agents for better imaging and delivery of thrombolytic agents was tested. Micro-bubbles and echogenic liposomes are two principle examples of contrast agents.

Based on the promising effect of ultrasound in increasing the efficiency of intravenous tPA, several clinical studies have been carried out which demonstrated the enhanced efficacy of ultrasound-based tPA thrombolysis in stroke patients56–58. It was found in CLOTBUST, a phase II multicenter randomized trial, that ultrasound in combination with tPA did induce recanalization or dramatic clinical improvement in 42% of treated versus 29% of control patients57. Standard dosage used in CLOTBUST was: standard intravenous tPA (0.9 mg/kg body weight, 10 % as bolus, the remainder over 1 hour) in combination with 2-hours continuous 2-MHz diagnostic transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasound. Moreover, it has been found that lower ultrasound frequencies (e.g., 300 kHz, in kilohertz) can cause higher rates of intracerebral hemorrhage59, whereas the diagnostic frequencies (e.g.,2-MHz, in megahertz) show no such side effect and are safe enough to be used in humans57, 58, 60.

3.4.1. Micro-bubbles

Micro-bubbles (MB) are tiny gas- or air-filled microspheres and were first used as contrast agents for imaging due to their acoustic characteristics55. The mechanism by which MB enhance ultrasound-accelerated thrombolysis was attributed to stable and inertial cavitation, as these MB act as nuclei for cavitation decreasing the amount of energy required for the cavitation61. Stable cavitation leads to oscillations of MB, resulting in micro-streaming and erosion of clot surface which enhances the penetration of thrombolytic agents into clots62. Inertial cavitation is induced by increasing the acoustic power on MB, leading to an explosion which emits the absorbed energy63. The first mechanism is mechanical, and the second improves permeation of thrombolytic agent into the clot.

The effect of MB on thrombolysis depends on many factors, such as bubble size, concentration of MB in the clot area, and stability of MB in bloodstream61. The first generation of MB is air-filled and encapsulated by a weak shell, which can be cleared rapidly from systemic circulation due to their low stability. In addition, their relatively large size reduces their ability to cross lung circulation and reach the thrombus64. As a result, the second generation of MB was introduced by filling MB with a high molecular weight gas (e.g., perfluorocarbon gas) and also coating MB by phospholipids (SonoVue®) or albumin (Albunex®). Normally, air-filled MB have a mean size of around a micron, whilst MB comprised of perfluorocarbon (PFC) gas have a mean diameter of about 250 nm and a longer residence time in the blood. There are many combination of ultrasound activated MB with intravenous tPA for ischemic stroke treatment, while tPA-loaded MB are relatively less reported. MB loaded with tPA and modified with Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser tetrapeptide (RGDS) was prepared by lyopyilization, in vitro studies and an in vivo rabbit femoral artery thrombus model proved that the resulted targeted tPA-loaded MB showed reduced tPA dosage, satisfactory thrombolytic efficacy, and potentially decreased hemorrhagic risk under ultrasound exposure65, 66. Lately, coaxial electrohydrodynamic atomization technique was employed to fabricate tPA-loaded MB for potential theranostic application, using sulphur hexafluoride (SF6) as the core and lipid as the shell material generated MB with an average minimum size of ~8 μm and less bubble aggregation67, maximum tPA payload can reach 109.89 μg tPA/ml MB and tPA maintained at lease ~80% of its activity68.

3.4.2. Echogenic liposomes

The second example of contrast agent is echogenic liposomes (ELIP). Echogenic liposomes are multifunctional phospholipid-bilayer encapsulated vesicles, which can be used as contrast agent for sonography and drug delivery systems as well69, 70. When encapsulating gas into liposomes, the gas locates either between the lipid bilayer or within the inner compartment of liposomes. For tPA-loaded ELIP, the overall entrapment efficiency of tPA into liposomes was about 50%. Of that 50%, around 35% of the loaded tPA were associated with the lipid bilayer and only 15% were encapsulated within the inner compartment of liposomes71. Exposure of ELIP to ultrasound can induce disruption of the lipid shell and hence trigger drug release70. As a result, under the guidance of ultrasound, tPA-loaded ELIP (t-ELIP) can release tPA locally thus increase concentration of tPA in the area of thrombus, reduce the required therapeutic dose of tPA and consequently lower the risk of ICH. Moreover, the gas encapsulated into t-ELIP can exert a cavitation-related mechanism, as explained earlier, leading to enhanced thrombolytic effects72.

A number of ELIP have been developed to co-encapsulate cavitation nuclei and tPA to promote ultrasound reflectivity and to enable targeted delivery of tPA. Results from these studies showed that: 1) tPA released from ELIP had similar enzymatic activity as free tPA69; 2) encapsulating PFC gas other than air could enhance ultrasound-mediated stable cavitation activity and increase thrombolytic efficacy73, 74; 3) thrombolytic activity of tPA loaded with ELIP was comparable to that of tPA alone, and addition of 120 kHz ultrasound significantly enhanced thrombolytic efficacy of both tPA and tPA-loaded ELIP75; 4) entrapment of tPA into ELIP showed effective clot lysis and targeted ultrasound-facilitated drug release75; 5) fibrin binding of tPA loaded with ELIP was twice that of free tPA76, and PPACK-inactivated tPA still maintained fibrin-binding activity77, which can be employed as a fibrin-targeting moiety for ELIP-based thrombolysis.

Hagisawa et al. developed PFC- and tPA-containing ELIP, and furtherly modified ELIP with a RGD peptide. Intravenous injection of RGD-modified ELIP into rabbits with thrombus in iliofemoral arteries can achieve a higher recanalization rate (nine out of ten rabbits) when ultrasound was applied, compared with that of animals receiving non-RGD-modified ELIP (two out of ten rabbits) or tPA monotherapy (four out of ten rabbits)69, 74. Conventional manufacturing techniques of ELIP (sonication-lyophilization-rehydration method78) produce a polydisperse ELIP population with only a small percentage of particles containing microbubbles. Lately, a microfluidic flow-focusing device was used to generate monodisperse tPA and PFC co-loaded ELIP (μtELIP)79, which improved encapsulation efficiency of both tPA and PFC microbubbles into echogenic liposomes. The resulted μtELIP had a mean diameter of 5 μm, a resonance frequency of 2.2 MHz, and were found to be stable for at least 30 min in 0.5 % bovine serum albumin. Additionally, 35 % of μtELIP were estimated to contain PFC microbubbles, an order of magnitude higher than that reported previously for batch-produced tPA-loaded ELIP.

3.5. Camouflaged-tPA electrostatic supramolecular complexes

Absar et al. developed two similar electrostatic supramolecular complexes to camouflage tPA’s thrombolytic activity during circulation and recover its activity at thrombus site: 1) albumin-camouflaged and heparin-triggered strategy80, 81; 2) albumin-camouflaged and thrombin-triggered strategy82. Both strategies showed efficient targeted thrombolysis and reduced risk of hemorrhage. In the first strategy, tPA was conjugated with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) to form oligoanion-modified tPA (LMWH-tPA), and albumin was conjugated with protamine separately to form albumin-protamine. Then complexion of these two conjugates can form a reversible electrostatic complex (albumin-protamine/LMWH-tPA) through the electrostatic interaction of protamine and heparin80. Alternatively, a relatively inert oligoanion (polyglutamate) could replace bioactive LMWH to avoid any potential side effects, and human serum albumin (HSA) could replace albumin, thus forming a reversible electrostatic complex of HSA-protamine/polyglutamate-tPA81. tPA in both reversible electrostatic complexes can be camouflaged by HSA or albumin via creating a steric hindrance against systemic plasminogen and tPA-binding macromolecules in the plasma, thus tPA’s thrombolytic activity can also be masked during circulation. When decorated albumin or HSA with a homing peptide (CQQHHLGGAKQAGDV) which binds with GPIIb/IIIa expressed on activated platelets, the generated reversible electrostatic complex can target to activated platelets, and subsequent administration of heparin can fully recover tPA’s activity to achieve targeted thrombolysis.

In the second strategy (albumin-camouflaged and thrombin-triggered system), tPA was camouflaged with HSA linked by a thrombin-cleavable peptide (GFPRGFPAGGCtPA), and the surface of albumin molecule was decorated with a homing peptide (CQQHHLGGAKQAGDV) that binds with GPIIb/IIIa expressed on activated platelets. Such system suppressed 75% of tPA's activity during circulation but regenerated its thrombolytic efficacy to ~90% that of native tPA upon contacting with thrombin present on the thrombus. This approach is an efficient delivery system for tPA working in an on/off triggered manner82.

4. Conclusion

To date, intravenous tPA remains the only gold standard treatment for acute ischemic stroke, although tenecteplase is tested as a potential alternative for tPA. As compared with the classic intravenous tPA, using nanocarriers for targeted delivery of tPA to intravascular thrombus shows great promise to improve the efficacy and safety of tPA for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Recent studies have demonstrated that nanocarriers, such as liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, magnetic nanoparticles, micro-bubbles and echogenic liposomes, offer great benefits for tPA-based thrombolytic therapy either alone or in combination with ultrasound or magnetic force.

5. Expert opinion

Using nanocarriers to deliver tPA in stroke therapy offers many advantages to improve thrombolytic efficiency and to overcome many problems associated with the classic intravenous tPA. For instance, incorporating tPA into nanocarriers can protect tPA from inactivation by PAI-1 in bloodstream, prolong circulation time, thus can achieve effective thrombolysis with a lower-than-standard dose of intravenous tPA. Moreover, nanocarriers can camouflage the thrombolytic activity of tPA during circulation and thus reduce risk of systemic bleeding and ICH. More interestingly, targeted delivery of tPA to the thrombus site can be achieved by modifying nanocarriers with targeting moieties (peptides, antibodies, biomarkers of blood clots) or by ultrasound/magnetic force irradiation, and such targeted nanothrombolysis can accelerate thrombolysis and reduce risk of systemic bleeding via enhancing the accumulation of tPA at the clot surface. When combined with ultrasound or magnetic force, targeted nanothrombolysis can improve recanalization rate by enhancing penetration of tPA into large/older clots. Among the various nanocarriers, microbubbles are the most promising for tPA-based nanothrombolysis nanocarriers with high clinical translation potential, given to the encouraging results from clinical trials of microbubbles combined with ultrasound and intravenous tPA. Further validation of the efficiency and safety of tPA-based nanothrombolysis is awaited in clinic.

Although tPA-based nanothrombolysis opens a new strategy for stroke therapy, there are also potential risks and challenges associated with this novel strategy. For instance, the main purpose of tPA therapy in ischemic stroke is to dissolve an intravascular thrombus, so tPA-loaded nanocarriers should be maintained within the intravascular compartment to exert its thrombolytic effect. However, compromised BBB integrity following ischemia can cause the leakage of tPA-loaded nanocarriers into the brain parenchyma. If tPA leaks into the parenchyma, it causes neurotoxicity through the NMDA receptors and even exacerbates hemorrhagic transformation, although little is known about the effects of the leaked nanocarriers in the brain. Therefore, a major challenge to the successful translation of tPA-based nanothrombolysis involves preventing/attenuating the leakage of tPA-loaded nanocarrier into the brain, which are till now rarely investigated. Modifying tPA-loaded nanocarriers with moieties that can directly target blood clots would be an effective strategy to reduce tPA leakage. In addition, using nanocarriers with appropriate particle size or choosing appropriate administration time might also help to reduce the leakage of tPA-loaded nanocarriers.

Another main challenge of nanothrombolysis is that nanocarriers may alter the pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) of tPA, however, these aspects have rarely been investigated. Other factors also need to be optimally selected for the successful translation of nanothrombolysis. These factors include particle size, dispersity, stability, encapsulation efficiency, release profiles, bio-distribution, biocompatibility of materials used to fabricate nanocarriers, and nanotoxicity, which are also current challenges that need to overcome. For example, in the case of particle size, the particle size of nanocarriers should be appropriate, neither too big nor too small. Large-size nanocarriers might be too big to go through microvessels, thus resulting in insufficient microvascular thrombolysis. On the other hand, the clearance rate of very small nanocarriers is high, thus making targeted nanothrombolysis ineffective. In the case of nanotoxicity83, some nanocarriers might disrupt the body’s homeostasis, and conjugated targeting moieties may induce immunological response. Therefore, selecting biocompatible materials to fabricate nanocarriers with appropriate size is important in the development of nanothrombolysis. Additionally, adopting the appropriate animal models is also important for preclinical research of nanothrombolysis. Among various available animal stroke models, the embolic model of middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo) in the rat is the most commonly used stroke model for thrombolytic stroke studies, as its thrombolytic reperfusion time window and hemorrhagic transformation closely mimic clinical situation84, 85. Therapeutic efficacy of tPA-based nanothrombolysis should be evaluated firstly in small animal stroke models, then further validated in larger species such as nonhuman primates before moving on to the clinical trials. Using animal models coupled with a higher risk factor of stroke (e.g., hypertension, obesity, diabetes, and aging) is also highly recommended.

Nanotechnology offers a promising platform to integrate different therapeutic modalities for stroke combination therapy. Currently, managing both of the primary damage (salvaging the ischemic penumbra) and the secondary neuronal damage stands for comprehensive therapeutics for stroke. Using nanocarriers to co-deliver tPA and neuroprotective agents could not only extend therapeutic time window of tPA86–89 but also improve long-term neurological outcomes through synergistic mechanisms. tPA and the other drug can be encapsulated into nanocarriers at appropriate drug ratio and released in a controlled manner, thus lead to synergistic efficacy with fewer side effects for stroke treatment44. Intriguingly, some nanocarriers (e.g., carbon nanotubes90, 91) themselves have neuroprotective capacity, can enhance neuron survival and motor function recovery, which can be used to deliver tPA to achieve both thrombolytic and neuroprotective effects.

In recent years, endovascular recanalization therapy (ERT) has emerged as the new gold standard of care in acute ischemic stroke. ERT has an advantage of a higher recanalization rate for proximal intracranial artery occlusion that is usually resistant to intravenous tPA92. It has been suggested that in patients with severe stroke and documented proximal intracranial artery occlusion, intravenous tPA should be promptly followed by endovascular therapy92. The combination of ERT and tPA-based nanothrombolysis may represent a promising strategy for stroke therapy, which may greatly improve therapeutic efficacy and allow more stroke patients accessible to treatments.

Besides, developing theranostic nanocarriers is another future direction for tPA-based nanothombolysis, because they have significant implications for both treatment and diagnosis. Nanocarriers co-loaded with tPA and imaging agents (e.g., near infrared fluorescent probes, gadolinium complexes, gold, iron oxides or perfluorocarbon) are theranostic, which could not only achieve real-time visualization of drug delivery but also evaluate treatment outcome (monitoring infarct volume) using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) imaging.

Article Highlights.

To date, intravenous tPA remains the only FDA approved thrombolytic drug treatment for acute ischemic stroke, despite its limitations in both efficacy and safety. Tectophase is a potential alternative for tPA.

Incorporating tPA into nanocarriers can 1) prolong the circulation time of tPA, thus achieve effective thrombolysis at a lower-than-standard dose; 2) temporally camouflage the thrombolytic activity of tPA during circulation thus reduce risk of intracerebral hemorrhage; 3) achieve targeted thrombolysis by modifying nanocarriers with targeting moieties or by ultrasound/magnetic force irradiation.

Using nanocarriers to co-deliver tPA and neuroprotective agents shows great promise in extending treatment time window of tPA and improving therapeutic efficacy through synergistic actions.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants NS088719 and NS089991 (Dr. Li).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015 Jan;131(4):e29–322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bivard A, Lin L, Parsonsb MW. Review of stroke thrombolytics. J Stroke. 2013 May;15(2):90–8. doi: 10.5853/jos.2013.15.2.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3••.Marshall RS. Progress in Intravenous Thrombolytic Therapy for Acute Stroke. JAMA Neurol. 2015 Aug;72(8):928–34. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.0835. Excellent review that present a historical prospective and current trends in thrombolytic therapy, focusing on characteristics of drugs that have worked and clinical trials that are moving the field forward. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chevilley A, Lesept F, Lenoir S, Ali C, Parcq J, Vivien D. Impacts of tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) on neuronal survival. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:415. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallen P, Bergsdorf N, Ranby M. Purification and identification of two structural variants of porcine tissue plasminogen activator by affinity adsorption on fibrin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982 Nov;719(2):318–28. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(82)90105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ichinose A, Kisiel W, Fujikawa K. Proteolytic activation of tissue plasminogen activator by plasma and tissue enzymes. FEBS Lett. 1984 Oct 01;175(2):412–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)80779-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhattacharjee P, Bhattacharyya D. Fibrinolysis and Thrombolysis. Rijeka: InTech; 2014. An Insight into the Abnormal Fibrin Clots — Its Pathophysiological Roles. Ch. 0. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collen D. Molecular mechanisms of fibrinolysis and their application to fibrin-specific thrombolytic therapy. J Cell Biochem. 1987 Feb;33(2):77–86. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240330202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yepes M, Sandkvist M, Moore EG, Bugge TH, Strickland DK, Lawrence DA. Tissue-type plasminogen activator induces opening of the blood-brain barrier via the LDL receptor-related protein. J Clin Invest. 2003 Nov;112(10):1533–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI19212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joshi MD. Advances in Nanomedicine for Treatment of Stroke. International Journal of Nanomedicine and Nanosurgery. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kidwell CS, Latour L, Saver JL, Alger JR, Starkman S, Duckwiler G, et al. Thrombolytic toxicity: blood brain barrier disruption in human ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;25(4):338–43. doi: 10.1159/000118379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yepes M, Roussel BD, Ali C, Vivien D. Tissue-type plasminogen activator in the ischemic brain: more than a thrombolytic. Trends Neurosci. 2009 Jan;32(1):48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polavarapu R, Gongora MC, Yi H, Ranganthan S, Lawrence DA, Strickland D, et al. Tissue-type plasminogen activator-mediated shedding of astrocytic low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein increases the permeability of the neurovascular unit. Blood. 2007 Apr 15;109(8):3270–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-043125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Su EJ, Fredriksson L, Geyer M, Folestad E, Cale J, Andrae J, et al. Activation of PDGF-CC by tissue plasminogen activator impairs blood-brain barrier integrity during ischemic stroke. Nat Med. 2008 Jul;14(7):731–7. doi: 10.1038/nm1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haile WB, Wu J, Echeverry R, Wu F, An J, Yepes M. Tissue-type plasminogen activator has a neuroprotective effect in the ischemic brain mediated by neuronal TNF-alpha. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012 Jan;32(1):57–69. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeanneret V, Yepes M. The Plasminogen Activation System Promotes Dendritic Spine Recovery and Improvement in Neurological Function After an Ischemic Stroke. Transl Stroke Res. 2016 Feb; doi: 10.1007/s12975-016-0454-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bertrand T, Lesept F, Chevilley A, Lenoir S, Aimable M, Briens A, et al. Conformations of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) orchestrate neuronal survival by a crosstalk between EGFR and NMDAR. Cell Death Dis. 2015 Oct 15;6:e1924. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lemarchand E, Maubert E, Haelewyn B, Ali C, Rubio M, Vivien D. Stressed neurons protect themselves by a tissue-type plasminogen activator-mediated EGFR-dependent mechanism. Cell Death Differ. 2016 Jan;23(1):123–31. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lemarchant S, Docagne F, Emery E, Vivien D, Ali C, Rubio M. tPA in the injured central nervous system: different scenarios starring the same actor? Neuropharmacology. 2012 Feb;62(2):749–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee TW, Tsang VW, Birch NP. Physiological and pathological roles of tissue plasminogen activator and its inhibitor neuroserpin in the nervous system. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:396. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fredriksson L, Lawrence DA, Medcalf RL. tPA Modulation of the Blood–Brain Barrier: A Unifying Explanation for the Pleiotropic Effects of tPA in the CNS. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2017;43(02):154–68. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1586229. // 02.03.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grummisch JA, Jadavji NM, Smith PD. The pleiotropic effects of tissue plasminogen activator in the brain: implications for stroke recovery. Neural Regeneration Research. 2016;11(9):1401–02. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.191204. 09/01/accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heeremans JL, Gerritsen HR, Meusen SP, Mijnheer FW, Gangaram Panday RS, Prevost R, et al. The preparation of tissue-type Plasminogen Activator (t-PA) containing liposomes: entrapment efficiency and ultracentrifugation damage. J Drug Target. 1995;3(4):301–10. doi: 10.3109/10611869509015959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heeremans JL, Prevost R, Bekkers ME, Los P, Emeis JJ, Kluft C, et al. Thrombolytic treatment with tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA) containing liposomes in rabbits: a comparison with free t-PA. Thromb Haemost. 1995 Mar;73(3):488–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lanza GM, Marsh JN, Hu G, Scott MJ, Schmieder AH, Caruthers SD, et al. Rationale for a nanomedicine approach to thrombolytic therapy. Stroke. 2010 Oct;41(10 Suppl):S42–4. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.598656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soeda S, Kakiki M, Shimeno H, Nagamatsu A. Some properties of tissue-type plasminogen activator reconstituted onto phospholipid and/or glycolipid vesicles. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987 Jul;146(1):94–100. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90695-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27•.Koudelka S, Mikulik R, Mašek J, Raška M, Turanek Knotigova P, Miller AD, et al. Liposomal nanocarriers for plasminogen activators. J Control Release. 2016 Apr;227:45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.02.019. Detailed description of the preparation, physico-chemical characterization, and thrombolytic efficacy of liposomal plasminogen activators such as streptokinase, tissue-plasminogen activator and urokinase. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim JY, Kim JK, Park JS, Byun Y, Kim CK. The use of PEGylated liposomes to prolong circulation lifetimes of tissue plasminogen activator. Biomaterials. 2009 Oct;30(29):5751–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asahi M, Rammohan R, Sumii T, Wang X, Pauw RJ, Weissig V, et al. Antiactin-targeted immunoliposomes ameliorate tissue plasminogen activator-induced hemorrhage after focal embolic stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003 Aug;23(8):895–9. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000072570.46552.DF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ware S, Donahue JP, Hawiger J, Anderson WF. Structure of the fibrinogen gamma-chain integrin binding and factor XIIIa cross-linking sites obtained through carrier protein driven crystallization. Protein Sci. 1999 Dec;8(12):2663–71. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.12.2663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Absar S, Nahar K, Kwon YM, Ahsan F. Thrombus-targeted nanocarrier attenuates bleeding complications associated with conventional thrombolytic therapy. Pharm Res. 2013 Jun;30(6):1663–76. doi: 10.1007/s11095-013-1011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang SS, Chou NK, Chung TW. The t-PA-encapsulated PLGA nanoparticles shelled with CS or CS-GRGD alter both permeation through and dissolving patterns of blood clots compared with t-PA solution: an in vitro thrombolysis study. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009 Dec;91(3):753–61. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chung TW, Wang SS, Tsai WJ. Accelerating thrombolysis with chitosan-coated plasminogen activators encapsulated in poly-(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2008 Jan;29(2):228–37. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park Y, Liang J, Yang Z, Yang VC. Controlled release of clot-dissolving tissue-type plasminogen activator from a poly(L-glutamic acid) semi-interpenetrating polymer network hydrogel. J Control Release. 2001 Jul;75(1–2):37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00360-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35••.Korin N, Kanapathipillai M, Matthews BD, Crescente M, Brill A, Mammoto T, et al. Shear-activated nanotherapeutics for drug targeting to obstructed blood vessels. Science. 2012 Aug;337(6095):738–42. doi: 10.1126/science.1217815. This study offered a novel biophysical strategy for targeted thrombolysis, which uses high shear stress caused by vascular narrowing as a targeting mechanism to deliver drugs to obstructed blood vessels. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uesugi Y, Kawata H, Jo J, Saito Y, Tabata Y. An ultrasound-responsive nano delivery system of tissue-type plasminogen activator for thrombolytic therapy. J Control Release. 2010 Oct;147(2):269–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.07.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uesugi Y, Kawata H, Saito Y, Tabata Y. Ultrasound-responsive thrombus treatment with zinc-stabilized gelatin nano-complexes of tissue-type plasminogen activator. J Drug Target. 2012 Apr;20(3):224–34. doi: 10.3109/1061186X.2011.633259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tran PH, Tran TT, Vo TV, Lee BJ. Promising iron oxide-based magnetic nanoparticles in biomedical engineering. Arch Pharm Res. 2012 Dec;35(12):2045–61. doi: 10.1007/s12272-012-1203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castellanos-Rubio I, Insausti M, de Muro I, Arias-Duque D, Hernandez-Garrido J, Rojo T, et al. The impact of the chemical synthesis on the magnetic properties of intermetallic PdFe nanoparticles. Journal of Nanoparticle Research. 2015 May 22;17(5) 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 40•.Wu W, Wu Z, Yu T, Jiang C, Kim WS. Recent progress on magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: synthesis, surface functional strategies and biomedical applications. Sci Technol Adv Mater. 2015 Apr;16(2):023501. doi: 10.1088/1468-6996/16/2/023501. An exhaustive review about the synthesis, surface functional strategies and biomedical applications of magnetic nanoparticles. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma YH, Wu SY, Wu T, Chang YJ, Hua MY, Chen JP. Magnetically targeted thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator bound to polyacrylic acid-coated nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2009 Jul;30(19):3343–51. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen JP, Yang PC, Ma YH, Lu YJ. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for delivery of tissue plasminogen activator. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2011 Dec;11(12):11089–94. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2011.3953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen JP, Yang PC, Ma YH, Tu SJ, Lu YJ. Targeted delivery of tissue plasminogen activator by binding to silica-coated magnetic nanoparticle. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:5137–49. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S36197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang HW, Hua MY, Lin KJ, Wey SP, Tsai RY, Wu SY, et al. Bioconjugation of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator to magnetic nanocarriers for targeted thrombolysis. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:5159–73. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S32939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen J-P, Yang P-C, Ma Y-H, Wu T. Characterization of chitosan magnetic nanoparticles for in situ delivery of tissue plasminogen activator. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2011;84(1):364–72. 2/11/ [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kempe M, Kempe H, Snowball I, Wallen R, Arza CR, Gotberg M, et al. The use of magnetite nanoparticles for implant-assisted magnetic drug targeting in thrombolytic therapy. Biomaterials. 2010 Dec;31(36):9499–510. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47••.Silva AKA, Luciani N, Gazeau F, Aubertin K, Bonneau S, Chauvierre C, et al. Combining magnetic nanoparticles with cell derived microvesicles for drug loading and targeting. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine. 2015;11(3):645–55. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2014.11.009. 4//; This study developed a hybrid vector using macrophages to produce microvesicles containing both iron oxide and chemotherapeutic agents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48•.Tadayon A, Jamshidi R, Esmaeili A. Targeted thrombolysis of tissue plasminogen activator and streptokinase with extracellular biosynthesis nanoparticles using optimized Streptococcus equi supernatant. Int J Pharm. 2016 Mar 30;501(1–2):300–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.02.011. This study employed extracellular biosynthesized magnetic nanoparticles to deliver both tissue plasminogen activator and streptokinase. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49••.Voros E, Cho M, Ramirez M, Palange AL, De Rosa E, Key J, et al. TPA Immobilization on Iron Oxide Nanocubes and Localized Magnetic Hyperthermia Accelerate Blood Clot Lysis. Advanced Functional Materials. 2015;25(11):1709–18. This study proved that tPA-loaded magnetic nanoparticles can destroy blood clots 100 to 1,000 times faster than a commonly used clot-busting technique. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu J, Huang W, Huang S, ZhuGe Q, Jin K, Zhao Y. Magnetically active Fe3O4 nanorods loaded with tissue plasminogen activator for enhanced thrombolysis. Nano Research. 2016;9(9):2652–61. 2016/09/01. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meairs S. Sonothrombolysis. Front Neurol Neurosci. 2015;36:83–93. doi: 10.1159/000366239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Francis CW, Blinc A, Lee S, Cox C. Ultrasound accelerates transport of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator into clots. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1995;21(3):419–24. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(94)00119-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Siddiqi F, Blinc A, Braaten J, Francis CW. Ultrasound increases flow through fibrin gels. Thromb Haemost. 1995 Mar;73(3):495–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.M.D. CWF. Ultrasound-Enhanced Thrombolysis. Echocardiography. 2001;18(3):239–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8175.2001.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55•.de Saint Victor M, Crake C, Coussios CC, Stride E. Properties, characteristics and applications of microbubbles for sonothrombolysis. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2014 Feb;11(2):187–209. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2014.868434. A detailed review on microbubbles for sonothrombolysis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alexandrov AV, Demchuk AM, Felberg RA, Christou I, Barber PA, Burgin WS, et al. High rate of complete recanalization and dramatic clinical recovery during tPA infusion when continuously monitored with 2-MHz transcranial doppler monitoring. Stroke. 2000 Mar;31(3):610–4. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.3.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alexandrov AV, Molina CA, Grotta JC, Garami Z, Ford SR, Alvarez-Sabin J, et al. Ultrasound-enhanced systemic thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2004 Nov;351(21):2170–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eggers J, Koch B, Meyer K, Konig I, Seidel G. Effect of ultrasound on thrombolysis of middle cerebral artery occlusion. Ann Neurol. 2003 Jun;53(6):797–800. doi: 10.1002/ana.10590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Daffertshofer M, Gass A, Ringleb P, Sitzer M, Sliwka U, Els T, et al. Transcranial low-frequency ultrasound-mediated thrombolysis in brain ischemia: increased risk of hemorrhage with combined ultrasound and tissue plasminogen activator: results of a phase II clinical trial. Stroke. 2005 Jul;36(7):1441–6. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000170707.86793.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.El-Sherbiny IM, Elkholi IE, Yacoub MH. Tissue plasminogen activator-based clot busting: Controlled delivery approaches. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2014;2014(3):336–49. doi: 10.5339/gcsp.2014.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Molina CA, Ribo M, Rubiera M, Montaner J, Santamarina E, Delgado-Mederos R, et al. Microbubble administration accelerates clot lysis during continuous 2-MHz ultrasound monitoring in stroke patients treated with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator. Stroke. 2006 Feb;37(2):425–9. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000199064.94588.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Everbach EC, Francis CW. Cavitational mechanisms in ultrasound-accelerated thrombolysis at 1 MHz. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2000 Sep;26(7):1153–60. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(00)00250-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dijkmans PA, Juffermans LJ, Musters RJ, van Wamel A, ten Cate FJ, van Gilst W, et al. Microbubbles and ultrasound: from diagnosis to therapy. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2004 Aug;5(4):245–56. doi: 10.1016/j.euje.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Unger EC, Porter T, Culp W, Labell R, Matsunaga T, Zutshi R. Therapeutic applications of lipid-coated microbubbles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2004 May;56(9):1291–314. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hua X, Liu P, Gao Y-H, Tan K-B, Zhou L-N, Liu Z, et al. Construction of thrombus-targeted microbubbles carrying tissue plasminogen activator and their in vitro thrombolysis efficacy: a primary research. Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis. 2010;30(1):29–35. doi: 10.1007/s11239-010-0450-z. 2010/07/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hua X, Zhou L, Liu P, He Y, Tan K, Chen Q, et al. In vivo thrombolysis with targeted microbubbles loading tissue plasminogen activator in a rabbit femoral artery thrombus model. Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis. 2014;38(1):57–64. doi: 10.1007/s11239-014-1071-8. 2014/07/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yan W-C, Ong XJ, Pun KT, Tan DY, Sharma VK, Tong YW, et al. Preparation of tPA-loaded microbubbles as potential theranostic agents: A novel one-step method via coaxial electrohydrodynamic atomization technique. Chemical Engineering Journal. 2017;307:168–80. 2017/01/01/ [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yan W-C, Chua QW, Ong XJ, Sharma VK, Tong YW, Wang C-H. Fabrication of ultrasound-responsive microbubbles via coaxial electrohydrodynamic atomization for triggered release of tPA. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 2017;501:282–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2017.04.073. 2017/09/01/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smith DA, Vaidya SS, Kopechek JA, Huang SL, Klegerman ME, McPherson DD, et al. Ultrasound-triggered release of recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator from echogenic liposomes. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2010 Jan;36(1):145–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang SL. Liposomes in ultrasonic drug and gene delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008 Jun;60(10):1167–76. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tiukinhoy-Laing SD, Huang S, Klegerman M, Holland CK, McPherson DD. Ultrasound-facilitated thrombolysis using tissue-plasminogen activator-loaded echogenic liposomes. Thromb Res. 2007;119(6):777–84. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smith DAB, Vaidya S, Kopechek JAEK, Huang SL, McPherson DD. Echogenic liposomes loaded with recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (rt-PA) for image-guided, ultrasound-triggered drug release. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2008;122(5) [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shekhar H, Bader KB, Huang S, Peng T, McPherson DD, Holland CK. In vitro thrombolytic efficacy of echogenic liposomes loaded with tissue plasminogen activator and octafluoropropane gas. Phys Med Biol. 2016 Dec;62(2):517–38. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/62/2/517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hagisawa K, Nishioka T, Suzuki R, Maruyama K, Takase B, Ishihara M, et al. Thrombus-targeted perfluorocarbon-containing liposomal bubbles for enhancement of ultrasonic thrombolysis: in vitro and in vivo study. J Thromb Haemost. 2013 Aug;11(8):1565–73. doi: 10.1111/jth.12321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shaw GJ, Meunier JM, Huang SL, Lindsell CJ, McPherson DD, Holland CK. Ultrasound-enhanced thrombolysis with tPA-loaded echogenic liposomes. Thromb Res. 2009 Jul;124(3):306–10. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tiukinhoy-Laing SD, Buchanan K, Parikh D, Huang S, MacDonald RC, McPherson DD, et al. Fibrin targeting of tissue plasminogen activator-loaded echogenic liposomes. J Drug Target. 2007 Feb;15(2):109–14. doi: 10.1080/10611860601140673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Klegerman ME, Zou Y, McPherson DD. Fibrin targeting of echogenic liposomes with inactivated tissue plasminogen activator. J Liposome Res. 2008;18(2):95–112. doi: 10.1080/08982100802118482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Laing ST, Moody MR, Kim H, Smulevitz B, Huang S-L, Holland CK, et al. Thrombolytic efficacy of tissue plasminogen activator-loaded echogenic liposomes in a rabbit thrombus model. Thrombosis Research. 2012;130(4):629–35. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.11.010. 10// [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79••.Kandadai MA, Mukherjee P, Shekhar H, Shaw GJ, Papautsky I, Holland CK. Microfluidic manufacture of rt-PA-loaded echogenic liposomes. Biomed Microdevices. 2016 Jun;18(3):48. doi: 10.1007/s10544-016-0072-0. This study utilized microfluidic flow-focusing device to generate monodisperse rtPA-loaded echogenic liposomes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80••.Absar S, Choi S, Yang VC, Kwon YM. Heparin-triggered release of camouflaged tissue plasminogen activator for targeted thrombolysis. J Control Release. 2012 Jan;157(1):46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.09.060. This study is the first report of camouflaged-tPA electrostatic supramolecular complexes. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Absar S, Choi S, Ahsan F, Cobos E, Yang VC, Kwon YM. Preparation and characterization of anionic oligopeptide-modified tissue plasminogen activator for triggered delivery: an approach for localized thrombolysis. Thromb Res. 2013 Mar;131(3):e91–9. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Absar S, Kwon YM, Ahsan F. Bio-responsive delivery of tissue plasminogen activator for localized thrombolysis. J Control Release. 2014 Mar;177:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bahadar H, Maqbool F, Niaz K, Abdollahi M. Toxicity of Nanoparticles and an Overview of Current Experimental Models. Iran Biomed J. 2016;20(1):1–11. doi: 10.7508/ibj.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Moskowitz MA, Lo EH, Iadecola C. The Science of Stroke: Mechanisms in Search of Treatments. Neuron. 68(1):161. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sicard KM, Fisher M. Animal models of focal brain ischemia. Exp Transl Stroke Med. 2009 Nov 13;1:7. doi: 10.1186/2040-7378-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liang LJ, Yang JM, Jin XC. Cocktail treatment, a promising strategy to treat acute cerebral ischemic stroke? Med Gas Res. 2016 Mar;6(1):33–38. doi: 10.4103/2045-9912.179343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Murata Y, Rosell A, Scannevin RH, Rhodes KJ, Wang X, Lo EH. Extension of the thrombolytic time window with minocycline in experimental stroke. Stroke. 2008 Dec;39(12):3372–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.514026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Li M, Zhang Z, Sun W, Koehler RC, Huang J. 17β-estradiol attenuates breakdown of blood-brain barrier and hemorrhagic transformation induced by tissue plasminogen activator in cerebral ischemia. Neurobiol Dis. 2011 Dec;44(3):277–83. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fukuta T, Asai T, Yanagida Y, Namba M, Koide H, Shimizu K, et al. Combination therapy with liposomal neuroprotectants and tissue plasminogen activator for treatment of ischemic stroke. The FASEB Journal. 2017;31(5):1879–90. doi: 10.1096/fj.201601209R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90••.Lee HJ, Park J, Yoon OJ, Kim HW, Lee DY, Kim DH, et al. Amine-modified single-walled carbon nanotubes protect neurons from injury in a rat stroke model. Nat Nano. 2011;6(2):121–25. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.281. 02//print. This study proved that pre-treating rats with single-walled carbon nanotubes can protect neurons in the brain and enhance the recovery of motor functions after injury. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Higgins P, Dawson J, Walters M. Nat Nanotechnol. England: 2011. Nanomedicine: Nanotubes reduce stroke damage; pp. 83–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rabinstein AA. Stroke in 2015: Acute endovascular recanalization therapy comes of age. NATURE REVIEWS NEUROLOGY. 2016;12:67–68. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]