Abstract

Objectives

This study was designed to identify the services provided by community pharmacists in Kuwait and their views regarding self-care in pregnancy and lactation. In addition, it determined the pharmacists’ recommendations for treatment of pregnancy-related and breast feeding-related ailments.

Design

Cross-sectional questionnaire-based survey.

Setting

Community pharmacies in Kuwait.

Participants

207 pharmacies were randomly selected from the Ministry of Health database. One registered pharmacist was approached from each pharmacy. One hundred and ninety-two (92.8%) pharmacists agreed to participate and completed a self-administered questionnaire.

Outcomes

The proportions of pharmacists offering particular advice for health conditions in pregnancy and lactation, pharmacists’ recommendations for common and specific ailments during pregnancy and breast feeding, and pharmacists’ views about self-care in pregnancy and breast feeding.

Results

The top services provided to pregnant and lactating women were recommending vitamins and food supplements (89.8%) and contraception advice (83.4%), respectively. More than half of participants indicated that they would recommend medications for headache, constipation, cough, runny nose, sore throat, nausea/vomiting, indigestion, sore or cracked nipple and insufficient milk. Diarrhoea, haemorrhoids, insomnia, varicose vein, swelling of the feet and legs, vaginal itching, back pain, fever, mastitis and engorgement were frequently referred to the physician. Recommendations on medication use were occasionally inappropriate in terms of unneeded drug therapy, off-label use and safety. In relation to offering advice and solving medication and health problems of pregnant and lactating women, more than half of pharmacists indicated that they have sufficient knowledge (61.5%; 50.5%) and confidence (58.3%; 53.1%), respectively. Most of the respondents (88.5%) agreed that a continuing education programme on this topic would be of value for their practice.

Conclusion

The present findings show that respondents had different recommendations for treatment of pregnancy-related and lactation-related ailments; and also highlight the need for interventions, including continuing professional development and revision of the undergraduate pharmacy curriculum.

Keywords: community pharmacists, pregnancy, breast feeding, lactation, feto-maternal self-care, self-medication, Kuwait

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The strength of this survey included the high response rate, which could indicate the importance of this topic to community pharmacists and the length of time that they were willing to spend on completing the questionnaire.

Further strength was the adequate sample size and sampling method to produce a representative data regarding the study population; therefore, the present findings can be generalised at the community pharmacists level in Kuwait.

In addition, this study fills in a gap in the limited existing literature in the developing countries and provides useful pieces of information for community pharmacists’ services for pregnant and lactating women in the Middle Eastern region.

Limitations of this study include that the survey did not truly assess real-life situations; therefore, the extent of being definitely sure that respondents perform what they declare is not possible and open to recall bias or error.

Further limitation is the social desirability bias that the respondents might have offered favourable answers to conform to the more socially accepted view.

Introduction

Self-care is defined as ‘the action individuals take for themselves and their families to stay healthy and take care of minor and long term conditions, based on their knowledge and the information available, and working in collaboration with health and social care professionals where necessary’.1 Self-medication is a part of self-care behaviours, which is mainly considered in developed countries for minor illnesses by using over-the-counter (OTC) medications, while in developing countries it is considered for both minor and major illnesses as a wider spectrum of medications is available from community pharmacies without a prescription.2

The prevalence of self-medication throughout pregnancy was found to be in the range between 25% and 68%.3–7 The most commonly used OTC medications were analgesics, cough and common cold remedies, allergy products, laxatives, antacids, vitamins, antibiotics and herbal products.4 6 8 The rates of self-medication among breast feeding women ranged between 17% and 52%.9 10 The most used OTC medicines were analgesics, antispasmodics, laxatives and nasal decongestants.9 The effect of medication use during pregnancy and lactation is a major worry for both women and healthcare practitioners.11 Hence, there is a need for professional guidance for selection of appropriate and safe OTC medicines for each ailment.

In 2011, the International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP) Council approved a document on the valuable pharmacists’ roles to improve maternal, newborn and child health. These roles have been structured in accordance with the FIP/WHO Guidelines on Good Pharmacy Practice.12

Previous studies have evaluated the role of community pharmacists in providing advice or counselling regarding pregnancy-related and lactation-related ailments in the USA, France, the Netherlands, Canada, Iceland, Serbia, Norway, Thailand, Uganda and Qatar.13–18 The main findings of these studies included a variation in community pharmacists’ responses for treatment of common ailments during pregnancy and breast feeding, the recommendations of unsafe medications during pregnancy and lactation, and the different levels of pharmacists’ knowledge in the area of maternal–fetal medicine.

Additional studies regarding community pharmacists’ services for pregnant and lactating women still need to be performed, particularly in developing countries where most of medications can be obtained from the pharmacy without prescription. To our knowledge, only one study has explored the pharmacists’ knowledge and perceptions of maternal–fetal medicine in the Eastern Mediterranean region in Qatar.18 Hence, this study was designed to identify the services provided by community pharmacists regarding self-care in pregnancy and lactation, determine the pharmacists’ recommendations (services) for treatment of pregnancy-related and lactation-related ailments, and identify their views about self-care during pregnancy and lactation. Secondary objectives were to determine factors associated with pharmacists’: (1) recommendations for treatment of pregnancy-related and lactation-related ailments, (2) views about self-care of pregnant and breast feeding women and (3) need for continuing education.

Methods

The study design was a cross-sectional questionnaire-based survey. It was performed in Kuwait, a Middle-Eastern country with an area of 17 820 km2 and an approximate population of 3 065 850 individuals (2011 estimate).19 It was conducted during the period from March to December 2015. The study population comprised of employed community pharmacists in Kuwait.

PS power and sample size calculator V.3.05 was used to determine the sample size.20 One hundred and eight-six pharmacists would be needed to determine a 20% difference in proportion between two groups (eg, male vs female) with an 80% power and a 5% significance level. Presuming a response rate of 90%, a sample size of 207 community pharmacies were randomly selected from the six governorates using stratified and systematic random sampling.21 Due to the lack of lists with the names and addresses of community pharmacists in Kuwait, lists of community pharmacies at the various governorates were acquired from the Ministry of Health. The lists included a total of 348 pharmacies distributed across the six governorates of Kuwait. Only one full-licensed pharmacist was approached from pharmacies hiring more than one pharmacist. The aim of the survey was concisely explained to the pharmacist on duty (face to face). Pharmacists were free to refuse to take part in the study. Those who agreed to participate in the survey were handed the questionnaires and then were gathered from them anonymously after being completed within 1–2 weeks. They signed a consent form to participate in the study.

The study survey was adapted from validated questionnaires that were previously used in Thailand and France.14 16 A research group at Kuwait University established the content validity of the adapted survey. Its face validity was assessed with five community pharmacists for clarity of questions. Then the survey was pretested on 10 community pharmacists, and refinements were made as needed so that the survey was simple to comprehend and answer.

The pretested survey contained four sections (online supplementary appendix 1). Demographic and other characteristics of respondents were included in the first section. Section 2 contained 11 questions to provide information about the services provided by the community pharmacists regarding self-care in pregnancy and lactation. These questions were about the availability of information leaflet or brochure to promote health for pregnant and breast feeding women, experience in providing services for pregnant and breast feeding women, number of pregnant and breast feeding women who visited the pharmacy per week, the three services most commonly provided for pregnant and breast feeding women, the two symptoms and/or questions that both pregnant and breast feeding women most frequently consulted the pharmacists in the past and how do they know that women are pregnant or breast feeding. Seven of the above questions were close-ended. The third section included 16 common symptoms in pregnancy and 12 common symptoms in breast feeding for which pregnant and breast feeding women often seek advice from pharmacists. They were asked to indicate the recommendations (services) that they will provide for each symptom if being consulted by a pregnant or breast feeding women. They were needed to select from three options for each ailment as they would be in real-life situations: refer to a doctor, dispense medicine and provide only advice without dispensing medicine. If they decided to dispense medications, they were asked to indicate the names of the medications. The final section included 12 statements to identify the pharmacists’ views about self-care in pregnancy and breast feeding. The responses were measured using a five-point Likert scale (strongly disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree (neutral), agree and strongly agree). In addition to three questions to determine the pharmacists need for continuing education about self-care in pregnancy and breast feeding, the convenient method of delivering the continuing education for them, and the most common source of information used by them to prepare themselves for responding to symptoms during pregnancy and lactation were asked.

bmjopen-2017-018980supp001.pdf (308.9KB, pdf)

Data analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, V.23, IBM). Pharmacists’ responses were presented as percentages (95% CIs) and medians (IQRs). To simplify the results’ presentation in the text, those who answered ‘strongly agree’ or ‘agree’ were classified as ‘agreed’, and those who answered ‘strongly disagree’ or ‘disagree’ as having disagreed. The internal consistency for the sections to determine the pharmacists’ views about self-care in pregnancy and breast feeding was assessed using Cronbach’s α test.

The univariate logistic regression was used first to evaluate the association of respondents’ characteristics with the dependent variables. All variables with P<0.25 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis to determine the factors that are independently associated with each of the dependent variables. Only the results of multivariate logistic analysis are reported showing OR and 95% CI. Statistical significance was accepted at P<0.05.

Results

One hundred and ninety-two (92.8%) pharmacists agreed to participate in the study. Their median (IQR) age and experience as practitioners were 35 (11) years and 11 (7) years, respectively. Table 1 shows the respondents’ characteristics.

Table 1.

Characteristics of respondents (n=192)

| Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 127 | 66.1 |

| Female | 65 | 33.9 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 20–29 | 28 | 14.6 |

| 30–39 | 104 | 54.2 |

| ≥40 | 60 | 31.2 |

| Basic qualification in pharmacy | ||

| Bachelor of Pharmacy | 177 | 92.2 |

| Master of Pharmacy | 9 | 4.7 |

| Doctor of Pharmacy* | 6 | 3.1 |

| Postgraduate qualification(s) in pharmacy | ||

| Diploma | 15 | 7.8 |

| Master degree | 12 | 6.2 |

| PhD | 3 | 1.6 |

| Experience as practitioners (Years) | ||

| ≤10 | 92 | 47.9 |

| >10 | 100 | 52.1 |

| Location of pharmacy (governorates) | ||

| Hawalli | 57 | 29.7 |

| Al Farwaniyah | 43 | 22.4 |

| Al Ahmadi/Mubarak Alkabeer | 43 | 22.4 |

| Capital | 25 | 13.0 |

| Al Jahra | 24 | 12.5 |

*Doctor of pharmacy degree.

PhD, Doctor of Philosophy.

Above two-fifths (n=85; 44.3%; 95% CI 37.2% to 51.6%) of participants have information leaflets or brochures to promote health for pregnancy and lactation, and most of these were from pharmaceutical companies (66%). Most of the respondents had experience in providing services for pregnant (n=186; 96.9%; 95% CI 93.0% to 98.7%) and breast feeding (n=181; 94.3%; 95% CI 89.7% to 97.0%) women. The median (IQR) numbers of pregnant women and breast feeding women who visited the community pharmacy per week were 10 (7) and 6 (3), respectively.

Community pharmacists who reported to have experience in providing services for pregnant and breast feeding women were asked to indicate the most frequently provided services. The top three services provided for pregnant women were recommending vitamins and food supplements (n=167; 89.8%; 95% CI 84.3% to 93.6%), referral to a doctor (n=126; 67.7%; 95% CI 60.5% to 74.3%) and providing advice about suitable behaviour such as lifestyle and exercise (n=115; 61.8%; 95% CI 54.4% to 68.8%). Other offered services, but to a lesser extent, were diagnosis of symptoms and dispensing of medicines (n=100; 53.8%; 95% CI 46.3% to 61.0%) and herbal products (n=80; 43.0%; 95% CI 35.9% to 50.5%). The three services most frequently provided for breast feeding women were contraception advice (n=151; 83.4%; 95% CI 77.0% to 88.4%), recommending vitamins and food supplements (n=101; 55.8%; 95% CI 48.3% to 63.1%) and weight control advice (n=92; 50.8%; 95% CI 43.3% to 58.3%). The other offered services, but to a lesser extent, were diagnosis of symptoms and dispensing of herbal products (n=88; 48.6%; 95% CI 41.2% to 56.1%) and medicines (n=69; 38.1%; 95% CI 31.1% to 45.7%), and referral to a doctor (n=58; 32.0%; 95% CI 25.4% to 39.4%). About three-fifths (n=106; 58.6%; 95% CI 51.0% to 65.8%) of respondents stated that they knew women are pregnant or breast feeding by asking them, while 41.4% (n=75; 95% CI 34.3% to 49.0%) reported that women inform them before asking about the services.

Moreover, respondents indicated that they were most often consulted by pregnant women regarding gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea/vomiting, constipation and stomach cramp), respiratory symptoms (common cold and cough), safety of medication use and back pain. Breast feeding women most frequently consulted them about a medicine to increase breast milk, contraceptive pills, safety of medication use and respiratory symptoms (common cold and cough).

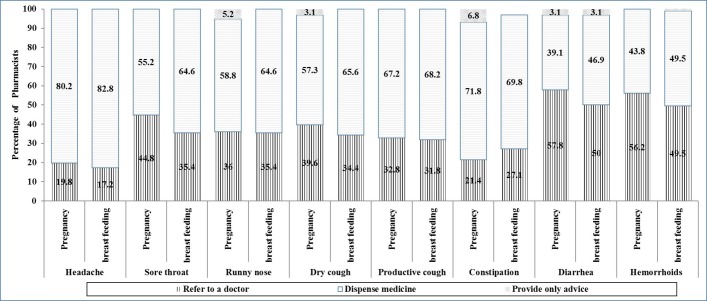

Figure 1 presents the distribution of pharmacists’ responses to the most commonly treated symptoms during pregnancy and breast feeding. Most of the pharmacists recommended medicines or referral to a doctor rather than providing advice only without dispensing medicine for treatment of these symptoms. More than half of participants recommended medications for treatment of headache, constipation, cough, sore throat and runny nose. In relation to diarrhoea and haemorrhoids, about three-fifths and half of respondents recommended referral to a doctor rather than dispensing medicines or providing only advice, respectively. There were significant associations between the recommendation to dispense medicines for treatment of diarrhoea or constipation in breast feeding women and the respondents’ experience as practitioners (P<0.05). It was found to be more common among those with experience of >10 years compared with those with experience of <10 years (for diarrhoea: P=0.02; OR=2.0; 95% CI 1.1 to 3.5; for constipation: P=0.02; OR=2.2; 95% CI 1.1 to 4.2).

Figure 1.

Pharmacists’ responses to eight common symptoms in pregnancy and breast feeding (n=192).

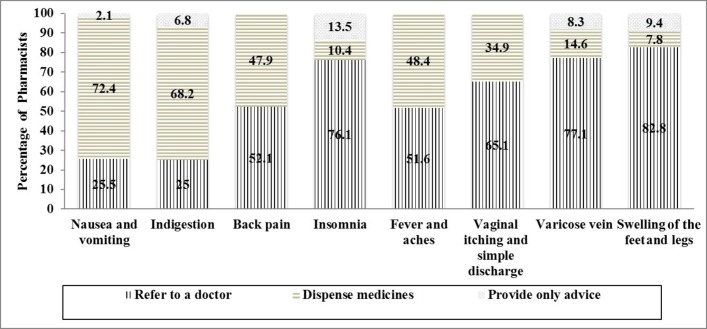

Figure 2 presents the distribution of pharmacists’ responses to the specific symptoms in pregnancy. Over half of respondents recommended referral of pregnant women to the doctor for swelling of the feet and legs, varicose vein, insomnia, vaginal itching, back pain, and fever and aches. More than two-thirds of participants recommended dispensing of medications for treatment of nausea, vomiting and indigestion. There was a significant association between the recommendation to dispense medicines for nausea/vomiting and the pharmacists’ experience as practitioners (P<0.05). It was found to be more common among those with experience of >10 years compared with those with experience of <10 years (P=0.03; OR=2.6; 95% CI 1.1 to 6.5). The recommendation to dispense medicines for treatment of vaginal itching was significantly more common among women compared with men (P=0.01; OR=2.3; 95% CI 1.2 to 4.4).

Figure 2.

Pharmacists’ responses to specific symptoms in pregnancy (n=192).

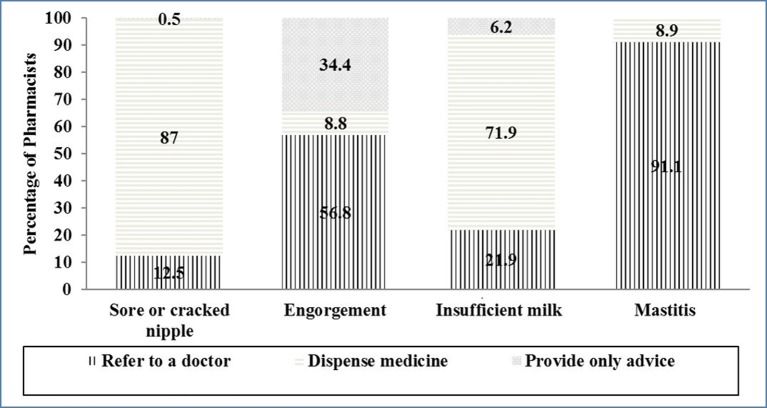

Figure 3 presents the distribution of pharmacists’ responses to the specific symptoms in breast feeding women. Pharmacists mainly recommended dispensing of medications for sore or cracked nipple and to increase the breast milk, and referral to the doctor for mastitis. There were significant associations between the recommendation to dispense medicine to relieve engorgement or increase the breast milk and gender. It was found to be more prevalent among women compared with men (for engorgement: P=0.01; OR=2.2; 95% CI 1.1 to 4.1; for insufficient milk: P=0.03; OR=2.5; 95% CI 1.1 to 5.9).

Figure 3.

Pharmacists’ responses to specific symptoms in breast feeding (n=192).

The medications that respondents recommended for each of the symptoms during pregnancy and breast feeding are presented in the supplementary file (online supplementary appendix 2). Most medicines that were recommended are not detrimental to the mother, fetus and infant. However, the respondents’ recommendations on medicine use were sometimes inappropriate in terms of unneeded drug therapy, off-label use and safety. Respondents sometimes recommended ibuprofen for headache, antibiotics for sore throat and productive cough, herbal products for cough, loratadine for runny nose and productive cough, stimulant laxatives for constipation, loperamide for diarrhoea, St John’s wort and melatonin for insomnia, topical products with no evidence to heal a nipple, paracetamol, moisturising cream and domperidone for engorgement, and herbal products that contain fenugreek for insufficient milk.

bmjopen-2017-018980supp002.pdf (290.6KB, pdf)

The Cronbach’s α test results for the sections to determine the pharmacists’ views about self-care in pregnancy and breast feeding were as follows: four statements of support self-care, 0.84; two statements about the safety of OTC medicines, 0.91; four statements about knowledge and confidence about pregnancy and breast feeding, 0.79; and two statements about undergraduate training in self-care for both pregnant and breast feeding women, 0.97. Table 2 shows the respondents’ views regarding self-care of pregnant and breast feeding women. In the first dimension about self-care support, more than half of respondents agreed that pharmacists are qualified to provide advice and an OTC therapy to treat symptoms in pregnant (58.9%) and breast feeding (65.1%) women. However, less than half of participants agreed that pharmacists should recommend an OTC therapy to treat symptoms in pregnant (39.1%) and breast feeding (46.9%) women. In the second dimension, more than two-fifths of participants disagreed about the safety of OTC medicines for pregnant (51.6%) and breast feeding (43.8%) women. In the third dimension about knowledge and confidence, more than half of pharmacists agreed that they are confident about providing advice and counselling to pregnant (58.3%) and breast feeding (53.1%) women; and that they have adequate knowledge to solve medication and health problems of pregnant (61.5%) and breast feeding (50.5%) women. In the last dimension about undergraduate training, 4 in 10 responders agreed that pharmacy schools provided appropriate training to provide advice and an OTC therapy for pregnant (44.3%) and breast feeding (42.2%) women. The agreement that OTC medicines are safe was significantly higher among women compared with men (P=0.04; OR=2.1; 95% CI 1.1 to 4.3).

Table 2.

Respondents views about self-care of pregnant and breast feeding women (n=192)

| Strongly disagree, (%) | Disagree, (%) | Neutral, (%) | Agree, (%) | Strongly agree, (%) | Median* (IQR) |

|

| Support self-care | ||||||

| Community pharmacists are qualified to provide advice and an over-the-counter (OTC) therapy to treat common and minor symptoms in pregnant women | 6 (3.1) | 29 (15.1) | 44 (22.9) | 84 (43.8) | 29 (15.1) | 4.0 (1.0) |

| Community pharmacists are qualified to provide advice and an OTC therapy to treat common and minor symptoms in breast feeding women | 4 (2.1) | 25 (13.0) | 38 (19.8) | 90 (46.9) | 35 (18.2) | 4.0 (1.0) |

| Community pharmacists should recommend OTC therapy and counselling to treat common and minor symptoms in pregnant women | 14 (7.3) | 49 (25.5) | 54 (28.1) | 55 (28.7) | 20 (10.4) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| Community pharmacists should recommend OTC therapy and counselling to treat common and minor symptoms in breast feeding women | 13 (6.8) | 40 (20.8) | 49 (25.5) | 72 (37.5) | 18 (9.4) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| Overall scale | 4.0 (1.0) | |||||

| Safety of OTC medicine | ||||||

| OTC medicines are safe for pregnancy | 29 (15.1) | 70 (36.5) | 52 (27.1) | 34 (17.7) | 7 (3.6) | 2.0 (1.0) |

| OTC medicines are safe for breast feeding | 19 (9.9) | 65 (33.9) | 56 (29.1) | 44 (22.9) | 8 (4.2) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| Overall scale | 3.0 (1.0) | |||||

| Knowledge and confidence about pregnancy and breast feeding | ||||||

| I am confident about giving advice and counselling to pregnant women | 8 (4.2) | 27 (14.1) | 45 (23.4) | 97 (50.5) | 15 (7.8) | 4.0 (1.0) |

| I have sufficient knowledge to solve medication and health problems of pregnant women | 7 (3.6) | 19 (9.9) | 48 (25.0) | 95 (49.5) | 23 (12.0) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| I am confident about giving advice and counselling to breast feeding women | 11 (5.8) | 25 (13.0) | 54 (28.1) | 83 (43.2) | 19 (9.9) | 4.0 (1.0) |

| I have sufficient knowledge to solve medication and health problems of breast feeding women | 14 (7.2) | 36 (18.8) | 45 (23.4) | 75 (39.1) | 22 (11.5) | 4.0 (1.0) |

| Overall scale | 4.0 (1.0) | |||||

| Undergraduate training | ||||||

| Pharmacy school provided appropriate training regarding advice and OTC therapy for pregnant women | 15 (7.8) | 40 (20.8) | 52 (27.1) | 70 (36.5) | 15 (7.8) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| Pharmacy school provided appropriate training regarding advice and OTC therapy for breast feeding women | 16 (8.4) | 40 (20.8) | 55 (28.6) | 65 (33.9) | 16 (8.3) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| Overall scale | 3.0 (2.0) | |||||

1= Strongly disagree; 2= Disagree; 3=Neutral; 4=Agree; 5=Strongly agree.

Most of the respondents (n=170; 88.5%; 95% CI 83.0% to 92.5%) agreed that a continuing education programme regarding this topic would be of value and priority for their practice. Attending lectures/workshops/seminars (n=80; 47.1%) was the most convenient method of delivering continuing education for them, followed by receiving regular newsletters (n=61; 35.9%), and receiving distant learning packages (n=34; 20%). There was no significant association between the respondents’ need for continuing education and the independent variables (age: P=0.44; gender: P=0.47; experience: P=0.49). The most commonly indicated sources of information used by respondents to prepare themselves for responding to symptoms in pregnancy and breast feeding was the websites (n=133; 69.2%), followed by books (n=99; 51.5%) and journal articles (n=19; 9.9%).

Discussion

The present results showed that community pharmacists in Kuwait are frequently consulted by pregnant and breast feeding women. Most of the pharmacists recommended medicines or referral to a doctor rather than providing advice only for the treatment of pregnancy-related and breast feeding-related ailments. Recommendations on medicati on use were occasionally inappropriate in terms of unneeded drug therapy, off-label use and safety. Some community pharmacists still lack confidence and knowledge to provide advice and resolve health and medication problems of pregnant and lactating women. To our knowledge, this is the first study to be performed in Kuwait, and the second in the Middle Eastern area, and it contributes to the limited amount of existing literature in the developing countries about the services provided by community pharmacists for women during pregnancy and lactation. The present results present a baseline quantitative data of these services that will aid in the assessment of the current pharmacy practices towards self-care during pregnancy and lactation, and offer additional insight in designing future multifaceted interventions to improve the community pharmacists’ role to deliver the proper advice and resolve the healthcare matters of pregnant and lactating women in Kuwait.

The current results reveal that the services most regularly offered to pregnant and lactating women were recommending vitamin or food supplements, referral to a doctor, contraception advice and weight control advice. These results are close to those indicated in the Thai study, with the exception that symptom diagnosis and medicine dispensing was a commonly provided service in Thailand.16 The study participants indicated that pregnant and lactating women most frequently consulted them regarding gastrointestinal symptoms, respiratory symptoms and safety of medicine use. It was reported that most people considered these gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms as minor ailments that can be treated by using OTC medicines that they tend to purchase from a community pharmacy.16 22 The finding that respondents were also frequently consulted about the safety of medicines use in pregnancy and lactation is in accordance with a previous report, which has shown that women require information regarding medication use during pregnancy and indicated pharmacists among the three mainly used sources of information.23 These findings indicate that women with pregnancy-related and lactation-related ailments were more tending to visit a pharmacist than a physician. This could be partly explained by the easy access to the community pharmacies, as it is evident that community pharmacies are recognised as the utmost reachable healthcare settings due to the high volume of the public who use their services.24 Furthermore, it may be due to the observation of the pharmacists by the pregnant and breast feeding women as the self-care consultant who provide them with enough time to discuss their health problems and prefer to get advice from a pharmacist rather than from a physician when they have non-serious condition.25–29 These findings indicate the relevance of maternal–fetal medication as a crucial area for pharmacy practice, which needs the pharmacists to have adequate knowledge and a responsible framework in paying particular attention when these women request advice to improve maternal health.

Respondents were also asked about the services that they would recommend for pregnancy-related and lactation-related ailments. More than half of pharmacists indicated that they would recommend medications for headache, constipation, cough, runny nose and sore throat as well as nausea/vomiting, indigestion, sore or cracked nipple and insufficient milk. In comparison to previous reports, a study conducted in France revealed that medications were often recommended by pharmacists for pain, fever, nose and oropharynx disorders, venous insufficiency, dyspepsia and constipation.14 In Thailand, about 75% of pharmacists treated headache, runny nose and sore throat with medicines. A recent study reported that 52% of pharmacists in Serbia recommended medication use for treatment of back pain, heavy legs, nausea, common cold and constipation during pregnancy, while 62% of respondents in Norway recommended non-pharmacological advice as well as referral to a doctor.17 These findings illustrate the large differences in community pharmacists’ practices between countries regarding the services recommended for treatment of pregnancy-related and lactation-related ailments. This could be partly explained by the differences in regulatory environments, types of undergraduate programme and the availability of products at the local pharmacies. The finding that less than one-tenth of the participants recommended only advice for most of the symptoms underscores the need for pharmacists to have sufficient knowledge and information about self-care practices which are crucial to alleviate some ailments without medications. The pharmacist must have adequate information to reach a conclusion about the risk:benefit ratio of treatment for the women to be able to counsel them effectively.

In the present study, recommendations on medication use were occasionally inappropriate in terms of unneeded drug therapy, off-label use and safety. Previous studies showed that community pharmacists were incapable to offer adequate evidence-based information about use of medicines during pregnancy.13 15 These results demonstrate that respondents have different knowledge levels in the subject of maternal–fetal medicine and underscore the need for continuing professional development and the revision of the undergraduate pharmacy curriculum to fill the knowledge gaps of pharmacy students and practitioners in maternal–fetal medicine and to support pharmacists to deliver the proper care for pregnant and lactating women.

The current findings reveal that pharmacists with experience of more than 10 years recommended to dispense medicines for diarrhoea, constipation and nausea/vomiting more than those with less experience. This might be due to that their knowledge base in the area of pregnancy-related and breast feeding-related ailments relies on experience gained in practice. Also, it was found that female respondents recommended to dispense medications for vaginal itching/simple discharge, engorgement and insufficient milk more than males. This could be explained by the fact that female pharmacists have more exposure to pregnancy-related issues, either personal or work experience. Furthermore, pregnant or lactating women tend to discuss their concerns more comfortable with female than male pharmacists. Another possible reason demonstrated by this study was their agreement that OTC medicines are safe, which was significantly higher than men. Further qualitative research is needed for describing and understanding these predictors.

Conclusions

The present results reveal that community pharmacists in Kuwait are frequently consulted by pregnant and breast feeding women and that the pharmacists had different approaches towards responding to pregnancy-related and lactation-related ailments. They also highlight the need for multifaceted interventions, including continuing professional development and the revision of the undergraduate pharmacy curriculum, to fill the knowledge gaps of pharmacy students and practitioners in maternal–fetal medicine and to enhance pharmacists’ role in improving maternal health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the participation of the community pharmacists in this study. We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of pharmacist Moodi Al-Asfour in pretesting the study questionnaire and data collection.

Footnotes

Contributors: AAI contributed in data collection, analysis and interpretation, and wrote the manuscript. AA designed and supervised the study, performed the data analysis and reviewed the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval (number 1593) was received from the ‘Ministry of Health Ethical Committee, Kuwait’ on 2 December 2014.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The raw data of the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. World self-medication industry (WSMI). WSMI declaration on self-care and self-medication. 2006. http://www.wsmi.org/wsmi-declaration-on-self-care-and-self-medication-2/ (accessed 7 Feb 2017).

- 2.Geissler PW, Nokes K, Prince RJ, et al. Children and medicines: self-treatment of common illnesses among Luo schoolchildren in western Kenya. Soc Sci Med 2000;50:1771–83. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00428-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buitendijk S, Bracken MB. Medication in early pregnancy: prevalence of use and relationship to maternal characteristics. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991;165:33–40. 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90218-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aviv RI, Chubb K, Lindow SW. The prevalence of maternal medication ingestion in the antenatal period. S Afr Med J 1993;83:657–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abeje G, Admasie C, Wasie B. Factors associated with self medication practice among pregnant mothers attending antenatal care at governmental health centers in Bahir Dar city administration, Northwest Ethiopia, a cross sectional study. Pan Afr Med J 2015;20:276 10.11604/pamj.2015.20.276.4243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yusuff KB, Omarusehe LD. Determinants of self medication practices among pregnant women in Ibadan, Nigeria. Int J Clin Pharm 2011;33:868–75. 10.1007/s11096-011-9556-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kulkarni PK, Khan M, Chandrasekhar A. Self-medication practices among Urban Slum dwellers in the south Indian city. Int J Pharma Bio Sci 2012;3:81–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Westfall RE. Herbal healing in pregnancy: women’s experiences. J Herb Pharmacother 2003;3:17–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaves RG, Lamounier JA, César CC. Self-medication in nursing mothers and its influence on the duration of breastfeeding. J Pediatr 2009;85:129–34. 10.2223/JPED.1874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Sawalha NA, Tahaineh L, Sawalha A, et al. Medication use in breast feeding women: a national study. Breastfeed Med 2016;11:386–91. 10.1089/bfm.2016.0044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lagoy CT, Joshi N, Cragan JD, et al. Medication use during pregnancy and lactation: an urgent call for public health action. J Womens Health 2005;14:104–9. 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP). International Pharmaceutical Federation report on effective use of pharmacists in improving maternal, newborn and child health. 2011. http://www.who.int/pmnch/media/news/2012/20120223_fip_paper/en/ (accessed 11 Feb 2017).

- 13.Schrempp S, Ryan-Haddad A, Galt KA. Pharmacist counseling of pregnant or lactating women. J Am Pharm Assoc 2001;41:887–90. 10.1016/S1086-5802(16)31330-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Damase-Michel C, Vié C, Lacroix I, et al. Drug counselling in pregnancy: an opinion survey of French community pharmacists. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2004;13:711–5. 10.1002/pds.954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyszkiewicz DA, Gerichhausen S, Björnsdóttir I, et al. Evidence based information on drug use during pregnancy: a survey of community pharmacists in three countries. Pharm World Sci 2001;23:76–81. 10.1023/A:1011227718654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sathon B. Self-care in pregnancy and breastfeeding: views of women and community pharmacists in Thailand. Dissertation Nottingham: University of Nottingham, 2010. http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/11605/ (accessed 26 Dec 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Odalović M, Milanković S, Holst L, et al. Pharmacists counselling of pregnant women: Web-based, comparative study between Serbia and Norway. Midwifery 2016;40:79–86. 10.1016/j.midw.2016.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bains S, Kitutu FE, Rahhal A, et al. Comparison of pharmacist knowledge, perceptions and training opportunities regarding maternal-fetal medicine in Canada, Qatar and Uganda. Can Pharm J 2014;147:345–51. 10.1177/1715163514552558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. State of kuwait: General Statistics Bureau. Statistical Review. 39 edn, 2011. https://www.csb.gov.kw/Socan_Statistic.aspx?ID=6 (accessed 02 Mar 2017).

- 20.Dupont WD, Plummer WD. Power and sample size calculations. version 3.1.2. 2014. http://biostat.mc.vanderbilt.edu/wiki/Main/PowerSampleSize (accessed 12 Jan 2015).

- 21. World Health Organization. 1993. How to investigate drug use in health facilities: Selected drug use indicators: Report WHO/DAP/: 92. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boardman H, Lewis M, Croft P, et al. Use of community pharmacies: a population-based survey. J Public Health 2005;27:254–62. 10.1093/pubmed/fdi032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hämeen-Anttila K, Jyrkkä J, Enlund H, et al. Medicines information needs during pregnancy: a multinational comparison. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002594 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson JK, Sweidan M, Spinks JM, et al. Public Health-Recognising the Role of Australian Pharmacists. J Pharm Pract Res 2004;34:290–2. 10.1002/jppr2004344290 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen J, Britten N. ‘Strong medicine’: an analysis of pharmacist consultations in primary care. Fam Pract 2000;17:480–3. 10.1093/fampra/17.6.480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bawazir SA. Consumer attitudes towards community pharmacy services in Saudi Arabia. Int J Pharm Pract 2004;12:83–9. 10.1211/0022357023718 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wazaify M, Al-Bsoul-Younes A, Abu-Gharbieh E, et al. Societal perspectives on the role of community pharmacists and over-the-counter drugs in Jordan. Pharm World Sci 2008;30:884–91. 10.1007/s11096-008-9244-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simoens S, Lobeau M, Verbeke K, et al. Patient experiences of over-the-counter medicine purchases in Flemish community pharmacies. Pharm World Sci 2009;31:450–7. 10.1007/s11096-009-9293-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilbur K, Salam SE, Mohammadi E. Patient perceptions of pharmacist roles in guiding self-medication of over-the-counter therapy in Qatar. Patient Prefer Adherence 2010;4:87–93. 10.2147/PPA.S9530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-018980supp001.pdf (308.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-018980supp002.pdf (290.6KB, pdf)