Abstract

Background

The short-term outcomes and prognostic factors of patients with spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas (SDAVFs) have not been defined in large cohorts.

Objective

To define the short-term clinical outcomes and prognostic factors in patients with SDAVFs.

Methods

A prospective cohort of 112 patients with SDAVFs were included consecutively in this study. The patients were serially evaluated with the modified Aminoff and Logue’s Scale (mALS) one day before surgery and at 3 months, 6 months and 12 months after treatment. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to identify demographic, clinical and procedural factors related to favourable outcome.

Results

A total of 94 patients (mean age 53.5 years, 78 were men) met the criteria and are included in the final analyses. Duration of symptom ranged from 0.5 to 66 months (average time period of 12.7 months). The location of SDAVFs was as follows: 31.6% above T7 level, 48.4% between T7 and T12 level (including T7 and T12) and 20.0% below T12 level. A total of 81 patients (86.2%) underwent neurosurgical treatment, 10 patients (10.6%) underwent endovascular treatment, and 3 patients (3.2%) underwent neurosurgical treatment after unsuccessful embolisation. A total of 78 patients demonstrated an improvement in mALS score of one point or greater at 12 months. Preoperative mALS score was associated with clinical improvement after adjusting for age, gender, duration of symptoms, location of fistula and treatment modality using unconditional logistic regression analysis (p<0.05).

Conclusion

Approximately four fifths of the patients experienced clinical improvement at 12 months and preoperative mALS was the strongest predictor of clinical improvement in the cohort.

Keywords: embolisation, neurosurgical treatment, outcome, prognostic factors, spinal dural arteriovenous fistula

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The first prospective cohort study with a large sample size considering the incidence of spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas (SDAVFs). This study monitored a continuous change in spinal cord function post treatment.

The modified Aminoff and Logue’s Scale focuses on motor and sphincter status. Validated quality of sensory function evaluation would be imperative.

The study lacks imaging analysis

For the time being, the study has been a short-term follow-up, while our long-term follow-up is still ongoing.

Introduction

Spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas (SDAVFs) are rare with an incidence of only 5–10 new cases per million persons per year.1 Neurosurgery and endovascular treatment are both effective options.2 According to a meta-analysis, 89% of patients showed improvement or stabilisation of symptoms after treatment.3 However, due to the low incidence rate of SDAVFs, previous studies that have been published reporting on the clinical outcome and prognostic factors of SDAVFs are limited due to small sample size and/or unstandardised outcome assessment due to their retrospective nature. In these studies, the preoperative severity of disability was identified to be the most important prognostic factor.4–7 Previous studies have demonstrated conflicting results regarding the relationship between age, gender and duration of symptoms prior to treatment and treatment outcome.4–8 In addition, small sample sizes of previous studies mean that they are unable to adequately address the relationship between angioarchitecture and location of the lesion, despite the recognition that lesions located in craniocervical and sacrococcygeal regions are more complex.9–12 Previous studies and meta-analyses have consistently identified the lack of standardised long-term follow-up data as a major limitation to better understanding of the natural history of SDAVFs.

To address gaps in our understanding of SDAVFs, we conducted a prospective cohort study to evaluate the 1 year outcome of patients with cervical and thoracolumbar SDAVFs and identify the main prognostic factors.

Methods

Study design

We performed a prospective, longitudinal cohort study at two referral centres using the STROBE guideline.13 Both hospitals are the regional referral centres for SDAVFs and provide neurosurgical and endovascular treatments. This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committees at each site. Informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Participants and setting

We prospectively collected data on patients with SDAVFs located at the cervical and thoracolumbar regions, who underwent treatment at the two referral centres between March 2013 and December 2014 using a standard data collection form. All patients SDAVFs who were evaluated were considered for participation. Patients who had been previously treated with endovascular or surgical treatment, those with limb or sphincter dysfunction caused by other lesions, or those who refused treatment were excluded. The data were analysed by one of three designated investigators who did not participate in the treatment process. The treatment strategies (neurosurgery or endovascular) were decided by consensus after review by a team of experienced neurosurgeons and neuroradiologists.

Intervention

Spinal angiography was performed in all patients, including angiography of at least two segmental arteries above and below the target segmental artery bilaterally. Neurosurgical treatment was the preferred choice. All patients underwent hemilaminectomy in the location of the fistula followed by cauterisation. Indocyanine green angiography was used before and after coagulation to identify and confirm fistula obliteration between the arterial feeder and the draining vein. Endovascular treatment was considered for patients who were assessed as high risk of general anaesthesia, but did not have any arterial feeders from the radicular artery of Adamkiewicz. Embolisation was performed under local anaesthesia and a transfemoral approach was used. A Marathon 1.5-French microcatheter (ev3 Inc.) was used for selective catheterisation of the radiculomeningeal artery. Onyx (ev3 Inc.) was injected thorough the microcatheter as close as possible to the fistula until the proximal part of the draining vein was obliterated. However, if endovascular treatment was unsuccessful in achieving obliteration of SDAVFs, neurosurgical treatment was performed.

Data collection

Clinical data including age, gender, duration of symptoms, location of fistula, spinal functional status and treatment methods were collected. The onset of symptoms was considered to be when neurological deficits (gait disturbances, paresthesia, diffuse or patchy sensory loss, and bowel or bladder incontinence) were first noticed. We also recorded the time interval between symptom onset and treatment. The images of pre-procedure spinal angiogram were reviewed by one of two senior authors to identify the location of SDAVFs. The functional status of the patients was assessed using the modified Aminoff and Logue’s Scale (mALS, which grades gait, urinary incontinence and faecal continence/constipation, table 1) one day before the procedure, and at 3, 6 and 12 months post procedure.14 An effort was made to perform spinal angiography and MRI during the follow-up period when feasible.

Table 1.

Modified Aminoff and Logue’s Scale

| Gait (G) | |

| 0 | Normal leg power, stance and gait |

| 1 | Leg weakness with no restriction of walking |

| 2 | Restricted exercise tolerance |

| 3 | Requires one stick or some support for walking |

| 4 | Requires crutches or two sticks for walking |

| 5 | Requires a wheelchair |

| Urination (U) | |

| 0 | Normal |

| 1 | Urgency, frequency and/or hesitancy |

| 2 | Occasional incontinence or retention |

| 3 | Persistent incontinence or retention |

| Defecation (F) | |

| 0 | Normal |

| 1 | Mild constipation, responding well to apperients |

| 2 | Occasional incontinence or persistent constipation |

| 3 | Persistent incontinence |

Bias

Loss to follow-up might bias the results. Nine patients were lost to follow-up; the follow-up rate was 87.4% and those lost to follow-up and those followed-up at 12 months had similar baseline demographics and characteristics (online supplementary file). Therefore, recall bias might affect data entry, but this was minimised by ensuring that data were entered in a timely fashion.

bmjopen-2017-019800supp001.pdf (95.8KB, pdf)

Statistical analysis

Formal sample size calculations were not performed. All data were descriptively presented using mean ±SD for continuous data and frequencies for categorical data. Paired t tests (with adjustment for multiple comparisons) were used to assess differences in means for the cohort between baseline and different follow-up time points. Pearson χ2 tests were used to find factors associated with preoperative status. Pearson χ2 tests and unconditional logistic regression were used to identify factors affecting clinical improvement at 12 months. Clinical improvement was defined as a decrease of at least one point on the mALS compared with baseline assessment at 12 months. In the multivariate model, age (<=55 y or >55 y), gender (men/women), time interval between symptom onset and treatment (≤6 months, >6 months and ≤12 months or >12 months), location (above T7, T7–T12 or below T12), treatment performed (neurosurgical treatment, endovascular treatment or both), and preoperative mALS were entered. The preoperative mALS was classified as follows: a total score of 0–3 indicated a mild disability, a score of 4–7 a moderate disability and a score of 8–11 a severe disability. Clinical improvement was entered as the dichotomous dependent variable. Interactions were tested in the model. The OR and 95% CI were determined for significant variables in the model. All analyses were performed under the conduct of the epidemiologist using SPSS software (version 21, IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

Patient population

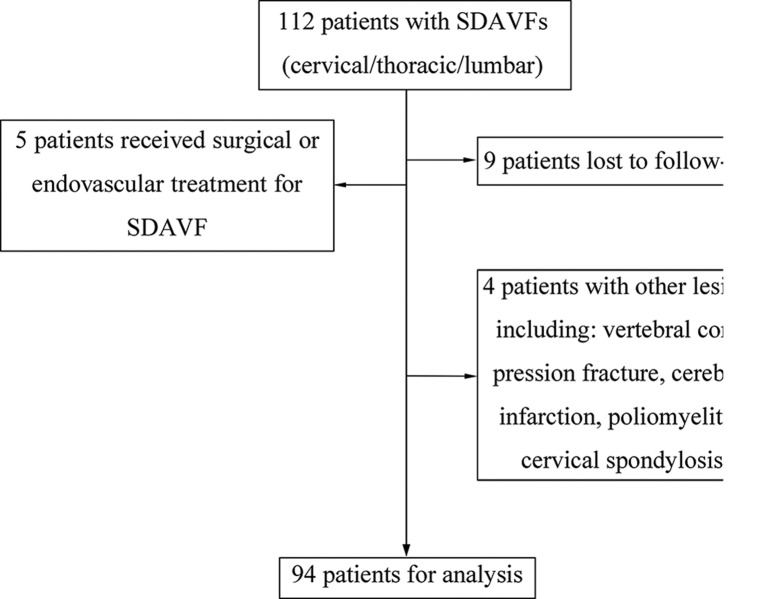

The baseline demographic characteristics of these 94 patients are presented in table 2. A total of 112 patients were screened for inclusion in the study; 18 patients were excluded (figure 1) due to previous history of treatment for the fistula (n=5, three underwent surgery and two underwent embolisation); with other lesions that induced neurological deficits (n=4); nine patients were lost to follow-up (two died due to unrelated events, lung cancer and intracranial haemorrhage, and seven were not accessible).

Table 2.

Baseline demographics and characteristics of patients with SDAVFs*

| Characteristics | Number (%) |

| Age at treatment, average (SD), years | 53.5 (10.7) |

| Men, n (%) | 78 (83.0) |

| Time interval between symptoms and treatment, average (SD), months | 12.7 (12.8) |

| ≤6 months, n (%) | 37 (39.4) |

| 6–12 m, n (%) | 28 (29.8) |

| >12 m, n (%) | 29 (30.8) |

| Location of the fistula, n (%) | |

| Above T7 | 30 (31.6%) |

| T7–T12 | 46 (48.4%) |

| Below T12 | 19 (20.0%) |

| Treatment method, n (%) | |

| Neurosurgery | 81 (86.2%) |

| Endovascular | 10 (10.6%) |

| Combination | 3 (3.2%) |

| Preoperative mALS, n (%) | |

| G score | |

| 0 | 5 (5.3%) |

| 1 | 9 (9.6%) |

| 2 | 39 (41.5%) |

| 3 | 18 (19.1%) |

| 4 | 8 (8.5%) |

| 5 | 15 (16.0%) |

| average (SD) | 2.6 (1.4) |

| U score | |

| 0 | 11 (11.7%) |

| 1 | 41 (43.6%) |

| 2 | 25 (26.6%) |

| 3 | 17 (18.1%) |

| average (SD) | 1.5 (0.9) |

| F score | |

| 0 | 8 (8.5%) |

| 1 | 57 (60.6%) |

| 2 | 24 (25.5%) |

| 3 | 5 (5.4%) |

| average (SD) | 1.3 (0.7) |

*patient with two fistulas (T8, T10).

F, faeces; G, gait; mALS, modified Aminoff and Logue’s Scale; SDAVF, spinal dural arteriovenous fistula; T, thoracic; U, urination.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram demonstrating inclusion and exclusion of screened patients. SDAVF, spinal dural arteriovenous fistula.

A total of 94 patients were included (mean age 53.5±10.7 years; 78 were men) with 95 SDAVFs. The mean time interval between symptom onset and procedure was 12.7 months (range 0.5–66 months). The most common location for SDAVFs was lower thoracic (T7–12, 48.4%). Before treatment, the patients presented with median mALS of 5 (range 0–11), the median G score was 2 (range 0–5), U score was 1 (range 0–3) and F score was 1 (range 0–3). A total of 81 patients (86.2%) underwent neurosurgical treatment, 10 patients (10.6%) underwent endovascular treatment, and three patients (3.2%) underwent neurosurgical treatment after unsuccessful endovascular treatment. In one patient, the fistula was obliterated after first embolisation, but required neurosurgery for recurrence demonstrated on 8-month follow-up angiography.

Clinical outcome

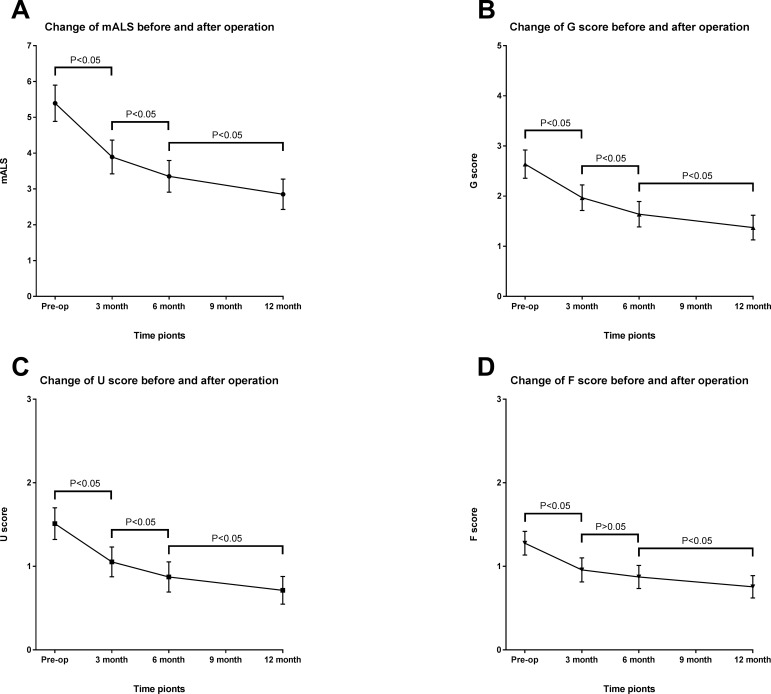

The pattern of change in mALS scores at 3, 6 and 12 months post treatment is presented in figure 2. There was improvement in mALS scores at all time points compared with baseline mALS scores. The highest improvement in mALS scores was seen between baseline and 3 months post treatment evaluation. However, the differences between the two adjacent follow-up time points were significant (p<0.05), except the change of F score between 3 months and 6 months (p=0.09). At 1 year follow-up, 78 patients (83.0%) experienced improvement of their mALS, 70 patients (74.5%) experienced improvement of the gait disability, 55 patients (58.5%) experienced improvement of the urination function and only 41 patients (43.6%) experienced improvement of defecation function. In addition, 10 of the 18 patients (55.6%) with mild disability showed improvement, in 43 of the 60 patients (71.7%) with moderate disability the level decreased to mild, in 4 of the 16 patients (25.0%) with severe disability the level decreased to mild, while in 9 patients (56.2%) the level decreased to moderate. For patients with a motor score of 5, only 40% were able to ambulate independently at 1 year.

Figure 2.

Change in modified Aminoff and Logue’s Scale (mALS) (A), gait (G) score (B), urine (U) score (C) and faeces (F) score (D) before and after surgery in patients with spinal dural arteriovenous fistula (SDAVFs) (mean and 95% CIs).

Prognostic factors

The preprocedural mALS was found to be related to the clinical improvement at 1 year. In the logistic regression model, a preprocedural mALS score of 4–7 (OR 8.98, 95% CI 2.1 to 38.4) and score of 8–11 (OR 20.8, 95% CI 1.6 to 269.2) were associated with higher rates of clinical improvement at 1 year. There was a trend towards an inverse relationship between age (when entered as a continuous variable) and higher rate of clinical improvement (OR 0.26, 95% CI 0.06 to 1.1). The duration of symptoms, location of fistula, and treatment method used were not related to the outcome (table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with clinical improvement at 1 year: univariate and multivariate analysis

| Variable | Patients with improvement, n (%) | Patients without improvement, n (%) | Univariate model | Multivariate model | ||

| χ2 | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |||

| Age | 0.734 | 0.392 | 0.264 (0.064 to 1.084) | 0.065 | ||

| ≤55 years | 48 (85.7%) | 8 (14.3%) | ||||

| >55 years | 30 (78.9%) | 8 (21.1%) | ||||

| Gender | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.963 (0.174 to 5.314) | 0.965 | ||

| Men | 65 (83.3%) | 13 (16.7%) | ||||

| Women | 13 (81.3%) | 3 (18.8%) | ||||

| Time interval between symptom onset and treatment | 2.064 | 0.356 | 0.374 | |||

| ≤6 months | 33 (89.2%) | 4 (10.8%) | Reference | |||

| 6–12 months | 23 (82.1%) | 5 (17.9%) | 0.520 (0.093 to 2.925) | 0.458 | ||

| >12 months | 22 (75.9%) | 7 (24.1%) | 0.327 (0.068 to 1.562) | 0.161 | ||

| Location of the fistula | 2.977 | 0.226 | 0.389 | |||

| Above T7 | 22 (73.3%) | 8 (26.7%) | Reference | |||

| T7–T12 | 39 (86.7%) | 6 (13.3%) | 2.396 (0.571 to 10.049) | 0.232 | ||

| Below T12 | 17 (89.5%) | 2 (10.5%) | 3.605 (0.377 to 37.427) | 0.265 | ||

| Treatment method | 0.918 | 0.632 | 0.303 | |||

| Neurosurgery | 67 (82.7%) | 14 (17.3%) | Reference | |||

| Endovascular | 9 (90.0%) | 1 (10.0%) | 0.626 (0.045 to 8.649) | 0.726 | ||

| Combination | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | 0.105 (0.006 to 1.831) | 0.122 | ||

| Preoperative mALS | 12.116 | 0.002 | 0.006 | |||

| 0–3 | 10 (55.6%) | 8 (44.4%) | Reference | |||

| 4–7 | 53 (88.3%) | 7 (11.7%) | 8.983 (2.104 to 38.357) | 0.003 | ||

| 8–11 | 15 (93.8%) | 1 (6.3%) | 20.792 (1.606 to 269.164) | 0.020 | ||

mALS, modified Aminoff and Logue’s Scale; T, thoracic.

Discussion

Our study provides the pattern of recovery and prognostic factors using a large patient cohort with SDAVFs using prospective standardised evaluation.

Outcome of patients with SDAVFs

In an analysis of a large cohort study of surgically treated patients with myelopathy from SDAVFs, continuous improvement after hospital discharge was confirmed, and the process lasted a long time. Approximately 97% of patients experienced improvement (82.2%) or stabilisation (14.4%) of their motor symptoms, while the sphincter dysfunction improved after surgery in 45% of patients.15 16 We obtained similar results in this study; at 1-year follow-up, the percentage of patients who experienced improvement in their motor symptoms was 74.5%, and stabilisation was 22.3%. Only 58.5% of patients experienced recovery of their urination function, and in terms of defecation function, the percentage was 43.6%. We also confirmed the recovery would continue for a long period after the operation, but improvements in the first 3 months were more obvious. This may suggest early rehabilitation exercises.

Prognostic factors

As we found in this study, age, sex, duration of symptom and location of fistula were not directly correlated to the postoperative outcome. Nagata et al suggested that outcome was better in younger patients6; however, in our cohort, younger age (≤55 years) did not correlate with improved clinical outcome at 1-year follow-up. Moreover, no correlation was found between duration of symptoms and short-term outcome; this was also found in various studies.4 6 8 17 Cenzato et al found that location of fistula could predict outcome; patients with a fistula between T9 and T12 improved more than those with a fistula elsewhere.5 8 In our results, most of the fistulas were located between T7 and T12; no association was found between clinical improvement and level of fistula. Besides, lower cervical SDAVFs are extremely rare.18 In our study, only one case located at the C5 level presented with congestive venous oedema at the thoracic cord. We also included a patient with double SDAVFs, which is also extremely rare.19 The two fistulas were separate; one was at T8 on the right and one at T10 on the left, the venous drainage was also separate.

Regardless of the therapeutic method of choice, the primary goal of SDAVF treatment must be the interruption of the fistula. A meta-analysis has been performed showing an advantage of primary surgical treatment of SDAVFs over endovascular treatment in terms of initial fistula closure and fistula recurrence. In 2004, Steinmetz et al reported a success rate of 46% in the endovascular group,3 while in 2015, Bakker et al found the proportion to be 72.2%.20 This may reflect the advancement in endovascular techniques that has been made over the last decade. In this study, there were a total of 13 patients undergoing embolisation: 10 patients had obliteration, two patients not cured with embolisation were treated with microsurgery, and one patient experienced delayed recurrence at 8-month angiography. So the success rate of endovascular treatment in our study was 76.9%. As presented previously, either microsurgery occlusion or endovascular embolisation did not show statistical significance with regards to outcome. Complications were considered; at 3-month follow-up, nine patients who underwent neurosurgery experienced worsening of their mALS, and one patient who we lost to follow-up experienced surgical site infection. Venous thrombosis might be considered to cause aggravation, while anticoagulation therapy cannot be administrated during the early postoperative period. Prophylactic anticoagulation was suggested for patients who experienced secondary clinical deterioration after successful embolisation.21 This is the advantage of endovascular treatment.

It seems to be widely recognised that preoperative functional status had an impact on clinical outcome,5 6 17 while one other study came to a different conclusion.3 Our results confirm that preoperative mALS was associated with functional outcome. Patients with more severe deficits before surgery were more likely to show improvement. Besides, in our cohort, we also found that age, gender, duration of symptoms and location of fistula were not correlated with preoperative mALS. It seems that longer duration may result in worse symptoms, but patients with SDAVFs could experience acute neurological deterioration,22 and also could be asymptomatic.23 Moreover, acute paraplegia could be induced by corticosteroid administration in misdiagnosed patients and could also be exacerbated by hydrostatic forces resulting from erect posture, abnormal compression, and the Valsalva manoeuvre.24 25 It is widely recognised that the pathophysiology of SDAVFs is chronic hypoxia and progressive myelopathy induced by venous hypertension.26 The acute aggravation showed that the change of blood flow in shunting cross the SDAVF or rapid infusion of saline solution could also be physiological factors affecting the disease course.27

SDAVFs are really rare diseases. Our prospective cohort recruited 94 consecutive patients; we hope to have presented generalisable results. The participants were from different provinces in China, and the inclusion criteria were set without age and gender limitations. Given the large series size and consecutive participants, we were able to reveal a result that was closer to the real situation.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, the investigator analyses the spinal function based on mALS which focuses only on motor and sphincter status. Validated quality of sensory function evaluation would be imperative. Second, the study lacks imaging analysis. The imaging features on MRI have been studied. Patients with enlarged draining veins (>10 spinal levels) had worse mALS scores, and more extensive draining veins were associated with more spinal cord T2 hyperintensity,28 and the extent of the hyperintensity area was relevant to preoperative neurological deficits.29 But the T2 signal abnormality of the spinal cord was not associated with clinical outcome.2 30 Finally, this is a short-term follow-up; long-term follow-up is ongoing.

Conclusion

This prospective cohort study shows that preoperative mALS is related to outcome in patients with SDAVFs. Most patients can recover after interruption of the fistula either by microsurgery or endovascular treatment, especially during the first 3 months during which the recovery is more obvious.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all the patients for cooperation. We also gratefully acknowledge Zhang Yiwen and Hugo Lam for help in polishing this article.

Footnotes

FL and HZ contributed equally.

Contributors: YM, study concept and design, acquisition of data. SC, investigator. CP, investigator. CW, analysis and interpretation of data. GL, operator. CH, operator. MY, operator. TH, operator. LB, site investigator. JL, site investigator. ZW, director of Coordinating Center (Beijing Haidian Hospital). Adnan I. Qureshi, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. FL, study supervision. HZ, study supervision.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Award Number: 81171165;81671202); Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (Award Number: D161100003816001).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committees at each site.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional unpublished data are available.

References

- 1.Thron A. Spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas. Radiologe 2001;41:955–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Song JK, Vinuela F, Gobin YP, et al. Surgical and endovascular treatment of spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas: long-term disability assessment and prognostic factors. J Neurosurg 2001;94:199–204. 10.3171/spi.2001.94.2.0199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinmetz MP, Chow MM, Krishnaney AA, et al. Outcome after the treatment of spinal dural arteriovenous fistulae: a contemporary single-institution series and meta-analysis. Neurosurgery 2004;55:77–88. 10.1227/01.NEU.0000126878.95006.0F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wakao N, Imagama S, Ito Z, et al. Clinical outcome of treatments for spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas: results of multivariate analysis and review of the literature. Spine 2012;37:482–8. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31822670df [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cenzato M, Debernardi A, Stefini R, et al. Spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas: outcome and prognostic factors. Neurosurg Focus 2012;32:E11 10.3171/2012.2.FOCUS1218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagata S, Morioka T, Natori Y, et al. Factors that affect the surgical outcomes of spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas. Surg Neurol 2006;65:563–8. 10.1016/j.surneu.2005.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tacconi L, Lopez Izquierdo BC, Symon L. Outcome and prognostic factors in the surgical treatment of spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas. A long-term study. Br J Neurosurg 1997;11:298–305. 10.1080/02688699746078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cenzato M, Versari P, Righi C, et al. Spinal dural arteriovenous fistulae: analysis of outcome in relation to pretreatment indicators. Neurosurgery 2004;55:815–23. 10.1227/01.NEU.0000137630.50959.A7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sato K, Endo T, Niizuma K, et al. Concurrent dural and perimedullary arteriovenous fistulas at the craniocervical junction: case series with special reference to angioarchitecture. J Neurosurg 2013;118:451–9. 10.3171/2012.10.JNS121028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeon JP, Cho YD, Kim CH, et al. Complex spinal arteriovenous fistula of the craniocervical junction with pial and dural shunts combined with contralateral dural arteriovenous fistula. Interv Neuroradiol 2015;21:733–7. 10.1177/1591019915609128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong T, Park JE, Ling F, et al. Comparison of 3 different types of spinal arteriovenous shunts below the conus in clinical presentation, radiologic findings, and outcomes. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2017;38:403–9. 10.3174/ajnr.A5001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang JY, Molenda J, Bydon A, et al. Natural history and treatment of craniocervical junction dural arteriovenous fistulas. J Clin Neurosci 2015;22:1701–7. 10.1016/j.jocn.2015.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007;370:1453–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aminoff MJ, Logue V. The prognosis of patients with spinal vascular malformations. Brain 1974;97:211–8. 10.1093/brain/97.1.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saladino A, Atkinson JL, Rabinstein AA, et al. Surgical treatment of spinal dural arteriovenous fistulae: a consecutive series of 154 patients. Neurosurgery 2010;67:1350–8. 10.1227/NEU.0b013e3181ef2821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muralidharan R, Mandrekar J, Lanzino G, et al. Prognostic value of clinical and radiological signs in the postoperative outcome of spinal dural arteriovenous fistula. Spine 2013;38:1188–93. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31828b2e10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cecchi PC, Musumeci A, Faccioli F, et al. Surgical treatment of spinal dural arterio-venous fistulae: long-term results and analysis of prognostic factors. Acta Neurochir 2008;150:563–70. 10.1007/s00701-008-1560-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aviv RI, Shad A, Tomlinson G, et al. Cervical dural arteriovenous fistulae manifesting as subarachnoid hemorrhage: report of two cases and literature review. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004;25:854–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krings T, Mull M, Reinges MH, et al. Double spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas: case report and review of the literature. Neuroradiology 2004;46:238–42. 10.1007/s00234-003-1147-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakker NA, Uyttenboogaart M, Luijckx GJ, et al. Recurrence rates after surgical or endovascular treatment of spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas: a meta-analysis. Neurosurgery 2015;77:137–44. 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knopman J, Zink W, Patsalides A, et al. Secondary clinical deterioration after successful embolization of a spinal dural arteriovenous fistula: a plea for prophylactic anticoagulation. Interv Neuroradiol 2010;16:199–203. 10.1177/159101991001600213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joswig H, Haji FA, Martinez-Perez R, et al. Rapid recovery from paraplegia in a patient with foix–alajouanine syndrome. World Neurosurg 2017;97:750.e1–750.e3. 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.10.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato K, Terbrugge KG, Krings T. Asymptomatic spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas: pathomechanical considerations. J Neurosurg Spine 2012;16:441–6. 10.3171/2012.2.SPINE11500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Keeffe DT, Mikhail MA, Lanzino G, et al. Corticosteroid-induced paraplegia—a diagnostic clue for spinal dural arterial venous fistula. JAMA Neurol 2015;72:833–4. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.0757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKeon A, Lindell EP, Atkinson JL, et al. Pearls & oy-sters: clues for spinal dural arteriovenous fistulae. Neurology 2011;76:e10–e12. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182074a42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hurst RW, Kenyon LC, Lavi E, et al. Spinal dural arteriovenous fistula: the pathology of venous hypertensive myelopathy. Neurology 1995;45:1309–13. 10.1212/WNL.45.7.1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cabrera M, Paradas C, Márquez C, et al. Acute paraparesis following intravenous steroid therapy in a case of dural spinal arteriovenous fistula. J Neurol 2008;255:1432–3. 10.1007/s00415-008-0943-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hetts SW, Moftakhar P, English JD, et al. Spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas and intrathecal venous drainage: correlation between digital subtraction angiography, magnetic resonance imaging, and clinical findings. J Neurosurg Spine 2012;16:433–40. 10.3171/2012.1.SPINE11643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horikoshi T, Hida K, Iwasaki Y, et al. Chronological changes in MRI findings of spinal dural arteriovenous fistula. Surg Neurol 2000;53:243–9. 10.1016/S0090-3019(99)00168-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fugate JE, Lanzino G, Rabinstein AA. Clinical presentation and prognostic factors of spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas: an overview. Neurosurg Focus 2012;32:E17 10.3171/2012.1.FOCUS11376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-019800supp001.pdf (95.8KB, pdf)