Abstract

Objectives

To (1) compare timely but preliminary and definitive but delayed radiological reports in a large urban level 1 trauma centre, (2) assess the clinical significance of their differences and (3) identify clinical predictors of such differences.

Design, setting and participants

We performed a retrospective record review for all 2914 patients who presented to our university affiliated emergency department (ED) during a 6-week period. In those that underwent radiological imaging, we compared the patients’ discharge letter from the ED to the definitive radiological report. All identified discrepancies were assessed regarding their clinical significance by trained raters, independent and in duplicate. A binary logistic regression was performed to calculate the likelihood of discrepancies based on readily available clinical data.

Results

1522 patients had radiographic examinations performed. Rater agreement on the clinical significance of identified discrepancies was substantial (kappa=0.86). We found an overall discrepancy rate of 20.35% of which about one-third (7.48% overall) are clinically relevant. A logistic regression identified patients’ age, the imaging modality and the anatomic region under investigation to be predictive of future discrepancies.

Conclusions

Discrepancies between radiological diagnoses in the ED are frequent and readily available clinical factors predict their likelihood. Emergency physicians should reconsider their discharge diagnosis especially in older patients undergoing CT scans of more than one anatomic region.

Keywords: diagnostic error, quality in health care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Retrospective record review of a real-world patient sample.

Clinically valid comparison between immediate first and delayed final radiological diagnosis.

Single-centre study, situated in a large urban emergency room, where many diagnoses are first made.

Designed to identify readily available predictors of misdiagnosis such as age, imaging modality and anatomic region.

Unable to determine long-term consequences due to retrospective design.

Introduction

Annually, between 100 000 and 250 000 patients in the USA alone die from medical errors.1 2 Diagnostic errors are a frequent and the most consequential medical error,2–6 and misdiagnosis thus is one of the greatest concerns for patients in the emergency department (ED).7 It furthermore has important economic and legal consequences.8 Errors in the assessment of radiographs are a potential source of such diagnostic errors. Especially in the ED, diagnostic errors might lead to iatrogenic harm to the patient.9

In most EDs, plain film radiographs (X-ray) are initially interpreted by the treating emergency physician (EP), and a definitive diagnosis by a radiologist is provided hours to days later. More complex examinations, including CT scans or MRI, are often interpreted immediately by a (junior) radiologist on duty and findings communicated to the EP,10 while a senior’s definitive approval of such reports might follow much later. Often, EPs additionally informally consult radiologists on duty on findings the EPs are uncertain about. Thus, two interpretations of radiographs typically exist in most EDs: an immediately available reading by EPs and potentially junior radiologists and a delayed but more reliable reading by senior radiologists. Treatment and discharge decisions in the ED are typically based on the former due to the time constraints in most EDs.

Previous studies have shown overall discrepancy rates in the interpretation of radiographic images between radiologists and EPs to range between 1.1%11 and 9.2%,12 although much higher discrepancy rates have been reported for specific types of examinations.13 However, missed radiological findings that would have resulted in an immediate change in the management of a patient have been reported to be exceedingly rare.14

Whereas differences in the interpretation of radiographic images between radiologists and EPs have been extensively researched, the discrepancies between preliminary results reported in the EDs discharge letter and the definitive radiology report are less well examined. We thus aimed to compare the preliminary findings reported by the ED with the definitive radiological reports and determine the clinical significance of any differences in order to estimate the resulting degree of consequential diagnostic errors. We further aimed to model the binary outcome discrepancy/no discrepancy based on clinical data readily available to the EP before discharge to provide the EP with an a priori estimate of the probability of error.

Patients and methods

This study is a retrospective review of all radiological studies ordered between December 2012 and January 2013 in a large urban academic ED and level 1 trauma centre that saw approximately 38 000 patients in 2013. The ED is staffed by physicians certified in internal medicine, surgery, traumatology and emergency medicine.15 We retrieved records of all adult patients presenting with traumatic or non-traumatic injury, medical or neurological chief complaints during the study period. Of these patients, we included all those for whom radiological studies had been ordered. Patients consulting directly with specialist clinics (orthopaedics, neurosurgery, hand surgery, plastic surgery, nephrology and urology) for non-urgent reasons were excluded since the procedures of how and when radiological findings are reported to the requesting physicians differ strongly depending on requesting departments. All relevant data, including age, gender, time of day, diagnosis and clinical management as noted in the discharge documents were retrieved from the ED patient management system (ECare ED V.2.1.3.0; E.care bvba, Turnhout, Belgium) and entered into a database (Microsoft Excel 14.0; Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, USA). Definitive radiological reports were retrieved from our digital radiological database (Spectra Workstation IDS 7; Sectra AB, Linköping, Sweden) and imaging modality categorised as either X-ray, CT, MRI, ultrasound (US) or scintigraphy (SCI). We further coded the body part examined as either head (including face and neck), chest, abdomen, skeletal system or other. The total number of imaging studies in each category was recorded.

We subsequently analysed the preliminary radiological report as given in the ED-discharge documents and compared them with the definitive radiological report, which was defined as the gold standard. Two independent reviewers analysed the data set and noted discrepancies between preliminary and definitive findings. Discrepancies were subsequently categorised by two independent EPs in duplicate as either ‘clinically significant’, that is, changing clinical management or ‘clinically insignificant’. Rater agreement was calculated as Cohen’s kappa and disagreements resolved by discussion. More than one abnormal finding may be present in any radiographic imaging, especially in patients with eg known comorbidities or after major trauma. Whenever rater encountered a discrepancy between the first and final radiological report, we counted this as a discrepancy. However, each image with a discrepancy was counted only once, regardless of the total number of discrepancies present on that image, leading to a conservative estimate of the total number of discrepancies. For each discrepancy identified per image, the clinical relevance was assessed separately but again counted only once if present.

Statistical analysis was conducted in SPSS V.22 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) and included descriptive statistics (frequency, mean and SD) and a logistic regression model. With the regression, we aimed to predict the binary outcome discrepancy versus no discrepancy between the radiological studies based on the patient’s age, gender, the imaging modality, the anatomic location of the radiological study and the time of day. Metric predictor variables (age and time of day) were z-standardised prior to the analysis to ensure comparability within the model. We refined the model stepwise by removing all non-significant predictor variables and report Nagelkerke’s R2 as measure of the models fit together with P values from Wald statistics and the respective regression coefficients. P values <0.05 were considered significant. We planned to assume data to be missing at random and thus impute missing data by means of a maximum likelihood estimation. We did however not encounter any missing data in the variables assessed in this study, which may result from the fact that we only retrieved very basic patient data such as gender or age.

Results

In the 6-week study period from 1 December 2012 to 15 January 2013, a total of 2914 patient visits were recorded in the ED. Of these, a total of 1522 patients, which corresponds to just over half (52.0%) of all patients, had at least one radiological study taken and were thus included in the study. On presentation, 608 of these patients had been triaged as surgical, 544 patients as medical and 360 patients as neurological emergencies. A majority of patients were men (n=868, 57.0%), and the median age was 53.74 years (minimum 16, maximum 98, SD 20.9). The majority of studies were ordered during daytime between 07:00 hours and 20:00 hours (n=1086) (table 1).

Table 1.

Total number of patients, overall and clinically significant discrepancies

| Variable | Total number of patients, n | Overall discrepancies, n (%) | Clinically significant discrepancies, n (%) | P value (significant discrepancies) |

| Specialty | ||||

| Surgery | 608 | 146 (24.0) | 39 (6.4) | 0.031 |

| Medicine | 504 | 130 (23.9) | 36 (6.6) | |

| Neurology | 360 | 57 (16.1) | 10 (2.8) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Women | 654 | 135 (20.6) | 36 (5.5) | 0.911 |

| Men | 868 | 230 (23.4) | 50 (5.8) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 65 and older | 543 | 176 (32.4) | 45 (8.3) | 0.002 |

| Under 65 | 979 | 162 (16.6) | 41 (4.2) | |

| Time of presentation | ||||

| Daytime | 1086 | 238 (21.9) | 51 (5.6) | 0.903 |

| Night-time | 436 | 100 (22.9) | 25 (5.7) | |

A total of 1875 radiological studies were performed, including 776 X-ray, 680 CT, 367 MRI, 49 US and 3 SCI. Due to their small number, SCIs were excluded from further analysis. The most common radiological studies ordered were CT of the head and neck (n=343), X-ray of the chest (n=319) and MRI of the head (n=329).

Rater agreement on whether or not discrepancies between discharge report and final radiological report were clinically significant was substantial (kappa=0.86). Overall, 381 discrepancies (20.35%) were found, of which 149 (7.48%) were judged to be clinically significant (table 2).

Table 2.

Number of radiological studies, overall and clinically significant discrepancies classified according to type of radiological study

| Radiological study | Overall | Overall discrepancies, n (%) |

Clinically significant discrepancies, n (%) |

| X-ray hand/wrist | 87 | 12 (13.79) | 2 (2.3) |

| X-ray thorax | 319 | 74 (23.2) | 22 (6.9) |

| X-ray spine | 48 | 11 (22.92) | 4 (8.34) |

| X-ray pelvis | 51 | 14 (27.45) | 4 (7.84) |

| X-ray knee | 56 | 4 (7.14) | 1 (1.79) |

| X-ray ankle/foot | 62 | 10 (16.13) | 5 (8.06) |

| X-ray other* | 153 | 14 (9.15) | 6 (3.92) |

| Sum X-ray | 776 | 139 (17.91) | 44 (5.67) |

| CT head/neck | 343 | 63 (18.37) | 29 (8.46) |

| CT thorax | 115 | 39 (33.91) | 17 (14.78) |

| CT abdomen | 114 | 31 (27.19) | 9 (7.9) |

| CT whole body | 57 | 27 (47.39) | 14 (24.56) |

| CT other† | 51 | 12 (23.53) | 5 (9.8) |

| Sum CT | 680 | 172 (25.29) | 74 (10.88) |

| MRI head | 329 | 55 (16.72) | 12 (3.65) |

| MRI spine | 32 | 7 (21.88) | 6 (18.75) |

| MRI other‡ | 6 | 4 (66.67) | 3 (50) |

| Sum MRI | 367 | 66 (17.98) | 21 (5.77) |

| Sum US | 49 | 4 (8.16) | 1 (2.04) |

| Sum total | 1872 | 381 (20.35) | 140 (7.48) |

*X-ray skull/Orthopantomagraphy (OPT) and body parts not otherwise specified.

†CTs of soft tissue and bone and from body parts not otherwise specified.

‡Body parts not otherwise specified.

US, ultrasound.

An example for a discrepancy judged as not clinically relevant is the CT scan of the head of patient 27, who was found unconscious. The radiographic report of the ED documents ‘no pathologies in contrast enhanced CT scan of the head’, while the final report points to ‘no explanation for acute unconsciousness identifiable, signs of chronic sinusitis’. The patient was found to be intoxicated with mixed substances. A relevant discrepancy, for example, was identified in patient 51, who presented with an acute abdomen due to a perforated sigmoid diverticulitis. While the ER’s report mentions this diagnosis of the CT of the abdomen, it fails to mention the infiltrate in the lower sections of the left lung, which the final report identified.

Whether or not a discrepancy between an initial radiological assessment and the definitive report by the department of radiology did or did not occur was predicted by several clinical variables. Logistic regression identified patients’ age, modality of imaging and anatomic region of the radiological study to be significant predictors (all P values <0.05), while time of day and patient gender had no significant predictive value. The model fits the data fairly well (R2=0.112) and would correctly predict outcome on 77.8% of the cases. Details of the model are given in table 3.

Table 3.

Results of the refined logistic regression model to predict a discrepancy between emergency department’s discharge report and definitive radiological report based on clinical characteristics

| Predictor | Regression coefficient | P value |

| Age | 0.472 | <0.001 |

| Imaging modality | −0.649 | 0.006 |

| Anatomic region | −1.085 | <0.001 |

| Constant | −0.584 | <0.001 |

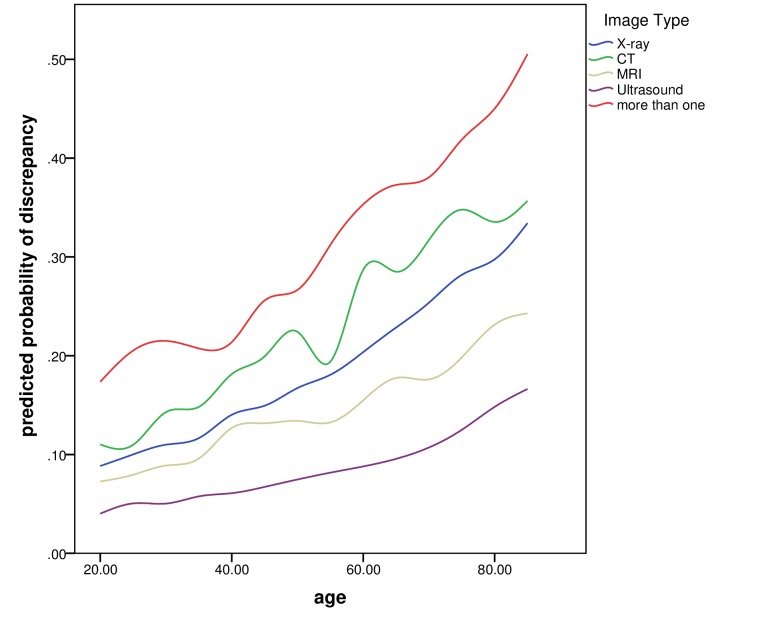

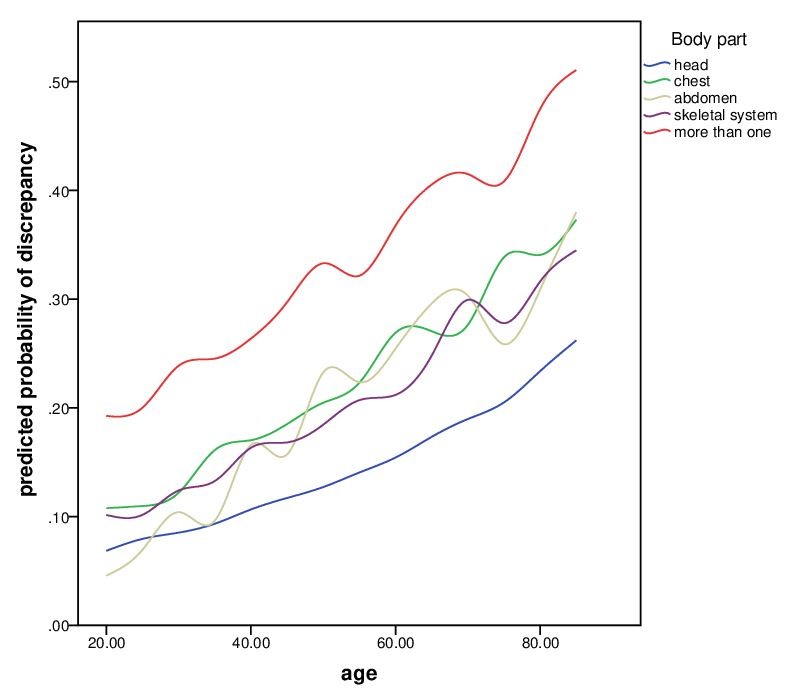

Figures 1 and 2 show the change in probability of a discrepancy predicted by the regression model based on age, imaging modality and anatomic region of the study.

Figure 1.

Probability of a discrepancy between first and final radiological diagnosis depending on body part over patient’s age.

Figure 2.

Probability of a discrepancy between first and final radiological diagnosis depending on image modality over patient’s age.

Discussion

Radiological images are an important part of medical diagnosis. In many EDs, patients’ radiographs are initially assessed by ED physicians as well as junior radiologists and treatment is determined based on their joint interpretation. A more definitive interpretation by senior radiologists is typically only available with a considerable delay.

Comparing the interpretation of radiographs in the discharge letter of ED patients to the final report from radiology, we found an overall discrepancy rate of 20.35%. Slightly more than one-third of these (7.48% overall) were deemed clinically relevant by two independent expert raters. The estimates of error from our study are well within the range of previous publications,11 12 14 16–18 which however mainly compared EPs’ reading of radiographs to senior radiologists. Such a comparison is only directly applicable to very small EDs as larger centres such as the one under investigation in our study typically have at least a junior radiologist on duty around the clock. Thus, the study reported here extends previous findings to the clinical reality in tertiary centres. A previous review of diagnostic error in medicine in general found the rate of critical discrepancies between a first and a second reading of images in visual specialties such as radiology, dermatology or pathology to range between 2% and 5%,19 just below the rate of discrepancies the raters deemed clinically relevant in our study.

Using a linear regression to model the likelihood of a discrepancy between first and final radiological diagnosis, we found several readily available clinical factors to be predictive of an error. These factors namely are patient age, imaging modality and region of the body under investigation. The factors are both plausible from a clinical perspective as well as in line with the sparse previous findings on the issue. Age has been previously found to be associated with diagnostic error20 and adverse events in the ED,21 likely because radiographs become harder to interpret in the presence of age-related or chronic findings.

We further found imaging modality and region of the body under investigation to be predictive of a discrepancy. From a clinical as well as a mathematical perspective, it is plausible that both more than one modality as well as more than one body region under investigation increase the likelihood of a discrepancy. Furthermore, two well-known cognitive sources of error are premature closure, that is, the failure to consider alternative diagnoses22 as well as satisfaction of search, that is, the termination of a diagnostic search after successful identification of one pathological finding.23 Both phenomena are less likely to occur with increasing expertise on a subject.24 Consequently, some authors have argued that the interpretation of any medical image should be exclusively left to experienced radiologists,25 while others argue that non-radiologists should simply be better trained,26 especially given the increasing availability of radiographic imaging.

One counterintuitive finding at first sight is the rather low discrepancy rates in MRIs of the head as well as in patients triaged as neurological emergencies. We assume these findings to be related because most MRIs of the head are ordered in patients with neurological chief complaints. One reason why the discrepancy rate in these patients is rather low may be the fact that neurologists are highly trained in interpreting cerebral MRI.27 Furthermore, the variety of possible interpretations is lower in cerebral MRIs than in a patient population with highly diverse body regions under investigation commonly triaged as medical or surgical chief complaints. Also, the likelihood of a coincidental finding in an MRI of the head, that is not related to the ER presentation and thus not actively searched for, is likely smaller than in, for example, a CT scan of the abdomen, where there simply is more to see and therefore a higher probability of an abnormality.

Our study has several limitations. First, this is a retrospective study susceptible to both documentation bias and hindsight bias.28 Prospective studies of diagnostic error are imperative and currently ongoing.29 Second, our study design does not allow us to discern whether the discrepancies identified between the final radiological report and the findings documented in the ED discharge report are due to misinterpretations by the junior radiologist, the discharging EPs or failed communication between the radiologist and the EP. However, regardless of where the error originates, it is the differences pragmatically assessed in this study that arguably matter most to the patient. Future studies focusing on collaboration in healthcare are needed30 because failed teamwork has been repeatedly identified as an important source of diagnostic error.6 Third, due to the retrospective nature of this study, we are unable to determine if and how the identified discrepancies were acted on. Future prospective investigations should include a follow-up on diagnostic discrepancies. Fourth, the study is a single-centre cohort study. Results may vary between centres and levels of care.

Last, one obvious question is why the estimates of error with and without consequence vary by an order of magnitude from author to author. We would offer two potential explanations. First, the definition of what constitutes a diagnostic error in general31 and a clinically significant difference in radiological diagnosis specifically is highly variable between publications, potentially resulting in different estimates. Second, due to time constraints, EPs may tend to only report findings they deem significant, which may explain the comparatively large number of insignificant differences found in our study.

In conclusion, we found a comparatively large number of discrepancies between radiological findings in patients discharge documentation compared with the final radiological report and identified age, imaging modality and body parts under investigation to be predictive of such discrepancies. All three predictors are readily available in clinical practice and should prompt EPs to reconsider their discharge diagnosis especially in older patients undergoing CT scans of more than one anatomic region.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sabina Utiger for her support in data management.

Footnotes

Contributors: Study design: BM, DE, AKE, LM, WEH. Data collection: BM, DE, LM. Expert raters: LM, AKE. Statistical analysis: WEH. Interpretation of results: BM, DE, AKE, LM, WEH. Drafting the manuscript: BM, DE, WEH. Substantial contribution to the manuscript for important intellectual content: BM, DE, AKE, LM, WEH.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: WEH received financial compensation for educational consultancies from the AO foundation, Zurich and speakers honorarium from Mundipharma Medical, Basel, Switzerland.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description/these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Ethics approval: Kantonale Ethikkomission Bern.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Original data are available from the corresponding author on request, provided the requesting person or party fulfills the data sharing requirements laid out by Kantonale Ethikkomission Bern.

References

- 1.Andel C, Davidow SL, Hollander M, et al. . The economics of health care quality and medical errors. J Health Care Finance 2012;39:39–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err Is Human. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz A, Elstein AS. Clinical reasoning in medicine : Clinical reasoning in the health professions. Edinburgh: Elsevier, 2008:223–34. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leape LL, Brennan TA, Laird N, et al. . The nature of adverse events in hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 1991;324:377–84. 10.1056/NEJM199102073240605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu TC, Tsai CL, Lee CC, et al. . Preventable deaths in patients admitted from emergency department. Emerg Med J 2006;23:452–5. 10.1136/emj.2004.022319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balogh EP, Miller BT, Ball JR : Balogh EP, Miller BT, Ball JR, Improving diagnosis in health care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burroughs TE, Waterman AD, Gallagher TH, et al. . Patient concerns about medical errors in emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med 2005;12:57–64. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2005.tb01480.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown TW, McCarthy ML, Kelen GD, et al. . An epidemiologic study of closed emergency department malpractice claims in a national database of physician malpractice insurers. Acad Emerg Med 2010;17:553–60. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00729.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawson CM, Daley BJ, Ormsby CB, et al. . Missed injuries in the era of the trauma scan. J Trauma 2011;70:452–8. discussion 456-458 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182028d71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunter TB, Krupinski EA, Hunt KR, et al. . Emergency department coverage by academic departments of radiology. Acad Radiol 2000;7:165–70. 10.1016/S1076-6332(00)80117-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warren JS, Lara K, Connor PD, et al. . Correlation of emergency department radiographs: results of a quality assurance review in an urban community hospital setting. J Am Board Fam Pract 1993;6:255–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fleisher G, Ludwig S, McSorley M. Interpretation of pediatric x-ray films by emergency department pediatricians. Ann Emerg Med 1983;12:153–8. 10.1016/S0196-0644(83)80557-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berner ES, Graber ML. Overconfidence as a cause of diagnostic error in medicine. Am J Med 2008;121(5 Suppl):S2–23. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petinaux B, Bhat R, Boniface K, et al. . Accuracy of radiographic readings in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med 2011;29:18–25. 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Exadaktylos A, Hautz WE. Emergency medicine in Switzerland. ICU Manag Pract 2015;15:160–2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gratton MC, Salomone JA, Watson WA. Clinically significant radiograph misinterpretations at an emergency medicine residency program. Ann Emerg Med 1990;19:497–502. 10.1016/S0196-0644(05)82175-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunswick JE, Ilkhanipour K, Seaberg DC, et al. . Radiographic interpretation in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med 1996;14:346–8. 10.1016/S0735-6757(96)90045-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nitowski LA, O’Connor RE, Reese CL. The rate of clinically significant plain radiograph misinterpretation by faculty in an emergency medicine residency program. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med 1996;3:782–9. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1996.tb03515.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graber ML. The incidence of diagnostic error in medicine. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22(Suppl 2):ii21–27. 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peng A, Rohacek M, Ackermann S, et al. . The proportion of correct diagnoses is low in emergency patients with nonspecific complaints presenting to the emergency department. Swiss Med Wkly 2015;145:9 10.4414/smw.2015.14121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aminzadeh F, Dalziel WB. Older adults in the emergency department: a systematic review of patterns of use, adverse outcomes, and effectiveness of interventions. Ann Emerg Med 2002;39:238–47. 10.1067/mem.2002.121523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eva KW. What every teacher needs to know about clinical reasoning. Med Educ 2005;39:98–106. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01972.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berbaum KS, Franken EA, Dorfman DD, et al. . Can order of report prevent satisfaction of search in abdominal contrast studies? Acad Radiol 2005;12:74–84. 10.1016/j.acra.2004.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ericsson KA, Charness N, Feltovich PJ, et al. . The Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance: Cambridge University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naeger DM, Webb EM, Zimmerman L, et al. . Strategies for incorporating radiology into early medical school curricula. J Am Coll Radiol 2014;11:74–9. 10.1016/j.jacr.2013.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zwaan L, Kok EM, van der Gijp A. Radiology education: a radiology curriculum for all medical students? Diagnosis 2017;4:185–9. 10.1515/dx-2017-0009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flanders AE, Flanders SJ, Friedman DP, et al. . Performance of neuroradiologic examinations by nonradiologists. Radiology 1996;198:825–30. 10.1148/radiology.198.3.8628878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zwaan L, Monteiro S, Sherbino J, et al. . Is bias in the eye of the beholder? A vignette study to assess recognition of cognitive biases in clinical case workups. BMJ Qual Saf 2017;26:104–10. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-005014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hautz SC, Schuler L, Kämmer JE, et al. . Factors predicting a change in diagnosis in patients hospitalised through the emergency room: a prospective observational study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011585 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hautz WE, Kämmer JE, Exadaktylos A, et al. . How thinking about groups is different from groupthink. Med Educ 2017;51:229 10.1111/medu.13137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zwaan L, Schiff GD, Singh H. Advancing the research agenda for diagnostic error reduction. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22(Suppl 2):ii52–57. 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.