Abstract

In recent years numerous studies have indicated the importance of microRNAs (miRNA/miRs) in human pathology. Down syndrome (DS) is the most prevalent survivable chromosomal disorder and is attributed to trisomy 21 and the subsequent alteration of the dosage of genes located on this chromosome. A number of miRNAs are overexpressed in down syndrome, including miR-155, miR-802, miR- 125b-2, let-7c and miR-99a. This overexpression may contribute to the neuropathology, congenital heart defects, leukemia and low rate of solid tumor development observed in patients with DS. MiRNAs located on other chromosomes and with associated target genes on or off chromosome 21 may also be involved in the DS phenotype. In the present review, an overview of miRNAs and the haploinsufficiency and protein translation of specific miRNA targets in DS are discussed. This aimed to aid understanding of the pathogenesis of DS, and may contribute to the development of novel strategies for the prevention and treatment of the pathologies of DS.

Keywords: Down syndrome, microRNAs, trisomy 21

1. Introduction

Down syndrome (DS) is the most prevalent chromosomal disorder with an incidence rate between 1 in 1,000 to 1 in 1,100 live births worldwide (1). The incidence rate is higher in mothers of >35-years-old and increases with further advances in maternal age (2). DS was clinically described by John Langdon Down in 1866, prior to the identification of the genetic basis of the syndrome (3). Subsequently, an additional chromosome of the later termed chromosome 21, as the cause of DS, was discovered in 1959 by Lejeune et al (4). It is reported that ~95% of patients with DS have this type of trisomy, and that ~4% of children with DS exhibit trisomy 21 due to translocation between chromosome 21 and most often an acrocentric chromosome (5). Additionally, ~1% of patients are mosaic, and exhibit somatic cells with normal karyotype alongside others with trisomy (5). These patients typically present with a less serious phenotype. Rarely, there is partial trisomy 21, characterized by triplication of only part of chromosome 21 (6). This can aid to determine the regions of chromosome 21 that are key contributors to the DS phenotype. Regarding DS phenotype, it has been reported that the D21S55 region on proximal 21q22.3 contains genes that, when overexpressed, serve major roles in the pathogenesis of DS (7). However, genes outside this region also contribute to DS phenotypes (8). Furthermore, the etiology of the DS phenotype is complex and includes other mechanisms, including epigenetic pathways (9). To date, there has been no pathogenetic model linking specific structural and functional aspects of chromosome 21 to the DS phenotype. Nonetheless, in recent years, the involvement of non-coding RNAs, including microRNAs (miRNA/miRs), and epigenetic mechanisms have been linked to the DS phenotype, particularly to the intellectual disability associated with DS.

miRNAs are endogenous RNAs of ~23 nucleotides in length that pair with the mRNAs of protein-coding genes to direct post-transcriptional repression, and thus serve important roles in regulating genes in eukaryotes (10). Notably, a range of cellular processes, including cell proliferation, apoptosis and tumorigenesis, organogenesis, hematopoiesis and developmental timing, are controlled by miRNAs (11).

In the present review, the possible involvement of multiple miRNAs in the development of the DS phenotype, characterized by mental retardation, congenital heart defects, leukemia, the absence of cardiovascular disease and a low rate of solid tumor development, is summarized.

2. Down syndrome

DS is a gene dosage disorder caused by increased production of the gene products of chromosome 21. For instance, in DS, the triplicate copy of superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) gene, located on 21q22.11, is responsible for overproduction of SOD1, which leads to the oxidative stress observed in DS patients (12). This oxidative stress may manifest as multiple characteristics of the DS phenotype, including as cataractogenesis (12) and premature aging (13). Variable mental retardation occurs in all patients, and the malformative features of the phenotype are also variable (3). Generally patients with DS are underweight and exhibit delayed growth, severe hypotonia and several dysmorphic features (8). The latter includes brachycephaly and plagiocephaly, upslanting palpebral fissures, epicanthus, low-set ears, tongue protrusion, short hands, single transverse palmar crease and clinodactyly (14). Individuals with DS develop a high frequency of infections due to immunological and non-immunological factors. Among the immunological factors are suboptimal antibody responses and poor cellular chemotaxis (15), while the non-immune factors include airway anomalies, gastro-oesophageal reflux and ear anomalies (15). Additionally, ~40% of patients exhibit congenital heart defects (16).

DS patients also have transient leukemoid reactions (17) and an increased risk of developing leukemia, most commonly megakaryoblastic (M7) leukemia (18). This may be due to somatic mutations of the X-chromosomal gene encoding GATA-binding protein 1 (GATA1), an important transcriptional regulator of normal megakaryocytic differentiation, which have generally been identified in DS leukemic cells (19).

Notably, the frequency of solid tumors in DS, namely neuroblastomas and nephroblastomas in infants and common epithelial tumors in adults, is reduced compared with normal populations (20). The involvement of two genes has been implicated in this lower tumor incidence in individuals with trisomy 21, namely ETS proto-oncogene 2 (ETS2) (21) and DS candidate region-1 (DSCR1), with the latter encoding a protein that is able to suppress tumor growth in mice (22). DSCR1 also regulates the calcineurin pathway to suppress vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated angiogenic signalling (22).

Patients with DS develop premature dementia and have an increased risk of Alzheimer's disease (23), probably due to the roles of amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene, located on 21q21.3, in DS and AD. Indeed, partial trisomy 21 without triplication of the APP gene does not lead to AD (24). Furthermore, compared with healthy individuals, significantly lower systolic and diastolic blood pressures and absence of atherosclerosis are reported in DS patients (25,26). This protection against atherosclerosis may be due to the reduced level of heart-type fatty acid binding protein (27). A number of DS patients also present gastrointestinal disorders, namely duodenal stenosis, gastroesophageal reflux, imperforate anus and Hirschsprung's disease (28). Hypothyroidism also frequently develops in DS patients (29). Collectively these reports demonstrate the complexity and distinct characteristics of the DS phenotype.

3. miRNAs

Primary miRNA transcripts (pri-miRNAs) that contain cap structures and poly(A) tails are generated by RNA polymerase II, which transcribes miRNA genes (30). The maturation of pri-miRNAs occurs by two main events: i) Processing of the pri-miRNAs into stem-loop precursors of ~70 nucleotides (pre-miRNAs) in the nucleus, and ii) processing of pre-miRNAs into mature miRNAs in the cytoplasm (31). The initiation step of miRNA processing in the nucleus is cleavage by the RNase III, human Drosha (32). This nuclease is a component of two multi-protein complexes: A larger complex containing multiple classes of RNA-associated proteins and a smaller complex composed of Drosha and the double-stranded-RNA-binding protein DGCR8, the product of the DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene 8 (33). Exportin-5 mediates the nuclear export of pre-miRNAs and binds processed pre-miRNAs in a Ran guanosine triphosphate-dependent manner (34). In the cytoplasm, the pre-RNA is processed by Dicer, generating an miRNA of ~22 nucleotides long (35). These miRNA sequences are incorporated into the RNA-induced silence complex (RISC) that targets mRNAs for degradation (35). However, only a single strand of the miRNA duplex remains in the RISC complex to control the expression of target genes (36).

miRNAs bind to the 3´-untranslated region (3´-UTR) of target mRNAs to suppress their expression. Interactions among factors associated with the 3´UTR of the target mRNA, including translation regulators, RISC and mRNA decay factors, may determine the trigger event of miRNA-mediated gene silencing (37). Due to the limited complementarity between miRNAs and their targets, there are hundreds of potential mRNA targets per miRNA (38). Thus, a single miRNA may regulate multiple biological processes (39), and several miRNAs can regulate an individual target (38). Additionally, miRNA expression varies depending on cell type and cellular conditions (38). The implications of miRNAs in the pathogenesis of DS are subsequently addressed.

4. Down syndrome and chromosome 21 miRNAs

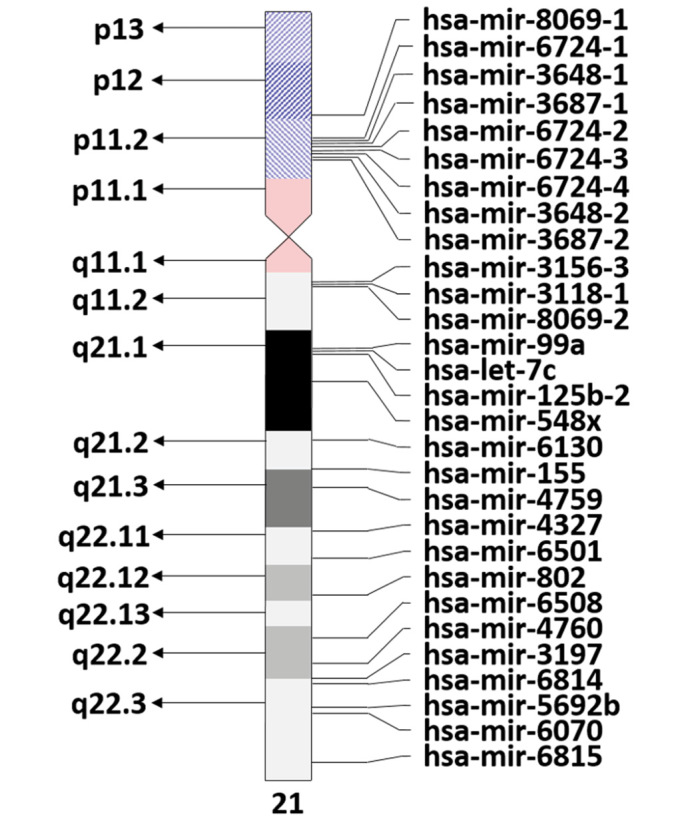

The miRBase (http://www.mirbase.org/search.shtml, accessed on 4/9/2017) indicates the presence of 29 Homo sapiens miRNAs on chromosome 21 (Fig. 1). However, only some of these miRNAs have been identified to have transcription levels at the expected 1.5 ratio due to chromosome 21 trisomy in DS (40). Notably, five of these miRNAs that meet the overexpression ratio, namely miR-155, miR-802, miR- 125b-2, let-7c and miR-99a, have been implicated to be involved in DS (41,42). In turn, the specific target genes of these miRNAs are haploinsufficient in DS (43,44). For instance, miR-155 targets complement factor H mRNA (CFH), which is decreased in DS tissues (45). As CFH protects neurons from axonal injury, complement opsonization, and leukocyte infiltration in the brain parenchyma (46), overexpression of miR-155 may be involved in the brain pathology of DS patients. Additionally, CFH is a repressor of the immune response (45). Thus, among other known factors described above (15), this repression may be a cause of susceptibility to infection in DS patients.

Figure 1.

miRNA loci on chromosome 21. mir/miRNA, microRNA; hsa, Homo sapiens.

In T21 induced pluripotent stem neuronal progenitor cells (iPS-NPCs), Lu et al (47) observed the degradation of methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2) following overexpression of miR-155 and miR-802. Additionally, they observed that T21 iPS-NPCs exhibited developmental defects and generated fewer neurons than controls (47). Decreased MeCP2 may also contribute to the neurochemical abnormalities observed in the brains of DS individuals (43). In the study of hippocampal neurons from mice that either lacked expression or expressed twice the normal levels of MeCP2, Chao et al (48) identified that the regulation of glutamatergic synapse number by MeCP2 may be a mechanism for the altered synaptic strength of neurons in DS. Keck-Wherley et al (49) reported that miR-155 and miR-802 were significantly increased in the DS mouse model Ts65Dn, and that significant overexpression of these miRNAs may be implicated in hippocampal deficits in DS phenotypes. Indeed, the hippocampus is an important region involved in learning and memory and in long-term synaptic plasticity.

Underexpression of angiotensin II type 1 receptor, a target of miR-155, may explain the absence of cardiovascular disease in DS individuals (43), as this receptor has been implicated in cardiovascular pathologies (50). Additionally, Coppola et al (51) observed overexpression of the miR-99a/let-7c cluster and subsequent decrease of their targets in fetal DS heart tissue, suggesting that the cluster may contribute to congenital heart defects in DS.

miR-125b-2 may serve a role in the regulation of megakaryopoiesis and may be an oncogenic miRNA involved in the pathogenesis of megakaryoblastic leukemia observed in DS (52). Zhang et al (53) demonstrated that the most expressed miRNAs in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia (AML) were miR-100, miR-125b, miR-335, miR-146, and miR-99a. MiR-155 was also identified to be elevated in the bone marrow of some patients with AML (54). Furthermore, leukemic cells from DS patients with acute megakaryoblastic leukemia have been demonstrated to contain acquired mutations in GATA1, which serves as an important hematopoietic transcription factor (55). Shaham et al (56) also documented a cooperation between GATA1 and miR-486-5p and observed that miR-486-5p enhanced the survival of leukemic cells from DS patients.

Overexpression of miR-125a or miR-125b in an Erb-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2-dependent human breast cancer cell line impaired its growth potential and reduced its motility and invasive capabilities (57). Overexpression of the miRNA let-7 has also been identified in breast cancer, and may regulate the tumorigenicity of breast cancer cells (58). In particular, let-7c inhibited the tumor formation capacity of breast cancer stem cells (59). These results may explain the low rate of breast cancer among women with DS.

Furthermore, Johnson et al (60) demonstrated that let-7 was highly expressed in lung tissue, repressed cell proliferation in lung cells and affected cell cycle progression in a liver cancer cell line. They also identified that let-7 regulated cell cycle-related genes involved in the repression of cell proliferation pathways (60). In particular, let-7c may inhibit lung adenocarcinoma proliferation (61).

Prostate cancer is also less common in patients with DS compared with healthy individuals (62). The miR-99 family of miRNAs have been reported to inhibit the proliferation of prostate cancer cells and decrease the expression of prostate-specific antigen, a biomarker for prostate cancer diagnosis (63).

Collectively these reports may explain the low risk of solid tumor development in patients with DS (64). However, other factors have been suggested to explain this low tumor risk, including high expression of the calcineurin inhibitor DSCR1 on the basis of its inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated angiogenic signalling (22).

A previous study identified two novel miRNAs, miR-nov1 and miR-nov2, on chromosome 21, located up- and downstream of the annotated miR-802 loci (40). miR-nov2 is located in the ‘DS critical region’ (chr21q22.2) and its overexpression has been identified in DS lymphocytes (40). Xu et al (40) predicted that the 97 mRNA targets of miR-nov2 were associated with cell growth, cell death, cellular localization and protein transport. In a subsequent study, they also confirmed the identification of miR-nov1 and miRnov2 in cord blood mononuclear cells of DS fetuses (65). Notably, it was observed that miR-99a, let-7c, miR-125b-2 and miR-155 were downregulated in DS cells (65). Thus, the role of these miRNAs in the development of the DS phenotype should be investigated.

5. miRNAs derived from other chromosomes associated with DS phenotype

Using microarray technology to identify miRNAs that were aberrantly expressed, Lim et al (66) compared genome-wide miRNA expression in the placentas of normal and DS fetuses. They observed that no chromosome 21-derived miRNAs were differentially expressed. However, of the 584 genes on chromosome 21, 76 were differentially expressed and possible targets of miRNAs. These target genes on chromosome 21 were significantly associated with DS phenotypes, including mental retardation and congenital abnormalities (66). Nevertheless, the absence of differentially expressed miRNAs on chromosome 21 between DS and normal placentas disagrees with other studies conducted in fetal cord blood cells (65). Lim et al (66) proposed that this variance may be due to differences in the characteristics of tissues reported in previous studies. Indeed, Liang et al (67) identified that numerous miRNAs had distinct expression in the placenta compared with other tissues.

However, the results of Lim et al are also contrasting to the results of Svobodová et al (68), who observed that three miRNAs located on chromosome 21 (miR-99a, miR-125b and let-7c) and four miRNAs located on other chromosomes (miR-542-5p, miR-10b, miR-615 and miR-654) were upregulated in DS placentas. Additionally, Lim et al (69) reported that miRNA expression was significantly different between blood and placenta samples, and that mir-1973 and mir-3196 were overexpressed in the trisomy 21 placenta. These two miRNAs may regulate target genes involved in development of the nervous system (69).

Shi et al (70) studied the microRNA expression profile of hippocampal tissues from DS fetuses using miRNA microarray, and reported that the function of miR-138-5p and the downregulation of its target, enhancer of zeste homolog 2, in the hippocampus may be involved in the intellectual disability of DS patients. Furthermore, Wang et al (71) reported that interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-12 receptor subunit β2, autism susceptibility candidate 2 (AUTS2) and KIAA2022 may be involved in atrioventricular septal defect in DS patients, and that AUTS2 and KIAA2022 may be targeted by miR-518a, miR-518e, miR-518f, miR-528a and miR-96.

Lin et al (72) studied the expression profiles of miRNA and protein in cord blood samples from DS and normal fetuses, and reported that three miRNAs (miR-329, miR-27b and miR-27a) and seven proteins (growth factor receptor-bound protein 2, thymosin β10, RuvB-like 2, mitogen-activated protein kinase 1, tyrosine-protein phosphatase non-receptor type 11, α-actin-2 and protein tyrosine kinase 2) exhibited high levels of differential expression in DS fetuses. This differential expression may serve a role in the pathogenesis of DS. More recently, Arena et al (73) reported a higher level of miR-146a expression in astroglial cells within the hippocampal white matter of DS fetuses compared with normal fetuses, and identified persistence of this elevated expression postnatally. This may be a key finding, as the expression level of miR-146a has been suggested as an important determinant for neuronal development (74).

Thus, the study of these miRNAs in DS cells may contribute towards greater comprehension of the DS phenotype.

6. Conclusion

The overexpression of several miRNAs, including miR-155, miR-802, miR-99 and let-7c, and the consequent haploinsufficiency of their specific target proteins are potentially involved in the DS phenotype. In particular, miR-155 and miR-802 may be involved in neuropathology, the cluster miR-99/let-7c in congenital heart defects and miR-155 in the absence of cardiovascular disease observed in DS. Additionally, miR-125b-2, miR-155 and miR-99a possibly serve roles in the pathogenesis of megakaryoblastic leukemia in DS patients. A number of miRNAs expressed in DS patients may also be implicated in the low rate of solid tumor development in DS patients, including miR-125b and let-7c in breast cancer, miR-99 in prostate cancer and let-7c in lung cancer. Nevertheless, the role of miRNAs located on other chromosomes, and with target genes are on or off chromosome 21, should not be excluded from the DS phenotype.

Acknowledgements

The present review was financed by National Funds through the FCT Foundation for Science and Technology (project no. UID/BIM/00009/2016).

References

- 1.World Health Organization, corp-author. Genomic Resource Centre: Genes and human disease. http://www.who.int/genomics/public/geneticdiseases/en/index1.html. [Sep 4;2017 ]. http://www.who.int/genomics/public/geneticdiseases/en/index1.html

- 2.Hultén MA, Patel S, Jonasson J, Iwarsson E. On the origin of the maternal age effect in trisomy 21 Down syndrome: The Oocyte Mosaicism Selection model. Reproduction. 2010;139:1–9. doi: 10.1530/REP-09-0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Speicher MR. Chromosomes. In: Speicher MR, Antonarakis SE, Motulsky AG, editors. Vogel and Motulsky's Human Genetics Problems and Approaches. Springer-Verlag; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2010. pp. 55–138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lejeune J, Gauthier M, Turpin R. Human chromosomes in tissue cultures. C R Hebd Seances Acad Sci. 1959;248:602–603. (In French) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mutton D, Alberman E, Hook EB. National Down Syndrome Cytogenetic Register and the Association of Clinical Cytogeneticists: Cytogenetic and epidemiological findings in Down syndrome, England and Wales 1989 to 1993. J Med Genet. 1996;33:387–394. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.5.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raoul O, Carpentier S, Dutrillaux B, Mallet R, Lejeune J. Partial trisomy of chromosome 21 by maternal translocation t(15;21) (q26.2; q21) Ann Genet. 1976;19:187–190. (In French) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahmani Z, Blouin JL, Créau-Goldberg N, Watkins PC, Mattei JF, Poissonnier M, Prieur M, Chettouh Z, Nicole A, Aurias A, et al. Down syndrome critical region around D21S55 on proximal 21q22.3. Am J Med Genet Suppl. 1990;7:98–103. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320370720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korenberg JR, Chen XN, Schipper R, Sun Z, Gonsky R, Gerwehr S, Carpenter N, Daumer C, Dignan P, Disteche C. Down syndrome phenotypes: The consequences of chromosomal imbalance; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 1994; pp. 4997–5001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Do C, Xing Z, Yu YE, Tycko B. Trans-acting epigenetic effects of chromosomal aneuploidies: Lessons from Down syndrome and mouse models. Epigenomics. 2017;9:189–207. doi: 10.2217/epi-2016-0138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: Target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim VN. MicroRNA biogenesis: Coordinated cropping and dicing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:376–385. doi: 10.1038/nrm1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brás A, Monteiro C, Rueff J. Oxidative stress in trisomy 21. A possible role in cataractogenesis. Ophthalmic Paediatr Genet. 1989;10:271–277. doi: 10.3109/13816818909009882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campos C, Guzmán R, López-Fernández E, Casado A. Urinary uric acid and antioxidant capacity in children and adults with Down syndrome. Clin Biochem. 2010;43:228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nussbaum RL, McInnes RR, Willard HF, editors. Thompson & Thompson Genetics in Medicine. Saunders Elsevier; 2007. Clinical Cytogenetics: Disorders of the autosomes and the sex chromosomes; pp. 89–113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ram G, Chinen J. Infections and immunodeficiency in Down syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;164:9–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04335.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freeman SB, Bean LH, Allen EG, Tinker SW, Locke AE, Druschel C, Hobbs CA, Romitti PA, Royle MH, Torfs CP, et al. Ethnicity, sex, and the incidence of congenital heart defects: A report from the National Down Syndrome Project. Genet Med. 2008;10:173–180. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181634867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fong CT, Brodeur GM. Down's syndrome and leukemia: Epidemiology, genetics, cytogenetics and mechanisms of leukemogenesis. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1987;28:55–76. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(87)90354-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Creutzig U, Ritter J, Vormoor J, Ludwig WD, Niemeyer C, Reinisch I, Stollmann-Gibbels B, Zimmermann M, Harbott J. Myelodysplasia and acute myelogenous leukemia in Down's syndrome. A report of 40 children of the AML-BFM study group. Leukemia. 1996;10:1677–1686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hitzler JK, Zipursky A. Origins of leukaemia in children with Down syndrome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:11–20. doi: 10.1038/nrc1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Satgé D, Sommelet D, Geneix A, Nishi M, Malet P, Vekemans M. A tumor profile in Down syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1998;78:207–216. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19980707)78:3<207::AID-AJMG1>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sussan TE, Yang A, Li F, Ostrowski MC, Reeves RH. Trisomy represses Apc(Min)-mediated tumours in mouse models of Down's syndrome. Nature. 2008;451:73–75. doi: 10.1038/nature06446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baek KH, Zaslavsky A, Lynch RC, Britt C, Okada Y, Siarey RJ, Lensch MW, Park IH, Yoon SS, Minami T, et al. Down's syndrome suppression of tumour growth and the role of the calcineurin inhibitor DSCR1. Nature. 2009;459:1126–1130. doi: 10.1038/nature08062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartley D, Blumenthal T, Carrillo M, DiPaolo G, Esralew L, Gardiner K, Granholm AC, Iqbal K, Krams M, Lemere C, et al. Down syndrome and Alzheimer's disease: Common pathways, common goals. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:700–709. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prasher VP, Farrer MJ, Kessling AM, Fisher EM, West RJ, Barber PC, Butler AC. Molecular mapping of Alzheimer-type dementia in Down's syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:380–383. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murdoch JC, Rodger JC, Rao SS, Fletcher CD, Dunnigan MG. Down's syndrome: An atheroma-free model? BMJ. 1977;2:226–228. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6081.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ylä-Herttuala S, Luoma J, Nikkari T, Kivimäki T. Down's syndrome and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 1989;76:269–272. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(89)90110-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vianello E, Dogliotti G, Dozio E, Corsi Romanelli MM. Low heart-type fatty acid binding protein level during aging may protect down syndrome people against atherosclerosis. Immun Ageing. 2013;10:2. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-10-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buchin PJ, Levy JS, Schullinger JN. Down's syndrome and the gastrointestinal tract. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8:111–114. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198604000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Purdy IB, Singh N, Brown WL, Vangala S, Devaskar UP. Revisiting early hypothyroidism screening in infants with Down syndrome. J Perinatol. 2014;34:936–940. doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee Y, Kim M, Han J, Yeom KH, Lee S, Baek SH, Kim VN. MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 2004;23:4051–4060. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee Y, Jeon K, Lee JT, Kim S, Kim VN. MicroRNA maturation: Stepwise processing and subcellular localization. EMBO J. 2002;21:4663–4670. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee Y, Ahn C, Han J, Choi H, Kim J, Yim J, Lee J, Provost P, Rådmark O, Kim S, et al. The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature. 2003;425:415–419. doi: 10.1038/nature01957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gregory RI, Yan KP, Amuthan G, Chendrimada T, Doratotaj B, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R. The Microprocessor complex mediates the genesis of microRNAs. Nature. 2004;432:235–240. doi: 10.1038/nature03120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lund E, Güttinger S, Calado A, Dahlberg JE, Kutay U. Nuclear export of microRNA precursors. Science. 2004;303:95–98. doi: 10.1126/science.1090599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bernstein E, Caudy AA, Hammond SM, Hannon GJ. Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature. 2001;409:363–366. doi: 10.1038/35053110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwarz DS, Hutvágner G, Du T, Xu Z, Aronin N, Zamore PD. Asymmetry in the assembly of the RNAi enzyme complex. Cell. 2003;115:199–208. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00759-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu W, Coller J. What comes first: Translational repression or mRNA degradation? The deepening mystery of microRNA function. Cell Res. 2012;22:1322–1324. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saito T, Saetrom P. MicroRNAs-targeting and target prediction. N Biotechnol. 2010;27:243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Min A, Zhu C, Peng S, Rajthala S, Costea DE, Sapkota D. MicroRNAs as important players and biomarkers in oral carcinogenesis. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:186904. doi: 10.1155/2015/186904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu Y, Li W, Liu X, Chen H, Tan K, Chen Y, Tu Z, Dai Y. Identification of dysregulated microRNAs in lymphocytes from children with Down syndrome. Gene. 2013a;530:278–286. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siew WH, Tan KL, Babaei MA, Cheah PS, Ling KH. MicroRNAs and intellectual disability (ID) in Down syndrome, X-linked ID, and Fragile X syndrome. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:41. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alexandrov PN, Percy ME, Lukiw WJ. Chromosome 21-Encoded microRNAs (mRNAs): Impact on Down's syndrome and trisomy-21 linked disease. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2017 Jul 7; doi: 10.1007/s10571-017-0514-0. (Epub ahead of print). doi.org/10.1007/s10571-017-0514-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elton TS, Sansom SE, Martin MM. Trisomy-21 gene dosage over-expression of miRNAs results in the haploinsufficiency of specific target proteins. RNA Biol. 2010;7:540–547. doi: 10.4161/rna.7.5.12685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elton TS, Selemon H, Elton SM, Parinandi NL. Regulation of the MIR155 host gene in physiological and pathological processes. Gene. 2013;532:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li YY, Alexandrov PN, Pogue AI, Zhao Y, Bhattacharjee S, Lukiw WJ. miRNA-155 upregulation and complement factor H deficits in Down's syndrome. Neuroreport. 2012;23:168–173. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32834f4eb4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Griffiths MR, Neal JW, Fontaine M, Das T, Gasque P. Complement factor H, a marker of self protects against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2009;182:4368–4377. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0800205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lu HE, Yang YC, Chen SM, Su HL, Huang PC, Tsai MS, Wang TH, Tseng CP, Hwang SM. Modeling neurogenesis impairment in Down syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cells from Trisomy 21 amniotic fluid cells. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319:498–505. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chao HT, Zoghbi HY, Rosenmund C. MeCP2 controls excitatory synaptic strength by regulating glutamatergic synapse number. Neuron. 2007;56:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keck-Wherley J, Grover D, Bhattacharyya S, Xu X, Holman D, Lombardini ED, Verma R, Biswas R, Galdzicki Z. Abnormal microRNA expression in Ts65Dn hippocampus and whole blood: Contributions to Down syndrome phenotypes. Dev Neurosci. 2011;33:451–467. doi: 10.1159/000330884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Billet S, Aguilar F, Baudry C, Clauser E. Role of angiotensin II AT1 receptor activation in cardiovascular diseases. Kidney Int. 2008;74:1379–1384. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coppola A, Romito A, Borel C, Gehrig C, Gagnebin M, Falconnet E, Izzo A, Altucci L, Banfi S, Antonarakis SE, et al. Cardiomyogenesis is controlled by the miR-99a/let-7c cluster and epigenetic modifications. Stem Cell Res (Amst) 2014;12:323–337. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Klusmann JH, Li Z, Böhmer K, Maroz A, Koch ML, Emmrich S, Godinho FJ, Orkin SH, Reinhardt D. miR-125b-2 is a potential oncomiR on human chromosome 21 in megakaryoblastic leukemia. Genes Dev. 2010;24:478–490. doi: 10.1101/gad.1856210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang H, Luo XQ, Zhang P, Huang LB, Zheng YS, Wu J, Zhou H, Qu LH, Xu L, Chen YQ. MicroRNA patterns associated with clinical prognostic parameters and CNS relapse prediction in pediatric acute leukemia. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7826. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O'Connell RM, Rao DS, Chaudhuri AA, Boldin MP, Taganov KD, Nicoll J, Paquette RL, Baltimore D. Sustained expression of microRNA-155 in hematopoietic stem cells causes a myeloproliferative disorder. J Exp Med. 2008;205:585–594. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wechsler J, Greene M, McDevitt MA, Anastasi J, Karp JE, Le Beau MM, Crispino JD. Acquired mutations in GATA1 in the megakaryoblastic leukemia of Down syndrome. Nat Genet. 2002;32:148–152. doi: 10.1038/ng955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shaham L, Vendramini E, Ge Y, Goren Y, Birger Y, Tijssen MR, McNulty M, Geron I, Schwartzman O, Goldberg L, et al. MicroRNA-486-5p is an erythroid oncomiR of the myeloid leukemias of Down syndrome. Blood. 2015;125:1292–1301. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-581892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scott GK, Goga A, Bhaumik D, Berger CE, Sullivan CS, Benz CC. Coordinate suppression of ERBB2 and ERBB3 by enforced expression of micro-RNA miR-125a or miR-125b. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:1479–1486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609383200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu F, Yao H, Zhu P, Zhang X, Pan Q, Gong C, Huang Y, Hu X, Su F, Lieberman J, et al. let-7 regulates self renewal and tumorigenicity of breast cancer cells. Cell. 2007;131:1109–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sun X, Xu C, Tang SC, Wang J, Wang H, Wang P, Du N, Qin S, Li G, Xu S, et al. Let-7c blocks estrogen-activated Wnt signaling in induction of self-renewal of breast cancer stem cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 2016;23:83–89. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2016.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johnson CD, Esquela-Kerscher A, Stefani G, Byrom M, Kelnar K, Ovcharenko D, Wilson M, Wang X, Shelton J, Shingara J, et al. The let-7 microRNA represses cell proliferation pathways in human cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7713–7722. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang PY, Sun YX, Zhang S, Pang M, Zhang HH, Gao SY, Zhang C, Lv CJ, Xie SY. Let-7c inhibits A549 cell proliferation through oncogenic TRIB2 related factors. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:2675–2681. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Patja K, Pukkala E, Sund R, Iivanainen M, Kaski M. Cancer incidence of persons with Down syndrome in Finland: A population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1769–1772. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sun D, Lee YS, Malhotra A, Kim HK, Matecic M, Evans C, Jensen RV, Moskaluk CA, Dutta A. miR-99 family of MicroRNAs suppresses the expression of prostate-specific antigen and prostate cancer cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1313–1324. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hasle H. Pattern of malignant disorders in individuals with Down's syndrome. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:429–436. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(00)00435-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xu Y, Li W, Liu X, Ma H, Tu Z, Dai Y. Analysis of microRNA expression profile by small RNA sequencing in Down syndrome fetuses. Int J Mol Med. 2013b;32:1115–1125. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lim JH, Kim DJ, Lee DE, Han JY, Chung JH, Ahn HK, Lee SW, Lim DH, Lee YS, Park SY, et al. Genome-wide microRNA expression profiling in placentas of fetuses with Down syndrome. Placenta. 2015a;36:322–328. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2014.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liang Y, Ridzon D, Wong L, Chen C. Characterization of microRNA expression profiles in normal human tissues. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:166. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Svobodová I, Korabečná M, Calda P, Břešťák M, Pazourková E, Pospíšilová Š, Krkavcová M, Novotná M, Hořínek A. Differentially expressed miRNAs in trisomy 21 placentas. Prenat Diagn. 2016;36:775–784. doi: 10.1002/pd.4861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lim JH, Lee DE, Kim SY, Kim HJ, Kim KS, Han YJ, Kim MH, Choi JS, Kim MY, Ryu HM, et al. MicroRNAs as potential biomarkers for noninvasive detection of fetal trisomy 21. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2015b;32:827–837. doi: 10.1007/s10815-015-0429-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shi WL, Liu ZZ, Wang HD, Wu D, Zhang H, Xiao H, Chu Y, Hou QF, Liao SX. Integrated miRNA and mRNA expression profiling in fetal hippocampus with Down syndrome. J Biomed Sci. 2016;23:48. doi: 10.1186/s12929-016-0265-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang L, Li Z, Song X, Liu L, Su G, Cui Y. Bioinformatic analysis of genes and microRNAs associated with atrioventricular septal defect in Down syndrome patients. Int Heart J. 2016;57:490–495. doi: 10.1536/ihj.15-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lin H, Sui W, Li W, Tan Q, Chen J, Lin X, Guo H, Ou M, Xue W, Zhang R, et al. Integrated microRNA and protein expression analysis reveals novel microRNA regulation of targets in fetal down syndrome. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14:4109–4118. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Arena A, Iyer AM, Milenkovic I, Kovács GG, Ferrer I, Perluigi M, Aronica E. Developmental expression and dysregulation of miR-146a and miR-155 in Down's syndrome and mouse models of Down's syndrome and Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2017 Jul 6;14 doi: 10.2174/1567205014666170706112701. (Epub ahead of print). doi.org/10.2174/1567205014666170706112701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nguyen LS, Lepleux M, Makhlouf M, Martin C, Fregeac J, Siquier-Pernet K, Philippe A, Feron F, Gepner B, Rougeulle C, et al. Profiling olfactory stem cells from living patients identifies miRNAs relevant for autism pathophysiology. Mol Autism. 2016;7:1. doi: 10.1186/s13229-015-0064-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]