Abstract

Topoisomerases are important targets for antibacterial and anticancer therapies. Bacterial topoisomerase I remains to be exploited for antibiotics that can be used in the clinic. Inhibitors of bacterial topoisomerase I may provide leads for novel antibacterial drugs against pathogens resistant to current antibiotics. TB is the leading infectious cause of death worldwide, and new TB drugs against an alternative target are urgently needed to overcome multi-drug resistance. Mycobacterium tuberculosis topoisomerase I (MtbTopI) has been validated genetically and chemically as a TB drug target. Here we conducted in silico screening targeting an active site pocket of MtbTopI. The top hits were assayed for inhibition of MtbTopI activity. The shared structural motif found in the active hits was utilized in a second round of in silico screening and in vitro assays, yielding selective inhibitors of MtbTopI with IC50s as low as 2 µM. Growth inhibition of Mycobacterium smegmatis by these compounds in combination with an efflux pump inhibitor was diminished by the overexpression of recombinant MtbTopI. This work demonstrates that in silico screening can be utilized to discover new bacterial topoisomerase I inhibitors, and identifies a novel structural motif which could be explored further for finding selective bacterial topoisomerase I inhibitors.

Introduction

Antibiotic resistance is a dire problem that is facing the global community. The emergence of drug-resistant strains of pathogenic bacteria is rendering our current antibiotics almost powerless in certain cases1,2, and this has grave implications for the future of public health. We are facing a “post-antibiotic era”3: a time where previously treatable infections, including those that may be acquired during surgeries, can become life threatening. Pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the pathogen responsible for 1.7 million deaths in 2016 alone4 have evolved, leaving us with multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) and in some cases even extensively-drug resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB)5, strains that are not responsive to many of the currently available therapies. If we are to battle the threat that is antibiotic resistance, we need novel drugs and drug targets.

Topoisomerase I is one such novel drug target that has not yet been targeted by existing antibiotic drugs6,7. Topoisomerases are ubiquitous enzymes that are responsible for maintaining the optimal supercoiling level of DNA inside the cell. They are important in cellular processes such as DNA replication, transcription, and repair, and maintenance of genome integrity. Bacterial topoisomerase I (TopI), a type IA topoisomerase, is specifically responsible for relaxing DNA that is negatively supercoiled. Its active-site tyrosine residue attacks the phosphodiester backbone of unwound single-stranded DNA. The enzyme thus forms a covalent phosphotyrosine bond, and creates a break in the DNA. TopI will then relax the DNA by passing the unbound strand through the break, and then sealing the nick. The DNA is released from the topoisomerase, now in a more relaxed state8–10. Type IA topoisomerase activity is essential for resolving topological barriers that require passage of DNA through single-strand breaks, and as such, if the topoisomerase’s activity is compromised it can lead to cell growth arrest and even cell death7,11,12. M. tuberculosis topoisomerase I is the only type IA topoisomerase present in the cell, and is essential for viability13,14. Loss of TopI activity in M. tuberculosis leads to cell death. For these reasons, bacterial topoisomerase I is a promising new drug target, especially in mycobacteria.

When it comes to drug discovery, there are many valid approaches including virtual docking, high-throughput screening, and fragment-based screening, among others15,16. Many of these drug discovery approaches have been used successfully to find novel structures for inhibiting specific targets. One area that has become more popular through the application of high performance computing is the use of in silico docking. In the docking studies, a crystal structure or homology model of the desired target is screened against a large compound library, usually hundreds of thousands of compounds17. The compounds are scored on their ability to interact with specific pockets on the target enzyme. Many programs are available to carry out docking studies, and combined with molecular dynamics, this method can be a powerful tool.

In these studies, bacterial topoisomerase I was the intended drug target. In this screen, the crystal structure 5D5H18 for M. tuberculosis TopI (MtbTopI) was used. This crystal structure is a truncated form of the protein (missing the last 230 residues at the C-terminal end) that retains the ability to cut and rejoin single-stranded DNA. The Elite library from Asinex was used to screen the active site region on the enzyme expected to be the DNA binding site. The compound library was first screened against the original structure, and then the top 1,000 hits from that screen were docked against molecular dynamics-generated crystal structure poses. The top hits from the virtual screen were purchased and tested in the lab. From among the most potent inhibitors, there was a shared structural motif. This discovery of a common moiety was used to fuel a second round of virtual screens, this time with available Chembridge compounds that contained the motif of interest. The in vitro assays results confirmed virtual screening as a worthwhile method of discovering novel bacterial topoisomerase I inhibitors, and identified a novel structural motif as a potential pharmacophore for the inhibition of MtbTopI.

Results

Virtual screening of Asinex Elite Library

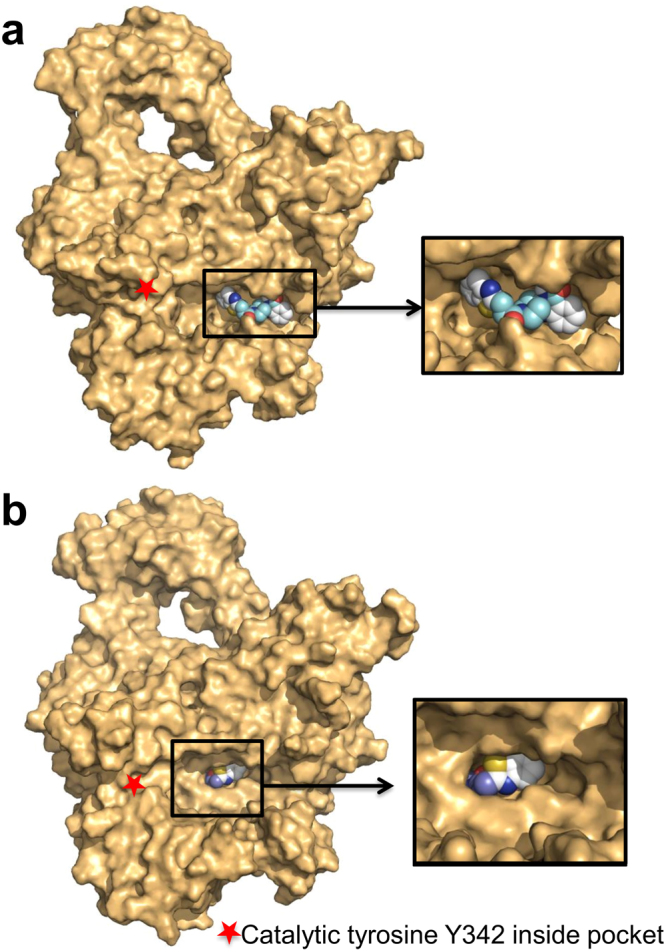

Two screenings were carried out sequentially; the first docked the Asinex elite library of 104,000 compounds against the crystal structure 5D5H18, and the second docked the top 1,000 hits from the first screen against 1,000 molecular-dynamics-generated structures of 5D5H. The MD-generated structures opened the DNA-binding pocket and allowed the compounds to bind much deeper inside the pocket, as opposed to binding closer to the surface on the 5D5H crystal structure (Fig. 1). The output was used to compile a list of the top binding compounds. All of the hits were scanned using the FAF-Drugs3 program19 to filter out pan-assay-interference compounds (PAINS), compounds that tend to interfere with screening by non-specific interactions, thus giving “positive” results in assays of all kinds20. Thus ensuring none of the hits were PAINS compounds, the top 82 compounds were purchased to be tested in the lab.

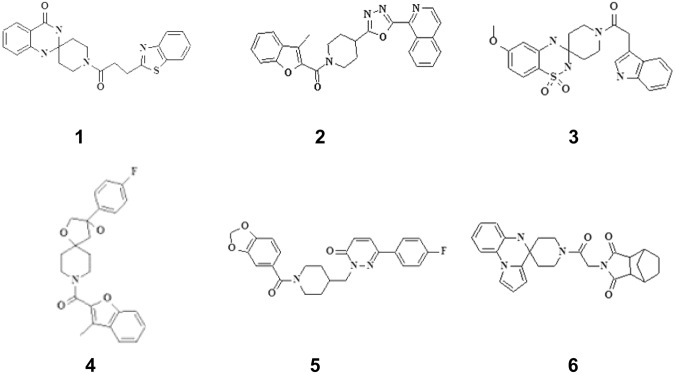

Figure 1.

Molecular dynamics studies opened the DNA-binding pocket on MtbTopI. The Asinex compounds bind closer to the surface on the 5D5H crystal structure (a), while they can bind deeper inside the pocket on some of the MD-generated structures (b). Shown is Compound 1.

Top candidates from screening of Asinex library

The 82 purchased Asinex compounds were tested for inhibition of the relaxation activity of MtbTopI. Six compounds were found to inhibit MtbTopI with IC50 ≤ 500 µM (Table 1). Compound 1 (SYN 12502158) with an IC50 of 15.6 µM, was the most potent inhibitor against MtbTopI, with 4-fold or more selectivity for the type IA bacterial topoisomerase I versus the type IB human topoisomerase I. Compounds 2–4 had IC50 values ranging from 62.5 µM to 125 µM, and did not inhibit human topoisomerase I when tested at 250 µM.

Table 1.

IC50 values of Asinex hit compounds against MtbTopI and human topoisomerase I (hTOPI).

| Compound Number | Asinex ID | MtbTopI Relaxation Inhibition (IC 50 , µM) | hTOPI Relaxation Inhibition (IC 50 , µM) | Selectivity Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SYN 12502158 | 15.6 | 93.75 | 6 |

| 2 | AOP 19767246 | 62.5 | >250 | >4 |

| 3 | ADD 15417014 | 62.5 | >250 | >4 |

| 4 | ADM 12439418 | 125 | >250 | >2 |

| 5 | LEG 11118762 | 250 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 6 | AEM 11113320 | 500 | n.d. | n.d. |

n.d. – not determined.

Selectivity Score = hTOPI IC50/MtbTopI IC50.

Follow-up virtual screening

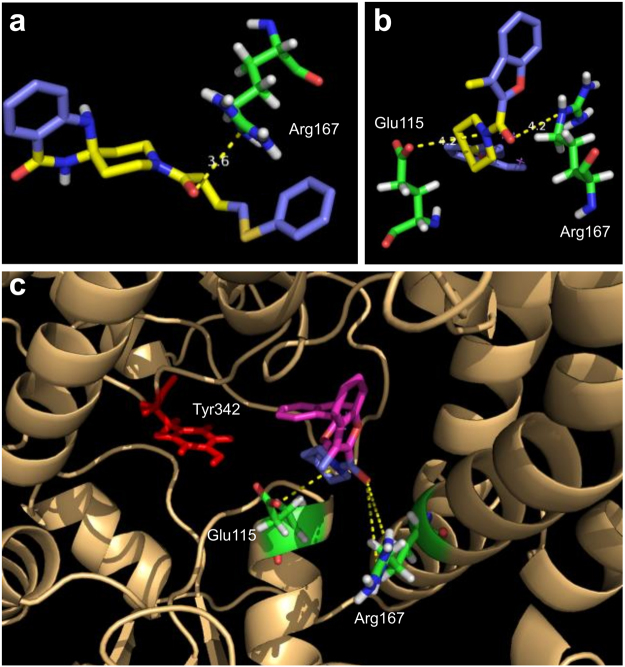

Although the first screen was successful at finding some MtbTopI inhibitors, there is a need to improve the potency of inhibition. Interestingly, the Asinex compounds identified contained a common structural motif—a piperidine amide located in the center of the molecule, with different groups on either side (Fig. 2). After noting this similarity, we examined the docking positions in the MD-generated structures for these top compounds to elucidate the action of this common motif. In the top docking positions, the motif appears to be interacting with key residues strictly conserved for catalysis, Arg167 and Glu11521,22. These residues are located in the DNA-binding pocket on the MtbTopI. The corresponding residues in Escherichia coli topoisomerase I can be observed to be interacting with the ribose ring of the DNA substrate in the structure of its covalent complex22. Specifically, the amide oxygen in the common motif interacts with Arg167, while the amide nitrogen interacts with Glu115 (Fig. 3). This structural motif may be acting as a so-called “lynchpin” to hold the compound in place at the enzyme active site. This binding behavior could explain the observed enzyme inhibition.

Figure 2.

Structures of Asinex compounds identified from in silico screening and in vitro MtbTopI assay.

Figure 3.

Tertiary amide moiety on Asinex hits interacts with key residues. The common piperidine amide moiety on the Asinex hits shows interactions with Arg167 and Glu115. Shown are (a) Compound 1 with Arg167, (b) Compound 2 with both Arg167 and Glu115, and (c) the compound’s binding position (shown is compound 2) is located near catalytic tyrosine 342.

To further identify inhibitors of MtbTopI related to this piperidine amide motif, a search was conducted to find compounds in the Chembridge library that contained a cyclic tertiary amide motif. Over 200 compounds were found to contain such amide substructure, and they were docked with the same procedures as the Asinex compounds. The 96 compounds with the top docking scores were purchased from Chembridge for further testing.

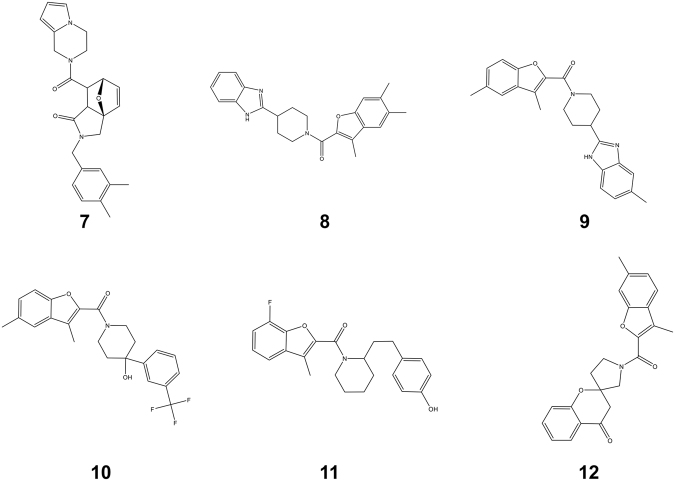

Top candidates from Chembridge screen inhibit bacterial topoisomerase I selectively

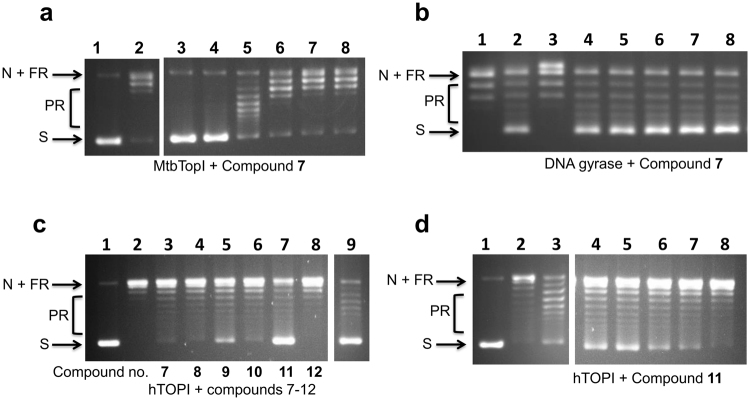

The 96 compounds purchased from Chembridge were tested in vitro against purified MtbTopI to ascertain their ability to inhibit enzymatic relaxation activity. Eighteen compounds were found to have IC50 ≤ 125 µM (Table 2). The structures of the six compounds with IC50 ≤ 62.5 µM (Compounds 7–12) are shown in Fig. 4. Compound 7 (Chembridge ID 49981944) had an IC50 of 2 µM (Fig. 5a), significantly lower than the other compounds tested. Compound 7 was also tested against E. coli DNA gyrase, a bacterial type IIA topoisomerase, and no inhibition was seen at up to 500 µM, confirming the selectivity of the inhibition for type IA topoisomerase activity (Fig. 5b). Compounds 7–12 (Fig. 4) were also assayed against the human topoisomerase I and E. coli DNA gyrase to determine whether they are selective for type IA bacterial topoisomerase. The results showed none had IC50 < 250 µM for inhibition of human topoisomerase I and <500 µM for DNA gyrase (Fig. 5c,d). Gel electrophoresis of the MtbTopI and human topoisomerase I relaxation reaction products in the presence of ethidium bromide showed that the compounds did not increase the formation of nicked DNA, while camptothecin increased nicking of DNA by human topoisomerase I significantly (Supplementary Fig. S1). Assays against E. coli topoisomerase I (Supplementary Fig. S2) showed that Compounds 7, 8, 9 also inhibited the relaxation activity of this bacterial topoisomerase I, with Compound 7 (IC50 15.6–31.3 µM) the strongest inhibitor among the three compounds tested, but with less potency than the inhibition of MtbTopI.

Table 2.

IC50 values of Chembridge hit compounds against MtbTopI, human topoisomerase I (hTOPI) and E. coli DNA gyrase.

| Compound Number | Chembridge ID | MtbTopI Relaxation Inhibition (IC 50 , µM) | hTOPI Relaxation Inhibition (IC 50 , µM) | E. coli DNA Gyrase Supercoiling Inhibition (IC 50 , µM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 49981944 | 2 | >500 | >500 |

| 8 | 9302190 | 62.5 | >500 | >500 |

| 9 | 37097280 | 62.5 | >500 | >500 |

| 10 | 88421238 | 62.5 | >500 | >500 |

| 11 | 73600812 | 62.5 | 250 | >500 |

| 12 | 80760557 | 62.5 | >500 | >500 |

| 13 | 17951480 | 62.5–125 | >500 | n.d. |

| 14 | 15044152 | 62.5–125 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 15 | 7931615 | 62.5–125 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 16 | 7875243 | 125 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 17 | 19138872 | 125 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 18 | 19046220 | 125 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 19 | 67687224 | 125 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 20 | 18538504 | 125 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 21 | 68171804 | 125 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 22 | 44982805 | 125 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 23 | 67941389 | 125 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 24 | 63920724 | 125 | n.d. | n.d. |

n.d. – not determined.

Figure 4.

Structures of Chembridge compounds 7–12 with IC50 ≤ 62.5 µM.

Figure 5.

Selective inhibition of MtbTopI by Chembridge hit compounds. (a) Inhibition of MtbTopI relaxation activity by Compound 7. Lane 1: negatively supercoiled plasmid DNA substrate; Lane 2: DMSO as negative control; Lanes 3–8: 8, 4, 2, 1, 0.5 and 0.25 µM Compound 7. The lanes shown are from the same gel. (b) Compound 7 does not inhibit E. coli DNA gyrase supercoiling activity. Lane 1: relaxed covalently closed circular DNA; Lane 2: DMSO as negative control; Lane 3: 150 µM ciprofloxacin; Lanes 4–8: 500, 250, 125, 62.5, and 31.3 µM Compound 7. (c) Assay of Chembridge top hits for inhibition of human topoisomerase I relaxation activity. Lane 1: negatively supercoiled plasmid DNA; Lane 2: DMSO as negative control; Lanes 3–8: Compounds 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12 respectively, at 500 µM; Lane 9: 200 µM camptothecin. Lanes 1–9 shown here are from the same gel. (d) Inhibition of human topoisomerase I relaxation activity by Compound 11. Lane 1: negatively supercoiled plasmid DNA substrate; Lane 2: DMSO as negative control; Lane 3: 200 µM camptothecin; Lanes 4–8: 500, 250, 125, 62.5, and 31.3 µM Compound 11. The lanes shown here are from the same gel. S: Supercoiled DNA, N: Nicked DNA, FR: Fully Relaxed DNA, PR: Partially relaxed DNA.

Antibacterial assay against M. smegmatis

The non-pathogenic M. smegmatis was used in antibacterial assays to assess whether the identified MtbTopI inhibitors can inhibit the growth of mycobacteria. If inhibition of topoisomerase I catalytic activity is part of the antibacterial mode of action, the MIC should increase if recombinant MtbTopI is overexpressed23 (M+ strain with plasmid pTA-M+ versus the control strain Mnol with cloning vector). The overexpression of MtbTopI does not affect the general cell viability23. MtbTopI expression levels also do not affect the MIC of antibiotics that do not target the enzyme—ciprofloxacin MIC levels are the same in both strains. Either weak or no antibacterial activity was observed in the initial antibacterial assays, so the MIC measurement was repeated in the presence of the efflux pump inhibitor thioridazine24,25. The antibacterial activity for many of the compounds was enhanced by the presence of the efflux pump inhibitor. The results (Table 3) showed that the MICs for these compounds are shifted higher with the overexpression of recombinant MtbTopI, suggesting that inhibition of topoisomerase I activity contributes to the antibacterial activity. The barrier for penetrance through the mycobacterial cell wall may be the reason for lack of direct correlation between MIC and IC50 values.

Table 3.

MIC values for antibacterial activity of identified MtbTopI inhibitors against M.

| Compound Number | MnoI Growth Inhibition (MIC, µM) | M+ Growth Inhibition (MIC, µM) | MnoI Growth Inhibition with TZ (MIC, µM) | M+ Growth Inhibition with TZ (MIC, µM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 |

| 2 | 187.5 | >250 | 31.3 | 62.5 |

| 3 | 250 | >250 | 31.3 | 62.5 |

| 7 | >500 | >500 | 500 | >500 |

| 8 | >500 | >500 | 23.4 | 31.3 |

| 9 | 125 | >500 | 23.4 | 31.3 |

| 10 | 125 | >500 | 23.4 | 46.9 |

| 11 | 500 | >500 | 46.9 | 125 |

| 12 | >500 | >500 | 500 | >500 |

smegmatis transformed with cloning vector (MnoI strain) or clone overexpressing recombinant MtbTopI (M+ strain). The efflux pump inhibitor thioridazine (TZ) at 6.25 µg/ml was included in some of the assays.

Discussion

Multi-drug resistant TB is a serious global health challenge because of the difficulty presented for clinical treatment. There is an urgent need for new TB drugs, preferably via a novel mechanism. MtbTopI has been validated genetically and chemically to be a useful new target for TB drug discovery. MtbTopI inhibitors that can inhibit the growth of M. tuberculosis have been described23,26, but have not advanced into candidates for clinical drug development. A group of the previously described MtbTopI inhibitors was discovered by docking studies utilizing a modeled structure of MtbTopI26,27. With the availability of the MtbTopI crystal structure that contains the active site for DNA cleavage and rejoining, there is potential for further utilizing in silico screening to aid in the discovery of novel molecular scaffolds as MtbTopI inhibitors.

In this study, an active site pocket in the DNA-binding region between domains D1 and D4 of MtbTopI was targeted for in silico screening with the Autodock program. Molecular dynamics was used to further open the DNA-binding pocket and allow the compounds to have interactions much deeper inside the pocket. Initial docking against the Asinex Elite library identified a set of compounds with a common piperidine amide motif not found in previously characterized MtbTopI inhibitors. Examination of the docking outputs showed that the sterically rigid amide moiety may be interacting with specific Arg and Glu side chains that are strictly conserved in type IA bacterial topoisomerase I for interactions with the DNA backbone. Future structural studies of enzyme-compound co-crystal or analysis of resistant mutants selected against more potent derivatives are needed to verify the compound binding position.

When the in silico screening was repeated on Chembridge compounds containing a tertiary cyclic amide in their structures, a high percentage of the purchased hits were found to inhibit the relaxation activity of MtbTopI. Selectivity was maintained as confirmed by the lack of effect on type IB human topoisomerase I relaxation activity and type IIA gyrase supercoiling activity.

An MtbTopI inhibitor with an IC50 of 2 µM (Compound 7) was identified among the hits from the Chembridge compounds. However, this and the other similar MtbTopI inhibitors did not show strong antibacterial activity when assayed against M. smegmatis. The antibacterial activity improved with the addition of an efflux pump inhibitor. The observed antibacterial activities were sensitive to the level of topoisomerase I activity in the cell. The MIC values were shifted higher with the overexpression of recombinant MtbTopI, in support of inhibition of topoisomerase I activity being at least contributing to the antibacterial mode of action.

Experimental evaluation of a set of 80 compounds with variable R group substitutions at three positions of a common polyamine scaffold in a previous study23 has identified small molecule inhibitors with greater potency for inhibition of MtbTopI and anti-mycobacterial activities. Future studies combining synthesis and assays of a large set of new compounds with different backbones plus substitutions can further explore the piperidine amide or cyclic tertiary amide moiety as a pharmacophore for inhibition of MtbTopI. Attempts can be made to modify this pharmacophore for improving the compound penetrance into mycobacteria, as well as enhancing the potency of inhibition. Exploration of other pockets in the MtbTopI structure by in silico screening may identify additional molecular scaffolds that are useful for developing specific MtbTopI inhibitors for potential clinical application as TB drugs.

Methods

In silico docking studies

The Asinex Elite library (http://www.asinex.com), containing just over 100,000 compounds, was screened against the crystal structure of MtbTopI truncated after the first 704 residues (pdb: 5D5H) using the AutoDock Vina 1.1.2. program28. The DNA-binding region in the active site was selected as the target for the screening. The compound structure files were first converted to pdbqt format, with 3-dimensional structure and added polar hydrogen atoms, using Open Babel29. The compounds were first screened and the resulting scores were sorted and ranked using custom scripts. The top 1,000 compounds were then selected for screening against multiple conformations of the binding site generated with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations described below. From the simulation trajectory, 1,000 conformations were selected and with 1,000 top compounds, this resulted in 1,000,000 docking runs. The scores were then sorted and the compounds were ranked according to their binding affinities.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation

To incorporate the inherent flexibility of MtbTopI, protein conformations were generated with a 50-ns all-atom MD simulation for pdb 5D5H in explicit solvent. The system was set up using the Charmm-Gui web interface30. The protein was solvated with TIP3 water in cubic box and neutralized with counter ions. The solvated system (protein, water and the neutralizing ions) contained ~182,000 atoms. All-atom molecular dynamics simulations were performed with the CHARMM36 force field31 using NAMD 2.1132. The particle mesh Ewald (PME) method33 was used to calculate the long-range ionic interactions. The covalent bonds involving hydrogen atoms were constrained by SHAKE34. For each system, a 10,000-step minimization followed by 100 ps equilibration runs were performed using 1 fs time step. This was followed by the NPT (constant pressure/temperature) production runs at 300 K using 2 fs time steps for 50 ns. The pressure was controlled using the Nose-Hoover Langevin-piston method35, with a piston period of 50 fs and a decay of 25 fs. Similarly, the temperature was controlled using the Langevin temperature coupling with a friction coefficient of 1 ps−1. Visualization of the trajectories and extraction of pdb frames were done with VMD36.

Mtb topoisomerase I relaxation inhibition

The relaxation inhibition assays were carried out in a buffer containing 40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, and 20 mM NaCl, as described by Godbole et al.26. Briefly, 25 ng of M. tuberculosis topoisomerase I purified in the lab according to previous protocols37 was added to the reaction buffer to achieve I U/reaction mixture. The enzyme mixture was aliquoted into 10 µL before the addition of 0.5 µL of the compound of interest at various concentrations dissolved in DMSO. The mixtures were then incubated for 15 minutes at 37 °C before adding 150 ng of CsCl-gradient purified pBAD/Thio plasmid DNA in the same buffer for a final volume of 20 µL and enzyme concentration of 12.5 nM. The mixtures were further incubated at 37 °C for 30 minutes to allow for the enzyme’s relaxation activity. The reactions were stopped by the addition of 4 µL of a buffer containing 5% SDS, 0.25% bromophenol blue, and 25% glycerol. The samples were then run on a 1% agarose gel overnight at 25 V before ethidium bromide staining. IC50 was defined as the concentration of compound that resulted in 50% of the input DNA substrate remaining as supercoiled DNA in the relaxation assay. The same IC50s were observed when the experiments were replicated three times.

Human topoisomerase I relaxation inhibition

Human topoisomerase I assays were carried out in a buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% BSA, 0.1 mM spermidine, and 5% glycerol. The enzyme (from TopoGen) was diluted in the above buffer and aliquoted into 10 µL samples such that 0.5U was present in each. 0.5 µL of compound at various concentrations was added before the addition of 150 ng of purified pBAD/Thio purified plasmid DNA for a final volume of 20 µL. The samples were incubated for 30 minutes at 37 °C before stopping by the addition of 4 µL of buffer containing 5% SDS, 0.25% bromophenol blue, and 25% glycerol. The samples were analyzed by gel electrophoresis as previously described23,38,39. The experiments were replicated twice.

DNA gyrase supercoiling inhibition assay

E. coli DNA gyrase was obtained from New England BioLabs. Two units of the enzyme were added to a reaction buffer provided by the manufacturer (35 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 4 mM MgCl2, 24 mM KCl, 2 mM DTT, 1.75 mM ATP, 5 mM spermidine, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, and 6.5% glycerol). 0.5 µL of the compounds dissolved in DMSO or the solvent alone were added to the enzyme mixture. 300 ng of relaxed covalently closed plasmid DNA was then added for a final volume of 20 µL. The reactions were incubated for 30 minutes at 37 °C before termination by the addition of 4 µL of the SDS stop buffer. The samples were then loaded into a 1% agarose gel and run at 25 V overnight39. The experiments were replicated twice.

Mycobacterium smegmatis MIC determination

Strains used include the wild type M. smegmatis mc2155 as well its transformants containing an overexpression plasmid pTA-M+, which overexpresses MtbTopI, or the control vector pKW-noI described previously23. Cells were prepared by growing overnight at 37 °C in 7H9 media supplemented with 0.2% glycerol, 0.05% Tween 80, and 10% albumin, dextrose, sodium chloride (ADN). Overexpression strains were grown in the presence of 50 µg/ml hygromycin as well. The cells were grown to saturation and then diluted 1:100 in 7H9 without ADN supplementation. After another overnight growth to saturation, the cells were adjusted to OD600 = 0.1 and diluted 1:5 in 7H9 media. Aliquots of 50 µL of the diluted cells (corresponding to ~106 CFU) were then added to a clear-bottom 96-well plate that contained 50 µL of the serially diluted compound in the same media. The plate was incubated for 48 hours with shaking at 37 °C, and the optical density was measured approximately every 4 hours. The minimum inhibitory concentration is recorded as the concentration that prevented at least 90% growth when compared to the control wells. For some of the compounds, the MIC measurements were also carried out in the presence of the efflux pump inhibitor thioridazine (from Sigma Aldrich) at 6.25 µg/ml (half the MIC for growth inhibition by thioridazine alone). The experiments were replicated three times.

Data availability

All the relevant data are available upon request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by R01 AI069313 from the National Institutes of Health (to Y.T.). S.S. was partially funded by NIH/NIGMS R25 GM061347.

Author Contributions

P.P.C. and Y.T. designed research; S.S. and P.P.C. performed research; all authors analyzed data and wrote the paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-19944-4.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Prem P. Chapagain, Email: chapagap@fiu.edu

Yuk-Ching Tse-Dinh, Email: ytsedinh@fiu.edu.

References

- 1.Poirel L, Kieffer N, Liassine N, Thanh D, Nordmann P. Plasmid-mediated carbapenem and colistin resistance in a clinical isolate of Escherichia coli. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2016;16:281. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu YY, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2016;16(2):161–168. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alanis AJ. Resistance to Antibiotics: Are We in the Post-Antibiotic Era? Arch. Med. Res. 2005;36:697–705. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO, Global tuberculosis report, http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/ (2017)

- 5.Engstrom, A. Fighting an old disease with modern tools: characteristics and molecular detection methods of drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infectious diseases (London, England) JID 101650235 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Pommier Y. Drugging Topoisomerases: Lessons and Challenges. ACS chemical biology. 2013;8:82–95. doi: 10.1021/cb300648v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tse-Dinh Y. Bacterial topoisomerase I as a target for discovery of antibacterial compounds. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;37:731–737. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang JC. Cellular roles of DNA topoisomerases: a molecular perspective. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2002;3:430+. doi: 10.1038/nrm831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vos SM, Tretter EM, Schmidt BH, Berger JM. All tangled up: how cells direct, manage and exploit topoisomerase function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011;12:827–841. doi: 10.1038/nrm3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schoeffler AJ, Berger JM. DNA topoisomerases: harnessing and constraining energy to govern chromosome topology. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2008;41:41–101. doi: 10.1017/S003358350800468X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tse-Dinh Y. Targeting bacterial topoisomerase I to meet the challenge of finding new antibiotics. Future medicinal chemistry. 2015;7:459–471. doi: 10.4155/fmc.14.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng B, Shukla S, Vasunilashorn S, Mukhopadhyay S, Tse-Dinh Y. Bacterial Cell Killing Mediated by Topoisomerase I DNA Cleavage Activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:38489–38495. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509722200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ravishankar S, et al. Genetic and chemical validation identifies Mycobacterium tuberculosis topoisomerase I as an attractive anti-tubercular target. Tuberculosis. 2015;95(5):589–598. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmed W, Menon S, Godbole AA, Karthik PVDNB, Nagaraja V. Conditional silencing of topoisomerase I gene of Mycobacterium tuberculosis validates its essentiality for cell survival. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2014;353(2):116–123. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown ED, Wright GD. Antibacterial drug discovery in the resistance era. Nature. 2016;529:336–343. doi: 10.1038/nature17042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bowling, J. J., Shadrick, W. R., Griffith, E. C. & Lee, R. E. in Special Topics in Drug Discovery (eds Chen, T. & Chai, S. C.) Ch. 02 (InTech, Rijeka, 2016).

- 17.Bajorath J, Decornez H, Furr JR, Kitchen DB. Docking and scoring in virtual screening for drug discovery: methods and applications. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2004;3:935+. doi: 10.1038/nrd1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan K, Cao N, Cheng B, Joachimiak A, Tse-Dinh Y. Insights from the Structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Topoisomerase I with a Novel Protein Fold. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2016;428:182–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lagorce D, Sperandio O, Galons H, Miteva MA, Villoutreix BO. FAF-Drugs2: Free ADME/tox filtering tool to assist drug discovery and chemical biology projects. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:396. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baell, J. & Walters, M. A. Chemistry: Chemical con artists foil drug discovery. Nature513, 481–482, 483 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Zhu C, Tse-Dinh Y. The Acidic Triad Conserved in Type IA DNA Topoisomerases Is Required for Binding of Mg(II) and Subsequent Conformational Change. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:5318–5322. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Z, Cheng B, Tse-Dinh Y. Crystal structure of a covalent intermediate in DNA cleavage and rejoining by Escherichia coli DNA topoisomerase I. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108:6939–6944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100300108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandhaus S, et al. Small-Molecule Inhibitors Targeting Topoisomerase I as Novel Antituberculosis Agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016;60:4028–4036. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00288-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amaral L, Viveiros M. Why thioridazine in combination with antibiotics cures extensively drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2012;39:376–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coelho T, et al. Enhancement of antibiotic activity by efflux inhibitors against multidrug resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates from Brazil. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2015;6:330. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Godbole AA, et al. Targeting Mycobacterium tuberculosis Topoisomerase I by Small-Molecule Inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015;59:1549–1557. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04516-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ekins S, et al. Machine learning and docking models for Mycobacterium tuberculosis topoisomerase I. Tuberculosis. 2017;103:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization and multithreading. Journal of computational chemistry. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Boyle NM, et al. Open Babel: An open chemical toolbox. Journal of Cheminformatics. 2011;3:33–33. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qi Y, et al. CHARMM-GUI Martini Maker for Coarse-Grained Simulations with the Martini Force Field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:4486–4494. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang J, MacKerell AD. CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: Validation based on comparison to NMR data. Journal of computational chemistry. 2013;34:2135–2145. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phillips JC, et al. Scalable Molecular Dynamics with NAMD. Journal of computational chemistry. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Essmann U, et al. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:8577–8593. doi: 10.1063/1.470117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ryckaert J, Ciccotti G, Berendsen HJC. Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. Journal of Computational Physics. 1977;23:327–341. doi: 10.1016/0021-9991(77)90098-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brooks MM, Hallstrom A, Peckova M. A simulation study used to design the sequential monitoring plan for a clinical trial. Stat. Med. 1995;14:2227–2237. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780142006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. Journal of Molecular Graphics. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Annamalai T, Dani N, Cheng B, Tse-Dinh Y. Analysis of DNA relaxation and cleavage activities of recombinant Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA topoisomerase I from a new expression and purification protocol. BMC Biochem. 2009;10:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bansal S, et al. 3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl bis-benzimidazole, a novel DNA topoisomerase inhibitor that preferentially targets Escherichia coli topoisomerase I. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2012;67:2882–2891. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng B, et al. Identification of Anziaic Acid, a Lichen Depside from Hypotrachyna sp., as a New Topoisomerase Poison Inhibitor. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e60770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the relevant data are available upon request.