Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Escalating health care spending is a concern in Western countries, given the lack of evidence of a direct connection between spending and improvements in health. We aimed to determine the association between spending on health care and social programs and health outcomes in Canada.

METHODS:

We used retrospective data from Canadian provincial expenditure reports, for the period 1981 to 2011, to model the effects of social and health spending (as a ratio, social/health) on potentially avoidable mortality, infant mortality and life expectancy. We used linear regressions, accounting for provincial fixed effects and time, and controlling for confounding variables at the provincial level.

RESULTS:

A 1-cent increase in social spending per dollar spent on health was associated with a 0.1% (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.04% to 0.16%) decrease in potentially avoidable mortality and a 0.01% (95% CI 0.01% to 0.02%) increase in life expectancy. The ratio had a statistically nonsignificant relationship with infant mortality (p = 0.2).

INTERPRETATION:

Population-level health outcomes could benefit from a reallocation of government dollars from health to social spending, even if total government spending were left unchanged. This result is consistent with other findings from Canada and the United States.

The need to lower health care costs is recognized by public and private payers in most developed countries, including Canada.1 As noted in a recent report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Healthcare costs are rising so fast in advanced economies that they will become unaffordable by mid-century without reforms.”2

International data suggest that an exclusive focus on health care expenditures in the discussion about health care reform has been misleading;3,4 using spending and health data from 30 industrialized countries, these authors found that the total amount spent on both health and social programs explained health outcomes. Broader international comparisons have supported that finding.5 A follow-up study using state-level data from the United States further established social expenditures as a source of population health gains with a more culturally homogeneous data set.6 A 2009 Canadian Senate report suggested that the health care system accounted for only 25% of health outcomes, noting, “The socioeconomic environment is the most powerful of the determinants of health.”7

Conceptually, addressing the social determinants of health can be conceived as the equivalent of treating the root causes of disease and ill health.8 As a result, spending on social services, widely defined, is a good proxy for public spending on the social determinants of health. However, this type of spending is difficult to quantify; individual government departments can have several functions, and although some clearly pertain to social services, categorization is more difficult when the social impact is indirect or only part of a department’s function.

Building on a long tradition of comparative public policy in Canada,9–11 we conducted a comparative analysis of health and social spending in Canadian provinces, to examine whether ratios of social to health spending in these jurisdictions were correlated with health.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a retrospective longitudinal study of 9 Canadian provinces from 1981 to 2011 (279 province-year observations). Prince Edward Island (2016 population of 148 600, less than 0.5% of Canada’s total population) and the northern territories (combined population 119 100) were not included because of insufficient data. We used publicly available time-series data.12 These data, drawn from provincial public accounts, report health and social spending by function across government accounts, considering the changing names of government departments or portfolios when aggregating measures. Definitions of health and social spending are presented in Appendix 1 (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170132/-/DC1).

Dependent variables

The dependent variables were 3 measures of province-level health outcomes: potentially avoidable mortality (age standardized per 100 000 population), infant mortality (per 1000 live births) and life expectancy at birth (yr). These variables are indicators of the performance of the health care system and of population health.13 Rates of mortality from avoidable causes have many determinants, including access to treatment, health behaviours, environmental conditions and technical change in medical treatment. All nonspending variables were retrieved from Statistics Canada’s publicly available Canadian Socioeconomic Information Management system (known as CANSIM). We excluded education spending from our definition of social spending. Accurately capturing the influence of education spending on our outcomes of interest would have necessitated assigning education spending to the cohorts who benefit from it; education spending almost entirely benefits school-age children at the time it is spent, but outcomes may occur later in life. Health and social spending, on the other hand, can have contemporaneous benefits: an increase in physician salaries or welfare payments is experienced immediately.

Independent variables

The independent variable of interest for each province and year was the ratio of provincial government spending on social services relative to spending on health care.3,5,6 Demographic controls included the percentages of each province’s population who were 65 years or older, who were female and who were living in rural areas, as well as the total population size. Economic controls included the unemployment rate, the median after-tax income (natural log), the Gini coefficient (a validated measure that is widely used to describe regional income inequality, with values between 0 and 1, where 0 = perfect equality and 1 = perfect inequality) for after-tax income and total real provincial expenditure (in billions of dollars).

Statistical analysis

We fitted linear regression models for each health outcome as a function of the ratio of social to health spending and the independent variables to control for confounding influences on the dependent variables. We numbered the models as follows: model 1 for potentially avoidable mortality, model 2 for infant mortality and model 3 for life expectancy. We present unadjusted and adjusted models. We also report standardized regression coefficients for the adjusted models. Our regressions included provincial fixed effects and dummy variables indicating year. Fixed-effects regression is a technique commonly used with panel data to control for idiosyncratic effects that cannot be observed in the data.14 In our case, provincial fixed effects controlled for time-invariant provincial factors, such as weather or political trends. For all statistical analyses, we used Stata, version 14 (StataCorp LLC).

Ethics approval

The study institution (University of Calgary) does not require ethics approval for projects using publicly available secondary data, such as this one.

Results

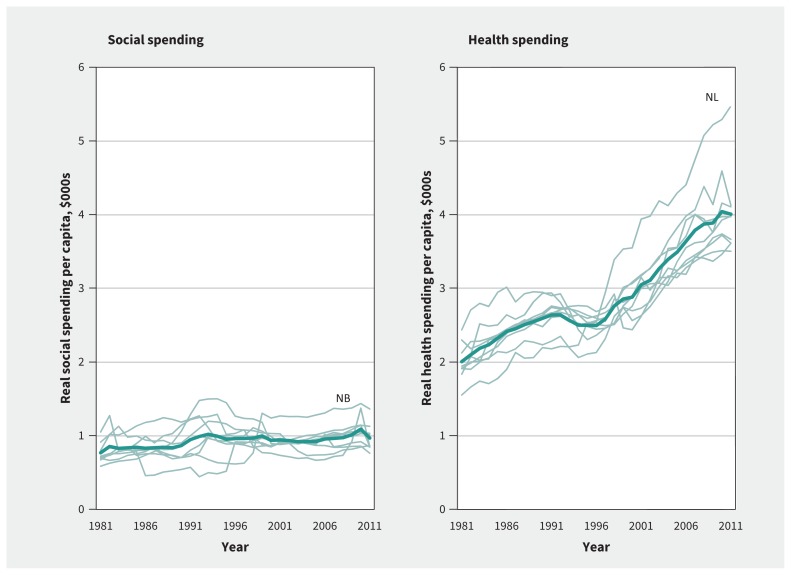

Summary statistics describing the distribution of spending and health outcomes averaged across the 9 provinces and 31 years are presented in Table 1. Average per capita spending on social services, in thousands of dollars, was 0.93 (standard deviation [SD] 0.19, range 0.44–1.53), whereas average per capita spending on health, in thousands of dollars, was 2.90 (SD 0.71, range 1.55–5.42), about 3 times more. Figure 1 shows these variables over time, with the Canadian average for social spending increasing from about 0.77 thousand to 0.97 thousand per capita and health spending increasing from about 2 thousand to 4 thousand per capita.

Table 1:

Distribution of spending and health outcome variables across the provinces, 1981–2011

| Variable | Mean value ± SD (range) |

|---|---|

| Real social spending per capita, $000s* | 0.93 ± 0.19 (0.44–1.53) |

| Real health spending per capita, $000s* | 2.90 ± 0.71 (1.55–5.42) |

| Potentially avoidable mortality, per 100 000 | 309.59 ± 63.53 (192.8–466.4) |

| Infant mortality, per 1000 live births | 6.57 ± 1.87 (3.2–11.9) |

| Life expectancy, yr† | 79.01 ± 1.10 (76.8–81.7) |

Note: SD = standard deviation.

Base year: 2011.

Life expectancy was modelled from 1990 to 2011 because of limitations on data availability at the provincial level.

Figure 1:

Real spending per capita (thousands of dollars), by province (outliers noted). Light green lines = individual provinces, dark green line = national average. Note: NB = New Brunswick, NL = Newfoundland and Labrador.

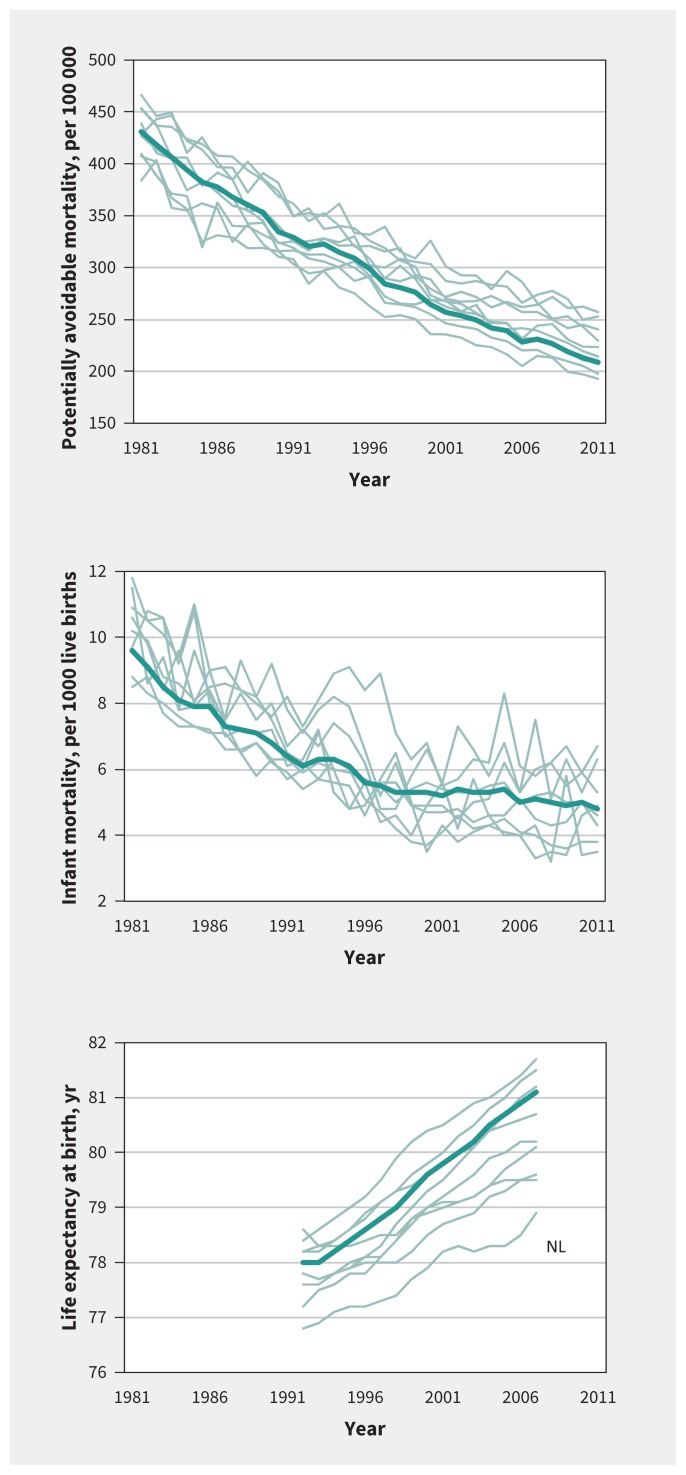

Potentially avoidable mortality, infant mortality and life expectancy are also summarized in Table 1. Since 1981, trends in these variables have shown improvement in every province (Figure 2). The Canadian average for all health outcomes improved as follows: potentially avoidable mortality, from 431 per 100 000 to 208.7 per 100 000; infant mortality, from 9.6 per 100 live births to 4.8 per 100 live births; and life expectancy, from 78 years to 81.1 years.

Figure 2:

Trends over time, at national and provincial levels, of 3 population health variables: potentially avoidable mortality, infant mortality and life expectancy at birth. One outlier is noted. Light green lines = individual provinces, dark green line = national average. Note: NL = Newfoundland and Labrador.

The health variables trended in a positive direction overall, and spending rose over time. Therefore, controlling for the time trend (by adding time fixed effects) was necessary to avoid incorrectly associating spending with improvements in health outcomes because of their common trends. Table 2 shows the key finding of this analysis, that social spending was associated with health outcomes across provinces. A 1-cent increase in social spending per dollar spent on health was associated with a 0.1% (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.04% to 0.16%) decrease in potentially avoidable mortality and a 0.01% (95% CI 0.01% to 0.02%) increase in life expectancy; the result for infant mortality was non-significant. The standardized version of the models allowed us to interpret the coefficients as changes in SDs rather than units. The standardized coefficients in Table 2 show that a 1-SD increase in the ratio of social to health spending was associated with a 0.0462-SD decrease in potentially avoidable mortality and a 0.0819-SD increase in life expectancy. These estimates mean that life expectancy might be expected to have a larger relative change than potentially avoidable mortality with changes in social spending, because of the smaller variance of life expectancy (Figure 2).

Table 2:

Relation between ratio of social to health spending and health outcomes, according to linear regression with province and year as fixed effects*

| Variable | Model 1: potentially avoidable mortality (natural log) | Model 2: infant mortality (natural log) | Model 3: life expectancy† (natural log) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted† | Standardized | Unadjusted | Adjusted† | Standardized | Unadjusted | Adjusted† | Standardized | |

| Ratio of social to health spending, real $ | −0.0006 (−0.0015 to 0.0002) | −0.0010 (−0.0016 to −0.0004) | −0.0462 (−0.0725 to −0.0200) | −0.0001 (−0.0022 to 0.0020) | −0.0015 (−0.0035 to 0.0006) | −0.0479 (−0.1147 to 0.0190) | < 0.0001 (−0.0001 to 0.0001) | 0.0001 (0.0001 to 0.0002) | 0.0819 (0.0487 to 0.1151) |

|

| |||||||||

| Age > 65 yr, % | −3.8955 (−4.8257 to −2.9654) | −4.0497 (−5.0067 to −3.0928) | −0.3867 (−0.4781 to −0.2953) | −3.3791 (−6.0625 to −0.6957) | 0.5204 (−2.8888 to 3.9295) | 0.0356 (−0.1974 to 0.2685) | 0.1779 (0.0279 to 0.3279) | 0.2949 (0.1570 to 0.4328) | 0.4141 (0.2205 to 0.6078) |

|

| |||||||||

| Sex, female, % | −0.2513 (−3.4878 to 2.9852) | 1.6299 (−1.3909 to 4.6507) | 0.0366 (−0.0312 to 0.1043) | −17.5552 (−25.5930 to −9.5175) | −18.3461 (−29.1077 to −7.5844) | −0.2945 (−0.4673 to −0.1218) | −0.4898 (−0.8639 to −0.1156) | −0.9719 (−1.3623 to −0.5816) | −0.3207 (−0.4494 to −0.1919) |

|

| |||||||||

| Rural residence, % | 0.0069 (0.0010 to 0.0129) | −0.0024 (−0.0073 to 0.0024) | −0.1480 (−0.4436 to 0.1475) | 0.0198 (0.0046 to 0.0351) | 0.0161 (−0.0013 to 0.0335) | 0.6988 (−0.0547 to 1.4524) | −0.0026 (−0.0037 to −0.0016) | −0.0012 (−0.0020 to −0.0003) | −1.0328 (−1.8096 to −0.2561) |

|

| |||||||||

| Unemployment rate, percentage points | 0.0035 (−0.0029 to 0.0099) | 0.0067 (0.0016 to 0.0118) | 0.1222 (0.0287 to 0.2157) | 0.0173 (0.0009 to 0.0338) | 0.0200 (0.0018 to 0.0383) | 0.2612 (0.0229 to 0.4996) | −0.0005 (−0.0015 to 0.0006) | −0.0007 (−0.0014 to 0.0001) | −0.1775 (−0.3697 to 0.0148) |

|

| |||||||||

| Median after-tax income, natural log | 0.4578 (0.2952 to 0.6204) | 0.2939 (0.1433 to 0.4446) | 0.1670 (0.0814 to 0.2526) | 0.6687 (0.2316 to 1.1058) | 0.3758 (−0.1609 to 0.9126) | 0.1528 (−0.0654 to 0.3710) | −0.0157 (−0.0376 to 0.0062) | −0.0546 (−0.0728 to −0.0363) | −0.4559 (−0.6083 to −0.3035) |

|

| |||||||||

| Gini coefficient of after-tax income | −1.2888 (−2.0201 to −0.5575) | −0.0132 (−0.6228 to 0.5964) | −0.0010 (−0.0471 to 0.0451) | −0.8898 (−2.8185 to 1.0389) | −1.1496 (−3.3214 to 1.0222) | −0.0622 (−0.1798 to 0.0553) | 0.0298 (−0.0509 to 0.1105) | 0.0080 (−0.0433 to 0.0592) | 0.0089 (−0.0482 to 0.0659) |

|

| |||||||||

| Real total government expenditure, $ billions | −0.0026 (−0.0035 to −0.0016) | 0.0032 (0.0010 to 0.0054) | 0.4369 (0.1323 to 0.7416) | 0.0031 (0.0005 to 0.0057) | 0.0053 (−0.0026 to 0.0131) | 0.5230 (−0.2536 to 1.2996) | 0.0003 (0.0001 to 0.0004) | −0.0004 (−0.0007 to −0.0002) | −0.8694 (−1.3362 to −0.4025) |

|

| |||||||||

| Population, millions | −0.0455 (−0.0582 to −0.0328) | −0.0966 (−0.1301 to −0.0631) | −1.6427 (−2.2126 to −1.0728) | 0.0326 (−0.0031 to 0.0684) | −0.0476 (−0.1670 to 0.0718) | −0.5789 (−2.0319 to 0.8741) | 0.0072 (0.0050 to 0.0094) | 0.0130 (0.0092 to 0.0169) | 3.2534 (2.2923 to 4.2145) |

|

| |||||||||

| Constant | NA | 2.7585 (0.3730 to 5.1440) | 1.1267 (0.9716 to 1.2817) | NA | 7.1510 (−1.3474 to to 15.6495) | 1.5481 (1.1527 to 1.9434) | NA | 5.4249 (5.0738 to 5.7761) | 1.0274 (0.7688 to 1.2860) |

|

| |||||||||

| No. of observations | 279 | NA | NA | 279 | NA | NA | 144 | NA | NA |

Note: NA = not applicable.

Fixed effects for province and year were included in each model (coefficients not reported). For each value, the 95% confidence interval is shown in parentheses.

Interpretation of the adjusted model coefficients requires multiplying the coefficient by 100, then interpreting the resultant number as a percent change in the outcome per 1-unit change in the independent variable. For example, in model 1, a 1-cent increase in social spending for each dollar in health spending was associated with a 0.1% decrease in potentially avoidable mortality.

Our adjusted model results can be calibrated with government spending data. Using 2011 values for Ontario (the most populous province), a 1-cent increase in social spending for each dollar of health spending would represent an additional $350 million on social spending (an increase of 2.6% in the 2011 level of funding) combined with a decrease of $350 million on health spending (a decrease of 0.8% in the 2011 level of funding). On the basis of the model results, potentially avoidable mortality is predicted to decrease from 197.8 to 197.6 per 100 000 in 2011, which is an additional 3% decrease from the 2010 value of 205.3 per 100 000. Similarly, life expectancy would increase by 0.01% in 2007 (from 81.50 to 81.51 yr), which is an additional increase of 5% from the 2006 level of 81.3 years.

Several of the coefficients in Table 2 indicate that the covariables were associated with the population health variables: the unemployment rate was associated with worse potentially avoidable mortality and infant mortality outcomes; larger populations were associated with better potentially avoidable mortality and infant mortality outcomes; a larger rural population was associated with worse outcomes for potentially avoidable mortality; and higher median income and higher real government expenditures were associated with worse outcomes for potentially avoidable mortality and life expectancy. For example, an increase in the unemployment rate of 1 percentage point is associated with a 0.67% (95% CI 0.16% to 1.18%) increase in potentially avoidable mortality and a 2.0% (95% CI 0.18% to 3.83%) increase in infant mortality.

Appendices 2 and 3 (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170132/-/DC1) are sensitivity analyses of the main result from Table 2. Appendix 2 shows that social spending was associated with favourable trends in potentially avoidable mortality and life expectancy if we decompose the ratio as follows: a 1% increase in social spending is associated with a decrease of 0.034% (95% CI –0.057% to –0.011%) in potentially avoidable mortality and an increase of 0.006% (95% CI 0.004% to 0.008%) in life expectancy, whereas a 1% increase in health spending is associated with an increase of 0.064% (95% CI 0.002% to 0.126%) in potentially avoidable mortality and no change in life expectancy. Appendix 3 shows that using the ratio from 1 or 2 years before the outcome produced estimates similar to those obtained with contemporaneous values, which indicates that the result in Table 2 is not explained by reverse causality.

Interpretation

Our analysis showed that increased social spending was positively associated with population health measures in Canada at the provincial level. Our supplementary analyses showed that health spending did not have the same association. In all of these analyses, we controlled for the effects of province-level variables and time.

The ratio of social to health spending is a potential avenue through which the government can affect population health outcomes. The ratio of social to health spending is low, so redistributing money from health to social spending represents a small relative change in health spending. The literature suggests that additional spending on health does not necessarily affect population health outcomes,15 yet in all provinces, health spending increased rapidly after a drop in the mid-1990s, while social spending remained relatively flat. If a proportionately small funding reallocation from health to social spending is associated with small improvements in population health outcomes, then the improvements in health variables that we observed in our data could have been larger with no change to the government’s overall spending.

Our sensitivity analysis (Appendix 2) showed that social spending is associated with improvements in the population health variables, evidence of the notion that further spending on health may not improve population health outcomes as effectively as social spending. If social spending addresses the social determinants of health, then it is a form of preventive health spending and changes the risk distribution for the entire population8 rather than treating those who present with disease. Redirecting resources from health to social services, at the margin, is an efficient way to improve health outcomes.

This information can help decision-makers in deciding where to spend marginal dollars to improve population health, especially in the face of competing claims from multiple stakeholders. For example, a provincial medical association may be negotiating a service agreement with the provincial government that includes, among other things, a payment schedule. The following might be a typical interaction: The province offers a payment schedule that includes clawbacks for top-billing physicians to control costs; the physicians caution that these clawbacks may harm health outcomes for patients. In this discussion, the focus is on health outcomes as a function of health spending, rather than a shared understanding that spending on social services may also improve health outcomes.

There is growing evidence of a causal relationship between inequality and poor health.16,17 It is likely that most beneficiaries of increased social spending would be those with the lowest incomes (and consequently shortest life expectancies), and they might see larger-than-average gains within provinces.

Our analysis agrees with previously cited international and US findings3–6 and other Canadian work using different data.18 Multiple studies have indicated that improving population health requires consideration of government spending beyond health care. Because of model and data set differences across studies, direct comparisons are not possible, but broadly, increased social spending (either as welfare generosity, a share of total gross domestic product or a proportion of health spending) is favourably associated with health outcomes such as life expectancy, infant mortality, potential years of life lost, obesity prevalence, acute myocardial infarction and mental health days off work.3–6,18 Our study differs from previous studies in terms of both the length of time observed and the number of control variables utilized, but the relation between social spending and health outcomes holds. Marginal increases in health care spending in Canada have not been shown to directly improve population health,19 and while health spending per capita within Canada continues to grow, the nature of the effects on health outcomes is up for debate.20,21

Allocative decisions internal to the health sector are only part of the discussion on how public spending (including social assistance, education, housing and public pensions) affects health outcomes. Health care spending is important in the treatment of disease, but the determination of population health is the end result of a complicated system that includes the lifelong influence of the social determinants of health on individuals (broadly including income, education, ethnicity, early childhood development, the natural and physical built environments, and inequality22), which are driven by proximal features of the social and physical environment.15

Limitations

Our analysis relied on contemporaneous time-series data, which raises the possibility of reverse causation (e.g., improved health outcomes might have allowed for greater social spending). However, social spending did not increase as substantially over our study period as did health spending (Figure 1); therefore, if health improvements do drive government spending decisions, our data point to health spending getting a larger share of the marginal dollar. Furthermore, introducing lagged social to health spending variables (Appendix 3) showed that our results were robust to single-period and dual-period treatments.

Comparable government data on disaggregated measures of health and social spending do not exist over a sufficiently long period. However, our data span a long period (31 yr), meaning that the time dimension of our data captures the influences of the wide changes in spending shown in Figure 1. Furthermore, our analysis includes only province-level spending, and not that of the federal and municipal levels of government. Although spending on health and social services by the federal government and municipalities is somewhat exogenous to spending in these areas by the provinces, including these levels of jurisdiction in the analysis would provide a more complete understanding.

It is possible that there are important differences within provinces. For example, persistent disparities exist in infant mortality rates between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities.23 Additionally, investigating whether there is a threshold effect of social spending is beyond the scope of this paper. All of these are avenues for future research.

Conclusion

The results of our study suggest that spending on social services can improve health. Social policy changes at the margins, where it is possible to affect population health outcomes by reallocating spending in a way that has no effect on the overall government budget.

Footnotes

See related article at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.171530

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Pierre-Gerlier Forest conceived the study around data compiled by Ronald Kneebone. Daniel Dutton conducted the analysis, and all of the authors interpreted the results. Daniel Dutton and Jennifer Zwicker drafted the manuscript. All of the authors provided necessary revisions and input, gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1.Marchildon GP, Di Matteo L, editors. Bending the cost curve in health care: Canada’s provinces in international perspective. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiscal sustainability of health systems. Paris (France): OECD Publishing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley EH, Elkins BR, Herrin J, et al. Health and social services expenditures: associations with health outcomes. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:826–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley EH, Taylor LA. The American health care paradox: why spending more is getting us less. New York: Public Affairs; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubin J, Taylor J, Krapels J, et al. Are better health outcomes related to social expenditure? A cross-national empirical analysis of social expenditure and population health measures. Cambridge (UK): RAND Europe; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley EH, Canavan M, Rogan E, et al. Variation in health outcomes: the role of spending on social services, public health, and health care, 2000–09. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35:760–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.A healthy, productive Canada: a determinant of health approach. Ottawa: Senate Subcommittee on Population Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rose G, Khaw KT, Marmot M. Rose’s strategy of preventive medicine. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennett C. Comparative policy studies in Canada: What state? What art? In: Dobuszinskis L, Howlett M, Laycock D, editors. Policy studies in Canada: the state of the art. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 1996:299–316. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imbeau LM, Landry R, Milner H, et al. Comparative provincial policy analysis: a research agenda. Can J Polit Sci 2000;33:779–804. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montpetit É. A quantitative analysis of the comparative turn in Canadian political science. In: White LA, Simeon R, Vipond R, et al., editors. The comparative turn in Canadian political science. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kneebone R, Wilkins M. Canadian provincial government budget data, 1980/81 to 2013/14. Can Public Policy 2016;42:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Health indicators 2012. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wooldridge JM. Introductory econometrics: a modern approach. 5th ed Mason (OH): South-Western; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans RG, Stoddart GL. Producing health, consuming health care. Soc Sci Med 1990;31:1347–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marmot M, Allen J, Bell R, et al. Consortium for the European Review of Social Determinants of Health and the Health Divide. WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet 2012;380:1011–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pickett KE, Wilkinson RG. Income inequality and health: a causal review. Soc Sci Med 2015;128:316–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ng E, Muntaner C. Welfare generosity and population health among Canadian provinces: a time-series cross-sectional analysis, 1989–2009. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015;69:970–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Health spending: Do countries get what they pay for when it comes to health care? Ottawa: Conference Board of Canada; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans RG. Political wolves and economic sheep: the sustainability of public health insurance in Canada. Vancouver: University of British Columbia, Centre for Health Services and Policy Research; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crémieux PY, Ouellette P, Pilon C. Health care spending as determinants of health outcomes. Health Econ 1999;8:627–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raphael D. Social determinants of health: Canadian perspectives. 3rd ed Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc.; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smylie J, Fell D, Ohlsson AJoint Working Group on First Nations Indian Inuit. Métis Infant Mortality of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. A review of Aboriginal infant mortality rates in Canada: striking and persistent Aboriginal/non-Aboriginal inequities. Can J Public Health 2010;101:143–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]