Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the cost-effectiveness and cost-utility of an internet-based perioperative care programme compared with usual care for gynaecological patients.

Design

Economic evaluation from a societal perspective alongside a stepped-wedge cluster-randomised controlled trial with 12 months of follow-up.

Setting

Secondary care, nine hospitals in the Netherlands, 2011–2014.

Participants

433 employed women aged 18–65 years scheduled for a hysterectomy and/or laparoscopic adnexal surgery.

Intervention

The intervention comprised an internet-based care programme aimed at improving convalescence and preventing delayed return to work (RTW) following gynaecological surgery and was sequentially rolled out. Depending on the implementation phase of their hospital, patients were allocated to usual care (n=206) or to the intervention (n=227).

Main outcome measures

The primary outcome was duration until full sustainable RTW. Secondary outcomes were quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), health-related quality of life and recovery.

Results

At 12 months, there were no statistically significant differences in total societal costs (€−647; 95% CI €−2116 to €753) and duration until RTW (−4.1; 95% CI −10.8 to 2.6) between groups. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for RTW was 56; each day earlier RTW in the intervention group was associated with cost savings of €56 compared with usual care. The probability of the intervention being cost-effective was 0.79 at a willingness-to-pay (WTP) of €0 per day earlier RTW, which increased to 0.97 at a WTP of €76 per day earlier RTW. The difference in QALYs gained over 12 months between the groups was clinically irrelevant resulting in a low probability of cost-effectiveness for QALYs.

Conclusions

Considering that on average the costs of a day of sickness absence are €230, the care programme is considered cost-effective in comparison with usual care for duration until sustainable RTW after gynaecological surgery for benign disease. Future research should indicate whether widespread implementation of this care programme has the potential to reduce societal costs associated with gynaecological surgery.

Trial registration number

NTR2933; Results.

Keywords: gynaecology, telemedicine, minimally invasive surgery, health economics, organisation of health services

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first economic evaluation on an internet-based care programme aimed at improving convalescence and preventing delayed return to work following gynaecological surgery.

The study was conducted alongside a cluster-randomised controlled trial allowing prospective collection of relevant cost and effect data.

The study was performed from a societal perspective, and costs associated with lost productivity included both absenteeism and presenteeism costs.

A latent barrier to future acceptance and implementation of the care programme lies in the fact that the costs and benefits of the care programme are separated between different types of stakeholders.

Introduction

At present, there is a transition of perioperative care from the hospital setting towards the home environment.1–4 The introduction of advanced surgical techniques in combination with the implementation of ‘fast-track’ clinical pathways has considerably reduced the length of postoperative hospital stays, and many (complex) surgeries are now being performed in an ambulatory setting.5–7 This is beneficial from the perspective of the healthcare system, as it leads to the containment of healthcare costs.1 8

However, costs associated with lost productivity following surgery contribute to the total societal costs of surgical procedures as well, and are mostly not taken into account. Moreover, there is considerable evidence that the duration of sick leave following gynaecological surgery generally exceeds the period considered appropriate by specialists.9 Therefore, preventing unnecessary prolonged recovery following gynaecological surgery may translate into considerable savings for society.

We developed an internet-based care programme for patients undergoing gynaecological surgery for benign disease, aimed at facilitating recovery after discharge and preventing delayed return to work (RTW).10 11 In this paper, we report on the cost-effectiveness and cost-utility of the internet-based care programme compared with usual care. The findings on clinical effectiveness were reported in a separate paper.12

Methods

Study design and participants

This economic evaluation was performed from a societal perspective and was carried out alongside a stepped-wedge cluster-randomised controlled trial comparing an internet-based care programme with usual care for patients undergoing benign gynaecological surgery. The study was done in the Netherlands between October 2011 and July 2014. The follow-up period was 12 months. The trial protocol has been published previously in accordance to Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials extended guidelines.9

The clusters in this trial were formed by separate hospitals. A total of nine hospitals participated, which were selected before the start of the trial. Hospitals were eligible if they performed at least 100 hysterectomies or laparoscopic adnexal surgeries annually and were located within 50 km of the VU medical centre, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Patients were recruited from the waiting lists for hysterectomy (abdominal, vaginal or laparoscopic) and laparoscopic adnexal surgery. Eligible participants were women aged 18–65 years who were employed for at least 8 hours a week (unpaid or paid employment or self-employed). We excluded patients who had severe benign comorbidity, had a malignancy, were pregnant, were computer or internet illiterate, were involved in a lawsuit against their employer, were on disability sick leave before surgery or had insufficient command of Dutch.

Randomisation and blinding

Randomisation took place at the level of the clusters and determined the order in which the intervention was implemented in the participating hospitals. The sequence was generated by a statistician using a computer-generated list of random numbers. A stepped-wedge approach was employed as it enabled us to study both the cost-effectiveness of the intervention and the implementation process.9

Patients, clinicians and researchers could not be blinded for the intervention. However, group allocation was concealed until patients had agreed to participate and provided written informed consent. Data analysts (EVAB and JEB) were masked to group allocation.

Intervention care programme and implementation strategy

The development and content of the intervention care programme have been described elsewhere in more detail.9 11 A multifaceted implementation strategy was employed to achieve maximal adoption of the care programme, targeting three different levels.

At the level of the organisation, the structure of healthcare was changed by the introduction of the interactive web portal that was accessible for patients as well as their healthcare professionals. In addition, care managers were trained to help patients identify possible barriers to resuming work activities and could assist, if necessary, in the planning and execution of work resumption, before and after surgery.

At the level of the healthcare professional, educational training sessions were organised to introduce an earlier developed guideline on postoperative convalescence recommendations to stimulate evidence-based patient education.10

At the patient level, the care programme consisted of two steps. First, all participants allocated to the intervention group received access to the web portal several weeks prior to their surgery (eHealth intervention). The interactive web portal facilitated self-management by providing patients with individual tailored convalescence recommendations throughout the entire surgical pathway as well as monitoring recovery postoperatively through an interactive self-assessment tool. Second, for those patients at risk of prolonged sick leave, a care manager was available to provide additional guidance in the process of resuming work activities (occupational intervention).

Usual care

Before the care programme was implemented in the hospitals, participating patients received usual care. Although considerable variation in usual care exists in the Netherlands, postoperative patients generally receive verbal instructions at discharge by a nurse and/or physician, sometimes accompanied by a letter or brochure. Usually, a postoperative consultation is planned 6 weeks after surgery. Due to Dutch legislation, employed patients who do not resume work within 6 weeks after the surgery are invited for a consultation with their occupational physician.

Main outcome measures

The primary outcome was duration until sustainable RTW defined as the resumption of own work or other work with equal earnings, for at least 4 weeks without (partial or full) recurrence of sick leave. This definition was adopted as interventions aimed at expediting RTW of sick-listed employees should also aim at reducing recurrence of sickness absence in order to sustain employees at work after initial RTW. Data on RTW were collected by means of monthly electronic sick leave calendars.

Quality-adjusted life year (QALY) was one of the secondary outcomes and was measured using the Dutch version of the European Quality of Life five-dimensional three-level questionnaire (EQ-5D-3L).13 The Dutch tariff was used to estimate the utility of EQ-5D-3L health states.14 QALYs were calculated by multiplying the utility with the amount of time a patient spent in a particular health state. Transitions between health states were linearly interpolated. Other secondary outcomes included health-related quality of life assessed by Short-Form Health Survey15 and recovery assessed by the Recovery Index.16 All secondary outcomes were assessed at baseline and at 2, 6, 12, 26 and 52 weeks follow-up.

Service use and costs

The intervention and implementation strategy costs consisted of costs related to implementing the new care programme. A bottom-up microcosting approach was used for estimating intervention costs, using detailed data regarding the quantity and unit prices of: (1) the training sessions of involved healthcare professionals (clinical staff, occupational physicians and occupational therapist), (2) the eHealth intervention (hosting of web portal and administrator time) and (3) the occupational intervention (number and duration of consultations).17

Data on healthcare services used and support received by the participants were collected using electronic questionnaires during 1 year. Each month, the patient was asked to report service use over the previous month. Patients who were not sick listed and did not have any healthcare costs during three consecutive months received a shortened version of the questionnaire. In case of no response, electronic reminders were sent after 1 and 2 weeks. If participants did not respond to the electronic reminders either, an additional attempt was made to complete the missing data per email, mail or telephone every 3 months.

Only healthcare utilisation and support related to the gynaecological surgery were collected and included the following categories: surgery and initial hospitalisation, primary and secondary care including complementary medicine, medication and medical aids, home care and informal help.

Service utilisation was valued using Dutch standard costs.18 If these were unavailable, prices according to professional organisations were used. The prices of prescribed drugs were estimated using the prices of the Royal Dutch Society for Pharmacy.19

Productivity loss

Absenteeism costs were calculated using the human capital approach. The net number of sick leave days during follow-up was multiplied by the estimated costs of 1 day of sick leave for females, stratified for age.18 In case of partial sick leave, we assumed that participants were 100% productive during the hours of partial work resumption.

Presenteeism (ie, reduced productivity while at work) was assessed monthly after full resumption of work using two items of the ‘Productivity and Disease Questionnaire’.20 Patients were asked to report the quantity (q1) and quality (q2) of the work performed during the latest day at work on an 11-point scale, ranging from ‘nothing/very bad quality’ (0) to ‘same as normal’ (10).

The level of presenteeism (Presday) on the latest day at work was calculated using the following formula: Presday=(1−((q1*q2)/100)).20 21 Assuming linearity, the level of presenteeism on the latest day at work was then extrapolated over the total month. The total number of workdays lost due to presenteeism was calculated (Presmonth) by multiplying the participants’ presenteeism level by their number of days worked during that month. Subsequently, presenteeism costs per month were calculated by multiplying Presmonth, by the estimated costs of 1 day of lost productivity.

The index year of the study was 2014. Discounting of costs was not necessary because the follow-up was 1 year.22

Statistical analysis

The sample size of the study (n=454) was calculated for detecting a relevant difference in RTW (HR 1.5) in the main outcome study.9 The economic evaluation was done according to the intention to treat principle. Missing cost and effect data during follow-up were imputed using multiple imputation by chained equations. Multiple imputation was done using SPSS V.16.0 with predictive mean matching. An imputation model containing demographic and prognostic variables was used to create five complete datasets after which the loss of efficiency was smaller than 5%.23 Rubin’s rules were used to pool effects and costs from the five imputed datasets.24

Differences in costs and effects were estimated using linear multilevel regression analyses, while adjusting for type of surgery. Clustering at the hospital-level and patient-level was accounted for in these multilevel models. For the cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analyses, we calculated incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) by dividing the incremental costs by the incremental effects. The ICER indicates the additional investments needed for the intervention to gain one extra unit of effect compared with usual care. In the ICER for duration until RTW, productivity costs due to sick leave were excluded from the cost estimates to avoid double counting.

We used non-parametric bootstrapping with 5000 replications to estimate 95% CIs around cost differences and the uncertainty surrounding the ICERs.25 To account for the clustering of data, bootstrap replications were stratified for hospital.26 Bootstrapped cost-effect pairs were plotted on cost-effectiveness planes (CE planes) and used to estimate cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEA curves). CEA curves show the probability that a treatment is cost effective in comparison with the control treatment at a specific ceiling ratio, which is the amount of money society is willing to pay to gain one extra unit of effect.

Sensitivity analyses

To assess whether protocol deviations influenced the treatment effect, a per-protocol analysis was performed. In addition, to assess the robustness of the results, we carried out three sensitivity analyses. First, we did a complete-case analysis to assess the cost-effectiveness of the interventions excluding patients who were lost to follow-up. Second, we replicated the cost-effectiveness analysis using the friction cost approach (FCA). The FCA assumes that costs are limited to the friction period (ie, the period needed to replace a sick worker). A friction period of 23 weeks and an elasticity of 0.8 were used. Third, an analysis from the healthcare perspective was performed including only healthcare costs.

All statistical analyses followed a predefined analysis plan and were done in SPSS (V.16.0) and STATA (V.12SE).

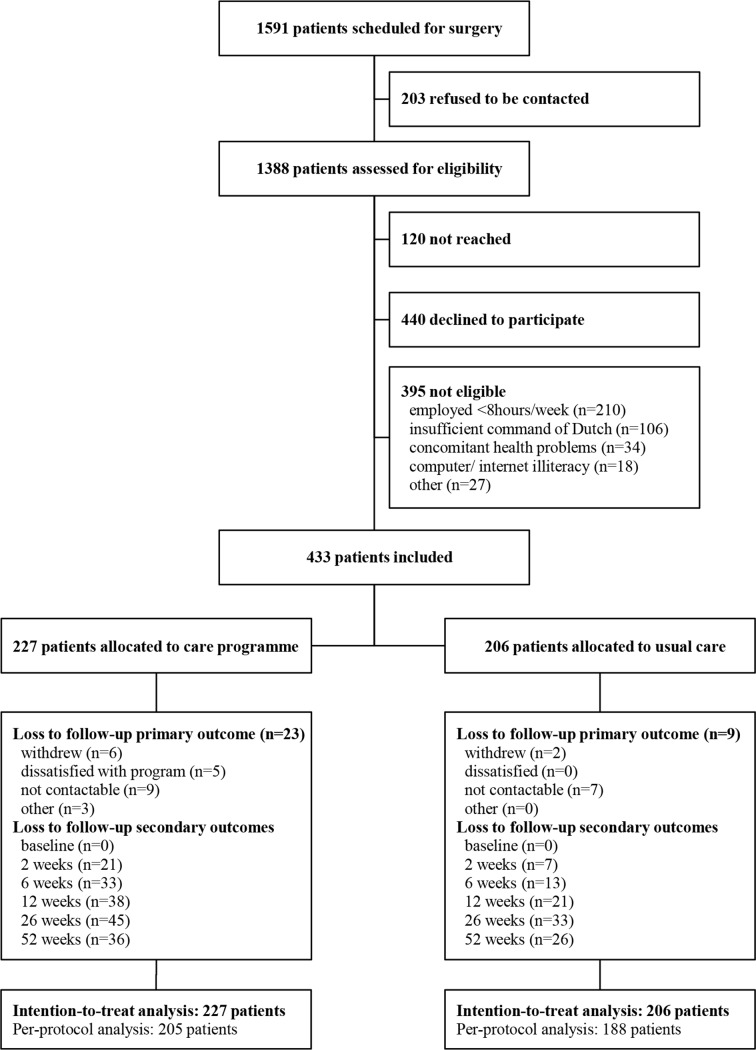

Results

Participants

During the study period, 1591 patients were scheduled for a hysterectomy and/or laparoscopic adnexal surgery in the participating hospitals. In total, 433 patients enrolled in the study, 206 patients during the control phase and 227 patients during intervention phase (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Trial profile.

Participants’ demographic and prognostic variables are presented in table 1. Complete follow-up data were obtained from 92.6% of the participants on the primary outcome RTW, from 71.8% on the secondary outcomes and 70.0% on healthcare utilisation. Baseline characteristics did not differ between participants with and without complete cost data, except that patients with complete data on healthcare utilisation used the internet more frequently than women with incomplete data.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of individual patients

| Care programme (n=227) | Usual care (n=206) | |

| Patient characteristics | ||

| Age (years) (mean±SD) | 46.1±7.3 | 45.6±6.7 |

| Dutch nationality | 220 (96.9%) | 202 (98.1%) |

| Internet use (days per week) | ||

| <1 | 2 (0.9%) | 3 (1.5%) |

| 1–2 | 9 (4.0%) | 10 (4.9%) |

| 3–5 | 45 (19.8%) | 42 (20.4%) |

| >5 | 171 (75.3%) | 151 (73.3%) |

| Education level* | ||

| Low | 25 (11.0%) | 17 (8.3%) |

| Intermediate | 88 (38.8%) | 100 (48.5%) |

| High | 114 (50.2%) | 89 (43.2%) |

| Surgery-related characteristics | ||

| Type of surgery | ||

| Adnexal surgery | 74 (32.6%) | 51 (24.8%) |

| Laparoscopic hysterectomy | 65 (28.6%) | 50 (24.3%) |

| Vaginal hysterectomy | 36 (15.9%) | 53 (25.7%) |

| Abdominal hysterectomy | 52 (22.9%) | 52 (25.2%) |

| Health-related characteristics | ||

| Perceived health status (mean±SD) | 75.8±16.5 | 76.9±16.7 |

| Work-related characteristics | ||

| Type of work | ||

| Salary employed | 194 (85.5%) | 175 (85.0%) |

| Self-employed | 28 (12.3%) | 28 (13.6%) |

| Voluntary work | 5 (2.2%) | 3 (1.5%) |

| Work hours per week (mean±SD) | 29.7±9.3 | 28.7±8.2 |

| Sick leave (3 months before surgery) | ||

| Absence from work† | 88 (38.8%) | 66 (32.0%) |

| Number of sick leave days (median (IQR)) | 4.0 (2–10) | 4.5 (2–11) |

| RTW expectation (long)‡ | 42 (18.5%) | 38 (18.4%) |

| RTW intention (low)§ | 45 (19.8%) | 67 (32.5%) |

Data are number of patients (%), unless otherwise indicated.

*Low=preschool or primary school; intermediate=secondary school; high=tertiary school, university or postgraduate.

†Defined as at least 1 day absence.

‡Defined as expectation longer than 3 weeks for adnexal surgery, longer than 6 weeks for laparoscopic or vaginal hysterectomy or longer than 8 weeks for abdominal hysterectomy.

§Higer scores indicate a higher intention to return to work, despite symptoms (range 1-5). A low intention was defined as score 1 or 2.

RTW, return to work.

Service use and costs

Table 2 presents the costs of self-reported service use per category over the 12 months of follow-up stratified by treatment group and the mean cost differences between both groups.

Table 2.

Costs associated with self-reported service used across treatment groups at 12 months of follow-up

| Cost category | Intervention mean (SEM) n=227 | Usual care mean (SEM) n=206 | Mean cost difference (95% CI)* |

| Healthcare costs | 3823 (99) | 4142 (134) | −61 (−361 to 218) |

| Surgery and initial hospitalisation costs | 3236 (64) | 3413 (58) | 34 (−118 to 174) |

| Primary care costs | 179 (24) | 167 (30) | 14 (−58 to 95) |

| Secondary care costs | 242 (42) | 458 (98) | −178 (−400 to −31) |

| Costs of medication and aids | 13 (4) | 10 (4) | 3 (−6 to 11) |

| Home help costs | 72 (24) | 94 (26) | −19 (−85 to 45) |

| Intervention | 80 (0) | NA | 80 (NA) |

| Lost productivity costs | 8443 (543) | 9653 (528) | −570 (−1909 to 692) |

| Costs of absenteeism from unpaid work | 1845 (224) | 2124 (299) | −144 (−756 to 282) |

| Costs of absenteeism from paid work | 6499 (425) | 7281 (344) | −424 (−1469 to 578) |

| Presenteeism costs | 99 (78) | 248 (127) | −154 (−458 to 82) |

| Total societal costs | 12 266 (596) | 13 795 (602) | −647 (−2116 to 735) |

*Uncertainty estimated using bootstrapping and corrected for clustering by hospital and type of surgery.

Costs are expressed in 2014 Euros (€1.00=₤0.85; $1.06).

Mean values summarise the costs derived after the imputation process.

Intervention costs were €80 per participant (online supplementary table 1). Total societal costs per patient were €12 266 in the intervention group and €13 795 in the usual care group. After correction for clustering by hospital and adjustment for surgery type, total societal costs in the intervention group were €647 lower compared with the usual care group, but this difference was not statistically significant (95% CI €−2116 to €753). In both groups, costs related to productivity losses were about two times higher than total healthcare costs. There were no statistical significant differences in healthcare costs between the intervention group and usual care group (€−61; 95% CI €−361 to €218) and lost productivity costs (€−570; 95% CI €−1909 to €692). Only costs for secondary care were significantly lower in the intervention group compared with the usual care group (€−178; 95% CI €−400 to €−31).

bmjopen-2017-017782supp001.pdf (240.1KB, pdf)

Effectiveness

The mean duration until RTW in the intervention group was 49.6 days versus 56.2 days in the usual care group. The adjusted difference in duration until RTW between intervention and usual care was −4.1 days, but this difference was not statistically significant (95% CI −10.8 to 2.6) (table 3). For the other outcomes, no statistically differences were found between both groups at 12 months either.

Table 3.

Effects across treatment groups at 12 months of follow-up

| Outcomes | Intervention mean (SEM) n=227 |

Usual care mean (SEM) n=206 |

Mean effect difference (95% CI)* |

| Duration until RTW (days) | 49.6 (2.7) | 56.2 (2.2) | −4.1 (−10.8 to 2.6) |

| QALYs gained | 0.96 (0.008) | 0.96 (0.007) | −0.001 (−0.023 to 0.020) |

| HR-QoL (SF-36) | |||

| PCS | 5.7† (0.7) | 6.7† (0.6) | −0.7 (−2.6 to 1.1) |

| MCS | 3.3† (0.7) | 3.7† (0.8) | −0.4 (−2.5 to 1.7) |

| Recovery (RI-10) | 24.3† (0.4) | 25.0† (0.5) | −0.6 (−2.0 to 0.9) |

*Uncertainty estimated using bootstrapping and corrected for clustering by hospital and type of surgery.

†Difference between baseline score and score at 12 months follow-up.

HR-QoL, health-related quality of life; MSC, mental component scale; PSC, physical component scale; QALY, quality-adjusted life year; RI, recovery index; RTW, return to work; SF, short form.

Cost-effectiveness

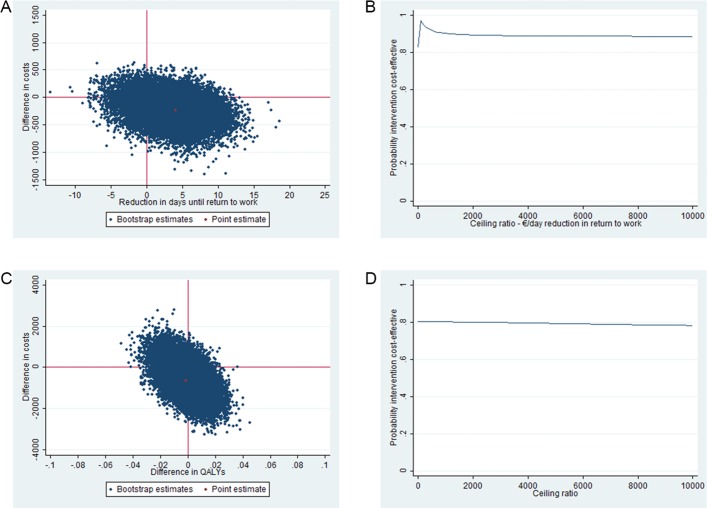

The results of the cost-effectiveness analysis for duration until RTW are presented in table 4. The ICER for sustainable RTW was 56 indicating that each day earlier RTW in the intervention group is associated with cost savings of €56 in comparison with the usual care group. In the CE plane, 69% of the incremental cost effect pairs were located in the south-east quadrant indicating that the intervention is more effective and less costly than usual care (figure 2A). The CEA curve presented in figure 2B shows that if the societal willingness-to-pay (WTP) for one earlier day of RTW is €0, the probability that the intervention is cost-effective in comparison with usual care is 0.79. This probability increases to 0.97 at maximum if the WTP is €76 per day earlier RTW.

Table 4.

Differences in pooled means costs and effects, ICERs and the distribution of incremental cost-effectiveness pairs around the quadrants of the CE planes (main analysis)

| Outcome | ∆ Cost* (€) mean (95% CI) | ∆ Effect* (days) mean (95% CI) | ICER €/day | Distribution CE plane | |||

| NE† (%) | SE‡ (%) | SW§ (%) | NW¶ (%) | ||||

| RTW | −228 (−708 to 136) | 4.1** (−2.6 to 10.8) | −56 | 15 | 69 | 10 | 6 |

| QALYs gained | −647 (−2116 to 735) | −0.001 (−0.023 to 0.020) | 501 187 | 4 | 42 | 35 | 19 |

| HR-QoL (SF-36) | |||||||

| PCS | −647 (−2116 to 735) | −0.7 (−2.6 to 1.1) | 870 | 6 | 19 | 58 | 17 |

| MCS | −647 (−2116 to 735) | −0.4 (−2.5 to 1.7) | 1573 | 10 | 33 | 44 | 13 |

| Recovery (RI-10) | −647 (−2116 to 735) | −0.6 (−2.0 to 0.9) | 1127 | 5 | 22 | 55 | 18 |

*Uncertainty estimated using bootstrapping and corrected for clustering by hospital and type of surgery.

†Refers to the north-east quadrant of the CE plane, indicating that the intervention care programme is more effective and more costly than usual care.

‡Refers to the south-east quadrant of the CE plane, indicating that the intervention care programme is more effective and less costly than usual care.

§Refers to the south-west quadrant of the CE plane, indicating that the intervention care programme is less effective and less costly than usual care.

¶Refers to the north-east quadrant of the CE plane, indicating that the intervention care programme is less effective and more costly than usual care.

**Note that a positive value indicates faster RTW in the intervention group compared with the control group.

CE, cost-effectiveness; HR-QoL, health-related quality of life; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; MCS, mental component scale; PCS, physical component scale; QALY, quality-adjusted life year; RI, recovery index; RTW, return to work; SF, short form.

Figure 2.

CE planes and CEA curves for RTW and QALYs. The CE planes indicate the uncertainty around the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio for RTW (A) and QALYs (C). The CEA curves indicate the probability of cost-effectiveness for different values (€) of willingness-to-pay per unit of effect gained for RTW (B) and QALYs (D). CE, cost-effectiveness; CEA, cost-effectiveness acceptability; QALY, quality-adjusted life year; RTW, return to work.

Cost-utility and other secondary outcomes

The difference in QALYs gained over 12 months between the two study groups was small and not statistically significant or clinically relevant (table 4). Therefore, the ICER for QALYs became extraordinarily large (half million Euros). In the CE plane, the majority of cost-effect pairs were located in the southern quadrants, indicating that the intervention was less expensive than usual care. However, the cost-effect pairs were roughly divided between the eastern and the western quadrant, indicating that the intervention can lead to both better and worse outcomes compared to usual care (figure 2C). As a result, the probability that the intervention was cost-effective for QALYs in comparison with usual care was considerably lower than for the primary outcome (0.77 at WTP is €0 per QALY gained and decreasing at higher WTP values) (figure 2D).

The differences observed for the secondary outcomes health-related quality of life and recovery at 12 months were also small and not significant, leading to a low probability of cost-effectiveness for these outcomes as well.

Per-protocol analysis

In the per-protocol analysis, 40 patients were excluded because they did not receive the care according to protocol due to several reasons: did not fit the inclusion criteria (n=3), had a more severe surgery than planned (n=25) or had a complicated postoperative course and needed a repeat surgery during follow-up (n=12). By excluding those patients, the difference in effect became larger, but was still not significant (−6.4 days, 95% CI −12.9 to 0.20), and the cost differences became statistically significant in favour of the intervention (mean difference €−359, 95% CI −866 to −11) (table 5). Hence, compared with the main analysis, the probability of cost-effectiveness increased considerably at a WTP of €0 per 1 day earlier RTW (from 0.79 to 0.92).

Table 5.

Results from the per-protocol and sensitivity analyses (RTW)

| Analysis | Sample size | ∆ Cost* (€) mean (95% CI) | ∆ Effect* (days) mean (95% CI) | ICER €/day |

Distribution CE plane | ||||

| IC | UC | NE† (%) | SE‡ (%) | SW§ (%) | NW¶ (%) | ||||

| Per-protocol analysis | 205 | 188 | −359 (−866 to −11) | 6.4** (−0.2 to 12.9) | −56 | 8 | 87 | 5 | 1 |

| Complete-case analysis | 154 | 150 | −45 (−466 to 362) | 11.6** (−5.4 to 19.3) | −4 | 45 | 55 | 0 | 0 |

| Friction cost approach | 227 | 206 | −228 (−708 to 136) | 4.1** (−2.6 to 10.8) | −56 | 15 | 69 | 10 | 6 |

| Healthcare perspective | 227 | 206 | −61 (−361 to 218) | 4.1** (−2.6 to 10.8) | −15 | 28 | 56 | 5 | 10 |

*Uncertainty estimated using bootstrapping and corrected for clustering by hospital and type of surgery.

†Refers to the north-east quadrant of the CE plane, indicating that the intervention care programme is more effective and more costly than usual care.

‡Refers to the south-east quadrant of the CE plane, indicating that the intervention care programme is more effective and less costly than usual care.

§Refers to the south-west quadrant of the CE plane, indicating that the intervention care programme is less effective and less costly than usual care.

¶Refers to the north-west quadrant of the CE plane, indicating that the intervention care programme is less effective and more costly than usual care.

**Note that a positive value indicates faster RTW in the intervention group compared with the control group.

CE, cost-effectiveness; IC, intervention care; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; RTW, return to work; UC, usual care.

Sensitivity analyses

The results of the primary outcome in the sensitivity analyses differed in some aspects from the main analysis (table 5). First, in the complete-case analysis, the effect difference between study groups became larger in favour of the intervention group, but the cost savings in the intervention group as compared with usual care became smaller. The probability of cost-effectiveness compared with the main analysis therefore decreased (from 0.79 to 0.55). Second, the results from the friction cost analysis were identical to the intention to treat analysis, indicating that the majority of patients returned to their work before the end of the friction period of 23 weeks. Finally, in the analyses performed from the healthcare perspective, cost savings became much smaller, as costs associated with lost productivity were not taken into account. As a result the probability of cost-effectiveness reduced (from 0.79 to 0.61).

The results of the per-protocol analyses and sensitivity analyses for the secondary outcomes QALYs, health-related quality of life and recovery are presented in online supplementary table 2. In the per-protocol analyses, cost differences became larger in favour of the intervention group, however, they did not reach statistical significance. The probability of cost-effectiveness at a WTP of €0 per unit of effect increased from 0.77 to 0.93. In contrast to the complete-case analysis for the primary outcome, the complete-case analyses for the secondary outcomes showed a statistical significant increase in cost savings in the intervention group. The probability of cost-effectiveness at a WTP of €0 per unit of effect increased from 0.77 to 0.98.

bmjopen-2017-017782supp002.pdf (232KB, pdf)

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the cost-effectiveness and cost-utility of a rigorously designed internet-based perioperative care programme compared with usual care for gynaecological patients. Our results show that for the primary outcome duration until full resumption of work, the probability that the care programme is cost-effective as compared with usual care is 0.97 at a WTP of €76 per day earlier RTW. Taking into account that the average costs per sick leave day are €230, we conclude that the intervention is cost-effective as compared with usual care.

Interpretation of the findings

In the current economic evaluation, the adjusted mean difference until RTW between study groups was not statistically significant (−4.1 days, 95% CI −10.8 to 2.6). In the accompanying paper on the clinical effectiveness of the intervention, median days until RTW were compared between study arms using Cox regression analyses.12 However, survival analysis results in difficulties in interpreting the ICER. Therefore, we chose to compare mean days until RTW in the current cost-effectiveness study and used bootstrapping to account for the skewed distribution of this variable.

In addition, the cost-difference between the intervention group and the control group was not statistically significant either, although total societal costs were lower in the intervention group than in the control group. A possible explanation might be that the sample size of this study was based on the primary outcome full sustainable RTW and, therefore, underpowered to detect relevant cost differences, as cost data are right skewed and require relative large samples.27

Secondary care costs in the intervention group were lower compared with the usual care group. Future research should investigate if the care programme truly leads to different health-seeking behaviour. Possibly, patients receiving additional perioperative care were more confident in their own self-management skills preventing them from visiting a healthcare professional. In addition, costs associated with primary care were similar in both groups, demonstrating that the care programme did not cause a shift from secondary care to primary care in the intervention group compared with the usual care group. Concerns of increased workload in the primary care setting due to changes in perioperative care have been reported before, however, seem to be ungrounded based on our results.28 29

We did not find any clinical relevant differences in the secondary outcomes. Thus, despite the possible difference in the RTW rates between study groups, this did not have an effect on patients’ perceptions about their quality of life and recovery. Possibly, the surgery itself has a much larger impact on these outcomes than the method of postoperative guidance.

The results of the per-protocol analyses were slightly more favourable towards the intervention programme than those of the main analyses. Thus, by presenting the intervention to the ideal target population, the probability of cost-effectiveness of the intervention in comparison with usual care increases. This is in concordance with our initial objective to develop an internet-based care programme for women undergoing an uncomplicated surgical procedure.10 It may be challenging to identify future patients who will benefit most from the care programme, as complications, generally, cannot be predicted preoperatively. In addition, it should be investigated further what the needs are of patients with a complicated course and how they should best be guided and monitored during their recovery.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

Several strengths of the present study are noteworthy. First of all, we are not aware of other current perioperative interventions that aim at preventing unnecessary prolonged recovery and reducing sick leave in order to contain societal costs associated with gynaecological surgical care. Second, analyses were performed alongside a pragmatic trial, allowing prospective collection of relevant cost and effect data and enabling the evaluation of the intervention’s cost-effectiveness under real-world conditions.27 The third strength concerns the use of linear multilevel analyses to account for possible clustering of data as a result of the chosen study design. Randomisation at cluster level was chosen to prevent contamination between the study arms. Moreover, the employment of a stepped-wedge design allowed the sequential implementation of the care programme in the participating hospitals, providing the possibility to study the implementation process as well.

Our study also has limitations. The first limitation is the collection of cost data through self-reported retrospective questionnaires. However, since administrative data on service use are very hard to obtain in the Netherlands, societal cost data can only be collected by means of self-report. In order to prevent recall-bias, we minimised the recall period to only 1 month. In addition, if there was recall bias, it seems unlikely that this systematically differed between the study groups. Therefore, we expect that this does not affect our estimations. A second limitation concerns the amount of incomplete data. Despite our efforts to obtain full data from the patients in the trial, only 70.4% of the study population had complete cost data. Although this is an acceptable rate of missing data, complete-case analyses may be biased and have less precision.30 31 We tried to account for this by applying multiple imputation for missing data.32 Comparison of participants with complete and incomplete data resulted in a number of variables that predicted the presence of missing data. Therefore, we concluded that the data was missing at random, making multiple imputation the appropriate method to deal with the missing data. Finally, it should be noted that a typical feature of internet-based interventions is the risk of selection bias towards the higher educated participant. Also in our study, included participants were employed women of which the majority was highly educated, and patients that were computer or internet illiterate were excluded. Therefore, caution is needed when generalising the findings, as clinical and cost-effectiveness may be reduced when the intervention is accessible for the general audience. Moreover, due to (cultural) differences in attitudes towards health and work as well as differences in the organisation of social and healthcare systems, generalisability of the results across countries might be hampered as well.

Comparison with other studies

We showed that costs associated with productivity loss following gynaecological surgery were about two times higher than healthcare costs. We are not aware of previously published literature in the gynaecological field in which this was demonstrated before. As a matter of fact, outcomes such as long-term convalescence, return to normal activities and absenteeism following gynaecological surgery are under-reported in clinical trials. In a review of Roumm et al assessing the clinical and economic benefits of minimal invasive surgery compared with open alternatives, only 5 of the 19 eligible studies reported data on RTW or return to normal activities, whereas 15 studies reported on hospital costs and all studies reported on length of stay.33 Similarly, in a recent Cochrane systematic review assessing the effectiveness and safety of different surgical approaches to hysterectomy in women with benign gynaecological disease, 45 of the 47 included studies reported on the length of postoperative hospital stay, and only 19 studies reported data on return to normal activities.34

Cost-effectiveness is one of the most frequently cited reasons for developing internet interventions because of the relative low delivery costs and the potential high impact.35 However, economic evaluations are mainly lacking. A recent systematic review that evaluated the effect of perioperative eHealth interventions on the postoperative course concluded that only 6 of 19 included studies reported on costs, and in only one study, a full economic evaluation was performed.36 Thus, the current study addresses this literature gap as well.

Policy implications and recommendations

Whether the perioperative internet-based care programme under study is considered cost-effective in comparison with usual care in accelerating RTW following gynaecological surgery depends on society’s WTP for a reduced sick leave day, as well as the probability of cost-effectiveness that is considered acceptable. Our results show that the probability of cost-effectiveness is 0.97 at a WTP of €76 per day earlier RTW. Considering that on average the costs of a day of sickness absence are €230,18 we expect that this intervention can be considered cost-effective in comparison with usual care.

A latent barrier to future acceptance and implementation of the care programme lies in the fact that the costs and benefits of the care programme are separated between different types of stakeholders. In the Netherlands, medical costs are paid by the government and health insurance companies and sickness benefits are the main responsibility of the employers, which make the shifting of costs across these sectors hard. As follows, investments are made in the healthcare sector for implementing the care programme and changing care processes, while the largest benefits accrue to employers through reduced lost productivity costs. However, many countries have an employer-provided health insurance (eg, the USA), and in those countries, this internet-based care programme is much more likely to be adapted as investments in the internet-based care programme may directly lead to savings through improved productivity rates.

Conclusions

The encouraging outcomes of this trial show that there is an economic case for supporting patients in the perioperative period with an internet-based care programme. The care programme has a potential to lead to societal cost savings as a result of a reduction in the duration until full sustainable RTW. If society is willing to pay €76 per day earlier RTW, the care programme is considered cost-effective in comparison with usual care in women undergoing benign gynaecological surgery. Policy-makers should investigate how these monetary benefits can be distributed across stakeholders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants of this trial. Derrick Stomp is thanked for his extensive role in developing the web portal. Dirk Knol is thanked for his statistical contributions in the earlier phases of this research. Arianne Scholten is thanked for her role in the recruitment of patients.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors made substantial contributions to this study and the article. EVAB, HAMB, JRA and JAFH participated in the design and/or execution of the study, the interpretation of data and the drafting and/or revision of the article. JEB and JMvD were involved in the statistical data analyses, interpretation of the data and revision of the article. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. EVAB and JAFH are the study guarantors.

Funding: This study is funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research and Development (ZonMw grants 171102015 and 92003590).

Competing interests: JRA reports a chair in Insurance Medicine paid by the Dutch Social Security Agency, and he is a stockholder of Evalua. JAFH reports grants from Samsung, Gideon Richter and Celonova outside the submitted work. HAMB reports grants from Olympus and personal fees from Nordic Farma during the conduct of the study. JRA and JAFH are planning to set up a spin-off company concerning the implementation of a mobile application concerning the ikherstel intervention in the Netherlands.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the VU University Medical Centre (16 May 2011, no 2011/142) and by the medical ethics committees of Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis Oost (Amsterdam), Meander Medical Center (Amersfoort), Amstelland Hospital (Amsterdam), Medical Center Alkmaar (Alkmaar), Diakonessenhuis (Utrecht), Spaarne Gasthuis (locations Haarlem and Hoofddorp) and Flevo Hospital (Almere).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available though details on statistical analyses are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

- 1.Cox H. Recovery from gynaecological day surgery: are we underestimating the process. Ambul Surg 2003;10:114–21. 10.1016/S0966-6532(03)00007-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horvath KJ. Postoperative recovery at home after ambulatory gynecologic laparoscopic surgery. J Perianesth Nurs 2003;18:324–34. 10.1016/S1089-9472(03)00181-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilmartin J. Contemporary day surgery: patients’ experience of discharge and recovery. J Clin Nurs 2007;16:1109–17. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01548.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evenson M, Payne D, Nygaard I. Recovery at home after major gynecologic surgery: how do our patients fare? Obstet Gynecol 2012;119:780–4. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824bb15e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. Am J Surg 2002;183:630–41. 10.1016/S0002-9610(02)00866-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kjølhede P, Borendal Wodlin N, Nilsson L, et al. . Impact of stress coping capacity on recovery from abdominal hysterectomy in a fast-track programme: a prospective longitudinal study. BJOG 2012;119:998–1007. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03342.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wodlin NB, Nilsson L. The development of fast-track principles in gynecological surgery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2013;92:17–27. 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01525.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naidu M, Sultan AH, Thakar R. Convalescence advice following gynaecological surgery. J Obstet Gynaecol 2012;32:556–9. 10.3109/01443615.2012.693983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouwsma EV, Anema JR, Vonk Noordegraaf A, et al. . The cost effectiveness of a tailored, web-based care program to enhance postoperative recovery in gynecologic patients in comparison with usual care: protocol of a stepped wedge cluster randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protoc 2014;3:e30 10.2196/resprot.3236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vonk Noordegraaf A, Huirne JA, Brölmann HA, et al. . Multidisciplinary convalescence recommendations after gynaecological surgery: a modified Delphi method among experts. BJOG 2011;118:1557–67. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03091.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vonk Noordegraaf A, Huirne JA, Pittens CA, et al. . eHealth program to empower patients in returning to normal activities and work after gynecological surgery: intervention mapping as a useful method for development. J Med Internet Res 2012;14:e124 10.2196/jmir.1915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bouwsma EVA, Huirne JAF, van de Ven PM, et al. . Effectiveness of an internet-based perioperative care programme to enhance postoperative recovery in gynaecological patients: cluster controlled trial with randomised stepped-wedge implementation. BMJ Open. In Press 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care 1997;35:1095–108. 10.1097/00005650-199711000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lamers LM, Stalmeier PF, McDonnell J, et al. . (Measuring the quality of life in economic evaluations: the Dutch EQ-5D tariff). Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2005;149:1574–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aaronson NK, Muller M, Cohen PD, et al. . Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 Health Survey in community and chronic disease populations. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1055–68. 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00097-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kluivers KB, Hendriks JC, Mol BW, et al. . Clinimetric properties of 3 instruments measuring postoperative recovery in a gynecologic surgical population. Surgery 2008;144:12–21. 10.1016/j.surg.2008.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frick KD. Microcosting quantity data collection methods. Med Care 2009;47:S76–S81. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819bc064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Tan S, Bouwmans C. Handleiding voor kostenonderzoek methoden en standaard kostprijzen voor economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg. Tijdschrift voor gezondheidswetenschappen 2010;90:367–72. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Z-index. G-Standaard. Z-index. 2014. http://www.webcitation.org/6NnSqbHJW.

- 20.Koopmanschap MA. PRODISQ: a modular questionnaire on productivity and disease for economic evaluation studies. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2005;5:23–8. 10.1586/14737167.5.1.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Dongen JM, van Wier MF, Tompa E, et al. . Trial-based economic evaluations in occupational health: principles, methods, and recommendations. J Occup Environ Med 2014;56:563–72. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, et al. . Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 3rd edn New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med 2011;30:377–99. 10.1002/sim.4067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Efron B, Data M. Imputation, and the bootstrap. J Am Stat Assoc 2012;89:463–75. [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Leeden R : Leeuw J, Meijer E, Resampling multilevel models. handbook of multilevel analysis. New York, NY: Springer Science, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petrou S, Gray A. Economic evaluation alongside randomised controlled trials: design, conduct, analysis, and reporting. BMJ 2011;342:d1548 10.1136/bmj.d1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bailey J, Roland M, Roberts C. Is follow up by specialists routinely needed after elective surgery? A controlled trial. J Epidemiol Community Health 1999;53:118–24. 10.1136/jech.53.2.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Easton K, Read MD, Woodman NM. Influence of early discharge after hysterectomy on patient outcome and GP workloads. J Obstet Gynaecol 2003;23:271–5. 10.1080/014436100000100088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burton A, Billingham LJ, Bryan S. Cost-effectiveness in clinical trials: using multiple imputation to deal with incomplete cost data. Clin Trials 2007;4:154–61. 10.1177/1740774507076914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacNeil Vroomen J, Eekhout I, Dijkgraaf MG, et al. . Multiple imputation strategies for zero-inflated cost data in economic evaluations: which method works best? Eur J Health Econ 2016;17:939–50. 10.1007/s10198-015-0734-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Briggs A, Clark T, Wolstenholme J, et al. . Missing…presumed at random: cost-analysis of incomplete data. Health Econ 2003;12:377–92. 10.1002/hec.766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roumm AR, Pizzi L, Goldfarb NI, et al. . Minimally invasive: minimally reimbursed? An examination of six laparoscopic surgical procedures. Surg Innov 2005;12:261–87. 10.1177/155335060501200313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aarts JW, Nieboer TE, Johnson N, et al. . Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;8:CD003677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tate DF, Finkelstein EA, Khavjou O, et al. . Cost effectiveness of internet interventions: review and recommendations. Ann Behav Med 2009;38:40–5. 10.1007/s12160-009-9131-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van der Meij E, Anema JR, Otten RH, et al. . The effect of perioperative e-health interventions on the postoperative course: a systematic review of randomised and non-randomised controlled trials. PLoS One 2016;11:e0158612 10.1371/journal.pone.0158612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-017782supp001.pdf (240.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-017782supp002.pdf (232KB, pdf)