Abstract

Objectives

To assess time trends in symptomatic peripheral artery disease (PAD) incidence and prevalence, and secondary preventive therapy.

Design

Cohort study using The Health Improvement Network.

Setting

UK primary care.

Participants

Individuals aged 50–89 years identified annually between 2000 and 2014. Participants with symptomatic PAD were identified using Read codes.

Outcome measures

Incidence and prevalence of symptomatic PAD from 2000 to 2014, overall and by sex and age. Proportion of patients prescribed secondary preventive therapy with acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), clopidogrel, an ACE inhibitor, an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) and/or a statin.

Results

The incidence of symptomatic PAD per 10 000 person-years decreased over time, from 38.6 (men: 51.0; women: 28.7) in 2000 to 17.3 (men: 23.1; women: 12.4) in 2014. The prevalence of symptomatic PAD decreased from 3.4% (men: 4.5%; women: 2.5%) in 2000 to 2.4% (men: 3.1%; women: 1.7%) in 2014. Incidence and prevalence decreases were observed in all age groups. The proportions of patients prescribed ASA monotherapy, clopidogrel monotherapy and dual antiplatelet therapy in the 2 months after PAD diagnosis were 42.7%, 2.9% and 2.5%, respectively, during 2000–2003, and 44.7%, 11.0% and 5.2%, respectively, during 2012–2014. For ACE inhibitor/ARB therapy and statins, proportions in the 2 months after diagnosis were 30.2% and 31.2%, respectively, during 2000–2003, and 45.1% and 65.9%, respectively, during 2012–2014.

Conclusion

The incidence and prevalence of symptomatic PAD diagnosed in UK primary care are decreasing. A large proportion of the population with PAD in clinical practice does not receive guideline-recommended secondary prevention therapy.

Keywords: epidemiology, primary care, vascular medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is, to our knowledge, the largest study to date of time trends in peripheral artery disease (PAD) incidence and prevalence in the UK.

Data are from electronic medical records in The Health Improvement Network, which has demonstrated validity for use in pharmacoepidemiological studies.

Patients’ anonymised medical records were reviewed manually to validate the selected diagnostic Read codes used to identify symptomatic PAD in a random sample.

Potential limitations include possible changes over time in the source population and in how PAD is diagnosed in UK primary care, which would have affected the secular incidence and prevalence trend patterns.

Introduction

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) causes leg pain or discomfort, most commonly occurring on exertion and resolving after rest (intermittent claudication), although some individuals have no obvious symptoms even when functional impairment is noticeable on testing.1 Individuals with PAD are at increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI), ischaemic stroke and death.2 3 To reduce the risk of cardiovascular (CV) events, US and European guidelines recommend antiplatelet therapy and statins for all individuals with symptomatic PAD, and antihypertensive therapy for those with concomitant hypertension.4–7 ACE inhibitors may also reduce CV risk in symptomatic patients with PAD.4–7

The key risk factors for PAD are similar to those for other CV diseases, and include smoking, increasing age, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and dyslipidaemia.8 9 In recent years, the prevalence patterns of PAD risk factors have been changing substantially. Smoking prevalence is decreasing,10 but there is an increase in the prevalence of diabetes mellitus. Advances in treatment and in the implementation of processes of care have resulted in individuals with coronary heart disease and cerebrovascular disease now surviving to older ages, which is when PAD tends to manifest itself.

Whereas rates of MI and ischaemic stroke are declining in most countries,11–13 secular incidence and prevalence trends for PAD are less clear. A recent meta-analysis reported an increase in the prevalence of PAD (assessed using the Ankle–Brachial Index (ABI)) in high-income countries from 2000 to 2010.9 The analysis included data from 10 high-income countries including the USA and four European countries, but not the UK. Age-standardised prevalence data for symptomatic PAD from the US State of Health report show only minimal changes (<0.2%) from 1990 to 2010.14 The aim of the current study was to determine secular trends in the incidence and prevalence of symptomatic PAD and of secondary preventive therapy in a large, representative primary care population in the UK.

Methods

Study design and data source

This was a retrospective observational cohort study. Data were collected from The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database in the UK. THIN is an electronic medical research database that contains fully anonymised data on approximately 11 million patients collected from participating primary care practices in the UK.15 The data in THIN are from all patients in participating practices and are recorded during each consultation with the primary care physician/nurse, leaving no scope for selective participation or reporting. Patients included in THIN are representative of the UK general population.15 The Read classification is used to code specific diagnoses,16 and a drug dictionary based on data from the Gemscript classification is used to code drugs.17

Study cohorts

Source population

Patients aged 50–89 years were identified in THIN, annually between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2014. To be eligible for entry into the study, patients had to have been enrolled with their primary care physician for at least 2 years, to have visited their primary care physician at least once during that time and to have a computerised prescription history for at least 2 years before study entry. These inclusion criteria helped to ensure that study participants were making use of healthcare services offered by their primary care practice and had historical information available.

Incident and prevalent symptomatic PAD

For each year during the follow-up period, individuals with evidence of symptomatic PAD were identified by an automated database search using Read codes indicative of a symptomatic PAD diagnosis and/or related surgical procedures (online supplementary table S1). For PAD incidence and secular trends, the date of the first entry of a PAD diagnosis in the THIN database was set as the index date. For prevalent PAD, each patient’s start date was set as the date when the study inclusion criteria (as listed above) were met.

bmjopen-2017-018184supp001.pdf (126.3KB, pdf)

The positive predictive value of the automated database search to identify patients with symptomatic PAD was assessed in a random validation sample of 400 of the identified patients. Patients’ anonymised medical records, which included free-text comments from the primary care physicians, were reviewed manually. The diagnosis was confirmed in 97.0% of individuals (194/200) with incident PAD and in 99.0% of patients (198/200) with prevalent PAD, thereby confirming the positive predictive validity of the selected diagnostic Read codes used to identify symptomatic PAD.

Statistical analyses

Annual incidence and prevalence were determined for the years 2000–2014. The annual incidence was calculated by dividing the number of individuals with newly diagnosed PAD in a particular year by the contribution of all study participants at risk (free of PAD) in that year. To calculate the annual prevalence, the sum of the number of individuals with a history of PAD plus the number of individuals with newly diagnosed PAD in a particular year was divided by the total population meeting the study eligibility criteria. The time trends in the proportions of patients prescribed therapy with acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), clopidogrel, an ACE inhibitor, an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) and/or a statin in the 12 months before and 12 months after an incident PAD diagnosis were also assessed.

Results

Time trends in incidence and prevalence

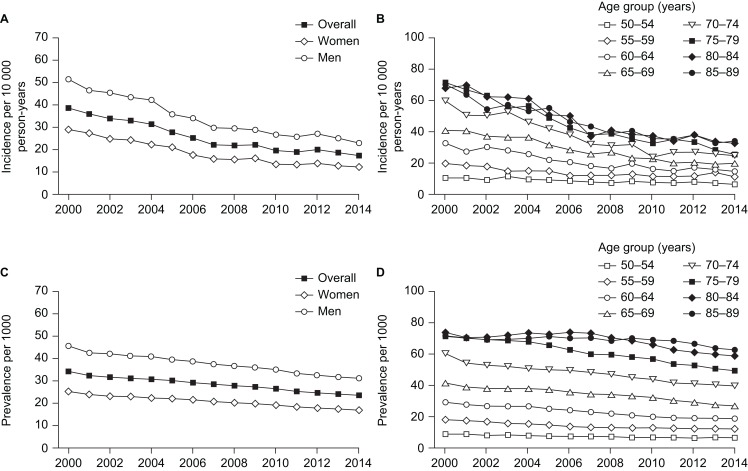

Time trends in the incidence and prevalence of PAD from 2000 to 2014, overall and separately by sex and age group, are shown in figure 1. The incidence of PAD decreased steadily over time, from 38.55 per 10 000 person-years in 2000 to 17.33 per 10 000 person-years in 2014 (figure 1A). The incidence was higher in men than in women: in 2000 it was 50.96 per 10 000 person-years in men and 28.70 per 10 000 person-years in women, and in 2014 it was 23.05 per 10 000 person-years and 12.37 per 10 000 person-years, respectively. Decreases in incidence over time were observed in all age groups (figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Trends from 2000 to 2014 in peripheral artery disease: (A) incidence, overall and according to sex; (B) incidence according to age group; (C) prevalence, overall and according to sex; and (D) prevalence according to age group.

The incidence of PAD was higher in patients with a history of ischaemic heart disease at the study start date than in those with no such history (online supplementary table S2). The incidence of PAD decreased over time at a similar rate in patients with a history of ischaemic heart disease (from 93.5 per 10 000 person-years in 2000 to 43.5 per 10 000 person-years in 2014) and those without a history of ischaemic heart disease (from 30.7 per 10 000 person-years in 2000 to 14.5 per 10 000 person-years in 2014).

The overall decrease in incidence of PAD from 2000 to 2014 was paralleled by a decrease in prevalence of the disease (figure 1C). The prevalence of PAD decreased from 3.42% (men: 4.53%; women: 2.52%) in 2000 to 2.37% (men: 3.12%; women: 1.70%) in 2014. Decreases in prevalence over time were observed in all age groups (figure 1D).

Time trends in demographics and comorbidities

Noticeable changes over time among patients with incident PAD diagnosed in 2000, 2005, 2010 or 2014 included increases in the proportions of patients who were obese (body mass index ≥30 kg/m2) and individuals who had prescriptions for five or more medications (online supplementary table S3). The proportion of current smokers decreased initially, from 39.5% among patients diagnosed in 2000 to 35.4% among those diagnosed in 2004, and then remained relatively constant thereafter. In the general population in THIN (ie, the study source population), a decline in the proportion who were current smokers was observed over time, from 22.0% in the year 2000 to 14.8% in 2014 (note: these data exclude patients for whom information on smoking status was not known, which in 2000 and 2014 equalled 10.1% and 0.1%, respectively, among those diagnosed with incident PAD, and 14.0% and 0.3%, respectively, among the study source population).

Regarding comorbidity patterns, ischaemic heart disease prevalence without MI declined over time, with rates of 34.0%, 32.8%, 29.5% and 26.4% in the years 2000, 2005, 2010 and 2014, respectively. However, increases in prevalence over time were observed for diagnoses of diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, cancer, depression and dementia. The age and sex distributions were similar over time.

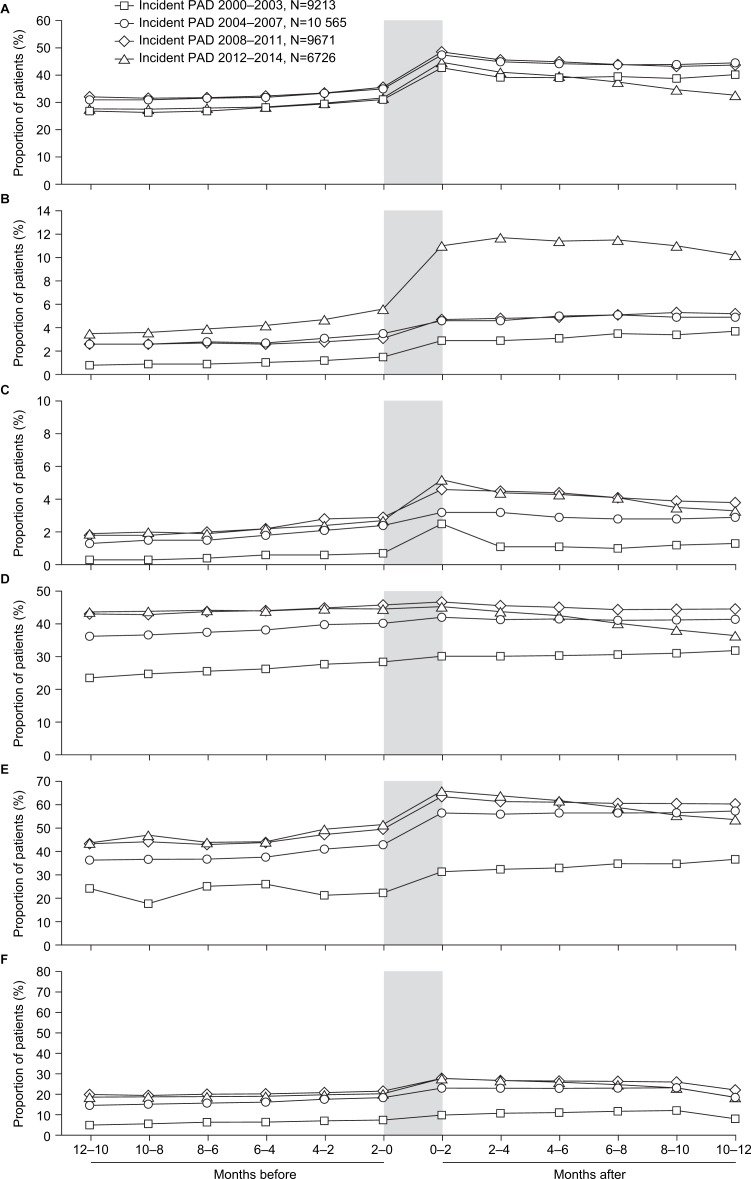

Time trends in treatment patterns

Time trends in treatment patterns in the 12 months before and 12 months after an incident diagnosis of PAD are shown in figure 2. Prescription rates increased at the time of the incident PAD diagnosis. ASA monotherapy was the most commonly prescribed antiplatelet therapy during the study period. Prescription rates for antiplatelet therapy in the 2 months after diagnosis in the years 2000–2003, 2004–2007, 2008–2011 and 2012–2014 were 42.7%, 47.4%, 48.4% and 44.7% for ASA, 2.9%, 4.6%, 4.7% and 11.0% for clopidogrel, and 2.5%, 3.2%, 4.6% and 5.2% for dual antiplatelet therapy, respectively.

Figure 2.

Time trends in the proportions of patients prescribed (A) acetylsalicylic acid monotherapy, (B) clopidogrel monotherapy, (C) dual antiplatelet therapy, (D) an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker, (E) a statin, or (F) combined therapy with an antiplatelet, plus an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker, plus a statin in the 12 months before and 12 months after an incident diagnosis of PAD. Shaded area highlights the 2 months before and 2 months after the PAD diagnosis. PAD, peripheral artery disease.

For ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy, prescription rates in the 2 months after diagnosis in the years 2000–2003, 2004–2007, 2008–2011 and 2012–2014 were 30.2%, 41.9%, 46.5% and 45.1%, and for statin therapy they were 31.2%, 56.5%, 63.6% and 65.9%, respectively. The proportion of patients with a prescription for an ACE inhibitor or ARB remained relatively similar before PAD diagnosis compared with after diagnosis in the earlier three study periods, but decreased after diagnosis in the most recent (2012–2014) study period. The proportion of patients with a statin prescription increased after an incident PAD diagnosis. In the most recent study period, it decreased again in the months after the diagnosis, although this trend was less pronounced when the analysis was restricted to practices with at least 1 year of data collection after the start date in the 2012–2014 subgroup (online supplementary figure S1), suggesting differences between practices in their end-of-year data collection rather than an actual decline in statin prescriptions.

Although the proportion of patients with prescriptions for all three therapies (an antiplatelet agent, plus an ACE inhibitor or ARB, plus a statin) in the 12 months before and 12 months after an incident diagnosis increased after 2000–2003 and also rose at PAD diagnosis, it remained below 30% at all times. Prescription rates for the three therapies combined in the 2 months after diagnosis in the years 2000–2003, 2004–2007, 2008–2011 and 2012–2014 were 9.7%, 22.6%, 27.3% and 27.6%, respectively.

Discussion

The results of this large observational study, conducted in ‘real-life’ clinical practice, showed a steady decline over time in the incidence and prevalence of symptomatic PAD in UK primary care. The incidence in patients with ischaemic heart disease was approximately three times higher than in those without ischaemic heart disease, but both groups showed similar rates of decline. Ischaemic heart disease prevalence declined over time, potentially underlying the parallel secular trend in PAD prevalence and suggesting general improvements in overall CV health over time in the UK.

The decline in incidence of PAD between 2000 and 2014 was observed across all age groups except the group aged 50–59 years, in which the incidence remained largely similar over time. An important factor in the decrease in PAD incidence could be an increased uptake over time of secondary CV prevention strategies. In the current study, when assessing the 12 months either side of PAD diagnosis, an increase over time was observed in the prescription rate for antiplatelet, ACE inhibitor, ARB and/or statin therapy, which may have delayed or prevented the onset of PAD in at-risk patients. Declining rates of smoking and increasing rates of diabetes in recent years in the UK may have influenced trends in the incidence of PAD, but it should be recognised that there is likely to be a considerable lag effect with these risk factors affecting the development of chronic atherosclerotic diseases, including PAD, over many years of an individual’s life. Thus, short-term changes in risk factor prevalence from 2000 to 2014 in our study might have only a limited impact on incidence of PAD during that period.

Results of a recent meta-analysis indicated that the prevalence of PAD increased from 2000 to 2010 in high-income countries.9 Data on temporal trends in PAD prevalence suggest that any observed prevalence increases over time may be due to an ageing population, with age-standardised prevalence data for symptomatic PAD reporting only minimal changes over time.14 The current study, which included only patients aged 50 years or older, observed a symptomatic PAD prevalence that ranged from 3.42% in 2000 to 2.37% in 2014. These rates are similar to those reported in other population-based studies in the USA and Europe that include a minimum age cut-off. In both the US Life Line Screening programme (participants aged ≥40 years; study years 2003–2008)18 and the Spanish HERMEX study (participants aged ≥50 years; study years: 2007–2009),19 PAD prevalence was 3.7%. Slightly higher prevalences of 7.6% and 5.8%, respectively, were reported in a Spanish primary healthcare study (participants aged ≥50 years; study years 2006–2008)20 and the German Heinz Nixdorf Recall study (participants aged ≥45 years; study years 2000–2003).21

There is a paucity of published data regarding the incidence of PAD.8 Long-term results from a German study conducted in primary care (the ‘getABI’ study), which enrolled patients aged 65 years and older, found a PAD incidence of 203 per 10 000 person-years. In our study, a lower PAD incidence than in the German study was observed in the older age groups, ranging from approximately 30 per 10 000 person-years to 70 per 10 000 person-years (figure 1).

The reported incidence and prevalence across studies will depend on whether they are obtained using recorded diagnoses, as in the current study, or by assessing all study patients for PAD symptoms and signs (eg, via the ABI). The latter approach will tend to result in higher observed incidence and prevalence. When assessing secular trends, it is essential to ensure that the methodology for identifying patients with PAD is similar across all time points, as was the case in the current study.

Risk factors for PAD should be carefully managed in primary care. Patients with PAD are at risk of progressing to critical limb ischaemia, irrespective of whether their PAD is symptomatic or asymptomatic. Patients who are at high risk for PAD need to be identified and screened, and adequate secondary prevention strategies implemented where appropriate. In the real world this is often not the case as is manifest by, for example, continuing high rates of smoking. There is a need to take an aggressive approach to dealing with factors to reduce the risk of PAD and of future serious outcomes.

Guidelines on the management of PAD were first published by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) in August 20115 and by the UK National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in August 2012.22 Both recommend antiplatelet therapy in all individuals with symptomatic PAD. Antiplatelet therapy for the prevention of vascular events has also been included in the NICE PAD management pathway. Additional recommendations from the ESC and NICE include smoking cessation, and management of diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia.

Although the proportion of patients with PAD prescribed antiplatelet therapy increased over time in the current study, more than one-third of patients were not prescribed antiplatelet therapy with ASA, clopidogrel or combination therapy following an incident PAD diagnosis between 2012 and 2014. The proportion of patients with incident PAD who were prescribed a statin increased to approximately 66% at the time of PAD diagnosis during 2012–2014. The proportion prescribed an ACE inhibitor or ARB decreased slightly after diagnosis in 2012–2014. Prescribing for secondary preventive therapies tended to be highest following PAD diagnosis.

Our study has several key strengths. It is, to our knowledge, the largest study to date of time trends in PAD incidence and prevalence in the UK. Data are from electronic medical records in THIN. Patients included in THIN are representative of the UK general population in terms of age, sex and geographical location.15 THIN has demonstrated validity for use in pharmacoepidemiological studies.23 Patients’ anonymised medical records, which included free-text comments from the primary care physicians, were reviewed manually to validate the selected diagnostic Read codes used to identify symptomatic PAD in a random sample. Potential limitations include possible changes over time in the source population and in how PAD is diagnosed in UK primary care, which would have affected the secular incidence and prevalence trend patterns. PAD data were not assessed by race because patients’ race is not systematically captured in THIN.

In conclusion, results from this study suggest that the incidence and prevalence of symptomatic PAD are decreasing in the UK. Although prescription rates have increased over time, a large proportion of individuals diagnosed with PAD in the primary care setting do not receive guideline-recommended secondary prevention therapy.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: LC-S: conception and design of the work, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, critical revision of the article, approval of final draft. FGRF: data interpretation, critical revision of the article, approval of final draft. SJ: conception and design of the work, data interpretation, critical revision of the article, approval of final draft. AMA: conception and design of the work, data interpretation, critical revision of the article, approval of final draft. LAGR: conception and design of the work, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, critical revision of the article, approval of final draft.

Funding: This work was supported by AstraZeneca. Medical writing support was provided by Dr Anja Becher of Oxford PharmaGenesis, Oxford, UK, and was funded by AstraZeneca.

Competing interests: LC-S and LAGR are employees of CEIFE, which has received research funding from AstraZeneca Gothenburg, Mölndal, Sweden, and Bayer Pharma AG, Berlin, Germany. LAGR has also received honoraria for serving on scientific advisory boards for AstraZeneca and Bayer. FGRF has received honoraria for serving on scientific advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Bayer and Merck. SJ is an employee of AstraZeneca Gothenburg, Mölndal, Sweden. AMA is an employee of AstraZeneca Cambridge, Cambridge, UK.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description/these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Ethics approval: Multicentre Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All relevant source data are shown in the manuscript and supplementary files.

References

- 1.Olin JW, Sealove BA. Peripheral artery disease: current insight into the disease and its diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85:678–92. 10.4065/mcp.2010.0133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pande RL, Perlstein TS, Beckman JA, et al. . Secondary prevention and mortality in peripheral artery disease: National Health and Nutrition Examination Study, 1999 to 2004. Circulation 2011;124:17–23. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.003954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel MR, Becker RC, Wojdyla DM, et al. . Cardiovascular events in acute coronary syndrome patients with peripheral arterial disease treated with ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel: data from the PLATO Trial. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2015;22:734–42. 10.1177/2047487314533215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson JL, Halperin JL, Albert NM, et al. . Management of patients with peripheral artery disease (compilation of 2005 and 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline recommendations): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2013;127:1425–43. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828b82aa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tendera M, Aboyans V, Bartelink ML, et al. . ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral artery diseases: Document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteries: the Task Force on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Artery Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2011;32:2851–906. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, et al. . Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II). J Vasc Surg 2007;45:S5–S67. 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.12.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rooke TW, Hirsch AT, Misra S, et al. . 2011 ACCF/AHA Focused Update of the Guideline for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Artery Disease (updating the 2005 guideline): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:2020–45. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Criqui MH, Aboyans V. Epidemiology of peripheral artery disease. Circ Res 2015;116:1509–26. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fowkes FG, Rudan D, Rudan I, et al. . Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet 2013;382:1329–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61249-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. UK Office for National Statistics. Adult smoking habits in the UK. 2015. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandlifeexpectancies/bulletins/adultsmokinghabitsingreatbritain/2015 (accessed 28 Aug 2017).

- 11.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. . Heart disease and stroke statistics-2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015;131:e29–322. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moran AE, Forouzanfar MH, Roth GA, et al. . The global burden of ischemic heart disease in 1990 and 2010: the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Circulation 2014;129:1493–501. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.004046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nichols M, Townsend N, Scarborough P, et al. . Cardiovascular disease in Europe 2014: epidemiological update. Eur Heart J 2014;35:2950–9. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray CJ, Atkinson C, Bhalla K, et al. . The state of US health, 1990-2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA 2013;310:591–608. 10.1001/jama.2013.13805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bourke A, Dattani H, Robinson M. Feasibility study and methodology to create a quality-evaluated database of primary care data. Inform Prim Care 2004;12:171–7. 10.14236/jhi.v12i3.124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stuart-Buttle CD, Read JD, Sanderson HF, et al. . A language of health in action: Read Codes, classifications and groupings. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp 1996:75-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. In Practice Systems Ltd. Gemscript. http://www.inps.co.uk/

- 18.Savji N, Rockman CB, Skolnick AH, et al. . Association between advanced age and vascular disease in different arterial territories: a population database of over 3.6 million subjects. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:1736–43. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Félix-Redondo FJ, Fernández-Bergés D, Grau M, et al. . Prevalence and clinical characteristics of peripheral arterial disease in the study population Hermex. Rev Esp Cardiol 2012;65:726–33. 10.1016/j.rec.2012.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alzamora MT, Forés R, Baena-Díez JM, et al. . The peripheral arterial disease study (PERART/ARTPER): prevalence and risk factors in the general population. BMC Public Health 2010;10:38 10.1186/1471-2458-10-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kröger K, Stang A, Kondratieva J, et al. . Prevalence of peripheral arterial disease - results of the Heinz Nixdorf recall study. Eur J Epidemiol 2006;21:279–85. 10.1007/s10654-006-0015-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Peripheral arterial disease: diagnosis and management. 2012. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg147/resources/peripheral-arterial-disease-diagnosis-and-management-35109575873989 (accessed 3 Nov 2016).

- 23.Lewis JD, Schinnar R, Bilker WB, et al. . Validation studies of the health improvement network (THIN) database for pharmacoepidemiology research. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007;16:393–401. 10.1002/pds.1335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-018184supp001.pdf (126.3KB, pdf)