Abstract

Splenic rupture is an infrequent and underdiagnosed side effect of granylocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). We report the case of a 54-year-old woman with brain and bone metastasis in a lung adenocarcinoma who was admitted for faintness 28 days after a G-CSF injection. Abdominal CT scan confirmed the diagnosis of splenic rupture. A conservative treatment was chosen using a peritoneal cleansing during laparoscopic surgery. Clinicians should be aware of this rare toxicity as it could be severe, but easily reversible using appropriate surgical treatment. Even if prognosis remains poor for patients with lung cancer, invasive procedures could be considered in this rapidly evolving setting, especially in case of reversible adverse event.

Keywords: lung cancer (oncology), unwanted effects / adverse reactions

Background

Splenic rupture is an infrequent and poorly recognised side effect of granylocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). An recent review of the literature on G-CSF-associated adverse events reported 11 cases of splenic rupture: four in healthy adult donors of peripheral bloodstem cell, five in patients with haematological diseases and two in patients receiving chemotherapy for non-advanced cancer.1 Here, we report the first case of splenic rupture in patient treated for an advanced non-haematological malignancy and discuss the importance of a multidisciplinary approach of life-threatening events in this poor prognosis setting.

Case presentation

A 54-year-old woman was diagnosed with lung adenocarcinoma of the right upper lobe, initially revealed by insomnia-related pain related to a rib metastasis. Her tumour was staged T3N3M1b (tumour, node, metastases (TNM); bone and brain), according to the Eighth Edition of the TNM Classification for Lung Cancer.2 She had no medical history except active smoking evaluated at 20 pack-years. Routine molecular biology identified a KRAS G12C mutation in tumour samples. No mutation on EGFR, BRAF, HER2 and PI3KCA or rearrangement on ALK or ROS1 gene was detected.

First-line chemotherapy by 4 cycles of cisplatin–pemetrexed was proposed because of her excellent general condition. She experienced an overall good tolerability except digestive toxicity (nausea and vomiting grade 2) and haematological toxicity (neutropenia grade 2) after her third cycle. Consequently, a prophylactic treatment of febrile neutropenia was prescribed by 6 mg of pegfilgrastim according to international guidelines.3

Eight days after her fourth cycle of chemotherapy and first injection of pegfilgrastim, she was admitted in the emergency unit for faintness. At admission, she presented low blood pressure (85/50 mm Hg), tachycardia (95 bpm) and hypothermia (35.9°C) along with deterioration of her general status. Physical examination only revealed a bloated abdomen.

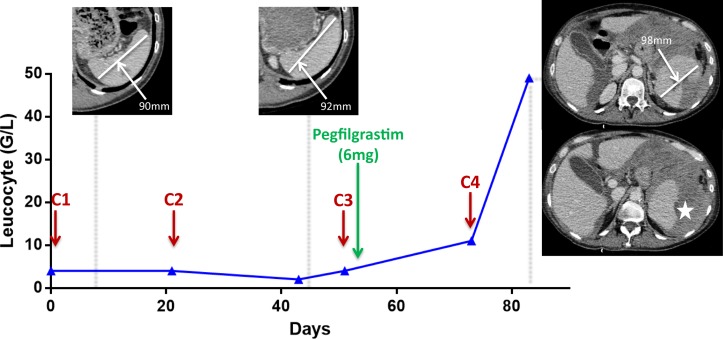

Biological test confirmed the presence of anaemia (6 g/dL), thombopenia (95 G/L) and white cell count increase (48.8 G/L) (cf. figure 1).

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the leucocyte count from the first cycle of chemotherapy to the splenic rupture. Chemotherapy injections are represented by red arrows over time course. Upper panels show the measurement of longest spleen diameter. Star displays the splenic rupture.

In this context of haemodynamic failure, the patient was referred to intensive care physicians for intensive care unit admission. Because of the underlying poor prognosis of metastatic cancer, the medical team decided to provide best supportive care and the patient received 5 packed red blood cells and intravenous morphine. However, her condition remained stable for 48 hours and abdominal CT scanner (CT scan) allowed the diagnosis of hemoperitoneum secondary to splenic rupture without observed active bleeding (cf. figure 1).

After multidisciplinary staff meeting, a conservative treatment was chosen and the patient underwent a peritoneal cleansing through laparoscopic surgery 3 days after initial admission. A diffuse hemoperitoneum related to a partial rupture located in the superior part of the spleen was confirmed during the surgery. No evidence of tumour invasion in the spleen or the peritoneum was observed.

Outcome and follow-up

There was no complication to surgery. A control CT scan done 1 week after the surgery showed no recurrence of bleeding and confirmed the stability of her thoracic malignancy. Chemotherapy and G-CSF had been discontinued temporarily and the patient recovered her initial general condition allowing subsequent cycles of chemotherapy.

Discussion

We describe here the first case of splenic rupture secondary to pegfilgrastim administration in the setting of advanced lung cancer. Even if the precise underlying mechanism remains uncertain until now, a prospective study published in 2009 reported an increase in the spleen volume under G-CSF treatment.4 Some authors speculate that massive increase of immature myeloid cell density (mainly granulocyte precursors) in the spleen through extramedullar haematopoiesis could cause the splenic rupture.5–8 In our case, the maximum diameter of the spleen increased by 6.1% after G-CSF injection compared with baseline CT scans, which is coherent with this hypothesis (cf. figure 1).

First-line treatment of non-small cell lung cancer without oncogene addiction is cisplatin-based doublet chemotherapy. According to many groups, G-CSF is recommended when the risk of febrile neutropenia is higher than 20%. When leucocyte count exceeds 50 G/L at nadir, or 70 G/L in case of haematopoietic stem cell stimulation, G-CSF should be interrupted.9 In our case, the patient had received a unique dose of G-CSF and no biological control had been planned. Until now, recommendations on G-CSF management do not include systematic leucocyte count monitoring, even with non-pegylated molecules requiring multiple injections.3

Splenic rupture is a potential toxicity of G-CSF that oncologists should be aware. Despite the severity of the clinical picture, prompt recognition and specific treatment generally allow a non-fatal outcome. However, the poor prognosis of our patient led to discrepancies in the therapeutic strategy proposed by the medical team. Despite no critical care admission, the patient remained stable and invasive procedures were then engaged. A recent study demonstrated that critical care admission for patients with non-resectable lung cancers had to be considered, as 69% of patients remained alive 3 months after discharge.10 As the therapeutic opportunities for lung cancer are constantly expanding, notably due to the emergence of immune checkpoint inhibitors, we can argue that the number of patients eligible for critical care would probably increase in the near future. Therefore, multidisciplinary concertation, including oncologists, emergency physicians and pulmonologists, is of prime importance to select the relevant therapeutic strategy.

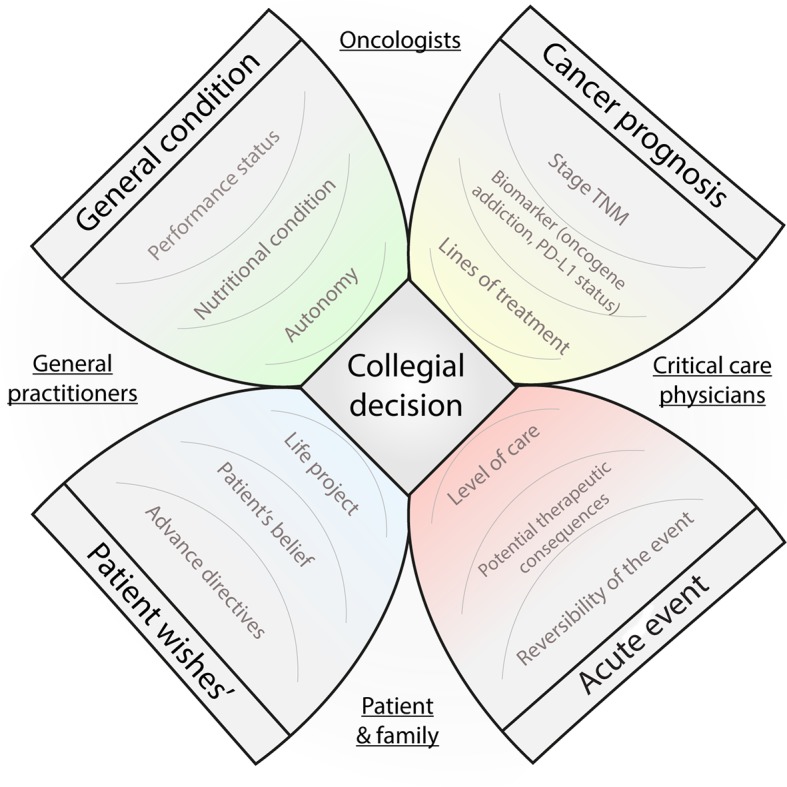

In our case, even if splenic rupture was a potentially lethal complication, it was an intercurrent and treatable event, not related to the malignancy evolution. In our experience, the decision of invasive therapeutic strategy should be centred on four key information: the patient wishes, his general condition, the prognosis of his malignancy and the reversibility of the acute event. Moreover, specifically in thoracic oncology, we think that predictive biomarkers (eg, oncogene addiction and Programmed Death Ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression) should now be implemented in the decision of critical care admission in this setting (figure 2), as emerging therapeutic options could translate into longer survival.

Figure 2.

Flower diagram representing the key information in order to discuss critical care admission in thoracic oncology. TNM, tumour, node, metastases. PD-L1 : Programmed Death Ligand 1

Learning points.

Granylocyte colony-stimulating factor-induced splenic rupture is a potentially life-threatening event that oncologists should recognise early.

As it could be treated efficiently without morbidity, invasive procedures should be considered even in poor prognosis patients.

Rapidly changing field of advanced lung cancer therapies and subsequent survival improvement bring to light new ethics issues that medical community will have to deal with in the near future.

Footnotes

Contributors: SB and HL contributed to conception and design of the manuscript. SB was responsible for the literature review. SB was responsible for clinical data collection. CR and FT were responsible for figures. All authors were responsible for manuscript editing and final approval of the article. CR takes responsibility for the paper as a whole.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Tigue CC, McKoy JM, Evens AM, et al. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor administration to healthy individuals and persons with chronic neutropenia or cancer: an overview of safety considerations from the Research on Adverse Drug Events and Reports project. Bone Marrow Transplant 2007;40:185–92. 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC lung cancer Staging Project: proposals for revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (Eighth) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:39–51. 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klastersky J, de Naurois J, Rolston K, et al. Management of febrile neutropaenia: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol 2016;27(suppl 5):v111–8. 10.1093/annonc/mdw325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stiff PJ, Bensinger W, Abidi MH, et al. Clinical and ultrasonic evaluation of spleen size during peripheral blood progenitor cell mobilization by filgrastim: results of an open-label trial in normal donors. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2009;15:827–34. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Malley DP, Whalen M, Banks PM. Spontaneous splenic rupture with fatal outcome following G-CSF administration for myelodysplastic syndrome. Am J Hematol 2003;73:294–5. 10.1002/ajh.10317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veerappan R, Morrison M, Williams S, et al. Splenic rupture in a patient with plasma cell myeloma following G-CSF/GM-CSF administration for stem cell transplantation and review of the literature. Bone Marrow Transplant 2007;40:361–4. 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nuamah NM, Goker H, Kilic YA, et al. Spontaneous splenic rupture in a healthy allogeneic donor of peripheral-blood stem cell following the administration of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (g-csf). A case report and review of the literature. Haematologica mai 2006;91:ECR08. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arshad M, Seiter K, Bilaniuk J, et al. Side effects related to cancer treatment: CASE 2. Splenic rupture following pegfilgrastim. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:8533–4. 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith TJ, Bohlke K, Lyman GH, et al. Recommendations for the Use of WBC Growth Factors: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:3199–212. 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.3488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toffart AC, Minet C, Raynard B, et al. Use of intensive care in patients with nonresectable lung cancer. Chest 2011;139:101–8. 10.1378/chest.09-2863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]