Abstract

Objectives

To find determining factors for persistent infarction signs in patients with transient ischaemic attack (TIA), herein initial diffusion lesion size, visibility on apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) or fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) and location.

Design

Prospective cohort study of patients with clinical TIA receiving 3T-MRI within 72 hours of symptom onset and at 8-week follow-up.

Setting

Clinical workflow in a single tertiary stroke centre between February 2012 and June 2014.

Participants

199 candidate patients were recruited, 64 patients were excluded due to non-TIA discharge diagnosis or no 8-week MRI. 122 patients completed the study.

Primary outcome measures

The primary outcome was visible persistent infarction defined as 8-week FLAIR hyperintensity or atrophy corresponding to the initial diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) lesion.

Results

50 patients showed 84 initial DWI lesions. 29 (35%) DWI lesions did not result in infarction signs on 8-week FLAIR. 26 (90%, P<0.0001) reversing lesions were located in the cortical grey matter (cGM). cGM location (vs any other location) strongly predicted no 8-week infarction sign development (OR 0.02, 95% CI 0.001 to 0.17) or partial lesion area decrease (>30% of initial DWI-area, OR 14.10, 95% CI 3.61 to 54.72), adjusted for FLAIR-visibility, DWI-area, ADC-confirmation and time to scan (TTS) from symptom onset to baseline MRI. Acute FLAIR-visibility was a strong associated factor for persistent infarction signs (OR 33.06, 95% CI 2.94 to 1432.34). For cGM lesions area size was sole associated factor for persistent infarction signs with a 0.31 cm2 (area under the curve (AUC), 0.97) threshold. In eight (16%) DWI-positive patients, all lesions reversed fully.

Conclusions

16% of DWI-positive patients and one-third of acute DWI lesions caused no persistent infarction signs, especially small cGM lesions were not followed by development of persistent infarction signs. Late MRI after TIA is likely to be less useful in the clinical setting, and it is dubious if the absence of old vascular lesions can be taken as evidence of no prior ischaemic attacks.

Trial registration number

NCT01531946; Results.

Keywords: transient ischemic attack, cerebral cortex, brain infarction, cerebral circulation, magnetic resonance imaging

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Prospective inclusion cohort study of patients with clinical transient ischaemic attack evaluated by senior consultant stroke neurologists.

Patients received standardised baseline and 8-week follow-up MRI in clinical workflow.

National electronic registers provided long-term follow-up.

Small lesions below 3 mm were included as they are associated with increased risk of stroke and death.

Main limitations are sequence resolution and small lesion size.

Introduction

The risk of recurrent events including devastating stroke after transient ischaemic attack (TIA) remains substantial.1 2 Recently, it was shown that the presence of a diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) lesion combined with clinical findings enhanced prediction of post-TIA stroke risk compared with clinical findings alone.3–5 Even small vascular brain lesions below 3 mm were associated with increased risk of stroke and death.6 In patients with TIA, DWI lesions are reported in 25%–50%.4 5 7–11 Also, the time to baseline MRI varies from within 24 hours to 3 weeks from symptom onset.12 A recent meta-analysis found that the up to sevenfold variation in DWI-positivity rates in patients with clinical TIA remains largely unexplained despite attempts to control for factors as varying time to MRI.12 Among patients with clinical ischaemic stroke, one-third is DWI-negative, but their long-term outcome and recurrence rates did not differ from DWI-positive patients.13

Pioneering studies found that patients with apparent DWI lesion reversal had shorter symptom duration than patients with persistent infarction signs14 and noted absence of persistent infarction signs in a fraction of initially DWI-positive patients on chronic phase MRI.14 15 Lesions with persistent infarction signs were larger and had lower apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values.15 A recent series of mixed TIA and minor stroke patients found only 6% of initially DWI-positive patients showed no lesion on T2-fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images obtained 1–3 months later.16 Despite small numbers the absent lesions seemed primarily located in cortical grey matter (cGM),16 suggesting that acute DWI reversal may be related to the proximity of leptomeningeal collaterals.17 18 Cortical perfusion is higher than white matter (WM) perfusion, even though the ratio declines with age.19 The impact of the underlying vascularity is also highlighted in a perfusion study of initially DWI-negative patients with clinical time-based TIA. Patients with initial focal or territorial perfusion abnormalities showed increased rates of new DWI lesions on 3-day follow-up compared with patients with no perfusion abnormalities.20 Animal imaging studies of transient ischaemia with subcortical DWI lesion have shown apparent 10-week T1-signal and T2-signal normalisation while histology showed selective neuronal loss and gliosis.21 Persistent signal changes most likely correspond to pannecrosis. A recent 7T in vivo human study showed the presence of likely cortical microinfarcts with similar MRI appearance compared with microinfarcts on ex vivo brain slices with histopathological correlate.22 Although the clinical significance of persistent infarction signs is unclear, it is well known that numerous cerebral infarcts gathered over time are predictive of poor outcome6 and cognitive decline,23 rendering it of potential pathophysiological and clinical importance to investigate what determines the formation of persistent infarction signs. Clinical MRI may not be able to detect all acute or chronic ischaemic changes13; yet DWI and T2-FLAIR are the most commonly used tools for ischaemia assessment.24 We hypothesised that lesion size, ischaemic depth and location are factors likely to predict the occurrence of infarction signs after acute ischaemia in clinical TIA.

We aimed to investigate in a clinical setting which characteristics were associated with persistent infarction signs 8 weeks after DWI-positive TIA, including lesion location, size, initial ADC and FLAIR visibility, TIA aetiology and clinical risk factors. The ultimate aim was to establish if no development of persistent infarction signs after DWI-positive TIA occurred with a clinically significant frequency.

Methods

We investigated a prospective patient cohort with clinical TIA included after informed consent.

Clinical methodology

We included patients with TIA or minor stroke defined as an episode of acute focal neurological symptoms of vascular origin25 with resolution within 24 hours.26 We defined resolution as National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score of 0 within 24 hours. Senior consultant stroke neurologists clinically evaluated and included patients with a history and clinical findings consistent with TIA February 2012–June 2014. Exclusion criteria were TIA (G45.9) not final clinical diagnosis, thrombolysis treatment, MRI contraindications and severe illness likely to preclude follow-up. Definitions of clinical risk factors are presented in online supplementary methodology. Risk factors of stroke, ABCD227 and Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST)28 classification were recorded. All patients were treated with antithrombotics and other pharmacological secondary prevention according to guidelines.

bmjopen-2017-018160supp001.pdf (515.2KB, pdf)

MR imaging

We performed 3T-MRI (Siemens Magnetom Verio, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with a 32-channel head coil (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) including DWI and T2-FLAIR imaging after routine stroke protocol within 72 hours from symptom onset29 and at 8-week follow-up to visualise persistent infarction signs. The diffusion protocol was single-shot spin-echo diffusion echo planar imaging with 220 mm field of view (FOV), 254 mm axial 0 mm gap slices, b-value 1000 s/mm2 along three orthogonal directions; TR/TE 6600/100 ms, acceleration factor R 2, matrix size 192×192. The T2-FLAIR protocol was 240 mm FOV, 274 mm axial 0 mm gap slices, TR/TE 6500/133 ms, TI 2134 ms, acceleration factor R 2, matrix size 256×256.

Image reading was performed as visual inspection in a clinical setting using the PACS without external software. Image analysis had two steps: first, we created an image template consisting of literature-based examples of the scoring categories employed and a case report form (CRF). Two blinded certified consultant neuroradiologists (IH, AFC) tested template and CRF on 50 randomly chosen cases from the cohort, reading first independently, followed by a joined re-evaluation of the cases. A consensus-based use of the reading tools was thus achieved enabling the use of one reader for consistence and reproducibility in assessing the often small lesions. Subsequently, one reader (IH), blinded to clinical data except for the referral, systematically evaluated the cohort’s scans.

In a random 10% sample (defined by date of birth as 4th, 14th and 24th day in any month), we calculated Cohen’s kappa for intraobserver variation using two CRF readings, except for area measurements, with 3 months interval and observed a substantial intraobserver agreement (κ=0.80).

Definitions of post hoc vascular findings are presented in online supplementary methodology.

Definitions of lesions, size and localisation

We used coregistration marking each lesion with two perpendicular intrathecal diameters to ascertain lesion localisation between sequences and baseline and 8-week MRI. Two separate lesions must not have confluent gliosis. As proxy for lesion size, we used largest lesion area on one slice measured by manual regions of interest (ROIs).30 On baseline MRI, we scored for presence or absence of DWI lesions, ADC-confirmation and T2-FLAIR hyperintensities, and divided lesion localisation into WM, cGM and deep grey matter (dGM) (basal ganglia). cGM lesions may have a minor subcortical WM component.

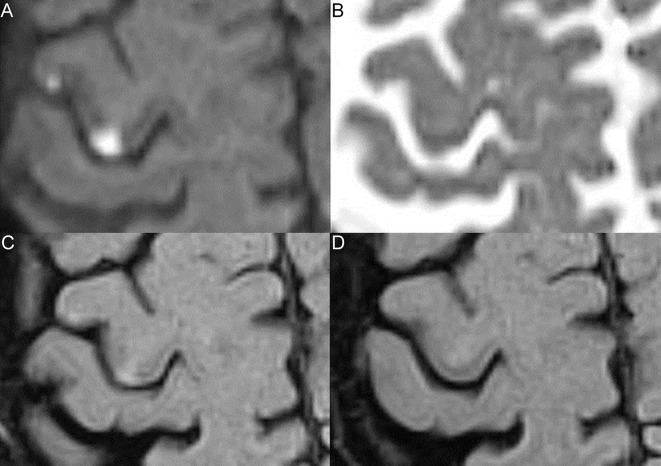

We defined persistent infarction signs as presence of T2-FLAIR hyperintensity24 31 or atrophy in the initial DWI-lesion area on 8-week MRI.15 16 32 Absence of 8-week T2-FLAIR hyperintensity or atrophy in the initial DWI-lesion area was defined as no persistent infarction signs (figure 1); lesion area decrease was defined as 30% or more lesion area reduction. Due to small lesion size, this definition was modified from the 10% reduction used in ischaemic stroke.33 Lesion area change was graded at 30%, 50% and 100%.

Figure 1.

Lesions with and without 8-week infarction signs. Two cortical grey matter lesions are shown on initial diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) (A), apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) (B), initial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) (C) and 8-week FLAIR (D). (A) Both lesions are DWI-positive. (B) The medial lesion is ADC-confirmed, the lateral lesion shows no ADC-confirmation. (C) Both lesions are initially FLAIR-positive. (D) The medial lesion is 8-week FLAIR-positive, the lateral lesion is 8-week FLAIR-negative.

After collecting all initial and 8-week clinical and radiological data, we checked if DWI lesion site and symptoms matched—which it did in all cases—under the supervision of a senior stroke consultant (HC).

Recurrence and follow-up

All patients had a scheduled 8-week telephone follow-up34 35 by a doctor to assess self-reported functional status and recurrence of new stroke or TIA. Standard 3-month follow-up was a face-to-face interview with a trained nurse assessing functional status, changes in risk factor status and medication adherence. National electronic patient files provided long-term follow-up information on new vascular events.

Statistics

For categorical data, we used Fisher’s exact test and Mann-Whitney U test for population comparison. For dichotomised outcomes, we performed a general linear model-based forced entry logistic regression analysis; P values were calculated with the Wald test. We included lesion location, DWI-lesion size (cm2), visibility on baseline ADC or FLAIR and time to baseline MRI as parameters in the multivariate analysis. We performed a likelihood ratio test for model fit versus an empty model. We used receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis for binary classification. Recurrent cerebrovascular events were studied using Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox Proportional Hazard Model. We considered P values less than 0.05 significant. We used R (V.3.2.0), 2015 The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, URL: http://www.R-project.org/ and SPSS (V.22.0) statistical software, IBM.

Results

We included 122 patients with clinical TIA (figure 2), median (IQR) age of 65 (54–71) years and median (IQR) ABCD2 4 (3–5) (table 1). The median (IQR) time from ictus to initial MRI (TTS) was 31.5 (23.5–56.8) hours. Table 1 shows the patients’ baseline characteristics and findings on subacute DWI and 8-week T2-FLAIR. Fifty patients showed 84 DWI lesions. Thirty-two patients had solitary DWI lesions. Thirty-three lesions were located in WM, 47 lesions in cGM and 4 lesions in dGM. There were no statistically significant relations between DWI-positivity rates and time to scan.

Figure 2.

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology diagram of patient flow, inclusion and exclusion. Other non-ischaemic comprises patients with peripheral nerve compression (2), ophthalmological symptoms (2), trigeminal neuralgia (1), normal pressure hydrocephalus (1), hyperventilation (1), paraesthesia secondary to anaemia (1), peripheral extremity embolus (1), food poisoning (1) and secondary refusal (1). TIA, transient ischaemic attack; tPA, tissue plasminogen activator.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| All 8 weeks | Eight-week infarct | No infarct | P | OR (95% CI) | |

| All patients | 122 | 43 | 79 | ||

| Female sex, n | 52 (43%) | 15 (35%) | 37 (47%) | 0.251* | 0.61 (0.28 to 1.31) |

| Age, median (IQR) | 65 (54–71) | 60 (53–70) | 65 (55–74) | 0.228† | – |

| Medical history | |||||

| Prior stroke | 22 (18%) | 6 (14%) | 16 (20%) | 0.466* | 0.64 (0.23 to 1.78) |

| Prior TIA | 12 (10%) | 7 (16%) | 5 (6%) | 0.111* | 2.87 (0.85 to 9.70) |

| Prior MI | 9 (7%) | 2 (5%) | 7 (9%) | 0.491* | 0.50 (0.10 to 2.53) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 12 (10%) | 7 (16%) | 5 (6%) | 0.111* | 2.89 (0.85 to 9.70) |

| Hypertension | 60 (49%) | 26 (60%) | 34 (43%) | 0.088* | 2.02 (0.95 to 4.31) |

| Diabetes | 16 (13%) | 8 (19%) | 8 (10%) | 0.261* | 2.03 (0.70 to 5.86) |

| Depression | 14 (11%) | 7 (16%) | 7 (9%) | 0.244* | 2.00 (0.65 to 6.14) |

| Current smoking | 43 (35%) | 18 (42%) | 25 (32%) | 0.324* | 1.53 (0.71 to 3.30) |

| Alcohol overuse | 12 (10%) | 5 (12%) | 7 (9%) | 0.754* | 1.32 (0.39 to 4.43) |

| Antiplatelet use | 40 (33%) | 13 (30%) | 27 (34%) | 0.692* | 0.84 (0.38 to 1.86) |

| Warfarin | 2 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 1.000* | 1.86 (0.11 to 30.5) |

| Index TIA | |||||

| ABCD2 | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | 0.485† | – |

| Symptom duration | 0.852* | ||||

| <60 min | 58 | 21 (36%) | 37 (64%) | 1.00 | |

| >60 min | 64 | 22 (34%) | 42 (66%) | 0.93 (0.44 to 1.94) | |

| Imaging findings | |||||

| TTS (hours) | 32 (24–57) | 41 (22–66) | 29 (24–50) | 0.367† | – |

| DWI-positive | 50 | 42 (84%) | 8 (16%) | <0.0001* | NA |

| Sum of DWI-lesion area, cm2 | 0.41 (0.21–1.08) | 0.53 (0.31–1.22) | 0.09 (0.07–0.22) | <0.0001† | – |

| Ipsilateral cervical carotid stenosis | 5 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 4 (5%) | 0.656* | 0.45 (0.05 to 4.13) |

| Contralateral cervical carotid stenosis | 6 (5%) | 1 (2%) | 5 (6%) | 0.522* | 0.35 (0.04 to 3.12) |

| Ipsilateral intracranial stenosis‡ | 9 (12%) | 1 (4%) | 8 (17%) | 0.144* | 0.19 (0.02 to 1.63) |

| Contralateral intracranial stenosis‡ | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 0.450* | NA |

| TOAST aetiology | 0.727* | ||||

| Small vessels | 49 | 16 (33%) | 33 (67%) | 1.00 | |

| Large vessels | 28 | 12 (43%) | 16 (7%) | 1.55 (0.59 to 4.03) | |

| Cardiogenic | 18 | 5 (28%) | 13 (72%) | 0.79 (0.24 to 2.61) | |

| Multiple possible aetiologies | 27 | 10 (37%) | 17 (63%) | 1.21 (0.45 to 3.24) | |

| TTF (days) | 56 (55–60) | 55 (55–60) | 56 (55–60) | 0.832† | – |

*Fisher’s exact test.

†Mann-Whitney U test.

‡CTA or TCD available in 75 patients, hereof 28 with 8-week infarction signs.

CTA, CT angiography; DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; MI, myocardial infarction; NA, not applicable; TCD, transcranial Doppler; TIA, transient ischaemic attack; TOAST, Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment; TTF, time to follow-up; TTS, time to scan.

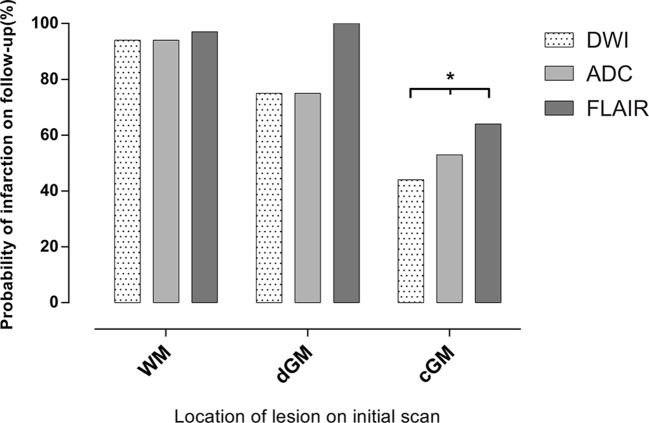

Initial DWI lesions located in cGM were less likely to show subsequent infarction signs on 8-week MRI (P<0.001, OR 0.07, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.27) compared with other locations. This finding persisted when including only ADC-confirmed lesions (22 with no persistent infarction signs, hereof 19 (86%) in cGM, P<0.001), or only lesions with subacute FLAIR-visibility (13 with no persistent infarction signs, hereof 12 (92%) in cGM, P<0.001, figure 3). Lesions with persistent infarction signs were significantly larger than lesions with no persistent infarction signs; DWI lesions leading to permanent infarction signs ranged 0.05–5.88 cm2 with median (IQR) 0.40 (0.13–0.86) cm2 and lesions with no permanent infarction signs ranged 0.03–1.10 cm2 with median 0.16 (0.08–0.22) cm2, P<0.001 (online supplementary table 1). In multivariate analysis, cGM location (cGM vs other locations), strongly predicted no persistent infarction signs (OR 0.02, 95% CI 0.001 to 0.17), whereas initial FLAIR-visibility predicted subsequent infarction signs (OR 33.06, 95% CI 2.94 to 1432.34). Initial DWI-lesion size, ADC-confirmation and TTS did not reach significance.

Figure 3.

Probability of permanent infarction signs stratified by anatomical location. DWI-lesion location in the cortical grey matter was significantly less likely to show permanent infarction signs. *P<0.001 against other anatomical location. ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; cGM, cortical grey matter; dGM, deep grey matter; DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; FLAIR, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; WM, white matter.

If the initial DWI lesion was located in cGM, no initial FLAIR-negative or ADC-negative lesions resulted in persistent infarction signs, but persistent infarcts were visible for 64% (21/33) of initially FLAIR-positive and 53% (21/40) of ADC-confirmed cGM lesions. Size of cGM lesions was the single associated factor for persistent infarction signs with an optimal area threshold 0.31 cm2 (AUC 0.97, online supplementary figure 1) to discern between lesions with or without 8-week infarction signs.

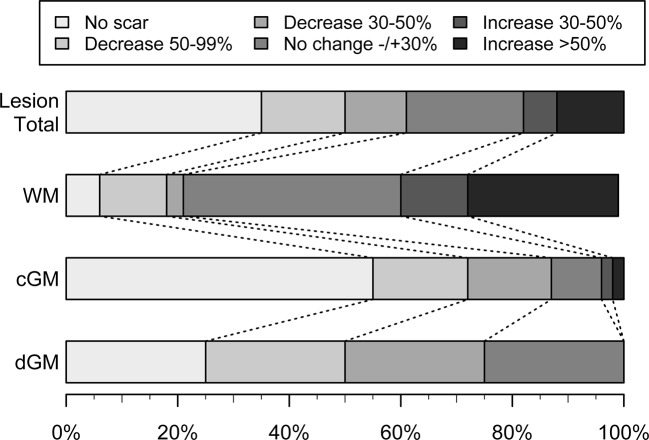

Figure 4 shows change of lesion size between baseline and 8-week MRI stratified according to tissue type. Of the initial 84 DWI lesions, 51 (61%) lesions showed at least 30% lesion area decrease and 15 (18%) showed lesion area increase of 30% or more. WM lesions had the highest rate of area increase, 13/33 (39%) and the highest degree of increase. We found that 41/47 (87%) of the lesions located in cGM decreased in size and 26/47 (55%) completely vanished leaving no persistent infarction signs (figure 4). Adjusted for ADC-confirmation, initial FLAIR-visibility and DWI-lesion size cGM location (cGM vs other locations) was a strong associated factor of lesion area decrease (OR 14.1, 95% CI 3.61 to 54.72). The distribution of lesions with area decrease or increase differed significantly between cGM and WM (P<0.0001, online supplementary figure 2).

Figure 4.

Decrease and increase of lesion size between admission MRI and 8-week follow-up MRI for all lesions and stratified according to lesion localisation into white matter (WM), cortical grey matter (cGM) and deep grey matter (dGM).

To assess if individual patients retain persistent infarction signs after having at least one DWI-positive lesion, we defined lesion burden as the sum of each patient’s combined DWI areas. Sixteen per cent of DWI-positive patients showed no persistent infarction signs (table 1). Only the combined sum of DWI-lesion areas significantly predicted persistent infarction signs. There was a significant correlation (OR 1.20 per additional mm2, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.28) between the patients’ total DWI area and the probability of persistent infarction signs. There was no significant correlation between increasing ABCD2 score and the probability of persistent infarction signs (OR 1.09, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.46).

Eight weeks post-TIA we found no correlation between persistent infarction sign presence and patient-reported return to pre-TIA daily activity level (4 (33%) vs 35 (36%), P=0.87). Fourteen recurrent cerebrovascular events occurred during the median (IQR) follow-up period of 817 (440–1056) days. Characteristics of patients with recurrent ischaemic event are presented in online supplementary table 2. Ipsilateral carotid stenosis ≥70% (HR 7.11, 95% CI 1.98 to 25.5) and several competing TOAST aetiologies (HR 3.74, 95% CI 1.13 to 12.4) predicted recurrent ischaemic events (online supplementary figure 3). Persistent 8-week infarction signs (HR 0.50, 95% CI 0.14 to 1.78) did not increase the risk of recurrent events.

Discussion

Sixteen per cent of initially DWI-positive patients and one-third of identified lesions show no sign of infarction 8 weeks later; cGM location was the strongest associated factor of full recovery on MRI at 8 weeks, and cGM DWI lesions smaller than 0.31 cm2 did not show persistent infarction signs. ADC confirmation or subacute FLAIR visibility did not in all cases result in visible long-term infarction signs.

Ischaemic lesions decreased in size after early intra-arterial revascularisation17 and cortical lesion sparing in middle cerebral artery territory infarctions was related to collateral perfusion and affected by significant stenosis of the ipsilateral anterior or posterior cerebral artery.18 In rats early (within 1 day) postischaemic maximum hyperperfusion indicated small final lesion size while rats with late (4 days) maximum hyperperfusion showed large lesions after transient experimental ischaemia,36 indicating rich, tightly webbed collaterals lead to improved early reperfusion and limit tissue damage.

Literature holds few and heterogeneous serial MRI TIA-related studies with varying populations and rates of DWI positivity and reversal. The mixed ‘high-risk TIA’16 and minor stroke study reported a 6% DWI-lesion reversal with imaging performed at a median delay of 13 hours after symptom onset. Our cohort only consists of patients with symptom duration of less than 24 hours, which may explain our larger 16% rate of patients with no persistent infarction signs. Our TTS and per patient DWI positivity and reversal rates correspond to the smaller time-based TIA study.15 Our cohort’s 31 hours median delay to imaging may explain why several lesions are FLAIR-positive representing the beginning vasogenic oedema, and the persistent ADC-reduction represents the still active cytotoxic oedema.37 We found no association between DWI-positivity rate and time to scan in line with recent meta-analysis.12

In TIA, DWI lesions are rarer and smaller and the TIA presumably results from smaller occlusive events compared with stroke. Changes in perfusion and underlying vascularity reflect tissue vulnerability and damage. This study indicates that ischaemic tissue damage in TIA is heterogeneous and differs with lesion localisation, which may mirror the inherent difference between end-artery dominated WM and cGM with proximity to leptomeningeal collaterals. This and smaller lesion size may explain the high variation in DWI-positivity rates among TIA populations and the high rate and cortical predilection of apparent diffusion lesion reversal in this TIA study.

However, in an observational exploratory study, we cannot infer causality but hypothesise that the stronger leptomeningeal collateral circulation in cGM may prevent persistent infarction signs in small lesions.

This study has some limitations. As inclusion was based on informed consent, the study was not unselected or consecutive. Fourteen per cent (12/84) of the initial lesions were small (<3 mm), and below the usual recommended cut-off level to discriminate between lacunes and perivascular spaces,38 but we included this type of lesion as it has been associated with increased risk of stroke and death.6 Other potential limitations are partial volume effects and the 2D-FLAIR sequence in our standard stroke MRI-protocol, though its slice thickness is similar to prior studies’.15 16Artefacts on T2-FLAIR caused by magnetic susceptibility, pulsatile CSF flow or no nulling of the CSF signal are common39 and may have masked small lesions. Other potential confounders are change and variation in FLAIR signal intensity of the lesion40 and our lesion definition includes atrophy corresponding to the initial DWI lesions although this can be difficult to visualise, even when aided by T1 and T2, and may explain why lesions are not persistently visible.15 32 We lost 10% (13/135) of eligible patients for 8-week MRI, this may have caused a selection bias. At 3T dedicated high-resolution 3D-FLAIR and 3D-T1 could improve differentiation between healthy tissue and postinfarction gliosis or atrophy, especially cortically. While probably not in clinical reach soon, higher field strength has shown promising results for the in vivo identification of cortical microinfarcts22 and visualised a hereto unseen but probably quite common structural ischaemic burden.

Conclusion

cGM localisation of the acute DWI lesion in TIA was a strong associated factor of no persistent infarction signs after TIA. Late MRI after TIA may not detect a significant number of lesions, especially cortical lesions and no prior lesions on the MRI is not evidence of no prior ischaemic events. It is yet to be determined if the apparent full resolution of brain lesions is related to the clinical course including risk of recurrence and sequelae of TIA including vascular dementia, fatigue and depression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

None

Footnotes

Contributors: IH, HC and AC conceived and designed the study. All authors were involved in data acquisition. KÆ, JM, PM, SR, MNF and HC were involved in patient inclusion. LW and CO performed telephone follow-up. IH, CO, JDN, AC and HC analysed and interpreted the data. IH wrote the first draft. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: CO holds research grants from the Velux-foundation, Bispebjerg University Hospital, University of Copenhagen, Axel Muusfeldts Foundation and Danish Medical Association. None of these were designated for this study.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Danish National Committee of Biomedical Research Ethics (H-1-2011-75).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Dataset are available upon publication from FigShare, DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.5091904.

References

- 1.Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, et al. . Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet 2007;369:283–92. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60150-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amarenco P, Lavallée PC, Labreuche J, et al. . One-year risk of stroke after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1533–42. 10.1056/NEJMoa1412981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coutts SB, Eliasziw M, Hill MD, et al. . An improved scoring system for identifying patients at high early risk of stroke and functional impairment after an acute transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. Int J Stroke 2008;3:3–10. 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2008.00182.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ay H, Arsava EM, Johnston SC, et al. . Clinical- and imaging-based prediction of stroke risk after transient ischemic attack: the CIP model. Stroke 2009;40:181–6. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.521476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merwick A, Albers GW, Amarenco P, et al. . Addition of brain and carotid imaging to the ABCD² score to identify patients at early risk of stroke after transient ischaemic attack: a multicentre observational study. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:1060–9. 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70240-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Windham BG, Deere B, Griswold ME, et al. . Small brain lesions and incident stroke and mortality: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:22–31. 10.7326/M14-2057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaharchuk G, Olivot JM, Fischbein NJ, et al. . Arterial spin labeling imaging findings in transient ischemic attack patients: comparison with diffusion- and bolus perfusion-weighted imaging. Cerebrovasc Dis 2012;34:221–8. 10.1159/000339682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleinman JT, Zaharchuk G, Mlynash M, et al. . Automated perfusion imaging for the evaluation of transient ischemic attack. Stroke 2012;43:1556–60. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.644971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mlynash M, Olivot JM, Tong DC, et al. . Yield of combined perfusion and diffusion MR imaging in hemispheric TIA. Neurology 2009;72:1127–33. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000340983.00152.69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Purroy F, Begué R, Quílez A, et al. . The California, ABCD and unified ABCD2 risk scores and the presence of acute ischemic lesions on diffusion-weighted imaging in TIA patients. Stroke 2009;40:2229–32. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.537969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giles MF, Albers GW, Amarenco P, et al. . Early stroke risk and ABCD2 score performance in tissue- vs time-defined TIA: a multicenter study. Neurology 2011;77:1222–8. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182309f91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brazzelli M, Chappell FM, Miranda H, et al. . Diffusion-weighted imaging and diagnosis of transient ischemic attack. Ann Neurol 2014;75:67–76. 10.1002/ana.24026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makin SD, Doubal FN, Dennis MS, et al. . Clinically Confirmed Stroke With Negative Diffusion-Weighted Imaging Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Longitudinal Study of Clinical Outcomes, Stroke Recurrence, and Systematic Review. Stroke 2015;46:3142–8. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kidwell CS, Alger JR, Di Salle F, et al. . Diffusion MRI in patients with transient ischemic attacks. Stroke 1999;30:1174–80. 10.1161/01.STR.30.6.1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oppenheim C, Lamy C, Touzé E, et al. . Do transient ischemic attacks with diffusion-weighted imaging abnormalities correspond to brain infarctions? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006;27:1782–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asdaghi N, Campbell BC, Butcher KS, et al. . DWI reversal is associated with small infarct volume in patients with TIA and minor stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014;35:660–6. 10.3174/ajnr.A3733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kidwell CS, Saver JL, Mattiello J, et al. . Thrombolytic reversal of acute human cerebral ischemic injury shown by diffusion/perfusion magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol 2000;47:462–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho HJ, Yang JH, Jung YH, et al. . Cortex-sparing infarctions in patients with occlusion of the middle cerebral artery. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010;81:859–63. 10.1136/jnnp.2009.195842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parkes LM, Rashid W, Chard DT, et al. . Normal cerebral perfusion measurements using arterial spin labeling: reproducibility, stability, and age and gender effects. Magn Reson Med 2004;51:736–43. 10.1002/mrm.20023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee SH, Nah HW, Kim BJ, et al. . Role of perfusion-weighted imaging in a diffusion-weighted-imaging-negative transient ischemic attack. J Clin Neurol 2017;13:129–37. 10.3988/jcn.2017.13.2.129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wegener S, Weber R, Ramos-Cabrer P, et al. . Temporal profile of T2-weighted MRI distinguishes between pannecrosis and selective neuronal death after transient focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2006;26:38–47. 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Veluw SJ, Zwanenburg JJ, Engelen-Lee J, et al. . In vivo detection of cerebral cortical microinfarcts with high-resolution 7T MRI. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013;33:322–9. 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Troncoso JC, Zonderman AB, Resnick SM, et al. . Effect of infarcts on dementia in the Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. Ann Neurol 2008;64:168–76. 10.1002/ana.21413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farr TD, Wegener S. Use of magnetic resonance imaging to predict outcome after stroke: a review of experimental and clinical evidence. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2010;30:703–17. 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Easton JD, Saver JL, Albers GW, et al. . Definition and evaluation of transient ischemic attack: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and the Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this statement as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke 2009;40:2276–93. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.192218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Anon. Special report from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Classification of cerebrovascular diseases III. Stroke 1990;21:637–76. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.192218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnston SC, Sidney S, Bernstein AL, et al. . A comparison of risk factors for recurrent TIA and stroke in patients diagnosed with TIA. Neurology 2003;60:280–5. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000042780.64786.EF [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adams HP, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, et al. . Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke 1993;24:35–41. 10.1161/01.STR.24.1.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions (UK). Stroke national clinical guideline for diagnosis and initial management of acute stroke and Transient Ischaemic Attack (TIA). London, UK: Royal College of Physicians (UK), 2008. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53287/ (accessed 13 Jan 2017). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cauley KA, Thangasamy S, Dundamadappa SK. Improved image quality and detection of small cerebral infarctions with diffusion-tensor trace imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013;200:1327–33. 10.2214/AJR.12.9816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harston GW, Minks D, Sheerin F, et al. . Optimizing image registration and infarct definition in stroke research. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2017;4:166–74. 10.1002/acn3.388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rovira A, Rovira-Gols A, Pedraza S, et al. . Diffusion-weighted MR imaging in the acute phase of transient ischemic attacks. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2002;23:77–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kranz PG, Eastwood JD. Does diffusion-weighted imaging represent the ischemic core? An evidence-based systematic review. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2009;30:1206–12. 10.3174/ajnr.A1547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merino JG, Lattimore SU, Warach S. Telephone assessment of stroke outcome is reliable. Stroke 2005;36:232–3. 10.1161/01.STR.0000153055.43138.2f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baggio JA, Santos-Pontelli TE, Cougo-Pinto PT, et al. . Validation of a structured interview for telephone assessment of the modified Rankin Scale in Brazilian stroke patients. Cerebrovasc Dis 2014;38:297–301. 10.1159/000367646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wegener S, Artmann J, Luft AR, et al. . The time of maximum post-ischemic hyperperfusion indicates infarct growth following transient experimental ischemia. PLoS One 2013;8:e65322 10.1371/journal.pone.0065322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schaefer PW, Grant PE, Gonzalez RG. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of the brain. Radiology 2000;217:331–45. 10.1148/radiology.217.2.r00nv24331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, et al. . Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:822–38. 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70124-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lavdas E, Tsougos I, Kogia S, et al. . T2 FLAIR artifacts at 3-T brain magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Imaging 2014;38:85–90. 10.1016/j.clinimag.2013.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Federau C, Mlynash M, Christensen S, et al. . Evolution of volume and signal intensity on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MR images after endovascular stroke therapy. Radiology 2016;280:184–92. 10.1148/radiol.2015151586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-018160supp001.pdf (515.2KB, pdf)