Abstract

The biofilm-forming-capability of Helicobacter pylori has been suggested to be among factors influencing treatment outcome. However, H. pylori exhibit strain-to-strain differences in biofilm-forming-capability. Metabolomics enables the inference of spatial and temporal changes of metabolic activities during biofilm formation. Our study seeks to examine the differences in metabolome of low and high biofilm-formers using the metabolomic approach. Eight H. pylori clinical strains with different biofilm-forming-capability were chosen for metabolomic analysis. Bacterial metabolites were extracted using Bligh and Dyer method and analyzed by Liquid Chromatography/Quadrupole Time-of-Flight mass spectrometry. The data was processed and analyzed using the MassHunter Qualitative Analysis and the Mass Profiler Professional programs. Based on global metabolomic profiles, low and high biofilm-formers presented as two distinctly different groups. Interestingly, low-biofilm-formers produced more metabolites than high-biofilm-formers. Further analysis was performed to identify metabolites that differed significantly (p-value < 0.005) between low and high biofilm-formers. These metabolites include major categories of lipids and metabolites involve in prostaglandin and folate metabolism. Our findings suggest that biofilm formation in H. pylori is complex and probably driven by the bacterium’ endogenous metabolism. Understanding the underlying metabolic differences between low and high biofilm-formers may enhance our current understanding of pathogenesis, extragastric survival and transmission of H. pylori infections.

Introduction

Bacterial biofilm constitutes of a community of single or multiple species bacteria adhering onto any surface and encasing in an exopolysaccharide matrix1–3. The ability of unicellular bacteria to function together as a multicellular population through the formation of biofilm provides survival advantage to the bacterial population as a whole2,4 has its merit.

Helicobacter pylori is a bacterial pathogen that has been strongly associated with various gastric diseases ranging from chronic gastritis to mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma and gastric adenocarcinoma5. Interestingly, the organism has been demonstrated to form biofilm in vitro6–11. In addition, H. pylori biofilm has been demonstrated in the stomach of C57Bl/6J mice6 as well as the human stomach7,10. Furthermore, we recently demonstrated that H. pylori has the ability to form biofilm on vegetables, which is a common food source for human, potentially plays an important role in its survival and transmission of in the extragastric environment12. As biofilm has been demonstrated to decrease susceptibility of the biofilm-forming bacteria to antibiotics13,14, controlling and preventing biofilm formation by H. pylori may contribute to successful eradication of H. pylori. Recent studies unveiled the complexity the molecular mechanisms underlying H. pylori biofilm formation15,16. H. pylori biofilm formation has been found to involve the initiation of multiple mechanisms in flagella movement, bacterial virulence, signal transduction and regulation16, and regulated by the combined effect of multiple genetic factors15.

Study by Beale et al.17 on the biofilm metabolomics in water distribution revealed that through the analysis of the metabolites consumed or excreted as a result of metabolic activities, the biofilm activity could be elucidated. Metabolites are the results of the interaction of the microbial genome with its environment where the metabolites are an integral part of any cellular regulatory systems18. In addition, the study of metabolites enables the understanding of biofilm developmental process and bacterial molecular components which are important for establishing the mutual association of biofilm formation19–22.

Metabolomics has been widely applied to interrogate the free-floating planktonic and adhering biofilm lifestyles of various bacteria such as Acinetobacter baumannii23, Salmonella Typhimurium24, Vibrio fischeri20 and Staphylococcus aureus22. Importantly, Booth et al.25 using the metabolomic approach demonstrated that metabolic changes in response to copper exposure were found to be significantly different in Pseudomonas fluorescens biofilms compared to planktonic cultures. However, metabolomic differences between low and high biofilm-forming H. pylori have not been investigated. To better understand the factors involved in the biofilm formation of H. pylori, this study used the metabolomic approach via liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS). The data was then analyzed using MassHunter Qualitative Analysis software to identify the differences between metabolomics profiles of low and high biofilm-forming H. pylori clinical strains. We hypothesized that low and high biofilm-forming capability of H. pylori under a particular condition is determined by their endogenous metabolic capability. In general, biofilm formation could be readily detected by the third day in in-vitro cultures of high biofilm-forming H. pylori strains. Hence, in this study, bacterial metabolites of pre-biofilm H. pylori cultures (i.e. day 0 to 3) were analyzed to identify metabolites that may influence the initiation of biofilm formation.

Results

H. pylori biofilm

From our earlier studies, H. pylori clinical strain UM032, UM065, UM066, and UM067 were shown to be high biofilm-forming strains while UM038, UM054, UM084, and UM114 were low biofilm-forming strains12,26. The bacterial strains were cultured on chocolate blood agar plates, then the 3-day old H. pylori cultures were suspended in broth media for the development of biofilm (i.e. day 0). Biofilm formation was observed at the air-liquid interface of cultures of the high biofilm-forming stains but not in the low biofilm-forming stains by day 3. Scanning electron micrographs of the day 3 biofilm of a high biofilm-forming H. pylori strain are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. Based on these findings, the metabolomic study was designed to study the differences in bacterial metabolism between high biofilm-forming strains and low biofilm-forming strains from day 0 to 3.

Global metabolomics profile

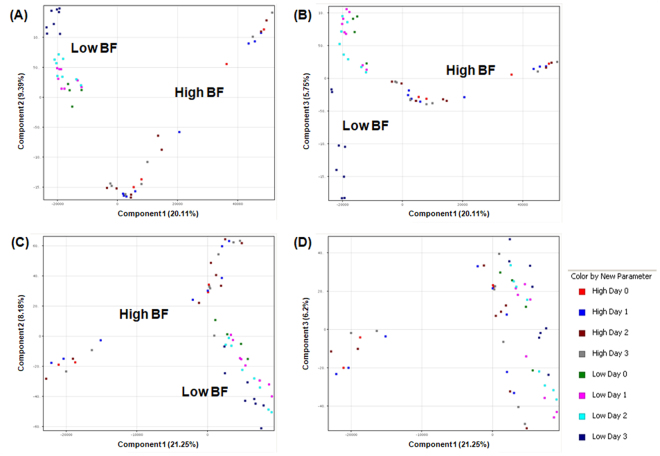

The unsupervised principal component analysis (PCA), which “condenses information contained in a large number of original variables into a smaller set of new composite dimensions with minimum loss of information”, was for quality control of samples27. When PCA using Euclidean distance was applied to compare the global metabolomic profiles (i.e. all molecular features without filtering) of the 8 individual strains, low and high biofilm-forming H. pylori strains partition into 2 well-separated groups based on their distinctive profiles on the PCA plots (Fig. 1A–C). The grouping of these H. pylori strains corresponds to their biofilm-forming capability, irrespective of age of culture. Replicates within a group should cluster together. On the other hand, the PCA plot generated based on compounds acquired in the negative ionization mode using principal components 1 and 3 failed to separate between low and high biofilm formers (Fig. 1D). Hence, clustering pattern shows that separation between low and high biofilm-formers was more differentiated based on positively-acquired compounds (Fig. 1A and B) compared to compounds acquired in negative ionization mode (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Two-dimensional principal component analysis (PCA) of 56 samples based on global metabolomic profiles. The PCAs were generated using MassHunter Mass Profiler Professional (MPP) software. There were 28 low and 28 high biofilm-forming samples. Independent replicates are available for Day 1 to 3 samples. Axes represent the principle components of the PCA and the numbers indicate the percentage of variance that is captured by each component. H. pylori strains formed distinct clusters on the basis of features acquired in positive ionization mode using (A) components 1 (20.11%) and 2 (9.39%), and components 1 (20.11%) and 3 (5.75%) (B). H. pylori strains formed distinct clusters on the basis of molecular features acquired in negative ion mode using components 1 (21.25%) and 2 (8.18%) (C) but not when components 1 (21.25%) and 3 (6.2%) was used (D). The scores shown by the axes scales are used to check data quality.

Using one-way ANOVA, a total of 1650 molecular features (1454 features were identified in the positive ionization mode and 196 features in the negative ionization mode) were identified to be significantly different (p-value < 0.005) between low and high biofilm-formers from day 0 to 3. After removing redundant molecular features that appeared in both positive and negative lists, 1468 features remained. Notably, 1434 features were increased in low biofilm-formers. In contrast, only 34 features were increased in high biofilm-formers. Thus, the metabolomes of low biofilm-forming H. pylori were demonstrated to be more diversity compared to high biofilm-forming H. pylori. Among these features, 351 features (330 features were increased in low biofilm-formers and only 21 features were increased in high biofilm-formers) matched metabolites in the Agilent METLIN Accurate Mass-Personal Metabolite Database and Library (AM-PCDL) database based on accurate mass, isotope ratios, abundances and spacing The 351 metabolites identified are listed in Supplementary Table S1. The mean number of metabolites per sample was 94 (30–176) for the high biofilm forming group and 317 (281–341) for the low biofilm forming group. The number of metabolites per low biofilm forming sample was significantly higher than the number of metabolites per high biofilm forming sample (p-value < 0.005).

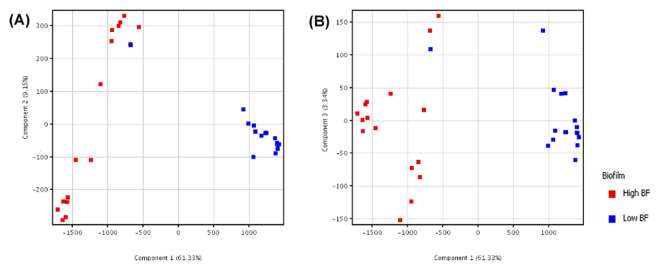

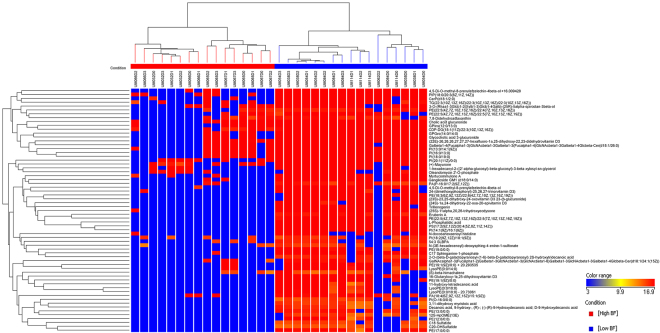

After statistically filtering out non-differential metabolites based on one-way ANNOVAR, metabolites acquired using positive and negative ionization modes were combined for further analysis. PCA plots of differential molecular features show that the metabolomic profiles of high biofilm-formers display a more spread out pattern suggesting that they were more heterogeneous in nature (Fig. 2). In contrast, low biofilm-formers, which clustered closer together on the PCA plots, were more homogenous. Similarly, the low and high biofilm-formers are clearly illustrated as two distinct groups in the heat map by the metabolites that were significantly different (p-value < 0.005) (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Two-dimensional principal component analysis (PCA) based on 351 significantly different metabolites. The PCAs were generated using MPP. Legend: red (high biofilm-formers, N = 28) and blue (low biofilm-formers, N = 28). Independent replicates are available for Day 1 to 3 samples. Axes represent the first three principle components of the PCA and the numbers indicate the percentage of variance that is captured by each component. (A) Shows the H. pylori strains separated based on components 1 (61.33%) and 2 (9.15%), while (B) shows the strains separated based components 1 (61.33%) and 3 (3.34%).

Figure 3.

Heat map and clustering presenting metabolomic profiles of low and high biofilm-formers based on 65 significantly different lipids. The heat maps and clustering based on Euclidean distance were generated using MPP. Features with p-value < 0.005 were considered to be significantly different between low and high biofilm-formers. Details of these lipids are listed in Suppl. Table S1.

Among the 351 metabolites identified, 65 significantly differentiating metabolites were lipids belonging to different categories. The heat map profile (Fig. 3) of these 65 lipids revealed that lipids were enriched in low biofilm-formers as compared to the high biofilm-formers. In contrast, few metabolites were increased in high biofilm-formers relative to low biofilm-formers. This finding indicates distinct differences between the metabolome of low and high biofilm-formers, which is consistent with the PCA plots. The metabolome of low biofilm-formers was also more complex than that of high biofilm-formers.

Biofilm-associated metabolites and pathway analysis

Among metabolites that were enriched in low biofilm-formers were 65 lipids of different categories, comprising of 26 glycerophospholipids, 10 sterol lipids, 7 sphingolipids, 6 fatty acyls, 5 polyketides, 3 prenol lipids, 3 lysophosphatidylethanolamine, 2 phosphatidylglycerides, 2 glycerolipids, and a glycosphingolipid (Supplementary Table S2). Notably, (24S)-1α,24-dihydroxy-22-oxa-20-epivitamin D3, 16-glutaryloxy-1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, 24-(dimethoxyphosphoryl)-25,26,27-trinorvitamin D3, (22E)-26,26,26,27,27,27-hexafluoro-1α,25-dihydroxy-22,23-didehydrovitamin D3, and (23S)-23,25-dihydroxy-24-oxovitamin D3 23-(β-glucuronide) are derivatives of vitamin D3.

In addition to lipids, non-lipid metabolites were also higher in low biofilm-formers. These include 5-oxoavermectin “2b” aglycone (KEGG C11954), avermectin B2b monosaccharide (KEGG C11957) and avermectin A2b monosaccharide (KEGG C11958), which are involved in the biosynthesis of 12-, 14- and 16-membered macrolides (map00522). Alkaloids, terpenoids, and triterpene glycosides were increased in low biofilm-formers.

Interestingly, N(6)-(octanoyl)lysine, a modified lysine amino acid that is normally found in acyl carrier protein, was also significantly higher in low biofilm formers (p-value = 6.49E-33). L-arginine (KEGG C00062), D-arginine (KEGG C00792) and p-coumaroylputrescine (a metabolite of arginine metabolism; KEGG C18326) were mapped to arginine and proline metabolism (map00330) and/or D-arginine and D-ornithine metabolism (map00522). Phenylacetaldehyde (KEGG C00601) and Phenylethylamine (KEGG C05332) were mapped to phenyalanine metabolism (map00360). Similarly, lignans (polyphenolic substances derived from phenylalanine) were also higher in low biofilm-formers.

Notably, L-Arginine (KEGG C00062), Cilastatin (KEGG C01675) and Neomycin B (KEGG C01737) were mapped to antibiotics biosynthesis (map00331, map 00524 and map01130). A sterol lipid, cholic acid glucuronide (KEGG C03033) and Indinavir (KEGG C07051) were mapped to bile secretion (map04976). These metabolites were also found in the low biofilm-formers but not the high-biofilm formers.

In contrast, 5-methyltetrahydrofolic acid (5-methyl-THF; KEGG: C00440; HMP: HMDB1396) was significantly increased in high biofilm-formers by 3.3-fold (p-value = 4.29E-07).

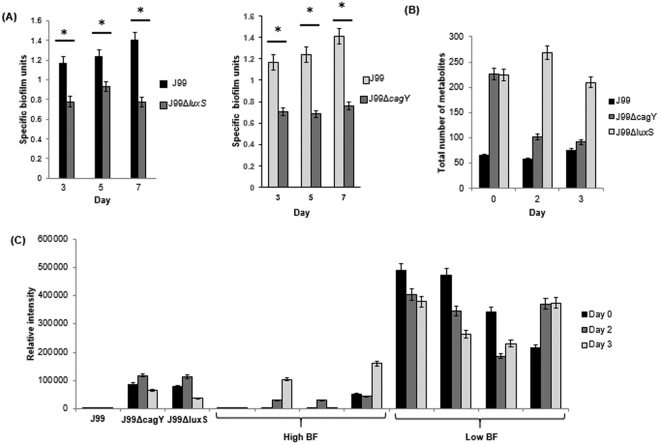

H. pylori J99ΔluxS and J99ΔcagY

H. pylori J99ΔluxS mutant strain was created in the laboratory of Associate Professor Hardie Kim at the University of Nottingham while J99ΔcagY mutant strain was generated as part of another study. Crystal violet assay was performed as described previously12,26. Both J99ΔluxS and J99ΔcagY mutant strains were found to have significantly reduced biofilm-forming abilities compared to wild-type J99 (p-value < 0.05; indicated by*) (Fig. 4A). Associated with reduced biofilm-forming abilities of the mutant strains was the observation of increased number of metabolites produced by the mutant strains compared to the isogenic wild-type J99 (p-value < 0.05; indicated by*) (Fig. 4B). Among the metabolites detected in only the mutant strains but not found in wild-type J99 was ceramide phosphoinositols (PI-Cer(t18:0/18:0(2OH))) or N-(2-hydroxyoctadecanoyl)-4R-hydroxysphinganine-1-phospho-(1′-myo-inositol) (LMP ID LMSP03030037), which is a phosphosphingolipid. Interestingly, PI-Cer(t18:0/18:0(2OH)) was high in low biofilm-forming strains but low or not detected in high biofilm-forming strains (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

(A) Specific biofilm unit of wild-type H. pylori J99, J99ΔluxS and J99ΔcagY determined by crystal violet assay. (B) Comparison of number of metabolites detected by LC-MS per sample for H. pylori J99, J99ΔluxS and J99ΔcagY. *Represents p-value < 0.05 comparing between wild-type and mutants. (C) Comparing the relative abundance of PI-Cer(t18:0/18:0(2OH)) in H. pylori J99, J99ΔluxS, J99ΔcagY, high biofilm-forming clinical strains and low biofilm-forming strains.

Discussion

Metabolomics has been employed to investigate the differences between planktonic cultures and biofilms of various microbes23,25. This study has taken a step further to utilize metabolomics in distinguishing the metabolomes of H. pylori with low and high biofilm-forming capabilities. From day 0 to day 3, both high and low biofilm formers were still predominantly in the planktonic form. In contrast, for cultures after day 3, the metabolomic profile of high biofilm forming H. pylori is expected to be the combined effects of both planktonic and biofilm bacteria while the profile of low biofilm formers is due solely from planktonic bacteria. Therefore, only cultures from day 0 to day 3 were analyzed in order to minimize the confounding effect of biofilm bacteria in high biofilm formers. Comparative metabolomics of pre-biofilm forming cultures from day 0 to day 3 enable the identification of metabolites potentially associated with biofilm initiation and development. Our study showed distinct separation of high from low biofilm-formers based on PCA plots and identification of differential metabolites associated with these two groups of H. pylori. It also demonstrated the potential of metabolomics for use in the study of biofilm development.

It is not unexpected that low biofilm-formers probably have greater tendency to remain in their free-floating planktonic state than high biofilm-formers. The study shows that the low biofilm-forming H. pylori strains produced larger amount and more diverse types of metabolites indicating higher endogenous metabolic activities (especially lipid metabolism) compared to their high biofilm-forming counterparts regardless of age of cultures (day 0–3). Consistent with this observation, the inactivation of two genes (luxS and cagY) were demonstrated to reduce biofilm forming abilities and associated with increase in type of metabolites detected. Thus, metabolomics result in this study suggests that biofilm-forming capability of H. pylori strains may be influenced by the endogenous metabolic activities of the bacterium. It has been proposed earlier by Costerton et al.3 that adhered-bacteria (akin to biofilm-formers), are less metabolically active than planktonic bacteria.

The metabolites that were increased in the low biofilm-formers were of different categories of lipids, namely glycerophospholipids, sterol lipids, sphingolipids, fatty acyls, polyketides, prenol lipids, lysophosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylglycerides, glycerolipids, and glycosphingolipid. It is interesting to note that there has been no report of these lipids relating to H. pylori biofilm formation. However, an unpublished study carried out earlier in our lab (NUS) found that commercial full cream milk sustained the culturability of H. pylori for longer duration than low fat milk at 4 °C. H. pylori spiked into full cream milk remained culturable for as long as 72 hours while those in low fat milk completely loss their culturability after 4–8 hours at 4 °C (data not shown). Full cream milk contained 2- to 3-fold higher fat content compared to low fat milk. Consistently, BHI broth supplemented with fat extracted from milk was found to sustain the culturability of H. pylori for a longer period than just BHI alone at 4 °C. These findings indicate that lipids may contribute towards sustaining the viability of H. pylori or maintaining the bacterium in its planktonic state. Thus, endogenous biosynthesis of lipids by certain H. pylori strains may be associated with low biofilm-formation.

Phospholipids and sphingolipids are important components of cell membranes. These lipids (predominately long chain phospholipids and sphingolipids) are increased in low biofilm-formers indicating that the membrane of low biofilm-formers may have higher lipid stability and lower membrane fluidity. In addition, sphingolipids have previously been reported to inhibit the adherence of Streptococcus mutans to hydroxyapatite surfaces28. Hence, it is postulated that the presence of higher abundance of sphingolipids in low biofilm-formers may be unfavorable for bacteria-bacteria and bacteria-surface adherence necessary for the initiation of biofilm formation.

It has been established that many lipids (especially fatty acids) may be important in cell signaling that regulates a wide range of cellular functions29. These signals have been identified in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria as a unique chemical class of quorum sensing signals29. Various bacterial activities, such as in intra-species, inter-species and cross-kingdom communications that regulate bacterial growth, virulence, motility, polymer production, biofilm development, biofilm dispersion, and persistence, can be linked to fatty acid signaling30–33.

N(6)-(Octanoyl)lysine, which participates in the lipoic acid metabolism downstream of fatty acid biosynthesis, was found to be higher in low biofilm-formers. Degradation of acyl carrier protein or of lipoate-derivatized proteins will lead to free N(6)-(Octanoyl)lysine. lipoyl(octanoyl) transferase (EC 2.3.1.181). Interestingly, Helicobacter pylori has not been shown to posses lipoyl(octanoyl) transferase (EC 2.3.1.181) or lipoyl synthase (EC 2.8.1.8). However, it cannot be ruled that other enzyme(s) may perform similar functions to catalyze the transfer of endogenously produced octanoic acid from octanoyl-acyl-carrier-protein onto the lipoyl domains of lipoate-dependent enzymes.

Myrtucommulone A, a polyketide, was also found to be increased in low biofilm-formers compared to their high biofilm-forming counterparts. Myrtucommulone A is a lipophilic carboxylic acid with fatty acid-like character; they may bind to microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 (mPGES-1) as polyunsaturated fatty acids and inhibit the pro-tumorigenic prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) synthesis34,35. Prostaglandin is found to be synthesized during Candida albicans biofilm formation36,37. The inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis had greatly reduced fungal adhesion and detachment of mature biofilm38,39. Although H. pylori does not synthesize prostaglandin, it cannot be ruled out that myrtucommulone A synthesis by low biofilm-forming H. pylori strains may inhibit gastric prostaglandin synthesis, thereby influencing H. pylori-induced pathogenesis.

Results from the current study showed that biofilm formation in H. pylori may be influenced by its lipidome suggesting there may be a difference in membrane composition of low and high biofilm-formers. Notably, it has also been suggested that cholesterol may also play a vital role in virulence and contributes to the intrinsic antibiotic resistance of H. pylori40. Besides biofilm formation, the lipid composition of bacterial cells has also been shown to have an impact on antibiotic susceptibility41, probably due to changes in the penetrance of the membrane to antibiotics. Recently, Yonezawa et al.13 reported that H. pylori biofilm formation increases clarithromycin resistance and promotes associated-mutations more frequently than in planktonic cells. Therefore, H. pylori lipid biosynthesis pathways should be explored further to better understand the mechanism of antibiotic resistance and biofilm formation.

Higher abundance of multiple alkaloids, terpenoids, triterpene glycosides and polyphenolic compounds in low biofilm formers spurs our conjecture that these organic compounds may have a role in the initiation of biofilm formation. Alkaloids are synthesized from terpenoid and polyketide. This conjecture is supported by several reports demonstrating that plant and marine compounds with similar structure have anti-biofilm properties42–45. Thus, the potential use of phyto compounds to reduce H. pylori biofilm formation should not be overlooked.

5-Methyl THF, is a biologically active form of folic acid which was found to be increased in high biofilm-formers. In a nutritional complementation experiment by Lebeer et al.46, the introduction of folic acid helped to restore the biofilm-forming ability of luxS knockout mutant of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG which has previously been shown to be defective in biofilm formation. Although eukaryotes are not known to possess the luxS gene, antifolates has also been shown to prevent Cryptococcus biofilm formation and inhibit mature biofilm47. These studies have highlighted the importance of folate metabolism in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic biofilm formation. Therefore, increase of 5-methyl THF in high biofilm-forming H. pylori strains may also demonstrate the importance of folate metabolism in H. pylori biofilm formation.

Currently, most of our understanding of bacterial biofilms comes from studying of biofilms cultured using established in vitro methods. However, there are expected to be significant differences between biofilms grown in the laboratory and in vivo biofilms found in infections. This is the major limitation of this study as the optimized laboratory condition for the culturing of H. pylori biofilm is not representative of the complex and dynamic condition of the human stomach or the environment, which is difficult to fully simulate. Thus, the metabolome of in vitro H. pylori biofilm may be different from that of biofilm found in the stomach or environment. Nevertheless, the findings of this study can form a rational basis for interrogating naturally occurring H. pylori and other bacterial biofilms in naturally occurring tissue and environmental samples.

Conclusion

Biofilm formation in H. pylori at the initial growth stage is complex and is probably driven by its endogenous metabolism. The metabolism of low and high biofilm-forming H. pylori strains is different metabolically. Studying of the underlying metabolic processes that distinguish low and high biofilm-forming H. pylori will enhance our understanding of the possible role of biofilm formation in H. pylori pathogenesis, as well as extragastric survival and transmission of the organism. In addition, these metabolites may be potential anti-biofilm agents against the formation of H. pylori biofilm.

Materials and Methods

Culturing of H. pylori

H. pylori clinical strains used in this study were selected from the collection of the Helicobacter Research Laboratory at the University of Malaya (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia). The biofilm-forming capability of each strain was determined through previous study12,26. Specific biofilm unit is the ratio of the absorbance values of crystal violet stained biofilm normalized against OD600 of the growth of corresponding planktonic bacteria. Specific biofilm unit was taken to be the amount of biofilm formed by the planktonic bacteria. The highest specific biofilm unit was determined for each of the strains. The bacterial strains were cultured on non-selective chocolate blood agar plates supplemented with 7% horse blood (Quad Five, MT, USA). The cultures were incubated at 37 °C for up to 3 days in a humidified 10% CO2 incubator (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA).

Forming of H. pylori biofilm

The 3-day old H. pylori cultures were suspended in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Oxoid, Hampshire, UK) supplemented with 1% β-cyclodextrin (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) and 0.4% yeast extract (Oxoid, Hampshire, UK). An aliquot of 10 ml of bacterial suspension containing 107 CFU/ml of H. pylori was then inoculated into sterile DURAN® borosilicate glass bottle with screw cap (100 ml; Schott, Mainz, Germany) for the development of biofilm. BHI broth without H. pylori served as a negative control. The bottles were incubated in a humidified 10% CO2 incubator and monitored at day 0, 1, 2, and 3 for the presence of biofilm. The screw caps were left loose during incubation to allow for air circulation. Day 1, 2, and 3 cultures of each H. pylori strains were available in independent replicates.

Extraction of metabolites

Biofilm culture was dislodged physically from the wall of the glass bottle and mixed with the planktonic culture before harvesting. As biofilm could readily be observed at the air-medium interface of high biofilm-forming strains cultures, this ensures that both representative low and high biofilm-forming samples were obtained. The bacterial cultures were harvested and washed 3 times at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes at room temperature with BHI broth. The bacterial suspensions were adjusted to OD600 nm of 1.0 in BHI broth and 0.5 ml of bacterial suspensions were used for metabolite extraction. Bacterial pellets were processed according to the modified Bligh and Dyer extraction method48. In brief, 300 µl methanol-chloroform (2:1, v/v) was added to each bacterial pellet and vortexed for 1 minute followed by incubation for 1 hour at room temperature. Following which, 100 µl of chloroform and 100 µl of water were added to induce phase separation. The extract was left standing for 10 minutes at room temperature. The mixture was then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4 °C. The upper aqueous and lower organic phases were collected and dried in Labconco Refrigerated Centrivap concentrator (Kansas City, MO, USA) at 4 °C. The dried samples were subsequently dissolved in 50 μl of acetonitrile/water (95:5, v/v) and pooled together for LC/MS analysis.

LC/MS profiling of metabolites

Mass spectrometric analysis of the samples was performed on a 1260 Infinity Quaternary Liquid Chromatography system equipped with a 6540 Quadrupole Time-of-Flight mass spectrometer attached to a Dual Agilent Jet Stream Electrospray Ionization (Dual AJS ESI) ionization source (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). Agilent MassHunter LC/MS Data Acquisition software (version B.05.01) was used for instrumental control and data collection. The samples were separated using the Agilent Zorbax Eclipse plus C18 Rapid Resolution High Throughput separation column (2.1 × 100 mm 1.8 μm) and analyzed in both positive and negative modes. In order to obtain a broad coverage of the metabolome, ionization was performed in both positive and negative modes. In the positive mode, the mobile phases used were water with 1% formic acid (A) and acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid (B). In negative mode, the mobile phases were water with 1 mM ammonium fluoride and 0.1% formic acid (A) and acetonitrile (B). For both modes, a linear gradient was set to run from 2% to 98% B over 25 minutes, at 0.5 ml/min. In the event of the run, the injection volume was set at 3 μl with three injections were made for each sample. A typical sample ESI condition was set at voltage 3.0 kV, gas temperature 300 °C, drying gas 8 L/min, nebulizer 35 psig, VCap 3500 V, fragmentor 175 V and skimmer 65 V. The instrument was set to acquire over the m/z range of 100–1700 with an acquisition rate of 1 spectra/s. For positive ionization mode, two reference masses of (i) 121.0509 m/z and (ii) 922.0098 m/z were measured continuously while for negative ionization mode, the reference masses were (i) 112.9855 and (ii) 1033.9881.

Data analysis and statistics

A two-pass feature extraction process was used to find molecular features from complex accurate mass data. Raw data was deconvoluted into individual chemical peaks by the MassHunter Qualitative Analysis software (Qual; version R.06.00) (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) for Molecular Feature Extraction (MFE), a naïve or “untargeted” data-mining algorithm, which finds groups of co-variant ions for each unique feature in a chromatogram. Features with a minimum absolute abundance of 1000 counts within a defined mass accuracy (+/−5 ppm) were chosen. The data generated were subsequently imported into the MPP software (version B.12.61) for binning, aligning, and creating a consensus for each feature. The second pass used the list of consensus features and the “Find by Molecular Formula” algorithm in Qual for “targeted” feature re-extraction. This two-pass feature extraction approach improved the quality and accuracy of mass, retention time and abundance values for each candidate feature compared with the MFE only data mining. Finally, the data were imported into MPP again for annotation and statistical analysis. Using the baselining option of MPP, the abundance for each feature was normalized to the median abundance across all of the samples. Unsupervised principal component analysis (PCA) was performed with median centering and scaling to display the inherent variance between low and high biofilm-forming groups at different age of cultures. Statistical evaluation of the data was performed using one-way ANOVA. A cutoff value of p < 0.005 was considered statistically significant in one-way ANOVA, using the Benjamini and Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) set to <1% for multiple testing corrections. Identification of the metabolites was done through the IDBrowser function of MPP by matching mined features based on accurate mass, isotope ratios, abundances and spacing against metabolites in the AM-PCDL database (version 5.0). Further statistical testing was carried out using the IBM SPSS Statistics (version 22) software.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Kim Hardie (University of Nottingham, UK) for kindly providing the H. pylori J99ΔluxS strain and Dr. Lee Woon Ching (formerly from University of Malaya) for the J99ΔcagY strain. This study was funded by the University of Malaya-Ministry of Education (UM-MoE) High Impact Research (HIR) Grant UM.C/625/1/HIR/MoE/CHAN/13/3 (Account No. H-50001-A000030) and the National Medical Research Council (NMRC) Grant No. R-182-000-180-213. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

The project was conceived by C.G.N. and M.F.L. Experimental studies were designed by C.G.N., K.L.G., J.V., B.H. and M.F.L. Biofilm experiments were performed by E.H.J.W. and C.G.N. Metabolomics experiments were performed by E.H.J.W. and C.G.N. E.H.J.W., C.G.N. and B.H. wrote the paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Jamuna Vadivelu and Mun Fai Loke contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-19697-0.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jamuna Vadivelu, Email: jamuna@ummc.edu.my.

Mun Fai Loke, Email: lmunfai@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Carpentier B, Cerf O. Biofilms and their consequences, with particular reference to hygiene in the food industry. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1993;75:499–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1993.tb01587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costerton JW, Lewandowski Z, Caldwell DE, Korber DR, Lappin-Scott HM. Microbial biofilms. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1995;49:711–745. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.003431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;284:1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stanley NR, Lazazzera BA. Environmental signals and regulatory pathways that influence biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;52:917–924. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kusters JG, van Vliet AH, Kuipers EJ. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Microbial Rev. 2006;19:4449–4490. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00054-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Attaran B, Falsafi T, Moghaddam AN. Study of biofilm formation in C57Bl/6J mice by clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2016;22:161–168. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.178529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carron MA, Tran VR, Sugawa C, Coticchia JM. Identification of Helicobacter pylori biofilms in human gastric mucosa. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2016;10:712–717. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cellini L, et al. Characterization of an Helicobacter pylori environmental strain. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008;105:761–769. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cole SP, Harwood J, Lee R, She R, Guiney DG. Characterization of monospecies biofilm formation by Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:3124–3132. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.10.3124-3132.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coticchia JM, et al. Presence and density of Helicobacter pylori biofilms in human gastric mucosa in patients with peptic ulcer disease. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2006;10:883–889. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stark RM, et al. Biofilm formation by Helicobacter pylori. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1999;28:121–126. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ng CG, Loke MF, Goh KL, Vadivelu J, Ho B. Biofilm formation enhances Helicobacter pylori survivability in vegetables. Food Microbiology. 2017;62:68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yonezawa, H. et al. Impact of Helicobacter pylori biofilm formation on clarithromycin susceptibility and generation of resistance mutations. PLoS One8, 10.1371/journal.pone.0073301 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Yonezawa, H., Osaki, T. & Kamiya, S. Biofilm formation by Helicobacter pylori and its involvement for antibiotic resistance. BioMed. Res. Int9, 10.1155/2015/914791 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Servetas SL, et al. Characterization of key Helicobacter pylori regulators identifies a role for ArsRS in biofilm formation. J. Bateriol. 2016;198:2536–2548. doi: 10.1128/JB.00324-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shao C, et al. Changes of proteome components of Helicobacter pylori biofilms induced by serum starvation. Mol. Med. Rep. 2013;8:1761–1766. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beale DJ, et al. Application of metabolomics to understanding biofilms in water distribution systems: a pilot study. Biofouling. 2013;29:283–294. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2013.772140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rochfort S. Metabolomics reviewed: a new “omics” platform technology for systems biology and implications for natural products research. J. Nat. Prod. 2005;68:1813–1820. doi: 10.1021/np050255w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chandramouli KH, Dash S, Zhang Y, Ravasi T, Qian PY. Proteomic and metabolomic profiles of marine Vibrio sp 010 in response to an antifoulant challenge. Biofouling. 2013;29:789–802. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2013.805209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chavez-Dozal A, Gorman C, Nishiguchi MK. Proteomic and metabolomic profiles demonstrate variation among free-living and symbiotic Vibrio fischeri biofilms. BMC Microbial. 2015;15:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12866-014-0320-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kouremenos KA, Beale DJ, Antti H, Palombo EA. Liquid chromatography time of flight mass spectrometry based environmental metabolomics for the analysis of Pseudomonas putida bacteria in potable water. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2014;966:179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2014.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stipetic LH, et al. A novel metabolomic approach used for the comparison of Staphylococcus aureus planktonic cells and biofilm samples. Metabolomics. 2016;12:75. doi: 10.1007/s11306-016-1002-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeom, J., Shin, J. H., Yang, J. Y., Kim, J. & Hwang, G. S. 1H NMR-based metabolite profiling of planktonic and biofilm cells in Acinetobacter baumannii 1656-2. PLoS One8, 10.1371/journal.pone.0057730 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Wong HS, Maker GL, Trengove RD, O’Handley RM. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry-based metabolite profiling of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium differentiates between biofilm and planktonic phenotypes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015;81:2660–2666. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03658-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Booth SC, et al. Differences in metabolism between the biofilm and planktonic response to metal stress. J. Proteome. Res. 2011;10:3190–3199. doi: 10.1021/pr2002353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong, E. H. J. et al. Comparative genomics revealed multiple Helicobacter pylori genes associated with biofilm formation in vitro. PLoS One11, 10.1371/journal.pone.0166835 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.McGarigal, K., Cushman, S. A. & Stafford S. Multivariate Statistics for Wildlife and Ecology Research. New York: Springer-Verlag (2000).

- 28.Cukkemane N, et al. Anti-adherence and bactericidal activity of sphingolipids against Streptococcus mutans. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2015;123:221–227. doi: 10.1111/eos.12200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang LH, et al. A bacterial cell-cell communication signal with cross-kingdom structural analogues. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;51:903–912. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barber CE, et al. A novel regulatory system required for pathogenicity of Xanthomonas campestris is mediated by a small diffusible signal molecule. Mol. Microbiol. 1997;24:555–566. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3721736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davies DG, Marques CN. A fatty acid messenger is responsible for inducing dispersion in microbial biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 1997;1191:1393–1403. doi: 10.1128/JB.01214-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marques CN, Morozov A, Planzos P, Zelaya HM. The fatty acid signaling molecule cis-2-decenoic acid increases metabolic activity and reverts persister cells to an antimicrobial-susceptible state. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;80:6876–6991. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01576-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang J-L, et al. Genetic and molecular analysis of a cluster of rpf genes involved in positive regulation of synthesis of extracellular enzymes and polysaccharide in Xanthomonas campestris pathovar campestris. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1991;226:409–417. doi: 10.1007/BF00260653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koeberle A, Pollastro F, Northoff H, Werz O. Myrtucommulone, a natural acylphloroglucinol, inhibits microsomal prostaglandin E(2) synthase-1. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009;156:952–961. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00070.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quraishi O, Mancini JA, Riendeau D. Inhibition of inducible prostaglandin E(2) synthase by 15-deoxy-Delta(12,14)-prostaglandin J(2) and polyunsaturated fatty acids. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002;63:1183–1189. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(02)00844-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alem MA, Douglas LJ. Prostaglandin production during growth of Candida albicans biofilms. J. Med. Microbiol. 2005;54:1001–1005. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mishra A, et al. Imaging pericytes and capillary diameter in brain slices and isolated retinae. Nat. Protocols. 2014;9:323–336. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abdelmegeed E, Shaaban MI. Cyclooxygenase inhibitors reduce biofilm formation and yeast-hypha conversion of fluconazole resistant Candida albicans. J. Microbiol. 2013;51:598–604. doi: 10.1007/s12275-013-3052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Asadishad BHG, Prostaglandin TufenkjiN. production during growth of Candida albicans biofilms. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2012;334:87–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGee DJ, et al. Cholesterol enhances Helicobacter pylori resistance to antibiotics and LL-37. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 2011;55:2897–2904. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00016-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hewelt-Belka W, et al. Untargeted lipidomics reveals differences in the lipid pattern among clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus resistant and sensitive to antibiotics. J Proteome Res. 2016;15:914–922. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.da Silva Negreiros Neto T, et al. Activity of pyrrolizidine alkaloids against biofilm formation and Trichomonas vaginalis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016;83:323–329. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hodnik Z, et al. Inhibition of biofilm formation by conformationally constrained indole-based analogues of the marine alkaloid oroidin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;24:2530–2534. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.03.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li X, et al. Effects of total alkaloids of Sophora alopecuroides on biofilm formation in Staphylococcus epidermidis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/4020715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mon HH, et al. Serrulatane Diterpenoid from Eremophila neglecta exhibits bacterial biofilm dispersion and inhibits release of pro-inflammatory cytokines from activated macrophages. J. Nat. Prod. 2015;78:3031–3040. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lebeer S, Verhoeven TLA, Perea Vélez M, Vanderleyden J, De Keersmaecker SCJ. Impact of environmental and genetic factors on biofilm formation by the probiotic strain Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:6768–6775. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01393-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Aguiar Cordeiro R, et al. Antifolates inhibit Cryptococcus biofilms and enhance susceptibility of planktonic cells to amphotericin B. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013;32:557–564. doi: 10.1007/s10096-012-1774-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bligh ELG, Dyer WJA. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/y59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.