Abstract

We previously synthesized new 5-thienyl-substituted 2-aminobenzamide-type HDAC1, 2 inhibitors with the (4-ethyl-2,3-dioxopiperazine-1-carboxamido) methyl group. K-560 (1a) protected against neuronal cell death in a Parkinson’s disease model by up-regulating the expression of XIAP. This finding prompted us to design new K-560-related compounds. We examined the structure activity relationship (SAR) for the neuronal protective effects of newly synthesized and known K-560 derivatives after cerebral ischemia. Among them, K-856 (8), containing the (4-methyl-2,5-dioxopiperazin-1-yl) methyl group, exhibited a promising neuronal survival activity. The SAR study strongly suggested that the attachment of a monocyclic 2,3- or 2,5-diketopiperazine group to the 2-amino-5-aryl (but not 2-nitro-5-aryl) scaffold is necessary for K-560-related compounds to exert a potent neuroprotective effect.

Introduction

With a growing aging population, the number of individuals with neurological disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease (PD), and ischemic stroke, is steadily increasing. It is challenging to design effective polypharmacological central nervous system (CNS) drugs because of the complex pathophysiological mechanisms of neurological disorders.

Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors reportedly ameliorated neuronal damage via pleiotropic effects, including anti-excitotoxicity, oxidative stress reduction, and inflammatory response suppression in in vitro and in vivo cerebral ischemia models1. However, the HDAC inhibitors used in these studies were non-specific, exemplified by valproic acid, trichostatin A (TSA), sodium butyrate, and SAHA (Vorinostat), and, thus, are associated with toxicities such as thrombocytopenia, nausea, fatigue, and QT prolongation2,3. These side effects underscore the need for more refined approaches to target HDAC subfamilies in order to reduce neuronal injuries. However, the type of isozyme inhibition that leads to neuroprotection remains unclear. Therefore, the selective targeting of HDAC isoforms with small molecules represents an attractive topic for the development of treatments for neurological disorders with few side effects.

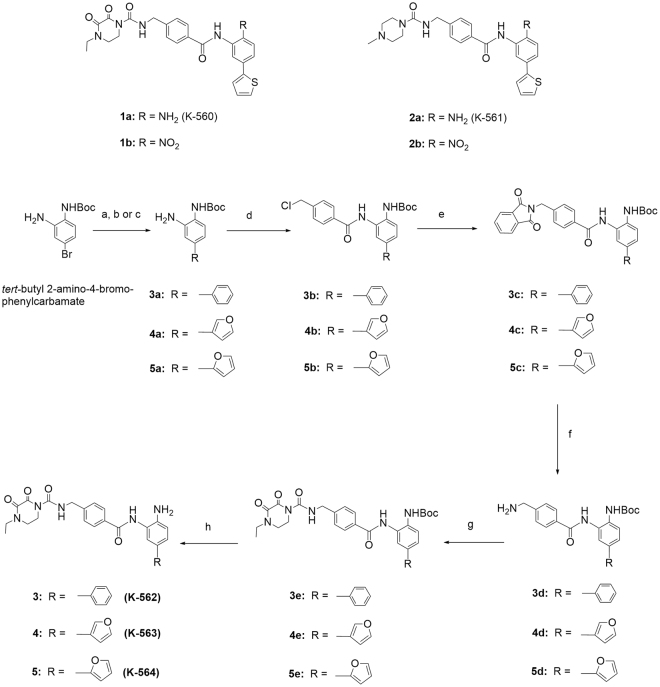

We previously synthesized 5-thienyl-substituted 2-aminobenzamide-type HDAC inhibitors, including K-560 (1a) possessing the (4-ethyl-2,3-dioxopiperazine-1-carboxamido) methyl group and K-561 (2a) having the (4-methylpiperazine-1-carboxamido) methyl group4 (Fig. 1). Compound 1a inhibited HDAC1 and 2 selectively and suppressed the growth of cancer cells, similar to the same type of HDAC inhibitors5–21. However, 1a averted the death of HCT116 human colorectal cancer cells by a mechanism involving activation of the survival signal-related proteins Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)/70-kDa ribosomal protein S6 kinase (p70S6K)22,23. This effect was also applied to neuronal cells, i.e., K-560 (1a) exerted protective effects against 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion/1-methyl-4-phenyl-1, 2, 5, 6-tetrahydropyridine (MPP+/MPTP)-induced neuronal death through the sustained expression of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) in vitro and in vivo in a Parkinson’s disease model23–25. Since diketopiperazines themselves were reported to exert neuronal protective effects26–28, it is conceivable that the 4-ethyl-2,3-dioxo-1-piperazine moiety, at least partially, contributed to neuronal protection23. Therefore, we anticipate that HDAC1, 2 inhibitors possessing functional groups such as those in 1a, have potential as therapeutic agents for neurodegenerative diseases with a new mechanism of action. These findings prompted us to synthesize the new K-560-related compounds as follows: K-562 (3), K-563 (4), and K-564 (5) with the (4-ethyl-2,3-dioxopiperazine-1-carboxamido) methyl group, and K-852 (6), K-854 (7) and K-856 (8) with a 2,3- or 2,5-diketopiperazinylmethyl group. Furthermore, to analyze the structure activity relationship (SAR) of the derivatives, OP-857 (9) and OP-858 (10) with a 3-oxopiperazinylmethyl group and OP-859 (11) with the 4-ethylpiperazinylmethyl group were prepared. We assessed the potency of these compounds as neuronal protective agents through measuring their toxicity degree to human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Ycells and cell viability in an in vitro model of cerebral ischemia, as well as their selectivity in HDAC1, 2, 3, 8 (Class I) and 6 (Class II) inhibition. We found that 8 with the 2,5-diketopiperazinylmethyl group exerted a promising neuronal protective effect, which was comparable to that of 1a.

Figure 1.

Structures of Known K560-Derivatives and Synthetic Routes of New K-560-Related Compounds 3, 4 and 5. Reagents and Conditions: (a) Pd(PPh3)4, phenylboronic acid, K2CO3, P(o-MeC6H4)3, DME, H2O; (b) Pd(PPh3)4, 3-furanboronic acid, K2CO3, P(o-MeC6H4)3, DME, H2O; (c) Pd(PPh3)4, 2-furanboronic acid, K2CO3, P(o-MeC6H4)3, DME, H2O; (d) p-(chloromethyl) benzoyl chloride, Et3N or Py, THF; (e) potassium phthalimide, KI, DMF; (f) NH2NH2·H2O, EtOH; (g) 4-ethyl-2,3-dioxo-1-piperazinecarbonyl chloride, Et3N, CH2Cl2; (h) TFA, CH2Cl2, then NaHCO3.

Results

Chemistry

In order to identify more potent compounds than K-560 (1a) for neuronal protection, we attempted to synthesize the following two types of compounds: K-560 analogues possessing a 5-phenyl (K-562 (3)), 5-(furan-3-yl) (K-563 (4)), or 5-(furan-2-yl) (K-564 (5)) group in place of the 5-(thien-2-yl) group in 1a, and K-560 derivatives having the following diketopiperazinylmethyl groups in place of the (4-ethyl-2,3-dioxo-1-piperazinecarboxamido) methyl group in 1a: (4-ethyl-2,3-dioxopiperazin-1-yl) methyl (K-852 (6)), (cyclo-L-prolylglycinyl) methyl (K-854 (7))29–31 and (4-methyl-2,5-dioxopiperazin-1-yl) methyl (K-856 (8)). Additionally, OP-857 (9) and OP-858 (10) with a 3-oxopiperazinylmethyl group and OP-859 (11) with the 4-ethylpiperazinylmethyl group were prepared to examine the SAR of these compounds. The K-560 analogues 3, 4, and 5 were prepared starting from tert-butyl 2-amino-4-bromophenylcarbamate, as shown in Fig. 1. This starting material was subjected to Suzuki cross-coupling with phenylboronic acid, 3-furanboronic acid, and 2-furanboronic acid in the presence of tri-o-tolylphosphine, K2CO3, and tetrakis(triphenyl phosphine) palladium, giving biaryls 3a, 4a, and 5a, respectively. These aryls were condensed with p-(chloromethyl) benzoyl chloride in the presence of triethylamine (Et3N), yielding the chlorides 3b, 4b, and 5b, respectively. The chlorides, after conversion to the 4-((1, 3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl) methyl) benzamide derivatives 3c, 4c, and 5c, were reduced with hydrazine to the 4-(aminomethyl) benzamide compounds 3d, 4d, and 5d, respectively. These amines were treated with 4-ethyl-2,3-dioxo-1-piperazinecarbonyl chloride in the presence of Et3N and afforded the condensation products 3e, 4e, and 5e, which were, in turn, Boc-deblocked with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) to yield K-562 (3), K-563 (4), and K-564 (5), respectively. On the other hand, the K-560 derivatives 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11 were synthesized starting from tert-butyl 2-(4-(chloromethyl) benzamido)-4-(thiophen-2-yl) phenylcarbamate, as shown in Fig. 2. This starting material was reacted with 4-ethyl-2,3-dioxo-1-piperazine, cyclo-L-prolylglycine, 1-methylpiperazine-2,5-dione, 1-methyl-piperazin-2-one, tert-butyl 3-oxopiperazine-1-carboxylate and 1-ethylpiperazine in the presence of sodium hydride (NaH) to yield the condensation products 6a, 7a, 8a, 9a, 10a and 11a, which were, in turn, Boc-deblocked with TFA to give the desired K-852 (6), K-854 (7), K-856 (8), OP-857 (9), OP-858 (10) and OP-859 (11), respectively.

Figure 2.

Synthetic Routes of New K-560-Related Compounds 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11. Reagents and conditions: (a) 4-ethyl-2,3-dioxo-1-piperazine, NaH, DMF; (b) cyclo-L-prolylglycine, NaH, DMF; (c) 1-methylpiperazine-2,5-dione, NaH, DMF; (d) 1-methyl-piperazin-2-one, NaH, THF; (e) tert-butyl 3-oxopiperazine-1-carboxylate, NaH, THF; (f) 1-ethylpiperazine, NaH, THF; (g) TFA, CH2Cl2, then NaHCO3.

HDAC1, 2, 3, 6 and 8 inhibition of HDAC inhibitors

Table 1 shows the inhibitory activities (IC50s) of the synthesized compounds together with 1a and TSA against HDAC1, 2, 3, 8 (Class I) and 6 (Class II), which were measured according to the protocol of Enzo Life Sciences. All the compounds except for TSA inhibited preferentially HDAC1 and HDAC2 over HDAC3, 6 and 8. However, their IC50 values of HDAC2 inhibition were (10–26-fold) greater than those of HDAC1 inhibition.

Table 1.

Inhibitory activities of HDAC inhibitors against activation of HDAC1, 2, 3, 8 and 6.

| Compound | IC50 (μM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | Class II | ||||

| HDAC1 | HDAC2 | HDAC3 | HDAC8 | HDAC6 | |

| K-560 (1a) | 0.077 | 0.77 | >25 | >25 | >25 |

| K-562 (3) | 0.063 | 0.81 | >25 | >25 | >25 |

| K-563 (4) | 0.061 | 0.73 | >25 | >25 | >25 |

| K-564 (5) | 0.066 | 1.44 | >25 | >25 | >25 |

| K-852 (6) | 0.068 | 0.98 | >25 | >25 | >25 |

| K-854 (7) | 0.063 | 1.22 | >25 | >25 | >25 |

| K-856 (8) | 0.086 | 1.11 | >25 | >25 | >25 |

| TSA | 0.020 | 0.018 | 0.163 | — | — |

| OP-857 (9) | 0.131 | 1.58 | >25 | >25 | >25 |

| OP-858 (10) | 0.186 | 2.05 | >25 | >25 | >25 |

| OP-859 (11) | 0.092 | 2.43 | >25 | >25 | >25 |

| TSA | 0.032 | 0.024 | 0.451 | 1.18 | 0.204 |

Following two groups of experiments were conducted independently: (one group) HDAC1-3 inhibition of 1a, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8; (the other group) HDAC6, 8 inhibition of 1a, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and HDAC1-3 inhibition of 9, 10, 11. TSA was used as a positive control.

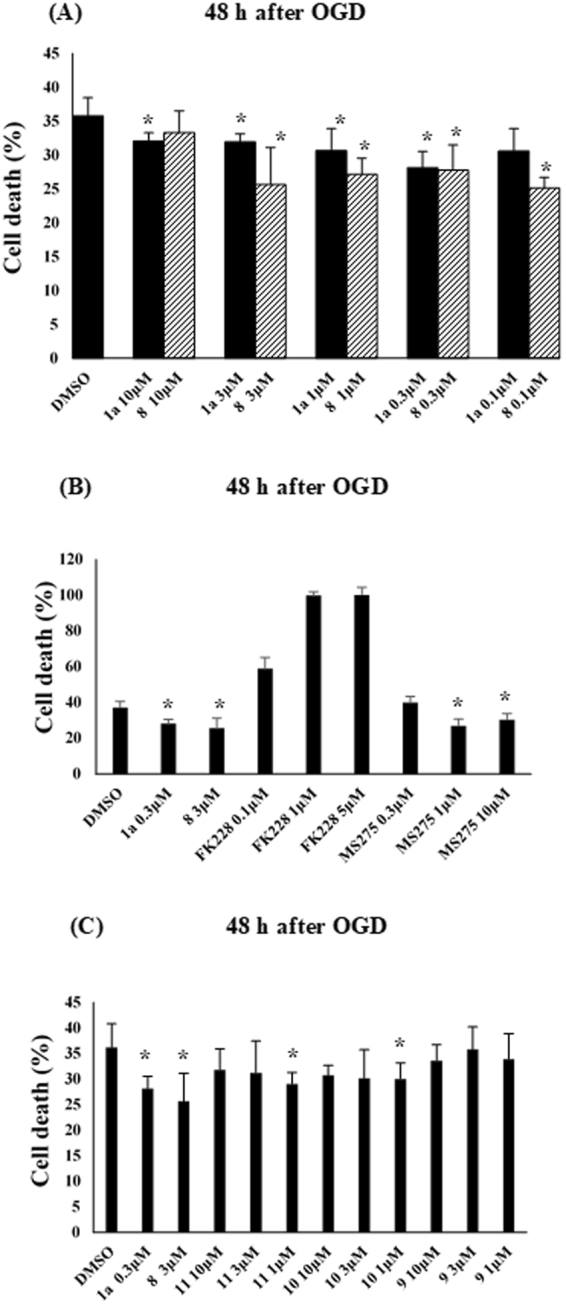

Ameliorating effects of HDAC inhibitors on cell damage after oxygen-glucose deprivation

Primary rat cortical neurons prepared as indicated in the section of Materials and Methods were pre-incubated with a tested compound for 1 h and then subjected to oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) injury for 3 h. Neuronal cell death was assessed by performing a lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay 24 or 48 h after ischemia. Figure 3A shows the percentage of neuronal cell death resulting from incubation with K-560 (1a), K-562 (3), K-563 (4), or K-564 (5) at 1 μM, and Fig. 3B depicts the percentage of cell death resulting from incubation with K-852 (6), K-854 (7), K-856 (8), or K-560 (1a) at 1 μM. The results obtained revealed that 3, 5, 6, and 8, as well as 1a, exerted protective effects (LDH assay in 24 h) against OGD-induced damage. Since K-856 (8) seemingly exerted the most promising protective effects (though with no significant difference between them) (Fig. 3B), its protective activity was compared with that of 1a by performing the LDH assay 48 h after ischemia (Fig. 3C). It is noteworthy that both K-560 (1a) and K-856 (8) maintained a lower percentage of neuronal cell death than the control (0.1%DMSO) even in 48 h. Figure 3D shows the percentage death of neuronal cells which were incubated with the 2-nitro form4 (1b) of K-560 (1a), K-561 (2a), or the 2-nitro form4 (2b) of 2a. None of these compounds exerted protective effects and, instead, they decreased cell viability compared with the control (by the LDH assay 24 h after ischemia). In order to monitor the changes in the protective effects of 1a and 8 with the concentrations, cortical neurons were incubated with them at ranging from 0.1 to 10 μM before OGD-induced injury, respectively, (Fig. 4A). It was substantiated that, although dose-dependency was not clearly observed, 1a and 8 reduced the percentages of cell death at 10–0.3 μM and at 3–0.1 μM (with significant differences vs. control), respectively, and that 8 was more effective than 1a at the lowest concentration (0.1 μM). Furthermore, it is suggested from the comparative experiment (Fig. 4B) with the clinically-used HDAC inhibitors, FK228 (HDAC1,2 selective inhibitor), MS-275 (HDAC Class I inhibitor), as well as 1a and 8, that 1a and 8 are more potent than FK228, since FK228 was more toxic even at 0.1 μM than the control, whereas they have nearly the same level of protective activity as MS-275. Figure 4C indicates that none of the 4-methyl-substituted 3-oxopiperazine form: OP-857 (9), the 4-unsubstituted 3-oxopiperazine-form: OP-858 (10) and the 4-ethylpiperazine-form: OP-859 (11) was effective with significant difference from the control, though compound 10 looked more effective than 9 and 11.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of Percentages of Cell Death in Primary Cultures of Rat Cortical Neurons Exposed to HDAC Inhibitors. Cell death (%) in primary cultures of rat cortical neurons was determined by measuring LDH release 24 h or 48 h after OGD. Cultures were incubated with (A) 1a, 3, 4 or 5 each at 1 μM; (B) 6, 7, 8 or 1a each at 1 μM; (C) 8 or 1a each at 1 μM; (D) 1b, 2a or 2b each at 1 μM, under the conditions noted in the section of Materials and Methods. Each value is the mean ± standard error mean of triplicate measurements. The asterisk denotes a significant difference (*p < 0.05) versus the control (0.1% DMSO).

Figure 4.

Dose-Dependent Evaluation of Percentages of Cell Death in Primary Cultures of Rat Cortical Neurons Exposed to HDAC Inhibitors. Cell death (%) in primary cultures of rat cortical neurons was determined by measuring LDH release 48 h after OGD. Cultures were incubated with (A) 8 or 1a each at 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3 or 10 μM; (B) FK228 (at 0.1, 1 or 10 μM), MS-275 (at 0.3, 1, 10 μM), 1a (at 0.3 μM) and 8 (at 3 μM); (C) 9, 10, 11 (each at 1, 3 or 10 μM), 1a (at 0.3 μM) and 8 (at 3 μM), under the conditions noted in the section of Materials and Methods. Each value is the mean ± standard error mean of triplicate measurements. The asterisk denotes a significant difference (*p < 0.05) versus the control (0.1% DMSO).

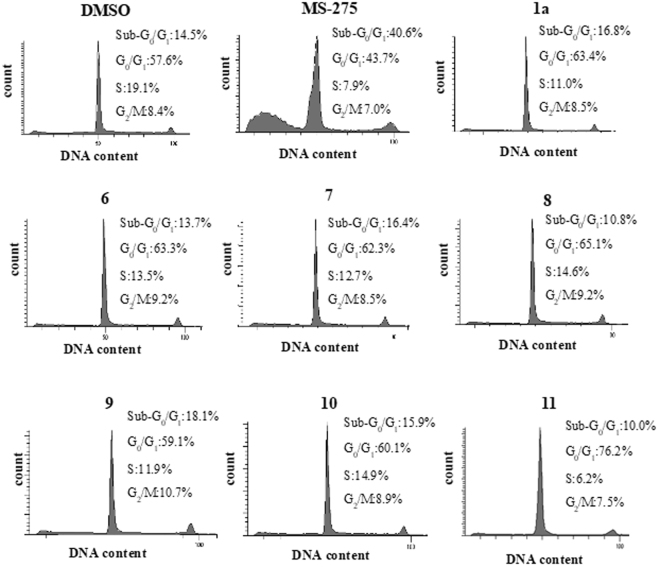

Assessment of toxicity degree of HDAC inhibitors for neuronal SH-SY5Y cells by monitoring cell population of Sub-G0/G1 phase

The toxicity of the HDAC1, 2 inhibitors to SH-SY5Y cells were estimated by monitoring the percentage of population of Sub-G0/G1 phase in the SH-SY5Y cells. Thus, the cells, after treatment with 1a, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10 or 11 for 48 h, were subjected to flow cytometric analyses. As a positive control, MS-275 was used. Figure 5 shows the percentages of the population in the Sub-G0/G1, G0/G1, S and G2/M phase for each compound. Among them, MS-275 showed the highest percent (40.6%) of cell distribution of Sub-G0/G1 phase, whereas the other compounds exhibited more or less the same level of Sub-G0/G1 distribution (10.0–18.1%) as that of the control (14.5%). These results suggest that 8 has a low toxicity to SH-SY5Y cells and is much less toxic than MS-275.

Figure 5.

Assessment of Toxicity Degree of HDAC inhibitors for SH-SY5Y Cells by Flow Cytometry. SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 1a, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10 or 11 for 48 h as indicated in the section of Material and Methods, and their DNA contents were analyzed using flow cytometry. The percentages of the population in the Sub-G0/G1, G0/G1, S and G2/M phase are indicated. 0.1%DMSO was used as a control. The experiment was repeated three times and representative histograms are shown.

Discussion

Three hydroxamate-type pan-HDAC inhibitors have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to date for the treatment of the following cancers: SAHA for the advanced forms of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL)5,6,32; Belinostat (Beleodaq) for refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL)33; Panobinostat (Farydak) for the combinatorial treatment of multiple myeloma34. Furthermore, the cyclic depsipeptide FK228 (Romidepsin) was licensed by the US FDA for the treatment of CTCL5,6,32, and the 2-aminobenzamide-type HDAC inhibitor MS-275 (Entinostat), for breakthrough therapy in the treatment of advanced breast cancers35. On the other hand, HDAC inhibitors have emerged as an attractive therapeutic candidate for neurodegeneration in the last decade36,37 because therapeutic options for neuroprotective therapies in subacute or chronic ischemic stroke currently remain very limited. It is anticipated that HDAC inhibitors may act against chronic neurodegeneration without tumorigenesis because they have been developed as treatment drugs for various cancers. Endovascular therapy after intravenous t-PA has been reported to lead to better functional outcomes38–41. Although pan-HDAC inhibitors such as SAHA and TSA were previously shown to prevent ischemic cell damage and improve functional recovery, they may cause side effects due to the non-selectivity of their HDAC isoforms. Since HDAC1, 2, and 3 are strongly expressed in the central nervous system, a promising strategy may be to develop selective inhibitors of these enzymes in order to assess their effectiveness as a new therapeutic agent for ischemic stroke.

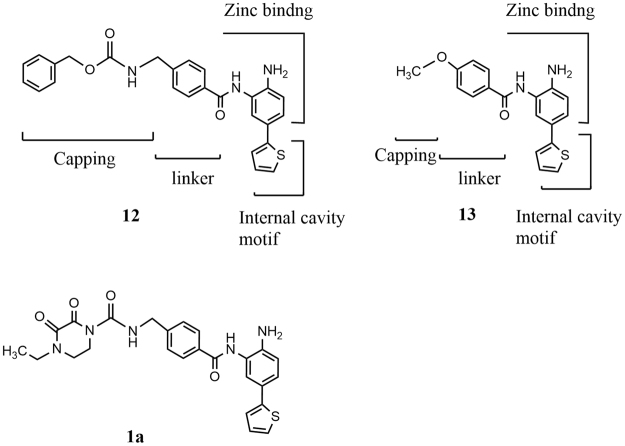

We were encouraged by the result showing that the HDAC1, 2-selective inhibitor K-560 (1a) exerted neuroprotective effects23–25. Therefore, we attempted to synthesize K-560-related compounds in order to assess their inhibitory activities against HDAC1, 2, 3, 8 (Class I) and 6 (Class II) and ameliorating effects on in vitro cerebral ischemia and also to examine their SAR. The results obtained revealed that all the compounds tested preferentially inhibited HDAC1 and 2 though with a 10–26-fold selectivity for HDAC1 over HDAC2. According to the SAR study between 5-thienyl-substituted 2-aminobenzamide HDAC1,2 inhibitors, even truncation (exemplified by 13) of the capping group and linker domain of compound 12 maintained a high selectivity for HDAC1 and HDAC2 versus HDAC3 and HDAC8, but reduced the preference for HDAC1 versus HDAC242 (Fig. 6). It is well known that the cap region of HDAC is predominantly responsible for selectivity43. Based on these findings, it is seems reasonable that our HDAC1,2 inhibitors, typified by 1a, having almost the same size of capping and linker domains as those of 12, showed the preferential inhibition for HDAC1 over HDAC2.

Figure 6.

Structural Regions of 5-Thienyl-Substituted 2-Aminobenzamide type HDAC Inhibitors.

The OGD experiments indicated that the synthesized HDAC1, 2 inhibitors and K-560 (1a) exerted neuronal cell protection except for K-563 (4), K-854 (7), OP-857 (9), OP-858 (10) and OP-859 (11) (Figs 3A,B,C and 4C). It was also revealed that 8 and 1a had the promising neuroprotective activity, but the effect of 8 was higher than or at least equal to 1a. This finding was supported from the comparative OGD experiment with various concentrations of 8 and 1a, i.e., it showed that 8 was still effective at the lowest concentration (0.1 μM) where 1a was not effective (Fig. 4A). Another comparative experiment using the clinically used medicines FK228 (HDAC1, 2 inhibitor) and MS-275 (HDAC Class I inhibitor) suggested that both 8 and 1a have a higher neuroprotective activity than FK228, whereas they possess nearly the same activity as MS-275 (Fig. 4B). Since, however, MS-275 showed much higher percent (40.6%) of distribution of Sub-G0/G1 phase cell (corresponding to apoptotic cell) than those (10.0–18.1%) for other compounds in the flow cytometric analyses of neuronal SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 5), compound 8 is expected to be less toxic than MS-275 to neuronal cells.

Because the cyclo-L-prolylglycinylmethyl group reportedly exhibited both nootropic and anxiolytic activities29, it was unexpected that compound 7, which possesses this group, was not effective. We speculate that a bicyclic diketopiperazine ring such as that in 7 may be less suitable than a monocyclic diketopiperazine ring for interactions with biological molecules due to its bulkiness. Furthermore, since the HDAC1 and 2 inhibition of 1a and 3–11 was comparable (Table 1), it would be inappropriate that only their enzyme inhibition activities have responsibility for the neuroprotective effects. Instead, it is reasonable to assume that the diketopiperazine moieties (capping group) in these compounds are at least partially involved in their neuronal protection, in view of the reports that diketopiperazines themselves had neuroprotective activities26–28. This assumption was supported by the finding that neither the monoketopiperazine-form 9 and 10 nor the piperazine-form 11 showed the neuroprotective effect as much as the diketopiperazine-form 8 and 1a (Fig. 4C).

The 2-nitro derivatives 1b and 2b as well as 2a, having the (4-methylpiperazine-1-carboxamido) methyl moiety, deteriorated cell viability from that with the control (Fig. 3D). The 2-amino group in the 2-amino-5-aryl-benzamide type HDAC inhibitor is known to play a role in chelation with zinc ion at the active site of the HDAC enzyme together with the 2-aminobenzamide-carbonyl, leading to its inhibition. Taken together, the presence of a monocyclic 2,3- or 2,5-diketopiperazine group as well as the HDAC1, 2 inhibition by the 2-aminobenzamide moiety appears to be crucial for the cell survival activity of K-560-related compounds against ischemic damage.

HDAC1 is a key molecular player between neuronal survival and death44,45. HDAC2 abolishes neurodegeneration-associated memory impairments via epigenetic blockade46,47, and mitigates remote fear memories48. In ischemic stroke, the inhibition of both or either HDAC1 and HDAC2 reduce ischemic damage. In neurological disorders, it is currently unclear which isozyme of HDAC enzymes needs to be inhibited because the type of HDAC being activated varies depending on the distinct pathophysiology, associated cell types, or the degree and severity of tissue damage. Further studies are underway to assess the validity of K-560-related compounds for CNS therapeutics against neurodegenerative diseases and stroke.

Materials and Methods

The experimental protocol was approved by the Committee of Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Kansai University, and Osaka University of Pharmaceutical Sciences.

Synthesis

The syntheses and physicochemical properties of HDAC inhibitors are provided as Supplementary information available with this article online.

Biology

Assessment of HDAC inhibition activities

The inhibitory activities of compounds against HDAC1, 2, 3, 8 (Class I) and 6 (Class II) were measured utilizing the Fluorometric Drug Discovery Assay Kit BML-AK511 (HDAC1), BML-AK 512 (HDAC2), and BML-AK 531 (HDAC3), BML-SE145-0100 (HDAC8) and BML-SE508-0050 (HDAC6) (supplied from Enzo Life Sciences). The following two groups of experiments were conducted independently: (one group) HDAC1-3 inhibition of 1a, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8; (the other group) HDAC6, 8 inhibition of 1a, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11 and HDAC1-3 inhibition of 9, 10, 11. TSA was used as a positive control in each group. Each assay was independently repeated two times with duplicate measurements, and a similar value was obtained for each compound.

Cell culturing

Human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y (ATCC CRL-2266) was cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) at 37 °C in a 95% air and 5% CO2 humidified incubator. Cells were routinely subcultured when confluent.

Animals

Wistar rats (Charles River) were used in this study. The experimental protocol was approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine. Animals were kept four per cage under a 12 h light/dark cycle and standard housing conditions with ad libitum access to food and water before and after all procedures. Animal care was provided according to the Osaka University Medical School Guideline for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Animal surgeries and experimental procedure were approved by the Osaka University Medical School Animal Care and Use Committee. All experiments were conducted according to the National Research Council’s guidelines.

Primary cortical cultures

Primary cultures of rat cortical neurons were obtained as described previously49,50. Briefly, neuronal cultures were prepared from the cortex of embryonic day 16 (E16) rat embryos. Cells were dissociated with papain (papain dissociation system; Worthington) and plated onto 12-well plates, 4-well plates, and 60-mm dishes (Falcon, Becton Dickinson), or 4-chamber glass slides (Falcon) coated with polyethylenimine. Cells at a final concentration of 7.0 × 105 cells/mL were cultured in high-glucose DMEM (Sigma) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Invitrogen), 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin sulfate. Twenty-four hours after seeding, the medium was changed to Neurobasal medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with B-27 (Invitrogen). Cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 and used after 10–11 days in vitro when most cells showed a neuronal phenotype.

Oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD)

OGD was performed by placing cultures in a 37 °C incubator housed in an anaerobic chamber as previously described49,50. Cultures were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and incubated with glucose-free Eagle’s balanced salt solution (Biological Industries). Cultures were subjected to an anaerobic environment of 95% and N2/5% CO2, producing an O2 partial pressure of 10–15 Torr, as measured with an oxygen microelectrode at 3 h. OGD was terminated by bringing the cultures back to the original medium and placing them in a normoxic chamber.

Cell viability Assays

Before OGD, cortical neurons were treated with the following chemicals each at 1 μM for 1 h: K-560 (1a), K-562 (3), K-563 (4) and K564 (5) (Fig. 3A); K-560 (1a), K-852 (6), K-854 (7) and K-856 (8) (Fig. 3B); 1a and 8 (Fig. 3C); 1b, 2b and 2a (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, cortical neurons were treated for 1 h with 1a and 8 each at 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3 or 10 μM (Fig. 4A), with FK228 (Selleck Chemicals) (at 0.1, 1 or 10 μM), MS-275 (at 0.3, 1, 10 μM), 1a (at 0.3 μM) and 8 (at 3 μM) (Fig. 4B) and with OP-857 (9), OP-858 (10), OP-859 (11) (each at 1, 3 or 10 μM), 1a (at 0.3 μM) and 8 (at 3 μM) (Fig. 4C). As the control, 0.1%DMSO was used in each experiment. Neuronal injury was measured 24 h or 48 h after OGD by measuring LDH activity using a cytotoxicity detection kit (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany). Collected culture medium was centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min before assaying according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In a sister culture, 100% cell death was induced with 2 mmol/L NMDA. The relative assessments of neuronal injury were normalized by comparisons with 100% cell death.

Analysis of DNA histogram by flow cytometry

SH-SY5Y cells were plated onto 60-mm diameter dishes (1.0 × 106/dish). After incubation for 24 h, the cells were washed twice with the serum-free medium (1 mL) and suspended with the serum-free medium (5 mL) for 24 h. After removal of the medium, the cells were washed twice with the serum-free medium (1 mL) and incubated in the serum-free medium (5 mL) with a test compound (10 μM) for another 48 h. The adherent cells were treated with 0.25% trypsin (Invitrogen) and combined with the floating cells. All the cells were treated with a Cycle Test Plus DNA reagent Kit (Catalog No. 340242, Becton Dickinson). DNA content was measured with a FACSTMCant II. (Becton Dickinson).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error mean. Statistical analyses were performed using a one-way analysis of variance (SPSS). A p-value of less than 0.05 denotes a significant difference.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Part of this work was supported by the following grants: Grant-in-Aid for challenging Exploratory Research (16K15317) from ‘Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology’ – ‘Japan,’ and Smoking Research Foundation (T.S.).

Author Contributions

S.U., Y.H., and T.S. performed the research and drafted the manuscript; S.U., H.M., and M. T. interpreted data and approved the final manuscript; S.U. and Y.H. designed the compounds; Y.H., A.H., and G.K. synthesized the compounds; Y.H. and T.S. performed HDAC1, 2, 3 inhibition assays; T.S., H.K., C.C.J., and K.N. prepared rat primary cortical cultures and conducted OGD assays.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Yoshiyuki Hirata, Tsutomu Sasaki and Shinichi Uesato contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-19664-9.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Tsutomu Sasaki, Email: sasaki@neurol.med.osaka-u.ac.jp.

Shinichi Uesato, Email: suesato@gaia.eonet.ne.jp.

References

- 1.Schweizer S, Meisel A, Märschenz S. Epigenetic mechanisms in cerebral ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:1335–1346. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKinsey TA. Isoform-selective HDAC inhibitors: Closing in on translational medicine for the heart. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2011;51:491–496. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prince HM, Bishton MJ, Harrison SJ. Clinical studies of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:3958–3969. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirata Y, et al. Anti-tumor activity of new orally bioavailable 2-amino-5-(thiophen-2-yl) benzamide-series histone deacetylase inhibitors, possessing an aqueous soluble functional group as a surface recognition domain. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:1926–1930. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marks PA, Miller T, Richon VM. Histone deacetylases. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2003;3:344–351. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4892(03)00084-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Acharya MR, Sparreboom A, Figg WD. Rational development of histone deacetylase inhibitors as anticancer agents: A Review. Clin. Pharmacol. Res. 2005;68:917–932. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.014167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drummond DC, et al. Clinical development of histone deacetylase inhibitors as anticancer agents. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2005;45:495–528. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minucci S, Pelicci PG. Histone deacetylase inhibitors and the promise of epigenetic (and more) treatments for cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:38–51. doi: 10.1038/nrc1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bolden JE, Peart MJ, Johnstone RW. Anticancer activities of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006;5:769–784. doi: 10.1038/nrd2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dokmanovic M, Clarke C, Marks PA. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: Overview and perspectives. Mol. Cancer Res. 2007;5:981–989. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu WS, Parmigiani RB, Marks PA. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: molecular mechanisms of action. Oncogene. 2007;26:5541–5552. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marks PA, Xu WS. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: Potential in cancer therapy. J. Cell. Biochem. 2009;107:600–608. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Methot JL, et al. Exploration of the internal cavity of histone deacetylase (HDAC) with selective HDAC1/HDAC2 inhibitors (SHI-1:2) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:973–978. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moradei OM, et al. Novel aminophenyl benzamide-type histone deacetylase inhibitors with enhanced potency and selectivity. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:5543–5546. doi: 10.1021/jm701079h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Witter DJ, et al. Optimization of biaryl selective HDAC1&2 inhibitors (SHI-1:2) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:726–731. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson KJ, et al. Phenylglycine and phenylalanine derivatives as potent and selective HDAC1inhibitors (SHI-1) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:1859–1863. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Methot JL, et al. SAR profiles of spirocyclic nicotinamide derived selective HDAC1/HDAC2 inhibitors (SHI-1:2) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:6104–6109. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kattar SD, et al. Parallel medicinal chemistry approaches to selective HDAC1/HDAC2 inhibitor (SHI-1:2) optimization. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19:1168–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.12.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu Y, et al. Investigation on the isoform selectivity of histone deacetylase inhibitors using chemical feature based pharmacophore and docking approaches. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010;45:1777–1791. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heidebrecht RW, Jr., et al. Exploring the pharmacokinetic properties of phosphorus-containing selective HDAC 1 and 2 inhibitors (SHI-1:2) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19:2053–2058. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stolfa DA, et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of 2-aminobenzanilide derivatives as potent and selective HDAC inhibitors. ChemMedChem. 2012;7:1256–1266. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201200193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uesato, S. & Hirata, Y. Proceedings of Frontiers in Medicinal Chemistry (FMC), P172, Antwerp, Belgium September 14–16 (2015).

- 23.Uesato, S., Hirata, Y. & Sasaki, T. Potential application of 5-aryl-substituted 2-amino- benzamide type of HDAC1/2-selective inhibitors to pharmaceuticals. Curr. Pharm. Des. 22, 10.2174/1381612822666161208143417 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Choong CJ, et al. A novel histone deacetylase 1 and 2 isoform-specific inhibitor alleviates experimental Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2016;37:103–116. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mochizuki, H. et al. International Application No. PCT/JP2015/075660.

- 26.Faden AI, Movsesyan VA, Knoblach SM, Ahmed F, Cernak I. Neuroprotective effects of novel small peptides in vitro and after brain injury. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49:410–424. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guan J, et al. Peripheral administration of a novel diketopiperazine, NNZ 2591, prevents brain injury and improves somatosensory-motor function following hypoxia-ischemia in adult rats. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53:749–762. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cornacchia C, et al. 2, 5-Diketopiperazines as neuroprotective agents. Mini-Reviews Med. Chem. 2012;12:2–12. doi: 10.2174/138955712798868959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kolyasnikova KN, Vichuzhanin MV, Konstantinopol’skii MA, Trofimov SS, Gudasheva TA. Synthesis and pharmacological activity of analogs of the endogenous neuropeptide cycloprolylglycine. Pharm. Chem. J. 2012;46:96–102. doi: 10.1007/s11094-012-0741-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Narkevich VB, Ovchinnikova IP, Klodt PM, Kudrin VS. The effects of himantane and cycloprolylglycine on the enzymatic linkage of monoamine synthesis in the rat brain. Neurochem. J. 2012;6:272–277. doi: 10.1134/S1819712412040101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lo´pez-Rodrı´guez ML, et al. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of a new model of arylpiperazines. 8. Computational simulation of ligand-receptor interaction of 5-HT1AR agonists with selectivity over α1-adrenoceptors. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:2548–2558. doi: 10.1021/jm048999e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnstone RW. Histone-deacetylase inhibitors: Novel drugs for the treatment of cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2002;1:287–299. doi: 10.1038/nrd772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee HZ, et al. FDA Approval: Belinostat for the treatment of patients with relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015;21:2666–2670. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ratner M. FDA approves three different multiple myeloma drugs in one month. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:126–126. doi: 10.1038/nbt0216-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinello R, et al. New and developing chemical pharmacotherapy for treating hormone receptor-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2016;17:2179–2189. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2016.1236914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kazantsev AG, Thompson LM. Therapeutic application of histone deacetylase inhibitors for central nervous system disorders. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008;7:854–868. doi: 10.1038/nrd2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Langley B, Brochier C, Rivieccio MA. Targeting histone deacetylases as a multifaceted approach to treat the diverse outcomes of stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:2899–2905. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.540229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berkhemer OA, et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goyal M, et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:1019–1030. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campbell BCV, et al. Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke with perfusion-imaging selection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:1009–1018. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saver JL, et al. Stent-retriever thrombectomy after intravenous t-PA vs. t-PA alone in stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:2285–2295. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1415061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bieliauskas AV, Pflum MKH. Isoform-selective histone deacetylase inhibitors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:1402–1413. doi: 10.1039/b703830p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Falkenberg KJ, Johnstone RW. Histone deacetylases and their inhibitors in cancer, neurological diseases and immune disorders. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014;13:673–691. doi: 10.1038/nrd4360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim D, et al. Deregulation of HDAC1 by p25/Cdk5 in neurotoxicity. Neuron. 2008;10(60):803–817. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bardai FH, Price V, Zaayman M, Wang L, D’Mello SR. Histone deacetylase-1 (HDAC1) is a molecular switch between neuronal survival and death. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:35444–35453. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.394544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guan JS, et al. HDAC2 negatively regulates memory formation and synaptic plasticity. Nature. 2009;459:55–60. doi: 10.1038/nature07925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gräff J, et al. An epigenetic blockade of cognitive functions in the neurodegenerating brain. Nature. 2012;483:222–226. doi: 10.1038/nature10849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gräff J, et al. Epigenetic priming of memory updating during reconsolidation to attenuate remote fear memories. Cell. 2014;156:261–276. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goldberg MP, Choi DW. Combined oxygen and glucose deprivation in cortical cell culture: calcium-dependent and calcium-independent mechanisms of neuronal injury. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:3510–3524. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03510.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sasaki T, et al. SIK2 is a key regulator for neuronal survival after ischemia via TORC1-CREB. Neuron. 2011;69:106–119. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.